- 1State Key Laboratory of Soil and Sustainable Agriculture, Institute of Soil Science, Chinese, Academy of Sciences, Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, P.R. China

- 2Graduate School of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, P.R. China

Nitrogenous fertilizers are generally thought to have an important role in regulating methane oxidation. In this study, the effect of ammonium on methane oxidation activity was investigated in a paddy soil using urea at concentrations of 0, 50, 100, 200, and 400 μg N per gram dry weight soil (N/g.d.w.s) and ammonium sulfate at concentrations of 0, 50, and 200 μg N/g.d.w.s. The results of this study demonstrate that urea concentrations of 200 μg N/g.d.w.s. and above significantly inhibit methane oxidation activity, whereas no statistically significant difference was observed in methane oxidation activity among soil microcosms with urea concentrations of less than 200 μg N/g.d.w.s after incubation for 27 days. Similar results were obtained in a sense that methane oxidation activity was inhibited only when the ammonium sulfate concentration was 200 μg N/g.d.w.s in soil microcosms in this study. Phylogenetic analysis of pmoA genes showed that nitrogen fertilization resulted in apparent changes in the community composition of methane-oxidizing bacteria (MOB). Type I MOB displayed an increased abundance in soil microcosms amended with nitrogenous fertilizers, whereas type II MOB dominated the native soil. Furthermore, although no statistically significant relationship was observed between pmoA gene and amoA gene abundances, methane oxidation activity was significantly negatively correlated with nitrification activity in the presence of urea or ammonium sulfate. Our results indicate that the methane oxidation activity in paddy soils might be inhibited when the concentration of ammonium fertilizers is high and that the interactions between ammonia and methane oxidizers need to be further investigated.

Introduction

Methane (CH4), a potent greenhouse gas (GHG), is involved in a number of chemical and physical processes in the earth's atmosphere, including global warming (Crutzen, 1995). Despite a short residence time in the atmosphere (10 years), the ability of CH4 to absorb infrared radiation is 20–30 times greater than that of CO2 (Rodhe, 1990). CH4 is more abundant in the Earth's atmosphere now than at any time in at least the past 650,000 years (IPCC, 2007). It has been estimated that 70% of the CH4 annually released into the atmosphere is due to human activities including agriculture, waste disposal, and biomass burning (Houghton et al., 2001). During most of the last 150 years, atmospheric CH4 has increased monotonically. However, even though the CH4 concentration in the atmosphere became erratic and did not increase overall from 1999 until 2007, it has begun to increase again (Rigby et al., 2008).

Paddy fields are an important source of atmospheric CH4, contributing approximately 40 Tg year−1 (Lelieveld et al., 1998; Wang et al., 2004). CH4, which is produced in the soil, enters the roots of the rice plants and is transported through the gas vascular system of the plants to the atmosphere, and oxygen is transported from the atmosphere into the roots. Thus, rice roots are partially oxic, which allows methane-oxidizing bacteria (MOB) to be active in the rhizosphere (Conrad, 2004). MOB associated with the rhizosphere of rice plants oxidize CH4 aerobically and use it as a source of carbon and energy. Thus, MOB play an important role in the global CH4 budget by reducing CH4 emissions from rice ecosystems to the atmosphere (Groot et al., 2003).

When considering the world's continued population growth and economic prosperity, rice production must increase by 40% by 2030 to satisfy the growing demand without adversely affecting the resource base (Khush, 2005). The increasing demand for rice has led to the intensified application of nitrogenous fertilizers, which may affect CH4 oxidation because MOB are generally thought to be inhibited by ammonium-based fertilizers, as has been demonstrated for soils (Steudler et al., 1989; King and Schnell, 1994; Gulledge et al., 1997) and sediments (Bosse et al., 1993; Van der Nat et al., 1997). This outcome is at least partially due to the strong evolutionary links between the genetics of enzymes responsible for CH4 and ammonia oxidation, which allow MOB and ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB) and/or ammonia-oxidizing archaea (AOA) to switch substrates (Dunfield and Knowles, 1995). This mechanism is believed to be responsible for the inhibition of CH4 uptake in soils exposed to high concentrations of available N (Hanson and Hanson, 1996).

In contrast, numerous studies have demonstrated that the activity and growth of MOB in the root zone of rice plants are stimulated upon fertilization (Bodelier et al., 2000a,b; Krüger et al., 2002; Krüger and Frenzel, 2003; Mohanty et al., 2006). This stimulating effect may be the result of a relief in N-source limitation or a direct stimulation of CH4 oxidation by NH+4-N by an as yet unknown mechanism (Bodelier et al., 2000a), and a schematic overview of the general mechanisms by which N-fertilization can influence CH4 production and oxidation in wetlands and uplands has been proposed by Bodelier (2011). It is noteworthy to mention that some studies have also demonstrated no effects of ammonium-based N-fertilization on MOB (Dunfield et al., 1995; Delgado and Mosier, 1996; Dan et al., 2001). Even though the effects of nitrogenous fertilizers on CH4 oxidation have been the most investigated regulating factor of aerobic CH4 oxidation (reviewed in Bodelier and Laanbroek, 2004; Aronson and Helliker, 2010), it is obvious that the interactions between the nitrogen and methane cycle are complex and far from completely understood (Bodelier, 2011). Therefore, microcosm incubations were performed to investigate the effects of urea and ammonium sulfate on methane oxidation in a paddy field to better understand the interactions between the methanotrophic community and ammonia-oxidizing prokaryotes.

Materials and Methods

Soil

The soil used in this study was collected from a long-term field fertilization experiment at the Changshu Ecological Experimental Station of the Institute of Soil Science, Chinese Academy of Sciences. The paddy soil was developed from lake sediment and is classified as a Typic Haplanthrept based on U.S. soil taxonomy. A full description of this long-term fertilization experiment and its management regimes has been previously described (Wu et al., 2011). A rice–wheat rotation system was maintained in the field, and soil sampling was performed from triplicate plots that received chemical fertilizers (NPK) during the rice-growing season. Bulk soil (top 0–5 cm) was collected and transported on ice to the laboratory immediately after sampling.

Microcosm Incubation

Five grams of fresh soil was placed into a 120 ml crimp top serum vial, and treatments of 0, 50, 100, 200, and 400 μg urea-N/g d.w.s or 0, 50, and 200 μg (NH4)2SO4-N/g d.w.s were established in duplicate. For the soil microcosms amended with (NH4)2SO4, 388 μg Na2CO3-C /g d.w.s was also added as the carbon source for ammonia oxidizers. All soil microcosms contained slurries with a final volume of 50 ml through the addition of sterile distilled water. The bottles were then sealed with rubber stoppers, and CH4 was injected into the headspaces to generate the targeted methane concentration of ~5,000 parts per million. The incubation of soil microcosms was performed at 28°C in the dark with shaking at 200 rpm for 27 days. After consumption of >95% of the CH4, the vials were flushed with air to remove any CO2 and to ensure that the slurries remained aerobic. The treatments were then renewed after 0, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, and 24 days of incubation, providing the targeted concentrations of CH4 and nitrogenous fertilizers described above. CH4 concentrations were measured on a daily basis or every other day, and inorganic nitrogen (NO−3, NO−2, and NH+4) concentrations were determined at days 0, 15, and 27.

Gas samples were collected to determine the CH4 concentration in the headspace of the microcosms. Before gas samplings, the bottles were gently shaken by hand for 1 min to release the CH4 dissolved in the submerged water layer into the headspace. One milliliter of the gas sample in the headspace was analyzed using gas chromatography with a flame ionization detector, as described previously (Liu et al., 2011). Soil slurries were collected after 0, 15, and 27 days of incubation. Before sampling, the bottles were vigorously shaken by hand; 10 ml of the slurries were transferred to centrifuge tubes and then centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 5 min to collect the soil pellets. The pellets were then stored at −20°C for molecular analysis. The supernatants were collected and stored at −20°C for inorganic nitrogen analysis. Inorganic nitrogen species (NH+4, NO−3, and NO−2) were extracted with 2 M KCl and analyzed using a continuous flow analyzer (SA1000, Skalar, Netherlands).

