- 1Fujian Key Laboratory of Marine Enzyme Engineering, Fuzhou University, Fuzhou, China

- 2Faculty of Medicine, School of Biomedical Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China

Laccases can oxidize a wide range of aromatic compounds and are industrially valuable. Laccases often exist in gene families and may differ from each other in expression and function. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was used for transcription profiling of eight laccase genes in Cerrena sp. strain HYB07 with validated reference genes. A high laccase activity of 280.0 U/mL was obtained after submerged fermentation for 5 days. Laccase production and laccase gene transcription at different fermentation stages and in response to various environmental cues were revealed. HYB07 laccase activity correlated with transcription levels of its predominantly expressed laccase gene, Lac7. Cu2+ ions were indispensable for efficient laccase production by HYB07, mainly through Lac7 transcription induction, and no aromatic compounds were needed. HYB07 laccase synthesis and biomass accumulation were highest with non-limiting carbon and nitrogen. Glycerol and inorganic nitrogen sources adversely impacted Lac7 transcription, laccase yields, and fungal growth. The present study would further our understanding of transcription regulation of laccase genes, which may in turn facilitate laccase production as well as elucidation of their physiological roles.

Introduction

White-rot fungi secrete ligninolytic enzymes such as lignin peroxidases, manganese peroxidases, versatile peroxidases, and laccases (Wong, 2009). Laccases comprise a class of multi-copper containing oxidases that are environmentally friendly and industrially important. Laccases have low substrate specificity and can oxidize a wide range of substrates such as phenolic lignin compounds, recalcitrant dyestuffs, and other environment pollutants, accompanied by concomitant reduction of molecular oxygen to water. Laccases have found applications in food, bioremediation, textile, biofuel, and other industries (Giardina et al., 2010).

Unraveling gene expression patterns is important for elucidating gene function as well as metabolic engineering to improve yields of desired products. Northern blotting, semi-quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), and quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) have been used to determine mRNA abundance. Laccase production, often at the level of transcription, responds to various environmental signals such as metal ions, aromatic compounds, and carbon and nitrogen sources and concentrations (Piscitelli et al., 2011; Janusz et al., 2013). The changes in laccase gene expression levels are also likely related to their function during the fungal life cycle (Solé et al., 2012). However, only a few laccase expression studies used qPCR, and most of them focused on one or a few laccase genes. Fungal laccases usually exist in gene families, and the family members have different biochemical properties and responses to inducers and nutrients (Giardina et al., 2010).

qPCR is a powerful tool in expression quantification and has gained popularity because it is fast, sensitive, accurate, and cost-effective. Recently, transcription of the laccase gene family in Pleurotus ostreatus has been profiled (Castanera et al., 2012, 2013; Pezzella et al., 2012). On the other hand, when it comes to other white-rot fungi, few comprehensive qPCR analyses on the laccase gene families are available, even though the induction response can be gene- and strain-specific (Piscitelli et al., 2011; Janusz et al., 2013). Furthermore, many existing qPCR reports use housekeeping gene(s) for data normalization without prior validation, which can lead to erroneous interpretation of the results (Kozera and Rapacz, 2013).

The genus Cerrena has recently attracted research attention with its potentials in laccase production and applications (D'souza et al., 2006; Michniewicz et al., 2006; Elisashvili et al., 2010; Lisova et al., 2010; Kucharzyk et al., 2012; Songulashvili et al., 2012). Despite sequencing of C. unicolor genome (http://www.jgi.doe.gov), expression regulation of Cerrena laccase genes remains largely unknown. We have isolated a white-rot fungus Cerrena sp. strain HYB07 with high laccase yields in a short production cycle. Two HYB07 laccases (i.e., Lac1 and 7) have been characterized; they have different pH and temperature optima, substrate ranges and catalytic activity (Yang et al., 2014, 2015). In the present study, transcription of eight laccase genes in Cerrena sp. HYB07 at different phases of submerged fermentation and in response to various inducers (metal ions and aromatic compounds), carbon/nitrogen ratios and carbon and nitrogen sources was investigated. The present work will provide a theoretical foundation for elucidating the complex molecular mechanism underlying laccase expression regulation in Cerrena sp. HYB07 and pave the way for its commercialization and utilization.

Materials and Methods

Strain, Culturing Conditions, and Sample Preparation

Cerrena sp. strain HYB07 (Yang et al., 2014) was maintained on potato dextrose agar (PDA) (Difco, USA) at 4°C in the culture collection of Fuzhou University, China. For laccase fermentation, 5 mycelial plugs (1 cm diameter) were removed from the peripheral region of 4-days-old PDA plate stored at 30°C and inoculated in 50 mL potato dextrose broth (PDB) seed medium in a 250 mL Erlenmeyer flask. After growing for 2 days at 30°C and 200 rpm, an aliquot was transferred to a second PDB medium at the ratio of 8% (v/v). After another 2 days, the fermentation medium (50 mL in 250 mL Erlenmeyer flasks) was inoculated with the second seed culture at the concentration of 8% (v/v). Unless otherwise stated, the fermentation medium contained (g L−1): maltodextrin, 60; peptone, 10; ammonium tartrate, 1.6; KH2PO4, 6; MgSO4·7H2O, 4.14; CaCl2, 0.3; NaCl, 0.18; CuSO4·5H2O, 0.0625; ZnSO4·7H2O, 0.018; and vitamin B1 0.015. This medium was also referred to as the control, regular or HNHC (high nitrogen and high carbon) medium in this manuscript.

To test the effects of inducers on laccase production, Cu2+ or Zn2+ ions were not added to the fermentation medium; aromatic compounds, including 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS), caffeic acid, ferulic acid, guaiacol, p-hydroxybenzoic acid, nicotinic acid, syringic acid, and vanillic acid, were individually added at a final concentration of 0.5 mM. ABTS was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (USA), and all other aromatic compounds were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd (China) or Aladdin (China). For media with different carbon/nitrogen ratios, HNLC (high nitrogen and low carbon) medium contained 6 g dextrin instead of 60 g; LNHC (low nitrogen and high carbon) contained 1 g peptone and 0.16 g ammonium tartrate instead of 10 and 1.6 g, respectively; LNLC (low nitrogen and low carbon) medium contained 6 g dextrin, 1 g peptone, and 0.16 g ammonium tartrate. For media with different carbon sources, dextrin was replaced with glucose (monosaccharide), fructose (monosaccharide), maltose (disaccharide), sucrose (disaccharide), or glycerol at the same concentration of 6%. For media with alternative nitrogen sources, peptone was substituted with 10 g NH4NO3 or ammonium tartrate, while 1.6 g ammonium tartrate in the original medium recipe remained the same. Since our preliminary experiments showed that addition of aromatic compounds on day 0 (the time of culture inoculation) impaired fungal growth, aromatic compounds were added on day 2; all other treatments started from day 0. Laccase activity was measured on day 6. For each treatment, two independent experiments were carried out with three replicates for each experiment.

