The influence of the Sustainable Seafood Movement in the US and UK capture fisheries supply chain and fisheries governance

- 1Department of Geography and Environment, Environmental Change Institute, Oxford, UK

- 2Applied Environmental Research Laboratories, Project Seahorse, Fisheries Centre, Vancouver, BC, Canada

- 3SCS Global Services, Emeryville, CA, USA

Over the last decade, a diverse coalition of actors has come together to develop and promote sustainability initiatives ranging from seafood eco-labels, seafood guides, traceability schemes, and sourcing policies in Western seafood supply chains. Based on a literature review, we trace the development of the Sustainable Seafood Movement, which has been working to reform sustainability practices in the seafood supply chain. Focusing on capture fisheries in the US and in the UK, we explore the roles of key actors and analyze the dynamics within and between actor groups through a cultural model derived from semi-structured interviews. We argue that the Sustainable Seafood Movement is different from previous social movements in that, in addition to actors advocating for government reform, it has motivated supply chain actors to participate in non-state market driven governance regimes. The movement and its actors have leveraged their legitimacy and authority garnered within the supply chain to increase their legitimacy and authority in public governance processes. As the movement continues to evolve, it will likely need to address several emerging issues to maintain its position of legitimacy and authority in both the supply chain and public governance processes.

Introduction

The Sustainable Seafood Movement is an outgrowth of the Environmental Movement, which began coalescing in the mid-to-late 1990s, in reaction to the declining status of global fish stocks and the lack of government responses (Konefal, 2013). In 1997, when the first US Status of Stocks report was issued, 86 fish stocks were overfished, 10 were approaching overfished condition, 183 were not overfished and 448 were unknown (NMFS, 1997). The Food and Agriculture Organization's 1997 State of the World Fishery Resources: Marine Fisheries report stated that 60% of the major global fish resources were plateauing at high exploitation levels or declining, and “given that few countries have established effective control of fishing capacity, these resources [were] in urgent need of management action to halt the increase in fishing capacity or to rehabilitate damaged resources (FAO, 1997).”

Non-government actors recognized that capture fisheries were in serious decline and that government regulators either did not have the tools or could not exercise the political will to address the situation (Sutton and Wimpee, 2008). Over the last two decades a diverse coalition of non-government actors have come together to address this governance gap. These actors include environmental non-governmental organizations (ENGOs), philanthropic foundations, certification schemes, verification experts, retailers, food service providers, restaurants, chefs, members of the fishing industry, academics, media and engaged consumers. This coalition of actors and their networks laid the basis for the Sustainable Seafood Movement (movement) which developed key objectives, including the development of non-state market driven governance tools to incentivize sustainable seafood supply chains and improve fisheries governance (Cashore, 2002; Sutton and Wimpee, 2008; Jacquet et al., 2009; Konefal, 2013).

One of the movement's first non-state market driven governance tools, the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) seafood eco-label, emerged from the partnership between Unilever, a large multi-national corporation, and World Wildlife Fund, an environmental non-governmental organization (Cummins, 2004). The MSC was developed outside of government-led processes, which heretofore had been the major mechanism for managing UK and US capture fisheries. Over time, the movement would develop a number of these tools, such as seafood guides, seafood sourcing policies, and voluntary labeling guidelines, as a means to create a non-state market driven governance regime.

While some of these non-state market driven governance tools, such as the MSC and to a lesser extent seafood buying guides, have been the subject of numerous studies, minimal attention has been paid to the diverse coalition of actors that came together to support the development of these tools (Gulbrandsen, 2009; Jacquet et al., 2009; Roheim et al., 2011; Froese and Proelss, 2012). Using the United Kingdom and the United States as case studies, this analysis explores the interplay between the various roles of the movement's actors, their objectives and the tools they have collectively created through the development of a cultural model derived from semi-structured interviews.

Social Movement Theory

Tarrow outlines the four characteristics of a social movement as “collective challenges, based on common purposes and social solidarities, in sustained interaction with elites, opponents and authorities (Tarrow, 2011).” Social movements form when social networks, organization, political opportunities and the emotions surrounding cultural frames are brought together (Tarrow, 2011). Cultural frames are the cognitive understandings or the mental models that people use to understand a situation. In the context of social movement theory, these cultural frames are often alternatives to what authorities or elites have constructed and are critical for constructing common meaning to incentivize common action (Tarrow, 2011). Divergent cultural frames can result in conflict between actors. As Kempton et al documented in the 1990s, the differences between actors' cultural models can explain why some actors support environmental action while others do not (Kempton et al., 1996). A social movement must attract participants to subscribe to its cultural frame in order to succeed. In securing adherents, its legitimacy is established (McLaughlin and Khawaja, 2000). Once legitimacy is established it is easier for a social movement to attract resources to sustain and propel it forward. Resource mobilization is critical to enable a movement to promote its objectives to a wider audience and contest the prevailing cultural frame (McLaughlin and Khawaja, 2000). Social movements are different from interest groups in that the former lack steady access to stable resources such that contention can become a key resource within a movement's control (Tarrow, 2011). Thus, a movement's contention of the dominant cultural frame offered by authorities or elites may become a focal point to maintain supporters and attract new recruits (Tarrow, 2011).

The Sustainable Seafood Movement

The Sustainable Seafood Movement is a social movement that began to arise in the mid to late 1990s from a coalition of ENGOs in response to the failure of governments to responsibly manage marine capture fisheries (Sutton and Wimpee, 2008). Sutton argues that despite ENGOs participation in fisheries regulatory processes, the influence of the fishing industry over government regulators and the regulatory process, meant that reform had to come through an alternative mechanism—the seafood supply chain (Sutton and Wimpee, 2008).

The effectiveness and aims of the movement have been critiqued in three articles (Jacquet and Pauly, 2007; Jacquet et al., 2009; Konefal, 2013). Jacquet et al.'s first manuscript describes a spectrum of ENGO activities that range from boycotts of retailers, to traceability and seafood fraud campaigns, to the proliferation of eco-labels and seafood buying guides. These activities are not framed in the context of a social movement. Jacquet et al. is critical of the effectiveness of these market-based efforts, such as seafood eco-labels, and advocates for ENGOs to engage governments in order to reduce fishing and to inform the public of overfishing in an effort to increase the accountability of policymakers (Jacquet and Pauly, 2007). In the second article, Jacquet et al. soften their stance toward market-based incentives but suggest that the emphasis on consumers was “premature” (Jacquet et al., 2009). They echo prior findings of the 2005 Bridgespan report, which recommended focusing limited resources on work with a finite number of corporate seafood buyers vs. attempting to engage diffuse networks of consumers. Jacquet et al. suggest several areas that the movement could also address (i.e., food miles, subsidies). This early literature focused mainly on the origins of the movement or critiques of market-based tools. Most of the recent academic and gray literature has focused on individual initiatives of the movement, such as eco-labels, seafood guides, boycotts, campaigns to improve traceability and ENGO-corporate partnerships (Roheim, 2009; Roheim et al., 2011; Bush et al., 2012; Froese and Proelss, 2012; Gutiérrez et al., 2012; Kirby et al., 2013). Within these publications, the exploration of actors has focused heavily on ENGOs or certification schemes (e.g., MSC), leaving out many other actors in the movement, their roles and relationships.

Konefal is the only author who has situated initiatives related to sustainable seafood in the context of social movements or broader cultural dynamics. He identifies the Sustainable Seafood Movement as part of the Environmental Movement and then critiques the movement's emphasis on market-based approaches as perpetuating further neoliberal “notions of individualism, marketization, and the devolution of regulatory authority (Konefal, 2013).” He contends that the large corporate foundations that financed many of the movement's initiatives perpetuated market-based approaches, devolving authority to markets, while promoting the commodification and consumption of seafood. He asserts that this approach diminishes the movement's transformative capacity contributing “to the [neoliberal] processes that undergird the exploitation of fisheries (Konefal, 2013).”