Soil DNA Extraction and Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction

DNA was extracted from approximately 0.5 g of soil pellet following the method of Griffiths et al. (2000) with slight modifications following a bead-beating step, which was performed in triplicate. The quality and quantity of the DNA was assessed using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE). Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) with three replicates for each sample was performed to determine the copy numbers of the amoA and pmoA genes using the primer sets Arch-amoAF/Arch-amoAR for AOA (Francis et al., 2005), amoA-1F/amoA-2R-GG for AOB (Rotthauwe et al., 1997) and A189f/mb661r for MOB (Costello and Lidstrom, 1999) with a CFX96 Optical Real-Time Detection System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). The qPCR standard was generated using plasmid DNA from representative clones containing the bacterial or archaeal amoA gene or bacterial pmoA gene. A dilution series of a standard template across six orders of magnitude (3.12 × 102 to 3.12 × 108 for AOB, 1.56 × 102 to 1.56 × 108 for AOA and 1.82 × 102 to 1.82 × 108 for MOB) per assay was used to optimize the qPCR conditions. The blank was always run with water as the template instead of the soil DNA extract. The 20 μl reaction mixture contained 10.0 μl of SYBR Premix Ex Taq (TaKaRa Biotech, Dalian, China), 0.25 μM of each primer, and 2 μl of DNA template. The PCR conditions used for the archaeal and bacterial amoA genes were the same as previously described (Jia and Conrad, 2009). For the pmoA gene amplification, the PCR conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95°C for 30 s; 40 cycles consisting of denaturation at 95°C for 10 s, primer annealing at 55°C for 30 s and elongation at 72°C for 30 s. PCR amplification efficiencies of 101.9% with a R2 value of 0.998, 99.2% with a R2 value of 0.990 and 101.4% with a R2 value of 0.993 were obtained for the archaeal amoA gene, the bacterial amoA gene and the pmoA gene, respectively. The specific amplifications of amoA and pmoA were also determined using a melting curve analysis, which always resulted in a single peak.

Polymerase Chain Reaction–Denaturing Gradient Gel Electrophoresis (DGGE)

For the DGGE analysis, PCR amplification of the archaeal and bacterial amoA gene was performed using the same primers as described above; however, the forward primer for the bacterial amoA was attached to a GC-clamp. The PCR reaction was performed in a 25 μl volume containing 2.5 μl 10 × PCR buffer, 0.25 μM of each primer, 200 μM (each) deoxyribonucleoside triphosphate, 1.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase, and 1 μl of soil DNA. The PCR was performed in a Thermal Cycler Dice (Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan), as previously described for the AOA (Francis et al., 2005) and AOB (Nicolaisen and Ramsing, 2002). The PCR products were run in a 1.5% agarose gel to determine their specificity and were spectrophotometrically measured to determine their concentrations.

Approximately 150 ng of PCR amplicons from each sample was subjected to DGGE analysis. For AOA, the PCR products were run in 6% acrylamide gels with a denaturing gradient of 20–50% (100% denaturant corresponds to 7 M urea and 40% deionized formamide). For AOB, an 8% gel with a 45–75% denaturing gradient was used. The gels were run in 1 × TAE at 75 V for 17 h and stained with SYBR Green I dye. The stained gels were imaged (Gel Doc system, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA), digitized, and processed (Gelcompar II, Applied Maths, Inc., Austin, TX).

Sequencing and Phylogenetic Analysis

The distinct DGGE bands for the amoA genes of AOB (10 bands) and AOA (5 bands) among all the treatments were excised and re-amplified using the previously described PCR conditions. These PCR products were cloned using the pEasy-T1 cloning kit (TransGen Biotech Co., Beijing). The clones that contained the correct insert were selected and sequenced using an ABI 3730 XL DNA analyzer (Beijing Genomics Institute, Beijing, China). For MOB, the PCR products from the five treatments [original soil sample (day 0), 4th week Urea-0 (U-0), 4th week Urea-400 (U-400), 4th week AS-0 (AS-0), and 4th week AS-200 (AS-200)] were directly used for the cloning to construct a clone library. The cloning was performed following the same procedure as described above. At least 6–12 clones were randomly selected for each treatment. The sequences for the DGGE bands and the clones as well as their closest relatives obtained by BLAST analyses (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) were aligned using CLUSTAL X 1.83 (Thompson et al., 1997). Phylogenetic trees were constructed using the neighbor-joining method based on the Jukes–Cantor correction MEGA (Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis) version 4 (Tamura et al., 2007).

Statistics

Spearman's correlation analyses were performed to assess the relationships among methane oxidation activity, nitrification activity and the abundance of the MOB (SPSS 11.5 package, SPSS, Chicago, IL). A One-Way ANOVA with Duncan's post hoc tests was performed to evaluate the differences within the datasets, with a P value of 0.05 selected for significance.

Nucleotide Sequence Accession Numbers

The sequences obtained in this study have been deposited in GenBank with the accession numbers JQ990075–JQ990084, affiliated with the AOB; JQ990070–JQ990074, affiliated with the AOA and JQ990085–JQ990125, affiliated with the MOB.

Results

CH4 Oxidation Activity

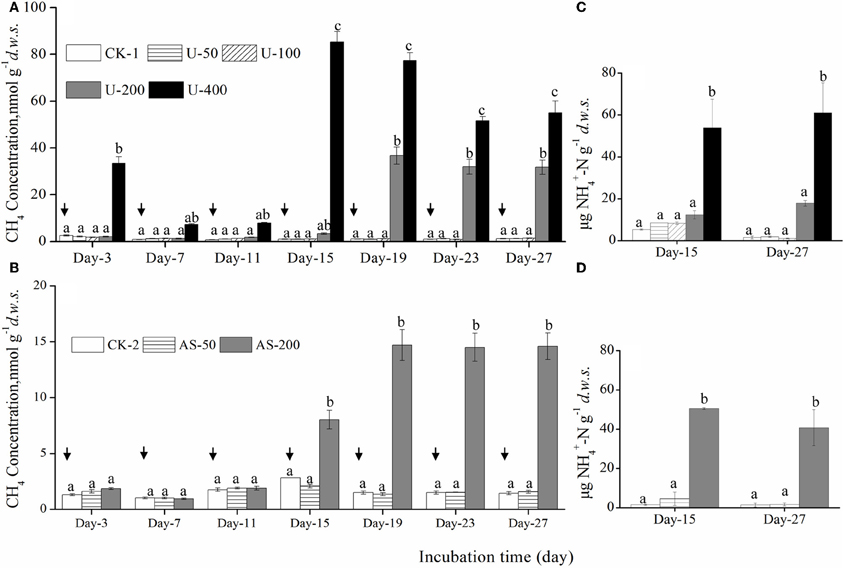

The initial CH4 concentration in the headspace was approximately 2.5 μmol g−1d.w.s., and methane oxidation was influenced by nitrogenous fertilizers during the microcosm incubations (Figure 1). After 27 days of incubation, there were no statistically significant differences in the CH4 concentrations among the soil microcosms amended with 0, 50, and 100 μg urea N/g.d.w.s. (1.14, 1.20, and 1.32 nmol/g.d.w.s., respectively), but significantly higher CH4 concentrations were observed in the headspaces of the soil microcosms containing 200 and 400 μg urea N/g.d.w.s (31.7 and 55.0 nmol/g.d.w.s., respectively; Figure 1A). The methane concentrations were 1.57 and 1.45 nmol/g.d.w.s. in the microcosms treated with ammonium sulfate at concentrations of 0 and 50 μg N/g.d.w.s., respectively (Figure 1B). A significantly higher CH4 concentration of 14.6 nmol/g.d.w.s. was observed in the microcosms when treated with 200 μg (NH4)2SO4-N/g.d.w.s. It is interesting to note that the ammonium concentrations were remarkably higher in the soil microcosms where CH4 oxidation was apparently inhibited by U-400 and AS-200 (Figures 1C,D). For example, 61 μg NH+4-N g−1d.w.s. was observed in the soil microcosms treated with 400 μg urea N/g.d.w.s., which is compared to 1.5 μg NH+4-N g−1d.w.s in the soil microcosms that received no nitrogenous fertilizers.

