- Graduate School of Bio-Applications and Systems Engineering, Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology, Koganei, Tokyo, Japan

While many Plusiinae species commonly secrete (Z)-7-dodecenyl acetate (Z7-12:OAc) as a key pheromone component, female moths of the rice looper (Plusia festucae) exceptionally utilize (Z)-5-dodecenyl acetate (Z5-12:OAc) to communicate with their partners. GC–MS analysis of methyl esters derived from fatty acids included in the pheromone gland of P. festucae showed a series of esters monounsaturated at the ω7-position, i.e., (Z)-5-dodecenoate, (Z)-7-tetradecenoate, (Z)-9-hexadecenoate (Z9-16:Me), and (Z)-11-octadecenoate (Z11-18:Me). By topical application of D3-labled palmitic acid (16:Acid) and stearic acid (18:Acid) to the pheromone glands, similar amounts of D3-Z5-12:OAc were detected. The glands treated with D13-labeled monoenoic acids (Z9-16:Acid and Z11-18:Acid), which were custom-made by utilizing an acetylene coupling reaction with D13-1-bromohexane, also produced similar amounts of D13-Z5-12:OAc. These results suggested that Z5-12:OAc was biosynthesized by ω7-desaturase with low substrate specificity, which could introduce a double bond at the 9-position of a 16:Acid derivative and the 11-position of an 18:Acid derivative. Additional experiments with the glands pretreated with an inhibitor of chain elongation supported this speculation. Furthermore, a comparative study with another Plusiinae species (Chrysodeixis eriosoma) secreting Z7-12:OAc indicated that the β-oxidation systems of P. festucae and C. eriosoma were different.

Introduction

About 160,000 lepidopteran species are known world wide, and each species is believed to establish a species-specific mating communication system for species conservation. Not only nocturnal moths but also diurnal moths utilize special sex pheromones as a chemical cue. Lepidopteran sex pheromones have been identified from more than 600 moth species and about three-quarters of them are composed of C10–C18 unsaturated fatty alcohols, their acetates, and aldehyde derivatives, including one, two, or three C=C bonds (Type I pheromones; Ando et al., 2004; Ando, 2011; El-Sayed, 2011). These components are biosynthesized from saturated fatty acyl intermediates, into which double bonds are introduced at definite positions by desaturases working in a pheromone gland (Jurenka, 2004). The double bonds locate at various positions, i.e., from the terminal methyl group to the next carbon to the functional group. In addition to the different chain lengths and kinds of terminal functional groups, the chemical structural varieties are attributed to the different positions of the double bonds (Ando et al., 2004).

Plusiinae is a well-assembled subfamily in Noctuidae, which is the biggest family in Lepidoptera, and includes many pest species secreting Type I pheromones. Since a pioneering study on the chemical communication of the cabbage looper, Trichoplusia ni (Berger, 1966), sex pheromones have been identified from 22 Plusiinae species (Ando, 2011; El-Sayed, 2011). Most of them secrete (Z)-7-dodecenyl acetate (Z7-12:OAc) as a main pheromone component and blend some structurally related compounds to make species-specific pheromones, suggesting that a primitive species in Plusiinae utilized Z7-12:OAc and speciated to many existing species while establishing the ability to produce new pheromone components. Z7-12:OAc is biosynthesized via Δ11-desaturation of a saturated C16 acyl compound (16:Acyl), probably a CoA-derivative of palmitic acid (16:Acid; Bjostad and Roelofs, 1983), and this key step has been confirmed by identification of the gene encoding Δ11-desaturase from T. ni (Knipple et al., 1998). The Δ11-desaturation is an important biosynthetic step because β-oxidation of the produced (Z)-11-hexadecenyl intermediate in different degrees yields a series of monoenyl compounds unsaturated at the ω5-position, such as (Z)-9-tetradecenyl acetate (Z9-14:OAc) and (Z)-5-decenyl acetate (Z5-10:OAc). Among the Plusiinae species, Z9-14:OAc is secreted by Macdunnoughia confusa, and Z5-10:OAc is secreted by Anadevidia peponis as a minor pheromone component (Inomata et al., 2000).

On the other hand, the sex pheromone of the rice looper, Plusia festucae, is composed of (Z)-5-dodecenyl acetate (Z5-12:OAc) as a main component and (Z)-7-tetradecenyl acetate (Z7-14:OAc) as a minor component (Ando et al., 1995). Both components include a double bond at the ω7-position, and the female moths produced no pheromone components unsaturated at the ω5-position. This exceptional Plusiinae pheromone is noteworthy, and we are interested in the biosynthetic pathway of the ω7-unsaturated components. Based on the information on the desaturation of many lepidopteran sex pheromones (Jurenka, 2004), we speculated that the P. festucae pheromone is produced by Δ9-desaturation of 16:Acyl or Δ11-desaturation of 18:Acyl. To clarify the pathway in P. festucae, we analyzed fatty acids in the pheromone glands by GC–MS at the start of the study. Next, deuterated C16 and C18 saturated and monoenoic fatty acids were treated to the pheromone glands, and the manner in which they were incorporated into Z5-12:OAc was compared. The results suggested that both desaturation made a contribution. The incorporation was also examined with a pheromone gland pretreated with an inhibitor of chain elongation to eliminate the possibility of the conversion of 16:Acid into 18:Acid. Furthermore, a similar biosynthetic experiment was carried out using another Plusiinae species, Chrysodeixis eriosoma, which secretes Z7-12:OAc as a main pheromone component (Komoda et al., 2000). Incorporation of deuterium was observed only in C. eriosoma females treated with the C16 acids, indicating different β-oxidation systems in P. festucae and C. eriosoma females.

