- 1 INSERM U1043, Toulouse, France

- 2 CNRS U5282, Toulouse, France

- 3 Centre de Physiopathologie de Toulouse Purpan, Université Paul Sabatier, Université de Toulouse, Toulouse, France

The immunosuppressive regimens currently used in transplantation to prevent allograft destruction by the host’s immune system have deleterious side effects and fail to control chronic rejection processes. Induction of donor-specific non-responsiveness (i.e., immunological tolerance) to transplants would solve these problems and would substantially ameliorate patients’ quality of life. It has been proposed that bone marrow or hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation, and resulting (mixed) hematopoietic chimerism, lead to immunological tolerance to organs of the same donor. However, a careful analysis of the literature, performed here, clearly establishes that whereas hematopoietic chimerism substantially prolongs allograft survival, it does not systematically prevent chronic rejection. Moreover, the cytotoxic conditioning regimens used to achieve long-term persistence of chimerism are associated with severe side effects that appear incompatible with a routine use in the clinic. Several laboratories recently embarked on different studies to develop alternative strategies to overcome these issues. We discuss here recent advances obtained by combining regulatory T cell infusion with bone-marrow transplantation. In experimental settings, this attractive approach allows development of genuine immunological tolerance to donor tissues using clinically relevant conditioning regimens.

Introduction

The immunosuppressive regimens developed since the discovery of cyclosporine A showed ever increasing efficiency in reducing the severity and occurrence of acute rejection episodes. Recently, a systematic analysis of the literature firmly identified acute rejection events as a bad prognosis factor for long-term graft survival (Wu et al., 2009). Since immunosuppressive drugs efficiently control acute rejection, this explains how they significantly improved allograft survival over the past 40 years despite failing to have a direct impact on chronic rejection. The failure of current treatments to control chronic rejection processes combined with their deleterious side-effects urgently call for development of novel therapies against allograft rejection (Kahan, 2003; Meier-Kriesche and Kaplan, 2011).

During lymphocyte development in primary lymphoid organs, and due to the random rearrangement of genes encoding the antigen receptor, many autospecific T and B cell precursors arise. Since such cells would cause devastating autoimmune pathology, the natural mechanisms involved in the induction of self-tolerance play a crucial role in the survival of the species (Waldmann, 2010). Self-tolerance is defined as a state in which autoimmune attack is either prevented or deviated to non-detrimental responses (Walker and Abbas, 2002; Hogquist et al., 2005). It allows development of protective immunity and is therefore very specific. It appears very attractive to manipulate the mechanisms involved in self-tolerance in order to make them prevent allograft rejection. If successful, this would allow for indefinite survival of grafts.

Tolerance-Induction by Cells of Hematopoietic Origin: Proof of Principle

Several layers of complementary mechanisms ensure tolerance to self-antigens. Interestingly, considerable insight into these mechanisms was obtained through transplantation models and by manipulating the development of the immune system early in life, during embryogenesis or in neonates. Owen (1945) first observed that dizygotic twin cattle, that almost invariably develop placental anastomosis, “have identical blood types” as adults and he concluded “the critical interchange is of embryonal cells ancestral to the erythrocytes”. Later, Billingham, Medawar, and colleagues showed that these chimeric twins “accepted” each other’s skins when grafted later in life (Billingham et al., 1952). In a 1953 landmark paper, the same group showed that skin allograft survival could be substantially prolonged by injecting a single-cell suspension of donor tissues in utero or into neonates (Billingham et al., 1953). Such treatment led to varying levels of hematopoietic chimerism, which was later shown to be critically involved in allograft survival (Lubaroff and Silvers, 1973; Wood and Streilein, 1982; Wren et al., 1993; Alard et al., 1995).

In the two systems described above, lymphocytes developed in the presence of (and thus learned to be tolerant to) donor antigens. However, in adults the situation is more complicated as, in addition to developing lymphocytes, preexisting donor-specific mature cells would also need to be rendered tolerant. To bypass this concern, several laboratories decided to deplete the pool of mature T cells (Main and Prehn, 1955; Trentin, 1956; Brocades Zaalberg et al., 1957). These groups first experimented this approach through the elimination of all hematopoietic cells. Recipient mice were lethally irradiated or treated with cytotoxic drugs, reconstituted with donor bone marrow, and grafted with skin. These strategies invariably led to substantially increased survival of homo- and xenografts. More recently, Ildstad and Sachs (1984) definitely validated these observations by inducing long-term survival of allogenic and xenogenic skin grafts using a comparable approach. Similar results were obtained in the rat for heart and skin grafts (Colson et al., 1995b; Orloff et al., 1995). Combined, these observations clearly demonstrated that hematopoietic chimerism leads to prolonged survival of allografts.

Cells of Hematopoietic Origin Induce T Cell Tolerance by Induction of Apoptosis and Anergy

To address the question of how cells of hematopoietic origin induce tolerance, researchers needed a means to identify T cell precursors specific for a given antigen. Kappler et al. (1987b) showed that practically all T cells expressing the variable TCR segment Vβ17a, representing up to 15% of the T cell repertoire in certain mouse-strains, recognized the MHC class II molecule I-E. Given that they had developed an antibody against this Vβ domain, the mechanisms involved in T cell tolerance to I-E could now be analyzed. It was shown in I-E expressing mice that Vβ17a+ T cell precursors were eliminated at an immature stage during thymic development (Kappler et al., 1987a). The following year, the same authors further characterized this mechanism and showed that clonal deletion requires the expression of the negatively selecting ligand by thymic cells of hematopoietic origin (Kappler et al., 1988). Many other illustrations of clonal deletion of T cells expressing given TCR Vβ segments by endogenous or exogenous superantigens have since been published (MacDonald et al., 1988b; Luther and Acha-Orbea, 1997).

Could thymic elimination of reactive clones also be involved in the neonatal induction of tolerance to alloantigens? This question was addressed by MacDonald et al. (1988a) who showed that the transfer of superantigen-expressing spleen cells into neonates lead to the intrathymic deletion of superantigen-reactive T cells. Similar conclusions were rapidly drawn by others (Streilein, 1991). Later, intrathymic deletion of donor-specific precursors was also reported in adult mixed hematopoietic chimeras using TCR transgenic cells as a tracer population (Manilay et al., 1998).

Thus, thymic cells of hematopoietic origin are involved in deletion of autospecific T cell-precursors and mixed hematopoietic chimerism leads to deletion of alloreactive cells. Using thymic organ cultures to analyze the involvement of different stromal cells, it was shown that dendritic cells (DC) are critically involved in this process (Matzinger and Guerder, 1989; Jenkinson et al., 1992; Anderson et al., 1998). This was further confirmed using a transgenic mouse model in which TCR ligand-expression was essentially restricted to DC using the CD11c promoter (Brocker et al., 1997). Among the thymic DC subtypes, both Sirpα+ and Sirpα − conventional DC have been implicated in central tolerance-induction by deletion (Wu and Shortman, 2005; Baba et al., 2009). However, other populations of hematopoietic cells may also play a role in this process, including CD4+CD8+ thymocytes, thymic macrophages and B cells (Pircher et al., 1992, 1993; Kleindienst et al., 2000), and circulating peripheral DC (Bonasio et al., 2006).

Combined, the data discussed thus far showed that DC, and potentially other cells of hematopoietic origin, contribute to tolerance induction by elimination of developing thymocytes. Using conditioning regimens that totally deplete host T cells before bone-marrow transplantation, it was proposed that this mechanism was necessary and sufficient for maintenance of tolerance and that peripheral mechanisms do not contribute to this process (Khan et al., 1996). However, other mechanisms could be involved when less aggressive regimens are used. In normal mice, it has been proposed that deletion of autospecific T cells that escaped thymic selection could also occur in peripheral lymphoid organs and could be involved in the maintenance of self-tolerance (Russell, 1995). To test if similar mechanisms were involved in induction of tolerance to alloantigens following bone-marrow transplantation, Wekerle et al. (1998) tracked T cells specific for a given superantigen in thymectomized mice transplanted with allogeneic bone-marrow under cover of CTLA4-Ig and antibody to CD154 (“co-stimulatory blockade”). They observed a rapid deletion of donor-specific host T cells from the peripheral CD4+ compartment. This observation was later confirmed using a TCR transgenic mouse model (Kurtz et al., 2004) and it was further shown that peripheral deletion relies essentially on two types of mechanisms: activation-induced cell death, a Fas-dependent process that can be promoted by IL-2 and that leads to apoptosis of activated T cells when restimulated with high doses of antigen (Lenardo, 1991; Ju et al., 1995; Russell, 1995); and passive cell death or death “by neglect,” a Fas-independent process that can be prevented by overexpression of Bcl-2 or Bcl-xL and that leads to T cell apoptosis when stimulated with low dose of antigen and/or in the absence of co-stimulatory signals (Boise et al., 1995; Van Parijs et al., 1996; Wekerle et al., 2001). It was also shown that in addition to DC, other populations of hematopoietic cells such as B cells have the capacity to delete allospecific precursors from the peripheral T cell compartment (Fehr et al., 2008a,b). Finally, hematopoietic cells can also cause T cell tolerance by inducing a non-responsive state called clonal anergy (Rammensee et al., 1989; Tomita et al., 1994; Hawiger et al., 2001). Combined, the cited reports clearly show that cells of hematopoietic origin can induce “passive” tolerance (i.e., apoptosis and anergy).

Can Hematopoietic Cells Induce Active Regulatory Mechanisms?

T lymphocytes from chimeric mice in which radioresistant cells express MHC molecules but hematopoietic cells do not, vigorously react to self-antigens in vitro (van Meerwijk and MacDonald, 1999) and in some well-defined experimental conditions in vivo (Hudrisier et al., 2003). Combined with the observations listed above, this shows that hematopoietic cells play a central role in the deletion and/or functional inactivation of self-reactive precursors. However, passive mechanisms are not sufficient to fully control self-reactivity. Individuals carrying a mutated FOXP3 gene develop the rapidly lethal autoimmune syndrome immuno dysfunction, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked (IPEX). This is explained by the fact that Foxp3 is required for the programming of a population of regulatory CD4+ T lymphocytes (Treg) that inhibit and/or divert innate and adaptive immune responses, mainly those directed against self-antigens. Genuine tolerance to self, and consequently probably to non-self-antigens, therefore requires Treg (Fontenot and Rudensky, 2005; Sakaguchi et al., 2006; Shevach et al., 2006).

Given their central (though not exclusive) role in the control of autoimmune responses, it was probably not a very surprising finding that the Treg repertoire is strongly enriched in autospecific cells (Romagnoli et al., 2002; Hsieh et al., 2004). Development of self-antigen-specific Treg in the thymus depends on interaction of developing precursors with MHC/self-peptide ligands expressed by thymic epithelial cells (Bensinger et al., 2001; Romagnoli et al., 2005; Ribot et al., 2006, 2007; Aschenbrenner et al., 2007). Moreover, the transplantation of allogeneic thymic anlagen (i.e., the initial cluster of pluripotent embryonic cells from which the thymus will develop) into mice induces Treg-mediated tolerance to subsequent skin grafts of the same donor, again showing that thymic epithelial cells can select antigen-specific Treg (Le Douarin et al., 1996). However, the capacity to trigger Treg differentiation in the thymus is not a property restricted to epithelial cells as it has been reported that thymic DC are also involved in this process (Watanabe et al., 2005; Proietto et al., 2008; Wirnsberger et al., 2009). Moreover, induction of Treg differentiation by DC has also been reported in peripheral lymphoid organs under certain carefully controlled experimental conditions (reviewed by Romagnoli et al., 2008). It may therefore be hypothesized that hematopoietic chimerism can lead to differentiation and/or expansion of Treg specific for donor antigens and thus to the development of dominant tolerance. However, in experimental systems where the conditioning regimen used to induce mixed hematopoietic chimerism involved the total deletion of host T cells, transfer of syngeneic naïve CD4+ T cells into the recipient leads to bone-marrow rejection and to the concomitant loss of donor-specific transplantation tolerance (Wren et al., 1993). This result clearly demonstrated that hematopoietic chimerism per se is insufficient for induction of dominant tolerance to alloantigens. Given the non-redundant role of Treg in maintenance of self-tolerance, hematopoietic chimerism therefore appears unlikely to be sufficient for permanent survival of allografts.

