- Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics, John A. Burns School of Medicine (JABSOM), University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI, USA

Introduction: Recently, three independent, intercorrelated biophysical measures have provided the first quantitative measures of a binary form of behavioral laterality called “Hemisity,” a term referring to inherent opposite right or left brain-oriented differences in thinking and behavioral styles. Crucially, the right or left brain-orientation of individuals assessed by these methods was later found to be essentially congruent with the thicker side of their ventral gyrus of the anterior cingulate cortex (vgACC) as revealed by a 3 min MRI procedure. Laterality of this putative executive structural element has thus become the primary standard defining individual hemisity. Methods: Here, the behavior of 150 subjects, whose hemisity had been calibrated by MRI, was assessed using five MRI-calibrated preference questionnaires, two of which were new. Results: Right and left brain-oriented subjects selected opposite answers (p > 0.05) for 47 of the 107 “either-or,” forced choice type preference questionnaire items. The resulting 30 hemisity subtype preference differences were present in several areas. These were: (1) in logical orientation, (2) in type of consciousness, (3) in fear level and sensitivity, (4) in social-professional orientation, and (5) in pair bonding-spousal dominance style. Conclusions: The right and left brain-oriented hemisity subtype subjects, sorted on the anatomical basis of upon which brain side their vgACC was thickest, showed 30 significant differences in their “either-or” type of behavioral preferences.

Introduction

Hemisphericity (Bogen, 1969), is a once popular but now discredited (Beaumont et al., 1984) concept of behavioral laterality where each individual's thinking and behavioral style was supposed to occupy a unique point upon a gradient between right and left brain extremes. This definition was fundamentally flawed because the behavioral outcome of most subjects was near the middle of the gradient, giving these studies essentially no analytical or predictive power. However, over the subsequent quarter of a century since the demise of hemisphericity, evidence has been accumulating that robust different right or left brain-oriented thinking and behavioral styles do indeed exist. What was required to reveal these differences was the replacement of the gradient context of “hemisphericity” by the binary context of “hemisity” where each individual is either left or right brain-oriented with no intermediates possible. This was accomplished in part by the use of forced choice binary questions.

Based on this binary concept, three independent, but highly intercorrelated biophysical methods (dichotic deafness, two-hand line bisection, two-hand mirror tracing) have shown persistent significant differences between individuals (Morton, 2001, 2002, 2003a,b,c). The results of these methods were confirmed and amplified by the MRI demonstration that the ventral region of the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex was thickest on the same side of the subject's brain as their biophysically predetermined hemisity [in 130 of 133 subjects (98%), Morton and Rafto, 2010].