Materials and Methods

Insects

Larvae of three Plusiinae species (P. festucae, C. eriosoma, and A. peponis) were collected in a paddy field or a vegetable field of Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology (Fuchu, Tokyo). The P. festucae larvae were also collected in a paddy field in Yamagata Prefecture. Rearing for successive generations was separately carried out on an artificial diet consisting mainly of kidney beans (Kawasaki et al., 1987) at 25°C under a 16L–8D cycle. The female pupae were separated from the males, and 2- to 3-day-old virgin females were used for experiments. Their sex pheromones are composed of the following monoenyl compounds: P. festucae, Z5-12:OAc, Z7-14:OAc, and Z5-12:OH (100:15:6; Ando et al., 1995); C. eriosoma, Z7-12:OAc and Z9-12:OAc (17:3; Komoda et al., 2000); A. peponis, Z7-12:OAc, Z5-10:OAc, and Z7-12:OH (10:5:1; Inomata et al., 2000).

Lipid Extraction and Derivatization

From 10 pheromone glands removed from the females of each species, lipids were extracted with a mixed solvent of chloroform and methanol (v/v = 2:1) and used for basic hydrolysis to yield fatty acids. After purification by preparative TLC, the free acids were converted to esters by diazomethane and quantitatively analyzed by GC–MS. The fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) of P. festucae were also analyzed after derivatization with dimethyl disulfide (DMDS; Buser et al., 1983). The FAMEs were dissolved in a mixture of DMDS (50 μl) and diethyl ether (100 μl) including iodine (500 μg) and then warmed at 40°C overnight. The crude products, which were treated with a 5% sodium thiosulfate solution (0.5 ml), were extracted with hexane and analyzed by GC–MS.

Analytical Instruments

1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded by a Jeol Delta 2 Fourier transform spectrometer (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) at 399.8 and 100.5 MHz, respectively, for CDCl3 solutions containing TMS as an internal standard. GC–MS was conducted in the EI mode (70 eV) with an HP5973 mass spectrometer system (Hewlett-Packard) equipped with a split/splitless injector. A DB-23 column (0.25 mm ID × 30 m, 0.25 μm film, J & W Scientific, Folsom, CA, USA) was commonly used for analyses of the pheromone components and FAMEs, except for DMDS adducts, which were analyzed with an HP-5 column (0.25 mm ID × 30 m, 0.25 μm film, Hewlett-Packard, Wilmington, DE, USA). The temperature program for the DB-23 column was 80°C for 1 min and 8°C/min to 220°C, and that for HP-5 column was 100°C for 2 min, 15°C/min to 280°C, and held for 15 min. The carrier gas was He.

Deuterium-Labeled Precursors

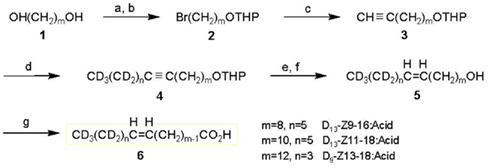

[16,16,16-D3]Palmitic acid (D9-16:Acid, 99.7 atom% of D) and [18,18,18-D3]stearic acid (D3-18:Acid, 99.7 atom% of D) were purchased from ISOTEC Inc. The synthesis of [13,13,14,14,15,15,16,16,16-D9](Z)-11-hexadecenoic acid (D9-Z11-16:Acid) has been reported (Ando et al., 1998). Other deuterated monoenyl fatty acids were synthesized by the routes described below (shown in Figure 1).

Figure 1. Synthetic routes to deuterated monoenyl acids (6); D13-(Z)-9-hexadecenoic acid (D13-Z9-16:Acid, m = 8, n = 5), D13-(Z)-11-octadecenoic acid (D13-Z11-18:Acid, m = 10, n = 5), and D9-(Z)-13-octadecenoic acid (D9-Z13-18:Acid, m = 12, n = 3). Reagents: a, HBr; b, 3,4-dihydro-2H-pyran; c, LiC≡CH·EDA/DMSO; d, (1) BuLi/THF, (2) CD3(CD2)nBr/HMPA; e, H2/Pd-BaSO4-quinoline/hexane; f, p-TsOH/EtOH; g, Jones reagent/acetone-H2O.