Subsequently, selected samples were analyzed with qPCR. For growth phase experiments, mycelia were harvested every 24 h from days 1 to 6. For ABTS and guaiacol treatments, control and treated fungal cultures were taken on the fourth day of fermentation. For all other treatments, the control and treated cultures were collected on the second day, when biomass reached maximum and extracellular laccase activity was on exponential increase. These other treatments included: media with no additional Cu2+ or Zn2+, various carbon/nitrogen ratios (HNLC, LNHC, and LNLC) and alternative carbon and nitrogen sources (i.e., glucose, sucrose, glycerol, NH4NO3 and ammonium tartrate).

Enzyme Activity Assay and Fungal Dry Mass Determination

Extracellular laccase activity was spectrophotometrically assayed at 30°C and pH 3.0 with ABTS at 420 nm. One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme needed to oxidize 1 μmol ABTS in 1 min. All measurements were carried out in triplicate.

For biomass measurements, triplicate cultures were harvested at the same time as for qPCR analysis. Mycelia were filtered with pre-dried Whatman filter paper, dried in an oven at 70°C for 24 h and weighed.

RNA Extraction and Reverse Transcription

Mycelia from three biological replicates were pooled, and total RNA was extracted with Trizol (Life Technologies, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA quantity was measured with a NanoDrop 2000 UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, USA). The ratios of the absorbance at 260 and 280 nm of the samples were between 1.8 and 2.0. RNA integrity was checked by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis before reverse transcription (data not shown).

Contaminating genomic DNA was removed and reverse transcription was carried out by using TransScript One-Step gDNA Removal and cDNA Synthesis SuperMix (Transgen, China). Each reaction contained 2 μg total RNA, 0.5 μg oligo-(dT)12−18 primer and 1 μM 18S-rRNA-specific primer (the reverse qPCR primer for 18S rRNA) (Zhu and Altmann, 2005; Yang et al., in press).

Primers

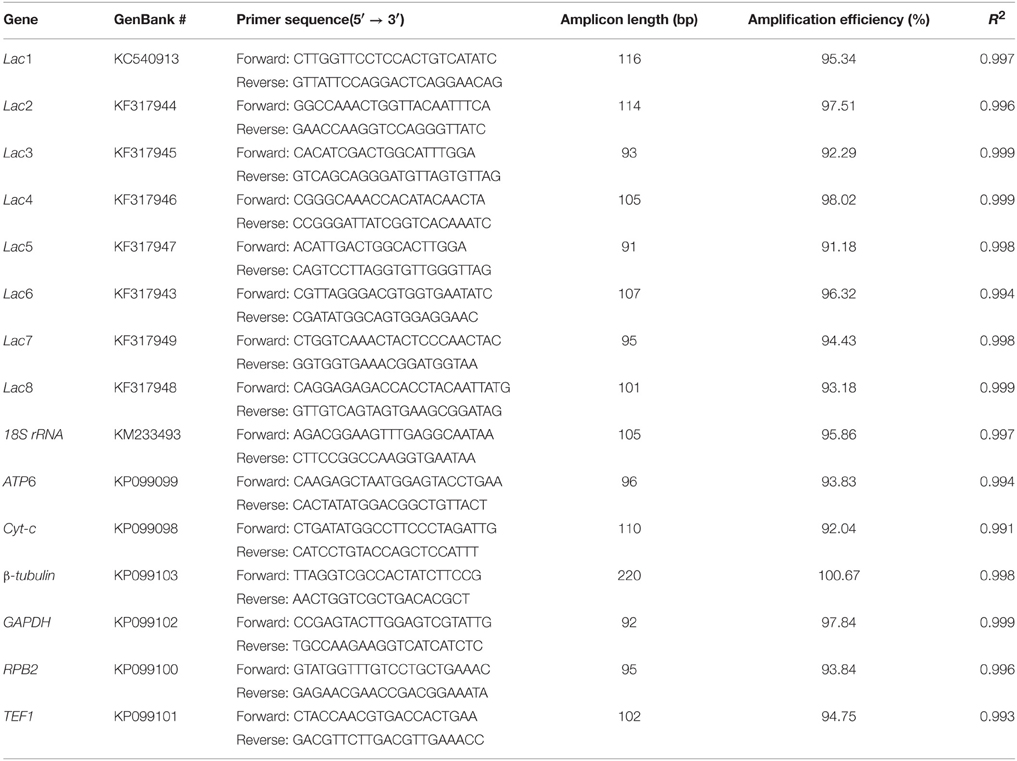

qPCR primers for the eight laccase genes (Lac1-8) and housekeeping genes were designed by PrimerQuest (Integrated DNA Technologies, USA; Table 1). All qPCR primer pairs were specific, as determined by agarose gel electrophoresis (data not shown) and melting curves (Supplementary Figure S1) of qPCR products. Amplification efficiencies of the primer pairs were calculated from the standard curves of serial 1:10 dilutions of DNA templates (cDNA or recombinant plasmids containing the target gene fragments). The amplification efficiencies were 91.2–100.7% (R2 ≥ 0.99), and the amplicon sizes ranged from 91–220 bp.

Table 1. qPCR primers for the eight laccase genes and seven housekeeping genes in Cerrena sp. HYB07.

qPCR

qPCR was performed on an Applied BioSystems 7500 Real-Time PCR system (Life Technologies, USA). Each reaction mixture (20 μL) contained 10 μL 2 × TransStart Top Green qPCR SuperMix (Transgen, China), 0.4 μL 50 × Passive Reference DyeII, forward and reverse primers (each at 200 nM), and 2 μL cDNA (1:50 diluted). Amplification was carried out as follows: an initial denaturation step of 94°C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of 94°C for 5 s and 60°C for 34 s. All reactions were performed in triplicate. RT negative controls (containing RNA template without reverse transcription) were run for every sample by using 18S rRNA as the target to check for DNA presence. No-template negative controls were included every run to detect possible contamination or carryover.

The 2−▵▵Ct relative quantification strategy (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001; Schmittgen and Livak, 2008) was employed to calculate relative quantities of the laccase transcripts under various experimental conditions by using the ExpressionSuite v1.0.3 (Life Technologies, USA). Validated reference genes were used for data normalization.

Reference Gene Selection

Expression stability of seven candidate reference genes, including 18S rRNA, ATP6 (ATP synthase 6), β-tubulin, Cyt-c (cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1), GAPDH (glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase), RPB2 (RNA polymerase II second largest subunit), and TEF1 (translation elongation factor 1-alpha), under various experimental conditions were evaluated with geNorm (Vandesompele et al., 2002). geNorm defines the stability index M as the average pairwise variation of a particular gene with all other candidate genes, and M-values below 1.5 indicate high expression stability. Stability ranking is achieved through stepwise exclusion of the most variable gene, and the M-values for the remaining genes are recalculated. The two most stable genes cannot be ranked in order since gene ratios are used to measure gene stability. geNorm also determines minimum number (n) of reference genes based on pairwise variation (Vn/n+1) analysis between the normalization factors NFn and NFn+1. The recommended cutoff value (0.15) was adopted, so the minimal number of reference genes was decided from the first Vn/n+1 value lower than 0.15.