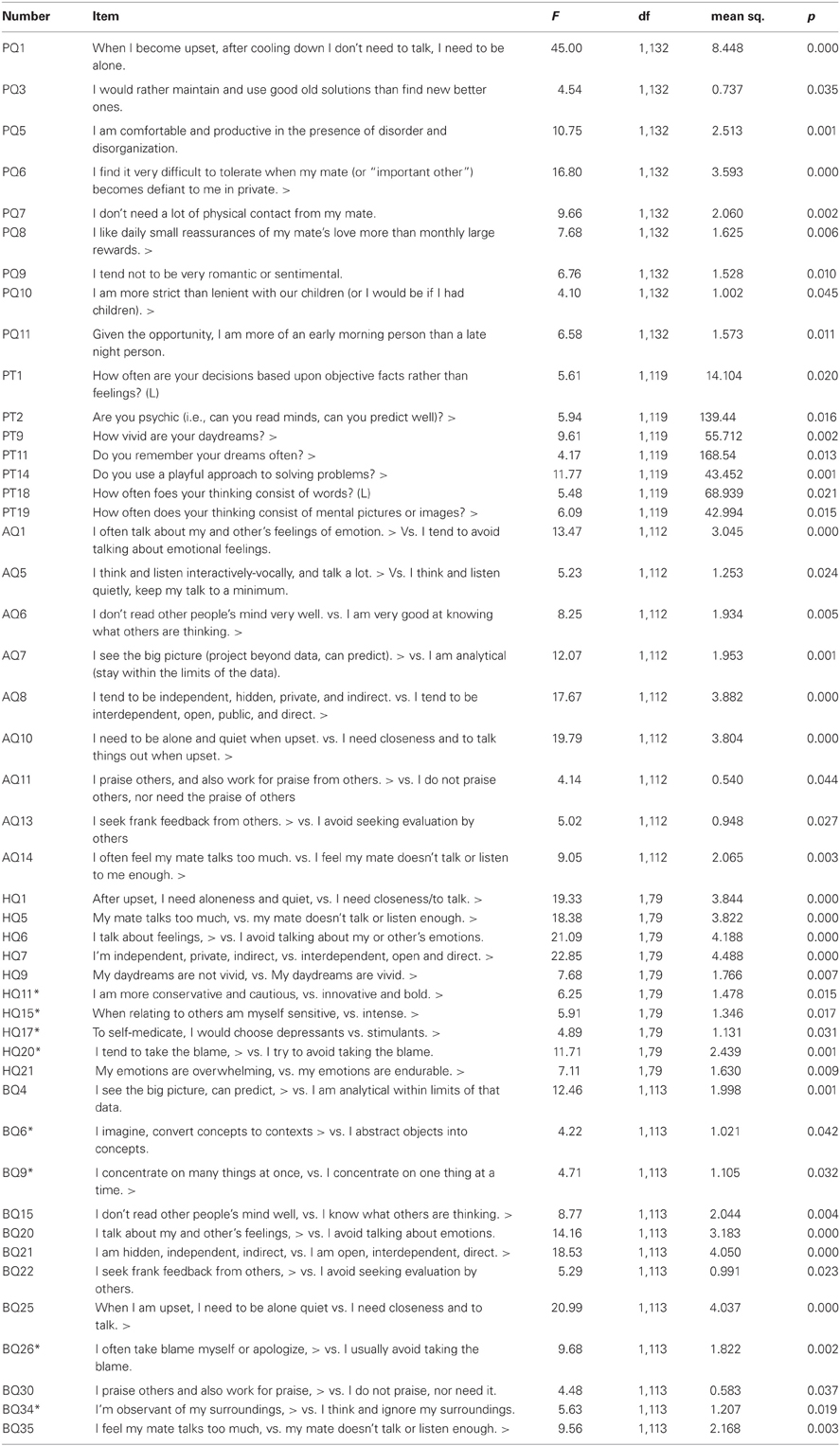

With the ability to accurately determine the right or left brain individual hemisity subtype identity in hand, the time has come to answer some very interesting questions: Do these biophysically identified right and left hemisity subtype individuals differ significantly in their behavioral preferences? And if so, specifically how? To approach this question, the same 133 multiply determined hemisity subtype subjects were assessed, based upon their answers to five behavioral preference questionnaires, three published (Zenhausern, 1978; Morton, 2002, 2003c), and two new ones reported here. A surprisingly large number of these “either-or” choices were answered oppositely by the two hemisity subtype subjects. Morton (2003d) has reported that a hemisity sorting occurred as college freshmen migrated through college, graduate school, and into 15 professions.

Methods

Subjects

Subjects (n = 133) were volunteers from the University of Hawaii community, 44.0 years mean age, ± 14.5 years S.D. Of these, 47.3% (63) were female, 11% (15) claimed left-handedness, and 77% (103) were Caucasian, the rest being predominantly Asian. Based upon an earlier MRI study (Morton and Rafto, 2010), there were 45.1% (60) right brain-oriented persons (RPs) composed of 48.3% (29) right brain-oriented females (RFs) and 51.7% (31) right brain-oriented males (RMs). The 54.9% (73) left brain-oriented persons (LPs) consisted of 47.9% (35) left brain-oriented females (LFs) and 52.1% (38) left brain-oriented males (LMs). The Committee of Human Studies of the University of Hawaii Institutional Review Board had earlier approved all appropriate elements of this unfunded research.

