- Institute for Immunology, University of Munich, Munich, Germany

According to the “two-step model,” the intrathymic generation of CD4+ regulatory T (Treg) cells segregates into a first, T cell receptor (TCR)-driven phase and a second, cytokine-dependent phase. The initial TCR stimulus gives rise to a CD25+Foxp3− developmental intermediate. These precursors subsequently require cytokine signaling to establish the mature CD25+Foxp3+ Treg cell phenotype. In addition, costimulation via CD28/B7 (CD80/86) axis is important for the generation of a Treg cell repertoire of normal size. Recent data suggest that CD28 or B7 deficient mice lack CD25+Foxp3− Treg cell progenitors. However, these data leave open whether costimulation is also required at subsequent stages of Treg differentiation. Also, the fate of “presumptive” Treg cells carrying a permissive TCR specificity in the absence of costimulation remains to be established. Here, we have used a previously described TCR transgenic model of agonist-driven Treg differentiation in order to address these issues. Intrathymic adoptive transfer of Treg precursors indicated that costimulation is dispensable once the intermediate CD25+Foxp3− stage has been reached. Furthermore, lack of costimulation led to the physical loss of presumptive Treg cells rather than their escape from central tolerance and differentiation into the conventional CD4+ T cell lineage. Our findings suggest that CD28 signaling does not primarily operate through enhancing the TCR signal strength in order to pass the threshold intensity required to initiate Treg cell specification. Instead, costimulation seems to deliver unique and qualitatively distinct signals that coordinately foster the developmental progression of Treg precursors and prevent their negative selection.

Introduction

CD4+ regulatory T (Treg) cells expressing the transcription factor Foxp3 exert an essential function for the maintenance of self-tolerance and immune homeostasis (Sakaguchi, 2004). There is good evidence that a substantial fraction of the Treg cell repertoire originates from the thymus; for instance, there is a large degree of sequence-overlap between the T cell receptor (TCR) repertoires of thymic and peripheral Foxp3+ cells (Hsieh et al., 2006; Pacholczyk et al., 2006; Lio and Hsieh, 2011).

Entry into the Treg cell lineage during thymocyte development is believed to depend upon instructive processes ensuing from self-antigen recognition (Wirnsberger et al., 2011). Evidence for this has been obtained in TCR/neo-self-antigen double transgenic systems (Jordan et al., 2001; Apostolou et al., 2002; Kawahata et al., 2002; Aschenbrenner et al., 2007) and also stems from observations that polyclonal thymocytes bearing superantigen-reactive TCRs are substantially enriched in Foxp3+ cells (Papiernik et al., 1998; Ribot et al., 2006). The exact parameters and modalities of antigen recognition that specify whether an autoreactive MHC II-restricted thymocyte enters the Treg lineage or is subject to negative selection remain to be established; however, there is some consensus that interactions of intermediate avidity may favor Treg cell differentiation over clonal deletion (Feuerer et al., 2007; Atibalentja et al., 2009; Picca et al., 2009; Hinterberger et al., 2010). Furthermore, co-signals provided by common γ-chain cytokines [interleukin (IL)-2 in particular, but also IL-7 and -15; Fontenot et al., 2005a; Mayack and Berg, 2006; Yao et al., 2007; Bayer et al., 2008; Vang et al., 2008] as well as costimulation through CD28/B7 interactions are required for efficient intrathymic differentiation of Treg cells.

Mice deficient in CD28 or its ligands CD80 and CD86 (B7.1 and B7.2, respectively) display a significant decrease in the number of thymic and peripheral Treg cells (Salomon et al., 2000; Tang et al., 2003; Lohr et al., 2004; Tai et al., 2005). Although costimulation has been implicated in IL-2 production (Lindstein et al., 1989; Fraser et al., 1991; Jenkins et al., 1991), the failure of Cd28−/− or Cd80/Cd86−/− mice to generate a Treg cell pool of normal size is not directly linked to cytokine deprivation. Thus, the inefficient entry of Cd28−/− thymocytes into the Treg lineage is not “rescued” by the presence of bystander Cd28+/+ cells in mixed bone marrow chimeras, indicating that the paucity of thymic Treg cells in costimulation deficient mice primarily reflects a T cell-intrinsic function of the CD28 signaling axis (Tai et al., 2005).

The “two-step model” of intrathymic Treg differentiation suggests a sub-division into an antigen-driven instruction phase and a cytokine-dependent (but largely antigen independent) consolidation phase. Accordingly, CD25+Foxp3− CD4 single-positive (SP) cells represent TCR-instructed, Treg lineage committed intermediates that require continual cytokine (IL-2, IL-7, or IL-15) signaling, but are largely independent of TCR stimulation, for their differentiation into “mature” CD25+Foxp3+ Treg cells (Burchill et al., 2008; Lio and Hsieh, 2008). Recent data support the idea that CD28 costimulation and common γ-chain cytokine signaling operate at distinct stages of intrathymic Treg differentiation. Specifically, polyclonal CD25+Foxp3− cells, which are believed to contain Treg precursors that arise through TCR-mediated instruction (“step one”) are strongly diminished in the thymus of Cd28−/− mice (Lio et al., 2010; Vang et al., 2010).

The principle requirement for costimulation during intrathymic generation of the Treg cell pool has been well documented in polyclonal systems. However, assessing the number of Foxp3+ cells in a diverse TCR repertoire does not reveal insights into the “alternative” fate of presumptive Treg cells in the absence of costimulation. Thus, it is as yet unclear whether the respective TCR specificities are physically lost from the repertoire, i.e., negatively selected, or whether these cells instead escape from central tolerance induction and enter the pool of mainstream CD4 T cells. To address this issue, we have made use of a previously described TCR transgenic model of agonist antigen-driven Treg differentiation.

Materials and Methods

Mice

T cell receptor–hemagglutinin (HA; Kirberg et al., 1994) and AIRE–HA (Aschenbrenner et al., 2007) have been described previously. Foxp3gfp reporter mice (Fontenot et al., 2005b) were kindly provided by A. Rudensky (Memorial Sloan Kettering Institute, New York). Cd28−/− (Shahinian et al., 1993), CD80/86−/−, CD80−/−, and CD86−/− mice (Borriello et al., 1997) were purchased from Jackson Laboratories. BALB/c mice were purchased from Charles River. Mice were maintained in individually ventilated cages. Animal studies were approved by local authorities (Regierung von Oberbayern, 55.2.1.54.2531-7-08).

Intrathymic Transfer

About 5 × 105 CD4 SP thymocytes or 4 × 105 cells of sorted subpopulations from TCR–HA × AIRE–HA donors (CD45.1) were injected in 3 μl PBS into one thymic lobe of CD45.2 recipients of the indicated genotype. The analysis of injected thymi was carried out by depletion of CD8+ cells, staining for the indicated surface markers and analysis of the entire thymus by flow cytometry.

Antibodies and Flow Cytometry

Phycoerythrin-conjugated annexin-V, phycoerythrin-conjugated monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) to GITR (DTA-1) and PD-1 (J43), cychrome-conjugated mAb to CD8 (53-6.7), phycoerythrin-indotricarbocyanine-conjugated mAb to CD25 (PC61), allophycocyanin-conjugated mAb to CD45.1 (A20), allophycocyanin-conjugated mAb to BrdU (Cat. No. 51-23619L), and allophycocyanin indotricarbocyanine-conjugated mAb to CD4 (GK1.5) were obtained from Becton Dickinson. Phycoerythrin-conjugated mAb to Foxp3 (FJK-16s) was from eBiosciences. The mAb to the TCR–HA was purified from hybridoma (6.5) supernatants and conjugated to phycoerythrin or Alexa Fluor 647 in our lab.

BrdU Labeling

One milligram of BrdU (Becton Dickinson) in 200 μl PBS was intraperitoneally injected into recipient mice. 24 h after injection mice were sacrificed and thymocytes were stained with the indicated surface markers. Subsequently cells were fixed, permeabilized, treated with DNase I, and stained with a mAb specific to BrdU according to the manufacturers protocol (BrdU Flow Kit, Becton Dickinson).

Bone Marrow Chimeras

Bone marrow was depleted of T cells with biotinylated mAbs to CD8 and CD4 followed by depletion with streptavidin MACS beads (Miltenyi Biotec) according to standard procedures. BALB/c recipient mice were irradiated with two split doses of 450 rad and were reconstituted with 8 × 106 bone marrow cells.

Purification of CD4 SP Cells or Treg Precursors

CD4 SP cells or subpopulations of CD4 SP cells (Treg precursors) were purified by CD8 depletion, staining for the indicated surface markers, and sorting with a FACSAria cell sorter (Becton Dickinson).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance was assessed by the two-tailed Student’s t-test with unequal variance.