D13-Z9-16:Acid

[11,11,12,12,13,13,14,14,15,15,16,16,16-D13](Z)-9-Hexadecenoic acid was prepared starting from 1,8-octanediol (1, m = 8). By half-bromination with HBr and protection of the remaining hydroxyl group by dihydropyran, this alcohol was converted into the THP ether of 8-bromooctan-1-ol (2, m = 8). The bromide was treated with lithium acetylide and the produced terminal acetylene compound (3, m = 8) was coupled with D13-1-bromohexane (98 atom% of D, ISOTEC, Inc., OH, USA) to yield a hexadecyne derivative (4, m = 8, n = 5) that incorporated D13. The triple bond of 4 was partially reduced to a double bond under hydrogen gas with a Pd–BaSO4 catalyst poisoned with quinoline, and D13-(Z)-9-pentadecen-1-ol (5, m = 8, n = 5) was obtained after cleavage of the THP protective group. This alcohol was oxidized with the Jones reagent to yield the D13-Z9-16:Acid (5, m = 8, n = 5). NMR (δ ppm); 1H: 1.30 (8H, broad), 1.63 (2H, tt, J = 7.5, 7.5 Hz), 2.02 (2H, dt, J = 7, 7 Hz), 2.35 (2H, t, J = 7.5 Hz), 5.34 (2H, m), 13C: 24.7, 27.2, 29.1 (×2), 29.2, 29.7, 34.1, 129.8, 130.0, 180.2. GC–MS of methyl ester: Rt 13.75 min, m/z 281 (M+, 11%), 249 (38%), 74 (100%).

D13-Z11-18:Acid

[13,13,14,14,15,15,16,16,17,17,18,18,18-D13](Z)-11-Octadecenoic acid was synthesized starting from 1,10-decanediol (1, m = 10) via a deuterated 11-octadecyne derivative (4, m = 10, n = 5), which was prepared by a coupling reaction between an acetylene compound (3, m = 10) and D13-1-bromohexane. NMR (δ ppm); 1H: 1.29 (12H, broad), 1.64 (2H, tt, J = 7.5, 7.5 Hz), 2.01 (2H, dt, J = 7, 7 Hz), 2.34 (2H, t, J = 7.5 Hz), 5.34 (2H, m), 13C: 24.7, 27.2, 29.1(×2), 29.2 (×3), 29.4, 29.5, 29.8, 34.0, 129.9 (×2), 180.0. GC–MS of methyl ester: Rt 15.82 min, m/z 309 (M+, 10%), 277 (33%), 74 (100%).

D9-Z13-18:Acid

[15,15,16,16,17,17,18,18,18-D9](Z)-13-Octadecenoic acid was synthesized starting from 1,12-dodecanediol (1, m = 10) via a deuterated 13-octadecyne derivative (4, m = 12, n = 3). This intermediate was prepared by a coupling reaction between an acetylene compound (3, m = 12) and D9-1-bromobutane, which was derived from D10-1-butanol (98 atom% of D, ISOTEC, Inc.). NMR (δ ppm); 1H: 1.29 (14H, broad), 1.64 (2H, tt, J = 7.5, 7.5 Hz), 2.01 (2H, dt, J = 7, 7 Hz), 2.34 (2H, t, J = 7.5 Hz), 5.34 (2H, m), 13C: 24.7, 27.2, 29.1, 29.2 (×2), 29.4, 29.5, 29.8, 34.0, 129.9 (×2), 180.1. GC–MS of methyl ester: Rt 15.80 min, m/z 305 (M+, 12%), 273 (41%), 74 (100%).

Application of Labeled Precursors and an Elongation Inhibitor

Deuterated fatty acids were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at a concentration of 20 μg/μl, and 1 μl of each solution was topically applied to the pheromone glands of 2-day-old virgin females of P. festucae and C. eriosoma 4 h after lights-off. Pheromone components were extracted from the glands with hexane 3 h after the application, and the extract was analyzed by GC–MS under a cyclic scan mode (from m/z 40 to m/z 500) or a selected ion monitoring (SIM) mode. The quantitative analysis of labeled and unlabeled compounds was accomplished by peak areas of [M-60]+ ions, referring to calibration curves made with authentic standards. Five groups of the extract from five females were used for each treatment.

Conversion of D3-16:Acid was also examined with the P. festucae females, which lost their ability for chain elongation through treatment with an inhibitor, 2-hexadecynoic acid (Wood and Lee, 1981). The acid was synthesized by an acetylene coupling reaction between 1-pentadecyne and CO2 in a similar manner as that reported for the preparation of 2-octadecynoic acid (Renobales et al., 1986). One microliter of the DMSO solution of the acid at a 20 μg/μl concentration was topically applied to each pheromone gland 30 min before treatment with D3-16:Acid, and D3-Z5-12:OAc produced in the gland was quantitated by GC–MS.

Results

Fatty Acids in the Pheromone Glands

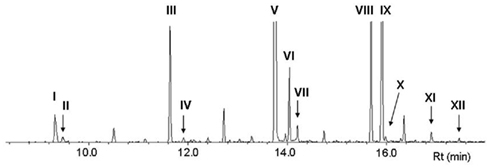

Figure 2 shows the GC–MS analysis (total ion chromatogram, TIC) of FAMEs derived from lipids in the pheromone gland of P. festucae females. In addition to a large amount of esters derived from generally observed fatty acids, such as methyl palmitate (V, Rt 13.74 min), stearate (VIII, Rt 15.63 min), and oleate (IX, Z9-18:Me, Rt 15.89 min), esters of several monoenyl acids were detected. Methyl (Z)-5-dodecenoate (II, Rt 9.48 min) and (Z)-7-tetradecenoate (IV, Rt 11.91 min) are expected to be direct precursors of the pheromone components of Z5-12:OAc and Z7-14:OAc, respectively. The Rts of II and IV coincided with authentic standards, and their chemical structures were further confirmed by mass spectra of DMDS adducts, i.e., characteristic fragment ions of DMDS adducts of II at m/z 161 and 145 and IV at m/z 189 and 145 revealed the double bond at the 5- and 7-positions, respectively. This DMDS experiment also confirmed the structure of other esters of monoenyl acids, methyl (Z)-9-hexadecenoate (VI, Z9-16:Me, Rt 14.04 min), (Z)-11-hexadecenoate (VII, Z11-16:Me, Rt 14.20 min), and (Z)-11-octadecenoate (X, Z11-18:Me, Rt 15.97 min). Among the esters corresponding to the two possible candidates for a biosynthetic intermediate with a long chain, the titer of Z9-16:Me was remarkably higher than that of Z11-18:Me.

