Wardowski conditions to the coincidence problem

- 1Departamento de Análisis Matemático, Universidad de Sevilla, Sevilla, Spain

- 2Departament d'Anàlisi Matemàtica, Universitat de València, València, Spain

- 3Departamento de Matemáticas, Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain

In this article we first discuss the existence and uniqueness of a solution for the coincidence problem: Find p ∈ X such that Tp = Sp, where X is a nonempty set, Y is a complete metric space, and T, S:X → Y are two mappings satisfying a Wardowski type condition of contractivity. Later on, we will state the convergence of the Picard-Juncgk iteration process to the above coincidence problem as well as a rate of convergence for this iteration scheme. Finally, we shall apply our results to study the existence and uniqueness of a solution as well as the convergence of the Picard-Juncgk iteration process toward the solution of a second order differential equation.

1. Introduction

Let X, Y be two nonempty sets and let T, S : X → Y be two arbitrary mappings. The coincidence problem determined by the mappings T and S consists in

Quite often to solve problem (1), we have to assume that Y is a complete metric space, and T, S : X → Y are two mappings satisfying some type of contractivity, for instance see [1–5]. Some nonlinear problems arising from many areas of applied sciences can be formulated, from a mathematical point of view, as a coincidence problem (see, [1–3, 6, 7] and references within).

Once the existence of a solution to problem (1) is known, a central question consists to study if there exists an approximating sequence (xn) ⊆ X generated by an iterative procedure f(T, S, xn) such that the sequence (xn) converges to the coincidence point of T and S. Jungck [8] introduced the following iterative scheme: given x1 ∈ X, there exists a sequence (xn) in X such that Txn+1 = Sxn. This procedure becomes the Picard iteration when X = Y and T = Id, where Id is the identity map on X. In Jungck [8], the author proved that if (X, d) and (Y, ρ) are two complete metric spaces and T and S satisfy both that S(X) ⊆ T(X) and that for every x, y ∈ X the inequality d(Sx, Sy) ≤ κ d(Tx, Ty), with 0 ≤ κ < 1 holds, then (xn) converges to the unique coincidence point of T and S. Later, this type of convergence results were generalized for more general classes of contractive type mappings, see [6, 7, 9, 10] (to see another type of iterative schemes we can quote [10, 11]).

Since it is well known that the existence of a solution to problem (1) is, under appropriate conditions, equivalent to the existence of a fixed point for a certain mapping. In this article, we will use the Wardowski fixed point theorem [12] in order to show that problem (1) has a unique solution and that the Picard-Jungck iterative scheme converges to the unique coincidence point, moreover a rate of convergence for this scheme will also be given. Finally, we will apply these results to a general second order differential equation.

2. Notations and Preliminaries

Throughout this article ℝ+ and ℕ will denote the set of all non-negative real numbers and the set of all positive integers respectively.

Definition 2.1. Let X and Y be two nonempty sets and T, S:X → Y two mappings. If there exists x ∈ X such that Sx = Tx then x is said to be a coincidence point of S and T.

Definition 2.2. Let S and T be two self-mappings of a nonempty set X. The pair of mappings S and T is said to be weakly compatible if they commute at their coincidence points, that is, TSx = STx whenever Tx = Sx.

The following straightforward result states a relationship between coincidence points and common fixed points of two weakly compatible mappings, see Proposition 1.4 in Abbas and Jungck [9].

Lemma 2.1. Let S and T be weakly compatible self-mappings of a nonempty set X. If S and T have a unique coincidence point x, then x is the unique common fixed point of S and T.

Given k ∈ (0, 1), by k denote the set of all strictly increasing real functions f:(0, ∞) → ℝ satisfying the following conditions:

(F1) For each sequence {αn}n∈ℕ of positive numbers,

(F2) .

Definition 2.3. Let (X, d) be a complete metric space. A mapping T : X → X is said to be an F-contraction if there exist τ > 0 and f ∈ k such that, for all x, y ∈ X,

The following result will be the key in the proof of our results. This result was proved by Wardowski [12].

Theorem 2.1. [[12]] Let (X, d) be a complete metric space and let T : X → X be an F-contraction. Then T has a unique fixed point x* ∈ X and for every x0 ∈ X the sequence is convergent to x*.

3. Main results

3.1. Existence and Uniqueness

In this subsection we present a result which guarantees the existence and uniqueness of a solution to problem (1) when the mappings T and S satisfy a Wardowski's contractivity type condition.