Active tolerance mechanisms are not limited to those mediated by Treg. “Immune deviation” from a harmful Th1 to a less detrimental Th2 response has also been shown to play a role in control of immune responses (Rocken, 1996; Walker and Abbas, 2002). Alloreactive Th2 cytokine producing T cells have been observed after neonatal injection of lymphohematopoietic cells (Streilein, 1991) and immune deviation by IL-4 was shown to play a critical role in tolerance to alloantigens (Donckier et al., 1995). The hematopoietic (micro-)chimerism induced in this experimental model, which is critically required for the allograft tolerance (Lubaroff and Silvers, 1973), therefore appears to induce an active regulatory mechanism. However, this mechanism appears insufficient for induction of full immunological tolerance to alloantigens (see below). Stem-cell transplantation under cover of cyclophosphamide can induce tolerance to MHC-matched skin allografts in mice. It was shown that NKT cells, another immunoregulatory population, play a central role in this phenomenon (Iwai et al., 2006). Regulatory T cell populations other than Foxp3+ cells may therefore be induced by hematopoietic chimerism but their activity appears insufficient for prevention of chronic allograft rejection.

Does Hematopoietic Chimerism Induce Genuine Tolerance to Allografts?

As discussed above, hematopoietic chimerism is thought to be sufficient for induction of tolerance to allografts. The mechanisms involved include central and peripheral clonal deletion and anergy. After the initial reports on allograft tolerance in dizygotic cattle twins that had shared blood circulation during embryonic life, it became clear that most skin grafts were rejected in the long term (Stone et al., 1965, 1971). Second skin grafts from the same donor survived less long than the first grafts, but substantially longer than third party organs, showing that the tolerance mechanism had not waned away.

Also neonatal injection of allogeneic splenocytes, leading to hematopoietic microchimerism, is thought to induce tolerance to subsequent skin grafts. However, this procedure appeared to work only in a limited number of donor/host combinations. Importantly, most of the reported donor/host combinations concerned MHC congenic strains (i.e., expressing distinct MHC haplotypes on an identical genetic background) and chronic rejection was not systematically studied (Streilein and Klein, 1977). Moreover, even when acceptance of skin allografts was achieved, it did not correlate with immunological unresponsiveness (Streilein, 1991; Donckier et al., 1995).

In adult mice, lymphoablation was achieved using lethal total body irradiation or depleting antibodies to, e.g., CD4 and CD8. Myeloablation, required for induction of hematopoietic chimerism, was induced by the irradiation or administration of myeloablative drugs. Subsequent transplantation of allogenic or xenogenic bone marrow led to persistent chimerism (reviewed in Wekerle and Sykes, 1999; Cosimi and Sachs, 2004). Skin grafts from the bone-marrow donors could survive for prolonged periods, but success-rates were often well below 100% and chronic rejection was not studied. In some host/donor combinations, hematopoietic chimerism failed to prevent acute rejection of skin allografts (Boyse et al., 1970), and T cell reactivity to skin-specific antigens not expressed by hematopoietic cells was responsible for this observation (Scheid et al., 1972; Boyse et al., 1973). Also the survival of cardiac allografts was favored by hematopoietic chimerism (Steinmuller and Lofgreen, 1974). However, histological analysis of surviving hearts revealed frequent chronic rejection (Russell et al., 2001). Also in the rat, myelo- and lymphoablation followed by induction of hematopoietic chimerism was reported to prolong survival of skin, heart, and renal allografts (Slavin et al., 1978; Colson et al., 1995b; Orloff et al., 1995; Blom et al., 1996). However, chronic rejection was seldom adequately studied. It appears therefore that immunological tolerance to allografts is not systematically achieved by induction of hematopoietic chimerism in lymphoablated recipients.

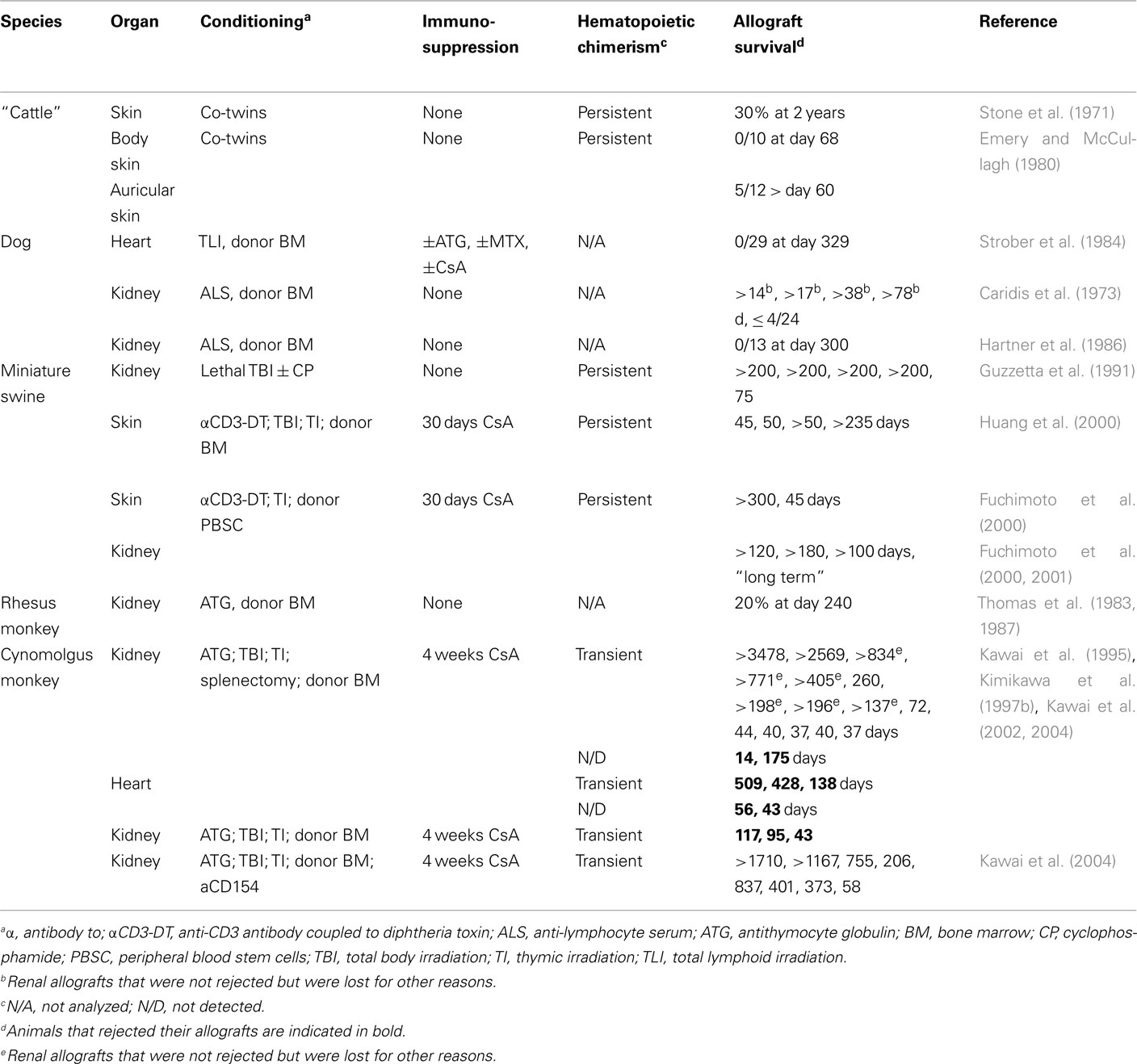

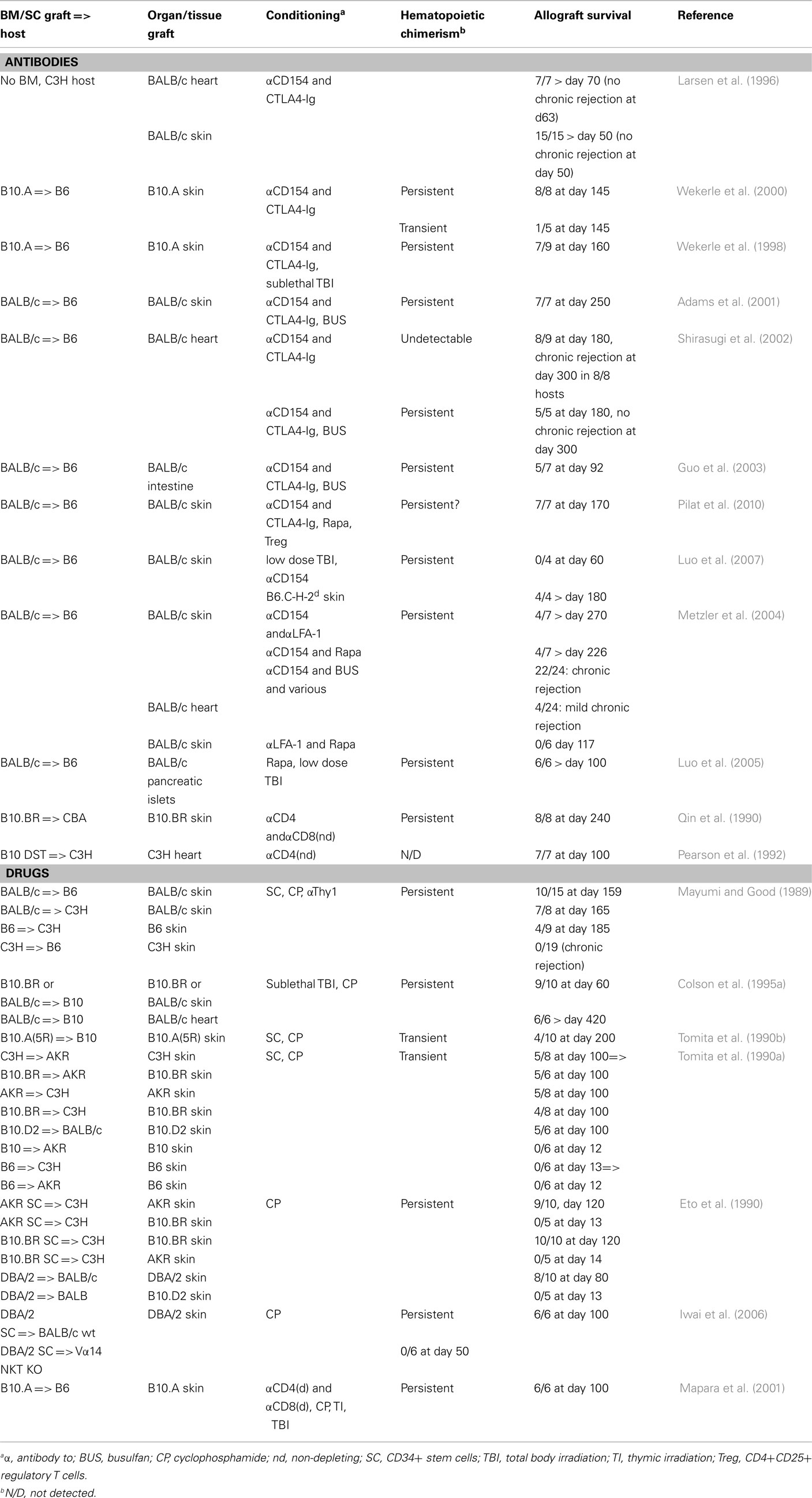

Hematopoietic chimerism can also be induced with non-lymphoablative regimens. Surprisingly, under certain of these conditions, allografts appear to do better than when lymphoablative conditioning is used (Table 1). Blocking the T cell co-stimulatory molecule CD28 with an Ig-fusion protein of its CTLA4-ligand (CTLA4-Ig), combined with inhibition of the CD40/CD40L (i.e., CD154) pathway involved in activation of antigen presenting and B cells, substantially prolongs heart and skin allograft survival (Larsen et al., 1996). However, histological signs of chronic rejection of cardiac allografts was observed in all thus conditioned mice (Shirasugi et al., 2002). When co-stimulatory blockade was combined with induction of hematopoietic chimerism, heart, skin, and also intestine allografts survived substantially longer and no chronic rejection was observed (Wekerle et al., 1998, 2000; Adams et al., 2001; Shirasugi et al., 2002; Guo et al., 2003). Transplantation tolerance in such settings was dominant and depended on Treg, at least during early stages (Bigenzahn et al., 2005; Domenig et al., 2005).

