- 1Department of Microbiology, Panjab University, Chandigarh, India

- 2Department of Biotechnology, Panjab University, Chandigarh, India

Acinetobacter baumannii is emerging as a serious nosocomial pathogen with multidrug resistance that has made it difficult to cure and development of efficacious treatment against this pathogen is direly needed. This has led to investigate vaccine approach to prevent and treat A. baumannii infections. In this work, an outer membrane putative pilus assembly protein, FilF, was predicted as vaccine candidate by in silico analysis of A. baumannii proteome and was found to be conserved among the A. baumannii strains. It was cloned and expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) and purified by Ni-NTA chromatography. Immunization with FilF generated high antibody titer (>64,000) and provided 50% protection against a standardized lethal dose (108 CFU) of A. baumannii in murine pneumonia model. FilF immunization reduced the bacterial load in lungs by 2 and 4 log cycles, 12 and 24 h post infection as compared to adjuvant control; reduced the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-6, IL-33, IFN-γ, and IL-1β significantly and histology of lung tissue supported the data by showing considerably reduced damage and infiltration of neutrophils in lungs. These results demonstrate the in vivo validation of immunoprotective efficacy of a protein predicted as a vaccine candidate by in silico proteomic analysis and open the possibilities for exploration of a large array of uncharacterized proteins.

Introduction

A. baumannii has, over the last decade, emerged as a threatening cause of bacteremia, pneumonia, septicemia, urinary tract infections, wound sepsis, endocarditis and meningitis in hospitalized patients. In certain parts of the world, it is a serious cause of community-acquired infections (Peleg et al., 2008). Although previously it was ignored as a “low-grade pathogen” due to its low virulence but its ability to cause disease and its profile of extensive drug resistance is now recognized, making A. baumannii an “untreatable pathogen,” especially among the patients in intensive care units (Joly-Guillou, 2005; Fournier and Richet, 2006).

A. baumannii is resistant to broad-spectrum cephalosporins due to overexpression of the chromosomal AmpC-type cephalosporinase (Corvec et al., 2003; Rodriguez-Martinez et al., 2010). Additionally, there are frequent reports of acquired resistance (Coelho et al., 2004) to all beta-lactams, mainly due to enzymatic degradation by carbapenem hydrolyzing beta-lactamases. Resistance to fluoroquinolones and aminoglycosides is also very common (Coelho et al., 2004; Peleg et al., 2008), facilitating its adaptation to environmental selection pressure and leading to the rapid worldwide emergence of multidrug-resistance. As a last resort, there has been increased use of antibiotics such as colistin (Li et al., 2006; Peleg et al., 2008), unfortunately leading to the emergence of colistin-resistant strains (Adams et al., 2009; Rolain et al., 2011; Qureshi et al., 2015). The extensive drug resistance of this pathogen and the predictable failure of future antibiotic treatment options warrant the development of vaccine against A. baumannii.

Several attempts have provided immunological insights to such treatment options against A. baumannii infections e.g., monoclonal antibodies against the iron regulated outer membrane proteins (IROMPs) were found bactericidal and exhibited opsonizing activities during in vitro studies (Goel and Kapil, 2001). Active and passive immunization with inactivated whole cell (McConnell and Pachón, 2010), outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) (McConnell et al., 2011; Huang et al., 2014) and outer membrane complexes (OMCs) (McConnell et al., 2011) demonstrated protection of mice from bacterial challenges. Sub-unit vaccine candidates such as Bap (Fattahian et al., 2011), rOmpA (Luo et al., 2012), Ata (Bentancor et al., 2011) and nuclease (Garg et al., 2016) have been found to provide protection against pathogenic strains. Recently, Moriel et al. (2013) and Chiang et al. (2015) reported a few vaccine candidate proteins in the outer membrane and secretome, and immunization with OmpK, FK IB and Ompp1 provided partial protection from A. baumannii ATCC 17978. In spite of all these studies, there is no vaccine-based treatment available to prevent A. baumannii infections.

There are numerous proteins that need to be explored for their role in virulence and pathogenesis of A. baumannii and also for their vaccine potential. In this work, in silico analysis of A. baumannii ATCC 19606 proteome predicted FilF, an outer membrane, uncharacterized putative pilus assembly protein, as a potential vaccine candidate. It was found to be conserved though its role in virulence is not yet known. FilF was cloned, purified and analyzed by in vitro and in vivo experiments in a murine pneumonia model for its immunoprotective efficacy.

Materials and Methods

Animals, Ethical Clearance, and Bacterial Strains

Pathogen-free, 6–8 weeks old female Balb/c mice were procured from animal house, Panjab University, Chandigarh, India and housed in clean polypropylene cages and fed a standard antibiotic-free diet (Hindustan Lever Products, Kolkata, India) and water ad libitum. Animal studies were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Panjab University, Chandigarh, India. All experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines of Committee for the Purpose of Control and Supervision of Experiments on Animals (CPCSEA), Government of India. All efforts were made to minimize the suffering of animals.

A. baumannii ATCC 19606 was procured from ATCC and was used to establish murine pneumonia model. E.coli BL21 (DE3) and pET28-a plasmid from Novagen were used for cloning and expression of FilF. The bacterial strains were grown in Luria-broth (LB) containing kanamycin (25 μg/ml), wherever required.

In silico Analysis of A. baumannii ATCC 19606 Proteome

Complete proteome of A. baumannii ATCC 19606 was downloaded from NCBI nucleotide database and analyzed for potential vaccine candidates using the Vaxign online tool (He et al., 2010) by searching (i) localization in outer membrane using PSORTb, (ii) number of trans-membrane helices using HMMTOP, (iii) adhesion probability using SPAAN, (iv) no similarity with human and mouse proteome using OrthoMCL, and (v) ability to bind to MHC molecules using Vaxitop. B cell, MHC I and MHC II binding epitopes were predicted by IEDB tools (www.iedb.org). ProtParam was used to analyze the physico-chemical parameters such as molecular weight, hydropathicity, pI and stability. Phyre2 and GOR IV online tools were used to predict the secondary structure of FilF. Tertiary structure of FilF was generated using I-TASSER online tool based on homology modeling. Procheck (Ramachandran Plot) and verify 3-D were used to validate the quality of generated structure.