Figure 1. Changes in the CH4 concentrations in the headspaces of soil microcosms amended with urea (A) or ammonium sulfate (B) over an incubation course of 27 days as well as changes in the concentrations of NH+4-N in the soil microcosms (C,D). The designations CK-1, U-50, U-100, U-200 and U-400 represent the soil microcosms that received no fertilization, 50, 100, 200, and 400 μg urea-N/g d.w.s., respectively. The designations CK-2, AS-50, and AS-200 represent the soil microcosms treated with no fertilization, 50 and 200 μg ammonium sulfate-N/g d.w.s., respectively. The arrows indicate the repeated addition of CH4, i.e., an initial concentration of ~ 5,000 ppm CH4 in the headspace was re-established after an incubation period of approximately three days. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the duplicate microcosms, and the same letter above the columns refers to no statistically significant difference among the treatments (P > 0.05).

Nitrification Activity

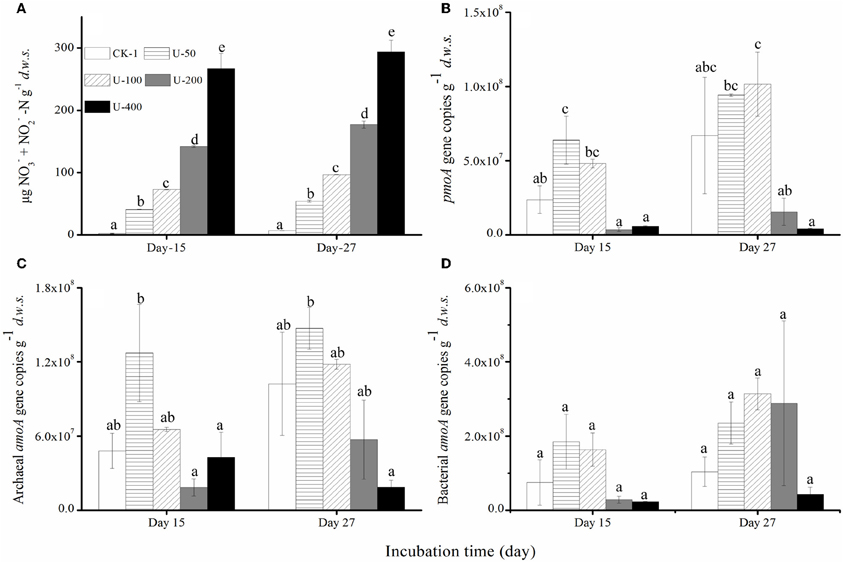

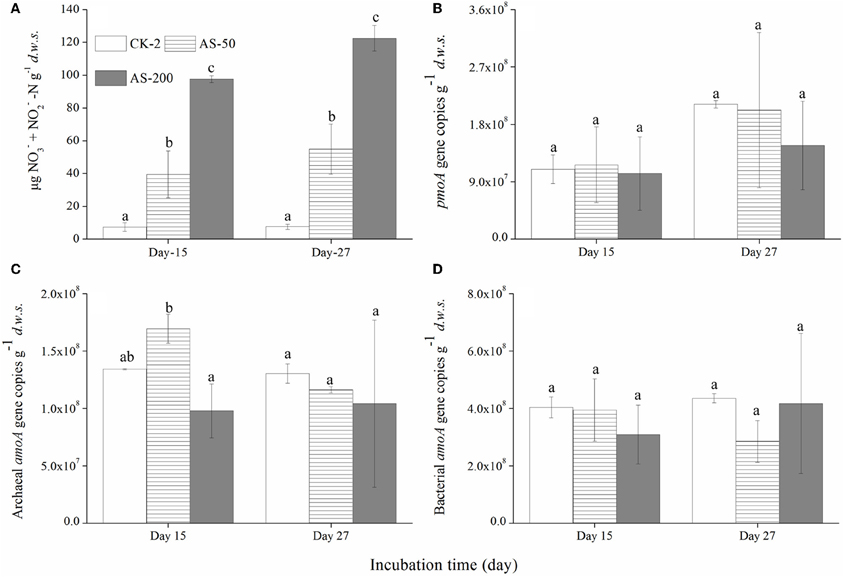

Regardless of the urea and (NH4)2SO4 treatments, there was a strong nitrification activity in the presence of CH4. The production of nitrate and nitrite in the soil microcosms was positively related to the amounts of urea or (NH4)2SO4 added (Figures 2A and 3A) while the native soil contained only 1.54 μg (nitrate + nitrite) N g−1d.w.s. All the microcosms treated with urea and (NH4)2SO4 displayed significant productions of soil nitrite and nitrate, demonstrating a strong nitrification activity over the course of the 27-day incubation. After 27 days of incubation, the soil nitrate and nitrite concentrations reached 294 μg N/g.d.w.s. and 123 μg N/g.d.w.s. in the microcosms amended with 400 μg urea-N/g.d.w.s. and 200 μg (NH4)2SO4-N/g.d.w.s., respectively (Figures 2A and 3A). As for the ammonium concentrations, 7.45 μg N/g.d.w.s. was observed in the native soil, and the consumed ammonium was recovered in an almost stoichiometric amount to the nitrate and nitrite produced in the soil microcosm after 15 or 27 days of incubation. Similar findings were observed in the soil microcosms amended with ammonium sulfate.

Figure 2. Changes in the concentrations of NO−3 and NO−3-N (A) the abundances of the pmoA genes of the methane-oxidizing bacteria (B) and the amoA genes of the Archaea (C) and Bacteria(D) in the soil microcosms amended with urea. The designations are the same as in Figure 1. The error bars represent the standard deviation of the duplicate microcosms, and the same letter above the columns refers to no statistically significant difference among the treatments (P > 0.05).

Figure 3. Changes in the concentration of NO−3 and NO−3-N (A) the abundances of the pmoA genes of the methane-oxidizing bacteria (B) and the amoA genes of the Archaea(C) and Bacteria(D) in the soil microcosms amended with ammonium sulfate. The designations are the same as in Figure 1. The error bars represent the standard deviation of the duplicate microcosms, and the same letter above the columns refers to no statistically significant difference among the treatments (P > 0.05).

Abundance of MOB, AOB, and AOA Communities

The abundances of MOB, AOB, and AOA were determined using a qPCR targeting the pmoA and amoA genes (Figures 2B–D and 3B–D). The pmoA gene copy number varied significantly in the soil microcosms with different nitrogenous substrates. For the native soil, the copy number of the pmoA genes was 1.37 × 107 g−1d.w.s. After 27 days of incubation, the pmoA gene copy numbers were 9.42 × 107 and 1.02 × 108 in the soil microcosms treated with 50 and 100 μg urea N/g.d.w.s, respectively. In the microcosms containing 200 and 400 μg urea N/g.d.w.s., copy numbers of 1.56 × 107 and 4.27 × 106 were observed as well as 6.70 × 107pmoA genes within the control microcosms receiving no urea. Similarly, the pmoA gene copy numbers decreased slightly in the soil microcosms containing 50 and 200 μg (NH4)2SO4-N/g.d.w.s compared to the control microcosms receiving no (NH4)2SO4-N. After 27 days of incubation, the copy numbers of the pmoA genes were 2.1 × 108, 2.0 × 108 and 1.5 × 108 in the soil microcosms treated with 0, 50, and 200 μg (NH4)2SO4-N/g.d.w.s., respectively.