Figure 2. GC–MS analysis (total ion chromatogram, TIC) of fatty acid methyl esters derived from the lipids in pheromone glands of Plusia festucae. I, methyl laurate (12:Me); II, methyl (Z)-5-dodecenoate (Z5-12:Me); III, methyl myristate (14:Me); IV, methyl (Z)-7-tetradecenoate (Z7-14:Me); V, methyl palmitate (16:Me); VI, methyl (Z)-9-hexadecenoate (Z9-16:Me); VII, methyl (Z)-11-hexadecenoate (Z11-16:Me); VIII, methyl stearate (18:Me); IX, methyl oleate (Z9-18:Me); X, methyl (Z)-11-octadecenoate (Z11-18:Me); XI, methyl linoleate (Z9,Z12-18:Me); XII, methyl linolenate (Z9,Z12,Z15-18:Me).

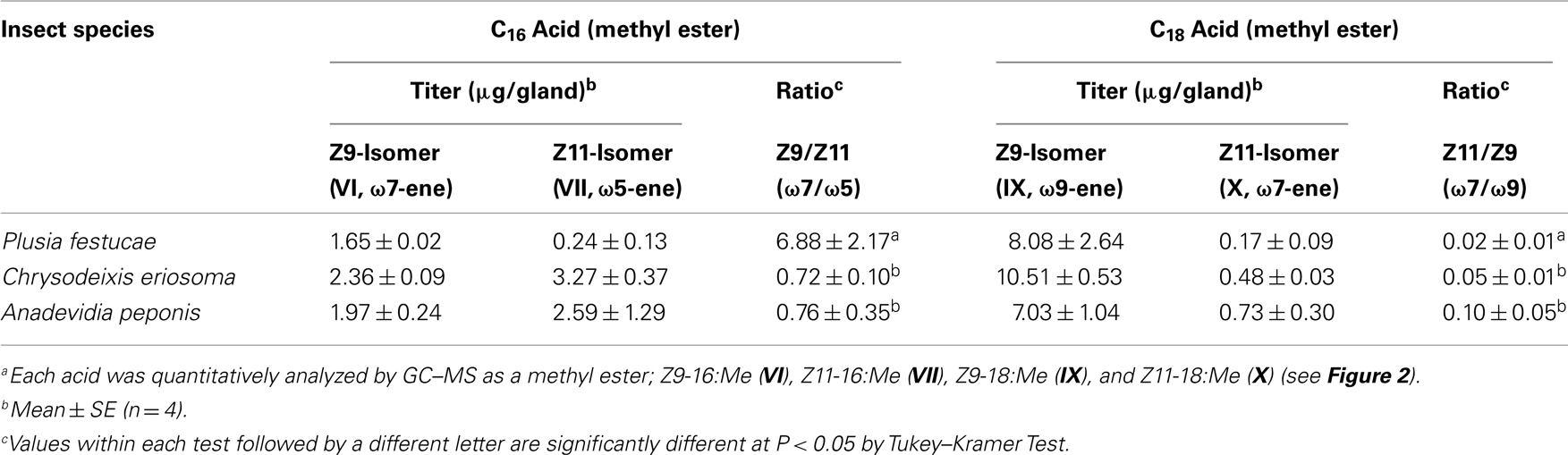

To understand the characteristic profile of FAMEs in P. festucae, the contents of C16 and C18 monoenyl acids were compared with those included in pheromone glands of the other two Plusiinae species, C. eriosoma and A. peponis (Table 1). These two species, which produce Z7-12:OAc as a main pheromone component, included more abundant Z11-16:Me than P. festucae, indicating Δ11-desaturation of 16:Acid as a key step in their 7-12:OAc biosyntheses. On the other hand, while the titer of Z9-16:Me in P. festucae was lower than those of the two species, the ratio of Z9-16:Me to Z11-16:Me was notably higher than that of the others. Both the titer of Z11-18:Me and its ratio to Z9-18:Me in P. festucae were smaller than those of the other species.

Table 1. Composition of monounsaturated fatty acids in the pheromone glands of three Plusiinae speciesa.