Table 1. Combined bone-marrow and organ transplantation in the mouse: non-myelo- and lymphoablative procedures.

Combined, these data indicate that hematopoietic chimerism per se appears insufficient for induction of transplantation tolerance. However, when combined with conditioning regimens that allow for development of dominant tolerance, prevention of chronic rejection can be achieved.

Induction of Hematopoietic Chimerism: Toward the Clinic

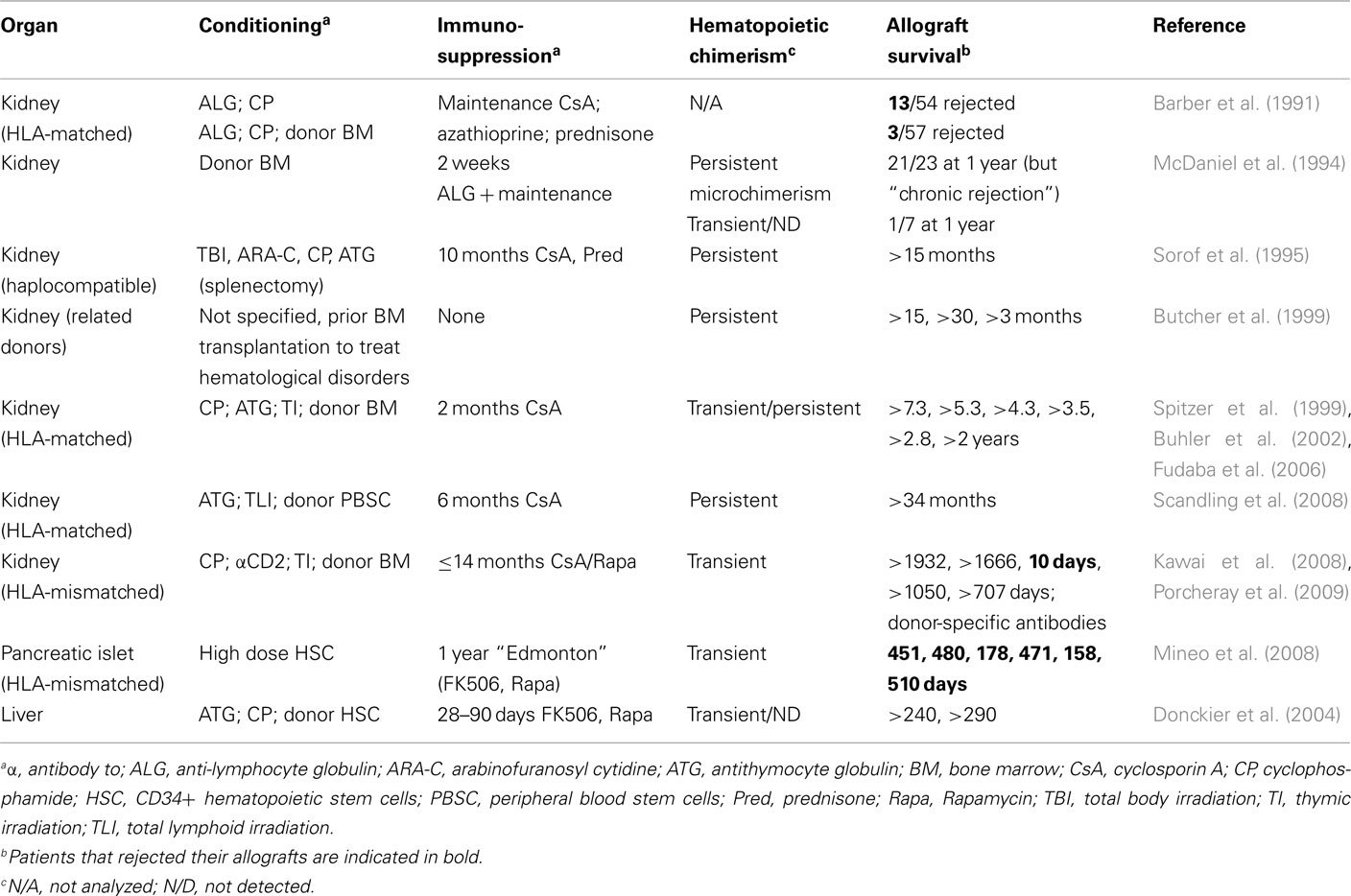

Given the very encouraging results obtained with mixed hematopoietic chimerism in rodents, several groups have attempted to induce hematopoietic chimerism and transplantation tolerance in large animal models (Wekerle and Sykes, 1999; Cosimi and Sachs, 2004; Horner et al., 2006). Experimental protocols are necessarily more complex than in rodents since adult recipients were used and high dose whole body irradiation is associated with a too high level of morbidity. A combination of immunosuppressive drugs and antibodies, as well as lower levels of irradiation or irradiation limited to lymphoid organs, was therefore used as conditioning regimen (Table 2). In miniature swine, a preconditioning of T cell depletion, low dose total body irradiation, thymic irradiation, and splenectomy, followed by bone-marrow and skin transplantation, led to persistent hematopoietic chimerism in five out of six animals. Four of these animals were transplanted with donor skin. Half of these animals appeared to accept, but the other half rejected the skin allografts (Fuchimoto et al., 2000). Also using a milder conditioning regimen, persistent chimerism was obtained in miniature swine and one out of two skin grafts appeared to be permanently accepted (Fuchimoto et al., 2000). When the latter protocol was used for kidney transplantation, four out of four allografts survived more than 100 days (Fuchimoto et al., 2000, 2001). Therefore, as observed in rodents, persistent hematopoietic chimerism led to an incomplete level of allograft tolerance that appeared efficient for protection of poorly immunogenic organs such as kidney but fails to prevent rejection of highly immunogenic skin allografts.

In Cynomolgus monkeys, a preconditioning regimen was used that consisted of T cell depletion, low dose total body irradiation, thymic irradiation, and splenectomy, followed by bone-marrow and kidney transplantation (Kawai et al., 1995, 2002, 2004; Kimikawa et al., 1997b). Only transient hematopoietic chimerism was observed, but nevertheless 8 out of 15 grafts did not show signs of rejection (Table 2). An acute cellular rejection process led to the loss of the other grafts (Kimikawa et al., 1997a; Kawai et al., 1999). A similar preconditioning regimen was used for monkeys that received a cardiac allograft. Three out of five animals developed transient chimerism, but all five hearts were eventually lost by a rejection-process characterized by cellular infiltrates (Kawai et al., 2002). The observation that kidney allografts were more likely to be accepted than heart allografts confirmed earlier data on transplantation in miniature swine that, interestingly, also showed that kidneys can play an important role in tolerance to heart allografts (Madsen et al., 1998; Mezrich et al., 2003a,b). Taken together these data highlight the difficulty to obtain an efficient and persistent engraftment of hematopoietic stem cells in large animal models. When only transient, hematopoietic chimerism induces tolerance mechanisms that are probably different from and less efficient than those induced in hosts with long-term persistence of hematopoietic donor cells.

Induction of Hematopoietic Chimerism: In the Clinic

Based on the promising results in monkeys, induction of hematopoietic chimerism for prevention of allograft rejection has also been performed in humans (Table 3). Infusion of donor bone-marrow showed some beneficial effect in renal allograft recipients (Monaco, 2003). Interestingly, in an early report in which large numbers of patients were described, infusion of donor bone marrow, leading to transient chimerism, inhibited acute but not chronic rejection (Barber et al., 1991; McDaniel et al., 1994). One of the first reported cases of long-term allograft survival achieved by induction of hematopoietic chimerism concerned a woman with end-stage renal disease secondary to multiple myeloma (Spitzer et al., 1999). The patient received an immunosuppressive but non-myeloablative conditioning regimen. HLA-matched bone marrow and kidney from the patient’s sister were transplanted and the immunosuppressive drug cyclosporine A administered for 73 days. Whereas the hematopoietic chimerism disappeared after discontinuation of immunosuppression, the kidney remained functional for at least another 7 years (Fudaba et al., 2006). In total, six multiple myeloma patients receiving this treatment have been reported and all maintained renal function after discontinuation of immunosuppression for 2–7 years (Spitzer et al., 1999; Buhler et al., 2002; Fudaba et al., 2006). Stem-cell transfusion was also shown to have a beneficial effect in liver transplantation (Donckier et al., 2004). Another example concerned a patient with end-stage renal disease who received an HLA-matched kidney graft. The conditioning regimen, which included total lymphoid irradiation, immunosuppression, and a graft of mobilized CD34+ stem cells, led to persistent hematopoietic chimerism. At the time of publication, the renal graft had remained functional for 34 months (Scandling et al., 2008).

Induction of hematopoietic chimerism followed by kidney transplantation was also performed with HLA single haplotype mismatched grafts (Kawai et al., 2008), a clinically important setting. Five patients with end-stage renal disease received an immunosuppressive but non-myeloablative preparative regimen and a combined bone-marrow/renal allograft. All developed a transient multi-lineage chimerism. Whereas one patient lost the allograft by acute humoral rejection 10 days post transplantation, four out of the five patients, treated with a combination of immunosuppressive drugs for up to 14 months, maintained renal function for up to 1400 days thereafter. Renal biopsies showed normal tissue for three of these patients, with some minor signs of chronic rejection for the fourth. In vitro studies suggested specific absence of T cell-responses to directly presented alloantigens. However, two out of the four patients later developed alloantibodies, one showing complement depositions in the graft (Porcheray et al., 2009). It needs to be emphasized that T cell reactivity to indirectly presented donor antigens is required for alloantibody-production by host B-lymphocytes. The apparent absence of T cell response to directly presented alloantigens and the production of alloantibodies are therefore not in contradiction. Combined, these studies suggested that long-term acceptance of (though not genuine immunological tolerance to) kidney allografts can be obtained by a therapy including induction of transient hematopoietic chimerism and therefore represented a major step forward in transplantation medicine.

Less promising results were obtained in a study in which HLA-mismatched pancreatic islets were transplanted into type I diabetes patients (Mineo et al., 2008). The conditioning regimen used was very mild but nevertheless led to transient hematopoietic chimerism. However, all four patients that initially adhered to immunosuppressive therapy lost graft-function rapidly after drug weaning.

A Role for Regulatory T Cells in Hematopoietic Chimerism-Associated Tolerance?