Non-state Market Driven Governance

Environmental or civil society movements over the last two decades have also substantially influenced other production sectors, such as forestry, coffee, cocoa, etc. Cashore identified this phenomenon as “non-state market driven governance” in his analysis of the forestry sector (Cashore, 2002). Non-state market driven governance regimes derive their authority not from the state, but from the marketplace. Cashore outlines four conditions of non-state market driven governance—(1) that the buyers down the supply chain use their demand to regulate the action of the producer in the marketplace, (2) that the state does not directly use its sovereign authority to require adherence to rules in the marketplace, (3) stakeholders/civil society gain authority through the evaluation process that producers must undergo in the marketplace, (4) enforcement of these marketplace processes comes through verification of compliance.

Critical to these non-state market driven governance regimes are the concepts of authority, legitimacy and credibility. Authority in this context relates not to sovereign authority, but the authority that civil society and other stakeholders are able to garner in the marketplace (Cashore, 2002). Cashore and other scholars have found that NGOs have garnered authority in the market-place for a variety of reasons, such as supply chain actors perceiving a market benefit from participating in these processes, moral suasion, and/or sustainability initiatives that have become an accepted norm in certain supply chains (Cashore, 2002; Foley and Hebert, 2013). Through interactions and transactions within the supply chain, actors, such as NGOs, demonstrate their legitimacy. An actor must be seen as legitimate in order to hold authority (Auld, 2009; Tarrow, 2011). Cashore builds on Suchman's work and asserts that there are three types of legitimacy present in non-state market driven governance regimes—pragmatic, moral, and cognitive legitimacy. Pragmatic legitimacy is based on self-interest of an organization, moral legitimacy is based on doing the right thing and cognitive legitimacy is based on main-streaming the standardization of a norm or process (Cashore, 2002).

Legitimacy is derived from the exchanges between actors, through which they demonstrate credibility over time. Credibility comes from the actions or actor demonstrating trustworthiness and responsibility (Boström, 2006; Tarrow, 2011). However, not all actors with legitimacy and authority in the supply chain are seen as credible (Tarrow, 2011; Miller and Bush, in press). In several cases, this has not prevented movement actors from exerting pressure on the supply chain to achieve their specific sustainability goals (Miller and Bush, in press).

In this article we will explore the movement's objectives, actors, their specific domains and relational roles, and how they have gained legitimacy, credibility and hence authority, in the supply chain as well as in public governance processes. We conclude by discussing emerging issues that the movement may need to address in order to maintain its current relevance.

Methods

The United States and the United Kingdom capture fishery supply chains serve as the case studies for this research given that the movement's organizers have targeted these markets first (Packard, 2007). These regions share a common language, have long-standing “special relationship” with a documented bi-directional exchange of innovation (Griffith et al., 2006; Tarrow, 2011), people and advocacy campaigns between the two countries (e.g., after UK ENGO supermarket rankings proved successful, US ENGOs adopted them). Other countries such as Canada and Australia have similar, equally developed movements, but are not explored here. Likewise, the aquaculture portion of the supply chain is not explored, as there are a number of sustainability issues that differ between aquaculture and wild capture fisheries.

After receiving approval from the University of Oxford's Research Ethics Committee, semi-structured interviews, ranging from 30 to 60 min, were conducted from 2012 to 2013 to explore the roles of the different US and UK actors (n = 24). Interviewees provided written consent that they were willing to participate in the study. Further, where possible, interviews were recorded and transcribed. When this was not possible, detailed notes were made. Participants received copies of their transcripts for review to ensure accuracy and often provided clarifying information in writing.

Structured questions focused on the roles of actors surrounding seafood eco-labeling, how they relate to each other and the ultimate purpose of seafood eco-labeling. The experts interviewed often worked on several facets of the seafood sustainability issue, hence the scope of interviews widened to discuss topics broader than seafood eco-labeling. Interviewees were selected based on their organization or their personal engagement with seafood sustainability initiatives, such as MSC or the Conservation Alliance for Seafood Solutions. These initial individuals also made recommendations to interview other actors. Interviews were supplemented with background interviews with key informants (n = 6) in cases where they did not feel comfortable with a recorded interview. All of the major actor groups, except for foundations and media, were directly interviewed either for a formal or background interview. Additional data on all the sector groups, and in particular the media and foundations, were also gathered through participant observation at major fora for seafood sustainability, such as the North American Seafood Expo (2013–2014) and analysis of peer-reviewed and gray literature.

The interview transcripts were then analysed in NVivo 10 using an inductive approach to coding to develop a cultural model as described in Naomi Quinn's “Finding Culture in Talk: A Collection of Methods” and Kempton et al.'s “Environmental Values in American Culture” (Kempton et al., 1996; Quinn, 2013). A cultural model or conceptual model is an informants' understandings of how a process or phenomenon operates, be it climate change, sustainable fisheries management, or some other aspect of nature or culture. Cultural models are shared among individuals but often not completely; there may be variation within and between groups. Elements of a cultural model can emerge from interviews and patterns of discourse evident in transcripts or other documents, such as common motifs that multiple members of the same group express when speaking about an issue. Through this analysis of interview transcripts, participant observation, which included attending talks and targeted conversations with key actors at major seafood sustainability events, and review of gray and peer-reviewed literature, cultural models emerge regarding the interests and roles of actors in the Sustainable Seafood Movement. This paper uses the cultural models expressed by diverse actors to examine the roles and the objectives that sectorial actors have relative to one another in the movement. In doing so, we are able to explore how the movement's actors have collectively facilitated their legitimacy, authority and credibility in the US and UK seafood supply chain and in public governance processes.

Results

Overview of the Movement and Cultural Frame

Our analysis found that there are 10 principal actor groups that compose the Sustainable Seafood Movement—ENGOs, foundations, certification schemes, verification experts, retailers/food service providers, chefs, the fishing industry, academics, consumers, and the media. (For the sake of brevity, we treat retailers and food service providers as one actor group and often refer to them collectively as retailers. While they play very similar roles in the movement, we recognize these are very different industries.) Within each actor group (e.g., retailers), different actors play different roles. It is important to understand the roles and interests of each actor within the movement as well as within their actor group because it reveals their common and divergent interests that sustain the movement. As Tarrow notes “interest” is the most common denominator of social movements (Tarrow, 2011). These interests inform the cultural frames that actors in a social movement hold and that can be influenced in order to create and sustain a common cultural frame necessary to bring about social solidarity in the movement.

Actors who share a cultural frame, share a common understanding of the basic problems facing fisheries. Based on our review of gray-literature, peer-reviewed articles and expert interviews, we have identified points of agreement and disagreement in the actors' cultural frame of fisheries sustainability. One of the principle points of disagreement that was evident in our interviews and in the literature has been the degree to which global fisheries are overexploited (Pauly, 1995; Worm et al., 2006, 2009; Murawski et al., 2007; Daan et al., 2011). ENGOs, foundations and the media tend to subscribe to the viewpoint that global fisheries are significantly overexploited and near collapse in several places. Academic opinions vary from calling for urgent action to address dire impacts, to oceans as models of relative resilience (Worm et al., 2006; Hilborn and Hilborn, 2012). Retailers, food service providers, chefs, certification schemes and verification experts express the view that there are sustainability issues in capture fisheries, but there are also recent success stories. The fishing industry tends to be the most cautious about the urgency of the situation.

While disagreement exists on the severity of exploitation in capture fisheries, there have been several influential processes that have helped to formulate a shared cultural frame in the Sustainable Seafood Movement. Prominent among these are regular stakeholder workshops and stakeholder council meetings that are part of the MSC program development, meetings of the Conservation Alliance for Seafood Solutions, the UK Sustainable Seafood Coalition and many others (Cummins, 2004; Conservation Alliance for Seafood Solutions, 2008). As a result, the movement's actors generally agree that fishing practices can be made more sustainable and in many places fish stocks need to be rebuilt. All actors that we interviewed or that we examined their organization's materials, also generally recognize that market-based approaches can improve the sustainability of fisheries by themselves or in concert with government regulation.