Results

Loss of Presumptive Treg Cells in the Absence of Costimulation

Studies in polyclonal systems have clearly indicated a substantial reduction in the thymic production of Treg cells in the absence of costimulation (Bour-Jordan et al., 2011). However, these analyses did not reveal the fate of presumptive Treg cells under these circumstances, that is, whether the respective TCR specificities are physically lost from the repertoire or instead enter the naïve pool of CD4 T cells. To address this issue, we used TCR–HA × AIRE–HA double transgenic mice. In these animals, expression and presentation of cognate antigen by medullary thymic epithelial cells (mTECs) promotes the negative selection of the majority of influenza HA specific CD4 SP thymocytes, while at the same time a distinct and traceable cohort of HA-specific CD4 SP cells differentiate into Treg cells (Aschenbrenner et al., 2007; Hinterberger et al., 2010). T cells expressing the HA-specific TCR (TCR–HA) can conveniently be traced using the anticlonotypic antibody 6.5.

In the absence of cognate antigen, about 30% of CD4 SP cells express the HA-specific TCR–HA (Figure 1A). Expectedly, in TCR–HA single-transgenic mice, the fraction of TCR–HA+ CD4 SP thymocytes was indistinguishable irrespective of whether costimulation was provided or not (data not shown). By contrast, when TCR–HA × AIRE–HA mice were bred onto a CD28 or CD80/CD86 deficient background, we observed a significantly altered thymic phenotype. Specifically, there was a substantially decreased frequency of TCR–HA+ cells among CD4 SP thymocytes when compared to costimulation competent TCR–HA × AIRE–HA controls (Figure 1A). These somewhat surprising initial findings indicated that lack of costimulation augmented the antigen-driven loss of HA-specific CD4 SP cells.

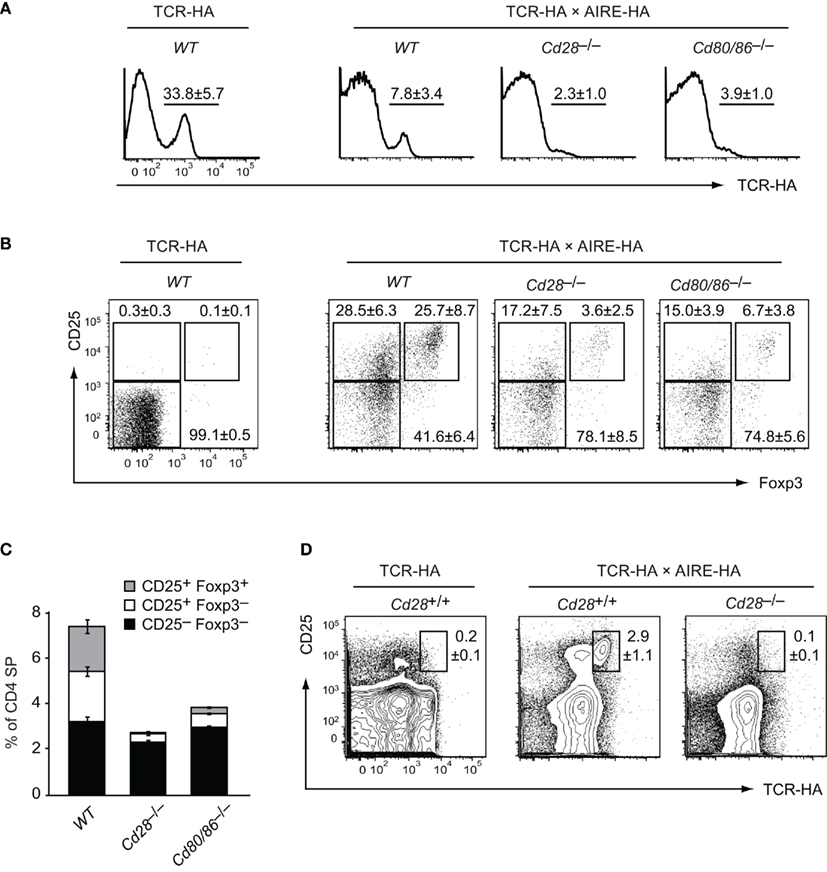

Figure 1. Loss of HA-specific thymic Treg precursor cells in costimulation deficient mice. Thymocytes from 6-week-old TCR–HA single-transgenic mice and TCR–HA × AIRE–HA mice on a costimulation sufficient (=WT), Cd28−/− or Cd80/86−/− background were stained for CD4, CD8, TCR–HA, CD25, and Foxp3 (n = 5 for TCR–HA, n = 36 for WT TCR–HA × AIRE–HA, n = 14 for Cd28−(−/ TCR–HA × AIRE–HA, n = 13 for Cd80/86−/− TCR–HA × AIRE–HA). (A) Frequency of TCR–HA+ cells (±SD) among CD4 SP cells (P = 3 × 10−11 for WT vs. Cd28−/− and P = 2 × 10−7 for WT vs. Cd80/Cd86−/−). (B) Expression of CD25 and Foxp3 by gated TCR–HA+ CD4 SP thymocytes. (C) Relative abundance (±SD) of TCR–HA positive CD25–Foxp3− and CD25+Foxp3− Treg precursor subpopulations and mature CD25+Foxp3+ Treg cells among gated CD4 SP thymocytes (CD25−Foxp3− subsets: P = 0.0002 for WT vs. Cd28−/− and P = 0.3 for WT vs. Cd80/Cd86−/−; CD25+Foxp3− subsets: P = 5 × 10−12 for WT vs. Cd28−/− and P = 1 × 10−10 for WT vs. Cd80/Cd86−/−; CD25+Foxp3+ subsets: P = 3 × 10−16 for WT vs. Cd28−/−; and P = 4 × 10–15 for WT vs. Cd80/Cd86−/−). The relative and absolute abundance of CD4 SP thymocytes was not significantly different between the various genotypes (data not shown). (D) Expression of CD25 and TCR–HA by gated CD4+ T cells from peripheral lymph nodes of the indicated genotype.

Among TCR–HA+ CD4 SP thymocytes of costimulation sufficient TCR–HA × AIRE–HA mice, we found that CD25−Foxp3−, CD25+Foxp3−, and CD25+ Foxp3+ cells are represented at roughly equal proportions (Figure 1B, and Wirnsberger et al., 2009). Consistent with the “two-step” model of Treg cell development (Lio and Hsieh, 2008), we have shown previously that these subsets represent consecutive stages of agonist induced Treg cell development (CD25−Foxp3− → CD25+Foxp3− → CD25+Foxp3+; Wirnsberger et al., 2009). In the absence of CD28 or CD80/CD86 costimulation, the percentage of “mature” CD25+Foxp3+ Treg cells among TCR–HA+ CD4 SP thymocytes and their immediate CD25+Foxp3− precursors was considerably decreased (Figures 1B,C). Instead, the majority of residual TCR–HA+ CD4 SP cells were CD25−Foxp3−, suggesting a developmental bottleneck at the transition from a CD25−Foxp3− to a CD25+Foxp3− phenotype, i.e., at the TCR-driven “step one” of Treg cell differentiation.

The CD25−Foxp3− surface phenotype of the majority of TCR–HA+ CD4 SP cells in costimulation deficient mice might have indicated that these cells are naive cells that have not received a “Treg instructing” TCR signal of appropriate strength. Potentially, such cells might escape from central tolerance induction and seed peripheral lymphoid organs. If this were the case, one might expect to find TCR–HA+ non-Treg CD4+ T cells in the periphery of costimulation deficient TCR–HA × AIRE–HA mice. However, inspection of peripheral CD4 T cell compartments revealed the complete absence of TCR–HA+ cells in costimulation deficient mice (Figure 1D). Specifically, not only was the distinct population of TCR–HA+ CD25+ Treg cells that is seen in costimulation sufficient mice absent, but there was also no discernible emergence of TCR–HA+ CD25− cells in peripheral lymphoid organs (Figure 1D).

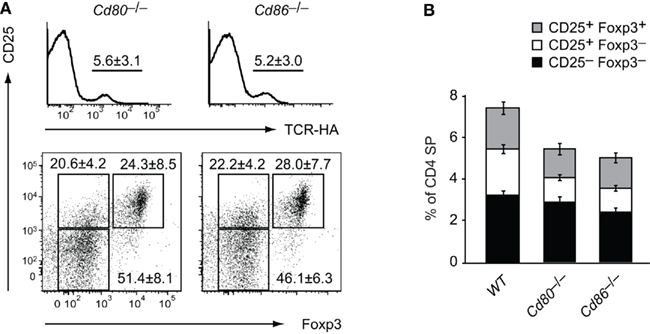

In order to address in how far either CD80 or CD86 provided the essential signals for Treg cell differentiation, we bred the TCR–HA × AIRE–HA system onto the respective single knock-out background. This revealed a degree of redundancy of the two B7 family members in that both Cd80−/− and Cd86−/− mice only showed a relatively mild reduction of CD25+Foxp3− precursors and their “mature” CD25+Foxp3+ progeny among TCR–HA+ CD4 SP thymocytes (Figures 2A,B).

