- 1Department of Microbiology, University of Georgia, Athens, GA, USA

- 2Department of Botany and Microbiology, University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK, USA

- 3Institute for Environmental Genomics, University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK, USA

Thermal environments have island-like characteristics and provide a unique opportunity to study population structure and diversity patterns of microbial taxa inhabiting these sites. Strains having ≥98% 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity to the obligately anaerobic Firmicutes Thermoanaerobacter uzonensis were isolated from seven geothermal springs, separated by up to 1600 m, within the Uzon Caldera (Kamchatka, Russian Far East). The intraspecies variation and spatial patterns of diversity for this taxon were assessed by multilocus sequence analysis (MLSA) of 106 strains. Analysis of eight protein-coding loci (gyrB, lepA, leuS, pyrG, recA, recG, rplB, and rpoB) revealed that all loci were polymorphic and that nucleotide substitutions were mostly synonymous. There were 148 variable nucleotide sites across 8003 bp concatenates of the protein-coding loci. While pairwise FST values indicated a small but significant level of genetic differentiation between most subpopulations, there was a negligible relationship between genetic divergence and spatial separation. Strains with the same allelic profile were only isolated from the same hot spring, occasionally from consecutive years, and single locus variant (SLV) sequence types were usually derived from the same spring. While recombination occurred, there was an “epidemic” population structure in which a particular T. uzonensis sequence type rose in frequency relative to the rest of the population. These results demonstrate spatial diversity patterns for an anaerobic bacterial species in a relative small geographic location and reinforce the view that terrestrial geothermal springs are excellent places to look for biogeographic diversity patterns regardless of the involved distances.

Introduction

The Kamchatka Peninsula is located on the northern side of the Kurile–Kamchatka arc and is considered one of the outstanding volcanic regions in the world. The peninsula contains many active volcanoes and numerous related geothermal features including terrestrial geothermal springs, fumaroles, and geysers (Karpov and Naboko, 1990). The Uzon Caldera in Kamchatka is the result of a giant explosion of a stratovolcano during the mid-Pleistocene and the region now contains an array of geothermal features in close proximity (Karpov and Naboko, 1990). A variety of novel thermophilic microorganisms have been isolated from geothermal springs of Kamchatka including Thermoanaerobacter taxa. Three of the 14 species presently classified within the Thermoanaerobacter genus (May 2013, http://www.bacterio.cict.fr/t/thermoanaerobacter.html) were isolated from hot springs of Kamchatka: Thermoanaerobacter uzonensis (Wagner et al., 2008), Thermoanaerobacter siderophilus (Slobodkin et al., 1999), and Thermoanaerobacter sulfurophilus (Bonch-Osmolovskaya et al., 1997). Furthermore, diverse and unique microbial communities within geothermal springs of the Uzon Caldera have been revealed through 16S rRNA gene clone libraries (Burgess et al., 2011), and high-throughput sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene V6 hypervariable region (D. E. Crowe, pers. communication).

Terrestrial hot springs are frequently regarded as having insular characteristics: they are often well-defined and can be geographically isolated. In addition, geothermal springs in close proximity may have markedly different geochemical properties. For these reasons the comparison of microorganisms from different hot springs provides the opportunity to investigate the spatial patterns of biodiversity. Island-like environments also provide an excellent opportunity to assess gene flow between locations. Understanding characteristics such as genetic variation and gene migration within microbial communities then provides insight into how variations develop and are maintained in natural populations. Biogeographic diversity patterns have been observed for some microorganisms inhabiting terrestrial hot springs, including cyanobacteria (Papke et al., 2003) Rhodothermus (Petursdottir et al., 2000), Thermus (Hreggvidsson et al., 2006), Sulfurihydrogenibium (Takacs-Vesbach et al., 2008), and Sulfolobus (Whitaker et al., 2003). Since the 16S rRNA gene sequence is slowly evolving and therefore of little use in intraspecies comparisons (Cooper and Feil, 2004), reports that describe biogeographic patterns within a microbial species have often focused on sequencing and analysis of more rapidly evolving non-coding or protein-coding loci (Whitaker, 2006). In some studies multilocus sequence analysis (MLSA), a technique that utilizes the sequencing of multiple gene fragments to assess the phylogeny and population structure of a group of related strains (Gevers et al., 2005), has been utilized to analyze the spatial diversity patterns of a microbial group (Whitaker et al., 2003; Papke et al., 2007).

Gene flow between sites is significant because of the ensuing potential for recombination within a population. While homologous recombination is reported to occur at varying rates within microbial populations, it has attracted attention because of its importance to fields such as microbial systematics, ecology, population genetics, and evolution (Achtman and Wagner, 2008). As Papke et al. (2007) state, there are potentially two contrasting effects of homologous recombination within a population. Homologous recombination acts as a diversifying force when a pair of strains have strikingly different alleles with one gene, while the remaining genes are identical. Conversely, homologous recombination is a cohesive force when divergent strains share a single identical allele. Considering taxa from terrestrial hot springs, the moderately thermophilic cyanobacterium Mastigocladus laminosus was found to be recombining (Miller et al., 2007), as was the population of the aerobic archaeum Sulfolobus from the Mutnovsky region of Kamchatka (Whitaker et al., 2005). However, multilocus enzyme electrophoresis of Rhodothermus marinus isolates from Iceland indicated that the species is clonal and that recombination occurs rarely (Petursdottir et al., 2000).

Strains of T. uzonensis, an obligately anaerobic species within the Firmicutes phylum, were repeatedly isolated from geothermal spring samples collected from the Uzon Caldera region of Kamchatka, Far East Russia. The isolation of these microorganisms prompted an initial question of whether spatial patterns of diversity would be observed for this species within this relatively narrow geographical location. To address this question MLSA was performed with 106 strains of T. uzonensis from seven pools separated by 140–1600 m within the Uzon Caldera region of Kamchatka, Far East Russia. Because the occurrence and frequency of recombination within and between subpopulation can strongly affect whether biogeographic patterns are observed, we also assessed the influence of homologous recombination on this taxon in this region.