Organizers of the Sustainable Seafood Movement

Two roles have been critical to the initial organization of the movement—the organizers/bridge builders and the funders. ENGOs initially served the role as the organizer of the movement, given their history of organizing coalitions around environmental issues (Dunlap and Mertig, 1991). ENGOs are often long-standing professional organizations that have vast networks and experience in carving out a role in policy debates (McLaughlin and Khawaja, 2000). As the initial organizers of the movement, ENGOs were able to bring together disparate actors across the movement to “build bridges” in order to foster social solidarity through generating new cultural frames to contest established ones (Ward and Phillips, 2008). In the Sustainable Seafood Movement, actors like SeaWeb, an ENGO, have served as conveners of ENGOs and developed venues like the SeaWeb Seafood Summit, to foster dialogue between all the actors in the seafood supply chain. (Seaweb has since sold the SeaWeb Seafood Summit to Diversified Communications, however they continue to manage the content.) In this role, ENGOs have been the initial bridge builders of the movement, bringing together disparate and at times conflicting interests to chart a common vision for ensuring sustainable seafood in the supply chain and thus building a greater network of support for the Sustainable Seafood Movement. Over time other actors, such as retailers and fishing industry representatives, have increasingly shared this role.

Philanthropic foundations have provided the critical strategic direction and financial means for the Sustainable Seafood Movement to develop, grow and sustain its efforts to influence the supply chain and governments. While their work is not as visible as other actors in the movement, foundations have facilitated partnerships that did not previously exist and thus have been instrumental in the growth of the movement. Starting in the late 1990's, the David and Lucile Packard Foundation and Pew Charitable Trusts, which were dissatisfied with the pace and efficacy of government led fisheries management, identified market-based approaches as priorities for their marine conservation funding (Konefal, 2013). Packard's “Seafood Choice Initiative” used the Forest Stewardship Council as a model and identified five market-based approaches to support (1) Certification, (2) Consumer and gatekeeper education, (3) Single-species campaigns, (4) Business-environmental organization partnerships, and (5) Market campaigns (Konefal, 2013).

Konefal notes that prior to Packard's investment, there were virtually no ENGO market-based campaigns for seafood (Konefal, 2013). Konefal argues that some of the foundations involved in the Sustainable Seafood Movement have ties to large corporations that often have a vested interest in consistent supplies of sustainable seafood. While that may be the case in some instances, the diversity of foundations involved in the movement has expanded over time. Today, the strategic funding decisions of Packard, Pew, Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Prince's International Sustainability Unit and the Walton Family Foundation, amongst other foundations, continue to influence the direction of the Sustainable Seafood Movement.

Foundations have worked most directly with ENGOs and certification schemes (e.g., MSC) and through those relationships have indirectly affected verifiers, retailers, food service providers, chefs and the fishing industry. Academics focusing on fisheries sustainability and related supply chain issues, such as the University of British Columbia's Seas Around Us Project, have also received significant support from some of these foundations (Pew Charitable Trust). In addition, foundations have supported media or ENGO public education campaigns related to sustainable seafood production and consumption. Thus, foundations have supported the engagement and work of the majority of the actors in the movement.

The Movement's Objectives and Actors' Roles

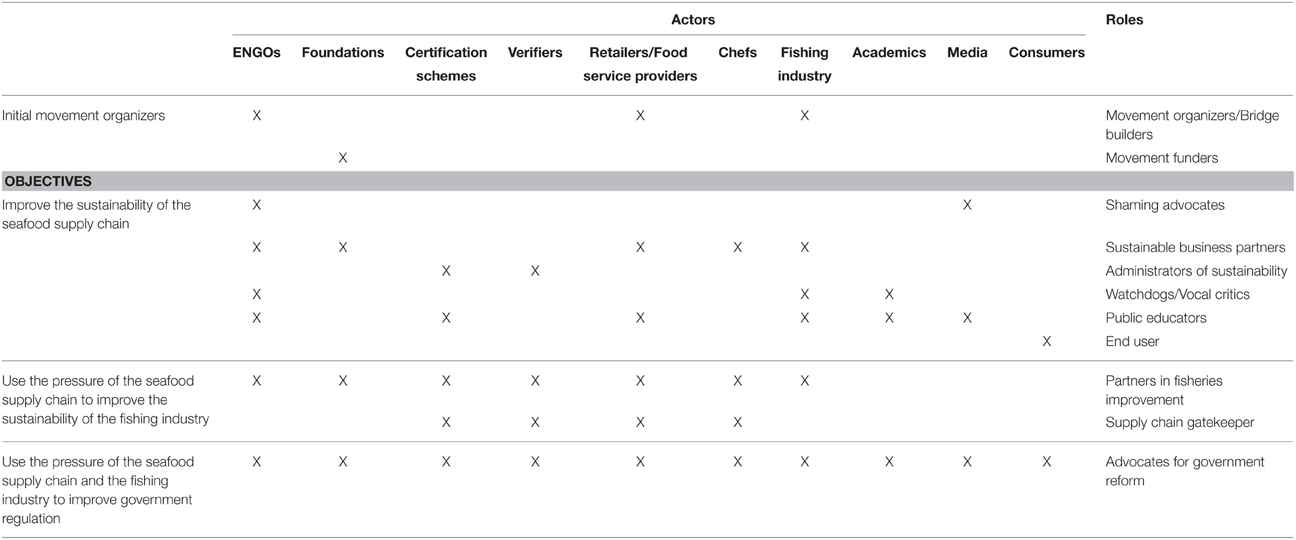

We analyzed the interview data and gray and peer-reviewed literature to determine the roles of the movement's 10 actor groups in achieving its three main objectives. Many actor groups play multiple roles within the movement. We discuss how these roles contribute to achieving each objective, in particular improving the sustainability of the seafood supply chain through the development of non-state market driven governance tools (see Table 1). To achieve this objective new relationships between actors have developed that did not previously exist, resulting in the movement obtaining legitimacy, authority and credibility in the supply chain. The movement has leveraged this to further its two other objectives—reform in the fishing industry and reform of government-led fisheries management.

Table 1. Objectives of the movement are captured on the left side; the actor groups are identified across the top and the different roles they play down the right side.

Objective—Improve the Sustainability of the Seafood Supply Chain

The majority of our analysis focuses on this objective as the movement had to dedicate substantial resources to it, since a shared cultural frame did not exist from which collective action could take place in the supply chain. To that end, the movement focused its energy on developing several non-state market driven governance tools in the supply chain to achieve the change it sought. Several different actor groups played different roles throughout this process. The following section details these roles and how these actors have come together to improve the sustainability of the seafood supply chain.

Shaming Advocates (ENGOs and the media)

Within the ENGO community, some ENGOs have developed a niche or role as Shaming Advocates. This extends to the Sustainable Seafood Movement, where Greenpeace is seen as and states they are willing to take “hard-scale” action. These actions include occupying supermarkets and encouraging consumers to boycott retailers or products. For example, Greenpeace occupied Loblaw supermarket's roof in Toronto in November 2008. In July 2009 in San Francisco, the organization launched a spoof website of Trader Joe's called “Traitor Joe's” to highlight their weak sustainable seafood sourcing policy (Ju, 2009; Black, 2010; Greenpeace, 2014). The media assists these shaming efforts by providing ENGO shaming advocates with a public platform for their boycotts.

Since 2008, Greenpeace US has published a “Carting Away the Oceans” (CATO) report, which ranks US supermarket retail chains on their procurement policies and evaluates relative engagement in fisheries policy reform (Trenor, 2009). The rankings are meant to spur action in retailers who are not sourcing sustainably produced seafood or who do not leverage their relative power as buyers to drive policy change. Critics argue supermarkets only participate to appease Greenpeace, yet several retailers actively advertise their improved CATO ranking relative to other retailers on their websites, legitimizing the report's findings; and also giving shaming advocates credibility (Target; Safeway).

Sustainable Business Partners (ENGOs, foundations, retailers, chefs and fishing industry)

The movement recognized early that an alternative to government regulation could be to leverage the self-interest of corporations to protect the stability of seafood supply through market-based incentives (Ward and Phillips, 2008). The 2006 Walmart and World Wildlife Fund partnership was one of the first large ENGO-Retailer Partnerships. Walmart committed to sourcing 100% of its seafood products from MSC certified fisheries within the next 3–5 years (Walmart, 2006). (The timeline later expanded and included participation in a fishery improvement project, MSC or equivalent.) Thereafter, more ENGO-corporate partnerships developed, often based on ENGOs providing free or cost-offset services to companies, including advice to reform seafood sourcing policies, consumer education and outreach, and more recently, corporate engagement in public policy issues related to fisheries management (Packard, 2007; Conservation Alliance for Seafood Solutions, 2008; Supermarket News, 2008).