The Five Behavioral Preference Questionnaires

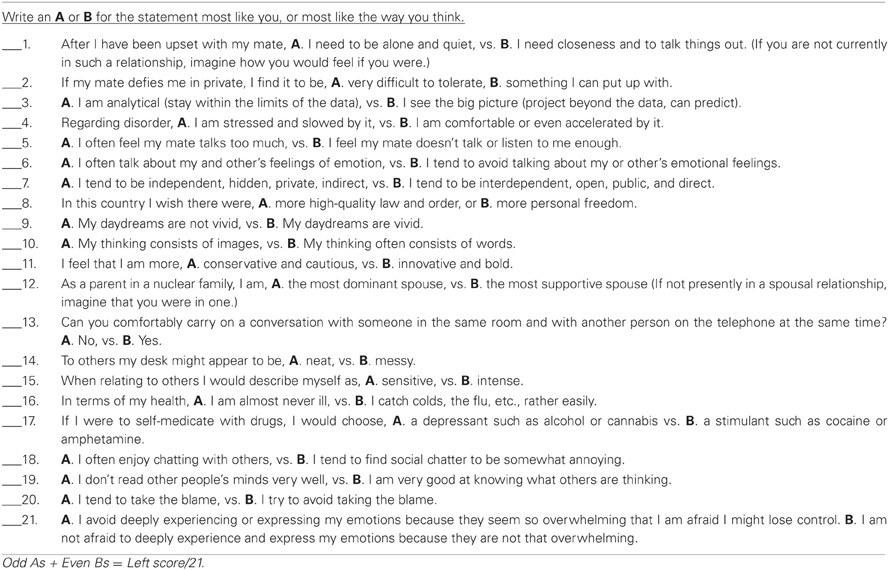

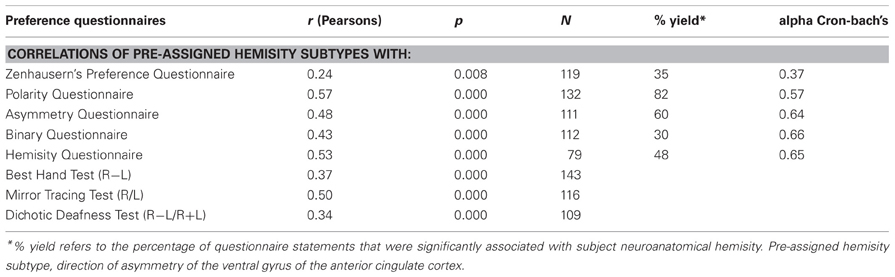

Subjects completed the five preference questionnaires. In Table 1, these were compared for reliability and for overall correlation with the predetermined subject hemisity subtype. They were Zenhausern's (1978) “Preference Questionnaire,” Morton's “Polarity Questionnaire (PQ)” (Morton, 2002) and the Asymmetry Questionnaire (AQ) (Morton, 2003c). The new Binary Questionnaire (BQ) (Appendix 1) and new Hemisity Questionnaire (HQ) (Appendix 2) were also filled out.