Materials and Methods

Sample Collection and Isolation of Thermoanaerobacter Strains

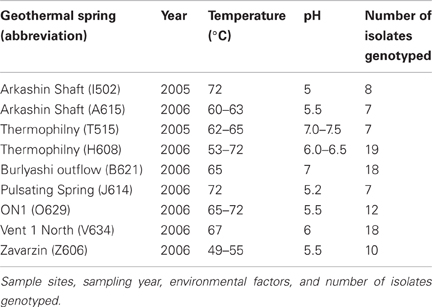

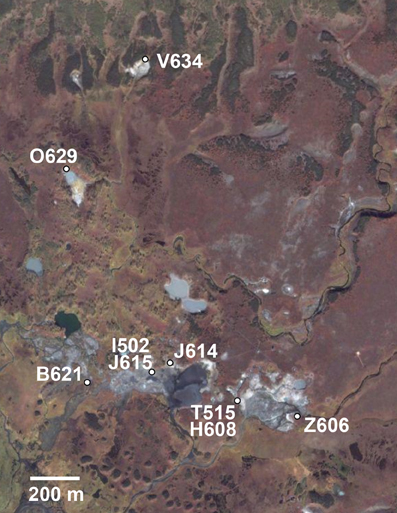

During August 2005 and August 2006, mixed water and sediment samples were collected from geothermal springs within the Uzon Caldera during the Kamchatka Microbial Observatory field seasons (Figure 1). The samples collected had temperature between 49–75°C and pH 5–7.5 (Table 1). Water and sediment samples were transferred to sterilized 100 ml bottles, filled to the brim, sealed with butyl rubber stoppers, transferred to Athens, GA, USA, and stored at 4°C. In the laboratory, 1 ml of mixed water/sediment was transferred to 50 ml Wheaton serum bottles containing 20 ml of an anaerobic mineral medium (Wagner et al., 2008) supplemented with 1 g·l−1 glucose, 0.5 g·l−1 yeast extract, and 50 mM thiosulfate. Enrichment cultures were incubated at 62°C for 48 h. A 10−1 dilution was prepared, streaked onto a 2.15% (w/v) agar plate of the same medium composition, and then incubated anaerobically at 62°C for 48 h. A single colony was selected and re-streaked for isolation on a new agar plate a minimum of two times. Each isolate was derived from its own enrichment culture. To assess culture purity following the repeated single colony isolations, electropherograms of the protein coding loci and 16S rRNA gene were manually examined for correct base calling. Sequences with ambiguous sites were re-sequenced or colonies were isolated anew and loci re-sequenced. Within this study the entire set of isolates was considered the population while the collection of strains derived from a single hot spring was regarded as a subpopulation.

Figure 1. Location of sample sites in the Uzon Caldera for 106 T. uzonensis strains used in this study. Hot spring positions and abbreviations (Table 1) were overlaid on the satellite image. Image © 2009 Google—Imagery © 2009 DigitalGlobe, GeoEye, Map data © 2009 Geocentre Consulting.

PCR Amplification of the 16S rRNA Gene and Protein Coding Loci

Genomic DNA was isolated with the UltraClean Microbial DNA Isolation kit (Mo Bio). The 16S rRNA gene sequence was amplified with the 27F and 1492R primers (Lane, 1991) using PrimeSTAR HS DNA Polymerase (Takara). The thermal cycler conditions for amplification were: 30 cycles of 98°C for 10 s, 58°C for 5 s, and then 72°C for 90 s. Purification of the amplification product and the subsequent sequencing reaction was performed by Macrogen USA (Rockville, MD).

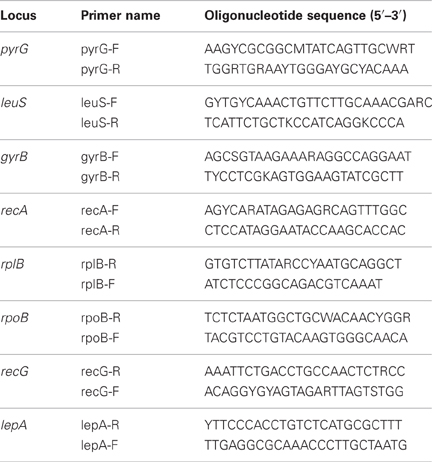

The universally conserved protein coding genes analyzed in this study were selected from those suggested by Santos and Ochman (2004); gyrB, lepA, leuS, pyrG, recA, recG, rplB, and rpoB. Primers for the amplification of universally conserved protein coding genes from Thermoanaerobacter isolates (Table 2) were designed from the genes of representatives of the family Thermoanaerobacteracae with sequenced genomes; Thermoanaerobacter pseudethanolicus strain 39E (Refseq: NC_010321), Caldanaerobacter subterraneus subsp. tengcongensis strain MB4 (Refseq: NC_003869). Thermoanaerobacter sp. X514 (Refseq: NC_010320), and Carboxydothermus hydrogenoformans Z-2901 (Refseq: NC_007503).

Table 2. Oligonucleotide primers for the amplification of universally conserved protein coding genes from Thermoanaerobacter uzonensis isolates.

The universally conserved protein coding genes were amplified with Phusion High-Fidelity polymerase PCR Master Mix with HF Buffer (New England Biolabs). Amplification was performed in a Mastercycler ep Gradient thermal cycler (Eppendorf). Conditions for the amplification of the gyrB, lepA, leuS, pyrG, recG, and rpoB loci were: 98°C for 10 s; then 30 cycles of 98°C for 1 s, 56°C for 5 s, and 72°C for 20 s; and then 72°C for 1 min. Conditions for the amplification of the recA and rplB loci were: 98°C for 10 s; then 30 cycles of 98°C for 1 s, 56°C for 5 s, and 72°C for 12 s; and then 72°C for 1 min. Purification of the amplification product and the subsequent sequencing reaction was performed by Macrogen USA (Rockville, MD). All nucleotide sequences were deposited to GenBank and are available through the Entrez PopSet database; accession numbers for the different loci from T. uzonensis are: 16S rRNA gene, 301133600; pyrG, 306992496; gyrB, 310780896; rplB, 304564022; recG, 306992180; recA, 304564400; rpoB, 304561479; lepA, 302120473; and leuS, 301133848.