Cloning and Purification of FilF

Chromosomal DNA of A. baumannii ATCC 19606 was isolated (Sambrook and Russell, 2001) and used as template for PCR. Primers were designed by online tool “OligoEvaluator™” for filF (Accession ID- EEX03804.1, the 6th ORF in fil operon, Supplementary Table S3) having BamHI and XhoI restriction sites in forward (5′- ATAGGATCCTGTGGTGGAGGAAGTT-3′) and reverse primer (5′- TCACTCGAGTTATTTTGTCTTAATTTGATAACAAT-3), respectively. PCR reaction was performed with initial denaturation at 94°C for 3 min followed by 33 thermal cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 1 min, annealing at 55°C for 45 s, and extension at 72°C for 2 min. Final extension was carried out at 72°C for 5 min. The BamHI and XhoI digested PCR product was ligated to similarly digested pET-28a and transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3) by electroporation. Transformants were selected on LB-kanamycin agar plates and confirmed by PCR.

Five hundred milliliter of LB-kanamycin was inoculated with 2.5 ml of overnight grown culture of E. coli BL21 (DE3) containing pET-28a-filF. Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactoside (IPTG) (0.5 mM) was added when OD600 reached 0.8 and induced for 5 h at 37°C/150 rpm. The cells were pelleted and suspended in 50 ml lysis buffer (100 mM phosphate buffer, 300 mM NaCl, 0.2% Tween 20, pH 8) containing 1 mg/ml lysozyme. The cell suspension was sonicated, centrifuged and pellet was solubilized in 100 mM phosphate buffer, pH 8 containing 8 M urea and 300 mM NaCl. The lysate was centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 40 min and supernatant was filtered (0.45 μm) and loaded on Ni-NTA column equilibrated with equilibration buffer (8 M urea, 20 mM Tris–HCl, 100 mM phosphate buffer, pH 8.0). The nonspecific proteins were removed by washing with five column volumes of wash buffer (8 M urea, 20 mM Tris–HCl, 500 mM NaCl, pH 6.9). The bound FilF was eluted with buffer containing 8 M urea, 20 mM Tris–HCl, 500 mM NaCl, 100 mM phosphate buffer, pH 4.5. Eluted fractions were collected and analyzed by 12% SDS PAGE (Laemmli, 2011). The protein was refolded by urea gradient dialysis method according to Qiagen's guidelines. Protein concentration was estimated by Bradford protein estimation kit (Bangalore Genei India Pvt. Ltd.). The endotoxin level of purified recombinant FilF was determined using Limulus Amebocyte Lysate assay kit (Hycult Biotech, The Netherlands) according to manufacturer's guidelines.

A. baumannii Associated Pneumonia Model

A. baumannii associated mouse pneumonia model was established by intratracheal route. Briefly, A. baumannii ATCC 19606 was grown in LB broth to late-logarithmic phase at 37°C/150 rpm. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 6000 × g for 10 min, washed and resuspended in PBS. Different doses of bacteria (106–109 CFU) were obtained by appropriate dilutions and the final cell count was quantified by plating serial dilutions on LB agar plates. Mice were anesthetized with a mixture of xylazine, ketamine and PBS in the ratio 6:1:3, respectively by injecting intraperitoneally. Desired dose of bacteria in a total volume of 50 μl was inoculated directly in trachea by surgery. The incisions were sealed using surgical sutures and betadine was applied on cuts to prevent infections. Group of mice inoculated with PBS served as control. At specific time intervals mice were sacrificed, lungs were isolated aseptically and homogenized for histology and to determine the bacterial counts.

Mouse Immunization and Antibody Titer Measurement by ELISA

FilF specific antibodies were produced in mice according to McConnell et al. (2006). Briefly, the concentration of refolded protein was adjusted to 0.4 mg/ml in sterile PBS and diluted 1:1 (v/v) with Freund's Complete Adjuvant (Sigma). 100 μl of protein-adjuvant mixture was administered in mice sub-cutaneously (20 μg FilF per mouse). Booster doses of protein were given with Freund's Incomplete Adjuvant (Sigma) at 14th and 21st day and sera were collected at day 7, 18, and 25. FilF specific IgG antibodies were measured by ELISA. Briefly, 200 ng FilF in sodium bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.6) was coated to each well by incubation at 4°C overnight. The wells were washed thrice with 0.1% Tween 20 in PBS (PBST) and blocked with 5% BSA in PBST (PBSTM) for 1 h at room temperature. Sera were serially diluted two fold in PBSTM and added to wells followed by incubation for 1 h at 37°C. Wells were washed thrice with PBST and 100 μl of horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-IgG (Bangalore Genei) diluted in PBSM (1:5000) was added to each well and incubated at room temperature for 1 h. Wells were again washed with PBST thrice and 100 μl of horseradish peroxidase substrate (Bangalore Genei India Pvt. Ltd.) was added to each well and developed for 20 min at room temperature. The reaction was stopped with the addition of 100 μl of 2M HCl, and the absorbance was read at 450 nm on an ELISA reader (BioRad). The endpoint titer was defined as the highest dilution at which the optical density at 450 nm was significantly higher than that of control wells receiving control adjuvant serum.

Serum Cytokine's Levels Estimation

Sera were collected from adjuvant control and FilF immunized mice at 12 and 24 h post infection. Serum levels of cytokines TNF-α, IL-6, IL-33, IFN-γ, IL-1β, and IL-10 were estimated using Krishgen Biosystems, India and GenAsia, Philippines kits according to the supplier's instructions. Concentrations were calculated in Graphpad Prism 5 software.