Theorem 3.1. Let X be a nonempty set and let (Y, ρ) be a complete metric space. Assume that T, S:X → Y are two mappings satisfying the following conditions:

(i) T(X) is closed;

(ii) S(X) ⊆ T(X);

(iii) There exist τ > 0 and f ∈ k such that, for all x, y ∈ X,

Then, T and S have at least one coincidence point in X. If, moreover, T is one-to-one, then this coincidence point is unique.

Proof. Consider h : T(X) → 2T(X) given by h(x): = S(T−1x), where T−1x: = {ξ ∈ X:T(ξ) = x}. Notice that h is single-valued. Indeed, if u, v ∈ h(x) with u ≠ v, then by definition we know that there exists such that u = Sξu and v = Sξv. Since ρ(Sξu, Sξv) = ρ(u, v) > 0, from (3), we have that

which is a contradiction, because f is not defined at 0.

Therefore, h : T(X) → T(X) is a single valued map from T(X) into itself. Furthermore, h verifies Wardowski's contractive condition [12], since if 0 < ρ(h(x), h(y)) = ρ(S(T−1x), S(T−1y)), then by (3) we have that

that is, τ + f(ρ(h(x), h(y))) ≤ f(ρ(x, y)).

Bearing in mind that (Y, ρ) is complete and T(X) is closed, Wardowski's Theorem states that h has a unique fixed point y* ∈ T(X). Consider x* ∈ T−1y*. Then, by definition, we have that Sx* = S(T−1y*) = h(y*) = y* = Tx*, that is, x* is a coincidence point of T and S.

Now suppose that T is injective. If there exist x*, x′ ∈ X such that Sx* = Tx*, Tx′ = Sx′ and x* ≠ x′, then Sx* = Tx* ≠ Tx′ = Sx′ because T is injective. From (3), we obtain

i.e., τ ≤ 0 which is a contradiction. □

Corollary 3.1. Let X be a nonempty set and (Y, ρ) be a complete metric space. Assume that T, S : X → Y are two mappings such that:

(a) T(X) is closed;

(b) S(X) ⊆ T(X);

(c) There exist τ > 0 such that, for all x, y ∈ X,

Then, T and S have at least one coincidence point in X. If, moreover, T is one to one, then this coincidence point is unique.

Proof. From (c) it follows that

that is,

therefore

The above inequality can be written as

The last inequality means that T and S satisfy the conditions of Theorem 3.1 with respect to the function , which belongs to k for some . □

3.2. Picard-Juncgk's Iteration Process

In this subsection we present the results on the convergence for the Picard-Jungck scheme when the conditions of Theorem 3.1 are satisfied. Before giving our convergence result, we state the following lemma proved implicitly in the proof of Wardowski's Theorem [12].

Lemma 3.1. Let τ > 0 and f ∈ k with k ∈ (0, 1). If {γn}n∈ℕ is a sequence of real non-negative numbers satisfying τ + f(γn+1) ≤ f(γn) for all n ∈ ℕ, then the series is convergent.

Theorem 3.2. Let X be a nonempty set and (Y, ρ) be a complete metric space. If T, S : X → Y satisfy the three conditions of Theorem 3.1 and T is one-to-one, then given x1 ∈ X the iterative scheme Txn+1 = Sxn satisfies that the sequences {Txn}n∈ℕ and {Sxn}n∈ℕ converge to Tp = Sp, where p ∈ X is the unique coincidence point of T and S.

Proof. Notice that under these assumptions, Theorem 3.1 guarantees the existence and uniqueness of a coincidence point of T and S. Let x1 ∈ X. It is worth pointing out that the sequence {xn}n∈ℕ, implicitly defined as

is well-defined, since S(X) ⊆ T(X). Furthermore, from the injectiveness of T, there exists T−1:T(X) → X and, therefore, the sequence {xn}n∈ℕ can be explicitly defined by for all n ∈ ℕ.

If there exists n0 ∈ ℕ such that Sxn0 = Sxn0+1, then by (5) xn0+1 is a coincidence point of T and S. But, in this case, we have that Txn0+2 = Sxn0+1 = Txn0+1, which implies xn0+2 = xn0+1 because T is injective. Again applying (5), we deduce that Txn0+3 = Sxn0+2 = Txn0+1. Bearing in mind the injectiveness of T, we get xn0+3 = xn0+1. Hence, {xn}n>n0 is a constant sequence.