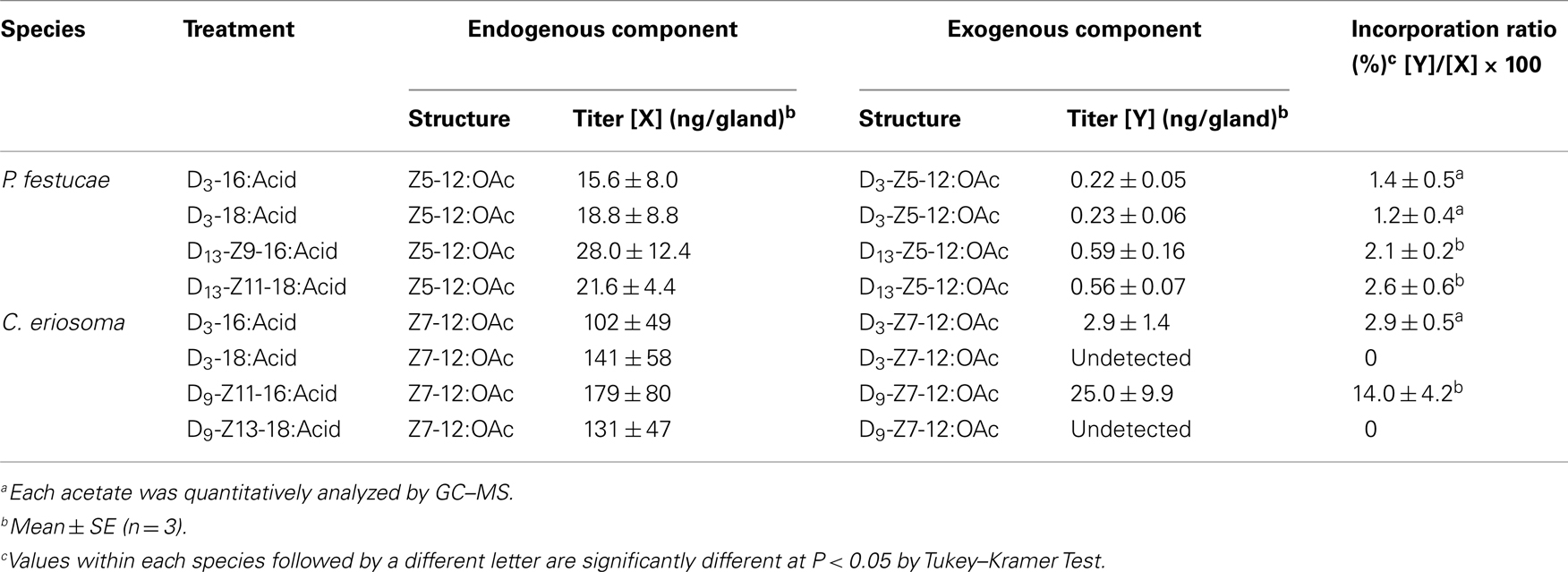

Incorporation of Labeled Acids into the P. festucae Pheromone

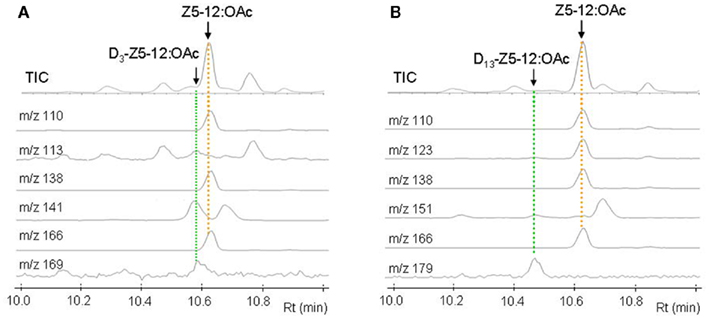

Figure 3 shows GC–MS analysis (TIC and mass chromatograms) of the extracts, which were prepared from the glands treated with deuterated C16 acids. In addition to endogenous Z5-12:OAc (Rt 10.63 min) monitored by ions at m/z 166, 138, and 110, ion peaks of m/z 169, 141, and 113 at 10.58 min suggested the production of D3-Z5-12:OAc by the topical application of D3-16:Acid (Figure 3A). In the case of D13-Z9-16:Acid, an ion peak of m/z 179 at 10.47 min suggested the production of D13-Z5-12:OAc (Figure 3B). Ion peaks of m/z 151 and 123 at 10.47 min, which were diagnostic for D13-Z5-12:OAc, were very small because the fragment ions were also produced by Z5-12:OAc and an unknown component. By treatment with D3-18:Acid and D13-Z11-18:Acid, the corresponding deuterated pheromone components were detected in the pheromone gland extracts. Table 2 shows the titers of unlabeled endogenous and deuterated exogenous pheromone components. The titers of D3-Z5-12:OAc in the pheromone glands treated with D3-16:Acid and D3-18:Acid were almost equal. The titers of D13-Z5-12:OAc derived from D13-Z9-16:Acid and D13-Z11-18:Acid were also almost equal. The incorporation ratios of D13-Z9-16:Acid and D13-Z11-18:Acid were higher than those of D3-16:Acid and D3-18:Acid.

Table 2. Titers of endogenous and exogenous pheromone components in the sex pheromone glands of Plusia festuca e and Chrysodeixis eriosom a females, which were treated with deuterated fatty acidsa.

Figure 3. GC–MS analysis of pheromone gland extracts of Plusia festucae females which were treated with D3-palmitic acid [D3-16:Acid (A)] and D13-(Z)-9-hexadecenoic acid [D13-Z9-16:Acid (B)]. The mass chromatograms indicated the following unlabeled and labeled pheromone components; Z5-12:OAc by the ions at m/z 166, 138, and 110, D3-Z5-12:OAc by the ions at m/z 169, 141, and 113, and D13-Z5-12:OAc by the ions at m/z 179, 151, and 123.