Bacterial Load in Lungs

Mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation and dissected aseptically to remove lungs. The lungs were suspended in 1ml PBS and homogenized. Homogenates were serially diluted and spread plated on Luria agar followed by incubation at 37°C overnight. The number of colony forming units was counted and the results were expressed as log CFU.

Histopathology Examination

Aseptically collected lung specimens were fixed in 10% buffered formalin, stained with hematoxylin-eosin and observed under microscope at 100X magnification.

Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using Graphpad Prism 5 software. The data were presented as mean with standard deviations represented as error bars. One way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied for all the comparisons. Survival rates were analyzed by log-rank test. Results were considered significant at p < 0.05.

Results

Prediction of FilF as Vaccine Candidate using Vaxign

Complete proteome analysis of A. baumannii yielded 57 proteins, predicted as vaccine candidates by Vaxign. An uncharacterized protein FilF was selected for further analysis as it was conserved among the strains of A. baumannii. Physical and chemical parameters of FilF were computed using ProtParam online tool (Supplementary Table S1). FilF is 641 amino acid protein having signal peptide of 20 amino acids which directs its localization to outer membrane. Its predicted molecular weight is ~68kDa with pI 5.21. It possesses high adhesion probability (p = 0.879), no trans-membrane helix and no similarity to human and mouse proteome. Protein-BLAST of FilF showed that it matched and belonged exclusively to Acinetobacter and was present in the sequenced genomes (complete and drafted) of 250 strains of Acinetobacter available in UniProt database. It shared >99% similarity with 25 strains of A. baumannii (Supplementary Table S2), further FilF shared 50–90% in other strains and 35–50% identity in other species of Acinetobacter. Though similarity levels vary but majority of epitopes (B cell, MHC I and MHC II) fall in these identical regions. Upstream and downstream DNA sequences showed that filF is regulated in fil operon and there are 5 other fil genes having different functions (Supplementary Table S3). Secondary structure prediction (Supplementary Figure S1) revealed that FilF is composed of mainly random coils (369 amino acids), extended strands (153 amino acids) and alpha helices (119 amino acids). Homology modeling was done using I-TASSER and 3-D structure was predicted (Supplementary Figure S2). FilF shared no structural similarity in Protein Data Bank (PDB) and I-TASSER used pilus adhesin (RrgA) from Streptococcus pneumoniae as the closest template to generate a 3D structure for FilF but quality of predicted structure was not acceptable as 13 residues out of 641 amino acids of FilF fell into disallowed region of Ramachandran plot (Supplementary Figure S3). B cell, MHC I and MHC II binding epitopes for the HLA alleles prevalent in North India were predicted by IEDB (Supplementary Tables S4–S6, respectively) which supported the strong FilF immunogenicity.

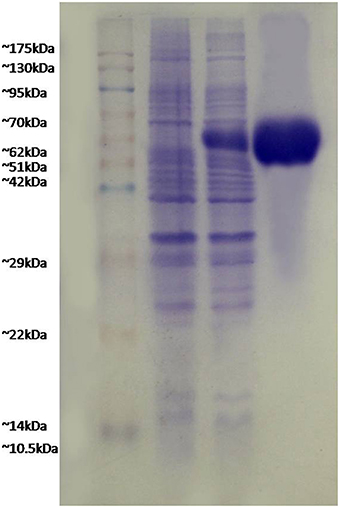

FilF Formed Inclusion Bodies

FilF was cloned in pET-28a (Supplementary Figure S4) and expressed in E.coli BL21 (DE3). Due to over expression, FilF formed inclusion bodies and accumulated in insoluble fraction. Prevention of inclusion bodies was tried by optimizing IPTG concentration (0.01to 1 mM), temperature (15°C to 37°C) and time (1–16 h) but protein still accumulated as inclusion bodies which were dissolved in 8M urea and purified by Ni-NTA chromatography up to a concentration of 40 mg/L. Purified protein was refolded by urea gradient dialysis and resolved on SDS-PAGE (Figure 1). The endotoxin level of purified recombinant protein used for immunization was found to be <1 EU/ml.

Figure 1. Expression and purification of FilF protein. Lane 1, pink plus marker; lane 2, uninduced sample; lane 3, induced FilF; lane 4, purified FilF protein.

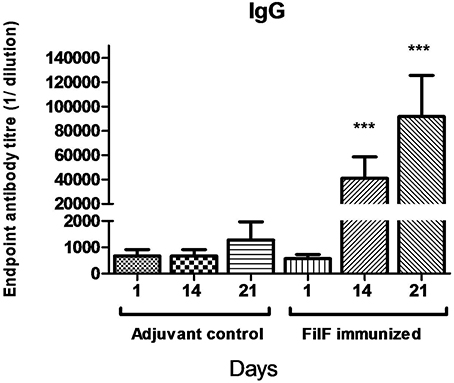

FilF-Specific Antibodies

In order to evaluate the antibody response to immunization with the FilF protein, mice (n = 10) were immunized at day 1, 14, and 21 with 20 μg of purified FilF protein. Significant levels of IgG antibody titer were observed after each booster in the sera of immunized mice as compared to adjuvant control mice (Figure 2). Antibody titer significantly increased to >6.4 × 104 after second booster. The adjuvant control mice did not show any FilF-specific IgG response at any time point.

Figure 2. Total IgG antibody levels in the sera. Groups of female BALB/c mice (n = 10) were sub-cutaneously immunized with 20 μg FilF formulated with CFA/IFA at day 1, 14, and 21. Sera from adjuvant control and FilF immunized mice were collected 3 days after booster dose and IgG titer was determined. Antibody response at 14 and 21-day rose as compared to adjuvant control. ***p < 0.001 (Adjuvant control vs. FilF immunized mice).