Samples were divided into five groups for reference gene selection. Group A consisted of six samples collected on days 1 to 6; Group B consisted of six samples under different induction conditions (no Cu2+, no Zn2+, ABTS, guaiacol, and the respective controls); Group C consisted of four samples cultivated under different carbon/nitrogen ratios (HNHC, HNLC, LNHC, and LNLC); Group D consisted of six samples cultivated under different carbon or nitrogen sources (glucose, sucrose, glycerol, NH4NO3, ammonium tartrate, and control); Group E contained all the samples. Groups C and D shared the same 2nd-day control sample fermented in the regular medium, which was also a control for Group B in addition to a 4th-day control (for aromatic compound treatment). Samples were grouped for laccase gene transcription analysis based on selected reference genes.

Results

Laccase Production by Cerrena sp.

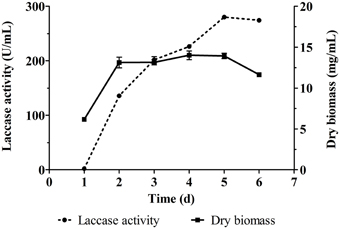

Cerrena sp. HYB07 is a white-rot fungal strain with high laccase yields and a short production cycle (Yang et al., 2014). The fermentation medium used in this study resulted in higher laccase yields (280.0 U/mL) than previously used PDY medium (210.8 U/mL). The strain showed a linear increase in biomass during the first 2 days and then entered stationary phase of growth (Figure 1). Laccase production of Cerrena sp. HYB07 in response to various metal ions, aromatic compounds, carbon/nitrogen ratios and nutrients was investigated.

Figure 1. Laccase production and biomass accumulation of Cerrena sp. HYB07. Fermentation was carried out in 250 mL Erlenmeyer flasks at 30°C and 200 rpm. The fermentation medium (50 mL) was inoculated with the second seed culture at the concentration of 8% (v/v). The fermentation medium contained (g L−1): maltodextrin, 60; peptone, 10; ammonium tartrate, 1.6; KH2PO4, 6; MgSO4·7H2O, 4.14; CaCl2, 0.3; NaCl, 0.18; CuSO4·5H2O, 0.0625; ZnSO4·7H2O, 0.018; and vitamin B1 0.015.

Effects of Metal Ions on Laccase Production

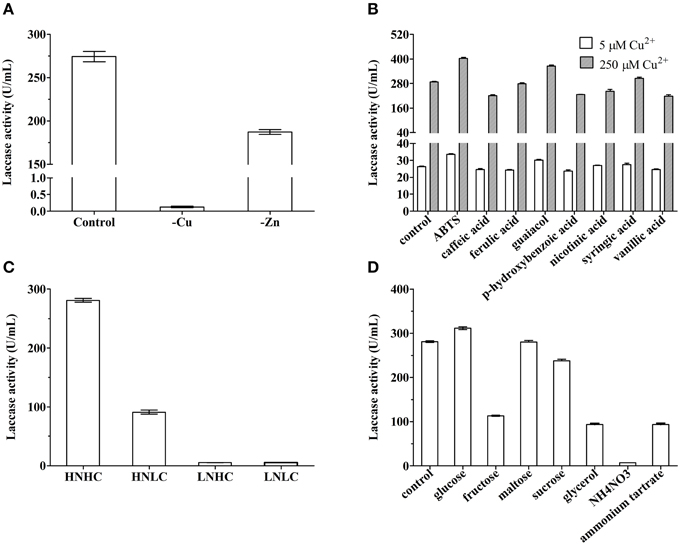

Our preliminary work showed that MnSO4, CoCl2, FeSO4, AlK(SO4)2, NaMoO4, and H3BO3 did not influence or negatively influenced laccase production, whereas Cu2+ and Zn2+ stimulated laccase production. Indeed, when Cu2+ or Zn2+ ions were not added to the fermentation medium, extracellular laccase activity was lowered by 99.95 and 31.78%, respectively (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Laccase production of Cerrena sp. HYB07 in response to metal ions (A), aromatic compounds (B), carbon/nitrogen ratios (C), and nutrient types (D). To test the effects of inducers on laccase production, Cu2+ or Zn2+ ions were not added to the fermentation medium; aromatic compound ABTS, caffeic acid, ferulic acid, guaiacol, p-hydroxybenzoic acid, nicotinic acid, syringic acid, or vanillic acid, was added at a final concentration of 0.5 mM. For media with different carbon/nitrogen ratios, quantities of carbon and nitrogen sources were alternatively or simultaneously reduced to 10% of the levels in the control medium. For media with different nutrient sources, dextrin was replaced with glucose, fructose, maltose, sucrose or glycerol, and peptone was substituted with 10 g NH4NO3 or ammonium tartrate. Aromatic compounds were added on day 2 of fermentation, whereas all other treatments started from day 0. Extracellular laccase activity was measured on day 6.

Effects of Aromatic Compounds on Laccase Production

Previous work showed that 0.5 mM veratryl alcohol, tannic acid, xylene, phenol, or vanillin failed to improve HYB07 laccase production with 250 μM Cu2+. Effects of eight aromatic compounds were tested at two copper concentrations (250 μM as used in the medium and a low copper concentration of 5 μM) (Figure 2B). The highest induction responses were observed with ABTS and guaiacol, which increased laccase production by 40.1 and 26.7% at 250 μM Cu2+ and by 28.0 and 15.1% at 5 μM Cu2+, respectively. The other aromatic compounds either did not affect or negatively affected laccase production. Overall, laccase yields in the presence of various aromatic compounds were similar regardless of the Cu2+ concentration, although the response at the low Cu2+ concentration of 5 μM was lower than the response at 250 μM Cu2+ concentration.

Effects of Carbon/Nitrogen Ratios on Laccase Production

Concentrations and types of carbon and nitrogen nutrients also affected laccase production by Cerrena sp. HYB07 (Figures 2C,D). High carbon and nitrogen concentrations in the fermentation medium were beneficial for laccase production (280.0 U/mL), whereas low nitrogen concentrations, regardless of the carbon concentration, dramatically reduced laccase yields to approximately 5.3 U/mL. A laccase activity of 91.0 U/mL, approximately one-third of that of the control medium, was obtained with the HNLC medium (Figure 2C).

Effects of Carbon and Nitrogen Sources on Laccase Production

Glucose slightly increased laccase yield to 311.4 U/mL, whereas fructose decreased laccase production by 60% to 113.6 U/mL. Disaccharide maltose did not affect laccase yields, and sucrose lowered laccase yields by 15.5%. Among all carbon sources tested, the lowest laccase activity (93.7 U/mL) was observed with glycerol (Figure 2D). Ammonium nitrate and ammonium tartrate instead of peptone led to laccase production of only 7.1 and 94.8 U/mL, respectively (Figure 2D).