Thus, we can assume that Sxn ≠ Sxn+1 for all n ∈ ℕ. For each n ∈ ℕ, we define γn: = ρ(Sxn, Sxn+1). Thus, γn>0 for all n ∈ ℕ. Moreover, from (3) and (5), τ+f(γn+1) ≤ f(γn) for all n ∈ ℕ. By Lemma 3.1, the series is convergent. Then, {Sxn}n∈ℕ is a Cauchy sequence, since for m ≥ n,

Since T(X) is complete, there exists q ∈ T(X) such that Sxn → q as n → ∞. By (5), we also deduce that Txn → q as n → ∞. Since q ∈ T(X), there exists p ∈ X such that q = Tp. Let us see that Tp = Sp.

Notice that there exists n1 ∈ ℕ such that Sxn ≠ Sp for all n ≥ n1. Otherwise there exists a subsequence {Sxnk}nk∈ℕ such that Sxnk = Sp for all nk ∈ ℕ. In this case, Sp = Tp since Sxn → Tp as n → ∞.

Therefore, we can assume that Sxn ≠ Sp for all n ≥ n1. By the contractive condition (3), for each n ≥ n1,

Since τ > 0 and f is strictly increasing, we have that ρ(Sxn, Sp) < ρ(Txn, Tp) for all n ≥ n1. Taking limits and bearing in mind that Txn → Tp as n → ∞, we infer that Sxn → Sp as n → ∞. Then, Tp = Sp. □

We now state the convergence of the sequence {xn}n∈ℕ to the unique coincidence point of T and S.

Theorem 3.3. Let (X, d) and (Y, ρ) be two metric spaces, with Y being complete. Suppose that T, S : X → Y satisfy the three conditions of Theorem 3.1. If T is injective and T−1 is continuous, then the sequence {xn}n∈ℕ, defined by for each n ∈ ℕ, converges to the unique coincidence point of T and S.

Proof. Let p be the unique coincidence point of T and S, whose existence and uniqueness is guaranteed by Theorem 3.1. Fix x1 ∈ X. By Theorem 3.2, we know that {Txn}n∈ℕ and {Sxn}n∈ℕ converge to Tp = Sp. From the continuity of T−1 we conclude that

□

Notice that it is not easy to check the continuity of T−1. However, one can give some metric type condition for T which implies the continuity of T−1. In order to do this, we denote by the set of functions g:ℝ+ → ℝ+ such that, for any sequence {tn}n∈ℕ, implies . On one hand, it is easily seen that if g ∈ then g(t) > 0 for all t > 0. On the other hand, contains a large number of functions, because contains the set of all monotone nondecreasing real functions g:ℝ+ → ℝ+ such that g(t) = 0 if and only if t = 0, see [10, Lemma 2.2].

Corollary 3.2. Let (X, d) and (Y, ρ) be two metric spaces, with Y being complete. Suppose that T, S : X → Y satisfy the three conditions of Theorem 3.1. If there exists g ∈ such that

then the sequence {xn}n∈ℕ, defined by for each n ∈ ℕ, converges to the unique coincidence point of T and S.

Proof. It is sufficient to prove that T is one to one and T−1 is continuous. Notice first that (6) implies that T is one to one. Indeed, if Tx = Ty then g(d(x, y)) = 0 which implies that d(x, y) = 0, since g ∈ . Then, T−1 : T(X) → X is well-defined. We now see that T−1 is continuous. Let {un}n∈ℕ ⊆ T(X) be a sequence converging to u ∈ T(X). From (6), we have g(d(T−1v, T−1w)) ≤ ρ(v, w) for all v, w ∈ T(X). Then,

Since g ∈ , we deduce that as n → ∞. □

Remark 3.1. It is worth pointing out that the continuity of T−1 does not imply that (6) holds: Just take T:ℝ+ → ℝ+ defined by .

Remark 3.2. Since the identity mapping is weakly compatible with respect to any mapping, from Corollary 3.2, we recapture Theorem 2.1.

Corollary 3.3. Let (X.d) and (Y, ρ) be two metric spaces, with Y being complete. Assume that T, S : X → Y are two mappings satisfying the conditions of Corollary 3.1 and, in addition, that there exists g ∈ such that T : X → Y satisfies inequality (Equation 6). Then the sequence {xn}, defined by , converges to the unique coincidence point of T and S.

Proof. The proof of Corollary 3.1 shows that T and S satisfy the hypotheses of Corollary 3.2 with and therefore we obtain the result. □

3.3. Rate of Convergence

The idea given in Kohlenbach [13] allows us to introduce the concept of modulus of uniqueness for the coincidence problem as follows.