In 2008, US ENGOs created the Conservation Alliance for Seafood Solutions (Alliance) to develop a consistent approach to major buyer partnerships (Conservation Alliance for Seafood Solutions, 2008). Through this Alliance, North American ENGOs developed common steps for working with retail partners to improve their sustainability policies, and more recently, to promote a common set of expectations for fishery improvement projects. The Alliance has facilitated a harmonized framing of the movement's main messages, which allowed ENGOs to have an unusually unified influence over the large buyers (chefs, food service providers and retailers) in the supply chain.

Several interviewees noted that ENGOs whose role focuses on Sustainable Business Partnerships have benefited from the existence of Shaming Advocates, like Greenpeace. Shaming Advocates can cause reputational risk to retailers or food service's brands, while Sustainable Business Partners can offer practical solutions to address this risk. This can enhance the credibility of ENGOs who serve this role as Sustainable Business Partners making chefs, retailers and food service providers more receptive to working with them.

These Sustainable Business Partners early on benefited from Greenpeace's actions to advocate for sustainable seafood sourcing policies. Over time, the scope of the CATO report has expanded to include public policy issues, allowing ENGOs working in the space of Sustainable Seafood Business Partners to engage their retail partners in public policy debates surrounding fisheries management. Thus, ENGOs engaged in the movement have leveraged each other's strengths to develop roles in the seafood supply chain in order to improve the sustainability of the supply chain as well as fisheries governance.

Administrators of sustainability (certification schemes and verification experts)

Certification schemes, particularly the MSC, are some of the most visible outgrowths of the Sustainable Seafood Movement. Some of the movement's organizers (ENGOs and foundations) recognized early on that market-based certification, like the Forest Stewardship Council, could benefit the seafood sector (Cummins, 2004; Ward and Phillips, 2008; Konefal, 2013). While certification schemes are typically discussed as the various standards (e.g., MSC), third party certification schemes usually comprise three main parties—standard holders, certification bodies and accreditation bodies. Standards holders are typically non-profit organizations dedicated to writing and updating requirements for their standard. Standards holders are neither certification bodies, nor accreditation bodies.

Certification bodies and accreditation bodies serve as the verifiers of the movement's non-state market driven governance tools. Certification bodies evaluate fisheries against performance indicators—the requirements of a standard—and may issue a certificate if the performance of a fishery is compliant with requirements. Accreditation bodies regulate the accreditation of certification bodies and may grant, suspend or withdraw accreditations (the right to issue certificates). Certification schemes differ meaningfully in their structure, both in terms of the governance of standards holders, the procedures to be used by certifiers, and even in whether accreditation bodies are associated with particular schemes (Environmental Law Institute, 2012; James Sullivan Consulting, 2012). Certification schemes have often used international norms, such as the Food and Agriculture Organizations' Guidelines for the Ecolabelling of Fish and Fishery Products from Marine Capture Fisheries, as a basis for their standards. As Cashore notes, by basing non-state norms on existing government rules and policies, non-state actors may be able to achieve cognitive legitimacy (Cashore, 2002).

Prominent standard holders for seafood certification in the US and UK market include MSC, Friends of the Sea, and Alaska Responsible Fisheries Management. Standard holders and certification body auditors play a unique role in the movement's effort to influence the supply chain since the assessment of fisheries by auditors from certification bodies is the main mechanism used to evaluate fisheries' sustainability. If a fishery fails to be certified, it can potentially lose access to a market, or may not receive other indirect benefits. Thus, these non-state market driven governance processes help to enforce the sustainability standards that the movement is advocating for in the supply chain.

It has taken time to mainstream standards in the supply chain, but with the adoption of sustainable seafood purchasing policies committing retailers to source certified seafood product, the legitimacy, authority and credibility of certification programs has increased (Miller and Bush, in press). Many corporate seafood buyers have embraced certification programs since it allows them to avoid developing the expertise to understand technical issues such as stock status, habitat impacts, and governance of different fisheries. Instead seafood buyers can rely on the expertise of standard holders and certification bodies to regularly assess the performance of fisheries against the standard. Certification schemes also provide a means for retailers to reduce risk (e.g., brand risk, supply shortages, etc.) in their supply chain and to demonstrate to consumers and ENGOs they have fulfilled their commitments to source sustainable seafood.

The development of certification schemes has been important in bringing together all of the movement's actors and identifying common interests. This has facilitated the movement's social solidarity, as well as exposed fractions. Certification schemes, particularly MSC, were initially strongly supported by many ENGOs as a means to ensure a best practice from producers. Over time, more movement actors, such as the fishing industry, retailers, foundations and academics, have become critical participants in certification schemes. This has resulted in certification schemes incorporating their interests into the process. As an increasing number of certifications have been granted, at times over the objections of ENGOS, the original ties between ENGOs and standards holders have in some cases loosened (Christian et al., 2013). In the next section, we discuss the ways the movement is trying to address the differing perspectives on certification schemes.

Watchdogs/Vocal Critics (ENGOs, fishing industry, and academics)

ENGOs have typically played the role of watchdogs on many different public policy issues (Dunlap and Mertig, 1991). This is also true for the Sustainable Seafood Movement. Watchdog ENGOs have highlighted numerous issues in the supply chain such as truth-in-labeling and disparities between eco-label schemes. In the United Kingdom, ClientEarth's investigation of environmental claims on seafood products demonstrated the rampant use of claims such as “sustainable seafood,” “sustainably caught,” “sustainably fished,” “responsibly caught,” could not be substantiated (ClientEarth, 2011). ClientEarth's investigation led to the development of voluntary guidelines for UK retailers, creating a new mechanism for the movement to influence the governance of the supply chain.

ENGOs, the fishing industry, and academics also serve as watchdogs/critics of the non-state market driven governance tools that the movement has developed, particularly certification schemes, though in very different ways. These actors often play a very active role in MSC policy reform via the MSC stakeholder council. In addition, ENGOs and academics have commented in favor of, and objected to, proposed MSC certifications during stakeholder comment periods (Christian et al., 2013; Gutiérrez and Agnew, 2013). Academics have studied the phenomena of certification schemes, their impacts on specific fisheries and offered critiques of certification schemes (Potts and Haward, 2006; Bear and Eden, 2008; Oosterveer, 2008; Gulbrandsen, 2009; Bush et al., 2012). As more third party certification schemes have entered the marketplace, ENGOs such as the World Wildlife Fund and the Environmental Law Institute, have conducted benchmarking exercises or legal reviews to evaluate the rigor of various eco-label schemes (Environmental Law Institute, 2012; James Sullivan Consulting, 2012). The fishing industry has also been critical of certification schemes given they often bear the cost of certification without a commensurate level of benefits experienced by parties such as retailers (MAFAC, 2013; Stoll and Johnson, 2015). The growing number of certification schemes and the costs associated with acquiring multiple certifications that different retailers may require, has exacerbated the fishing industry's concern.

The movement's actors also work together to identify solutions to emerging needs that could undermine the solidarity of the movement. For instance, many of the movement's actors collaborated to establish the Global Seafood Sustainability Initiative (Initiative). This Initiative aims to reduce costs in the supply chain by benchmarking certification schemes so that retailers have a mechanism to determine equivalency of process and performance considerations within certification schemes. In theory, this may allow retailers to allow multiple certification schemes. Thus, potentially reducing the need for the fishing industry to obtain several different certifications to comply with various retailers' buying policies. This Initiative is an attempt to develop consensus around minimum expectations for seafood sustainability standards. The viability of this consensus in the supply chain will depend on whether it can accommodate the concerns of all the movement's actors and the market realities of any outcomes. Through the consensus-building process, the roles of the network of actors are further refined and new organizational networks are built. As Tarrow argues, social movements do more than just contend, “they build organizations, elaborate ideologies, and socialize and mobilize constituencies (Tarrow, 2011).” This regular collaboration amongst movement actors has helped to build shared cultural frames and objectives.