To better understand the mechanism underlying laccase synthesis, qPCR was used to explore the effects of growth phases, inducers, carbon/nitrogen ratios, as well as carbon and nitrogen sources on laccase gene transcription. Based on laccase production studies, the following parameters were selected: (1) days 1–6 of fermentation; (2) no supplementary Cu2+ or Zn2+; (3) presence of ABTS or guaiacol; (4) alternative carbon source glucose, sucrose or glycerol; (5) alternative nitrogen source NH4NO3 or ammonium tartrate.

Reference Gene Selection

For accurate interpretation of qPCR results, expression stability of seven housekeeping genes, namely 18S rRNA, ATP6, Cyt-c, GAPDH, RPB2, TEF1, and β-tubulin was analyzed with geNorm (Vandesompele et al., 2002). No versatile reference genes were identified for all samples since all Vn/n+1 values of Group E were higher than 0.15 (Supplementary Figure S2). Therefore, the reference genes were selected based on experimental variables: a combination of four references genes (i.e., Cyt-c, ATP6, TEF1, and β-tubulin) for different growth phases (Group A); GAPDH and Cyt-c for different induction conditions (Group B); ATP6 and TEF1 for various carbon/nitrogen ratios (Group C); and GAPDH and Cyt-c for various carbon or nitrogen sources (Group D) (Supplementary Figure S2). Next, laccase transcription was analyzed with the respective reference genes.

Transcription Profiling of Cerrena sp. Laccase Genes

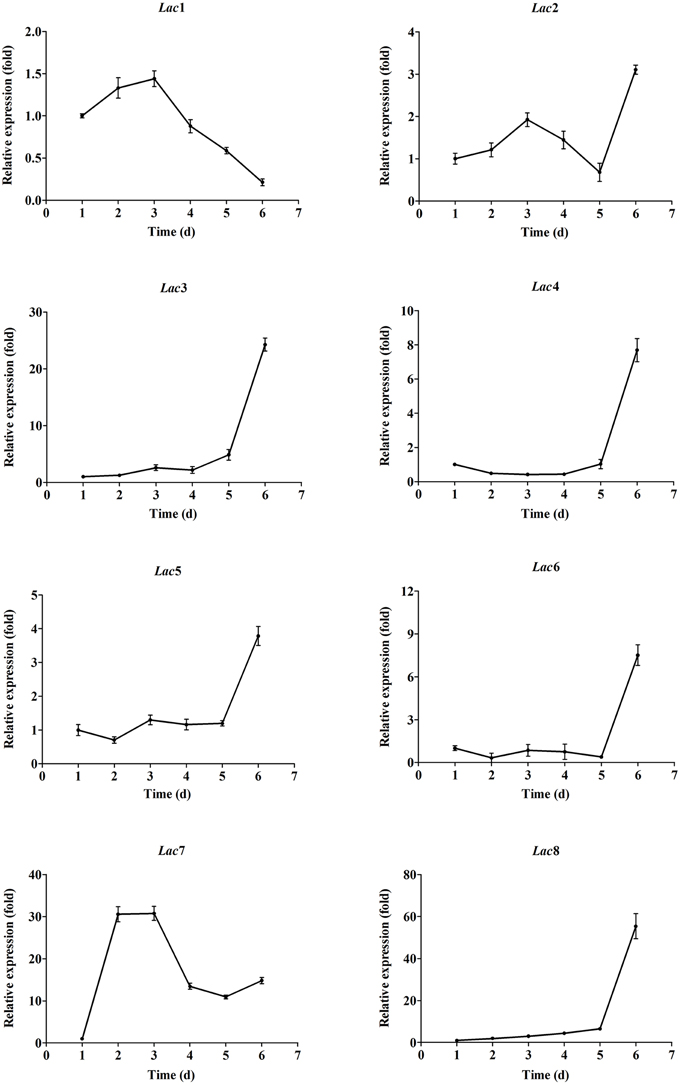

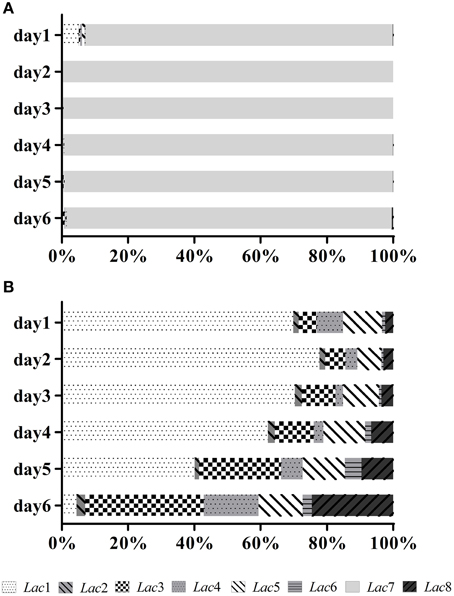

Transcription profiles of the eight laccase genes during submerged fermentation are shown in Figure 3. Most significant changes (>10-fold) in transcription levels were observed with Lac3, 7, and 8. Transcription of Lac3, 4, 5, 6, and 8 was up-regulated as cells aged; the expression levels on day 6 was 24.3-, 7.7-, 3.8-, 7.5-, and 55.4-fold of the corresponding expression levels on day 1. In contrast, Lac1 and 7 transcription peaked on days 2-3 and decreased to 0.2- and 14.8-fold on day 6 compared to that on day 1. Lac2 transcript levels fluctuated throughout the fermentation period. Among the eight laccase genes, Lac7 was predominantly expressed, accounting for 93–99% of all transcripts of the eight laccase genes (Figure 4A). Lac1 was the second most abundantly expressed except for day 6, when Lac3 was the second most abundantly expressed (Figure 4B), but the expression levels of Lac1 or 3 were negligible relative to those of Lac7.

Figure 3. Expression of the eight laccase genes in Cerrena sp. HYB07 during submerged fermentation in a 250-mL Erlenmeyer flask. Transcript levels of each gene on different days are expressed as fold changes compared to the transcript level on day 1. The reference genes used for normalization were Cyt-c, ATP6, TEF1, and β-tubulin.

Figure 4. Relative transcript abundance (expressed as a percentage) of the laccase genes during fermentation. (A) Relative transcript abundance of the eight laccase genes. The total transcript level of all laccase genes was taken as 100%. (B) Relative transcript abundance of the seven laccase genes after excluding the predominantly-expressed Lac7. The total transcript level of the seven laccase genes was taken as 100%.