Definition 3.1. Let (X, d) and (Y, ρ) be two metric spaces and let T, S : X → Y be two mappings. A function ψ : (0, ∞) → (0, ∞) is said to be a modulus of uniqueness for the coincidence problem defined by T and S if, for any ε > 0, max{ρ(Tx, Sx), ρ(Ty, Sy)} < ψ(ε) implies that d(x, y) < ε.

Theorem 3.4. Let (X, d) and (Y, ρ) be two metric spaces. Suppose that T, S : X → Y satisfy the three conditions of Theorem 3.1 and also that there exists an increasing function g : (0, +∞) → (0, +∞) such that

If the function β : (0, +∞) → (0, +∞) defined by β(t): = t − f−1(f(t)−τ) is increasing then is a modulus of uniqueness for the coincidence problem defined by T and S.

Proof. Let ε > 0 and x, y ∈ X such that max {ρ(Tx, Sx), ρ(Ty, Sy)} < ψ(ε). Notice that

Then, β(ρ(Tx, Ty)) < 2ψ(ε) = β(g(ε)). Since β is increasing, we get ρ(Tx, Ty) < g(ε). From (7), we deduce that d(x, y) < ε because g is increasing. □

Remark 3.3. As a direct consequence of the above theorem, we can get a new result on generalized Ulam-Hyers stability of the coincidence problem (1).

Another consequence of Theorem 3.4 is the following result that states a rate of convergence for Picard-Juncgk's iteration process.

Theorem 3.5. Under the hypotheses of Theorem 3.4. Let {xn}n∈ℕ be the sequence defined by for each n ∈ ℕ. Let p ∈ X be some coincidence point of T and S. Then, for all n ≥ Φ(ε), we have that d(xn, p) < ε, where Φ : (0, +∞) → ℕ is given as

Proof. Fix ε > 0. By Theorem 3.4, if we prove that ρ(Txn, Sxn) < ψ(ε) for all n ≥ Φ(ε), then we are done, since in this case it is enough to take x = xn and y = p.

Let us prove that ρ(Txn, Sxn) < ψ(ε) for all n ≥ Φ(ε), i.e., ρ(Sxn−1, Sxn) < ψ(ε) for all n ≥ Φ(ε). From the proof of Theorem 3.2 we know that the sequence {γn}n∈ℕ, defined by γn: = ρ(Sxn, Sxn+1), satisfies

Since f is increasing and τ > 0, we have that {γn}n∈ℕ is strictly decreasing.

If γ1: = ρ(Sx1, Tx1) < ψ(ε), then γn < ψ(ε) for all n ≥ 1 = Φ(ε). Thus, we can assume that ψ(ε) ≤ γ1.

We claim that γΦ(ε) < ψ(ε). By contradiction, suppose that ψ(ε) ≤ γΦ(ε). Using (8), we obtain that (Φ(ε)−1)τ + f(γΦ(ε)) ≤ f(γ1). Bearing in mind that f is increasing, we deduce that (Φ(ε)−1)τ+f(ψ(ε)) ≤ f(γ1), which contradicts the definition of Φ(ε). Therefore, γΦ(ε) < ψ(ε). Since {γn}n∈ℕ is decreasing, we conclude that γn < ψ(ε) for all n ≥ Φ(ε). □

Corollary 3.4. Let (X, d) and (Y, ρ) be two metric spaces. If T, S:X → Y satisfy the condition of Corollary 3.3, then the function , where , is a modulus of uniqueness for the coincidence problem defined by T and S.

Proof. In this case, the proof of Corollary 3.1 shows that , and then it is clear that . The above facts imply that and then its derivative is , which says that β is an increasing function. Finally, by Theorem 3.4, we infer that is a modulus of uniqueness. □

4. An Application to Differential Equations

We consider the following problem associated to a general differential equation of second order with homogeneous Dirichlet condition:

where G:[a, b] × ℝ × ℝ → ℝ is certain known function satisfying the following two general conditions:

(H1) G is continuous in [a, b] × ℝ × ℝ;

(H2) there exist τ, μ > 0 and f ∈ k, for some k ∈ (0, 1), such that

for all t ∈ [0, 1], xi, yi ∈ ℝ, with i = 1, 2; where,

Let Y = ([a, b], ||·||∞) be the Banach space of the continuous functions u : [a, b] → ℝ, with its norm ||u||∞: = max{|u(t) : a ≤ t ≤ b}. In the linear space 2[a, b]: = {u : [a, b] → ℝ : u″ ∈ [a, b]} we consider the linear subspace X: = {u ∈ 2[a, b] : u(a) = u(b) = 0}. Notice that X endowed with the norm is a Banach space.