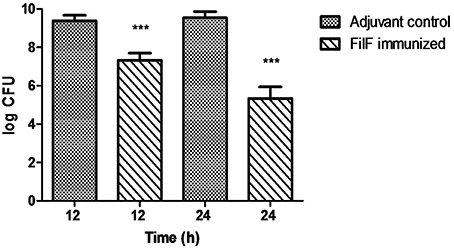

Effect of FilF Immunization on Bacterial Load in Lungs

Different bacterial doses (106–109 CFU) of A. baumannii ATCC 19606 were intratracheally administered to groups of mice and effects were observed. Mice showed mild clinical symptoms postinfection with 106 and 107 CFU of bacteria which were cleared from the body within 2–3 days (data not shown). 108 CFU caused infection resulting in mice death within 24–48 h and this dose was selected for further experiments.

Using the developed murine pneumonia model, the effect of FilF immunization on bacterial load was determined by quantifying bacteria in the lungs of unimmunized and FilF immunized mice 12 and 24 h after infection with 108 CFU of the A. baumannii ATCC 19606. Bacterial load was lowered by only 2 log cycles 12 h postinfection but it showed significant reduction by 4 log cycles 24 h postinfection as compared to adjuvant control mice (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Bacterial burden in lungs. Groups of female Balb/c mice (n = 6) were immunized subcutaneously with 20 μg FilF formulated with CFA/IFA adjuvant on day 1, 14, and 21. The mice were intra-tracheally challenged with 108 CFU of A. baumannii ATCC 19606 at day 29. Immunization with FilF reduced the bacterial burden by 2 and 4 log cycles in the lungs of pneumonia model mice sacrificed 12 and 24 h post infection, respectively. The data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 6). p-value was determined by the one way analysis of variance (ANOVA). ***p < 0.001 (Adjuvant control vs. FilF immunized mice).

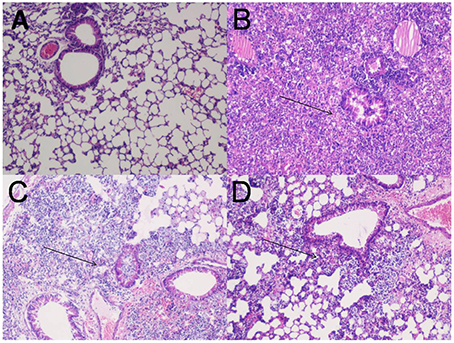

Histological Examination

Lungs of normal uninfected, adjuvant control and FilF immunized mice were removed 12 and 24 h post-infection, stained and visualized for histopathological changes (Figure 4). Bacterial challenge caused pneumonia and bacterial consolidation in the unimmunized mice. Lungs were filled with the increased number of lymphocytes and neutrophils 12 h post infection in unimmunized mice whereas immunized mice had moderate inflammation with infiltration of mixed mononuclear cells and neutrophils around peribronchial and perivascular areas. Moreover, lungs of immunized mice appeared normal with small number of neutrophils 24 h postinfection indicating that FilF immunization was able to limit the infection.

Figure 4. Lung histopathology. Groups of female Balb/c mice (n = 6) were immunized subcutaneously with 20 μg FilF formulated with CFA/IFA adjuvant on day 1, 14, and 21, and intra-tracheally challenged with 108 CFU of A. baumannii ATCC 19606 at day 29. The mice were sacrificed at 12 and 24 h post-challenge and lungs were collected for histopathology. (A) The lung from an unimmunized uninfected mouse showing normal histological characters. (B) Unimmunized infected mouse lung showing increased inflammatory cell infiltration in the perivascular and peribronchial areas, and within the airway lumen (arrows) 12 h postinfection. (C) The lung from an immunized infected mouse showing mild inflammatory cell infiltration in the perivascular and peribronchial areas (arrows) 12 h postinfection. (D) The lung from an immunized infected mouse showing significantly reduced infiltration of inflammatory cells 24 h postinfection. H&E, Magnification 100X.