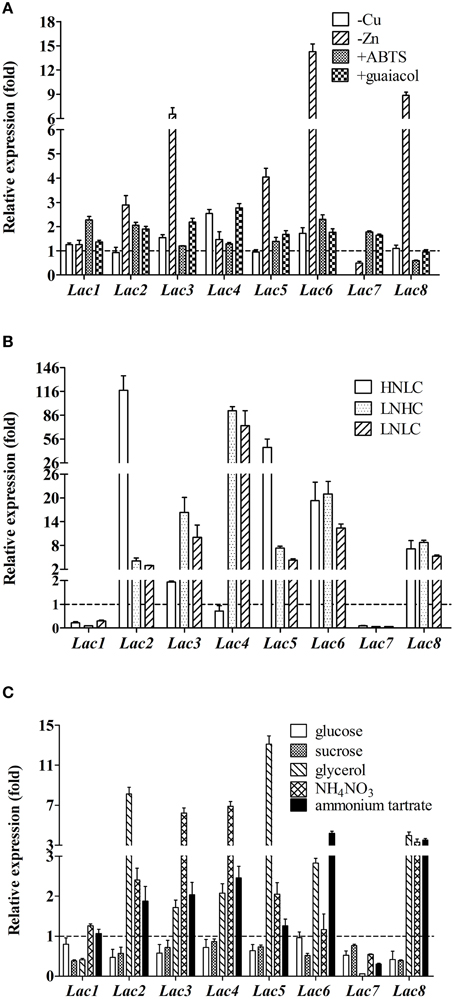

When copper ions were not supplemented in the fermentation medium, Lac7 transcript level was diminished by 1000-fold. Opposite to Lac7, Lac4 transcription level was higher (2.5-fold) in the absence of Cu2+ ions (Figure 5A). Lac7 was also induced by Zn2+ ions, although to a less extent compared to induction by Cu2+ ions; its transcript level was reduced by approximately 50% without Zn2+ ions. Expression of Lac2, 3, 5, 6, and 8 was suppressed by Zn2+ ions, with Lac6 being the most remarkably suppressed (Figure 5A).

Figure 5. Relative expression of the eight laccase genes in Cerrena sp. HYB07 in response to metal ions (A), aromatic compounds (A), carbon/nitrogen ratios (B), and nutrient types (C). Transcript levels of each gene in treated samples are expressed as fold changes compared to the transcript level in the control sample (fermented in the control medium) harvested and analyzed at the same time. Treated samples were collected on the second day of fermentation except for aromatic compound-treated samples, which were collected on day 4 (aromatic compounds were added to the fermentation media on day 2). The reference genes used for normalization were as follows: (A) GAPDH and Cyt-c for different induction conditions; (B) ATP6 and TEF1 for various carbon/nitrogen ratios; (C) GAPDH and Cyt-c for various carbon or nitrogen sources.

ABTS and guaiacol also affected laccase gene transcription (Figure 5A). Approximately two-fold relative expression levels were observed with Lac1, 2, and 6 upon ABTS addition. In the presence of guaiacol, Lac3 and 4 transcription was up-regulated by 2.2- and 2.8-fold. Changes in the expression levels of other laccase genes were less than two-fold.

More dramatic differences were seen with various carbon/nitrogen ratios (Figure 5B). Lac2 was significantly up-regulated in the HNLC medium by 117.5-fold, followed by Lac5 (45.6-fold), Lac6 (19.3-fold), and Lac8 (7.1-fold). In the two low nitrogen media, similar responses were observed, regardless of the carbon concentration. Lac4 was most remarkably up-regulated by limiting nitrogen, followed by Lac6, 3, 8, 5, and 2. Low carbon or nitrogen concentrations inhibited expression of Lac7 (by 11.0- to 16.7-fold) and Lac1 (by 10.1- to 3.2-fold).

Glucose and sucrose slightly down-regulated transcription of most laccase genes (Figure 5C). Glycerol induced expression of Lac2, 4, 5, 6, and 8 by 13.1- to 2.1-fold. On the other hand, glycerol suppressed Lac7 expression by 17.9-fold; Lac1 expression was also reduced, albeit to a lesser degree (2.4-fold).

Five laccase genes, namely Lac2, 3, 4, 5, and 8, responded to the inorganic nitrogen source NH4NO3 with enhanced expression (with Lac3 and 4 exhibiting highest fold changes of >6). Ammonium tartrate up-regulated transcription of Lac3, 4, 6, and 8. Lac7 mRNA levels were low with both inorganic nitrogen sources (Figure 5C).

Putative cis-Acting Responsive Elements in Laccase Gene Promoters

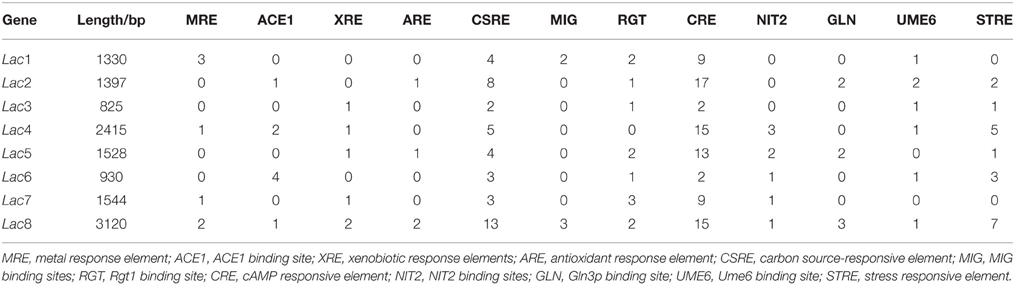

Genomatix (http://www.genomatix.de/cgi-bin/eldorado/main.pl) identified multiple putative cis-acting transcription regulation sites within the promoter of the eight laccase genes in both orientations, in (Table 2). Promoters of Lac1, 4, 7, and 8 had predicted metal response elements (MREs). Lac6 promoter contained the highest number (4) of ACE1 copper-responsive transcription factor binding sites, followed by 2 in Lac4 promoter and 1 in Lac2 and 8 promoters. Promoters of Lac3 and 5 did not contain any MRE or ACE1 sites. Xenobiotic response elements (XREs) were found in five promoters except for Lac1, 2, and 6 promoters.

Carbon- and nitrogen-responsive elements were also identified. All promoters contained various numbers (2–13) of potential carbon source-responsive elements (CSREs; Roth and Schüller, 2001), whereas putative MIG-binding sites were only found in Lac1 and 8 promoters; zinc finger transcription factor MIG is involved in glucose repression (Lundin et al., 1994). In addition, repressor Rgt1-binding sites were present in the promoters of all laccase except for Lac4; Rgt1 binding to DNA is inhibited by glucose (Kim et al., 2003). There were also numerous cAMP-responsive elements in the laccase promoters with possible roles in catabolite-related signaling. Ume6 regulates gene transcription responding to metabolites such as glucose and nitrogen (Williams et al., 2002), and putative Ume6 recognition sites were located in all promoters except for those of Lac5 and 7. NIT2 binding sites were identified in five laccase promoters but not those of Lac1-3, and NIT2 activates gene expression during nitrogen limitation (Fu and Marzluf, 1990). Furthermore, GATA family transcription factor Gln3p binding sites were predicted in Lac2, 5, and 8 promoters and might regulate responses of these genes to nitrogen (Coffman et al., 1997). Different types and numbers of putative regulatory elements in the promoter regions suggested differential transcription regulation of these laccase genes.