In order to prove the existence and uniqueness of a solution of (P) in 2[a, b], we need the following result attributed to Tumura [14], see [15, p. 80].

Lemma 4.1. For any u ∈ X we have that and . Moreover, the above inequalities are sharp, since they become equalities for the function u(t) = (t − a)(b − t).

Now we are able to state the main result of this section on the existence and uniqueness of a solution of (P).

Theorem 4.1. With the previous notation, suppose that: G : [a, b] × ℝ × ℝ → ℝ satisfies conditions (H1) and (H2). Then, problem (P) has a unique solution .

Proof. We define T, S : X → Y as Tu(t) = u″(t) and Su = G(t, u(t), u′(t)). In order to obtain the existence and uniqueness of the solution to the problem (P), we will see that T and S satisfy the conditions of Theorem 3.1. Notice that T is onto. Indeed, given w ∈ Y it is enough to consider

since in this case u ∈ X and Tu = w. Thus, assumptions (i) and (ii) in Theorem 3.1 hold. Let us prove that T and S satisfy (iii). Assume that u, v ∈ X with ||u − v||∞ ≠ 0. Then, there exists at least one t ∈ [a, b] such that u(t) ≠ v(t). Hence, by (H2),

the last inequality is obtained from Lemma 4.1 and because f is increasing. Thus, , that is, T and S satisfy (iii). From Theorem 3.1, T and S have a unique coincidence point in X, i.e., problem (P) has a unique solution .

Remark 4.1. Under the conditions of Theorem 4.1, applying Lemma 4.1 we obtain that , where

Then

(a) If we define g(t) = t/M, it is clear that T satisfies inequalities (Equations 6, 7). Therefore, by Corollary 3.2, we infer that for each u1 ∈ X, the sequence {un}n∈ℕ defined by

where , converges to us,

(b) If the function β : (0, ∞) → ℝ, defined by β(t): = t − f−1 (f(t) − τ), is increasing, Theorem 3.5 yields that for any ε > 0, ||un − us||* < ε for all n ≥ Φ(ε), where

which means that Φ given by (10) is a rate of convergence for {un} to us.

4.1. A Particular Case

Let G : [0, 1] × ℝ × ℝ → ℝ be a continuous function such that for every t ∈ [0, 1], and for all x, y ∈ ℝ the following inequality holds for some τ > 0,

Let us check that G satisfies condition (H2). Indeed, consider the function f:(0, ∞) → (−∞, 0) defined by It is clear that f−1 : (−∞, 0) → (0, ∞) is given by Therefore, taking μ = α1 = α2 = 1 we have:

which means that G satisfies condition (H2).

Example 4.1. The second order differential equation with homogeneous Dirichlet condition

has a unique classical solution.

To see that Equation (12) has a unique classical solution it is enough to show that the conditions of Theorem 4.1 are satisfied. Since Equation (12) can be rewritten as

where G : [0, 1] × ℝ × ℝ → ℝ is defined by

we are going to prove that G satisfies inequality (Equation 11). To do this, we notice first that the following elementary properties hold:

(1) the function φ : [0, ∞) → [0, ∞), , is increasing since

(2) φ is concave since

(3) since φ(0) = 0 and φ is concave, then it is sub-additive, that is φ(t + s) ≤ φ(t) + φ(s).

Since

With the above three properties, the above inequality can be written as follows

which means that the conditions of Theorem 4.1 are satisfied and therefore Equation (12) admits a unique classical solution.

Finally, let us give, by using expression (10), a rate of convergence for the iterative scheme given in Equation (9) concerning Equation (12). To apply Theorem 3.5, first we have to notice that the following facts hold:

1. f : (0, +∞) → (−∞, 0) is given by ,

2. f−1 : (−∞, 0) → (0, +∞) is .

3. g:[0, ∞) → [0, ∞) is given by g(t) = t,

4. τ = 1,

5.

6.