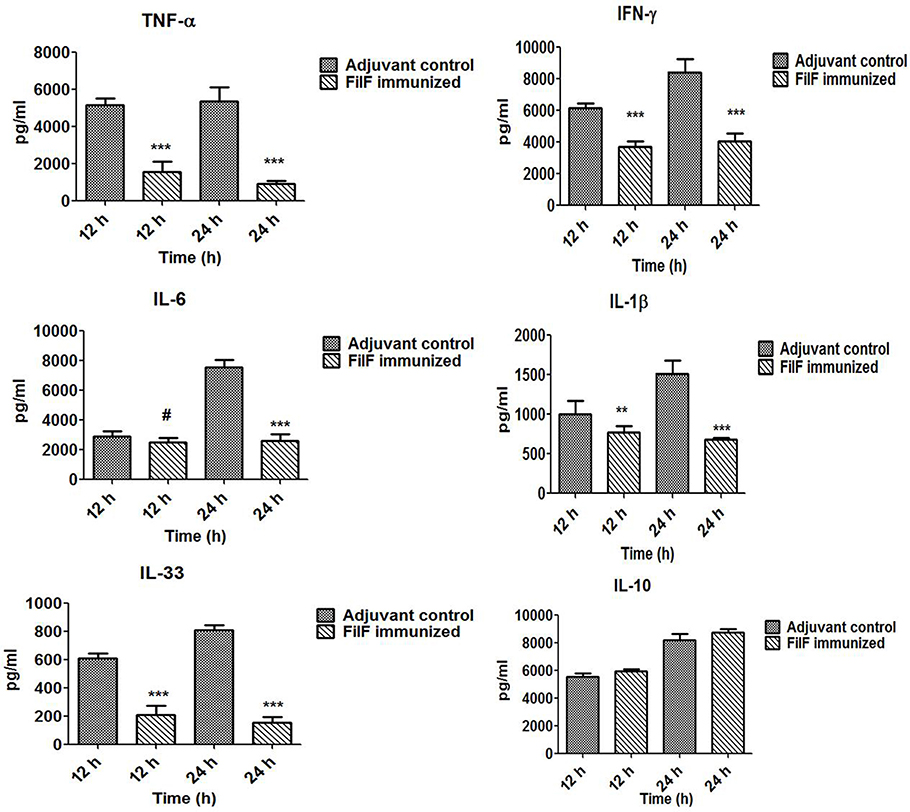

Effect of Immunization on Serum Cytokines Levels

Levels of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines were determined to check whether FilF immunization was able to prevent the release of these cytokines (Figure 5). Serum levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α (p < 0.001), IFN-γ (p < 0.001) and IL-1β (p < 0.05) were found to be significantly lower in immunized mice 12 h postinfection whereas IL-6 and anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 levels were comparable with unimmunized adjuvant control mice group. After 24 h postinfection, levels of all the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α (p < 0.001), IFN-γ (p < 0.001) and IL-1β (p < 0.001) were significantly low in immunized mice. However, IL-6 levels increased in adjuvant control and remained low in FilF immunized mice group 24 h postinfection (p < 0.001) (Figure 5). IL-10 levels remained comparable to unimmunized mice and the change was non-significant 24 h postinfection. Levels of IL-33, associated with the inflammatory responses of lung tissues, were also determined and interestingly, FilF immunized mice showed significantly low levels (p < 0.001) as compared to unimmunized mice 12 and 24 h postinfection.

Figure 5. Cytokine levels in the sera. Groups of female Balb/c mice (n = 6) were immunized subcutaneously with 20 μg FilF formulated with CFA/IFA adjuvant on day 1, 14, and 21. The mice were intra-tracheally challenged with 108 CFU A. baumannii ATCC 19606 at day 29, and sacrificed at 12 and 24 h post-challenge. The detection limit for all cytokines and chemokines is <10 pg/ml. p-value was determined by the one way analysis of variance (ANOVA). *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001, #non-significant, (Adjuvant control vs. FilF immunized mice).

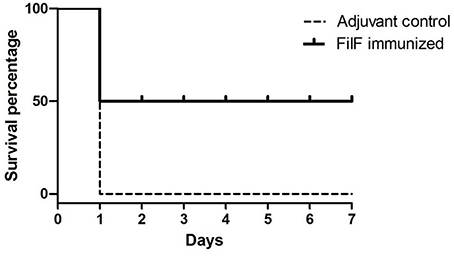

Survival against Challenge with Lethal Dose of A. baumannii

Effectiveness of FilF immunization was determined by determining the survival rate after challenge with lethal dose of A. baumannii. Groups of mice (n = 10) were immunized sub-cutaneously with 20 μg FilF formulated with CFA/IFA adjuvant on day 1, 14, and 21, and intra-tracheally challenged with 108 CFU of A. baumannii ATCC 19606 at day 29. The survival rate of mice was recorded continuously over the next seven days. FilF immunized (n = 10) mice showed improved survival rate as compared to unimmunized mice (n = 10) after challenge. All adjuvant control mice died within 24–48 h whereas FilF immunized mice showed 50% survival rate observed till seven days (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Survival rate of mice. Groups of female Balb/c mice (n = 10) were immunized sub-cutaneously with 20 μg FilF formulated with CFA/IFA adjuvant on day 1, 14, and 21, and intra-tracheally challenged with 108 CFU of A. baumannii ATCC 19606 at day 29. The survival rates of mice were recorded for seven days.

Discussion

Advances in bioinformatics have opened new possibilities for rapid identification of vaccine candidate proteins against MDR pathogens. Reverse Vaccinology (Rappuoli, 2001) has emerged as a robust method for identifying subunit vaccines and has been successfully used to develop vaccines against pathogens viz. Neisseria meningitidis (Pizza et al., 2000), Porphyromonas gingivalis (Ross et al., 2001), Streptococcus pneumoniae (Maione et al., 2005), Hepatitis C virus (Sarbah and Younossi, 2000) and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Ridzon and Hannan, 1999) showing its potential to be tested on the other emerging pathogens such as A. baumannii which is gaining attention of the medical world due to the rapid acquisition of multidrug resistance. Development of nonspecific immune response and chances of reverting back to virulent form dissuade the use of inactivated whole cells or outer membrane complexes. To generate specific immune response, outer membrane proteins such as porins, lipoproteins, ton-b receptors, biofilm associated proteins, transporter proteins or pilus proteins can be assessed as single subunit vaccine candidates. These outer membrane proteins are recognized as foreign by host immune system and are potential vaccine candidates against pathogens.

FilF is such a candidate protein predicted by in silico analysis of A. baumannii proteome. It is a putative pilus assembly protein and exact role in virulence is unknown but presence of FilF in virulent clinical isolates and in the outer membrane vesicles of invasive clinical strains makes it a crucial antigen (Mendez et al., 2012; Li et al., 2015). Bioinformatic analysis shows its localization in outer membrane, no transmembrane helices, high adhesion probability, conservation among the different strains of A. baumannii, presence of epitopes specific to the HLA alleles prevalent in north India (Rani et al., 2007) and dissimilarity with human and mouse proteome, thus presenting it as a highly potential vaccine candidate. B cell and T cell (MHC–I and MHC–II) epitopes in FilF were determined in order to assess its antigenicity and to look for the epitopes prevalent in north Indian population. Though FilF is well conserved among A. baumannii strains, yet determining the absolutely conserved regions containing the highly antigenic epitopes will tell about the protective immunity against all strains of A. baumannii and may lead to generation of a peptide vaccine by epitope stitching, which could be used to elicit immunity against a group of gram negative co-infecting pathogens.