The abundance of AOB and AOA amoA genes also varied within the soil microcosms amended with the different nitrogenous fertilizers. For the native soil, the bacterial and archaeal gene copy numbers were 1.34 × 108 and 1.12 × 108, respectively. After 27 days of incubation, the bacterial amoA gene copy number increased with the application of 50, 100, and 200 μg urea N/g.d.w.s, as compared to the control treatment, while a decrease in the copy number was observed in microcosms treated with 400 μg urea N/g.d.w.s. Similar results were observed for the copy numbers of the archaeal amoA genes, and a lower abundance of 1.87 × 107 was found in the soil microcosms that received the highest addition of N (400 μg urea N/g.d.w.s.). As for the (NH4)2SO4 treatment, the abundances of MOB, AOA and AOB appeared to remain constant over the course of the incubation (Figures 3B–D)

Relating Methane and Ammonia Oxidations with Functional Gene Abundances

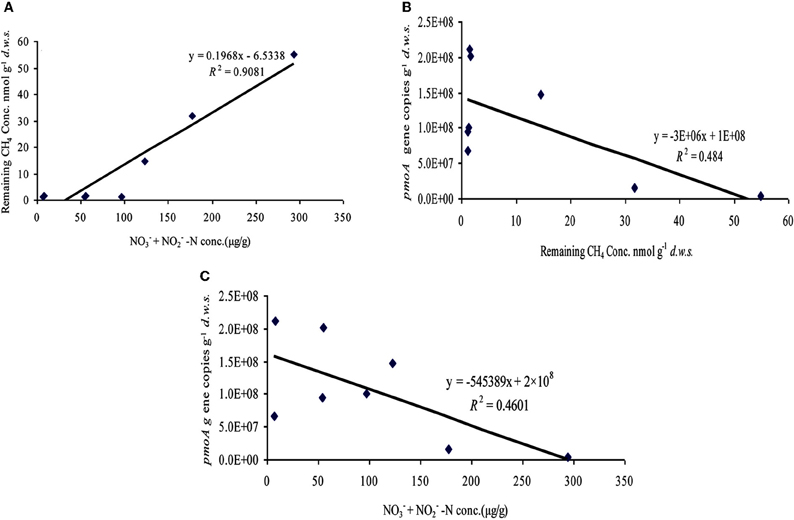

Regression analysis among the concentration of CH4 remained in the headspace, the amount of NO−2 and NO−3-N and the copy number of pmoA genes in the soil microcosms amended with urea and ammonium sulfate after 27 days of incubation were performed (Figure A1). Despite not being statistically significant (R2 = 0.484), CH4 oxidation was positively correlated with pmoA gene copy number. For instance, soil microcosms containing 200 and 400 μg urea N/g.d.w.s displayed a decreased pmoA gene copy number with lower CH4 oxidation rates after 27 days of incubation, as compared to the control treatment. Similar results were obtained for ammonium sulfate-amended treatment Interestingly, CH4 oxidation activity was significantly negatively correlated with the concentrations of NO−2 plus NO−3-N in the presence of urea and/or ammonium sulfate (ρ = −0.838), and the copy number of pmoA genes was negatively correlated with the concentration of NO−2 plus NO−3-N (ρ = −0.485). Moreover, the ratio of AOA to AOB was significantly positively correlated with CH4 oxidation activity (ρ = 0.57) but negatively correlated with the concentration of NO−2 plus NO−3-N (ρ = −0.48).

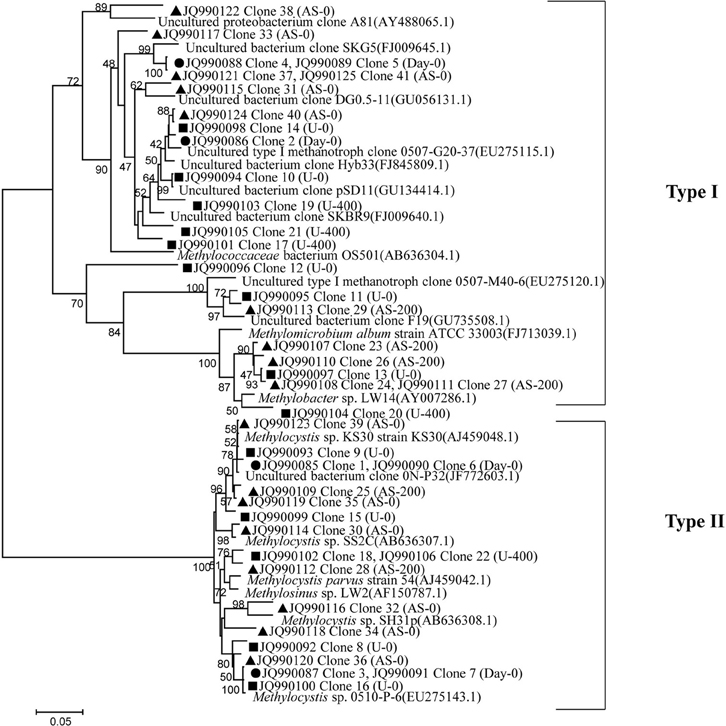

Community Compositions of MOB, AOB, and AOA

Clone library of pmoA genes was constructed, and phylogenetic analyses indicated contrasting changes of type I and II MOBs among the treatments (Figure 4). In total, 23 out of 41 sequences (up to 56%) were classified as type I MOB, and the remaining 18 sequences were related to type II MOB. For the native soil sample, the ratio of type I to type II MOB was 0.75. After a 27-day incubation period, the ratios of type I to type II MOB were 1.22, 2.03, 1.00, and 2.45 for the U-0, U-400, AS-0, and AS-200 treatments, respectively. The type I MOB were affiliated with the Methylobacter, Methylomicrobium, Methylococcus and uncultured methanotrophic clones, whereas the type II clones were phylogenetically related to the Methylocystis and Methylosinus genera and uncultured clones.

Figure 4. Neighbor-joining tree showing the relationships of the pmoA genes retrieved from the clone library in this study to those in GenBank. The scale bar indicates 5 changes per 100 nucleotide positions. Bootstrap values (>40%) are indicated at the branch points. • represents the native soil (day 0), and ▲ and ■ represent the ammonium sulfate-and urea-amended soil microcosms, respectively.