At this point, one might wonder if more work is warranted to obtain tolerance to (and therefore permanent acceptance of) organ allografts. When considering the very promising results obtained with kidney allografts in humans, one has to keep in mind that this organ might represent a special case. The human islet study failed, and the monkey and swine studies gave substantially less satisfying results with skin and heart allografts than with renal transplants. Moreover, in miniature swine it was shown that kidney allografts induced tolerance to heart allografts (Madsen et al., 1998). The thymus and Treg may play a role in this phenomenon (Yamada et al., 1999; Mezrich et al., 2003a).

To induce genuine immunological tolerance to donor tissues, hematopoietic chimerism needs to persist in the long term to continuously induce tolerance of newly developing lymphocytes in primary lymphoid organs. Indeed, if hematopoietic chimerism is only transient, mature allospecific lymphocytes will develop and, in the absence of dominant tolerance mechanisms, will eventually destroy the graft. Long-term hematopoietic chimerism has been achieved with very aggressive conditioning regimens inducing total host T cell depletion. However, the level of toxicity and the severe immunosuppression associated with this type of treatment do not allow their use in the clinic. Alternative conditioning regimens have been envisaged to avoid rejection of donor bone marrow while allowing for survival of part of the host T cells. They included the injection of non-depleting antibodies to block T cell co-stimulatory pathways and the injection of antibodies specific for some T cell markers upregulated upon activation. As described throughout this review, these methods gave very promising results in rodents. However, induction of a permanent chimerism was far more difficult to achieve in large animals. This observation might be largely responsible for the less satisfying results obtained with heart and skin allograft in miniature swine and primates. Moreover, antibody-based therapies can also generate unpredicted side effects that complicate translation into the clinic. For example, the use of anti-CD154 antibody in a non-human primate renal allograft model led to severe thromboembolic complications (Kawai et al., 2000; Koyama et al., 2004) due to CD154 expression on activated platelets and to CD40 expression on the vascular endothelium (Henn et al., 1998; Slupsky et al., 1998). The use of anti-CD154 has also been associated with impaired humoral immunity against influenza in a heart allograft model (Crowe et al., 2003). Antibodies targeting other T cell surface markers also present limitations as targeted molecules can be expressed by other populations, e.g., CD25 on Treg. While inhibiting the allogeneic response, such approaches could therefore prevent the establishment of regulatory mechanisms important for graft survival. They also non-specifically inhibit T cell-dependent immunity, including protective responses against pathogens. Finally, most of the protocols used in large animals or currently tested in the clinic require strong initial immunosuppressive treatments that induce major qualitative and quantitative modifications of the immune system that last for years. In conclusion, while highly promising, these strategies still need to be optimized before going into the clinic.

To overcome the issues listed above, several laboratories embarked on studies to evaluate the potential of Treg to promote allograft protection (reviewed by Li and Turka, 2010). The capacity of naturally occurring Treg to control allogeneic responses was already highlighted by Sakaguchi et al. (1995) landmark paper. Using in vivo activated polyclonal Treg with irrelevant specificity, Karim et al. (2005) first induced tolerance to allogeneic skin graft in lymphopenic Rag-deficient hosts reconstituted with naïve CD45RBhigh CD4+T cells (Karim et al., 2005). Similar results were obtained in another lymphopenic system with in vitro expanded donor-specific Treg (Golshayan et al., 2007). Interestingly, this approach also significantly prolonged skin allograft survival in unmanipulated wild-type hosts. In a transplantation-model across minor histocompatibility antigens, another group protected male skin graft from rejection by syngeneic female hosts using Foxp3-transduced male antigen-specific TCR transgenic CD4+ T cells (Chai et al., 2005). In another study, a genetically manipulated Treg population with direct and indirect alloantigen-specificity substantially prolonged skin allograft survival and delayed chronic rejection of heart allografts when co-injected with anti-CD8 antibody (Tsang et al., 2008). More recently, prevention of transplant arteriosclerosis and long-term survival of skin allograft were achieved with in vitro expanded naturally occurring CD127lowCD25+CD4+ human Treg in a chimeric humanized mouse system (Issa and Wood, 2010; Nadig et al., 2010). Combined, these reports demonstrated the capacity of Treg to delay rejection processes.

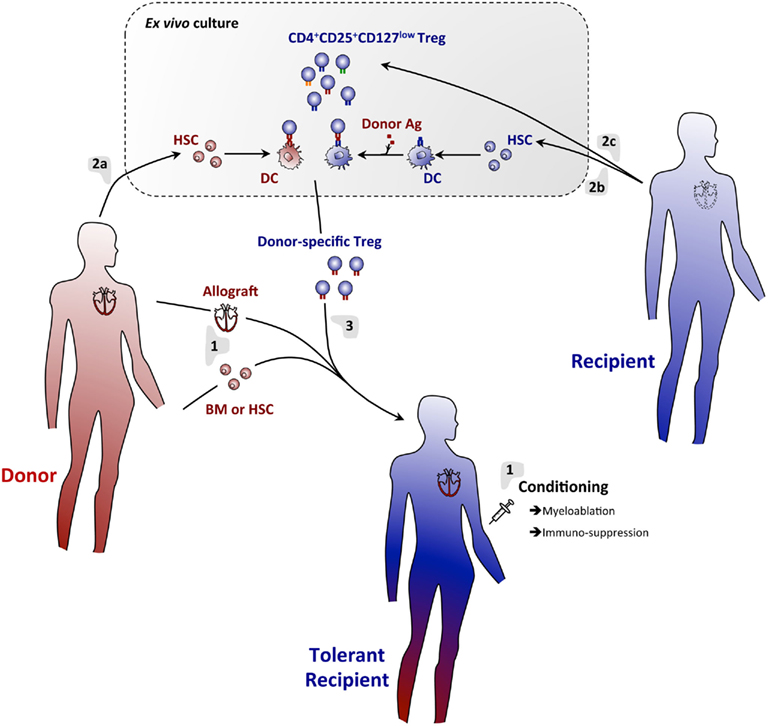

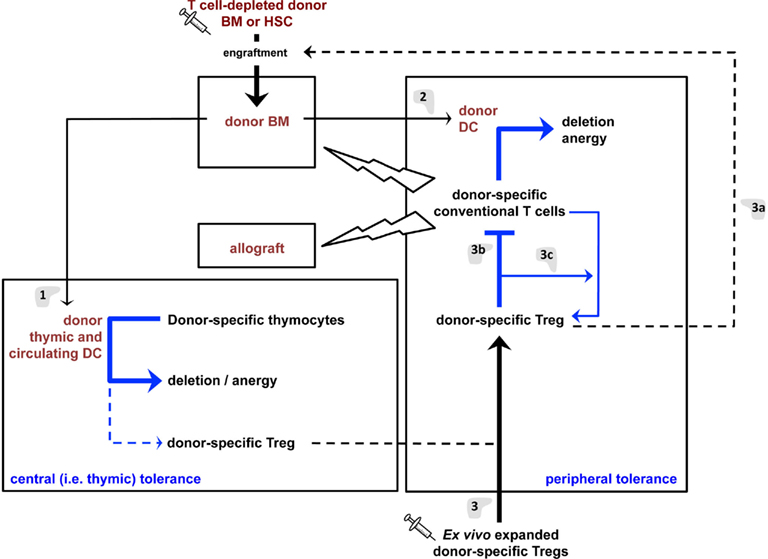

Based on the large body of literature on transplantation tolerance through hematopoietic chimerism and on the immunosuppressive potential of Treg, several laboratories decided to combine Treg infusion with bone-marrow transplantation (Figure 1). This method is expected to allow the establishment of complementary tolerance mechanisms, thus mimicking the complex network of checkpoints and regulatory systems naturally involved in maintenance of self-tolerance (Figure 2). Moreover, in addition to their general modulatory effects on the reactivity of the immune system, Treg expressing the transcription factor Foxp3 have the capacity to establish an immune-privileged niche for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cells after transplantation into non-irradiated recipients (Fujisaki et al., 2011). The co-injection of Treg with allogeneic bone-marrow should therefore promote its engraftment. Administration of donor-specific Treg prevented rejection of bone-marrow allografts in preconditioned mice (Joffre et al., 2004; Joffre and van Meerwijk, 2006). Promising results were later obtained using polyclonal donor Treg (Hanash and Levy, 2005). However, similar protocols failed to substantially prolong survival of skin and heart allografts (Joffre et al., 2008; Tsang et al., 2008; Pilat et al., 2010). In contrast, when combined with bone-marrow transplantation, administration of a single dose of Treg fully prevented rejection of skin and heart (Joffre et al., 2008). Whereas Treg specific for directly presented donor-antigens allowed for survival of bone-marrow allografts, they failed to prevent chronic rejection of skin and heart. In contrast, Treg specific for indirectly presented donor-antigens fully prevented chronic heart and skin allograft rejection (Joffre et al., 2008). These results firmly demonstrated the clinical potential of Treg infusion in induction of bone-marrow chimerism and in the subsequent prevention of acute and chronic allograft rejection.

Figure 1. A regulatory T cell/hematopoietic chimerism-based protocol for induction of transplantation tolerance. (1) The allograft (e.g., heart) will be transplanted with concomitant infusion of donor BM or HSC into conditioned hosts. Rejection of the grafts will temporarily be prevented using an immunosuppressive regimen. (2) Donor (a) and host (b) BM will be cultured in vitro under conditions allowing for differentiation of DC. Host DC will be pulsed with donor antigen to assure indirect presentation of these antigens. Thus generated DC will then be co-cultured with host-derived Treg (c), allowing for expansion of Treg specific for directly and indirectly presented donor antigens. (3) Thus generated donor-antigen-specific Treg will then be infused into the host. Immunosuppression may temporarily be continued using drugs that do not affect Treg (e.g., Rapamycin). Using this protocol, full tolerance to donor-tissue will be achieved and chronic rejection effectively prevented.

Figure 2. Tolerance mechanisms induced by the proposed regulatory T cell/hematopoietic chimerism-based protocol for induction of transplantation tolerance. (1) Hematopoietic cells (e.g., DC) derived from the grafted BM will colonize the recipient’s thymus and induce deletion and anergy (i.e., “recessive tolerance”) of developing donor-specific host T lymphocytes. DC may also promote limited differentiation of donor-specific Treg that will contribute to transplantation tolerance. (2) Donor DC will also induce recessive tolerance of mature peripheral donor-specific T lymphocytes. These cells may, to a limited extent, directly induce donor-specific Treg. However, the dominant tolerance (i.e., Treg) induce by hematopoietic chimerism in (1) and (2) appears insufficient to durably prevent most notably chronic allograft rejection. (3) Infusion of donor-specific Treg will aid in engraftment of grafted donor BM/HSC (a) and inhibit the reactivity of mature peripheral donor-specific T lymphocytes (b), thus favoring graft-acceptance. They will also allow the differentiation of donor-specific conventional T lymphocytes into Treg (c), thus assuring persistence of tolerance and preventing chronic allograft rejection.