Discussion

Cerrena sp. HYB07 has been recently reported as a laccase-producing strain with commercial values due to its high laccase yields and short production cycle. Its main laccase, Lac7 (originally named as LacA), has high specific activity, wide substrate specificity and strong decolorization ability (Yang et al., 2014). Laccase production of Cerrena sp. HYB07 was regulated by fermentation stages, metal ions, aromatic compounds, carbon/nitrogen ratios, and nutrient types. In order to account for the influence of biomass accumulation on total laccase production, dry biomass-based laccase activity was calculated (Supplementary Figure S3). Although mRNA abundance does not directly translate to protein abundance, dry mass-based laccase activity largely agreed with Lac7 transcript levels (Supplementary Figures S4, S5), and fluctuations in Lac7 transcription levels constituted a major cause of fluctuations in laccase yields.

Cu2+ ion is the most widely used inducer in laccase production, and it was crucial for high laccase yields of Cerrena sp. HYB07. The steep increase in laccase activity upon Cu2+ addition was supported by a 1000-fold induction of Lac7 transcription by Cu2+ ions. Other factors may also contribute to high laccase activity in the presence of Cu2+ ions. For example, Cu2+ ions are needed at the laccase active site (Solé et al., 2012) and may decrease extracellular proteolytic activity (Piscitelli et al., 2011). Of the HYB07 laccase family, Lac7 was the only gene inducible by Cu2+ ions. Zinc ions can substitute copper in transcription activation of certain genes (Collins and Dobson, 1997); Lac7 mRNA abundance and HYB07 laccase production were increased by Zn2+ ions by approximately two-fold, less dramatic than the up-regulation by Cu2+ ions.

Aromatic compounds are routinely added to fungal cultures to induce laccase production (Giardina et al., 2010; Piscitelli et al., 2011). For example, syringic acid, among others, enhanced laccase levels of Trametes velutina 5930, and the stimulatory effect was synergic with Cu2+ ions. In fact, little enzyme activity was detected in cultures not supplemented with any aromatic compound (Yang et al., 2013). Surprisingly, most aromatic compounds tested did not increase HYB07 laccase production regardless of the copper concentration; ABTS and guaiacol only mildly stimulated laccase synthesis. Lack of yield improvements by aromatic compounds was also observed with HYB07 in PDY medium with or without Cu2+ supplementation (Supplementary Figure S6). Therefore, laccase synthesis by HYB07 was efficient in the absence of aromatic compounds, which would be beneficial for its commercial production. Similarly, C. unicolor VKMF-3196 laccase production needed Cu2+ ions, but not aromatic compounds, and an activity of 15 U/mL was achieved after 8-days fermentation (Lisova et al., 2010).

The HNHC medium was most suitable for HYB07 growth and laccase production. Laccase production and biomass accumulation were compromised more severely in the two LN media than in HNLC, implying the importance of sufficient nitrogen in fungal growth and production. Limiting carbon and/or nitrogen reduced Lac7 transcription level by over 90%, leading to dramatic decreases in laccase activity. Note that up-regulation of other laccase genes might partially compensate for the decreases in Lac7 transcript levels. Furthermore, different laccase compositions were expected at various carbon/nitrogen ratios except for the two LN conditions with similar laccase transcription patterns (Supplementary Figure S4C). Variations in laccase composition have also been demonstrated in Coprinus comatus, which produced six laccase isozymes in the HNLC culture and only two in HNHC, LNHC, and LNLC cultures. In C. comatus, however, laccase activity was highest in LNHC medium (Jiang et al., 2013).

Nitrogen source plays a key role in fungal growth and laccase production. It is commonly believed that inorganic nitrogen sources lead to low laccase yields despite sufficient biomass, whereas organic nitrogen sources render high laccase yields (Piscitelli et al., 2011). Indeed, organic nitrogen source peptone favored laccase production and biomass accumulation of HYB07. In contrast, HYB07 fermentation in NH4NO3 resulted in little biomass and laccase production, as in LN media. Expression profiles of the eight laccase genes with NH4NO3 also resembled those in LNHC and LNLC samples. We speculated that NH4NO3 was an inefficient nitrogen source for HYB07, creating a low-nitrogen-like environment. On the other hand, ammonium tartrate allowed for decent fungal growth in spite of low laccase production. It also induced expression of laccase genes responsive to limiting nitrogen, such as Lac3, 4, 6, and 8, and suppressed Lac7 transcription.

Carbon sources and concentrations have divergent effects on laccase production, depending on the fungal strain (Piscitelli et al., 2011). Glucose repression of laccase expression has been reported for basidiomycete I-62 (Mansur et al., 1998) and Trametes sp. AH28-2 (Xiao et al., 2006). In this study, glucose and sucrose (60 g/L) resulted in lower laccase gene transcription levels on day 2, although laccase activity on day 6 was higher in glucose medium. Glycerol was probably not a preferred carbon source for HYB07 and created a low-carbon-like environment, reducing fungal growth and laccase secretion. Laccase genes also behaved similarly with glycerol as with HNLC: Lac7 and 1 transcription levels were down-regulated, accompanied by significant promotion of Lac2 and 5 expression. In both cases, Lac5 transcripts became the second most abundant (Supplementary Figures S4D, 5D).

Putative transcription regulatory elements in the promoter regions of the laccase genes suggested that their expression was regulated. For instance, global transcription regulation of the laccase gene family by carbon and nitrogen was consistent with the presence of various responsive elements implicated in carbon and nitrogen response/repression. Lac4 expression was responsive to limiting nitrogen, which could be accounted for by three putative NIT2 sites in its promoter (the highest number of the eight laccase promoters). Lac2 transcription was greatly induced under low carbon conditions; of its eight predicted CSREs, three were adjacent (within the region of -456 to -417 upstream of ATG); this was reminiscent of the distribution pattern of three CSREs in the promoter of MDH2 (malate dehydrogenase gene 2) required for gluconeogenic growth of Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Roth and Schüller, 2001). However, there was not a definite causal relationship between the prediction of an element and the presumed response, or between the number of an element and the intensity of the expected response. For example, Lac7 was strongly induced by Cu2+ ions, but no putative ACE1 copper-responsive transcription factor binding site was identified in its promoter despite the presence of one MRE. It was likely that Lac7 contained a non-conventional copper-responsive element or that the induction was through a mechanism not involving ACE1 or MREs, as previously proposed (Collins and Dobson, 1997). Lac4 and 6 contained 2 and 4 potential ACE1 binding sites, respectively, and their expression was either suppressed by Cu2+ ions or changed less than two-fold in response to Cu2+ ions. Prediction of the responsive elements based on consensus sequences had its limitations and was no doubt an oversimplification of the complex network controlling transcription of laccase genes. Moreover, complex and differential laccase gene transcription patterns were probably the results of a combination of parameters. For example, as the cells age, oxidative stress is accumulated (Si and Cui, 2013), accompanied by depletion of carbon and nitrogen nutrients. Laccase expression could also be regulated by factors including cAMP (Crowe and Olsson, 2001), heat shock (Wang et al., 2012), and calmodulin (Suetomi et al., 2015).