Figure 2. Partially redundant role of CD80 and CD86 for intrathymic Treg development. Thymocytes from 6-week-old TCR–HA × AIRE–HA mice on a Cd80−/− (n = 14) or Cd86−/− (n = 20) background were stained for CD4, CD8, TCR–HA, CD25, and Foxp3. (A) Frequency of TCR–HA+ cells (±SD) among CD4 SP cells (P = 0.09 for WT vs. Cd80−/− and P = 0.03 for WT vs. Cd86−/−; upper panel). The lower panel depicts the expression of CD25 and Foxp3 by gated TCR–HA+ CD4 SP thymocytes. (B) Relative abundance (±SD) of TCR–HA positive CD25−Foxp3− and CD25+Foxp3− Treg precursor subpopulations and mature CD25+Foxp3+ Treg cells among gated CD4 SP thymocytes (CD25–Foxp3− subsets: P = 0.8 for WT vs. Cd80−/− and P = 0.4 for WT vs. Cd86−/−; CD25+Foxp3− subsets: P = 0.003 for WT vs. Cd80−/− and P = 0.0002 for WT vs. Cd86−/−; CD25+Foxp3+ subsets: P = 0.08 for WT vs. Cd80−/− and P = 0.06 for WT vs. Cd80/Cd86−/−).

In sum, these observations are consistent with a role of costimulation in the TCR-driven development of early intermediates of thymic Treg development. A similar conclusion has recently been drawn from the absence of CD25+GITR+CD122+ cells among polyclonal CD4 SP cells of Cd28−/− mice (Lio et al., 2010; Vang et al., 2010). Importantly, our data suggest that lack of costimulation, rather than allowing these presumptive Treg cells to escape from clonal deviation and to enter the naïve repertoire, leads to physical loss of the respective specificities. In other words, under conditions that are otherwise permissive for Treg cell differentiation (i.e., appropriate strength of TCR stimulus), lack of costimulation results in the conversion of Treg differentiation into negative selection.

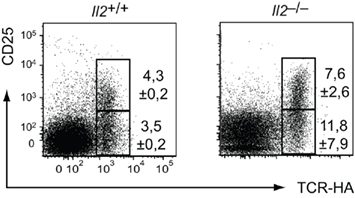

The Function of Costimulation Extends beyond IL-2 Signaling and is Cell-Intrinsic

CD28 costimulation has been implicated in IL-2 production (Lindstein et al., 1989; Fraser et al., 1991; Jenkins et al., 1991). Hence, its abrogation may impinge on Treg cell differentiation through lack of IL-2 mediated cell extrinsic survival and/or differentiation signals that orchestrate the cytokine-dependent “second” phase of Treg cell differentiation (Burchill et al., 2008; Lio and Hsieh, 2008; Wirnsberger et al., 2009). However, upon breeding onto an Il2−/− background, thymi of TCR–HA × AIRE–HA mice – in contrast to what was observed in Cd28−/− or Cd80/86−/− mice – did not show a reduction of TCR–HA+ CD4 SP cells and of mature CD25+ cells within this population (Figure 3). This is consistent with earlier observations that IL-2 acts on thymic Treg cell differentiation in an at least partly redundant manner with other common γ-chain cytokines such IL-7 or IL-15 (D’Cruz and Klein, 2005; Fontenot et al., 2005a; Vang et al., 2008) and indicates that the apparent developmental blockade and loss of TCR–HA+ Treg cells in CD28 or CD80/86 deficient TCR–HA × AIRE–HA mice cannot be explained by an eventual requirement of CD28/B7 costimulation solely for IL-2 production.

Figure 3. Efficient intrathymic Treg differentiation in IL-2 deficient TCR–HA × AIRE–HA mice. Thymocytes from 3-week-old TCR–HA × AIRE–HA mice on an Il2+/+ (n = 3) or Il2–/– (n = 3) background were stained for CD4, CD8, TCR–HA, CD25, and Foxp3. Numbers indicate the average frequency (±SD) of cells within gates.

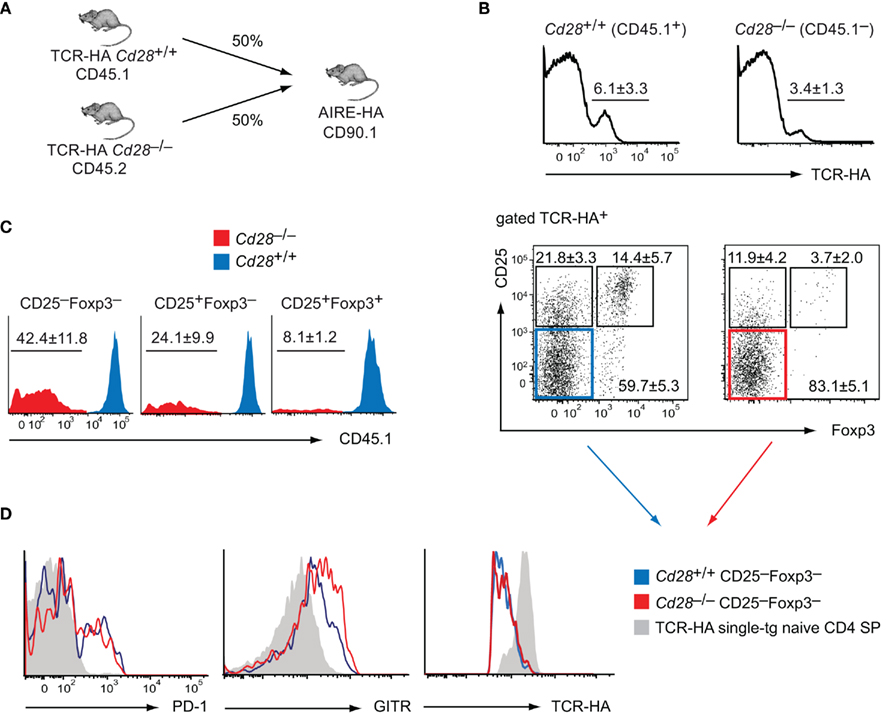

In order to test whether the requirement for costimulation was cell-intrinsic, we generated mixed bone marrow chimeras. Irradiated AIRE–HA mice or wild-type controls were reconstituted with a 1/1 mixture of TCR–HA transgenic Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/− bone marrow cells (Figure 3). As expected, in the absence of cognate antigen, Cd28+/+, and Cd28−/− cells equally contributed to all thymocyte subsets (not shown). In the presence of cognate antigen, TCR–HA+ cells represented about 6% of Cd28+/+ cells among CD4 SP thymocytes and segregated into CD25−Foxp3−, CD25+Foxp3−, and CD25+Foxp3+ subsets similar to what was observed in TCR–HA × AIRE–HA mice (Figure 4B; compare Figures 1A,B). By contrast, TCR–HA+ cells made up for only about 3% of Cd28−/− cells among CD4 SP cells, and the majority of these cells had a CD25−Foxp3− phenotype (Figure 4B). Overall, the contribution of Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/− cells to CD25−Foxp3− TCR–HA+ thymocytes reflected the 1/1 input ratio, whereas Cd28−/− cells were strongly underrepresented among the subsequent CD25+Foxp3− “intermediate” population and were barely detectable within the “mature” CD25+Foxp3+ subset (Figure 4C).

Figure 4. Cell-intrinsic function of CD28 in intrathymic Treg development. (A) Experimental strategy to generate mixed bone marrow (bm) chimeras. Specifically, 4 × 106Cd28+/+ TCR–HA bm cells (CD45.1) and 4 × 106Cd28–/– TCR–HA bm cells (CD45.2) were i.v. injected into irradiated AIRE–HA recipients (n = 9). Six weeks after bm-reconstitution, CD8 depleted thymocytes were stained for CD4, TCR–HA, CD25, CD45.1, CD45.2, and Foxp3. (B) Frequency of TCR–HA+ cells (±SD) among Cd28+/+ (CD45.1+) and Cd28−/− (CD45.1−) CD4 SP cells (upper panel; P = 0.04). The lower panel depicts the expression of CD25 and Foxp3 by gated Cd28+/+ (CD45.1+) or Cd28−/− (CD45.1−) TCR–HA+ CD4 SP thymocytes. (C) Relative abundance of Cd28+/+ (CD45.1+; depicted in blue) vs. Cd28−/− (CD45.1−; depicted in red) cells among CD25−Foxp3− and CD25+Foxp3− Treg precursor subpopulations or mature CD25+Foxp3+ Treg cells, gated on all TCR–HA+ CD4 SP thymocytes. Numbers indicate the average frequency (±SD) of cells within gates. (D) Sub-fractions of cells were also stained for PD-1 or GITR. The expression of PD-1 or GITR as well as TCR–HA on gated CD25−Foxp3−TCR–HA+ CD4 SP thymocytes of Cd28+/+ (blue histogram) or Cd28−/− (red histogram) origin was assessed. The gray histogram indicates the expression of the respective markers on “naïve” CD25−Foxp3−TCR–HA+ CD4 SP thymocytes from TCR–HA single-transgenic animals.