Treg and Hematopoietic Chimerism-Based Strategies: Some Limitations to Overcome

The data described above constitute a proof of principle that combining Treg and bone-marrow infusion can lead to subsequent tolerance to allogeneic tissues, even in very stringent donor/host combinations and for highly immunogenic tissues such as the skin. However, 5 Gy total body irradiation was required in that protocol (Joffre et al., 2008). This dose appears not suitable for clinical use as it is associated with severe temporary leukopenia. Interestingly, the group of Wekerle recently induced hematopoietic chimerism in mice using a comparable approach, but without or with very limited cytoreductive conditioning (Pilat et al., 2010, 2011). Treatment with costimulation-blocking agents, a short course of rapamycin, and injection of polyclonal Treg allowed for induction of hematopoietic chimerism. Skin grafts transplanted on these mice survived for more than 160 days, without signs of rejection or appearance of donor-specific antibodies (Pilat et al., 2010). More recently, this group raised similar conclusions using polyclonal host CD4+ lymphocytes previously transduced with a retroviral vector containing Foxp3 and a drug-free conditioning regimen where 1 Gy total body irradiation replaced the short course of rapamycin (Pilat et al., 2011). These protocols represent a major step forward to the clinic. However, they still rely on anti-CD154 treatment and this antibody is presently not usable in patients (see above). Different non-mutually exclusive strategies can be envisaged to avoid co-stimulatory-blockade. The use of hematopoietic or mesenchymal stem cells instead of bone-marrow cells could be an option, as this will significantly reduce the immunogenicity of the graft. Another strategy would be to improve the efficiency of the immunosuppression by injecting donor-specific Treg. Alloantigen-specific T cells survived longer and in several transplantation models gave substantially better results than polyclonal Tregs with irrelevant specificity (Joffre et al., 2004, 2008; Nishimura et al., 2004; Golshayan et al., 2007).

Another aspect that still needs to be tested before translating Treg-based strategies into the clinic is represented by the antigen-specificity of the treatments. Indeed, if Treg activation is antigen specific, these cells exert their suppressor effector function in a non-antigen-specific-manner in vitro (Thornton and Shevach, 2000). If true in vivo, infused Treg may therefore inhibit protective immunity. However, it has been shown that hematopoietic chimerism/Treg-based therapy against allograft rejection is (at least) donor specific. A related issue is that tolerance to donor-antigen may be broken by (e.g., viral) infection (Welsh et al., 2000; Williams et al., 2001; Forman et al., 2002). It therefore also needs to be verified to what extent Treg-based therapies are resistant to infection. Experimental work will need to be performed to clarify these important issues.

Finally, infused Treg do not necessarily survive indefinitely and tolerance may therefore wane away with time. In other transplantation models, however, it was shown that a tolerant T cell population can render naïve T cells tolerant and even tolerogenic (Waldmann, 2010). Very recently it was shown that this so-called “infectious tolerance” depends on Treg that induce novel Treg required for persistence of tolerance to allografts (Kendal et al., 2011). Even if it remains to be shown that also infused Treg can cause infectious tolerance, it appears therefore that Treg can induce life-long tolerance to allografts.

Conclusion

The data discussed here indicate that induction of persistent hematopoietic chimerism combined with infusion of Treg with appropriate specificity efficiently leads to life-long tolerance to allografts in experimental animal models (Figure 1). Thus, and not very surprisingly so, the mechanisms involved in the maintenance of tolerance to self antigens also appear required for tolerance to donor antigens (Figure 2). More work will need to be performed to establish conditioning regimens compatible with clinical constraints and to assess immunocompetence of grafted animals. The validity of these conclusions for non-human primates and humans remains to be studied. Very substantial progress has been made in recent years in the induction of authentic immunological tolerance to allogeneic organ grafts, and transplant recipients may soon be able to live a life free of the fear of losing the graft and of the severe side effects of immunosuppressive drugs.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Adams, A. B., Durham, M. M., Kean, L., Shirasugi, N., Ha, J., Williams, M. A., Rees, P. A., Cheung, M. C., Mittelstaedt, S., Bingaman, A. W., Archer, D. R., Pearson, T. C., Waller, E. K., and Larsen, C. P. (2001). Costimulation blockade, busulfan, and bone marrow promote titratable macrochimerism, induce transplantation tolerance, and correct genetic hemoglobinopathies with minimal myelosuppression. J. Immunol. 167, 1103–1111.

Alard, P., Matriano, J. A., Socarras, S., Ortega, M.-A., and Streilein, J. W. (1995). Detection of donor-derived cells by polymerase chain reaction in neonatally tolerant mice. Transplantation 60, 1125–1130.

Anderson, G., Partington, K. M., and Jenkinson, E. J. (1998). Differential effects of peptide diversity and stromal cell type in positive and negative selection in the thymus. J. Immunol. 161, 6599–6603.

Aschenbrenner, K., D’Cruz, L. M., Vollmann, E. H., Hinterberger, M., Emmerich, J., Swee, L. K., Rolink, A., and Klein, L. (2007). Selection of Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells specific for self antigen expressed and presented by Aire(+) medullary thymic epithelial cells. Nat. Immunol. 8, 351–358.

Baba, T., Nakamoto, Y., and Mukaida, N. (2009). Crucial contribution of thymic Sirp alpha+ conventional dendritic cells to central tolerance against blood-borne antigens in a CCR2-dependent manner. J. Immunol. 183, 3053–3063.

Barber, W. H., Mankin, J. A., Laskow, D. A., Deierhoi, M. H., Julian, B. A., Curtis, J. J., and Diethelm, A. G. (1991). Long-term results of a controlled prospective study with transfusion of donor-specific bone marrow in 57 cadaveric renal allograft recipients. Transplantation 51, 70–75.

Bensinger, S. J., Bandeira, A., Jordan, M. S., Caton, A. J., and Laufer, T. M. (2001). Major histocompatibility complex class II-positive cortical epithelium mediates the selection of CD4+25+ immunoregulatory T cells. J. Exp. Med. 194, 427–438.

Bigenzahn, S., Blaha, P., Koporc, Z., Pree, I., Selzer, E., Bergmeister, H., Wrba, F., Heusser, C., Wagner, K., Muehlbacher, F., and Wekerle, T. (2005). The role of non-deletional tolerance mechanisms in a murine model of mixed chimerism with costimulation blockade. Am. J. Transplant. 5, 1237–1247.

Billingham, R. E., Brent, L., and Medawar, P. B. (1953). Actively acquired tolerance of foreign cells. Nature 172, 603–606.

Billingham, R. E., Lampkin, G. H., Medawar, P. B., and Williams, H. L. L. (1952). Tolerance to homografts, twin diagnosis, and the freemartin condition in cattle. Heredity 6, 201–212.

Blom, D., Morrissey, N. J., Mesonero, C., Coppage, M., Fisher, T., Zuo, X. J., Jordan, S. C., and Orloff, M. S. (1996). Induction of specific tolerance through mixed hematopoietic chimerism prevents chronic renal allograft rejection in a rat model. Surgery 120, 213–219; discussion 219–220.

Boise, L. H., Minn, A. J., Noel, P. J., June, C. H., Accavitti, M. A., Lindsten, T., and Thompson, C. B. (1995). CD28 costimulation can promote T cell survival by enhancing the expression of Bcl-XL. Immunity 3, 87–98.

Bonasio, R., Scimone, M. L., Schaerli, P., Grabie, N., Lichtman, A. H., and von Andrian, U. H. (2006). Clonal deletion of thymocytes by circulating dendritic cells homing to the thymus. Nat. Immunol. 7, 1092–1100.

Boyse, E. A., Carswell, E. A., Scheid, M. P., and Old, L. J. (1973). Tolerance of Sk-incompatible skin grafts. Nature 244, 441–442.

Boyse, E. A., Lance, E. M., Carswell, E. A., Cooper, S., and Old, L. J. (1970). Rejection of skin allografts by radiation chimaeras: selective gene action in the specification of cell surface structure. Nature 227, 901–903.

Brocades Zaalberg, A., Vos, O., and Bekkum Van, D. W. (1957). Surviving rat skin grafts in mice. Nature 180, 238–239.

Brocker, T., Riedinger, M., and Karjalainen, K. (1997). Targeted expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules demonstrates that dendritic cells can induce negative but not positive selection of thymocytes in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 185, 541–550.

Buhler, L. H., Spitzer, T. R., Sykes, M., Sachs, D. H., Delmonico, F. L., Tolkoff-Rubin, N., Saidman, S. L., Sackstein, R., McAfee, S., Dey, B., Colby, C., and Cosimi, A. B. (2002). Induction of kidney allograft tolerance after transient lymphohematopoietic chimerism in patients with multiple myeloma and end-stage renal disease. Transplantation 74, 1405–1409.

Butcher, J. A., Hariharan, S., Adams, M. B., Johnson, C. P., Roza, A. M., and Cohen, E. P. (1999). Renal transplantation for end-stage renal disease following bone marrow transplantation: a report of six cases, with and without immunosuppression. Clin. Transplant. 13, 330–335.

Caridis, D. T., Liegeois, A., Barrett, I., and Monaco, A. P. (1973). Enhanced survival of canine renal allografts of ALS- treated dogs given bone marrow. Transplant. Proc. 5, 671–674.

Chai, J. G., Xue, S. A., Coe, D., Addey, C., Bartok, I., Scott, D., Simpson, E., Stauss, H. J., Hori, S., Sakaguchi, S., and Dyson, J. (2005). Regulatory T cells, derived from naive CD4+CD25- T cells by in vitro Foxp3 gene transfer, can induce transplantation tolerance. Transplantation 79, 1310–1316.

Colson, Y. L., Wren, S. M., Schuchert, M. J., Patrene, K. D., Johnson, P. C., Boggs, S. S., and Ildstad, S. T. (1995a). A nonlethal conditioning approach to achieve durable multilineage mixed chimerism and tolerance across major, minor, and hematopoietic histocompatibility barriers. J. Immunol. 155, 4179–4188.

Colson, Y. L., Zadach, K., Nalesnik, M., and Ildstad, S. T. (1995b). Mixed allogeneic chimerism in the rat. Donor-specific transplantation tolerance without chronic rejection for primarily vascularized cardiac allografts. Transplantation 60, 971–980.

Cosimi, A. B., and Sachs, D. H. (2004). Mixed chimerism and transplantation tolerance. Transplantation 77, 943–946.

Crowe, J. E. Jr., Sannella, E. C., Pfeiffer, S., Zorn, G. L., Azimzadeh, A., Newman, R., Miller, G. G., and Pierson, R. N. (2003). CD154 regulates primate humoral immunity to influenza. Am. J. Transplant. 3, 680–688.

Domenig, C., Sanchez-Fueyo, A., Kurtz, J., Alexopoulos, S. P., Mariat, C., Sykes, M., Strom, T. B., and Zheng, X. X. (2005). Roles of deletion and regulation in creating mixed chimerism and allograft tolerance using a nonlymphoablative irradiation-free protocol. J. Immunol. 175, 51–60.

Donckier, V., Troisi, R., Toungouz, M., Colle, I., Van Vlierberghe, H., Jacquy, C., Martiat, P., Stordeur, P., Zhou, L., Boon, N., Lambermont, M., Schandene, L., Van Laethem, J. L., Noens, L., Gelin, M., de Hemptinne, B., and Goldman, M. (2004). Donor stem cell infusion after non-myeloablative conditioning for tolerance induction to HLA mismatched adult living-donor liver graft. Transpl. Immunol. 13, 139–146.

Donckier, V., Wissing, M., Bruyns, C., Abramowicz, D., Lybin, M., Vanderhaeghen, M. L., and Goldman, M. (1995). Critical role of interleukin 4 in the induction of neonatal transplantation tolerance. Transplantation 59, 1571–1576.

Emery, D., and McCullagh, P. (1980). Immunological reactivity between chimeric cattle twins. I. Homograft reaction. Transplantation 29, 4–9.

Eto, M., Mayumi, H., Tomita, Y., Yoshikai, Y., and Nomoto, K. (1990). Intrathymic clonal deletion of V beta 6+ T cells in cyclophosphamide-induced tolerance to H-2-compatible, Mls-disparate antigens. J. Exp. Med. 171, 97–113.

Fehr, T., Haspot, F., Mollov, J., Chittenden, M., Hogan, T., and Sykes, M. (2008a). Alloreactive CD8 T cell tolerance requires recipient B cells, dendritic cells, and MHC class II. J. Immunol. 181, 165–173.