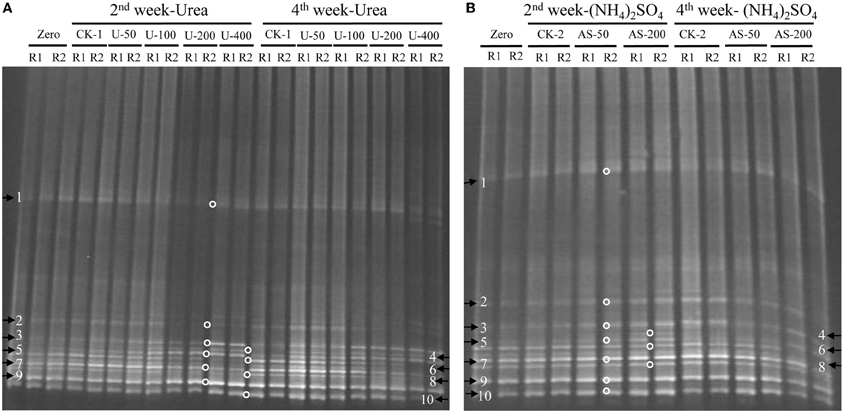

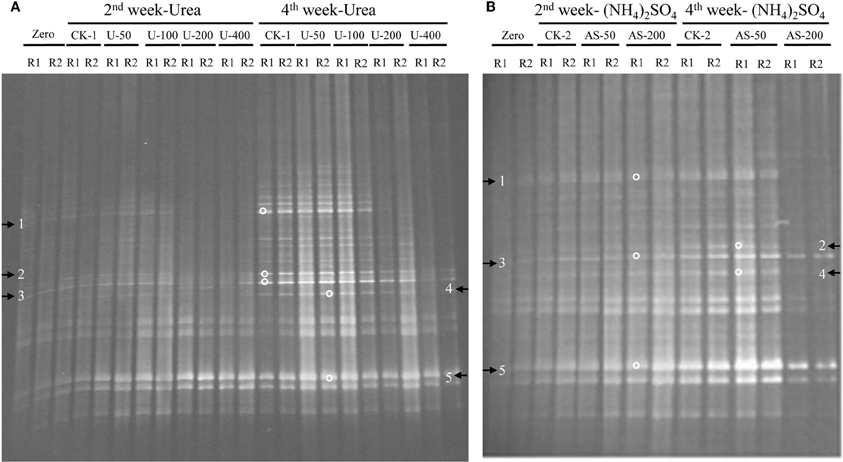

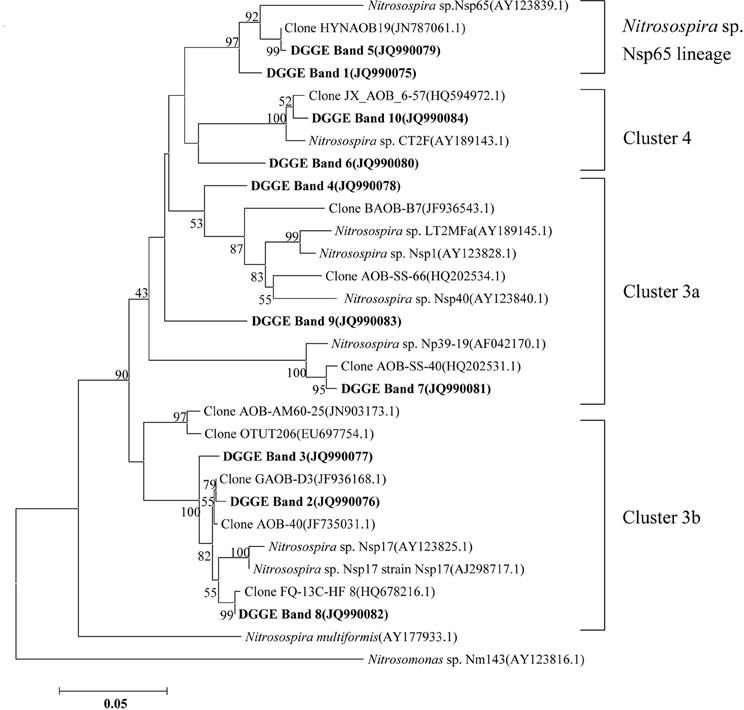

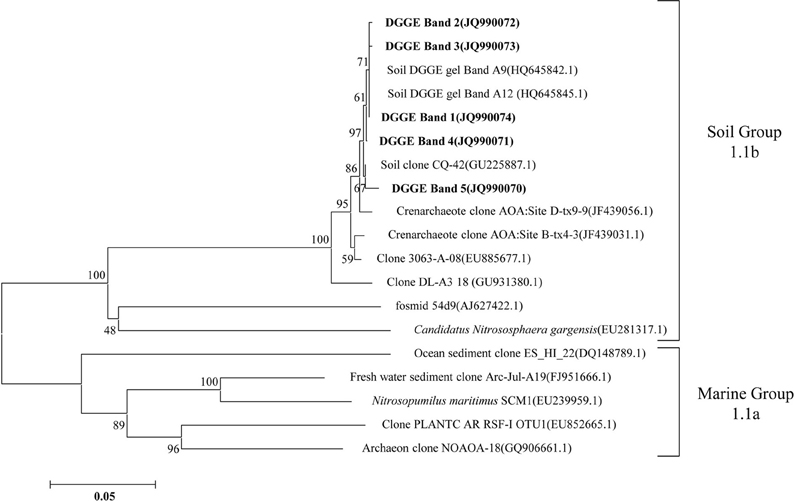

The compositions of the AOB and AOA communities were revealed by DGGE fingerprinting analyses of the bacterial and archaeal amoA genes in duplicate microcosms for the urea and (NH4)2SO4 treatments (Figures 5 and 6). Distinctly different DGGE fingerprints for the bacterial amoA genes were observed among the control treatment and the soil microcosms amended with different levels of nitrogenous fertilizers. Dominant AOB DGGE bands (1–10) were sequenced for phylogenetic analysis (Figure 7). Six DGGE bands (2–4 and 7–9) were affiliated with the Nitrosospira cluster 3 lineage, whereas bands 1 and 5 clustered with the taxonomically unclassified Nitrosospira sp. Nsp65 lineage. Additionally, DGGE bands 6 and 10 were related to Nitrosospira cluster 4. Comparisons of the DGGE patterns among the different treatments indicated that the relative intensities of DGGE bands 6 and 8 decreased upon the addition of higher levels of urea, whereas band 6 disappeared in the soil amended with 200 μg (NH4)2SO4 N/g.d.w.s. As for the AOA, 5 DGGE bands for the archaeal amoA gene were excised for sequencing (Figure 8). DGGE band 1 was either absent or the intensity of its band was lower in the soil microcosms treated with heavy fertilizations. Phylogenetic analyses indicated that all of the AOA sequences fall well within the soil group I.1b lineage.

Figure 5. DGGE fingerprints of the bacterial amoA gene in the soil microcosms amended with urea (A) and ammonium sulfate (B). The arrows indicate DGGE bands excised for sequencing. Zero represents the original soil sample, and all other designations are the same as in Figure 1. R1 and R2 represent duplicate microcosms.

Figure 6. DGGE fingerprints of the archaeal amoA gene in the soil microcosms amended with urea (A) and ammonium sulfate (B). The arrows indicate DGGE bands excised for sequencing. Zero represents the original soil sample, and all other designations are the same as those in Figure 1. R1 and R2 represent duplicate microcosms.

Figure 7. Neighbor-joining tree showing the relationships of the bacterial amoA genes retrieved from the DGGE bands (bold) in this study to those in the GenBank. The scale bar indicates 5 changes per 100 nucleotide acid positions. Bootstrap values (>40%) are indicated at branch points.

Figure 8. Neighbor-joining tree showing the relationships of the archaeal amoA genes retrieved from the DGGE bands (bold) in this study to those in the GenBank. The scale bar indicates 5 changes per 100 nucleotide acid positions. Bootstrap values (>40%) are indicated at branch points.

Discussion

Methane Oxidation Activity

The results of this study have revealed that CH4 oxidation activity in a paddy soil might be affected by nitrogenous fertilizations. CH4 oxidation was not significantly different among the microcosm treated with 0, 50 and 100 μg urea N/g.d.w.s. Similar results were observed for 0 and 50 μg (NH4)2SO4-N/g.d.w.s., indicating that the ammonium fertilizer had no significant effect on CH4 oxidation. These observations are largely consistent with previous findings (Dunfield et al., 1995; Delgado and Mosier, 1996; Dan et al., 2001). However, 200 and 400 μg urea N/g.d.w.s appeared to inhibit CH4 oxidation activity compared to other treatments. Interestingly, 200 μg (NH4)2SO4-N/g.d.w.s. also inhibited CH4 oxidation. These findings are in agreement with those reported by (Steudler et al., 1989; King and Schnell, 1994; Bosse et al., 1993; Gulledge et al., 1997; Van der Nat et al., 1997). The main mechanism by which nitrogenous fertilizers inhibits CH4 oxidation is thought to be ammonia, which competes with CH4 for the methane monooxygenases in MOB. Even though the affinity of MMO for CH4 is 600–1300-fold higher than its affinity for ammonia, excessively high concentrations of ammonium are known to substantially inhibit CH4 oxidation (Be'dard and Knowles, 1989). The results of this study support this mechanism because the inhibition of CH4 oxidation appeared to be intensified with higher concentrations of ammonium.