Together, these findings clearly indicated that costimulation sufficient bystander cells do not rescue the progression of CD28 deficient cells toward a mature Treg cell phenotype, for instance through provision of IL-2 or other factors in trans. Instead, there is a cell-intrinsic requirement for CD28 signaling at the earliest stages of Treg cell differentiation that is unrelated to the presumed role of IL-2 at a subsequent stage of this process.

CD28 Deficient HA-Specific CD25−Foxp3− Cells are Not Naive

Our results so far revealed that in the presence of cognate antigen, HA–specific CD4 SP cells with a CD25−Foxp3− phenotype could be found in similar proportions irrespective of whether or not CD28/B7 costimulation was available, whereas CD25+Foxp3−and CD25+Foxp3+ cells were strongly reduced in the absence of costimulation. This suggested a developmental blockade at the transition to a CD25+Foxp3− phenotype, i.e., at “step one” of Treg cell differentiation. Alternatively, it was possible that CD25−Foxp3− CD4 SP cells only in a costimulation sufficient environment represented a true Treg intermediate downstream of the initiating TCR stimulus, whereas in the absence of costimulation, CD25−Foxp3− CD4 SP cells may instead actually be naïve cells.

In order to distinguish these two possibilities, we performed a more detailed surface marker analysis of Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/− CD25−Foxp3− CD4 SP thymocytes in the mixed bone marrow chimeras depicted in Figure 4A and compared their phenotype to bona fide “naïve” CD25–Foxp3– CD4 SP thymocytes from TCR–HA single-transgenic mice (Figure 4D). Both Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/− CD25−Foxp3− CD4 SP thymocytes displayed a similar up-regulation of the surface molecules PD-1 and GITR, whereas truly naïve CD4 SP cells were PD-1 negative and GITRlow. In further support that Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/− CD25−Foxp3− CD4 SP thymocytes had received a similar TCR stimulus, expression of the TCR was similarly down-regulated on either population, presumably as a result of cognate antigen encounter (Figure 4D).

In sum, these findings provided further evidence that in the absence of costimulation, HA-specific cells do not escape as naïve T cells. Instead, our observations support the idea that irrespective of whether or not costimulation is provided, TCR–HA+ progenitors receive a TCR signal that is sufficient to mediate the acquisition of an “early” Treg progenitor phenotype. However, in the absence of CD28 signals, these cells only very inefficiently progress toward the subsequent CD25+Foxp3− stage and the mature CD25+Foxp3+ Treg phenotype.

Costimulation Does Not Act via Oroliferative Expansion of Treg Cell Precursors

So far, we have considered that in the absence of costimulation, the earliest phase of Treg differentiation represents a developmental dead end. An alternative explanation for the paucity of CD25+Foxp3− cells and their CD25+Foxp3+ progeny in CD28 or CD80/86 deficient mice would be that costimulation would orchestrate the entry of Treg cell precursors into cell cycling, thereby mediating the proliferative expansion of intermediate Treg precursors rather than their actual developmental progression. Of note, despite a certain consensus that cycling of “mature” Foxp3+ thymocytes is barely detectable, it is as yet unclear whether Treg cell differentiation involves an early expansion phase prior to Foxp3 expression. This is particularly relevant for the earliest CD25−Foxp3− progenitor stage, because in a polyclonal repertoire these early Treg precursors are essentially impossible to distinguish from the bulk of “naïve” non-Treg cell precursors.

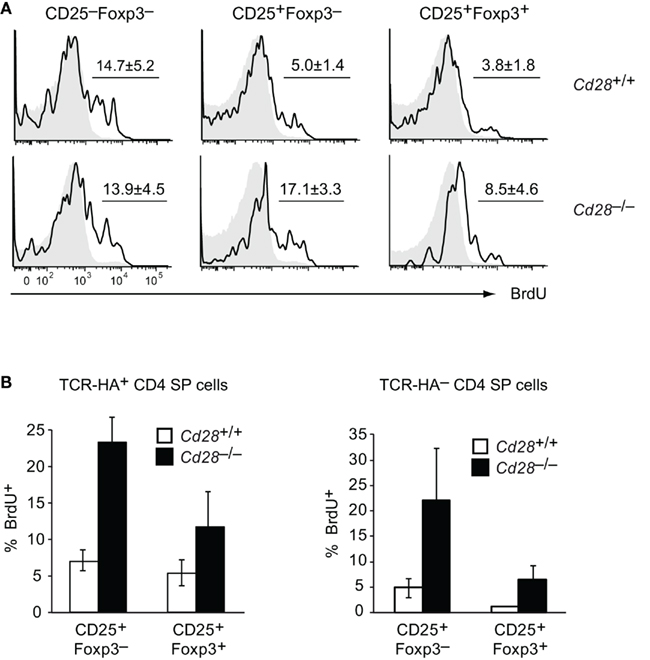

In order to address this question, we performed BrdU labeling experiments. 24 h after a single injection of BrdU into Cd28+/+ TCR–HA × AIRE–HA mice, a substantial fraction of TCR–HA+ CD25−Foxp3− cells and to a lesser extent also of CD25+Foxp3− “intermediate” precursors had incorporated BrdU, whereas BrdU+ cells were very rare among mature Foxp3+ cells (Figure 5A). In the absence of costimulation (in Cd28−/− TCR–HA × AIRE–HA mice), TCR–HA+ CD25−Foxp3− cells incorporated similar amounts of BrdU when compared to their counterparts in Cd28+/+ mice, indicating that entry into the cell cycle of this early Treg cell precursor-population is independent of CD28/B7-mediated costimulatory signals (Figure 5A). Somewhat surprisingly, the incorporation of BrdU by CD25+Foxp3– cells and also by “mature” CD25+Foxp3+ thymocytes was even increased rather than diminished in the absence of CD28 co-signals (Figures 5A,B).

Figure 5. Proliferation of TCR–HA+ Treg precursors is not reduced in the absence of CD28 and recapitulates the behavior of thymocytes expressing diverse TCRs. 24 h after a single injection of BrdU, thymocytes from TCR–HA × AIRE–HA mice on a Cd28+/+ (n = 4) or Cd28−/− (n = 7) background were stained for CD4, CD8, TCR–HA, CD25, Foxp3, and BrdU incorporation. (A) Extent of BrdU incorporation (black open histogram) by gated TCR–HA+ CD4 SP Treg precursors (CD25−Foxp3− or CD25+Foxp3−) or mature TCR–HA+ CD4 SP Treg cells (CD25+Foxp3+) in Cd28+/+ (upper panels) or Cd28−/− (lower panels) mice. Isotype control staining of the respective samples are shown as histogram overlay (gray filled; P = 0.8 for CD25–Foxp3− subsets; P = 2 × 10−4 for CD25+Foxp3− subsets; P = 0.04 for CD25+Foxp3+ subsets) (B) Comparison of BrdU incorporation by Cd28+/+ (white bars) or Cd28−/− (black bars) CD25+Foxp3− or CD25+Foxp3+ CD4 SP thymocytes that either express the transgenic TCR–HA (left panel) or express endogenously rearranged TCRs (TCR–HA−, right panel).

In order to address whether these observations similarly applied to non-transgenic polyclonal TCR specificities, we also compared the BrdU incorporation by TCR–HA− CD4 SP thymocytes of Cd28+/+ and Cd28−/− TCR–HA × AIRE–HA mice. These cells express endogenously rearranged TCRs, and their eventual entry into the Treg lineage reflects polyclonal Treg development. Indeed, a clear tendency toward more proliferation in the absence of costimulation was also observed for CD25+Foxp3− and “mature” CD25+Foxp3+ cells among TCR–HA− CD4 SP thymocytes, emphasizing that our observations for TCR transgenic Treg cells and their precursors faithfully recapitulated the behavior of polyclonal T cells (Figure 5B).

Taken together, our findings suggest that the early specification into the Treg cell lineage indeed coincides with entry of “pre-Foxp3” Treg precursors into cell cycling. However, our data strongly argue against a requirement for CD28/B7 costimulation for proliferative expansion of a minute “TCR-primed” precursor-population.