Analysis of Sequence Diversity

The 16S rRNA gene sequences were aligned and initially analyzed with Sequencher 4.1 (Gene Codes). Multiple sequence alignments were prepared with NAST (Desantis et al., 2006) through the GreenGenes web application (http://greengenes.lbl.gov/). Multiple sequence alignments of the protein coding gene sequences were prepared with ClustalW (Larkin et al., 2007). Protein-coding loci sequences were initially aligned with the homologous gene sequences from the related Thermoanaerobacteracae with sequenced genomes and then checked for spurious insertion or deletions. For every 96-well plate sequenced the locus from one isolate was sequenced multiple times to check that the DNA sequencing was accurate.

Sequence heterogeneity was determined using DnaSP (Rozas and Rozas, 1999) or MEGA 4.1 (Tamura et al., 2007). Characteristics assessed included the total number of polymorphic nucleotide sites, S; the number of alleles for the gene sequence loci, na; and the average number of nucleotide substitutions per site, Pi. Taking into account the deduced primary protein sequence, the number of variable amino acid sites was determined for each locus. Genetic diversity, H, was calculated as described by Haubold and Hudson (2000), using the LIAN 3.5 web server (http://adenine.biz.fh-weihenstephan.de/cgi-bin/lian/lian.cgi.pl). This metric was calculated for each protein-coding locus taking into consideration all 106 T. uzonensis isolates and for the set of isolates from each hot spring.

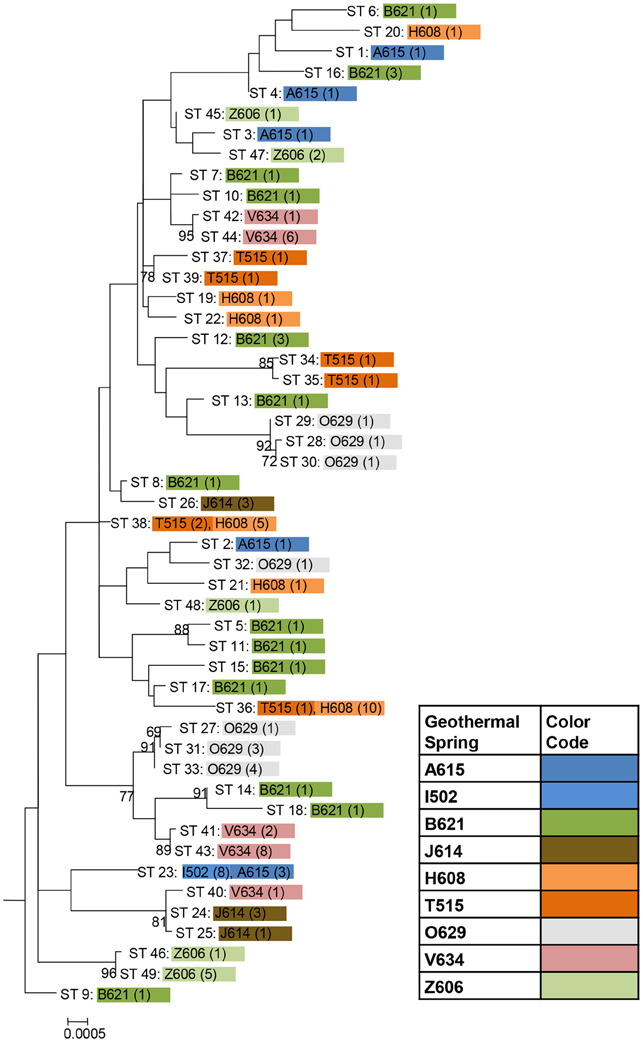

A phylogenetic tree based on concatenates of the eight protein coding loci was prepared considering the 49 unique genotypes observed among the set of 106 T. uzonensis strains. The phylogenetic analysis was performed in MEGA 5 (Tamura et al., 2011). A concatenated sequence with the same protein coding gene sequences from Thermoanaerobacter italicus Ab9T (Hemme et al., 2010) was included in the analysis as an outgroup. Nucleotide substitution models were evaluated and the model having the lowest goodness-of-fit Bayesian Information Criterion value was used to construct a tree using the maximum likelihood method. The initial tree for the maximum likelihood analysis was constructed automatically and the Nearest-Neighbor-Interchange heuristic search method was used to search for topologies that fit the data better. Reliability of the tree topology was assessed with the bootstrap method using 100 replications.

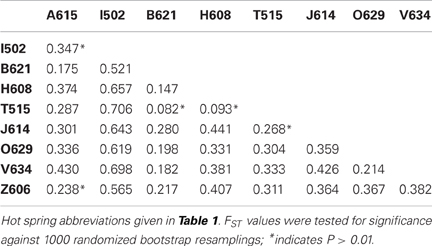

Calculating FST Values and Assessing the Relationship between Divergence and Spatial Separation

Pairwise FST values between T. uzonensis subpopulations from different hot springs were calculated with Arlequin 3.5 (Excoffier and Lischer, 2010), using concatenates of the eight protein-coding loci. FST values were tested for significance against 1000 randomized bootstrap resamplings. The relationship between the genetic divergence, based on nucleotide p-distance from concatenates of the eight protein-coding loci, and spatial separation was examined by calculating Spearman's rho rank correlation value, and the significance level of the Spearman's rho statistic, using the RELATE subprogram within Primer v6 (PRIMER-E Ltd).