In this study, ammonium-based fertilizers displayed either an inhibitory effect or no effect on CH4 oxidation, which was dependent on the concentration of the applied fertilizers. To the contrary, Bodelier and co-workers (2000a,b) have elegantly demonstrated a stimulation of CH4 oxidation by ammonium fertilization in paddy soils. This observation might result from the absence of inorganic nitrogen, which would lead to an inactive and most likely non-growing methanotrophic community. Thus, the addition of ammonium-based fertilizers would relieve the nitrogen-limiting conditions and stimulate CH4 oxidation activity. It is likely that the soil used in this study was not constrained by the availability of N to support microbial growth. Therefore, the growth of methanotrophic communities was not restricted by the nitrogenous substrate, and no stimulation of CH4 oxidation activity was observed upon the addition of nitrogenous fertilizations. In addition to the soil's nitrogen status, our results also indicate a strong correlation between the concentration of the applied ammonium fertilizers and CH4 oxidation activity. Up to a certain concentration, ammonium-based fertilizers had no effect on CH4 oxidation; however, under higher concentrations, there was an inhibitory effect on the CH4 oxidation rate. CH4 oxidation in the paddy soils may have been inhibited when the concentration of urea/(NH4)2SO4 reached 200 μg N/g.d.w.s or above.

Nitrification Activity

The nitrification activity responded positively to nitrogenous fertilizations. All the urea- and (NH4)2SO4-treated microcosms displayed gradual increased productions of nitrate and nitrite over the incubation period upon the addition of nitrogenous fertilizers. Similar results have been reported by Avrahami et al. (2002) and Verhamme et al. (2011), that is, nitrification activity increased with increasing concentrations of ammonium in soil microcosms. Although a negative correlation between nitrification activity and CH4 oxidation activity was observed, it is interesting to note that the presence of CH4 appeared to have no adverse effect on nitrification activity in this study. We speculate that the stimulated nitrification activity might have led to a soil pH decline, as reported previously (Jia and Conrad, 2009). The acidification of the soil microcosms could have further inhibited CH4 oxidation activity by suppressing the growth of MOB in soil microcosms amended with higher concentrations of the nitrogenous fertilizers. In addition, the elevated concentrations of soil nitrate might have had an adverse effect on CH4 oxidation. Reay and Nedwell (2004) and Xu and Inubushi (2004) have shown a negative correlation between nitrate concentrations in soils and CH4 oxidation rates in coniferous and deciduous forest soils. However, the mechanism has yet to be determined. Several studies have suggested that cations associated with nitrate rather than nitrate itself are the main factors producing the inhibitory effect, but contrasting results have also been reported (Wang and Ineson, 2003). A comprehensive investigation of the microorganisms involved in nitrogen turnover, such as AOA and AOB, would be helpful in better understanding the interactions between ammonia oxidation and CH4 consumption in paddy soil.

Abundances of MOB, AOB, and AOA Gene Copy Number

Soil microcosms amended with 50 and 100 μg urea N/g.d.w.s. displayed an increased abundance of pmoA gene copies while a low abundance was observed in microcosms treated with 200 and 400 μg urea N/g.d.w.s. after 27 days of incubation, as compared to the control treatment. The pmoA gene copy number was higher in 0 and 100 μg ammonium sulfate N/g.d.w.s amended treatments compared to the 200 μg ammonium sulfate N/g.d.w.s amended microcosms, where the CH4 oxidation rate was higher in the 0 and 50 μg ammonium sulfate N/g.d.w.s than that of the 200 μg ammonium sulfate N/g.d.w.s amended microcosm. This result suggests that this suppressed CH4 oxidation activity was most likely attributable to the low abundance of methanotrophic communities in the soil microcosms that received heavy fertilizations.

Despite the fact that an apparently low abundance was measured in soil microcosms treated with 400 μg urea N/g.d.w.s. after a 27-day incubation, the bacterial amoA gene copy number was not significantly different among the microcosms treated with different levels of nitrogenous fertilizers. Similar results were obtained for the (NH4)2SO4 treatments. As for the AOA, the archaeal amoA gene copy numbers remained largely unchanged irrespective of the urea and ammonium sulfate–N addition levels. However, the treatment that received the highest N fertilizations of 400 μg urea N/g.d.w.s. had relatively lower amoA gene copy numbers. This finding is in agreement with previous results using a German agricultural soil (Jia and Conrad, 2009), semi-arid and temperate grassland in China (Shen et al., 2011), and a grazed grassland soil treated with high doses of urine-N input in New Zealand (Di et al., 2010).

Community Composition of MOB, AOB, and AOA

Distinct differences were found between the U-0 and U-400 treatments after four weeks of incubation, indicating that the MOB community was substantially altered upon the application of a higher amount of N-fertilizer. The soil microcosm amended with ammonium sulfate also displayed relative changes of the MOB community compared with the control treatment. Our results indicate that the type I MOB related to the Methylobacter, Methylomicrobium, and Methylococcus genera were less abundant than the type II MOB in the native soils studied. However, a relative increase of the type I MOB was observed in the soil microcosms amended with nitrogenous fertilizers while the type II MOB appeared to be inhibited. This observation is consistent with findings from forest and rice field soils (Mohanty et al., 2006). This result could be an effect of a competition for N between the type I and type II MOB during the incubations. With respect to the effects of the nitrogenous fertilizers on CH4 consumption, it appears that no consistent patterns can be generalized (Mohanty et al., 2006). Currently, the established inhibition mechanisms of CH4 oxidation by ammonium application are that the type I MOB benefit significantly more from the presence of inorganic nitrogen than the type II MOB, possibly because of the ability of type II MOB to fix molecular nitrogen (Graham et al., 1993; Bodelier et al., 2000b; Bodelier and Laanbroek, 2004). The rapid response of the type I MOB to N-addition may also be connected to nitrogen fixation, which is a capability that is widespread among MOB (Auman et al., 2001).

The effect of ammonium fertilizers on CH4 oxidation (stimulation or inhibition) obviously depends on the community's composition and, hence, on the biodiversity of the MOB present. Generally, it is assumed that CH4 consumption in a soil or sediment with a predominant type I MOB will not be affected by fertilizer application while CH4 uptake by a soil or sediment containing a predominant type II will be inhibited (Mohanty et al., 2006). Moreover, differentiation can also be expected within type I and II representatives. This scenario was clearly evident in the dominance of a specific type of MOB affiliated with Methylocella and Methylocystis in acid peat (Dedysh et al., 2001), a phylotype in association with Methylocystis and USCγ in periodically water-saturated gleyic soils (Knief et al., 2006) and Methylomonas-like MOBs in lake sediments (Auman and Lidstrom, 2002; Eller et al., 2005). In this study, the native soil was clearly dominated by type II MOB, which could have very likely been inhibited by higher levels of ammonium fertilizer.