Fehr, T., Wang, S., Haspot, F., Kurtz, J., Blaha, P., Hogan, T., Chittenden, M., Wekerle, T., and Sykes, M. (2008b). Rapid deletional peripheral CD8 T cell tolerance induced by allogeneic bone marrow: role of donor class II MHC and B cells. J. Immunol. 181, 4371–4380.

Fontenot, J. D., and Rudensky, A. Y. (2005). A well adapted regulatory contrivance: regulatory T cell development and the forkhead family transcription factor Foxp3. Nat. Immunol. 6, 331–337.

Forman, D., Welsh, R. M., Markees, T. G., Woda, B. A., Mordes, J. P., Rossini, A. A., and Greiner, D. L. (2002). Viral abrogation of stem cell transplantation tolerance causes graft rejection and host death by different mechanisms. J. Immunol. 168, 6047–6056.

Fuchimoto, Y., Huang, C. A., Yamada, K., Gleit, Z. L., Kitamura, H., Griesemer, A., Scheier-Dolberg, R., Melendy, E., White-Scharf, M. E., and Sachs, D. H. (2001). Induction of kidney allograft tolerance through mixed chimerism in miniature swine. Transplant. Proc. 33, 77.

Fuchimoto, Y., Huang, C. A., Yamada, K., Shimizu, A., Kitamura, H., Colvin, R. B., Ferrara, V., Murphy, M. C., Sykes, M., White-Scharf, M., Neville, D. M. Jr., and Sachs, D. H. (2000). Mixed chimerism and tolerance without whole body irradiation in a large animal model. J. Clin. Invest. 105, 1779–1789.

Fudaba, Y., Spitzer, T. R., Shaffer, J., Kawai, T., Fehr, T., Delmonico, F., Preffer, F., Tolkoff-Rubin, N., Dey, B. R., Saidman, S. L., Kraus, A., Bonnefoix, T., McAfee, S., Power, K., Kattleman, K., Colvin, R. B., Sachs, D. H., Cosimi, A. B., and Sykes, M. (2006). Myeloma responses and tolerance following combined kidney and nonmyeloablative marrow transplantation: in vivo and in vitro analyses. Am. J. Transplant. 6, 2121–2133.

Fujisaki, J., Wu, J., Carlson, A. L., Silberstein, L., Putheti, P., Larocca, R., Gao, W., Saito, T. I., Lo Celso, C., Tsuyuzaki, H., Sato, T., Cote, D., Sykes, M., Strom, T. B., Scadden, D. T., and Lin, C. P. (2011). In vivo imaging of Treg cells providing immune privilege to the haematopoietic stem-cell niche. Nature 474, 216–219.

Golshayan, D., Jiang, S., Tsang, J., Garin, M. I., Mottet, C., and Lechler, R. I. (2007). In vitro-expanded donor alloantigen-specific CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells promote experimental transplantation tolerance. Blood 109, 827–835.

Guo, Z., Wang, J., Dong, Y., Adams, A. B., Shirasugi, N., Kim, O., Hart, J., Newton-West, M., Pearson, T. C., Larsen, C. P., and Newell, K. A. (2003). Long-term survival of intestinal allografts induced by costimulation blockade, busulfan and donor bone marrow infusion. Am. J. Transplant. 3, 1091–1098.

Guzzetta, P. C., Sundt, T. M., Suzuki, T., Mixon, A., Rosengard, B. R., and Sachs, D. H. (1991). Induction of kidney transplantation tolerance across major histocompatibility complex barriers by bone marrow transplantation in miniature swine. Transplantation 51, 862–866.

Hanash, A. M., and Levy, R. B. (2005). Donor CD4+CD25+ T cells promote engraftment and tolerance following MHC-mismatched hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood 105, 1828–1836.

Hartner, W. C., De Fazio, S. R., Maki, T., Markees, T. G., Monaco, A. P., and Gozzo, J. J. (1986). Prolongation of renal allograft survival in antilymphocyte-serum-treated dogs by postoperative injection of density-gradient-fractionated donor bone marrow. Transplantation 42, 593–597.

Hawiger, D., Inaba, K., Dorsett, Y., Guo, M., Mahnke, K., Rivera, M., Ravetch, J. V., Steinman, R. M., and Nussenzweig, M. C. (2001). Dendritic cells induce peripheral T cell unresponsiveness under steady state conditions in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 194, 769–779.

Henn, V., Slupsky, J. R., Grafe, M., Anagnostopoulos, I., Forster, R., Muller-Berghaus, G., and Kroczek, R. A. (1998). CD40 ligand on activated platelets triggers an inflammatory reaction of endothelial cells. Nature 391, 591–594.

Hogquist, K. A., Baldwin, T. A., and Jameson, S. C. (2005). Central tolerance: learning self-control in the thymus. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 5, 772–782.

Horner, B. M., Cina, R. A., Wikiel, K. J., Lima, B., Ghazi, A., Lo, D. P., Yamada, K., Sachs, D. H., and Huang, C. A. (2006). Predictors of organ allograft tolerance following hematopoietic cell transplantation. Am. J. Transplant. 6, 2894–2902.

Hsieh, C. S., Liang, Y., Tyznik, A. J., Self, S. G., Liggitt, D., and Rudensky, A. Y. (2004). Recognition of the peripheral self by naturally arising CD25+ CD4+ T cell receptors. Immunity 21, 267–277.

Huang, C. A., Fuchimoto, Y., Scheier-Dolberg, R., Murphy, M. C., Neville, D. M. Jr., and Sachs, D. H. (2000). Stable mixed chimerism and tolerance using a nonmyeloablative preparative regimen in a large-animal model. J. Clin. Invest. 105, 173–181.

Hudrisier, D., Feau, S., Bonnet, V., Romagnoli, P., and van Meerwijk, J. P. M. (2003). In vivo unresponsiveness of T lymphocyte induced by thymic medullary epithelium requires antigen presentation by radioresistant cells. Immunology 108, 24–31.

Ildstad, S. T., and Sachs, D. H. (1984). Reconstitution with syngeneic plus allogeneic or xenogeneic bone marrow leads to specific acceptance of allografts or xenografts. Nature 307, 168–170.

Issa, F., and Wood, K. J. (2010). CD4+ regulatory T cells in solid organ transplantation. Curr. Opin. Organ. Transplant.

Iwai, T., Tomita, Y., Okano, S., Shimizu, I., Yasunami, Y., Kajiwara, T., Yoshikai, Y., Taniguchi, M., Nomoto, K., and Yasui, H. (2006). Regulatory roles of NKT cells in the induction and maintenance of cyclophosphamide-induced tolerance. J. Immunol. 177, 8400–8409.

Jenkinson, E. J., Anderson, G., and Owen, J. J. (1992). Studies on T cell maturation on defined thymic stromal cell populations in vitro. J. Exp. Med. 176, 845–853.

Joffre, O., Gorsse, N., Romagnoli, P., Hudrisier, D., and van Meerwijk, J. P. M. (2004). Induction of antigen-specific tolerance to bone marrow allografts with CD4+CD25+ T lymphocytes. Blood 103, 4216–4221.

Joffre, O., Santolaria, T., Calise, D., Al Saati, T., Hudrisier, D., Romagnoli, P., and van Meerwijk, J. P. M. (2008). Prevention of acute and chronic allograft rejection with CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T lymphocytes. Nat. Med. 14, 88–92.

Joffre, O., and van Meerwijk, J. P. M. (2006). CD4+CD25+ regulatory T lymphocytes in bone marrow transplantation. Semin. Immunol. 18, 128–135.

Ju, S. T., Panka, D. J., Cui, H., Ettinger, R., el-Khatib, M., Sherr, D. H., Stanger, B. Z., and Marshak-Rothstein, A. (1995). Fas(CD95)/FasL interactions required for programmed cell death after T-cell activation. Nature 373, 444–448.

Kahan, B. D. (2003). Individuality: the barrier to optimal immunosuppression. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3, 831–838.

Kappler, J. W., Roehm, N., and Marrack, P. (1987a). T cell tolerance by clonal elimination in the thymus. Cell 49, 273–280.

Kappler, J. W., Wade, T., White, J., Kushnir, E., Blackman, M., Bill, J., Roehm, N., and Marrack, P. (1987b). A T cell receptor V beta segment that imparts reactivity to a class II major histocompatibility complex product. Cell 49, 263–271.

Kappler, J. W., Staerz, U., White, J., and Marrack, P. C. (1988). Self-tolerance eliminates T cells specific for Mls-modified products of the major histocompatibility complex. Nature 332, 35–40.

Karim, M., Feng, G., Wood, K. J., and Bushell, A. R. (2005). CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cells generated by exposure to a model protein antigen prevent allograft rejection: antigen-specific reactivation in vivo is critical for bystander regulation. Blood 105, 4871–4877.

Kawai, T., Andrews, D., Colvin, R. B., Sachs, D. H., and Cosimi, A. B. (2000). Thromboembolic complications after treatment with monoclonal antibody against CD40 ligand. Nat. Med. 6, 114.

Kawai, T., Cosimi, A. B., Colvin, R. B., Powelson, J., Eason, J., Kozlowski, T., Sykes, M., Monroy, R., Tanaka, M., and Sachs, D. H. (1995). Mixed allogeneic chimerism and renal allograft tolerance in cynomolgus monkeys. Transplantation 59, 256–262.

Kawai, T., Cosimi, A. B., Spitzer, T. R., Tolkoff-Rubin, N., Suthanthiran, M., Saidman, S. L., Shaffer, J., Preffer, F. I., Ding, R., Sharma, V., Fishman, J. A., Dey, B., Ko, D. S., Hertl, M., Goes, N. B., Wong, W., Williams, W. W. Jr., Colvin, R. B., Sykes, M., and Sachs, D. H. (2008). HLA-mismatched renal transplantation without maintenance immunosuppression. N. Engl. J. Med. 358, 353–361.

Kawai, T., Cosimi, A. B., Wee, S. L., Houser, S., Andrews, D., Sogawa, H., Phelan, J., Boskovic, S., Nadazdin, O., Abrahamian, G., Colvin, R. B., Sachs, D. H., and Madsen, J. C. (2002). Effect of mixed hematopoietic chimerism on cardiac allograft survival in cynomolgus monkeys. Transplantation 73, 1757–1764.

Kawai, T., Poncelet, A., Sachs, D. H., Mauiyyedi, S., Boskovic, S., Wee, S. L., Ko, D. S., Bartholomew, A., Kimikawa, M., Hong, H. Z., Abrahamian, G., Colvin, R. B., and Cosimi, A. B. (1999). Long-term outcome and alloantibody production in a non-myeloablative regimen for induction of renal allograft tolerance. Transplantation 68, 1767–1775.

Kawai, T., Sogawa, H., Boskovic, S., Abrahamian, G., Smith, R. N., Wee, S. L., Andrews, D., Nadazdin, O., Koyama, I., Sykes, M., Winn, H. J., Colvin, R. B., Sachs, D. H., and Cosimi, A. B. (2004). CD154 blockade for induction of mixed chimerism and prolonged renal allograft survival in nonhuman primates. Am. J. Transplant. 4, 1391–1398.

Kendal, A. R., Chen, Y., Regateiro, F. S., Ma, J., Adams, E., Cobbold, S. P., Hori, S., and Waldmann, H. (2011). Sustained suppression by Foxp3+ regulatory T cells is vital for infectious transplantation tolerance. J. Exp. Med. 208, 2043–2053.

Khan, A., Tomita, Y., and Sykes, M. (1996). Thymic dependence of loss of tolerance in mixed allogeneic bone marrow chimeras after depletion of donor antigen. Peripheral mechanisms do not contribute to maintenance of tolerance. Transplantation 62, 380–387.