Assessing Recombination within the T. uzonensis Population

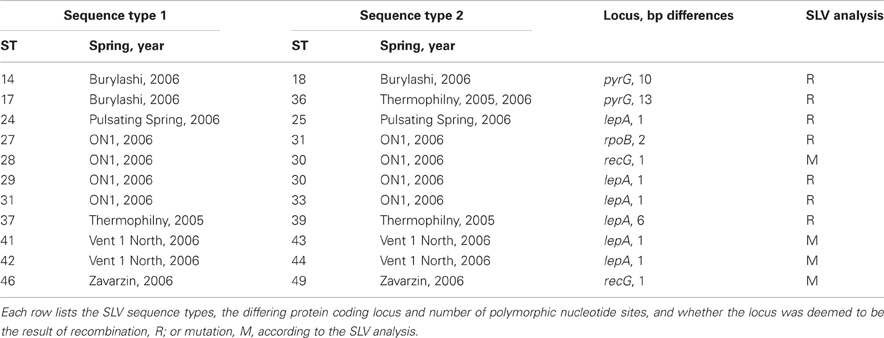

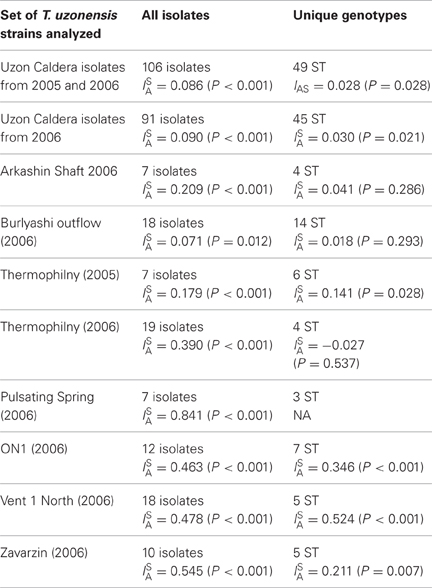

For a protein-coding locus, each different allele was assigned a number and the eight-loci sequence type for each isolate was tabulated. The influence of recombination on the population was first assessed by calculating the standardized index of association, ISA, to determine the randomness of the distribution of alleles (Haubold and Hudson, 2000). ISA values were calculated considering all 106 isolates and considering only the 91 strains isolated from samples collected in 2006. ISA values were also calculated considering the 49 unique sequence types from 2005 and 2006, as well as the 45 unique genotypes from 2006. Lastly, ISA values were calculated for each hot spring subpopulation taking into account all isolates and unique genotypes. Recombination in the T. uzonensis population was also assessed by examination of single locus variant (SLV) genotypes as described by Feil et al. (2000). Here, SLV genotypes were compiled and the sequence diversity for the variable loci were tabulated. If the variant allele differed by only single nt it was considered a point mutation. The allele was considered to have been the result of homologous recombination if it differed by multiple nt substitutions, or was observed multiple times in the dataset.

Results

Isolation of Thermoanaerobacter Strains

Anaerobic thermophilic strains were isolated from mixed water and sediment samples collected at seven different geothermal springs in the Uzon Caldera. In total, 106 isolates, between seven and 19 from each hot spring sampled, were analyzed by MLSA (Table 1). From 101 strains, the near full-length 16S rRNA gene sequence (≥1337 bp) was obtained and a comparison of the 16S rRNA gene sequence from these isolates revealed ≥98% 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity to each other and to the Thermoanaerobacter uzonensis type strain JW/IW010T (Wagner et al., 2008). The geothermal springs from which strains were obtained were separated by at most 1600 m (Figure 1). Each isolate was derived from its own enrichment culture. Hot springs yielding T. uzonensis isolates had temperatures of 49–75°C, measured at the location sampled, and circumneutral pH values (Table 1). Attempts to obtain isolates from two additional springs within the Uzon Caldera, “Oil Pool” (75°C, pH 4) and “K4 Well” (60°C; above 100°C in the 16 m deep well shaft, pH 7), were unsuccessful even though 12 or more enrichments where prepared from each sample. The type strain of T. uzonensis, JW/IW010T, was not included in the MLSA study since it was isolated from a hot spring which at the time of this study had disappeared.

Protein-Coding Loci Heterogeneity

The protein coding genes used in this study were among those recommended by Santos and Ochman (2004): DNA gyrase subunit B (gyrB), GTP-binding protein LepA (lepA), leucyl-tRNA synthetase (leuS), CTP synthase (pyrG), bacterial DNA recombination protein RecA (recA), ATP-dependent DNA helicase RecG (recG), 50S ribosomal protein L2 (rplB), and RNA polymerase subunit B (rpoB). The genes are distributed throughout the sequenced genomes of the Thermoanaerbacteracae (Hemme et al., 2010; detailed data not shown). To minimize the inclusion of apparent sequence heterogeneity due to DNA sequencing errors the protein-coding loci were amplified with Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase in HF Buffer (New England BioLabs, Inc).

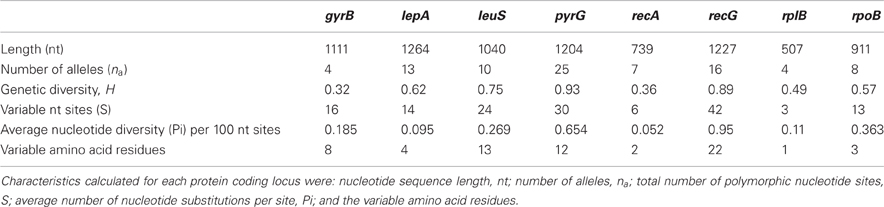

There were 148 variable sites from a total of 8003 bp in common across the eight protein-coding loci. All loci were polymorphic, however, the amount of variation at each locus differed (Table 3). For example, the number of variable nucleotide sites (S) observed for a locus varied from 3 for the rplB locus, to 42 for the recG locus. The deduced primary protein sequence revealed that most nucleotide substitutions were synonymous (Table 3).

Table 3. Characteristics of eight protein coding loci examined from the set of 106 T. uzonensis strains isolated from hot springs of the Uzon Caldera.

Genetic Differentiation of T. uzonensis Subpopulations

Genetic differentiation of the subpopulations from different hot spring was assessed by calculation of the pairwise FST values (Table 4). The FST values ranged from 0.082 to 0.706, and most values were found to be significant based on a bootstrap resampling test. Two of the five comparisons that were found to not be significantly different were the comparisons between Arkashin over multiple years and Thermophilny over multiple years.

Hot springs from which T. uzonensis isolates were derived were separated by distances that varied from about 140–1600 m (Figure 1), measured using a QuickBird (DigitalGlobe) satellite image (D. E. Crowe, personal communication). The relationship between the spatial separation of the hot springs and the genetic divergence of the T. uzonensis isolates was assessed by calculation of the Spearman's rank correlation coefficient: rho = 0.086, significance level of sample statistic: 0.83%.