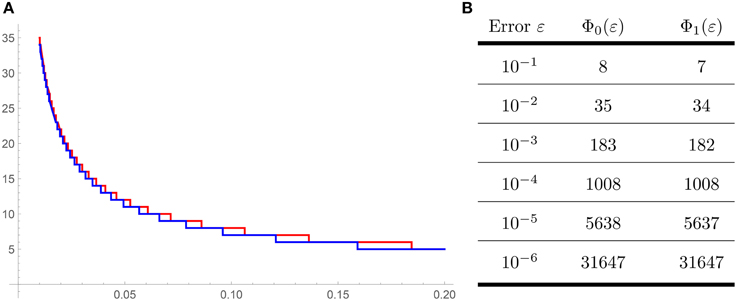

In Figure 1, we use the above facts and expression (Equation 10) to compute the number of iterations that we have to do to obtain an error less than ϵ = 10−k for k = 1, ⋯ , 6 and taking as starting points u1 = 0 and respectively.

Figure 1. (A) Red line is the ratio taking as a starting point u1 = 0 and blue line is the ratio for the starting point . (B) (The ratio of convergence Φ0 corresponds to u1 = 0, while Φ2 corresponds to ).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Part of this work was carried out while the first author was visiting the Department of Mathematical Analysis of the University of Valencia.

The research of the first author has been partially supported by MTM 2012-34847-C02-01 and P08-FQM-03453. The second author has been partially supported by MTM 2012-34847-C02-02.

References

1. Garcia-Falset J, Mleşnitţe O. Coincidence problems for generalized contractions. Appl Anal Discrete Math. (2014) 8:1–15. doi: 10.2298/AADM131031021F

2. Garcia-Falset J, Muñiz-Pérez O, Sadarangani K. Coincidence problems under contractive type conditions. Fixed Point Theory. (in press).

5. Mleşnite O. Existence and Ulam-Hyers stability results for coincidence problems. J Nonlinear Sci Appl. (2013) 6:108–16.

6. Berinde V. Common fixed points of noncommuting discontinuous weakly contractive mappings in cone metric spaces. Taiwan J Math. (2010) 14:1763–76.

7. Cakić N. Coincidence and common fixed point theorems for (φ, ϕ) weakly contractive mappings in generalized metric spaces. Filomat (2013) 27:1415–23. doi: 10.2298/FIL1308415C

8. Jungck G. Commuting mappings and fixed points. Am Math Month. (1976) 83:261–3. doi: 10.2307/2318216

9. Abbas M, Jungck G. Common fixed point results for noncommuting mappings without continuity in cone metric spaces. J Math Anal Appl. (2008) 341:416–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jmaa.2007.09.070

10. Ariza-Ruiz D, Garcia-Falset J. Iterative approximation to a coincidence point of two mappings. Appl Math Comp. (2015) 259:762–76. doi: 10.1016/j.amc.2015.03.007

11. Olaleru JO, Akewe H. On Multistep Iterative scheme for approximating the common fixed point of contractive-like operators. Inter J Math Math Sci. (2010) 2010:530964. doi: 10.1155/2010/530964

12. Wardowski D. Fixed points of a new type of contractive mappings in complete metric spaces. Fixed Point Theory Appl. (2012) 2012:1–6. doi: 10.1186/1687-1812-2012-94

13. Kohlenbach U. Applied Proof Theory. Proof Interpretations and their Use in Mathematics. Berlin; Heidelberg: Springer Monographs in Mathematics (2008).

Keywords: coincidence points, iterative methods, rate of convergence, common fixed points

MSC: 54H25, 47J25

Citation: Ariza-Ruiz D, Garcia-Falset J and Sadarangani K (2015) Wardowski conditions to the coincidence problem. Front. Appl. Math. Stat. 1:9. doi: 10.3389/fams.2015.00009

Received: 14 May 2015; Accepted: 31 July 2015;

Published: 31 August 2015.

Edited by:

Alexander Zaslavski, The Technion - Israel Institute of Technology, IsraelReviewed by:

Yekini Shehu, University of Nigeria, NigeriaSuthep Suantai, Chiang Mai University, Thailand

Prasit Cholamjiak, University of Phayao, Thailand

Copyright © 2015 Ariza-Ruiz, Garcia-Falset and Sadarangani. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jesus Garcia-Falset, Departament d'Anàlisi Matemàtica, Universitat de València, Dr. Moliner 50, 46100 Burjassot, València, Spain, garciaf@uv.es

David Ariza-Ruiz

David Ariza-Ruiz Jesus Garcia-Falset

Jesus Garcia-Falset Kishin Sadarangani

Kishin Sadarangani