Effect of 2-Hexadecynoic Acid on Pheromone Biosynthesis

The incorporation of D3-16:Acid and D13-Z9-16:Acid was examined with the P. festucae glands pretreated with 2-hexadecynoic acid. The GC–MS analysis of the pheromone gland extracts showed the following titers of deuterated pheromone components and the incorporation ratios; D3-Z5-12:OAc (0.25 ± 0.09 ng/gland, 1.5 ± 0.7%, n = 3) from D3-16:Acid and D13-Z5-12:OAc (0.48 ± 0.22 ng/gland, 2.0 ± 0.8%, n = 3) from D13-Z9-16:Acid. These values were similar to those in the glands untreated with the inhibitor (Table 2), indicating that the chain elongation inhibitor did not affect the pheromone biosynthesis.

Incorporation of Labeled Acids into the C. eriosoma Pheromone

Experiments with labeled acids were also carried out with C. eriosoma females (Table 2). While D3-16:Acid was converted into D3-Z7-12:OAc, the labeled pheromone was not detected in the pheromone gland treated with D3-18:Acid. Similarly, while D9-Z11-16:Acid was converted into D9-Z7-12:OAc, the labeled pheromone was not detected in the pheromone gland treated with D9-Z13-18:Acid. The titer of D9-Z7-12:OAc was higher than that of D3-Z7-12:OAc. The incorporation ratio of D3-16:Acid was about five times higher than that of D9-Z11-16:Acid.

Discussion

In Lepidoptera, biosynthesis of Type I pheromones has been studied with several species and the results have proposed the following pathway operating in pheromone glands; formation of saturated fatty acyl compounds from acetyl CoA → desaturation → chain shortening or elongation → reduction of the acyl moiety to a hydroxyl group → acetylation of alcohols or oxidation to aldehydes (Jurenka, 2004). Pheromone glands usually include unsaturated fatty acyl intermediates, and they have been detected by GC–MS analysis of FAMEs from lipids in the glands. For example, Z11-16:Me and Z9-14:Me were found in FAMEs derived from lipids in T. ni females in addition to Z7-12:Me, which possessed the same chain structure as the main pheromone component (Z7-12:OAc; Bjostad and Roelofs, 1983; Roelofs and Bjostad, 1984). The key step for the biosynthesis in T. ni is Δ11-desaturation (ω5-desaturation) of 16:Acyl, and Z11-16:Me is the main ester derived from the pheromone gland lipids. Z11-16:Me was not the longest one among the esters of monoenoic acids. A trace amount of the ester of a C18 acid unsaturated at the ω5-position (Z13-18:Me) was detected and estimated to be produced by chain elongation of a Z11-16:Acyl intermediate.

On the other hand, a series of acyl intermediates unsaturated at the ω7-position was found in the lipids of the P. festucae females, which secreted Z5-12:OAc as a main pheromone component (Figure 2). Z9-16:Me is most abundantly included among the esters unsaturated at the ω7-position and the ratio of Z9-16:Me to Z11-16:Me detected in P. festucae is higher than those of other Plusiinae species, C. eriosoma and A. peponis (Table 1), which secrete Z7-12:OAc as a main pheromone component, as T. ni does. The data suggest that Z9-16:Acyl, which is produced by Δ9-desaturation (ω7-desaturation) of 16:Acyl, is a key biosynthetic intermediate of Z5-12:OAc. The content of Z11-18:Me is very small in P. festucae, and the ratio of Z11-18:Me to Z9-18:Me detected in P. festucae was also smaller than those in the other two Plusiinae species (Table 1). We speculated that Z11-18:Me might not be derived from a key biosynthetic intermediate of P. festucae, similarly to Z13-18:Me found in the FAMEs of T. ni females.

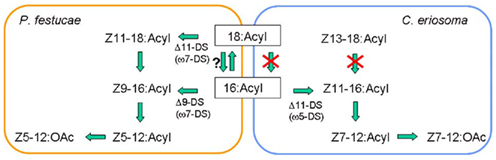

The biosynthetic pathway of Z5-12:OAc was confirmed by experiments with labeled fatty acids (Table 2). By topical application of D3-16:Acid and D13-Z9-16:Acid, D3-Z5-12:OAc and D13-Z5-12:OAc were respectively produced in the pheromone glands of P. festucae. The incorporation ratio of D13-Z9-16:Acid was higher than that of D3-16:Acid, supporting the desaturation step of 16:Acyl. Moreover, D3-18:Acid and D13-Z11-18:Acid were also incorporated into Z5-12:OAc. The incorporation ratios of D3-16:Acid and D3-18:Acid were not significantly different, and those of D13-Z9-16:Acid and D13-Z11-18:Acid are also similar. These results indicate that the above speculation for Z11-18:Me is incorrect. The very low content of Z11-18:Me suggests the rapid β-oxidation of Z11-18:Acyl. Thus, we concluded that not only Δ9-desaturation of 16:Acyl but also Δ11-desaturation of 18:Acyl are at work in the pheromone biosynthesis in the P. festucae females, as shown in Figure 4, if D3-16:Acid is not easily converted into D3-18:Acid in the pheromone glands. Since this chain elongation seems to be a common reaction, we examined the incorporation of D3-16:Acid using females pretreated with 2-hexadecynoic acid. This acetylene compound is a known inhibitor of chain elongation of 16:Acid (Wood and Lee, 1981). The inhibitor did not affect the incorporation in P. festucae, indicating that D3-16:Acid was desaturated without elongation and D3-Z9-16:Acid produced from D3-16:Acid was converted into D3-Z5-12:OAc (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Proposed biosynthetic pathways for the pheromone components, Z5-12:OAc and Z7-12:OAc, produced by the Plusiinae females. Experiments using deuterated fatty acids revealed that Z5-12:OAc was biosynthesized via ω7-desaturation (ω7-DS) of 18:Acyl and 16:Acyl in the pheromone gland of Plusia festucae and Z7-12:OAc was biosynthesized via ω5-desaturation (ω5-DS) of 16:Acyl in the pheromone gland of Chrysodeixis eriosoma. The β-oxidation systems for the pheromone biosynthesis of the two Plusiinae species were different.