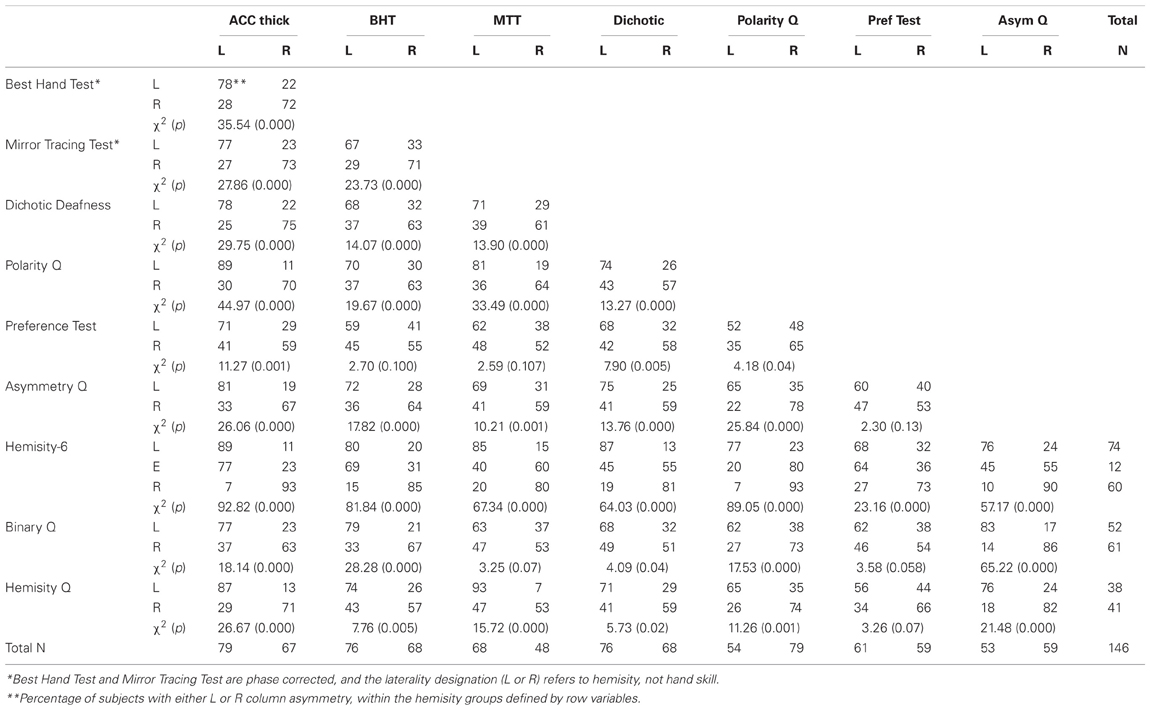

Table 1. Overall correlations and reliability of preference questionnaire scores with predetermined subject hemisity subtype.