Public educators (ENGOs, certification schemes, retailers, chef, fishing industry, academics and media)

Many of the movement's actors have engaged in the role of educating the public, though in slightly different ways. Retailers, food service providers, restaurants and chefs, of all the participants in the movement are in a unique position to educate consumers about the importance of sustainable seafood and ocean conservation because consumers often interact with these actors on a daily or weekly basis. Retailers, food service providers and restaurants are capitalizing on this role by explaining their sourcing policies on-line and at the point of sale, along with providing material explaining the importance of sustainable fisheries to consumers (Fields, 2012; Whole Foods, 2012; Sainsbury's, 2013). Several restaurants have built their brand around sustainability and undertaking consumer outreach on marine conservation. With the rise of the celebrity chefs in society, chefs are increasingly using their restaurants, their television shows and their cookbooks to educate the public about the need for sustainable seafood. ENGOs are working with retailers, restaurants and chefs to improve the reach of their sustainability messages as well as to learn from these actors how ENGOs' roles within the movement may help to meet their needs. For instance, the New England Aquarium works with chefs like Barton Seaver who educate the culinary community and engage the public.

ENGOs have always engaged the public either directly, through social media and/or traditional media, particularly those affiliated with conservation centers, such as aquariums. Seafood ranking criteria and consumer seafood cards, such as Monterey Bay Aquarium's Seafood Watch or the UK's GoodFish Guide, were one of the Sustainable Seafood Movement's first initiatives (Ward and Phillips, 2008). These assessment systems were designed to motivate consumers to demand sustainable seafood in the supply chain. Some ENGOs initially had a cultural model that assumed mobilizing consumers to ask for sustainable seafood would in turn exert pressure on seafood retailers to pressure fishermen to fish more sustainably (Ward and Phillips, 2008). To that end, several ENGOs around the world developed seafood cards. However, critics maligned ENGOs for not having a unified set of buying recommendations, causing confusion among consumers and at times impacting the economies of certain fisheries when they were rated red (i.e., avoid this purchase) (Roheim, 2009; Schmitt, 2011). While ENGOs in the Sustainable Seafood Movement made substantial efforts to coordinate their engagement with corporate retailers, several interviewees noted that these efforts did not yield a fully unified rating system. There has however, been convergence between rating systems and more recently, some rating systems have started to give MSC certified fisheries an automatic yellow (i.e., good alternative) (MSC, 2013a).

Around 2005, major philanthropic foundations refined their funding strategies, which in turn shifted ENGOs' focus: moving away from systems used to convince large numbers of consumers to shift their demand to sustainable seafood toward the more achievable option of influencing the relatively limited number of corporate seafood buyers (Packard, 2007). This in turn meant that for certain movement actors, corporate seafood buyers became a target audience, instead of the general public. While, ENGOs continue to provide educational material to consumers through seafood guides and more recently, seafood guide apps, these efforts are largely focused on raising awareness and do not presume that these tools will cause changes in consumer behavior. Some interviewed felt that consumer awareness remains important to ensure that retailers honor their pledges to implement sustainable seafood sourcing policies.

In addition to seafood rating cards, the active engagement of the media in the movement has been critical to reaching a large public audience quickly. All the of the movement's actors, particularly ENGOs, certification schemes, food retailers and academics, generate stories that the media covers. Influential media outputs, such as major films and documentaries can be sponsored or advised by movement actors, such as foundations or ENGOs, respectively. For instance, Charles Clover's book The End of the Line served as the basis for an important documentary to raise awareness about the state of global fisheries (Clover, 2006). Greenpeace UK and Waitrose served as important advisors to this project. While the media may not be the central actor in the movement, they are the actor with the greatest ability to reach a significant public audience quickly.

End users

While consumers are not key actors in the movement, they are the ultimate recipients of the supply chains' products. Thus, their potential to boycott or support retailers remains a critical point of leverage over the supply chain (Gutiérrez and Thornton, 2014). The Sustainable Seafood Movement initially led several targeted campaigns to raise consumer awareness, but with the strategic decision to work directly with corporate buyers to reform production practices more rapidly, consumer targeted programs have not received the same effort as ENGO-corporate relationships (Packard, 2007).

Market research has indicated that “eco-warriors,” those that both have and act on their sustainability ideals, are a relatively small segment of the market (Galloway, 2010). Research indicates that consumers care about buying sustainable seafood, but there remains a behavioral gap between understanding the need for sustainable seafood and buying accordingly: this disconnect remains a challenge for the movement (Oosterveer and Spaargaren, 2011). As more MSC product has become available in the market place, awareness has decreased in the United States from 23 to 21% and increased in the United Kingdom from 18 to 31% (MSC, 2012). It is not clear if these changes relate to variations in the availability of MSC product, consumer engagement in market-based initiatives, or label awareness. Several studies indicate that eco-labels or ratings systems by themselves may not motivate consumers to buy sustainable product (Bear and Eden, 2008; Hallstein and Villas-Boas, 2013; Gutiérrez and Thornton, 2014; Uchida et al., 2014). Hallstein et al. showed that when seafood rated green, yellow and red was available, along with mercury information, sales decreased for yellow with no mercury concern (Hallstein and Villas-Boas, 2013). Unless messaging is very clear, consumers may become confused and/or avoid purchasing altogether.

Objective—Use the Pressure of the Seafood Supply Chain to Improve the Sustainability of the Fishing Industry

Partners in fisheries improvement (ENGOs, foundations, certification schemes, verifiers, retailers, chefs and fishing industry)

During the 2000s, as retailers and their ENGO partners made public commitments to sustainable seafood purchasing policies, several interviewees recounted the gap in processes to improve and reform fisheries quickly in order to maintain a steady, profitable and longstanding supply of seafood. As discussed in the introduction, at that time government fisheries managers had not demonstrated the ability to improve stock status at the pace and scale necessary to meet retailer's needs, even in countries with large management budgets and sufficient agency capacity (O'Leary et al., 2011). Actors in the movement recognized fisheries would not meet the standards of third party certification programs like MSC unless their management and performance improved. ENGOs, with support from foundations, once again organized partnerships with retailers and innovative members of the fishing industry to close this gap. This work included addressing issues identified by verification experts in confidential MSC pre-assessments, so that fisheries could enter MSC full assessment. Later, and with many retailers unable to meet their procurement policy commitments, ENGOs and retailers/food service providers developed fishery improvement projects to work directly with fishermen to improve fisheries (Conservation Alliance for Seafood Solutions, 2014). As several interviewees noted, these improvements often are incentivized through preferential market access via seafood rankings or benchmarking against elements of the MSC standard and/or the risk of losing market access without these improvements. Retailers/food service providers may directly work with seafood producers to help them through the certification process and then develop marketing materials around a successful certification (Whole Foods, 2012).

While ENGOs have been critical in organizing partnerships, change on the water is fundamentally controlled by the fishing industry and their participation in the movement is critical. In some instances, even before the emergence of the MSC, seafood companies like Heinz took steps to communicate through labeling to their consumers that their product was dolphin-safe (Baird and Quastel, 2011). As the MSC standard became established, its first big fisheries included some of the leading actors in the Alaskan pollock and salmon fisheries, who participated in part because they were incentivized by the potential of a price premium. Over time, seafood processors and fishermen, working with ENGOs and retail partners, have identified innovations, such as new or modified fishing gear to reduce impacts and new observer technology, in order to improve the sustainability of key fisheries. For instance, the International Seafood Sustainability Foundation (ISSF), founded in 2009, is a collaborative between academics, ENGOs, and tuna processors, seeking to improve the status of tuna and Regional Fisheries Management Organization's management of tuna stocks, in areas where tuna has been poorly managed (ISSF). By improving tuna management practices, tuna fisheries should be able to obtain MSC certification for retail markets. The willingness and leadership of members of the fishing industry to innovate from within and to work collaboratively with other movement actors to achieve aligned goals such as certification, has improved the sustainability of fisheries.