As a comparative study, the biosynthesis of Z7-12:OAc in C. eriosoma was examined with labeled fatty acids (Table 2). The incorporation ratios of the deuterated C16 acids demonstrated the Δ11-desaturation of 16:Acyl as a key step similar to T. ni and other Plusiinae species (Komoda et al., 2000). On the contrary, deuterated C18 acids were not incorporated into the pheromone. Chain shortening of the C18 acids did not proceed in the pheromone gland of C. eriosoma, and it was interestingly revealed that the β-oxidation systems of P. festucae and C. eriosoma were different. The ability of β-oxidation of the C18 chain is not necessary for the C. eriosoma females and the inability might fit their pheromone biosynthesis. The silkworm (Bombyx mori) secreted C16 dienyl alcohol (bombykol) as a sex pheromone. Among a series of labeled fatty acids with a saturated C12-C18 chain, only 16:Acid was reliably incorporated into the bombykol (Ando et al., 1986). The other free acids did not enter into the biosynthetic pathway of bombykol. Although it is difficult to generalize, chain shortening and elongation of exogenous free acids do not seem to happen easily in the B. mori females. If the enzymes in the pheromone glands of P. festucae perform only a minimum necessary function, our experiment with the labeled acids clearly revealed their contribution to both types of desaturation in pheromone production.

In Plusiinae, Thysanoplusia intermixta females secrete a mixture of Z7-12:OAc and (5E,7Z)-5,7-dodecadienyl acetate (E5,Z7-12:OAc) for mating communication (Ando et al., 1998). The biosynthesis of the dienyl component was also investigated with several deuterated acids (Ono et al., 2002). While the double bond at the 5-position in the monoenyl pheromone of P. festucae is introduced at an early stage of the biosynthesis, probably just after construction of C16 and C18 saturated fatty acids, desaturation at the same position in the dienyl pheromone of T. intermixta is achieved on Z7-12:Acyl, which is produced by Δ11-desaturation of 16:Acyl and β-oxidation of the produced Z11-16:Acyl intermediate. This Δ5-desaturation is, in other words, ω7-desaturation. Some species in Plusiinae secrete pheromone components produced by ω3-desaturation, such as Z9-12:OAc of C. eriosoma and Z7-10:OAc of Diachrysia chrysitis (Löfstedt et al., 1994). In these species, Δ13-desaturation of 16:Acyl and Δ11-desaturation of 14:Acyl might proceed. Experimental proof for the actual substrate of ω3-desaturase is anticipated.

Whereas some Plusiinae species produce more than 10 components, only two or three compounds are essential for male attraction. Based on the chemical structures of these primary components, we have classified Plusiinae pheromones into nine groups (Ando et al., 2004; Inomata et al., 2005). All monoenyl components include the double bond at the ω3-, ω5-, or ω7-position; thus, the pheromones are produced by a combination of one of three desaturases and specific β-oxidation enzyme(s). Genes of the desaturases expressed specifically in a pheromone gland have been characterized from more than 20 lepidopteran species (Jurenka, 2004; Wang et al., 2010; Fujii et al., 2011). While the first identification of the desaturase for pheromone biosynthesis of moths was accomplished with T. ni (Knipple et al., 1998), the enzymes have unfortunately not been identified from any other Plusiinae species. In addition to providing insights on the chemical structures and biosynthetic pathways of the sex pheromones, systematic studies of the enzymes acting in the Plusiinae species would clarify speciation of this subfamily. The Plusiinae pheromones might be one of the most profitable targets for gaining an understanding of the evolution of moth species, and, therefore, further comprehensive studies are anticipated.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Ando, T. (2011). Internet Database. Available at http://www.tuat.ac.jp/~antetsu/LepiPheroList.htm

Ando, T., Arima, R., Mori, A., and Uchiyama, M. (1986). Incorporation of 14C-fatty acids into bombykol, a female sex pheromone of the silkworm moth. Agric. Biol. Chem. 50, 1093–1095.

Ando, T., Inomata, S., Shimada, R., Nomura, M., Uehara, S., and Pu, G.-Q. (1998). Sex pheromones of Thysanoplusia intermixta and T. orichalcea: identification and field tests. J. Chem. Ecol. 24, 1105–1116.

Ando, T., Inomata, S., and Yamamoto, M. (2004). Lepidopteran sex pheromones. Top. Curr. Chem. 239, 51–96.