The DGGE fingerprints of the bacterial amoA genes were altered by the addition of higher doses of nitrogenous fertilizers. A pairwise comparison of the DGGE patterns among the different treatments indicated that the relative intensities of DGGE bands 6 and 8 were significantly decreased within the soil microcosms containing higher levels of urea, whereas DGGE band 6 was absent in the soils that received 200 μg (NH4)2SO4-N/g.d.w.s. Phylogenetic analyses indicated that DGGE band 6 was most closely affiliated with the Nitrosospira cluster 4 group while DGGE band 8 clustered with the Nistrosospira cluster 3b group. We speculate that the AOB affiliated with DGGE bands 6 and 8 might not be the dominant ammonia oxidizers in the soils studied. It is very interesting to note that the dominant AOB DGGE bands were associated with Nistrosospira cluster 3 and the taxonomically unclassified Nitrosospira sp. Nsp65 lineage that could have been responsible for the stimulated nitrification activity observed in this study, which is consistent with the active ammonia oxidizers in an upland agricultural soil (Jia and Conrad, 2009). The interaction mechanisms between AOB and MOB remain unclear in a complex environment. For example, the contributions of MOB and AOB to ammonia oxidation and CH4 oxidation, respectively, and their possible interactions remain unresolved in complex environment (Bodelier, 2011). Furthermore, the discovery of AOA adds a new perspective to interactions between CH4 and ammonia oxidizers. AOA are very abundant and outnumber AOB in rice soils (Chen et al., 2008). However, it remains elusive as to whether CH4 oxidation could be affected by AOA in paddy soil and how AOA would compete with MOB for ammonium. Phylogenetic analyses demonstrated that archaeal ammonia oxidizers are dominated by AOA members within the soil Group I.1b. Although the DGGE fingerprints of the archaeal amoA genes displayed variations among the soil microcosms treated with different levels of nitrogenous fertilizers, such as DGGE band 1, this study provides no conclusive evidence that CH4 oxidation is linked to the AOA. Methodological developments to differentiate CH4 oxidation from ammonia oxidation under in situ conditions will be crucial for answering this question (Bodelier and Frenzel, 1999). It has very recently been shown that MOB can switch from CH4 oxidation to ammonia oxidation upon fertilizer addition by using stable C and N isotope probing (Acton and Baggs, 2011).

Conclusion

Different levels of nitrogenous fertilizers can affect the CH4 oxidation activity as well as the abundance and composition of MOB. Inhibitory effects on CH4 oxidation were demonstrated in soil microcosms amended with 200 μg urea N/g.d.w.s and above after 27 days of incubation. Similar results were obtained for ammonium sulfate-amended soil microcosms. The community structure of MOB changed in the soil microcosms amended with different levels of nitrogenous fertilizers. The native MOB in the background soil were dominated by type II; however, the addition of ammonium stimulated type I MOB. In addition, our study indicated strong nitrification in soil microcosms amended with nitrogenous fertilizers. Strong nitrification might lead to a pH decline, which may affect the niche differentiation of MOB. The interaction mechanisms among AOA, AOB, and MOB will require further investigation.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the National Science Foundation of China (40971153 and 41090281), the Knowledge Innovation Programs of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (KSCX2-EW-G-16 and KZCX2-YW-BR-06). We thank two anonymous reviewers for constructive comments that improve the manuscript greatly. Mr. M. Saiful Alam received a doctoral fellowship from the Graduate University of Chinese Academy of Sciences and China Scholarship Council.

References

Acton, S. D., and Baggs, E. M. (2011). Interactions between N application rate, CH4 oxidation and N2O production in soil. Biogeochemistry 103, 15–26.

Aronson, E. L., and Helliker, B. R. (2010). Methane flux in non-wetland soils in response to nitrogen addition: a meta-analysis. Ecology 91, 3242–3251.

Auman, A. J., and Lidstrom, M. E. (2002). Analysis of sMMO-containing type I methanotrophs in Lake Washington sediment. Environ. Microbiol. 4, 517–524.

Auman, A. J., Speake, C. C., and Lidstrom, M. E. (2001). nifH sequences and nitrogen fixation in type I and type II methanotrophs. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67, 4009.

Avrahami, S., Conrad, R., and Braker, G. (2002). Effect of soil ammonium concentration on N2O release and on the community structure of ammonia oxidizers and denitrifiers. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68, 5685–5692.

Be'dard, C., and Knowles, R. (1989). Physiology, biochemistry, and specific inhibitors of CH4, NH+4, and CO oxidation by methanotrophs and nitrifiers. Microbiol. Rev. 53, 68–84.

Bodelier, P. L. E. (2011). Interactions between nitrogenous fertilizers and methane cycling in wetland and upland soils. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustainability. 3, 379–388.

Bodelier, P. L. E., and Frenzel, P. (1999). Contribution of methanotrophic and nitrifying bacteria to CH4 and NH+4 oxidation in the rhizosphere of rice plants as determined by new methods of discrimination. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65, 1826–1833.

Bodelier, P. L. E., Hahn, A. P., Arth, I. R., and Frenzel, P. (2000a). Effects of ammonium based fertilisation on microbial processes involved in methane emission from soils planted with rice. Biogeochemistry 51, 225–257.

Bodelier, P. L. E., Roslev, P., Henckel, T., and Frenzel, P. (2000b). Stimulation by ammonium-based fertilizers of methane oxidation in soil around rice roots. Nature 403, 421–424.

Bodelier, P. L. E., and Laanbroek, H. J. (2004). Nitrogen as a regulatory factor of methane oxidation in soils and sediments. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 47, 265–277.

Bosse, U., Frenzel, P., and Conrad, R. (1993). Inhibition of methane oxidation by ammonium in the surface layer of a littoral sediment. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 13, 123–134.

Chen, X. P., Zhu, Y. G., Xia, Y., Shen, J. P., and He, J. Z. (2008). Ammonia-oxidizing archaea: important players in paddy rhizosphere soil? Environ. Microbiol. 10, 1978–1987.

Conrad, R. (2004). “Methanogenic microbial communities associated with aquatic plants,” in Plant Surface Microbiology, eds A. Varma, L. Abbott, D. Werner, and R. Hampp (Berlin, Germany: Springer), 35–50.

Costello, A. M., and Lidstrom, M. E. (1999). Molecular characterization of functional and phylogenetic genes from natural populations of methanotrophs in lake sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65, 5066–5074.

Crutzen, P. J. (1995). “The role of methane in atmospheric chemistry and climate,” in Proceedings of the Eighth International Symposium on Ruminant Physiology, Ruminant Physiology: Digestion, Metabolism, Growth and Reproduction, eds W. Von Engelhardt, S. Leonhard-Marek, G. Breves, and D. Giesecke (Stuttgart, Germany: Ferdinand Enke Verlag), 291–316.

Dan, J., Krüger, M., Frenzel, P., and Conrad, R. (2001). Effect of a late season urea fertilization on methane emission from a rice field in Italy. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 69, 69–80.

Dedysh, S. N., Derakshani, M., and Liesack, W. (2001). Detection and enumeration of methanotrophs in acidic Sphagnum peat by 16S rRNA fluorescence in situ hybridization, including the use of newly developed oligonucleotide probes for Methylocella palustris Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67, 4850–4857.

Delgado, J. A., and Mosier, A. R. (1996). Mitigation alternatives to decrease nitrous oxides emissions and urea-nitrogen loss and their effect on methane flux. J. Environ. Qual. 25, 1105–1111.

Di, H. J., Cameron, K. C., Shen, J. P., Winefield, C. S., O'Callaghan, M., Bowatte, S., and He, J. Z. (2010). Ammonia oxidizing bacteria and archaea grow under contrasting soil nitrogen conditions. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 72, 386–394.

Dunfield, P., and Knowles, R. (1995). Kinetics of inhibition of methane oxidation by nitrate, nitrite and ammonium in a humisol. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61, 3129–3135.

Dunfield, P. F., Topp, E., Archambault, C., and Knowles, R. (1995). Effect of nitrogen fertilizers and moisture-content on CH4 and N2O fluxes in a humisol-measurements in the field and intact soil cores. Biogeochemistry 29, 199–222.

Eller, G., Deines, P., Grey, J., Richnow, H.-H., and Kruger, M. (2005). Methane cycling in lake sediments and its influence on chironomid larval δ13C. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 54, 339–350.

Francis, C. A., Roberts, K. J., Beman, J. M., Santoro, A. E., and Oakley, B. B. (2005). Ubiquity and diversity of ammonia-oxidizing archaea in water columns and sediments of the ocean. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 14683–14688.

Graham, D. W., Chaudhary, J. A., Hanson, R. S., and Ranold, G. A. (1993). Factors affecting competition between type 1 and type 2 methanotrophs in two-organism, continuous-flow reactors. Microb. Ecol. 25, 1–17.