Kimikawa, M., Kawai, T., Sachs, D. H., Colvin, R. B., Bartholomew, A., and Cosimi, A. B. (1997a). Mixed chimerism and transplantation tolerance induced by a nonlethal preparative regimen in cynomolgus monkeys. Transplant. Proc. 29, 1218.

Kimikawa, M., Sachs, D. H., Colvin, R. B., Bartholomew, A., Kawai, T., and Cosimi, A. B. (1997b). Modifications of the conditioning regimen for achieving mixed chimerism and donor-specific tolerance in cynomolgus monkeys. Transplantation 64, 709–716.

Kleindienst, P., Chretien, I., Winkler, T., and Brocker, T. (2000). Functional comparison of thymic B cells and dendritic cells in vivo. Blood 95, 2610–2616.

Koyama, I., Kawai, T., Andrews, D., Boskovic, S., Nadazdin, O., Wee, S. L., Sogawa, H., Wu, D. L., Smith, R. N., Colvin, R. B., Sachs, D. H., and Cosimi, A. B. (2004). Thrombophilia associated with anti-CD154 monoclonal antibody treatment and its prophylaxis in nonhuman primates. Transplantation 77, 460–462.

Kurtz, J., Shaffer, J., Lie, A., Anosova, N., Benichou, G., and Sykes, M. (2004). Mechanisms of early peripheral CD4 T-cell tolerance induction by anti-CD154 monoclonal antibody and allogeneic bone marrow transplantation: evidence for anergy and deletion but not regulatory cells. Blood 103, 4336–4343.

Larsen, C. P., Elwood, E. T., Alexander, D. Z., Ritchie, S. C., Hendrix, R., Tucker-Burden, C., Cho, H. R., Aruffo, A., Hollenbaugh, D., Linsley, P. S., Winn, K. J., and Pearson, T. C. (1996). Long-term acceptance of skin and cardiac allografts after blocking CD40 and CD28 pathways. Nature 381, 434–438.

Le Douarin, N., Corbel, C., Bandeira, A., Thomas-Vaslin, V., Modigliani, Y., Coutinho, A., and Salaun, J. (1996). Evidence for a thymus-dependent form of tolerance that is not based on elimination or anergy of reactive T cells. Immunol. Rev. 149, 35–53.

Lenardo, M. J. (1991). Interleukin-2 programs mouse alpha beta T lymphocytes for apoptosis. Nature 353, 858–861.

Li, X. C., and Turka, L. A. (2010). An update on regulatory T cells in transplant tolerance and rejection. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 6, 577–583.

Lubaroff, D. M., and Silvers, W. K. (1973). The importance of chimerism in maintaining tolerance of skin allografts in mice. J. Immunol. 111, 65–71.

Luo, B., Chan, W. F., Shapiro, A. M., and Anderson, C. C. (2007). Non-myeloablative mixed chimerism approaches and tolerance, a split decision. Eur. J. Immunol. 37, 1233–1242.

Luo, B., Nanji, S. A., Schur, C. D., Pawlick, R. L., Anderson, C. C., and Shapiro, A. M. (2005). Robust tolerance to fully allogeneic islet transplants achieved by chimerism with minimal conditioning. Transplantation 80, 370–377.

Luther, S. A., and Acha-Orbea, H. (1997). Mouse mammary tumor virus: immunological interplays between virus and host. Adv. Immunol. 65, 139–243.

MacDonald, H. R., Pedrazzini, T., Schneider, R., Louis, J. A., Zinkernagel, R. M., and Hengartner, H. (1988a). Intrathymic elimination of Mlsa-reactive (V beta 6+) cells during neonatal tolerance induction to Mlsa-encoded antigens. J. Exp. Med. 167, 2005–2010.

MacDonald, H. R., Schneider, R., Lees, R. K., Howe, R. C., Acha-Orbea, H., Festenstein, H., Zinkernagel, R. M., and Hengartner, H. (1988b). T-cell receptor V beta use predicts reactivity and tolerance to Mlsa-encoded antigens. Nature 332, 40–45.

Madsen, J. C., Yamada, K., Allan, J. S., Choo, J. K., Erhorn, A. E., Pins, M. R., Vesga, L., Slisz, J. K., and Sachs, D. H. (1998). Transplantation tolerance prevents cardiac allograft vasculopathy in major histocompatibility complex class I-disparate miniature swine. Transplantation 65, 304–313.

Main, J. M., and Prehn, R. T. (1955). Successful skin homografts after the administration of high dosage X radiation and homologous bone marrow. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 15, 1023–1029.

Manilay, J. O., Pearson, D. A., Sergio, J. J., Swenson, K. G., and Sykes, M. (1998). Intrathymic deletion of alloreactive T cells in mixed bone marrow chimeras prepared with a nonmyeloablative conditioning regimen. Transplantation 66, 96–102.

Mapara, M. Y., Pelot, M., Zhao, G., Swenson, K., Pearson, D., and Sykes, M. (2001). Induction of stable long-term mixed hematopoietic chimerism following nonmyeloablative conditioning with T cell-depleting antibodies, cyclophosphamide, and thymic irradiation leads to donor-specific in vitro and in vivo tolerance. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 7, 646–655.

Matzinger, P., and Guerder, S. (1989). Does T-cell tolerance require a dedicated antigen-presenting cell? Nature 338, 74–76.

Mayumi, H., and Good, R. A. (1989). Long-lasting skin allograft tolerance in adult mice induced across fully allogeneic (multimajor H-2 plus multiminor histocompatibility) antigen barriers by a tolerance-inducing method using cyclophosphamide. J. Exp. Med. 169, 213–238.

McDaniel, D. O., Naftilan, J., Hulvey, K., Shaneyfelt, S., Lemons, J. A., Lagoo-Deenadayalan, S., Hudson, S., Diethelm, A. G., and Barber, W. H. (1994). Peripheral blood chimerism in renal allograft recipients transfused with donor bone marrow. Transplantation 57, 852–856.

Meier-Kriesche, H. U., and Kaplan, B. (2011). The search for CNI-free immunosuppression: no free lunch. Am. J. Transplant. 11, 1355–1356.

Metzler, B., Gfeller, P., Bigaud, M., Li, J., Wieczorek, G., Heusser, C., Lake, P., and Katopodis, A. (2004). Combinations of anti-LFA-1, everolimus, anti-CD40 ligand, and allogeneic bone marrow induce central transplantation tolerance through hemopoietic chimerism, including protection from chronic heart allograft rejection. J. Immunol. 173, 7025–7036.

Mezrich, J. D., Kesselheim, J. A., Johnston, D. R., Yamada, K., Sachs, D. H., and Madsen, J. C. (2003a). The role of regulatory cells in miniature swine rendered tolerant to cardiac allografts by donor kidney cotransplantation. Am. J. Transplant. 3, 1107–1115.

Mezrich, J. D., Yamada, K., Lee, R. S., Mawulawde, K., Benjamin, L. C., Schwarze, M. L., Maloney, M. E., Amoah, H. C., Houser, S. L., Sachs, D. H., and Madsen, J. C. (2003b). Induction of tolerance to heart transplants by simultaneous cotransplantation of donor kidneys may depend on a radiation-sensitive renal-cell population. Transplantation 76, 625–631.

Mineo, D., Ricordi, C., Xu, X., Pileggi, A., Garcia-Morales, R., Khan, A., Baidal, D. A., Han, D., Monroy, K., Miller, J., Pugliese, A., Froud, T., Inverardi, L., Kenyon, N. S., and Alejandro, R. (2008). Combined islet and hematopoietic stem cell allotransplantation: a clinical pilot trial to induce chimerism and graft tolerance. Am. J. Transplant. 8, 1262–1274.

Monaco, A. P. (2003). Chimerism in organ transplantation: conflicting experiments and clinical observations. Transplantation 75, 13S–16S.

Nadig, S. N., Wieckiewicz, J., Wu, D. C., Warnecke, G., Zhang, W., Luo, S., Schiopu, A., Taggart, D. P., and Wood, K. J. (2010). In vivo prevention of transplant arteriosclerosis by ex vivo-expanded human regulatory T cells. Nat. Med. 16, 809–813.

Nishimura, E., Sakihama, T., Setoguchi, R., Tanaka, K., and Sakaguchi, S. (2004). Induction of antigen-specific immunologic tolerance by in vivo and in vitro antigen-specific expansion of naturally arising Foxp3+CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cells. Int. Immunol. 16, 1189–1201.

Orloff, M. S., DeMara, E. M., Coppage, M. L., Leong, N., Fallon, M. A., Sickel, J., Zuo, X. J., Prehn, J., and Jordan, S. C. (1995). Prevention of chronic rejection and graft arteriosclerosis by tolerance induction. Transplantation 59, 282–288.

Owen, R. D. (1945). Immunogenic consequences of vascular anastomoses between bovine twins. Science 102, 400–401.

Pearson, T. C., Madsen, J. C., Larsen, C. P., Morris, P. J., and Wood, K. J. (1992). Induction of transplantation tolerance in adults using donor antigen and anti-CD4 monoclonal antibody. Transplantation 54, 475–483.

Pilat, N., Baranyi, U., Klaus, C., Jaeckel, E., Mpofu, N., Wrba, F., Golshayan, D., Muehlbacher, F., and Wekerle, T. (2010). Treg-therapy allows mixed chimerism and transplantation tolerance without cytoreductive conditioning. Am. J. Transplant. 10, 751–762.

Pilat, N., Klaus, C., Gattringer, M., Jaeckel, E., Wrba, F., Golshayan, D., Baranyi, U., and Wekerle, T. (2011). Therapeutic efficacy of polyclonal tregs does not require rapamycin in a low-dose irradiation bone marrow transplantation model. Transplantation 92, 280–288.

Pircher, H., Brduscha, K., Steinhoff, U., Kasai, M., Mizuochi, T., Zinkernagel, R. M., Hengartner, H., Kyewski, B., and Muller, K. P. (1993). Tolerance induction by clonal deletion of CD4+8+thymocytes in vitro does not require dedicated antigen-presenting cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 23, 669–674.

Pircher, H., Muller, K. P., Kyewski, B. A., and Hengartner, H. (1992). Thymocytes can tolerize thymocytes by clonal deletion in vitro. Int. Immunol. 4, 1065–1069.

Porcheray, F., Wong, W., Saidman, S. L., De Vito, J., Girouard, T. C., Chittenden, M., Shaffer, J., Tolkoff-Rubin, N., Dey, B. R., Spitzer, T. R., Colvin, R. B., Cosimi, A. B., Kawai, T., Sachs, D. H., Sykes, M., and Zorn, E. (2009). B-cell immunity in the context of T-cell tolerance after combined kidney and bone marrow transplantation in humans. Am. J. Transplant. 9, 2126–2135.

Proietto, A. I., van Dommelen, S., Zhou, P., Rizzitelli, A., D’Amico, A., Steptoe, R. J., Naik, S. H., Lahoud, M. H., Liu, Y., Zheng, P., Shortman, K., and Wu, L. (2008). Dendritic cells in the thymus contribute to T-regulatory cell induction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 19869–19874.

Qin, S. X., Wise, M., Cobbold, S. P., Leong, L., Kong, Y. C., Parnes, J. R., and Waldmann, H. (1990). Induction of tolerance in peripheral T cells with monoclonal antibodies. Eur. J. Immunol. 20, 2737–2745.

Rammensee, H. G., Kroschewski, R., and Frangoulis, B. (1989). Clonal anergy induced in mature V beta 6+ T lymphocytes on immunizing Mls-1b mice with Mls-1a expressing cells. Nature 339, 541–544.