Distribution of Alleles and Genotypes

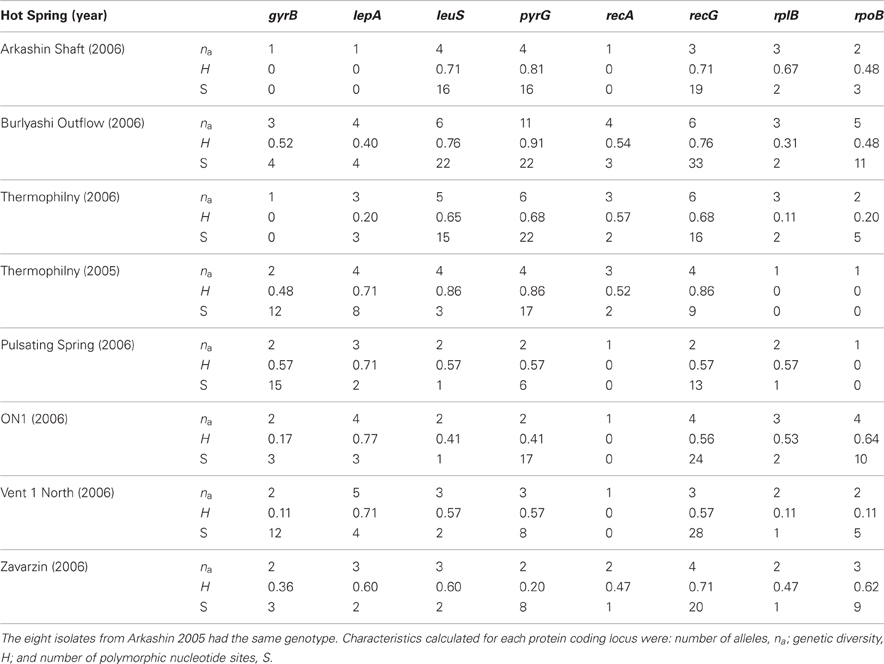

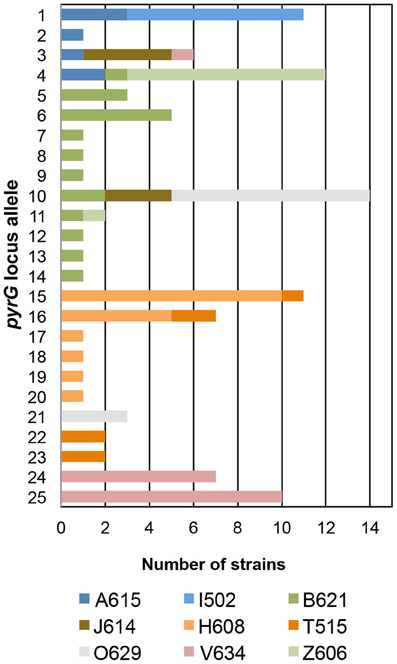

In the T. uzonensis population, the number of alleles at a particular protein-coding locus varied from 4 (rplB and gyrB) to 25 (pyrG). The genetic diversity, H, varied from 0.32 for gyrB to 0.93 for pyrG for the individual protein-coding loci (Table 3) and the average was 0.62. Correspondently, some alleles were found in a high proportion of the T. uzonensis population, e.g., gyrB allele 1, 82.1%; recA allele 1, 79.2%; and rplB allele 3, 67.9% (detailed data not shown). The distribution of alleles within a hot spring subpopulation was also examined. The seven isolates from Arkashin Shaft 2006 shared the same gyrB, lepA, and recA allele, but had comparatively high variation at the leuS, pyrG, and recG loci (Table 5). Among the 18 T. uzonensis isolates from Thermophilny 2006, there was a single gyrB locus allele, while the other seven loci were variable. All of the isolates from Arkashin Shaft 2005 had the same protein-coding loci sequence type, whereas considerable variation was found at all loci from the set of the Burlyashi outflow isolates (Table 5). Occasionally a particular allele was only observed within the T. uzonensis subpopulation from one hot spring and this was especially evident at the pyrG locus (Figure 2). For example, pyrG alleles 24 and 25 were only found in isolates from Vent 1 North (closest spring analyzed was ON1, approximately 530 m away), pyrG alleles 15 and 16 were only in strains from Thermophilny isolated in 2005 and 2006 (closest spring examined was Zavarzin, about 210 m distant), and pyrG allele 1 was only found in T. uzonensis strains from Arkashin in both 2005 and 2006 (closest spring analyzed, Pulsating Spring about 140 m away).

Table 5. Characteristics of protein coding loci examined from T. uzonensis subpopulations from different hot springs in the Uzon Caldera.

Figure 2. Distribution of pyrG alleles among T. uzonensis isolates. Bars are color coded and correspond to the hot spring from which the T. uzonensis isolates were derived. Geothermal spring abbreviations are given in Table 1.

Among the 106 T. uzonensis strains there were 49 unique sequence types (STs, Table 6). A majority of the STs, 35 of the 49, were unique to a single isolate and at most a sequence type was held by 11 isolates (STs 23 and 36; Table 6). Within the Uzon Caldera, isolates with identical genotypes were, in all instances, derived from the same hot springs. T. uzonensis isolates were obtained from samples collected at the Arkashin and Thermophilny springs in 2005 and 2006 and for both springs, strains with the same allelic profile were obtained over the 2 years. There were 11 pairs of SLVs among the 49 genotypes. Of these SLVs pairs, 10 were of genotypes held by isolates from the same hot spring (Table 7). The phylogenetic tree inferred from concatenates of the protein coding loci showed that genotypes of strains isolated from the same geothermal spring occasionally clustered together (Figure 3). Most bootstrap values were below 50%, which indicated minimal reliability in the tree topology.

Figure 3. Phylogenetic tree based on concatenates of the eight protein coding loci from the 49 unique sequence types among 106 T. uzonensis strains. ST designations match those given in Table 6 and are color coded according to hot spring origin. The number of strains having the particular ST is given in parentheses. Hot spring abbreviations are given in Table 1. The maximum likelihood tree was constructed using the Hasegawa-Kishino-Yano model with a rates among sites setting of gamma distributed with invariant sites. Only bootstrap proportions of 50 or higher are included on the tree. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site.

Assessing the Influence of Recombination on the T. uzonensis Population of the Uzon Caldera

The influence of recombination on the T. uzonensis population structure was assessed by calculating the standardized index of association, ISA, to determine the randomness of the distribution of alleles (Haubold and Hudson, 2000). This statistic is expected to be zero in populations that are freely recombining and greater than zero if there is linkage disequilibrium. ISA was estimated to be 0.086 when all 106 isolates were analyzed and this value was significantly different from zero (P < 0.001). However, when ISA is calculated using only the 49 unique STs the value decreases to 0.028 (P = 0.028). Similar values were obtained when the analysis was restricted to the strains isolated in 2006 (Table 8). The ISA statistic was also calculated for the set of isolates from each spring separately and the ISA values were higher when the calculation was restricted to the subpopulations (Table 8).