Gatekeeper of the supply chain (certification schemes, verifiers, retailers and chefs)

As mentioned in the earlier section, commitments by large retailers, such as Walmart, Sainsbury's, Marks and Spencer, and many others have helped to influence the seafood buying practices of the retail sector (Walmart, 2006; Sainsbury's, 2013). Several of those interviewed from ENGOs and retailers noted that as sustainable seafood procurement policies have become the industry norm, retailers have changed suppliers and in some cases obtained MSC chain of custody, to carry certified claims on seafood in their store thus exercising their role as gatekeepers to the supply chain. ENGOs can pressure or shame retailers to use their buying leverage to promote or prevent certain product from entering the marketplace. For instance, as a result of Greenpeace's advocacy, several retailers have stopped carrying shark, orange roughy and Bluefin tuna (Trenor and Mitchell, 2013). Further, the outcomes of audits by verification experts can determine whether product meets a retailers' sourcing policy. As a result of retailers implementing sustainable seafood sourcing policies, there is an increased availability of sustainable product. Using the MSC as a proxy, almost 10% of the total wild capture is MSC certified and more than 25,000 products carry the MSC logo (MSC, 2015).

Food service providers and restaurants have not traditionally labeled their products the way retailers do, so consumers in cafeterias/restaurants generally have to either trust or ignore whether their seafood was sustainably sourced. Recent efforts have increased responsible seafood procurement and labeling initiatives by food service providers and restaurants. For example, McDonald's 14,000 plus US restaurants are now MSC chain of custody certified and use the MSC logo on their pollock Filet-o-Fish packaging (Seafoodsource, 2013). Through initiatives such the UK's Sustainable Fish Cities, which is working to encourage major institutions to only source sustainable seafood, colleges, universities, hospitals, prisons, and schools are developing sustainable seafood sourcing policies so these supply chain actors can also act as gatekeepers for responsibly produced fish. Chefs can also act as gatekeepers between suppliers and consumers. Seaweb's “Give Swordfish a Break” campaign successfully persuaded chefs to refrain from sourcing North Atlantic Swordfish in order to allow the stock to rebuild (Ward and Phillips, 2008). Supply chain gatekeepers incentivize other actors' participation in non-state market driven governance schemes, like MSC or fishery improvement projects, at the same time exerting consequences—loss of market access—to those who do not.

Objective—Use the Pressure of the Seafood Supply Chain and the Fishing Industry to Improve Government Regulation

Advocates for government reform (all movement actors)

Retailer and ENGO collaborations have progressed beyond procurement policies and assuring supplies of sustainable seafood to now include collaborations on public policy issues. For example in the UK, Marks and Spencer and other retailers made public statements on the need to ban discards during the recent EU Common Fisheries Policy reform (Harvey, 2014). US retailers formally commented on the Bristol Bay mine's impact on salmon populations either individually or through their industry group, the Food Marketing Institute (USA; FMI). Chefs have also engaged in public debates related to sustainable seafood, giving TED talks and lobbying legislators within their jurisdictions for sustainable fisheries. A visible example has been Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall's “Fish Fight” series in the UK, which has highlighted fishing gear impacts on benthic habitat and discards. The “Fish Fight” website urges consumers to ask supermarkets about procurement policies, to demonstrate purchasing support for sustainable seafood, and to urge local politicians to take positions on fisheries reforms (FishFight). As a result of the Sustainable Seafood Movements' organized network of partnerships, the constituency groups engaged in public policy debate related to fisheries management has expanded to include retailers, chefs, food service providers, academics, consumers, certification schemes, verification experts, and the media in addition to the traditional constituents—the fishing industry and ENGOs.

Of all the actors, the fishing industry is in a unique position since participating in non-state market driven governance regimes does not alleviate the fishing industry's regulatory obligations, such as quota allocation, observer requirements, etc. Thus, in practice, both public and private governance processes now regulate the fishing industry. Some in the fishing community have embraced this and see the two processes as mutually supportive. For instance, the MSC certification of the US West Coast shrimp trawl fishery allowed the fishery to re-evaluate their management goals and put in place clearer processes to achieve them (MSC, 2009). Similarly, the recent MSC pre-assessment of the inshore fisheries in England highlighted areas where the fishing industry and government need to work to improve stock status and management practices. Industry and government representatives found the pre-assessment analysis a helpful tool to evaluate their efforts to date (MSC, 2013b). Further, the inshore fleet is composed of smaller vessels that have had less political power, but by participating in the MSC pre-assessment they were able to garner greater attention from policymakers. Members of the fishing industry that participate in the movement, have often been able to translate proactive action for sustainability into legitimacy and authority in the supply chain and in turn increasing either personal or organizational influence in traditional governance processes (Ward and Phillips, 2008).

Discussion

Our analysis depicts the actors, their roles and the objectives of the Sustainable Seafood Movement. Several of the movement's non-state market driven governance tools, such as certification schemes, fishery improvement project, voluntary guidelines, seafood sourcing policies or seafood guides, are discussed in the literature separately. By framing these non-state market driven governance tools in the context of the Sustainable Seafood Movement, we see the breadth of the movement's governance regime, its actors, the roles they play and their common objectives. Through our analysis of interview data, peer-reviewed and gray literature, we found that the movement's actors have come to have a shared cultural frame as to why the movement is needed and what it can do to improve the sustainability of fisheries.

However, the movement's actors often have divergent long-term goals. When the interviewees were asked about the ultimate purpose of these market-based incentives and the work of the sustainable seafood movement, six views were commonly given, though not by all actors. ENGOs offered a vision where one day there would only be sustainable seafood in the marketplace forcing out seafood produced using unsustainable practices. Academics and ENGOs explained that ultimately the movement would like to see improved transparency in government processes and the seafood supply chain in order to ensure sustainable fisheries. ENGOs and retailers used the phrase “change on the water” to describe the movement's purpose as propelling more sustainable fisheries. ENGOs, academics and chefs talked about sustainable fisheries leading to healthy ecosystems that included a broad concept of sustainable fisheries, marine protected areas, and thriving biodiversity all ultimately leading to a healthier society.

All of the interviewees talked about the need for shared responsibility in some facet, though from very different vantage points. ENGOs saw shared responsibility as consumers, retailers, chefs and food service providers understanding the issue of sustainable fisheries and actively buying sustainable product, the fishing industry taking responsibility for improving the sustainability of fisheries, government regulators managing to ensure sustainable fisheries and ENGOs ensuring accountability and transparency in the process. However, some of the fishing industry representatives had a different perspective, and felt part of the ENGO community sees this vision occurring through the fishing industry bearing the cost of sustainability and were resistant to this approach. And finally, some ENGOs and certification programs, particularly those that work with the fishing industry, described the ultimate goal as “working themselves out of a job” as the fishing industry would take responsibility for the sustainability of fisheries. This divergence of goals amongst the movement's actors may present challenges to movement over the long-term.

Challenges and Future Directions

Contested Spillover of Authority

As we have discussed throughout the paper, one of the movement's most successful non-state market driven governance tools have been seafood certification schemes. These schemes have become a legitimate means to validate a product's sustainability in the supply chain and more recently have spilled over into US and UK public procurement processes. As a result, certain members of the fishing industry have become frustrated with the cost of certification and the loss of brand identity, leading to tensions in the movement. In the summer of 2013, the movement's authority was contested when controversy erupted over the potential loss of market access for some Alaskan salmon producers. Walmart and Sodexho, a vendor to the US National Park Service, independently sent letters to Alaskan salmon producers that were no longer MSC certified reiterating that their respective buying policies specified that they purchase MSC certified product. Several Alaskan salmon producers had left the MSC program and hired a private company, Global Trust, to establish a third party certification program with a consumer-facing label, called the FAO-based Responsible Fisheries Management Standard (Foley and Hebert, 2013). In 2011, Global Trust certified Alaska's salmon fisheries as “responsibly managed” (Foley and Hebert, 2013). (A portion of the fishery maintains MSC certification and in November 2013 a new certificate was issued to the new client.) Since, the FAO-based Responsible Fisheries Management Standard was not recognized in the aforementioned buying policies, some Alaskan salmon producers were at risk of losing market access.