Ribot, J., Enault, G., Pilipenko, S., Huchenq, A., Calise, M., Hudrisier, D., Romagnoli, P., and van Meerwijk, J. P. M. (2007). Shaping of the autoreactive regulatory T cell repertoire by thymic cortical positive selection. J. Immunol. 179, 6741–6748.

Ribot, J., Romagnoli, P., and van Meerwijk, J. P. M. (2006). Agonist ligands expressed by thymic epithelium enhance positive selection of regulatory T lymphocytes from precursors with a normally diverse TCR repertoire. J. Immunol. 177, 1101–1107.

Rocken, M. (1996). Immune deviation–the third dimension of nondeletional T cell tolerance. Immunol. Rev. 149, 175–194.

Romagnoli, P., Hudrisier, D., and van Meerwijk, J. P. M. (2002). Preferential recognition of self-antigens despite normal thymic deletion of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. J. Immunol. 168, 1644–1648.

Romagnoli, P., Hudrisier, D., and van Meerwijk, J. P. M. (2005). Molecular signature of recent thymic selection events on effector and regulatory CD4+ T lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 175, 5751–5758.

Romagnoli, P., Ribot, J., Tellier, J., and van Meerwijk, J. P. M. (2008). “Thymic and peripheral generation of CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells,” in Regulatory T cells and Clinical Application, ed. S. Jiang (Springer Science+Business Media), 29–55.

Russell, J. H. (1995). Activation-induced death of mature T cells in the regulation of immune responses. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 7, 382–388.

Russell, P. S., Chase, C. M., Sykes, M., Ito, H., Shaffer, J., and Colvin, R. B. (2001). Tolerance, mixed chimerism, and chronic transplant arteriopathy. J. Immunol. 167, 5731–5740.

Sakaguchi, S., Ono, M., Setoguchi, R., Yagi, H., Hori, S., Fehervari, Z., Shimizu, J., Takahashi, T., and Nomura, T. (2006). Foxp3+ CD25+ CD4+ natural regulatory T cells in dominant self-tolerance and autoimmune disease. Immunol. Rev. 212, 8–27.

Sakaguchi, S., Sakaguchi, N., Asano, M., Itoh, M., and Toda, M. (1995). Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by activated T cells expressing IL-2 receptor alpha-chains (CD25). Breakdown of a single mechanism of self-tolerance causes various autoimmune diseases. J. Immunol. 155, 1151–1164.

Scandling, J. D., Busque, S., Dejbakhsh-Jones, S., Benike, C., Millan, M. T., Shizuru, J. A., Hoppe, R. T., Lowsky, R., Engleman, E. G., and Strober, S. (2008). Tolerance and chimerism after renal and hematopoietic-cell transplantation. N. Engl. J. Med. 358, 362–368.

Scheid, M., Boyse, E. A., Carswell, E. A., and Old, L. J. (1972). Serologically demonstrable alloantigens of mouse epidermal cells. J. Exp. Med. 135, 938–955.

Shevach, E. M., DiPaolo, R. A., Andersson, J., Zhao, D. M., Stephens, G. L., and Thornton, A. M. (2006). The lifestyle of naturally occurring CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Immunol. Rev. 212, 60–73.

Shirasugi, N., Adams, A. B., Durham, M. M., Lukacher, A. E., Xu, H., Rees, P., Cowan, S. R., Williams, M. A., Pearson, T. C., and Larsen, C. P. (2002). Prevention of chronic rejection in murine cardiac allografts: a comparison of chimerism- and nonchimerism-inducing costimulation blockade-based tolerance induction regimens. J. Immunol. 169, 2677–2684.

Slavin, S., Reitz, B., Bieber, C. P., Kaplan, H. S., and Strober, S. (1978). Transplantation tolerance in adult rats using total lymphoid irradiation: permanent survival of skin, heart, and marrow allografts. J. Exp. Med. 147, 700–707.

Slupsky, J. R., Kalbas, M., Willuweit, A., Henn, V., Kroczek, R. A., and Muller-Berghaus, G. (1998). Activated platelets induce tissue factor expression on human umbilical vein endothelial cells by ligation of CD40. Thromb. Haemost. 80, 1008–1014.

Sorof, J. M., Koerper, M. A., Portale, A. A., Potter, D., DeSantes, K., and Cowan, M. (1995). Renal transplantation without chronic immunosuppression after T cell-depleted, HLA-mismatched bone marrow transplantation. Transplantation 59, 1633–1635.

Spitzer, T. R., Delmonico, F., Tolkoff-Rubin, N., McAfee, S., Sackstein, R., Saidman, S., Colby, C., Sykes, M., Sachs, D. H., and Cosimi, A. B. (1999). Combined histocompatibility leukocyte antigen-matched donor bone marrow and renal transplantation for multiple myeloma with end stage renal disease: the induction of allograft tolerance through mixed lymphohematopoietic chimerism. Transplantation 68, 480–484.

Steinmuller, D., and Lofgreen, J. S. (1974). Differential survival of skin and heart allografts in radiation chimaeras provides further evidence for Sk histocompatibility antigen. Nature 248, 796–797.

Stone, W. H., Cragle, R. G., Johnson, D. F., Bacon, J. A., Bendel, S., and Korda, N. (1971). Long-term observations of skin grafts between chimeric cattle twins. Transplantation 12, 421–428.

Stone, W. H., Cragle, R. G., Swanson, E. W., and Brown, D. G. (1965). Skin grafts: delayed rejection between pairs of cattle twins showing erythrocyte chimerism. Science 148, 1335–1336.

Streilein, J. W. (1991). Neonatal tolerance of H-2 alloantigens. Procuring graft acceptance the “old-fashioned” way. Transplantation 52, 1–10.

Streilein, J. W., and Klein, J. (1977). Neonatal tolerance induction across regions of H-2 complex. J. Immunol. 119, 2147–2150.

Strober, S., Modry, D. L., Hoppe, R. T., Pennock, J. L., Bieber, C. P., Holm, B. I., Jamieson, S. W., Stinson, E. B., Schroder, J., and Suomalainen, H. (1984). Induction of specific unresponsiveness to heart allografts in mongrel dogs treated with total lymphoid irradiation and antithymocyte globulin. J. Immunol. 132, 1013–1018.

Thomas, J., Carver, M., Cunningham, P., Park, K., Gonder, J., and Thomas, F. (1987). Promotion of incompatible allograft acceptance in rhesus monkeys given posttransplant antithymocyte globulin and donor bone marrow. I. In vivo parameters and immunohistologic evidence suggesting microchimerism. Transplantation 43, 332–338.

Thomas, J. M., Carver, F. M., Foil, M. B., Hall, W. R., Adams, C., Fahrenbruch, G. B., and Thomas, F. T. (1983). Renal allograft tolerance induced with ATG and donor bone marrow in outbred rhesus monkeys. Transplantation 36, 104–106.

Thornton, A. M., and Shevach, E. M. (2000). Suppressor effector function of CD4+CD25+ immunoregulatory T cells is antigen nonspecific. J. Immunol. 164, 183–190.

Tomita, Y., Khan, A., and Sykes, M. (1994). Role of intrathymic clonal deletion and peripheral anergy in transplantation tolerance induced by bone marrow transplantation in mice conditioned with a nonmyeloablative regimen. J. Immunol. 153, 1087–1098.

Tomita, Y., Mayumi, H., Eto, M., and Nomoto, K. (1990a). Importance of suppressor T cells in cyclophosphamide-induced tolerance to the non-H-2-encoded alloantigens. Is mixed chimerism really required in maintaining a skin allograft tolerance? J. Immunol. 144, 463–473.

Tomita, Y., Nishimura, Y., Harada, N., Eto, M., Ayukawa, K., Yoshikai, Y., and Nomoto, K. (1990b). Evidence for involvement of clonal anergy in MHC class I and class II disparate skin allograft tolerance after the termination of intrathymic clonal deletion. J. Immunol. 145, 4026–4036.

Trentin, J. J. (1956). Mortality and skin transplantability in x-irradiated mice receiving isologous, homologous or heterologous bone marrow. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 92, 688–693.

Tsang, J. Y., Tanriver, Y., Jiang, S., Xue, S. A., Ratnasothy, K., Chen, D., Stauss, H. J., Bucy, R. P., Lombardi, G., and Lechler, R. (2008). Conferring indirect allospecificity on CD4CD25 Tregs by TCR gene transfer favors transplantation tolerance in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 118, 3619–3628.

van Meerwijk, J. P. M., and MacDonald, H. R. (1999). In vivo T lymphocyte tolerance in the absence of thymic clonal deletion mediated by haematopoietic cells. Blood 93, 3856–3862.

Van Parijs, L., Ibraghimov, A., and Abbas, A. K. (1996). The roles of costimulation and Fas in T cell apoptosis and peripheral tolerance. Immunity 4, 321–328.

Walker, L. S., and Abbas, A. K. (2002). The enemy within: keeping self-reactive T cells at bay in the periphery. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2, 11–19.

Watanabe, N., Wang, Y. H., Lee, H. K., Ito, T., Wang, Y. H., Cao, W., and Liu, Y. J. (2005). Hassall’s corpuscles instruct dendritic cells to induce CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in human thymus. Nature 436, 1181–1185.

Wekerle, T., Kurtz, J., Ito, H., Ronquillo, J. V., Dong, V., Zhao, G., Shaffer, J., Sayegh, M. H., and Sykes, M. (2000). Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation with co-stimulatory blockade induces macrochimerism and tolerance without cytoreductive host treatment. Nat. Med. 6, 464–469.

Wekerle, T., Kurtz, J., Sayegh, M., Ito, H., Wells, A., Bensinger, S., Shaffer, J., Turka, L., and Sykes, M. (2001). Peripheral deletion after bone marrow transplantation with costimulatory blockade has features of both activation-induced cell death and passive cell death. J. Immunol. 166, 2311–2316.

Wekerle, T., Sayegh, M. H., Hill, J., Zhao, Y., Chandraker, A., Swenson, K. G., Zhao, G., and Sykes, M. (1998). Extrathymic T cell deletion and allogeneic stem cell engraftment induced with costimulatory blockade is followed by central T cell tolerance. J. Exp. Med. 187, 2037–2044.

Wekerle, T., and Sykes, M. (1999). Mixed chimerism as an approach for the induction of transplantation tolerance. Transplantation 68, 459–467.

Welsh, R. M., Markees, T. G., Woda, B. A., Daniels, K. A., Brehm, M. A., Mordes, J. P., Greiner, D. L., and Rossini, A. A. (2000). Virus-induced abrogation of transplantation tolerance induced by donor-specific transfusion and anti-CD154 antibody. J. Virol. 74, 2210–2218.

Williams, M. A., Tan, J. T., Adams, A. B., Durham, M. M., Shirasugi, N., Whitmire, J. K., Harrington, L. E., Ahmed, R., Pearson, T. C., and Larsen, C. P. (2001). Characterization of virus-mediated inhibition of mixed chimerism and allospecific tolerance. J. Immunol. 167, 4987–4995.

Wirnsberger, G., Mair, F., and Klein, L. (2009). Regulatory T cells differentiation of thymocytes does not require a dedicated antigen-presenting cell but is under T cell-intrinsic developmental control. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. doi:10.1073/pnas.0901877106.

Wood, P. J., and Streilein, J. W. (1982). Ontogeny of acquired immunological tolerance to H-2 alloantigens. Eur. J. Immunol. 12, 188–194.

Wren, S. M., Hronakes, M. L., and Ildstad, S. T. (1993). CD4+ T cells, but not CD8+ T cells, mediate the breaking of tolerance in mixed allogeneic chimeras (B10 + B10.BR–>B10). Transplantation 55, 1382–1389.

Wu, L., and Shortman, K. (2005). Heterogeneity of thymic dendritic cells. Semin. Immunol. 17, 304–312.