To monitor immunoprotecive efficacy of FilF, a murine pneumonia model was established via intratracheal route. In case of A. baumannii, respiratory tract is the most common site of infection and colonization. Administration of bacteria to lungs through intranasal route produces bronchopneumonia and intratracheal route results in lobar pneumonia resulting in rise in cytokine levels and mice death (Joly-Guillou et al., 1997). But a major limitation of A. baumannii infection models (pneumonia and sepsis) is that mice clear the large proportion of the pathogen. Intranasal route was tried to establish the infection in mice with moderate (105) to high (108) CFU count but bacteria were cleared without causing the infection (results not shown). Later, intratracheal administration of optimized lethal dose of bacteria i.e., 108 CFU into mice caused infection resulting in mice death within 24–48 h. Such high dose (108 CFU) of A. baumannii could match the pathogenesis and virulence level of even the most virulent strain. Challenge with 108 CFU caused severe pulmonary infection in unimmunized mice and caused 100% mortality. FilF immunization elicited high humoral response resulting in decreased bacterial load, reduced levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and increased survival rate (50%) by controlling the severity of infection. Although survival rate of more than 50% has been reported by immunization with crude cell extract or outer membrane vesicles (McConnell et al., 2011; Huang et al., 2014) but the immunoprotective efficacy of subunit recombinant FilF is significant. Besides, bacterial burden in lungs was also significantly reduced by 2 and 4 log cycles, 12 and 24 h post challenge, respectively. This considerable reduction in bacterial loads is indicator of FilF efficacy. OMVs have FilF as a component and are effective vaccine formulations, but because of the complications of solubility, variability and low prevalence of antigens in OMVs, exploration of other vaccine candidates which may provide broad spectrum protection against this evolving pathogen is required. Identification and evaluation of individual vaccine candidates through immunoinformatics analysis of proteomes is an ideal choice for rational vaccine development. Recombinant FilF as antigen has advantages over inactivated whole cell or outer membrane vesicles such as the high levels of antigen purity, easy and reproducible large scale protein production, generation of specific immune response and absence of contaminating bacterial components such as lipopolysaccharide that could produce unwanted side effects. These attributes assist in the approval from regulatory agencies. OMVs contain many proteins which could affect the immune response generated by the effective antigens present in the formulation.

These results were further supported by histological evaluation of lungs. A. baumannii associated pneumonia can be identified by various disorders in the lung such as inflammation, bronchitis, abscess and edema. Oxidative stress and inflammation induced by this pathogen contribute to the death of lung epithelial cells (Smani et al., 2011). Reduced neutrophil infiltration in immunized mice as compared to unimmunized controls showed the efficacy of FilF. Interestingly, levels of IL-33 were significantly lower in immunized mice. IL-33, a critical mediator of the innate immune response, is released by epithelial cells on invasion by pathogen and initiates the immune response. It is supposed to play role in the recruitment of immune cells to the lungs and promotes bacterial clearance from the lungs of mouse in pneumonia model (Huang et al., 2014). Also, during infection, inflammation of lungs followed by increase in pro-inflammatory cytokine levels occurs due to the bacterial virulence factors such as pilus, porins, outer membrane proteins, lipopolysaccharides, capsular polysaccharides, proteases and nucleases. Pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 have been reported to play important role in cell death induced by A. baumannii. TNF-α binds to its specific receptor and initiates the caspase 8, 10, and 3 mediated apoptosis whereas IL-6 modulates expression of pro- or anti-apoptopic factors involved in the activation of intrinsic pathways of apoptosis (Smani et al., 2011). IFN-γ is a critical cytokine for innate and adaptive immunity against viruses and some bacterial pathogens. It activates macrophages and induces MHC II molecules (Schoenborn and Wilson, 2007). In this study, significant increase in the levels of pro-inflammatory type 1 (TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-1β), pro-inflammatory type 2 (IL-33) and anti-inflammatory type 2 cytokines was observed in unimmunized mice after bacterial challenge indicating the spread of infection. Increase in levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines has been observed in other immunoprotective studies and is related to the high bacterial load in organs (McConnell et al., 2010, 2011; Huang et al., 2014). The strong inflammatory response in unimmunized mice was possibly due to high bacterial challenging dose. FilF immunization, but not the adjuvant control, was able to reduce the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines significantly (Figure 4), that controlled the infection and decreased the damage to lung cells. But the levels of anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 remained comparable to unimmunized controls even after 24 h postinfection.

Antibody response is also a critical indicator to assess the effectiveness of a vaccine and FilF immunization evoked a high humoral response in mice. IgG antibody titer after first booster was >32,000 and after second booster reached >64,000. Anti-FilF antibodies may bind to A. baumannii surface and promote opsonization, phagocytosis and killing of the pathogen by macrophages and neutrophils. Moreover, antibody-mediated complement activation can lead to lysis of the pathogen and can also induce localized production of immune effector molecules that help to develop an amplified and more effective inflammatory response. FilF is a part of the specialized secretion system for the delivery of virulence factors in A. baumannii (Mendez et al., 2012). Anti-FilF antibodies could have bound to FilF and prevented the delivery of bacterial virulence factors to the host. Also, FilF is a putative pilus assembly protein, so anti-FilF antibodies, in addition to T cell activation, may bind to FilF and prevent the attachment of A. baumannii to the lungs of mouse, an initial and crucial step in establishment of A. baumannii, thus resulting in the enhanced survival of mice after challenge.

This is the first report on FilF immunoprotective efficacy and supports the significance of in silico prediction and in vivo validation of FilF, elicting strong protective response against A. baumannii. Compared to the earlier vaccine development efforts, FilF can be considered a promising vaccine candidate against infections caused by A. baumannii.