The TCR-Driven Instructive But Not the Cytokine-Dependent Consolidation Phase of Treg Differentiation Requires Costimulation

A precise assessment of where and when costimulation is required during intrathymic Treg cell development is difficult to achieve when studying steady state thymocyte differentiation. For instance, it is possible that the requirement for costimulation even precedes the TCR stimulus, whereby costimulation may somehow prime cells for a subsequent instructive signal. Similarly, an early bottleneck in Treg differentiation may mask a continual requirement for costimulation also at a subsequent stage of Treg differentiation.

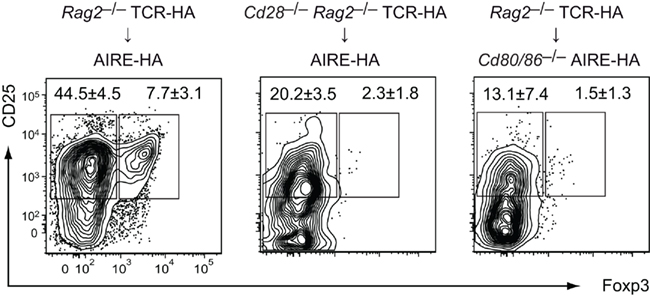

Our observations so far did not reveal whether the costimulatory interactions that support Treg differentiation occur before the CD4 SP T cell stage, for instance concomitant to positive selection. We have shown previously that Treg differentiation in the TCR–HA × AIRE–HA thymus can be dissociated from positive selection and CD4 lineage commitment. Specifically, injection of CD4 SP cells from TCR–HA Rag2−/− mice, i.e., truly naïve, monoclonal cells that did not contain any pre-existing Foxp3+ cells, into AIRE–HA thymi resulted in a substantial fraction of cells entering the CD25+Foxp3+ Treg cell lineage (Wirnsberger et al., 2009; see also Figure 6). These finding indicated that self-antigen-driven intrathymic Treg differentiation can be initiated in the absence of “nominal” antigen encounter prior to the CD4 SP stage.

Figure 6. Costimulation is required simultaneous to or in close temporal proximity to the Treg lineage-instructing TCR stimulus at the CD4 SP stage. 5 × 105 CD4 SP cells from TCR–HA Foxp3gfp transgenic animals on a Rag2−/− background (CD45.1) were intrathymically injected into Cd80/86+/+ (left) or Cd80/86−/− AIRE–HA (right) recipients (CD45.2). In a “reciprocal” setting, we injected CD4 SP cells from Cd28−/− TCR–HA Foxp3gfpRag2−/− mice into the thymus of costimulation sufficient (Cd80/86+/+) AIRE–HA recipients (middle). 6 days after transfer, injected cells were analyzed for CD25 and Foxp3 expression. Numbers indicate the average frequency (±SD) of cells within gates (n = 4 for all groups).

In order to dissociate positive selection in the absence or presence of CD28/B7 costimulatory interactions from cognate antigen encounter at the CD4 SP stage in the absence or presence of costimulation, we intrathymically (i.t.) injected CD28 deficient Rag2−/− TCR–HA SP thymocytes into AIRE–HA recipients. In a “reciprocal” setting, we injected Rag2−/− TCR–HA SP cells from costimulation sufficient animals into Cd80/86−/− recipients (Figure 6). Both sets of experiments yielded essentially identical outcomes, namely an almost complete absence of Treg differentiation, suggesting that costimulation is necessary concomitant to or immediately subsequent to the instructing TCR stimulus (Figure 6).

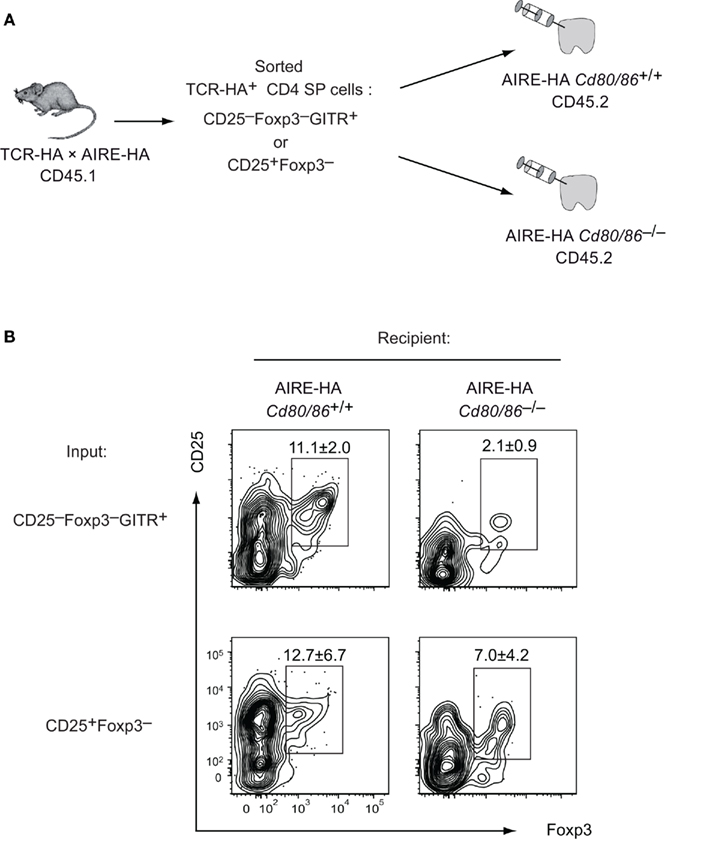

Our data so far revealed an essential requirement for costimulation simultaneous to or in close temporal proximity to the instructing TCR stimulus. When analyzing steady state Treg cell development in the absence of costimulation, the early developmental arrest at the CD25−Foxp3− stage precludes the analysis of an eventually continual requirement for CD28/B7 interactions at subsequent stages of Treg differentiation. In order to address this issue, we isolated CD25−Foxp3−GITR+ cells (i.e., the earliest distinct subset of TCR-triggered Treg cell precursors) and cells at the subsequent CD25+Foxp3− intermediate stage (i.e., cells that require common γ-chain cytokines – but not TCR stimulation – to mature into CD25+Foxp3+ cells) from costimulation sufficient TCR–HA × AIRE–HA mice and injected them into Cd80/86–/– recipient thymi (Figure 7A). This revealed that CD25–Foxp3–GITR+ input cells were strongly dependent upon persistent costimulation to progress toward a mature Treg phenotype, whereas CD25+Foxp3− cells gave rise to mature Treg cells irrespective of whether or not continual costimulation was provided in the host microenvironment (although Treg occurred perhaps slightly less efficient in Cd80/86−/− recipients; Figure 7B). Taken together, these data support a model whereby B7/CD28 costimulation is tightly linked to the TCR-driven first phase of Treg differentiation, but is dispensable at the cytokine-dependent second phase.

Figure 7. The TCR-driven instructive but not the cytokine-dependent consolidation phase of Treg differentiation requires costimulation. (A) Experimental design: TCR–HA+ Treg precursor subsets (CD25−Foxp3−GITR+ and CD25+Foxp3−) were isolated from CD4 SP thymocytes of TCR–HA × AIRE–HA animals (CD45.1). 4 × 105 cells were i.t. injected into Cd80/86+/+ or Cd80/−/−AIRE–HA recipients (CD45.2). (B) Four days after injection transferred cells were analyzed for CD25 and Foxp3 expression. Numbers indicate the average frequency (±SD) of cells within gates (n = 3 for transfer of CD25−Foxp3−GITR+ cells and n = 5 for transfer of CD25+Foxp3− cells; P = 0.0065 for CD25−Foxp3−GITR+ input cells and P = 0.15 for CD25+Foxp3−input cells).

Discussion

Our findings suggest that the critical function of B7/CD28 costimulation is to support the development and survival of the CD25+Foxp3− intermediate stage of Treg differentiation. Furthermore, using adoptive transfer of Treg precursors, we could show that costimulation is largely dispensable once the CD25+Foxp3− intermediate stage of Treg differentiation has been reached. Hence, the B7 co-stimulus is mainly required simultaneous to or in close temporal proximity to the instructive TCR signal, i.e., at “step one” of Treg differentiation. These findings are consistent with two recent reports indicating that there is a substantial diminution of polyclonal CD25+Foxp3− Treg precursor cells in CD28 deficient mice (Lio et al., 2010; Vang et al., 2010). Importantly, these analyses of polyclonal Treg development did not identify the actual fate of “presumptive” Treg cells in the absence of B7/CD28 costimulation. Here, the use of a TCR transgenic model of cognate antigen-driven Treg differentiation allowed us to reveal that lack of costimulation leads to the physical loss of Treg precursors from the T cell repertoire. As a net effect, it thus appears that CD28 signaling protects Treg precursors from clonal deletion and thereby promotes the emergence of a Treg repertoire of normal size.