Given the importance of the Alaskan salmon industry to the state economy (ex-vessel value of $575 million in 2012) these salmon producers appealed to government officials, outside of the movement for remedy (McDowell Group, 2013). Alaskan Senators called a Congressional hearing to explore why these sustainability standards had been incorporated into the government procurement processes of the US General Service Administration and the US National Park Service. Alaskan Senators highlighted that the Alaskan state constitution mandates sustainable yields and that Alaskan salmon stocks, in contrast to many of the world's fisheries, have not been found to be either overfished or subject to overfishing (Convention, 1956; NOAA Fisheries, 2013). They questioned why the US National Park Service or their supplier (Sodexho) required MSC certification of their suppliers.

Given the political pressure, the US General Service Administration announced new vendor guidelines that rely on US government information (Fishwatch.gov) rather than sourcing standards that movement's actors typically used (Petersen, 2013). At the same hearing, Walmart announced they would evaluate whether the Responsible Fisheries Management Standard was equivalent to MSC and thus met their sourcing criteria; in late 2013 it was deemed equivalent. (In 2015, several of the Alaskan salmon producers decided to rejoin the MSC program because of European supply chain sourcing policies).

This example highlights the ongoing challenge the movement faces to its authority and legitimacy in the supply chain, as more fishing industry groups feel pressure to subscribe to requirements of this non-state market drive governance regime. While mechanisms such as public reviews of the MSC criteria or seafood ratings programs (e.g., Seafood Watch), exist for actors inside and outside the movement to express their concerns, some actors will continue to feel marginalized and contest the authority of the movement's sustainability tools such as certification and ranking systems by appealing to government authorities.

Shared Responsibility

One way to address the issues of contested authority and legitimacy is for the movement's actors to equitably distribute the responsibility of sustainability across the supply chain. Fishing industry participants that tend to operate in higher volume, were amongst the first to participate in the movement. As non-state market driven governance tools have become mainstreamed, fishermen that operate in small fisheries with smaller profit margins are struggling to adopt and participate in these processes. This is particularly true of third party certification where costs are often borne by the fishing producers vs. the ultimate recipients of certified product: retailers and consumers. Seafood ratings can also close markets for fishermen operating in fisheries determined to be “red” (i.e., avoid this purchase), such as fisheries affected by Whole Foods' adoption of the Monterey Bay Aquarium rating system (Eilperin, 2012). In some cases the seafood rating could be based on lack of government regulation and because these are smaller operators and/or a less consolidated industry, they have limited influence on both the regulatory authorities as well as the corporate seafood buyers. If the goal of the movement, as articulated by several interviewees, is to ensure that markets carry only sustainable product it will become an economic necessity for actors in the supply chain, and particularly at the upper end of the supply chain, to share in the cost of sustainability.

This is particularly true when it comes to consumers. The Sustainable Seafood Movement initially focused on consumers, but quickly found it to be more effective to target corporate seafood buyers (Packard, 2007). While a segment of the consumer market is willing to align purchasing power with social/environmental aims there is not sufficient evidence at present to support that the majority of consumers understand the need and respond by purchasing those products (Devinney and Auger, 2010). While seafood guides and eco-labels aid interested consumers, they also focus on an individual commodity rather than connecting consumers to the larger sustainability issues of ocean health and sustainable fisheries.

Interviewees expressed the importance of motivating consumers to make sustainability an overriding factor in their seafood purchases and in working with retailers to set sustainable sourcing policies as a default, so that consumers do not have to engage in complex sustainability decision-making. By making “sustainable” a default buying specification, consumers can assume/trust that the work is done for them: at the same time they may not understand or see the importance of having sustainable sources of seafood (Eden et al., 2008). Hence it remains essential for consumers to understand the issues associated with sustainable fisheries production, which may help consumers to accept possible cost increases. If the responsibility to ensure sustainable fisheries is not equitably shared across the supply chain, the market may not be able to bear the costs, limiting the transformative capacity of the movement.

Emerging Markets

Our analysis focused on US and UK markets, which tend to have more industrialized fleets that have consolidated and reduced fishing effort over the last decade, as governments have introduced regulations to address overfishing and ecosystem impacts (Teh and Sumaila, 2011). Fishing effort in developed countries has moved to emerging markets as fish stocks have declined, yet these areas often have less information and capability to sustainably manage these stocks (Worm and Branch, 2012). This allows companies to operate less expensively and with limited or no regulation. Retailers with procurement policies that operate internationally can be instrumental in urging emerging markets to adopt stronger governance either in the supply chain or through government processes. For example, several key actors in the US market established the aforementioned International Seafood Sustainability Foundation because they depend on tuna imports and recognized the weak governance in international tuna fisheries was undermining their sustainability goals and presenting reputational risks. In some markets, the movement's tools—such as certification—allow for greater transparency and inclusion of a more diverse set of stakeholders than government-led processes. In addition, the assessments for the certification schemes are at times more robust and credible than those developed by governments. The movement's non-state market driven governance regime could potentially complement or serve in the place of public governance mechanisms in emerging markets. This creates both opportunities and challenges for the movement, depending upon the histories and cultures of the market question.

Growing Scope of Sustainability

The traditional emphasis of the Sustainable Seafood Movement has been on environmental sustainability. Recently, interest in social sustainability has increased. The Environmental Justice Foundation's work in Africa and Asia highlighting human rights abuses in foreign fishing fleets, and advocating for legal and safe working conditions for fishers may prove a reform challenge for both domestic and international fleets (EJF, 2014). In 2015, FairTrade USA released V1.0 of a capture fisheries standard that links social and labor considerations in fisheries with environmental sustainability. Food waste and food miles have also entered into the movement's discussion and some actors are trying to incorporate this into the movement's core work. However, the expertise for these newer issues often lies outside of the movement. The movement will have to determine whether to tackle these issues or identify them within the seafood supply chain for the human rights and climate communities to address.

Concluding Remarks

The Sustainable Seafood Movement is a transnational social movement whose non-state market driven governance tools, such as seafood cards and third party certification programs, are typically analyzed independent of the overall social movement, the role of various actors or its core objectives. We argue that analyses of discrete non-state market driven governance tools such as eco-certification are incomplete unless they are in the context of the objectives and goals of the social movement within a broader political-ecological context. Over the last decade, the movement's initial organizers, ENGOs, foundations, retailers and the fishing industry, have successfully built a network of actors that share a common, overarching, cultural model—a desire to improve the sustainability of capture fisheries via the supply chain, through the establishment of a non-state market driven governance regime. The movement's network of actors has successfully developed several of these tools in the supply chain and used this to influence reforms in the fishing industry and in government-led fisheries management. The ability of the Sustainable Seafood Movement to maintain and grow its legitimacy, authority and credibility in the supply chain and public governance processes may depend on its ability to deal with emerging challenges, such as contested authority, shared responsibility, emerging markets and the multi-faceted tenets of sustainability.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Thomas F. Thornton for his invaluable comments on early drafts. We would also like to thank all of the members of the Sustainable Seafood Movement in the United States and the United Kingdom that agreed to be interviewed for this article, many of whom have provided innovation and leadership to reform their own sectors within the movement. And finally, the first author would like to thank the NOAA Fisheries Advanced Studies program for supporting her research. The second author would like to thank SCS Global Services for allowing participation in academic publications.

References

Baird, I. G., and Quastel, N. (2011). Dolphin-safe tuna from California to Thailand: localisms in environmental certification of global commodity networks. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 101, 337–355. doi: 10.1080/00045608.2010.544965

Bear, C., and Eden, S. (2008). Making space for fish: the regional, network and fluid spaces of fisheries certification. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 9, 487–504. doi: 10.1080/14649360802224358

Black, J. (2010). Trader Joe's Adopts Sustainable Seafood Standards. 1–3. Available online at: https://www.washingtonpost.com

Boström, M. (2006). Establishing credibility: practising standard-setting ideals in a Swedish seafood-labelling case. J. Environ. Policy Plann. 8, 135–158. doi: 10.1080/15239080600772126

Bush, S. R., Toonen, H., Oosterveer, P., and Mol, A. P. J. (2012). The “devils triangle” of MSC certification Balancing credibility, accessibility and continuous improvement. Mar. Policy 37, 288–293. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2012.05.011

Cashore, B. (2002). Legitimacy and the privatization of environmental governance: how non-state market-driven (NSMD) governance systems gain rule-making authority. Governance 15, 1–27. doi: 10.1111/1468-0491.00199

Christian, C., Ainley, D., Bailey, M., Dayton, P., Hocevar, J., LeVine, M., et al. (2013). A review of formal objections to Marine Stewardship Council fisheries certifications. Biol. Conserv. 161, 10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2013.01.002

Clover, C. (2006). The End of the Line. London; New York, NY; Berkeley, CA: Ebury Press; The New Press; University of California Press.