Conclusion

This work shows that FilF (i) is conserved among the strains of A. baumannii (ii) is a potential vaccine candidate predicted by in silico analysis (iii) raises high antibody titer in mouse (>64,000), (iv) reduces cytokine response [significant reduction in pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-33, IFN-γ, IL-6, and IL-1β (p < 0.001)], (v) protects mice from A. baumannii challenge (survival rate 50%) and (vi) reduces the severity of infection and bacterial burden in lungs of mice (4 log cycles reduction). These results underscore the potential of FilF as a vaccine candidate against rapidly emerging, multidrug resistant A. baumannii. FilF efficacy is further being examined by using virulent clinical strains, different animal models and human-friendly adjuvant such as alum. Also, it will be interesting to monitor the immunomodulatory potential of epitopes of FilF and comparison with the complete FilF protein.

Author Contributions

RS: performed all experiments and manuscript writing. NG: established intra-tracheal murine pneumonia model. GS: cytokines estimation and analysis. NC: checked and edited the manuscript. PS: overall guidance, designed the experiments and manuscript writing.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The author, RS, is thankful to Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), India for providing the research fellowship.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2016.00158

Supplementary Figure S1. Secondary structure prediction by Phyre2 and GOR IV showing amino acid wise secondary structures of FilF: alpha helix-119 amino acids, extended strand-153 amino acids and random coil-369 amino acids.

Supplementary Figure S2. Three-dimensional structure of FilF was predicted by I-TASSER and viewed by SPDBviewer.

Supplementary Figure S3. Ramachandran plot obtained from Procheck online tool showing the amino acids residues in plot.

Supplementary Figure S4. 0.7% agarose gel electrophoresis showing in Lane 1, lambda-HindIII marker; Lane 2, filF PCR product; Lane 3, purified recombinant pET28a-filF plasmid; Lane 4, pET28a-filF plasmid digested with XhoI; Lane 5, pET28-a plasmid digested with XhoI; Lane 6, Colony PCR for filF, using pET28a-filF as template.

Supplementary Table S1. Physico-chemical properties of FilF predicted by ProtParam.

Supplementary Table S2. Conservation of FilF among the strains of A. baumannii analyzed by BLASTp.

Supplementary Table S3. Genes present in Fil operon. Fil operon consists of six genes, mostly outer membrane proteins.

Supplementary Table S4. IEDB prediction of B cell epitopes.

Supplementary Table S5. IEDB presiction of MHC I binding epitopes for alleles prevalent in north India.

Supplementary Table S6. IEDB prediction of MHC II binding epitopes for alleles prevalent in north India.

References

Adams, M. D., Nickel, G. C., Bajaksouzian, S., Lavender, H., Murthy, A. R., Jacobs, M. R., et al. (2009). Resistance to colistin in Acinetobacter baumannii associated with mutations in the PmrAB two-component system. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53, 3628–3634. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00284-09

Bentancor, L. V., O'Malley, J. M., Bozkurt-Guzel, C., Pier, G. B., and Maira-Litrán, T. (2011). Poly-N-Acetyl-(1-6)-Glucosamine is a target for protective immunity against Acinetobacter baumannii infections. Infect. Immun. 80, 651–656. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05653-11

Chiang, M. H., Sung, W. C., Lien, S. P., Chen, Y. Z., Lo, A. F., Huang, J. H., et al. (2015). Identification of novel vaccine candidates against Acinetobacter baumannii using reverse vaccinology. Human Vaccin. Immunother. 11, 1065–1073. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2015.1010910

Coelho, J., Woodford, N., Turton, J., and Livermore, D. M. (2004). Multiresistant acinetobacter in the UK: how big a threat? J. Hosp. Infect. 58, 167–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2003.12.019

Corvec, S., Caroff, N., Espaze, E., Giraudeau, C., Drugeon, H., and Reynaud, A. (2003). AmpC cephalosporinase hyperproduction in Acinetobacter baumannii clinical strains. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 52, 629–635. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg407

Fattahian, Y., Rasooli, I., Mousavi Gargari, S. L., Rahbar, M. R., Alipour Astaneh Darvish, S., and Amani, J. (2011). Protection against Acinetobacter baumannii infection via its functional deprivation of biofilm associated protein (Bap). Microb. Pathog. 51, 402–406. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2011.09.004

Fournier, P. E., and Richet, H. (2006). The epidemiology and control of Acinetobacter baumannii in health care facilities. Clin. Infect. Dis. 42, 692–699. doi: 10.1086/500202

Garg, N., Singh, R., Shukla, G., Capalash, N., and Sharma, P. (2016). Immunoprotective potential of in silico predicted Acinetobacter baumannii outer membrane nuclease, NucAb. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 306, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2015.10.005

Goel, V. K., and Kapil, A. (2001). Monoclonal antibodies against the iron regulated outer membrane Proteins of Acinetobacter baumannii are bactericidal. BMC Microbiol. 1:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-1-16

He, Y., Xiang, Z., and Mobley, H. L. (2010). Vaxign: the first web-based vaccine design program for reverse vaccinology and applications for vaccine development. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2010:297505. doi: 10.1155/2010/297505

Huang, W., Yao, Y., Long, Q., Yang, X., Sun, W., Liu, C., et al. (2014). Immunization against multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii effectively protects mice in both pneumonia and sepsis models. PLoS ONE 9:e100727. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100727

Joly-Guillou, M. L. (2005). Clinical impact and pathogenicity of Acinetobacter. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 11, 868–873. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2005.01227.x

Joly-Guillou, M. L., Wolff, M., Pocidalo, J. J., Walker, F., and Carbon, C. (1997). Use of a new mouse model of Acinetobacter baumannii pneumonia to evaluate the postantibiotic effect of imipenem. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41, 345–351.