Our findings have obvious implications for the observation that autoimmune prone NOD mice on a CD28 or B7 deficient background develop a more severe and accelerated form of diabetes (Salomon et al., 2000). Thus, it appears that the aggressive form of diabetes in this setting is caused by a deficiency in Treg cells rather than by escape of otherwise “vetoed” T cells specificities from central tolerance. Consistent with this, adoptive transfer of polyclonal or islet antigen specific Treg cells prevented diabetes in NOD Cd28−/− mice (Salomon et al., 2000; Tang et al., 2004).

The avidity model of Treg differentiation posits that Treg differentiation ensues from cognate antigen interactions whose strength lies in between the signaling intensity required for positive selection on the one hand and clonal deletion on the other hand (Feuerer et al., 2007; Atibalentja et al., 2009; Picca et al., 2009; Simons et al., 2010). We have recently obtained further evidence for this hypothesis by attenuating antigen presentation in the TCR–HA × AIRE–HA model through “designer micro-RNA” mediated knock-down of MHC class II on mTECs. This resulted in a diminished extent of negative selection and an increased emergence of Treg cells, which is consistent with the notion that intermediate avidity-interactions favor Treg differentiation over negative selection (Hinterberger et al., 2010). Considering the predictions of the avidity hypothesis, one may have expected TCR–HA+ cells to escape from negative selection and Treg induction and to eventually enter the naïve CD4 T cell pool, if B7/CD28 costimulation merely were to amplify the strength of an integrated signal downstream of the TCR and CD28. However, this is clearly not the case. Instead, lack of costimulation increases the antigen-driven net loss of TCR–HA+ cells. Hence, our findings indicate that CD28 signaling does not operate primarily through amplifying the TCR signal, but through qualitatively changing the interpretation of the TCR signal and thereby initiating a distinct genetic program. Consistent with this, we found that in the presence of the AIRE–HA transgene, TCR–HA+ CD25−Foxp3−cells displayed identical signs of early activation (up-regulation of PD-1 and GITR and down-regulation of the TCR) irrespective of whether they were Cd28+/+ or Cd28−/−. Parallel signals emanating from CD28/B7 costimulation may then support the progression toward the cytokine-dependent “step two” of Treg differentiation. It remains possible that the early events associated with entry into the Treg lineage can even be set off by a TCR signal of matching strength independent of costimulation.

Generally, CD28 co-signals are thought to stabilize mRNAs and amplify the activation of nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) and nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), thereby supporting T cell cytokine production, proliferation, survival, and differentiation (Rudd et al., 2009). Concerning a potential role of CD28 signaling in cytokine production, it is hard to see how this should account for the block of thymic Treg development at “step one,” which is believed to be TCR-driven but cytokine independent. Along these lines, we and others found that the bottleneck in Treg development caused by CD28 deficiency affects a stage of Treg differentiation considerably upstream of the perturbations that are caused by IL-2 deficiency (Bayer et al., 2005; D’Cruz and Klein, 2005; Fontenot et al., 2005a; Setoguchi et al., 2005; Vang et al., 2008). As already discussed above, it also appears highly unlikely that CD28 functions to merely amplify the TCR signal. Sequence analyzes of polyclonal Treg cells generated in the absence or presence of costimulation also argue against this scenario (Lio et al., 2010). Thus, it was found that the residual Treg cell repertoire generated in the absence of CD28 was not dramatically altered at the level of TCR specificities. Instead, the relative abundance of individual TCR specificities within the contracted Treg pool of Cd28−/− mice resembled that of the WT Treg repertoire, at least with regard to abundant specificities (Lio et al., 2010). On this basis, it was suggested that CD28 signaling provides signals (parallel to TCR stimulation) that facilitate Treg development, but by themselves are not truly essential (Lio et al., 2010).

An alternative explanation why the polyclonal Treg compartment is reduced by about 80% in Cd28−/− mice would be that some, but not other TCRs depend upon CD28 co-signals to segregate into the Treg compartment. However, our observations in a TCR transgenic system are more consistent with the “facilitator” scenario, as the differentiation of quasi-monoclonal TCR–HA+ Treg cells is diminished by a factor of about five-fold rather than being fully abolished (or not being affected at all).

In order to explain why the defect in CD28 or B7 deficient mice is quantitative rather than qualitative, we considered the hypothesis that costimulation might foster Treg generation through promoting the proliferative expansion of Treg precursors rather than actually instructing their differentiation per se. However, we could not find any evidence that this was the case. In fact, the proliferation of Treg precursors was even increased in the absence of costimulation, perhaps suggesting a compensatory mechanism. On the basis of this finding, the most plausible scenario is that CD28 signaling serves a dual, partly instructive (as bona fide differentiation factor) and partly permissive (as survival factor) function during Treg differentiation. Of note, neither function appears to be truly essential, so that the role of costimulation is indeed perhaps better described as that of a “catalyst.”

The full spectrum of molecular events downstream of CD28 signaling during Treg differentiation remains to be established. However, recent work has shed light on how costimulation may support the differentiation of Treg precursors through qualitatively modulating signaling events downstream of the TCR. CD28 communicates with several downstream signaling cascades through distinct motifs in its cytoplasmic tail that mediate interactions with Lck and the PI3K pathway, respectively. Several groups have reported that efficient Treg cell generation does not require CD28’s PI3K-binding motif, whereas the Lck-interacting P187YAPP motif seems to be crucial for Treg differentiation (Tai et al., 2005; Lio et al., 2010; Vang et al., 2010). Mutations in the CD28 P187YAPP motif strongly diminish TCR/CD28 mediated NF-κB activation (Sanchez-Lockhart et al., 2008), and the ablation of genes involved in NF-κB activation (PKC-θ, CARMA-1, Bcl-10, IKK-2) impairs thymic Treg differentiation (Schmidt-Supprian et al., 2004; Barnes et al., 2009; Medoff et al., 2009). The recent identification of c-Rel as essential NF-κB family transcription factor in Treg differentiation may provide important clues as to how integrated TCR/CD28 signaling activates the transcriptional program that controls Treg differentiation (Isomura et al., 2009; Long et al., 2009; Ruan et al., 2009; Deenick et al., 2010; Visekruna et al., 2010). One aspect of c-Rel’s function seems to be direct control of the Foxp3 gene through binding to a DNA motif resembling the CD28-response element in the IL-2 gene (Zheng et al., 2010). It has been suggested that through opening and remodeling of the Foxp3 locus, c-Rel activation downstream of TCR/CD28 signaling may serve a bona fide lineage instructing function (Josefowicz and Rudensky, 2009). However, considering that Treg differentiation can proceed surprisingly well in the absence of a functional Foxp3 gene (Gavin et al., 2007; Hill et al., 2007; Lin et al., 2007; Lahl et al., 2009), it appears reasonable to assume that NF-κB-signaling or other signaling pathways downstream of CD28 also initiate further – as yet unknown – instructive molecular events not related to Foxp3-induction. At the same time, it is likely that CD28 signaling in parallel elicits a transcriptional program that is of rather permissive nature. It may thereby set the stage for “step two” of intrathymic Treg differentiation, for instance by up-regulating components of the IL-2 receptor (Lio et al., 2010; Vang et al., 2010). Unraveling these functions will be challenging, since the presumed lineage instructing function of IL-2 signaling in Treg cells is, on the one hand, not absolute and, on the other hand, inextricably intertwined with its pro-survival function (Malek et al., 2002; D’Cruz and Klein, 2005; Fontenot et al., 2005a). Furthermore, it also remains to be established in how far CD28 costimulation may directly influence the survival of Treg precursors through controlling pro-survival genes such as Bcl-xL, akin to its function in mature, “conventional” T cells (Boise et al., 1995; Shi et al., 1995; Noel et al., 1996; Radvanyi et al., 1996). However, given the evidence that the PI3-kinase pathway is important for induction of Bcl-xL by CD28 (Burr et al., 2001; Okkenhaug et al., 2001), yet that the PI3K interacting motif in CD28 is dispensable for efficient Treg induction (Tai et al., 2005; Lio et al., 2010; Vang et al., 2010), this scenario appears less likely.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (KL 1228/3-1 to Ludger Klein and Maria Hinterberger; SFB 571 to Ludger Klein and Gerald Wirnsberger).

References

Apostolou, I., Sarukhan, A., Klein, L., and von Boehmer, H. (2002). Origin of regulatory T cells with known specificity for antigen. Nat. Immunol. 3, 756–763.

Aschenbrenner, K., D’Cruz, L. M., Vollmann, E. H., Hinterberger, M., Emmerich, J., Swee, L. K., Rolink, A., and Klein, L. (2007). Selection of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells specific for self antigen expressed and presented by Aire+ medullary thymic epithelial cells. Nat. Immunol. 8, 351–358.