We selected the appropriate reference genes for laccase gene transcription profiling. Housekeeping genes are commonly used as normalization references in relative quantification qPCR experiments, although they may show expression variability with different experimental factors (Kozera and Rapacz, 2013; Castanera et al., 2015). For example, GAPDH is one of the most widely used reference genes, but it was unstable with various carbon/nitrogen sources in this study. Therefore, it was necessary to select stable reference genes for accurate data interpretation. Although, it would be ideal to use the same reference genes for all experimental conditions, we could not find such versatile reference genes and therefore divided samples based on experimental variables for reference gene selection and data analysis. This strategy of evaluating candidate reference genes for grouped as well as combined samples is commonly used. Whether versatile reference genes could be identified depended on the organism, candidate genes, and experimental conditions (Zhao et al., 2011; Kianianmomeni and Hallmann, 2013; Kozera and Rapacz, 2013; van Rijn et al., 2014). In order to further illustrate the importance of choosing stable reference genes, we compared laccase gene expression data under HNLC conditions normalized with two choices of reference genes: (1) ATP6 and TEF1 (as selected by geNorm), and (2) GAPDH. Contradicting or overestimation of the expression values were obtained by the two normalization strategies (Supplementary Figure S7), reinforcing the need to validate reference genes before each gene expression analysis.

Conclusions

The present study provided insights into laccase production by Cerrena sp. HYB07. Cu2+ ions, carbon/nitrogen ratios and certain nutrient types exerted remarkable influence on its laccase yields. Lac7 was the main laccase gene under expression throughout the fermentation cycle, and its transcript abundance was correlated with laccase yields under various experimental conditions. Lac7 transcription was up-regulated by copper and zinc ions and down-regulated by scarcity of nitrogen and carbon. The advantages of Cerrena sp. HYB07 for industrial production were manifested. Efficient laccase synthesis by HYB07 did not require toxic xenobiotic compounds. Furthermore, high expression levels of Lac7 under high carbon and high nitrogen conditions allow for accumulation of fungal biomass for laccase production. More research is needed to experimentally validate functionality of the putative cis-acting regulatory elements in the laccase promoters and decipher the complex regulatory network underlying laccase expression. Future work can also be directed to engineer the strong Lac7 promoter to drive expression of other, including laccase, genes.

Author Contributions

JY, JL, and XY designed the research, JY and GW performed the experiments, JY and TN analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript, JL and XY contributed reagents.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a grant from the Natural Science Foundation of China (41306120) and Oceanic Public Welfare Industry Special Research Project of China (201305015).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2015.01558

References

Castanera, R., López-Varas, L., Pisabarro, A. G., and Ramírez, L. (2015). Validation of reference genes for transcriptional analyses in Pleurotus ostreatus by using reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81, 4120–4129. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00402-15

Castanera, R., Omarini, A., Santoyo, F., Pérez, G., Pisabarro, A. G., and Ramírez, L. (2013). Non-additive transcriptional profiles underlie dikaryotic superiority in Pleurotus ostreatus laccase activity. PLoS ONE 8:e73282. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073282

Castanera, R., Péreza, G., Omarini, A., Alfaro, M., Pisabarro, A. G., Faraco, V., et al. (2012). Transcriptional and enzymatic profiling of Pleurotus ostreatus laccase genes in submerged and solid-state fermentation cultures. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 4037–4045. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07880-11

Coffman, J. A., Rai, R., Loprete, D. M., Cunningham, T., Svetlov, V., and Cooper, T. G. (1997). Cross regulation of four GATA factors that control nitrogen catabolic gene expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Bacteriol. 179, 3416–3429.

Collins, P. J., and Dobson, A. D. W. (1997). Regulation of laccase gene transcription in Trametes versicolor. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63, 3444–3450.

Crowe, J. D., and Olsson, S. (2001). Induction of laccase activity in Rhizoctonia solani by antagonistic Pseudomonas fluorescens strains and a range of chemical treatments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67, 2088–2094. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.5.2088-2094.2001

D'Souza, D. T., Tiwari, R., Sah, A. K., and Raghukumar, C. (2006). Enhanced production of laccase by a marine fungus during treatment of colored effluents and synthetic dyes. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 38, 504–511. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2005.07.005

Elisashvili, V., Kachlishvili, E., Khardziani, T., and Agathos, S. N. (2010). Effect of aromatic compounds on the production of laccase and manganese peroxidase by white-rot basidiomycetes. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 37, 1091–1096. doi: 10.1007/s10295-010-0757-y

Fu, Y. H., and Marzluf, G. A. (1990). nit-2, the major positive-acting nitrogen regulatory gene of Neurospora crassa, encodes a sequence-specific DNA-binding protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 87, 5331–5335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.14.5331

Giardina, P., Faraco, V., Pezzella, C., Piscitelli, A., Vanhulle, S., and Sannia, G. (2010). Laccases: a never-ending story. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 67, 369–385. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0169-1

Janusz, G., Kucharzyk, K. H., Pawlik, A., Staszczak, M., and Paszczynski, A. J. (2013). Fungal laccase, manganese peroxidase and lignin peroxidase: gene expression and regulation. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 52, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2012.10.003

Jiang, M., Ten, Z., and Ding, S. (2013). Decolorization of synthetic dyes by crude and purified laccases from Coprinus comatus grown under different cultures: the role of major isoenzyme in dyes decolorization. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 169, 660–672. doi: 10.1007/s12010-012-0031-z

Kianianmomeni, A., and Hallmann, A. (2013). Validation of reference genes for quantitative gene expression studies in Volvox carteri using real-time RT-PCR. Mol. Biol. Rep. 40, 6691–6699. doi: 10.1007/s11033-013-2784-z

Kim, J.-H., Polish, J., and Johnston, M. (2003). Specificity and regulation of DNA binding by the yeast glucose transporter gene repressor Rgt1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 5208–5216. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.15.5208-5216.2003

Kozera, B., and Rapacz, M. (2013). Reference genes in real-time PCR. J. Appl. Genet. 54, 391–406. doi: 10.1007/s13353-013-0173-x

Kucharzyk, K. H., Janusz, G., Karczmarczyk, I., and Rogalski, J. (2012). Chemical modifications of laccase from white-rot basidiomycete Cerrena unicolor. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 168, 1989–2003. doi: 10.1007/s12010-012-9912-4

Lisova, Z. A., Lisov, A. V., and Leontievsky, A. A. (2010). Two laccase isoforms of the basidiomycete Cerrena unicolor VKMF-3196. Induction isolation and properties. J. Basic Microbiol. 50, 72–82. doi: 10.1002/jobm.200900382

Livak, K. J., and Schmittgen, T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods 25, 402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262

Lundin, M., Nehlin, J. O., and Ronne, H. (1994). Importance of a flanking AT-rich region in target site recognition by the GC box-binding zinc finger protein MIG1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14, 1979–1985. doi: 10.1128/MCB.14.3.1979

Mansur, M., Suárez, T., and González, A. E. (1998). Differential gene expression in the laccase gene family from basidiomycete I-62 (CECT 20197). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64, 771–774.