Laemmli (2011). Laemmli-SDSPAGE Bio-protocol Bio101: e80. Available online at: http://www.bio-protocol.org/e80

Li, J., Nation, R. L., Turnidge, J. D., Milne, R. W., Coulthard, K., Rayner, C. R., et al. (2006). Colistin: the re-emerging antibiotic for multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacterial infections. Lancet Infect. Dis. 6, 589–601. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70580-1

Li, Z. T., Zhang, R. L., Bi, X. G., Xu, L., Fan, M., Xie, D., et al. (2015). Outer membrane vesicles isolated from two clinical Acinetobacter baumannii strains exhibit different toxicity and proteome characteristics. Microb. Pathog. 81, 46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2015.03.009

Luo, G., Lin, L., Ibrahim, A. S., Baquir, B., Pantapalangkoor, P., Bonomo, R. A., et al. (2012). Active and passive immunization protects against lethal, extreme drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infection. PLoS ONE 7:e29446. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029446

Maione, D., Margarit, I., Rinaudo, C. D., Masignani, V., Mora, M., Scarselli, M., et al. (2005). Identification of a universal Group B streptococcus vaccine by multiple genome screen. Science 309, 148–150. doi: 10.1126/science.1109869

McConnell, M. J., Domínguez-Herrera, J., Smani, Y., López-Rojas, R., Docobo-Pérez, F., and Pachón, J. (2010). Vaccination with outer membrane complexes elicits rapid protective immunity to multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Infect. Immun. 79, 518–526. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00741-10

McConnell, M. J., Hanna, P. C., and Imperiale, M. J. (2006). Cytokine response and survival of mice immunized with an adenovirus expressing Bacillus anthracis protective antigen domain 4. Infect. Immun. 74, 1009–1015. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.2.1009-1015.2006

McConnell, M. J., and Pachón, J. (2010). Active and passive immunization against Acinetobacter baumannii using an inactivated whole cell vaccine. Vaccine 29, 1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.10.052

McConnell, M. J., Rumbo, C., Bou, G., and Pachón, J. (2011). Outer membrane vesicles as an acellular vaccine against Acinetobacter baumannii. Vaccine 29, 5705–5710. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.06.001

Mendez, J. A., Soares, N. C., Mateos, J., Gayoso, C., Rumbo, C., Aranda, J., et al. (2012). Extracellular proteome of a highly invasive Multidrug-resistant clinical strain of Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Proteome Res. 11, 5678–5694. doi: 10.1021/pr300496c

Moriel, D. G., Beatson, S. A., Wurpel, D. J., Lipman, J., Nimmo, G. R., Paterson, D. L., et al. (2013). Identification of novel vaccine candidates against multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. PLoS ONE 8:e77631. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077631

Peleg, A. Y., Seifert, H., and Paterson, D. L. (2008). Acinetobacter baumannii: emergence of a successful pathogen. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 21, 538–582. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00058-07

Pizza, M., Scarlato, V., Masignani, V., Giuliani, M. M., Aricò, B., Comanducci, M., et al. (2000). Identification of vaccine candidates against serogroup B meningococcus by whole-genome sequencing. Science 287, 1816–1820. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5459.1816

Qureshi, Z. A., Hittle, L. E., O'Hara, J. A., Rivera, J. I., Syed, A., Shields, R. K., et al. (2015). Colistin-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: beyond carbapenem resistance. Clin. Infect. Dis. 60, 1295–1303. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ048

Rani, R., Marcos, C., Lazaro, A. M., Zhang, Y., and Stastny, P. (2007). Molecular diversity of HLA-A, -B and –C alleles in a North Indian population determined by PCR-SSOP. Int. J. Immunogenet. 34, 201–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-313X.2007.00677.x

Rappuoli, R. (2001). Reverse vaccinology, a genome-based approach to vaccine development. Vaccine 19, 2688–2691. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(00)00554-5

Ridzon, R., and Hannan, M. (1999). Tuberculosis vaccines. Science 286, 1298–1300. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5443.1297e

Rodriguez-Martinez, J. M., Nordmann, P., Ronco, E., and Poirel, L. (2010). Extended-spectrum cephalosporinase in Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54, 3484–3488. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00050-10

Rolain, J. M., Roch, A., Castanier, M., Papazian, L., and Raoult, D. (2011). Acinetobacter baumannii resistant to colistin with impaired virulence: a case report from France. J. Infect. Dis. 204, 1146–1147. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir475

Ross, B. C., Czajkowski, L., Hocking, D., Margetts, M., Webb, E., Rothel, L., et al. (2001). Identification of vaccine candidate antigens from a genomic analysis of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Vaccine 19, 4135–4142. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(01)00173-6

Sambrook, J., and Russell, D. W. (2001). Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 3rd Edn. New York, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press.

Sarbah, S. A., and Younossi, Z. M. (2000). Hepatitis C: an update on the silent epidemic. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 30, 125–143. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200003000-00005

Schoenborn, J. R., and Wilson, C. B. (2007). Regulation of interferon-gamma during innate and adaptive immune responses. Adv. Immunol. 96, 41–101. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(07)96002-2

Keywords: Acinetobacter baumannii, FilF, OMP, vaccine, reverse vaccinology, cytokines, immunoprotection

Citation: Singh R, Garg N, Shukla G, Capalash N and Sharma P (2016) Immunoprotective Efficacy of Acinetobacter baumannii Outer Membrane Protein, FilF, Predicted In silico as a Potential Vaccine Candidate. Front. Microbiol. 7:158. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00158

Received: 09 November 2015; Accepted: 29 January 2016;

Published: 12 February 2016.

Edited by:

Amy Rasley, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, USAReviewed by:

Yongqun “Oliver” He, University of Michigan, USAMarisa Mariel Fernandez, University of Buenos Aires and CONICET, Argentina

Copyright © 2016 Singh, Garg, Shukla, Capalash and Sharma. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Prince Sharma, princess@pu.ac.in

Ravinder Singh1

Ravinder Singh1 Prince Sharma

Prince Sharma