Ando, T., Ohno, R., Kokuryu, T., Funayoshi, A., and Nomura, M. (1995). Identification of female sex pheromone components of rice looper, Plusia festucae (L.), (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). J. Chem. Ecol. 21, 1181–1190.

Berger, R. S. (1966). Isolation, identification, and synthesis of the sex attractant of the cabbage looper, Trichoplusia ni. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 59, 767–771.

Bjostad, L. B., and Roelofs, W. L. (1983). Sex pheromone biosynthesis in Trichoplusia ni: key steps involve delta-11 desaturation and chain-shortening. Science 220, 1387–1389.

Buser, H.-R., Arn, H., Guerin, P., and Rauscher, S. (1983). Determination of double bond position in mono-unsaturated acetates by mass spectrometry of dimethyl disulfide adducts. Anal. Chem. 55, 818–822.

El-Sayed, A. M. (2011). Internet Database. Available at http://www.pherobase.com/

Fujii, T., Ito, K., Tatematsu, M., Shimada, T., Katsma, S., and Ishikawa, Y. (2011). Sex pheromone desaturase functioning in a primitive Ostrinia moth is cryptically conserved in congeners’ genomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 7102–7106.

Inomata, S., Komoda, M., Watanabe, H., Nomura, M., and Ando, T. (2000). Identification of sex pheromones of Anadevidia peponis and Macdunnoughia confusa, and field tests of their role in reproductive isolation of closely related Plusiinae moths. J. Chem. Ecol. 26, 443–454.

Inomata, S., Watanabe, A., Nomura, M., and Ando, T. (2005). Mating communication systems of four Plusiinae species distributed in Japan: identification of the sex pheromones and field evaluation. J. Chem. Ecol. 31, 1429–1442.

Kawasaki, K., Ikeuchi, M., and Hidaka, T. (1987). Laboratory rearing method for Acanthoplusia agnate (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) without change of artificial diet. Jpn. J. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 31, 78–80.

Knipple, D. C., Rosenfield, C.-L., Miller, S. J., Liu, W., Tang, J., Ma, P. W. K., and Roelofs, W. L. (1998). Cloning and functional expression of a cDNA encoding a pheromone gland-specific acyl-CoA Δ11-desaturase of the cabbage looper moth, Trichoplusia ni. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 15287–15292.

Komoda, M., Inomata, S., Ono, A., Watanabe, H., and Ando, T. (2000). Regulation of sex pheromone biosynthesis in three Plusiinae moths: Macdunnoughia confusa, Anadevidia peponis, and Chrysodeixis eriosoma. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 64, 2145–2151.

Löfstedt, C., Hansson, B. S., Tóth, M., Szöcs, G., Buda, V., Bengtsson, M., Ryrholm, N., Svensson, M., and Priesner, E. (1994). Pheromone differences between sibling taxa Diachrysia chrysitis (Linnaeus, 1758) and D. tutti (Kostrowicki, 1961) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). J. Chem. Ecol. 20, 91–109.

Ono, A., Imai, T., Inomata, S., Watanabe, A., and Ando, T. (2002). Biosynthetic pathway for production of a conjugated dienyl sex pheromone of a Plusiinae moth, Thysanoplusia intermixta. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 32, 701–708.

Renobales, M., Wakayama, E. J., Halarnkar, P. P., Reitz, R. C., Pomonis, J. G., and Blomquist, G. J. (1986). Inhibition of hydrocarbon biosynthesis in the housefly by 2-octadecynoate. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 3, 75–86.

Roelofs, W., and Bjostad, L. (1984). Biosynthesis of lepidopteran pheromones. Bioorg. Chem. 12, 279–298.

Wang, H.-L., Lienard, M. A., Zhao, C.-H., Wang, C.-Z., and Löfstedt, C. (2010). Neofunctionalization in an ancestral insect desaturase lineage led to rare Δ6 pheromone signals in the Chinese tussah silkworm. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 40, 742–751.

Keywords: pheromone biosynthesis, Lepidoptera, Noctuidae, incorporation of deuterated precursors, ω7-desaturation, monoenyl fatty acid

Citation: Watanabe H, Matsui A, Inomata S-i, Yamamoto M and Ando T (2011) Biosynthetic pathway for sex pheromone components produced in a Plusiinae moth, Plusia festucae. Front. Endocrin. 2:74. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2011.00074

Received: 26 September 2011; Paper pending published: 18 October 2011;

Accepted: 26 October 2011; Published online: 14 November 2011.

Edited by:

Shogo Matsumoto, Advanced Science Institute – RIKEN, JapanReviewed by:

Shogo Matsumoto, Advanced Science Institute – RIKEN, JapanRussell Jurenka, Iowa State University, USA

Copyright: © 2011 Watanabe, Matsui, Inomata, Yamamoto and Ando. This is an open-access article subject to a non-exclusive license between the authors and Frontiers Media SA, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in other forums, provided the original authors and source are credited and other Frontiers conditions are complied with.

*Correspondence: Tetsu Ando, Graduate School of Bio-Applications and Systems Engineering, Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology, Koganei, Tokyo 184-8588, Japan. e-mail: antetsu@cc.tuat.ac.jp

Hayaki Watanabe

Hayaki Watanabe