Michniewicz, A., Ullrich, R., Ledakowicz, S., and Hofrichter, M. (2006). The white-rot fungus Cerrena unicolor strain 137 produces two laccase isoforms with different physico-chemical and catalytic properties. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 69, 682–688. doi: 10.1007/s00253-005-0015-9

Pezzella, C., Lettera, V., Piscitelli, A., Giardina, P., and Sannia, G. (2012). Transcriptional analysis of Pleurotus ostreatus laccase genes. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 97, 705–717. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-3980-9

Piscitelli, A., Giardina, P., Lettera, V., Pezzella, C., Sannia, G., and Faraco, V. (2011). Induction and transcriptional regulation of laccases in fungi. Curr. Genomics 12, 104–112. doi: 10.2174/138920211795564331

Roth, S., and Schüller, H.-J. (2001). Cat8 and Sip4 mediate regulated transcriptional activation of the yeast malate dehydrogenase gene MDH2 by three carbon source-responsive promoter elements. Yeast 18, 151–162. doi: 10.1002/1097-0061(20010130)18:2<151::AID-YEA662>3.0.CO;2-Q

Schmittgen, T. D., and Livak, K. J. (2008). Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nat. Protoc. 3, 1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73

Si, J., and Cui, B.-K. (2013). Study of the physiological characteristics of the medicinal mushroom Trametes pubescens (higher basidiomycetes) during the laccase-producing process. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 15, 199–210. doi: 10.1615/IntJMedMushr.v15.i2.90

Solé, M., Müller, I., Pecyna, M. J., Fetzer, I., Harms, H., and Schlosser, D. (2012). Differential regulation by organic compounds and heavy metals of multiple laccase genes in the aquatic hyphomycete Clavariopsis aquatica. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 4732–4739. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00635-12

Songulashvili, G., Jimenéz-Tobón, G. A., Jaspers, C., and Penninckx, M. J. (2012). Immobilized laccase of Cerrena unicolor for elimination of endocrine disruptor micropollutants. Fungal Biol. 116, 883–889. doi: 10.1016/j.funbio.2012.05.005

Suetomi, T., Sakamoto, T., Tokunaga, Y., Kameyama, T., Honda, Y., Kamitsuji, H., et al. (2015). Effects of calmodulin on expression of lignin-modifying enzymes in Pleurotus ostreatus. Curr. Genet. 61, 127–140. doi: 10.1007/s00294-014-0460-z

van Rijn, S., Riemers, F., van den Heuvel, D., Wolfswinkel, J., Hofland, L., Meij, B., et al. (2014). Expression stability of reference genes for quantitative RT-PCR of healthy and diseased pituitary tissue samples varies between humans, mice, and dogs. Mol. Neurobiol. 49, 893–899. doi: 10.1007/s12035-013-8567-7

Vandesompele, J., Preter, K. D., Pattyn, F., Poppe, B., Roy, N. V., Paepe, A. D., et al. (2002). Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 3:research0034.1–0034.11. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-research0034

Wang, F., Guo, C., Wei, T., Zhang, T., and Liu, C.-Z. (2012). Heat shock treatment improves Trametes versicolor laccase production. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 168, 256–265. doi: 10.1007/s12010-012-9769-6

Williams, R. M., Primig, M., Washburn, B. K., Winzeler, E. A., Bellis, M., Menthière, C. S., et al. (2002). The Ume6 regulon coordinates metabolic and meiotic gene expression in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 13431–13436. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202495299

Wong, D. W. (2009). Structure and action mechanism of ligninolytic enzymes. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 157, 174–209. doi: 10.1007/s12010-008-8279-z

Xiao, Y. Z., Hong, Y. Z., Li, J. F., Hang, J., Tong, P. G., Fang, W., et al. (2006). Cloning of novel laccase isozyme genes from Trametes sp. AH28-2 and analyses of their differential expression. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 71, 493–501. doi: 10.1007/s00253-005-0188-2

Yang, J., Lin, Q., Lin, J., and Ye, X. (in press). Selection validation of reference genes for quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction studies in Cerrena unicolor (higher basidiomyetes). Int. J. Med. Mushrooms.

Yang, J., Lin, Q., Ng, T. B., Ye, X., and Lin, J. (2014). Purification and characterization of a novel laccase from Cerrena sp. HYB07 with dye decolorizing ability. PLoS ONE 9:e110834. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110834

Yang, J., Ng, T. B., Lin, J., and Ye, X. (2015). A novel laccase from basidiomycete Cerrena sp.: cloning, heterologous expression, and characterization. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 77, 344–349. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.03.028

Yang, Y., Wei, F., Zhuo, R., Fan, F., Liu, H., Zhang, C., et al. (2013). Enhancing the laccase production and laccase gene expression in the white-rot fungus Trametes velutina 5930 with great potential for biotechnological applications by different metal ions and aromatic compounds. PLoS ONE 8:e79307. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079307

Zhao, W., Li, Y., Gao, P., Sun, Z., Sun, T., and Zhang, H. (2011). Validation of reference genes for real-time quantitative PCR studies in gene expression levels of Lactobacillus casei Zhang. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 38, 1279–1286. doi: 10.1007/s10295-010-0906-3

Keywords: Cerrena sp., qPCR, laccase, differential regulation, promoter

Citation: Yang J, Wang G, Ng TB, Lin J and Ye X (2016) Laccase Production and Differential Transcription of Laccase Genes in Cerrena sp. in Response to Metal Ions, Aromatic Compounds, and Nutrients. Front. Microbiol. 6:1558. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01558

Received: 23 October 2015; Accepted: 22 December 2015;

Published: 12 January 2016.

Edited by:

Weiwen Zhang, Tianjin University, ChinaCopyright © 2016 Yang, Wang, Ng, Lin and Ye. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Juan Lin, ljuan@fzu.edu.cn;

Xiuyun Ye, xiuyunye@fzu.edu.cn

Jie Yang

Jie Yang Guozeng Wang

Guozeng Wang Tzi Bun Ng

Tzi Bun Ng Juan Lin1*

Juan Lin1*