Atibalentja, D. F., Byersdorfer, C. A., and Unanue, E. R. (2009). Thymus-blood protein interactions are highly effective in negative selection and regulatory T cell induction. J. Immunol. 183, 7909–7918.

Barnes, M. J., Krebs, P., Harris, N., Eidenschenk, C., Gonzalez-Quintial, R., Arnold, C. N., Crozat, K., Sovath, S., Moresco, E. M., Theofilopoulos, A. N., Beutler, B., and Hoebe, K. (2009). Commitment to the regulatory T cell lineage requires CARMA1 in the thymus but not in the periphery. PLoS Biol. 7, e51.

Bayer, A. L., Lee, J. Y., de la Barrera, A., Surh, C. D., and Malek, T. R. (2008). A function for IL-7R for CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T regulatory cells. J. Immunol. 181, 225–234.

Bayer, A. L., Yu, A., Adeegbe, D., and Malek, T. R. (2005). Essential role for interleukin-2 for CD4(+)CD25(+) T regulatory cell development during the neonatal period. J. Exp. Med. 201, 769–777.

Boise, L. H., Minn, A. J., Noel, P. J., June, C. H., Accavitti, M. A., Lindsten, T., and Thompson, C. B. (1995). CD28 costimulation can promote T cell survival by enhancing the expression of Bcl-XL. Immunity 3, 87–98.

Borriello, F., Sethna, M. P., Boyd, S. D., Schweitzer, A. N., Tivol, E. A., Jacoby, D., Strom, T. B., Simpson, E. M., Freeman, G. J., and Sharpe, A. H. (1997). B7-1 and B7-2 have overlapping, critical roles in immunoglobulin class switching and germinal center formation. Immunity 6, 303–313.

Bour-Jordan, H., Esensten, J. H., Martinez-Llordella, M., Penaranda, C., Stumpf, M., and Bluestone, J. A. (2011). Intrinsic and extrinsic control of peripheral T-cell tolerance by costimulatory molecules of the CD28/B7 family. Immunol. Rev. 241, 180–205.

Burchill, M. A., Yang, J., Vang, K. B., Moon, J. J., Chu, H. H., Lio, C. W., Vegoe, A. L., Hsieh, C. S., Jenkins, M. K., and Farrar, M. A. (2008). Linked T cell receptor and cytokine signaling govern the development of the regulatory T cell repertoire. Immunity 28, 112–121.

Burr, J. S., Savage, N. D., Messah, G. E., Kimzey, S. L., Shaw, A. S., Arch, R. H., and Green, J. M. (2001). Cutting edge: distinct motifs within CD28 regulate T cell proliferation and induction of Bcl-XL. J. Immunol. 166, 5331–5335.

D’Cruz, L. M., and Klein, L. (2005). Development and function of agonist-induced CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells in the absence of interleukin 2 signaling. Nat. Immunol. 6, 1152–1159.

Deenick, E. K., Elford, A. R., Pellegrini, M., Hall, H., Mak, T. W., and Ohashi, P. S. (2010). c-Rel but not NF-kappaB1 is important for T regulatory cell development. Eur. J. Immunol. 40, 677–681.

Feuerer, M., Jiang, W., Holler, P. D., Satpathy, A., Campbell, C., Bogue, M., Mathis, D., and Benoist, C. (2007). Enhanced thymic selection of FoxP3+ regulatory T cells in the NOD mouse model of autoimmune diabetes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 18181–18186.

Fontenot, J. D., Rasmussen, J. P., Gavin, M. A., and Rudensky, A. Y. (2005a). A function for interleukin 2 in Foxp3-expressing regulatory T cells. Nat. Immunol. 6, 1142–1151.

Fontenot, J. D., Rasmussen, J. P., Williams, L. M., Dooley, J. L., Farr, A. G., and Rudensky, A. Y. (2005b). Regulatory T cell lineage specification by the forkhead transcription factor foxp3. Immunity 22, 329–341.

Fraser, J. D., Irving, B. A., Crabtree, G. R., and Weiss, A. (1991). Regulation of interleukin-2 gene enhancer activity by the T cell accessory molecule CD28. Science 251, 313–316.

Gavin, M. A., Rasmussen, J. P., Fontenot, J. D., Vasta, V., Manganiello, V. C., Beavo, J. A., and Rudensky, A. Y. (2007). Foxp3-dependent programme of regulatory T-cell differentiation. Nature 445, 771–775.

Hill, J. A., Feuerer, M., Tash, K., Haxhinasto, S., Perez, J., Melamed, R., Mathis, D., and Benoist, C. (2007). Foxp3 transcription-factor-dependent and -independent regulation of the regulatory T cell transcriptional signature. Immunity 27, 786–800.

Hinterberger, M., Aichinger, M., da Costa, O. P., Voehringer, D., Hoffmann, R., and Klein, L. (2010). Autonomous role of medullary thymic epithelial cells in central CD4(+) T cell tolerance. Nat. Immunol. 11, 512–519.

Hsieh, C. S., Zheng, Y., Liang, Y., Fontenot, J. D., and Rudensky, A. Y. (2006). An intersection between the self-reactive regulatory and nonregulatory T cell receptor repertoires. Nat. Immunol. 7, 401–410.

Isomura, I., Palmer, S., Grumont, R. J., Bunting, K., Hoyne, G., Wilkinson, N., Banerjee, A., Proietto, A., Gugasyan, R., Wu, L., McNally, A., Steptoe, R. J., Thomas, R., Shannon, M. F., and Gerondakis, S. (2009). c-Rel is required for the development of thymic Foxp3+ CD4 regulatory T cells. J. Exp. Med. 206, 3001–3014.

Jenkins, M. K., Taylor, P. S., Norton, S. D., and Urdahl, K. B. (1991). CD28 delivers a costimulatory signal involved in antigen-specific IL-2 production by human T cells. J. Immunol. 147, 2461–2466.

Jordan, M. S., Boesteanu, A., Reed, A. J., Petrone, A. L., Holenbeck, A. E., Lerman, M. A., Naji, A., and Caton, A. J. (2001). Thymic selection of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells induced by an agonist self-peptide. Nat. Immunol. 2, 301–306.

Josefowicz, S. Z., and Rudensky, A. (2009). Control of regulatory T cell lineage commitment and maintenance. Immunity 30, 616–625.

Kawahata, K., Misaki, Y., Yamauchi, M., Tsunekawa, S., Setoguchi, K., Miyazaki, J., and Yamamoto, K. (2002). Generation of CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T cells from autoreactive T cells simultaneously with their negative selection in the thymus and from nonautoreactive T cells by endogenous TCR expression. J. Immunol. 168, 4399–4405.

Kirberg, J., Baron, A., Jakob, S., Rolink, A., Karjalainen, K., and von Boehmer, H. (1994). Thymic selection of CD8+ single positive cells with a class II major histocompatibility complex-restricted receptor. J. Exp. Med. 180, 25–34.

Lahl, K., Mayer, C. T., Bopp, T., Huehn, J., Loddenkemper, C., Eberl, G., Wirnsberger, G., Dornmair, K., Geffers, R., Schmitt, E., Buer, J., and Sparwasser, T. (2009). Nonfunctional regulatory T cells and defective control of Th2 cytokine production in natural scurfy mutant mice. J. Immunol. 183, 5662–5672.

Lin, W., Haribhai, D., Relland, L. M., Truong, N., Carlson, M. R., Williams, C. B., and Chatila, T. A. (2007). Regulatory T cell development in the absence of functional Foxp3. Nat. Immunol. 8, 359–368.

Lindstein, T., June, C. H., Ledbetter, J. A., Stella, G., and Thompson, C. B. (1989). Regulation of lymphokine messenger RNA stability by a surface-mediated T cell activation pathway. Science 244, 339–343.

Lio, C. W., Dodson, L. F., Deppong, C. M., Hsieh, C. S., and Green, J. M. (2010). CD28 facilitates the generation of Foxp3- cytokine responsive regulatory T cell precursors. J. Immunol. 184, 6007–6013.

Lio, C. W., and Hsieh, C. S. (2008). A two-step process for thymic regulatory T cell development. Immunity 28, 100–111.

Lio, C. W., and Hsieh, C. S. (2011). Becoming self-aware: the thymic education of regulatory T cells. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 23, 213–219.

Lohr, J., Knoechel, B., Kahn, E. C., and Abbas, A. K. (2004). Role of B7 in T cell tolerance. J. Immunol. 173, 5028–5035.

Long, M., Park, S. G., Strickland, I., Hayden, M. S., and Ghosh, S. (2009). Nuclear factor-kappaB modulates regulatory T cell development by directly regulating expression of Foxp3 transcription factor. Immunity 31, 921–931.

Malek, T. R., Yu, A., Vincek, V., Scibelli, P., and Kong, L. (2002). CD4 regulatory T cells prevent lethal autoimmunity in IL-2Rbeta-deficient mice. Implications for the nonredundant function of IL-2. Immunity 17, 167–178.