Griffiths, R. I., Whiteley, A. S., O'Donnell, A. G., and Bailey, M. J. (2000). Rapid method for coextraction of DNA and RNA from natural environments for analysis of ribosomal DNA- and rRNA-based microbial community composition. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66, 5488–5491.

Groot, T. T., VanBodegom, P. M., Harren, F. J. M., and Meijer, H. A. J. (2003). Quantification of methane oxidation in the rice rhizosphere using 13C-labelled methane. Biogeochemistry 64, 355–372.

Gulledge, J., Doyle, A. P., and Schimel, J. P. (1997). Different NH+4 inhibition patterns of soil CH4 –oxidizer populations across sites. Soil Biol. Biochem. 29, 13–21.

Houghton, J. T., Ding, Y., Griggs, D. J., Noguer, M., Van der Linden, P. J., and Xiaosu, D. (eds.). (2001). Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cam-bridge: Cambridge University Press.

IPCC, (2007). “Climate change 2007: the physical science basis,” in Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, eds S. Solomon, D. Qin, M. Manning, Z. Chen, M. Marquis, K. B. Averyt, M. Tignor, and H. L. Miller (Cambridge, UK; New York, NY: Cambridge University Press), 996.

Jia, Z., and Conrad, R. (2009). Bacteria rather than Archaea dominate microbial ammonia oxidation in an agricultural soil. Environ. Microbiol. 11, 1658–1671.

Khush, G. S. (2005). What it will take to Feed 5.0 Billion Rice consumers in 2030. Plant Mol. Biol. 59, 1–6.

King, G. M., and Schnell, S. (1994). Effect of increasing atmospheric methane concentration on ammonium inhibition of soil methane consumption. Nature 370, 282–284.

Knief, C., Kolb, S., Bodelier, P. L. E., Lipski, A., and Dunfield, P. (2006). The active methanotrophic community in hydromorphic soils changes in response to changing methane concentration. Environ. Microbiol. 8, 321–333.

Krüger, M., Eller, G., Conrad, R., and Frenzel, P. (2002). Seasonal variation in pathways of CH4 oxidation in rice fields determined by stable carbon isotopes and specific inhibitors. Glob. Change Biol. 8, 265–280.

Krüger, M., and Frenzel, P. (2003). Effects of N-fertilization on CH4 oxidation and production, and consequences for CH4 emissions from microcosms and rice fields. Glob. Change Biol. 9, 773–784.

Lelieveld, J., Crutzen, P. J., and Dentener, F. J. (1998). Changing concentrations, lifetime and climate forcing of atmospheric methane. Tellus 50B, 128–150.

Liu, D., Ding, W., Jia, Z., and Cai, Z. (2011). Relation between methanogenic archaea and methane production potential in selected natural wetland ecosystems across China. Biogeosciences 8, 329–338.

Mohanty, S. R., Bodelier, P. L. E., Floris, V., and Conrad, R. (2006). Differential effects of nitrogenous fertilizers on methane-consuming microbes in rice field and forest soils. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 1346–1354.

Nicolaisen, M. H., and Ramsing, N. B. (2002). Denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) approaches to study the diversity of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria. J. Microbiol. Methods 50, 189–203.

Reay, D. S., and Nedwell, D. B. (2004). Methane oxidation in temperate soils: effects of inorganic N. Soil Biol. Biochem. 36, 2059–2065.

Rigby, M., Prinn, R. G., Fraser, P. J., Simmonds, P. G., Langenfelds, R. L., Huang, J., Cunnold, D. M., Steele, L. P., Krummel, P. B., Weiss, R. F., O'Doherty, S., Salameh, P. K., Wang, H. J., Harth, C. M., Muhle, J., and Porter, L. W. (2008). Renewed growth of atmospheric methane. Geophys. Res. Lett. 35, L22805.

Rodhe, H. (1990). A comparison of the contribution of various gases to the greenhouse effect. Science 248, 1217–1219.

Rotthauwe, J., Witzel, K., and Liesack, W. (1997). The ammonia monooxygenase structural gene amoA as a functional marker: molecular fine-scale analysis of natural ammonia-oxidizing populations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63, 4704–4712.

Shen, X. Y., Zhang, L. M., Shen, J. P., Li, L. H., Yuan, C. L., and He, J. Z. (2011). Nitrogen loading levels affect abundance and composition of soil ammonia oxidizing prokaryotes in semiarid temperate grassland. J. Soils Sediments 11, 1243–1252.

Steudler, P. A., Bowden, R. D., Mellilo, J. M., and Aber, J. D. (1989). Influence of nitrogen fertilization on methane uptake in temperate forest soil. Nature 341, 314–316.

Tamura, K., Dudley, J., Nei, M., and Kumar, S. (2007). MEGA4, molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 1596–1599.

Thompson, J. D., Gibson, T. J., Plewniak, F., Jeanmougin, F., and Higgins, D. G. (1997). The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 4876–4882.

Van der Nat, F. J. W. A., DeBrouwer, J. F. C., Middelburg, J. J., and Laanbroek, H. J. (1997). Spatial distribution and inhibition by ammonium of methane oxidation in intertidal freshwater marshes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63, 4734–4740.

Verhamme, D. T., Prosser, J. I., and Nicol, G. W. (2011). Ammonia concentration determines differential growth of ammonia-oxidising archaea and bacteria in soil microcosms. ISME J. 5, 1067–1071.

Wang, J. S., Logan, J. A., McElroy, M. B., Duncan, B. N., Megretskaia, I. A., and Yantosca, R. M. (2004). A 3-D model analysis of the slowdown and interannual variability in the methane growth rate from 1988 to 1997 [Review]. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 18:B3011. doi: 10.1029/2003GB002180.

Wang, Z. P., and Ineson, P. (2003). Methane oxidation in a temperate coniferous forest soil: effects of inorganic N. Soil Biol. Biochem. 35, 427–433.

Wu, Y., Lu, L., Wang, B., Lin, X., Zhu, J., Cai, Z., Yan, X., and Jia, Z. (2011). Long-term field fertilization significantly alters the community structure of ammonia-oxidizing Bacteria rather than Archaea in a paddy soil. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 75, 1431–1439.

Xu, X., and Inubushi, K. (2004). Effects of N sources and methane concentrations on methane uptake potential of a typical coniferous forest and its adjacent orchard soil. Biol. Fertil. Soils 40, 215–221.

Appendix

Figure A1. Relationships among the concentration of CH4 remained in the headspace, the amount of NO−2 and NO−3-N and the copy number of pmoA genes in the soil microcosms amended with urea and ammonium sulfate after 27 days of incubation. The black line is the linear regression line between two parameters. The P values for panel (A) 0.001, (B) 0.055, and (C) 0.064.

Keywords: methane oxidation, nitrogenous fertilizers, particulate methane monooxygenase gene pmoa, nitrification activity, paddy soil

Citation: Alam MS and Jia Z (2012) Inhibition of methane oxidation by nitrogenous fertilizers in a paddy soil. Front. Microbio. 3:246. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00246

Received: 15 November 2011; Accepted: 18 June 2012;

Published online: 04 July 2012.

Edited by:

Paul Bodelier, Netherlands Institute of Ecology (NIOO-KNAW), NetherlandsReviewed by:

Brajesh Singh, University of Western Sydney, AustraliaAnne Daebeler, Netherlands Institute of Ecology (NIOO-KNAW), Netherlands

Copyright © 2012 Alam and Jia. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in other forums, provided the original authors and source are credited and subject to any copyright notices concerning any third-party graphics etc.

*Correspondence: Zhongjun Jia, State Key Laboratory of Soil and Sustainable Agriculture, Institute of Soil Science, Chinese Academy of Sciences, East Beijing Road, No. 71, Xuan-Wu District, Nanjing, 210008, Jiangsu Province, P.R. China. e-mail: jia@issas.ac.cn