Conservation Alliance for Seafood Solutions (2008). A Common Vision for Environmentally Sustainable Seafood. Conservation Alliance for Seafood Solutions. Available online at: http://www.solutionsforseafood.org/projects/common-vision/

Conservation Alliance for Seafood Solutions (2014). Guidelines for Supporting Fishery Improvement Projects. Conservation Alliance for Seafood Solutions. Available online at: http://www.solutionsforseafood.org/projects/fishery-improvement/

Convention, A. C. (1956). The Constitution of the State of Alaska. Available online at: http://ltgov.alaska.gov/treadwell/services/alaska-constitution/entire-constitution-text.html

Cummins, A. (2004). The Marine Stewardship Council: a multi-stakeholder approach to sustainable fishing. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manage. 11, 85–94. doi: 10.1002/csr.56

Daan, N., Gislason, H., Pope, J. G., and Rice, J. C. (2011). Apocalypse in world fisheries? The reports of their death are greatly exaggerated. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 68, 1375–1378. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsr069

Devinney, T. M., and Auger, P. (2010). The Myth of the Ethical Consumer. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dunlap, R. E., and Mertig, A. G. (1991). The evolution of the U.S. environmental movement from 1970 to 1990: an overview. Soc. Nat. Resour. 4, 209–218. doi: 10.1080/08941929109380755

Eden, S., Bear, C., and Walker, G. (2008). Mucky carrots and other proxies: problematising the knowledge-fix for sustainable and ethical consumption. Geoforum 39, 1044–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2007.11.001

Eilperin, J. (2012). Some Question Whether Sustainable Seafood Delivers on its Promise. washingtonpost.com, 1–4. Available online at: http://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/some-question-%E2%80%A6le-seafood-delivers-on-its-promise/2012/04/22/gIQAauyZaT_print.html

EJF (2014). Slavery at Sea. EJF. Available online at: http://ejfoundation.org/sites/default/files/public/EJF_Slavery-at-Sea_report_2014_web-ok.pdf

Environmental Law Institute (2012). Seafood Certification Based on FAO Guidelines and Code of Conduct: A Credible Approach? Washington, DC: Environmental Law Institute.

FAO (1997). Review of the State of the World Fishery Resources. Rome: FAO. Available online at: http://www.fao.org/docrep/003/w4248e/w4248ef1.htm#A1

Fields, B. (2012). Netting Results with Sustainable Seafood. walmartgreenroom.com, 1–3. Available online at: http://www.walmartgreenroom.com/2012/10/netting-results-with-sustainable-seafood/ [Accessed February 25, 2014].

FishFight (ed.). FishFight. Available onine at: http://www.fishfight.net/ [Accessed February 28 2014].

FMI. Food Marketing Institute Public Comments on EPA's Ecological Risk Assessment for Bristol Bay Mine. Food Marketing Institute. Available online at: http://www.ourbristolbay.com/pdf/FMI-BristolBay-letter-20120301.pdf

Foley, P., and Hebert, K. (2013). Alternative regimes of transnational environmental certification: governance, marketization, and place in Alaska's salmon fisheries. Environ. Plann. A 45, 2734–2751. doi: 10.1068/a45202

Froese, R., and Proelss, A. (2012). Evaluation and legal assessment of certified seafood. Mar. Policy 36, 1284–1289. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2012.03.017

Greenpeace (2014). Loblaws Targeted by Greenpeace. Greenpeace.org. Available online at: http://www.greenpeace.org/canada/en/recent/loblaws-targeted-by-greenpeace/ [Accessed February 25, 2014].

Griffith, R., Harrison, R., and Van Reenen, J. (2006). How special is the special relationship? Am. Econ. Rev. 96, 1859–1875. doi: 10.1257/aer.96.5.1859

Gulbrandsen, L. H. (2009). The emergence and effectiveness of the Marine Stewardship Council. Mar. Policy 33, 654–660. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2009.01.002

Gutiérrez, A., and Thornton, T. F. (2014). Can consumers understand sustainability through seafood eco-labels? Sustainability 6, 8195–8217. doi: 10.3390/su6118195

Gutiérrez, N. L., and Agnew, D. J. (2013). MSC objection process improves fishery certification assessments: a comment to Christian et al. (2013). Biol. Conserv. 165, 1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2013.06.002

Gutiérrez, N. L., Valencia, S. R., Branch, T. A., Agnew, D. J., Baum, J. K., Bianchi, P. L., et al. (2012). Eco-label conveys reliable information on fish stock health to seafood consumers. PLoS ONE 7:e43765. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043765

Hallstein, E., and Villas-Boas, S. B. (2013). Can household consumers save the wild fish? Lessons from a sustainable seafood advisory. J. Environ. Econ. Manage. 66, 52–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jeem.2013.01.003

Harvey, F. (2014). “EU Ministers to ban fish discards,” in The Guardian, 4. Available online at: http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2011/mar/01/eu-ban-fish-discards/

Hilborn, R., and Hilborn, U. (2012). Overfishing: What Everyone Needs to Know. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

ISSF (ed.). International Seafood Sustainability Foundation. Available online at: http://iss-foundation.org/ [Accessed November 2013]

Jacquet, J., Hocevar, J., Lai, S., Majluf, P., Pelletier, N., Pitcher, T., et al. (2009). Conserving wild fish in a sea of market-based efforts. Oryx 44, 45. doi: 10.1017/S0030605309990470

Jacquet, J., and Pauly, D. (2007). The rise of seafood awareness campaigns in an era of collapsing fisheries. Mar. Policy 31, 308–313. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2006.09.003

James Sullivan Consulting (2012). Comparison of Wild-Capture Fisheries Certification Schemes. Gland: World Wildlife Fund.

Kempton, W., Boster, J. S., and Hartley, J. A. (1996). Environmental Values in American Culture. Cambridge, MA: The MITPress.

Kirby, D. S., Visser, C., and Hanich, Q. (2013). Assessment of eco-labelling schemes for Pacific tuna fisheries. Mar. Policy 43, 1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2013.05.004

Konefal, J. (2013). Environmental movements, market-based approaches, and neoliberalization: a case study of the sustainable seafood movement. Organ. Environ. 26, 336–352. doi: 10.1177/1086026612467982

MAFAC (2013). Marine Fisheries Advisory Committee. MAFAC. Available online at: http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/ocs/mafac/meetings/2013_05/docs/050913-noaa-final.pdf

McDowell Group (2013). Economic Value of the Alaska Seafood Industry. Juneau, AK: Alaska Seafood Marketing Institute.

McLaughlin, P., and Khawaja, M. (2000). The organizational dynamics of the U.S. environmental movement: legitimation, resource mobilization, and politicial opportunity. Rural Sociol. 65, 422–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1549-0831.2000.tb00037.x

Miller, A. M. M., and Bush, S. R. (in press). Authority without credibility? Competition conflict between eco-labels in tuna fisheries. J. Clean. Prod. 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.02.047. Available online at: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959652614001930

MSC (2013a). Monterey Bay Aquarium rates MSCCertified Seafood As Recommended Buy. msc.org, 1–1. Available online at: https://www.msc.org/newsroom/news/monterey-bay-aquarium-rates-msc-certified-seafood-as-recommended-buy [Accessed May 7, 2015a].

MSC (2013b). Partner Release: Report Completes Sustainability Map of England's 450+ Inshore Fisheries. MSC. Available online at: http://www.msc.org/newsroom/news/parner-release-report-completes-sustainability-map-of-england2019s-450-inshore-fisheries?fromsearch=1&isnewssearch=1&b_start:int=20 [Accessed March 1, 2014b].