Mayack, S. R., and Berg, L. J. (2006). Cutting edge: an alternative pathway of CD4+ T cell differentiation is induced following activation in the absence of gamma-chain-dependent cytokine signals. J. Immunol. 176, 2059–2063.

Medoff, B. D., Sandall, B. P., Landry, A., Nagahama, K., Mizoguchi, A., Luster, A. D., and Xavier, R. J. (2009). Differential requirement for CARMA1 in agonist-selected T-cell development. Eur. J. Immunol. 39, 78–84.

Noel, P. J., Boise, L. H., Green, J. M., and Thompson, C. B. (1996). CD28 costimulation prevents cell death during primary T cell activation. J. Immunol. 157, 636–642.

Okkenhaug, K., Wu, L., Garza, K. M., La Rose, J., Khoo, W., Odermatt, B., Mak, T. W., Ohashi, P. S., and Rottapel, R. (2001). A point mutation in CD28 distinguishes proliferative signals from survival signals. Nat. Immunol. 2, 325–332.

Pacholczyk, R., Ignatowicz, H., Kraj, P., and Ignatowicz, L. (2006). Origin and T cell receptor diversity of Foxp3+CD4+CD25+ T cells. Immunity 25, 249–259.

Papiernik, M., de Moraes, M. L., Pontoux, C., Vasseur, F., and Penit, C. (1998). Regulatory CD4 T cells: expression of IL-2R alpha chain, resistance to clonal deletion and IL-2 dependency. Int. Immunol. 10, 371–378.

Picca, C. C., Oh, S., Panarey, L., Aitken, M., Basehoar, A., and Caton, A. J. (2009). Thymocyte deletion can bias Treg formation toward low-abundance self-peptide. Eur. J. Immunol. 39, 3301–3306.

Radvanyi, L. G., Shi, Y., Vaziri, H., Sharma, A., Dhala, R., Mills, G. B., and Miller, R. G. (1996). CD28 costimulation inhibits TCR-induced apoptosis during a primary T cell response. J. Immunol. 156, 1788–1798.

Ribot, J., Romagnoli, P., and van Meerwijk, J. P. (2006). Agonist ligands expressed by thymic epithelium enhance positive selection of regulatory T lymphocytes from precursors with a normally diverse TCR repertoire. J. Immunol. 177, 1101–1107.

Ruan, Q., Kameswaran, V., Tone, Y., Li, L., Liou, H. C., Greene, M. I., Tone, M., and Chen, Y. H. (2009). Development of Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells is driven by the c-Rel enhanceosome. Immunity 31, 932–940.

Rudd, C. E., Taylor, A., and Schneider, H. (2009). CD28 and CTLA-4 coreceptor expression and signal transduction. Immunol. Rev. 229, 12–26.

Sakaguchi, S. (2004). Naturally arising CD4+ regulatory T cells for immunologic self-tolerance and negative control of immune responses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 22, 531–562.

Salomon, B., Lenschow, D. J., Rhee, L., Ashourian, N., Singh, B., Sharpe, A., and Bluestone, J. A. (2000). B7/CD28 costimulation is essential for the homeostasis of the CD4+CD25+ immunoregulatory T cells that control autoimmune diabetes. Immunity 12, 431–440.

Sanchez-Lockhart, M., Graf, B., and Miller, J. (2008). Signals and sequences that control CD28 localization to the central region of the immunological synapse. J. immunol. 181, 7639–7648.

Schmidt-Supprian, M., Tian, J., Grant, E. P., Pasparakis, M., Maehr, R., Ovaa, H., Ploegh, H. L., Coyle, A. J., and Rajewsky, K. (2004). Differential dependence of CD4+CD25+ regulatory and natural killer-like T cells on signals leading to NF-kappaB activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 4566–4571.

Setoguchi, R., Hori, S., Takahashi, T., and Sakaguchi, S. (2005). Homeostatic maintenance of natural Foxp3(+) CD25(+) CD4(+) regulatory T cells by interleukin (IL)-2 and induction of autoimmune disease by IL-2 neutralization. J. Exp. Med. 201, 723–735.

Shahinian, A., Pfeffer, K., Lee, K. P., Kundig, T. M., Kishihara, K., Wakeham, A., Kawai, K., Ohashi, P. S., Thompson, C. B., and Mak, T. W. (1993). Differential T cell costimulatory requirements in CD28-deficient mice. Science 261, 609–612.

Shi, Y., Radvanyi, L. G., Sharma, A., Shaw, P., Green, D. R., Miller, R. G., and Mills, G. B. (1995). CD28-mediated signaling in vivo prevents activation-induced apoptosis in the thymus and alters peripheral lymphocyte homeostasis. J. Immunol. 155, 1829–1837.

Simons, D. M., Picca, C. C., Oh, S., Perng, O. A., Aitken, M., Erikson, J., and Caton, A. J. (2010). How specificity for self-peptides shapes the development and function of regulatory T cells. J. Leukoc. Biol. 88, 1099–1107.

Tai, X., Cowan, M., Feigenbaum, L., and Singer, A. (2005). CD28 costimulation of developing thymocytes induces Foxp3 expression and regulatory T cell differentiation independently of interleukin 2. Nat. Immunol. 6, 152–162.

Tang, Q., Henriksen, K. J., Bi, M., Finger, E. B., Szot, G., Ye, J., Masteller, E. L., McDevitt, H., Bonyhadi, M., and Bluestone, J. A. (2004). In vitro-expanded antigen-specific regulatory T cells suppress autoimmune diabetes. J. Exp. Med. 199, 1455–1465.

Tang, Q., Henriksen, K. J., Boden, E. K., Tooley, A. J., Ye, J., Subudhi, S. K., Zheng, X. X., Strom, T. B., and Bluestone, J. A. (2003). Cutting edge: CD28 controls peripheral homeostasis of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. J. Immunol. 171, 3348–3352.

Vang, K. B., Yang, J., Mahmud, S. A., Burchill, M. A., Vegoe, A. L., and Farrar, M. A. (2008). IL-2, -7, and -15, but not thymic stromal lymphopoeitin, redundantly govern CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cell development. J. Immunol. 181, 3285–3290.

Vang, K. B., Yang, J., Pagan, A. J., Li, L. X., Wang, J., Green, J. M., Beg, A. A., and Farrar, M. A. (2010). Cutting edge: CD28 and c-Rel-dependent pathways initiate regulatory T cell development. J. Immunol. 184, 4074–4077.

Visekruna, A., Huber, M., Hellhund, A., Bothur, E., Reinhard, K., Bollig, N., Schmidt, N., Joeris, T., Lohoff, M., and Steinhoff, U. (2010). c-Rel is crucial for the induction of Foxp3(+) regulatory CD4(+) T cells but not T(H)17 cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 40, 671–676.

Wirnsberger, G., Hinterberger, M., and Klein, L. (2011). Regulatory T-cell differentiation versus clonal deletion of autoreactive thymocytes. Immunol. Cell Biol. 89, 45–53.

Wirnsberger, G., Mair, F., and Klein, L. (2009). Regulatory T cell differentiation of thymocytes does not require a dedicated antigen-presenting cell but is under T cell-intrinsic developmental control. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 10278–10283.

Yao, Z., Kanno, Y., Kerenyi, M., Stephens, G., Durant, L., Watford, W. T., Laurence, A., Robinson, G. W., Shevach, E. M., Moriggl, R., Hennighausen, L., Wu, C., and O’Shea, J. J. (2007). Nonredundant roles for Stat5a/b in directly regulating Foxp3. Blood 109, 4368–4375.

Keywords: regulatory T cell, thymocyte development, thymus, tolerance, costimulation, thymus epithelium, CD28, B7

Citation: Hinterberger M Wirnsberger G and Klein L (2011) B7/CD28 in central tolerance: costimulation promotes maturation of regulatory T cell precursors and prevents their clonal deletion. Front. Immun. 2:30. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2011.00030

Received: 15 June 2011;

Paper pending published: 07 July 2011;

Accepted: 14 July 2011;

Published online: 25 July 2011.

Edited by:

Stephen M. Anderton, University of Edinburgh, UKReviewed by:

Wayne Hancock, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, USAPeter M. van Endert, Université Paris Descartes/INSERM, France

Copyright: © 2011 Hinterberger, Wirnsberger and Klein. This is an open-access article subject to a non-exclusive license between the authors and Frontiers Media SA, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in other forums, provided the original authors and source are credited and other Frontiers conditions are complied with.

*Correspondence: Ludger Klein, Institute for Immunology, University of Munich, Goethestrasse 31, 80336 Munich, Germany. e-mail: ludger.klein@med.unimuenchen.de