As stated above, there were 11 SLVs pairs among the T. uzonensis genotypes. Following the method of binning recombination and mutation events (Feil et al., 2000), SLVs are considered to be the result of mutation if they are single nucleotide changes and are unique in the dataset, whereas recombination events can have single or multiple nucleotide changes and are encountered several times independently. Of the 11 SLVs, seven appear to be due to recombination events while four are due to mutation (Table 7).

Discussion

The study of variability in natural populations is important because it can provide insight into the evolutionary forces through which variation develops and is maintained (Smith, 1995). The diversity of 106 T. uzonensis strains, isolated from seven hot springs within one region, was assessed through the sequencing and analysis of eight protein coding loci. This MLSA revealed that while recombination occurs, the subpopulations from different springs in this region are genetically differentiated. The results presented here are based on an initial culture-dependent step where the focus was to obtain similar strains under identical isolation conditions. As such, we acknowledge that this set of T. uzonensis strains may not necessarily reflect the full diversity of T. uzonensis in this environment.

A 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity of ≥97% between strains is evidence that the isolates may belong within the same species (Stackebrandt and Goebel, 1994). Therefore the high (≥98%) 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity to each other and to Thermoanaerobacter uzonensis strain JW/IW010T (Wagner et al., 2008) supported the view that these isolates belong to the same species. This idea was further bolstered by the MLSA results, in particular the relatively low amount of nucleotide sequence variation at the protein coding loci.

The eight protein coding loci examined within the T. uzonensis population were polymorphic and a range of variation was observed across the different loci (Table 3). Comparable levels of sequence diversity have been observed in other MLSA-based studies of the population structure of a microbial species within a region. The number of polymorphic sites per locus varied from 2 to 12 for six protein-coding loci from 60 Sulfolobus isolates from the Mutnovsky region of Kamchatka, Far East Russia (Whitaker et al., 2005), and among 36 Halorubrum isolates from two solar salterns at Santa Pola near Alicante, Spain, four protein-coding loci had 30–61 polymorphic sites per locus (Papke et al., 2004).

The spatial scale of microbial diversity studies are important to consider. Previous authors have noted that environmental factors or historical contingencies are thought to influence patterns of genetic variation on smaller scales, while isolation distance is believed to supersede environmental effects at intercontinental scales (Takacs-Vesbach et al., 2008). For example, greater divergence among the protein-coding loci was reported for both Sulfolobus (Whitaker et al., 2003) and Halorubrum (Papke et al., 2007) when the isolates analyzed were from regions separated by ≥250 km. While the focus of this report is the diversity of T. uzonensis within Uzon Caldera hot springs, similar strains were also isolated from two hot springs within the Geyser Valley region, 10 km east of the Uzon Caldera, and one hot spring from the Mutnovsky volcano region, located 250 km south of the Uzon Caldera and Geyser Valley. Analyses with the protein-coding loci from these strains revealed, with few exceptions, an increase in genetic divergence with an increase in geographic distance (data not shown).

The genetic diversity values, H, calculated for the gyrB, recA and rplB loci were relatively low (Table 3), and for these three genes a particular allele was found held by a high percentage of the T. uzonensis strains. A similar observation was made for a set of Halorubrum isolates where the a single bop allele was found in >85% of the strains and this was interpreted as being in part the result of selection, which drove the allele to high frequency (Papke, 2009). This explanation is compatible with some of the genes examined within the T. uzonensis population. The most notable exceptions were the pyrG and recG loci. Balancing selection may, in part, explain the diverse set of recG alleles observed within the population. Interestingly, for the pyrG locus a particular allele was often only found among the strains from a single hot spring (Figure 2). This could be the result of genetic drift within subpopulations, a neutral force, or positive selection of the particular allele within the hot spring subpopulation. One potential observation from a MLSA study would be the clustering of genotypes according to origin in a phylogenetic tree prepared from concatenates of the different loci. Only limited clustering was sequence types was observed (Figure 3), but this was not an unexpected result. The genes included in this study may have been influenced by different evolutionary processes, which potentially complicates phylogenetic analyses, and moreover there was evidence for homologous recombination in this population.

The investigated hot springs were separated by distances of 140–1600 m (Figure 1), and therefore T. uzonensis strains that developed in one pool could be distributed among the springs of the Uzon Caldera by wind, water, and local fauna (e.g., birds and brown bears). Moreover, there was evidence that gene flow between regions occurs as the same rplB allele was found in isolates from the Uzon Caldera, Geyser Valley, and Mutnovsky volcano regions (data not shown). Many of the described Thermoanaerobacter taxa, including T. uzonensis JW/IW010T, are known to form spores or contain sporulation-specific genes (Brill and Wiegel, 1997; Onyenwoke et al., 2004; Wagner et al., 2008). Sporulation would undoubtedly contribute to the ability of T. uzonensis to survive transport between geothermal springs within and between regions, a form of passive dispersal as discussed by Martiny et al. (2006). Despite the close spatial proximity of the hot springs in this study, the pairwise FST values indicated that there was a small but significant level of genetic differentiation between most subpopulations (Table 4). There was a negligible association between the genetic divergence of T. uzonensis isolates and the geographic separation of the corresponding hot springs. This observation supports the concept mentioned earlier: that on smaller scales, as mainly investigated in this study, environmental factors or historical contingencies are believed to be of primary importance in determining whether patterns of genetic variation exist (Takacs-Vesbach et al., 2008).

Although the different geothermal springs sampled had approximately the same temperature and pH where the sample was collected (Table 1), there were other physicochemical differences. For example, the Arkashin Shaft spring is geochemically distinct in that it has a high arsenic concentration (4252 mg kg−1 measured within Arkashin Shaft in 2006; Burgess et al., 2011). The hot springs in this study also differed in size and physical setting. Previous studies have revealed that at the community level microbial richness increases with habitat volume (Bell et al., 2005; Van Der Gast et al., 2005). The Burlyashi spring was the largest hot spring sampled (personal observation) and this property may, in part, explain the high diversity observed among the 18 strains from the Burlyashi spring outflow (Table 5).

Analyses of microbial populations have revealed that while homologous recombination occurs at widely varying rates, it has been observed among most taxa (Papke et al., 2007). The genomes of Thermoanaerobacter strains isolated from the Piceance Basin, Colorado, USA, revealed considerable recombination (C. L. Hemme, unpublished results). Our results show that the T. uzonensis population in the Uzon Caldera was influenced by frequent recombination. However, the difference in ISA values calculated from all 106 isolates and the 49 unique STs (Table 8) provides evidence of an “epidemic” population structure, in which recombination occurs while particular clones also rise in frequency. Sulfolobus isolates from two hot springs in the Mutnovsky region of Kamchatka, similarly had an epidemic population structure (Whitaker et al., 2005), and this population structure has been proposed as indicating that certain clonal types may have increased fitness. Within the T. uzonensis population the view that a sequence type held by multiple isolates has increased fitness is particularly intriguing considering the sequence types found over consecutive years within the Arkashin and Thermophilny springs.

While there is great potential for T. uzonensis strains to be transferred between hot springs within the Uzon Caldera, isolates with identical sequence types were always derived from the same spring and SLV sequence types were usually isolated from a single site. This observation, along with the pairwise FST values, suggests that the T. uzonensis subpopulations within different hot springs are ecologically distinct and future studies could be performed to further examine the genetic and physiological differences between strains. Moreover, the genetic differentiation of subpopulations is likely influenced by the physicochemical differences between the geothermal springs. While there was strong evidence for frequent recombination within the T. uzonensis population, the observation that subpopulations were genetically differentiated is not unexpected. Simulations performed by Hanage et al. (2006) demonstrated that distinct clusters of similar genotypes can emerge in populations with a range of mutation and recombination rates. This MLSA additionally suggests that there are interesting genome dynamics within the T. uzonensis taxon with some alleles approaching fixation throughout the entire population. Other alleles were only seen within particular subpopulations, potentially the result of positive selection within the hot spring or genetic drift. Comparing the genomes of strains from different springs would provide insight into the genomic context of the protein-coding loci herein examined and would provide information concerning the variation in gene content among strains. While physical isolation of subpopulations is an important factor that influences the genetic divergence between sites, this work shows that differentiated populations can emerge within a region.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NSF grants MCB 0238407 (Kamchatka Microbial Observatory). We thank D. E. Crowe, P. A. Schroeder, C. S. Romanek, C. L. Zhang, E. A. Burgess, E. A. Bonch-Osmolovskaya, and the other members of the Kamchatka Microbial Observatory for assistance in the field. We thank E. Yokoyama, and A. Torrens for their preliminary work with the sequencing of protein coding gene loci.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://www.frontiersin.org/Frontiers_in_Extreme_Microbiology/10.3389/fmicb.2013.00169/abstract

References

Achtman, M., and Wagner, M. (2008). Microbial diversity and the genetic nature of microbial species. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6, 431–440.

Bell, T., Ager, D., Song, J.-I., Newman, J. A., Thompson, I. P., Lilley, A. K., et al. (2005). Larger islands house more bacterial taxa. Science 308, 1884. doi: 10.1126/science.1111318

Bonch-Osmolovskaya, E., Miroshnichenko, M., Chernykh, N., Kostrikina, N., Pikuta, E., and Rainey, E. (1997). Reduction of elemental sulfur by moderately thermophilic organotrophic bacteria and the description of Thermoanaerobacter sulfurophilus sp. nov. Mikrobiologiya 66, 581–587.

Brill, J. A., and Wiegel, J. (1997). Differentiation between spore-forming and asporogenic bacteria using a PCR and Southern hybridization based method. J. Microbiol. Methods 31, 29–36. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7012(97)00091-2

Burgess, E. A., Unrine, J. M., Mills, G. L., Romanek, C. S., and Wiegel, J. (2011). Comparative geochemical and microbiological characterization of two thermal pools in the Uzon Caldera, Kamchatka, Russia. Microb. Ecol. 63, 471–489. doi: 10.1007/s00248-011-9979-4

Cooper, J. E., and Feil, E. J. (2004). Multilocus sequence typing– what is resolved? Trends Microbiol. 12, 373–377. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.06.003

Desantis, T. Z., Hugenholtz, P., Larsen, N., Rojas, M., Brodie, E. L., Keller, K., et al. (2006). Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 5069–5072. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03006-05

Excoffier, L., and Lischer, H. E. L. (2010). Arlequin suite ver 3.5: a new series of programs to perform population genetics analyses under Linux and Windows. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 10, 564–567. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2010.02847.x

Feil, E. J., Smith, J. M., Enright, M. C., and Spratt, B. G. (2000). Estimating recombinational parameters in Streptococcus pneumoniae from multilocus sequence typing data. Genetics 154, 1439–1450.

Gevers, D., Cohan, F. M., Lawrence, J. G., Spratt, B. G., Coenye, T., Feil, E. J., et al. (2005). Re-evaluating prokaryotic species. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3, 733–739. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1236

Hanage, W. P., Spratt, B. G., Turner, K. M. E., and Fraser, C. (2006). Modelling bacterial speciation. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 361, 2039–2044. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1926

Haubold, B., and Hudson, R. R. (2000). LIAN 3.0: detecting linkage disequilibrium in multilocus data. Bioinformatics 16, 847–849. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.9.847

Hemme, C. L., Mouttaki, H., Lee, Y.-J., Zhang, G., Goodwin, L., Lucas, S., et al. (2010). Sequencing of multiple clostridial genomes related to biomass conversion and biofuel production. J. Bacteriol. 192, 6494–6496. doi: 10.1128/JB.01064-10

Hreggvidsson, G. O., Skirnisdottir, S., Smit, B., Hjorleifsdottir, S., Marteinsson, V. T., Petursdottir, S., et al. (2006). Polyphasic analysis of Thermus isolates from geothermal areas in Iceland. Extremophiles 10, 563–575. doi: 10.1007/s00792-006-0530-3

Karpov, G. A., and Naboko, S. I. (1990). Metal contents of recent thermal waters, mineral precipitates and hydrothermal alteration in active geothermal fields, Kamchatka. J. Geochem. Explor. 36, 57–71. doi: 10.1016/0375-6742(90)90051-B

Lane, D. J. (1991). “16S/23S rRNA sequencing,” in Nucleic Acid Techniques in Bacterial Systematics, eds E. Stackebrandt and M. Goodfellow (Chichester: Wiley), 115–175.

Larkin, M. A., Blackshields, G., Brown, N. P., Chenna, R., Mcgettigan, P. A., Mcwilliam, H., et al. (2007). Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23, 2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404

Martiny, J. B. H., Bohannan, B. J. M., Brown, J. H., Colwell, R. K., Fuhrman, J. A., Green, J. L., et al. (2006). Microbial biogeography: putting microorganisms on the map. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4, 102–112. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1341

Miller, S. R., Castenholz, R. W., and Pedersen, D. (2007). Phylogeography of the thermophilic cyanobacterium Mastigocladus laminosus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 4751–4759. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02945-06

Onyenwoke, R. U., Brill, J. A., Farahi, K., and Wiegel, J. (2004). Sporulation genes in members of the low G+ C Gram-type-positive phylogenetic branch (Firmicutes). Arch. Microbiol. 182, 182–192. doi: 10.1007/s00203-004-0696-y

Papke, R. T. (2009). A critique of prokaryotic species concepts. Methods Mol. Biol. 532, 379–395. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-853-9_22

Papke, R. T., Koenig, J. E., Rodríguez-Valera, F., and Doolittle, W. F. (2004). Frequent recombination in a saltern population of Halorubrum. Science 306, 1928–1929.

Papke, R. T., Ramsing, N. B., Bateson, M. M., and Ward, D. M. (2003). Geographical isolation in hot spring cyanobacteria. Environ. Microbiol. 5, 650–659. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2003.00460.x

Papke, R. T., Zhaxybayeva, O., Feil, E. J., Sommerfeld, K., Muise, D., and Doolittle, W. F. (2007). Searching for species in haloarchaea. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 14092–14097. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706358104

Petursdottir, S. K., Hreggvidsson, G. O., Da Costa, M. S., and Kristjansson, J. K. (2000). Genetic diversity analysis of Rhodothermus reflects geographical origin of the isolates. Extremophiles 4, 267–274. doi: 10.1007/s007920070012

Rozas, J., and Rozas, R. (1999). DnaSP version 3: an integrated program for molecular population genetics and molecular evolution analysis. Bioinformatics 15, 174–175. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/15.2.174

Santos, S. R., and Ochman, H. (2004). Identification and phylogenetic sorting of bacterial lineages with universally conserved genes and proteins. Environ. Microbiol. 6, 754–759. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2004.00617.x

Slobodkin, A. I., Tourova, T. P., Kuznetsov, B. B., Kostrikina, N. A., Chernyh, N. A., and Bonch-Osmolovskaya, E. A. (1999). Thermoanaerobacter siderophilus sp. nov., a novel dissimilatory Fe (III)-reducing, anaerobic, thermophilic bacterium. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 49, 1471–1478. doi: 10.1099/00207713-49-4-1471

Smith, J. M. (1995). “Do bacteria have population genetics,” in SGM Symposium 52: Population Genetics of Bacteria, eds S. Baumberg, J. P. W. Young, E. M. H. Wellington, and J. R. Saunders (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press), 1–12.

Stackebrandt, E., and Goebel, B. M. (1994). Taxonomic note: a place for DNA-DNA reassociation and 16S rRNA sequence analysis in the present species definition in bacteriology. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 44, 846–849. doi: 10.1099/00207713-44-4-846

Takacs-Vesbach, C., Mitchell, K., Jackson-Weaver, O., and Reysenbach, A. L. (2008). Volcanic calderas delineate biogeographic provinces among Yellowstone thermophiles. Environ. Microbiol. 10, 1681–1689. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01584.x

Tamura, K., Dudley, J., Nei, M., and Kumar, S. (2007). MEGA4: molecular genetic evolutionary analysis (MEGA) software. Version 4.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 1596–1599. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092

Tamura, K., Peterson, D., Peterson, N., Stecher, G., Nei, M., and Kumar, S. (2011). MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121

Van Der Gast, C. J., Lilley, A. K., Ager, D., and Thompson, I. P. (2005). Island size and bacterial diversity in an archipelago of engineering machines. Environ. Microbiol. 7, 1220–1226. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00802.x

Wagner, I. D., Zhao, W., Zhang, C. L., Romanek, C. S., Rohde, M., and Wiegel, J. (2008). Thermoanaerobacter uzonensis sp. nov., an anaerobic thermophilic bacterium isolated from a hot spring within the Uzon Caldera, Kamchatka, Far East Russia. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 58, 2565–2573. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.65343-0

Whitaker, R. J. (2006). Allopatric origins of microbial species. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 361, 1975–1984 doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1927

Whitaker, R. J., Grogan, D. W., and Taylor, J. W. (2003). Geographic barriers isolate endemic populations of hyperthermophilic archaea. Science 301, 976–978. doi: 10.1126/science.1086909

Keywords: multilocus sequence analysis, Thermoanaerobacter, microbial biogeography, Uzon Caldera, Kamchatka, hot springs

Citation: Wagner ID, Varghese LB, Hemme CL and Wiegel J (2013) Multilocus sequence analysis of Thermoanaerobacter isolates reveals recombining, but differentiated, populations from geothermal springs of the Uzon Caldera, Kamchatka, Russia. Front. Microbiol. 4:169. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00169

Received: 24 January 2013; Accepted: 04 June 2013;

Published online: 21 June 2013.

Edited by:

Andreas Teske, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, USAReviewed by:

Patricia L. Siering, Humboldt State University, USAAntonio Ventosa, University of Sevilla, Spain

Copyright © 2013 Wagner, Varghese, Hemme and Wiegel. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in other forums, provided the original authors and source are credited and subject to any copyright notices concerning any third-party graphics etc.

*Correspondence: Juergen Wiegel, Department of Microbiology, University of Georgia, 1000 Cedar Street, Athens, GA 30602-2605, USA e-mail: juergenwiegel@gmail.com

†Present address: Isaac D. Wagner, Denver, USA e-mail: isaacwagner56@gmail.com