Statistics

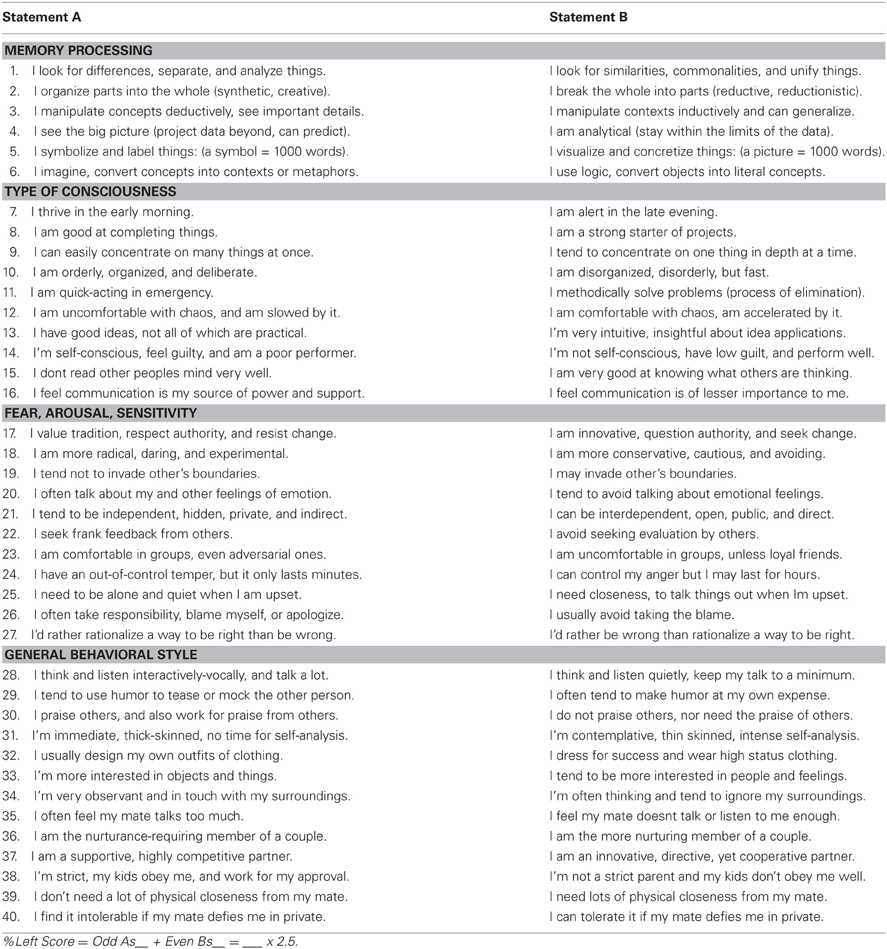

The internal reliabilities of the questionnaires were assessed by Cronbach's alpha. Pearson correlations were used to assess the association between overall scores on the five questionnaire measures (as well as continuous measures derived from each of the three biophysical hemisity measures) and with the pre-assigned hemisity subtype of the 133 subjects. One-Way analysis of variance were used to determine which items in the five questionnaires differed significantly between right and left hemisity subtype participants using SPSS statistical software. Of the 107 questionnaire items, 32 non-overlapping items showed significant differences in preference between left and right brain-oriented subjects (Table 4). Four items were collapsed into two binary concepts. The 30 binary items for which these MRI-calibrated hemisity subtype subjects differed were sorted into five arbitrary hemisity behavioral categories in Table 5.

Results

Overall correlations of the five preference questionnaires with predetermined subject hemisity subtype (Table 1) ranged from −0.24 for Zenhausern's Preference Questionnaire, to −0.57 for the PQ, with the AQs, BQs, and HQs falling in between at Pearson's r values of = −0.48, −0.43, and −0.53, respectively. Of these five questionnaires, the 11 true false statement PQ was the most efficient solo instrument with 82% of the items (9/11) showing significant associations with predetermined hemisity. Cronbach's alpha values of the tests (Table 1) ranged from 0.37 to 0.66, indicating that more than one of these questionnaires would be required to determine individual hemisity, if this were to be the sole method of assessment. As a comparison, the three biophysical hemisity assays were also included at the bottom of the table.

The associations among the six secondary hemisity instruments (three biophysical and three psychometric), as well as hemisity, determined by the average hemisity outcome of the combination of these six binary assays (Hemisity-6), by the two additional questionnaires (BQ and HQ), and hemisity determined by anterior cingulate MRI asymmetry were examined using cross tabulations and chi square analyses (Table 2). As may be seen, the pre-assigned hemisities were very strongly associated with hemisity classifications based on the three biophysical methods, all five questionnaires, and the combination of the six secondary methods (Hemisity-6). All three of the biophysical methods were strongly associated with each of the others. The summary measure of hemisity (Hemisity-6) was strongly associated with all of the other hemisity measures. The PQs, AQs, and HQs were strongly associated with each of the other classifications. The BQ classification was significantly associated with nine of the other hemisity classifications, while the associations with two others [Mirror Tracing Test, Preference Test (PT)] reached only trend levels of significance. The classification based on Zenhausern's earlier PT (1978) was significantly associated with six of the other hemisity classifications. But, as expected, it was associated with the BQ and HQ classifications at only a trend level of significance, and was not associated with classifications based on the Best Hand Test, Mirror Tracing Test, or AQ.

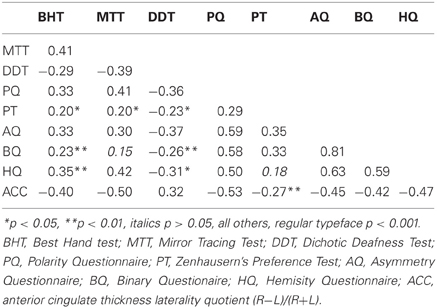

A continuous measure of neuroanatomical asymmetry derived from predetermined hemisity was significantly correlated with continuous measures of asymmetry derived from the Best Hand Test, Mirror Tracing Test, Dichotic Deafness Test, PQs, AQs, BQs, and HQs, and the PT (Table 3). All of the continuous measures derived from these hemisity determination methods (degree of leftness) were significantly intercorrelated, with the exception of the correlations between the Mirror Tracing Test and BQ, and the PT and HQ. Thus, for the most part, all nine of these asymmetries were strongly associated with each of the others, as only two of the 36 correlations among these nine variables failed to reach significance. The marking of some of the data with a negative sign is an artifact of the original definitions of the instruments involved.

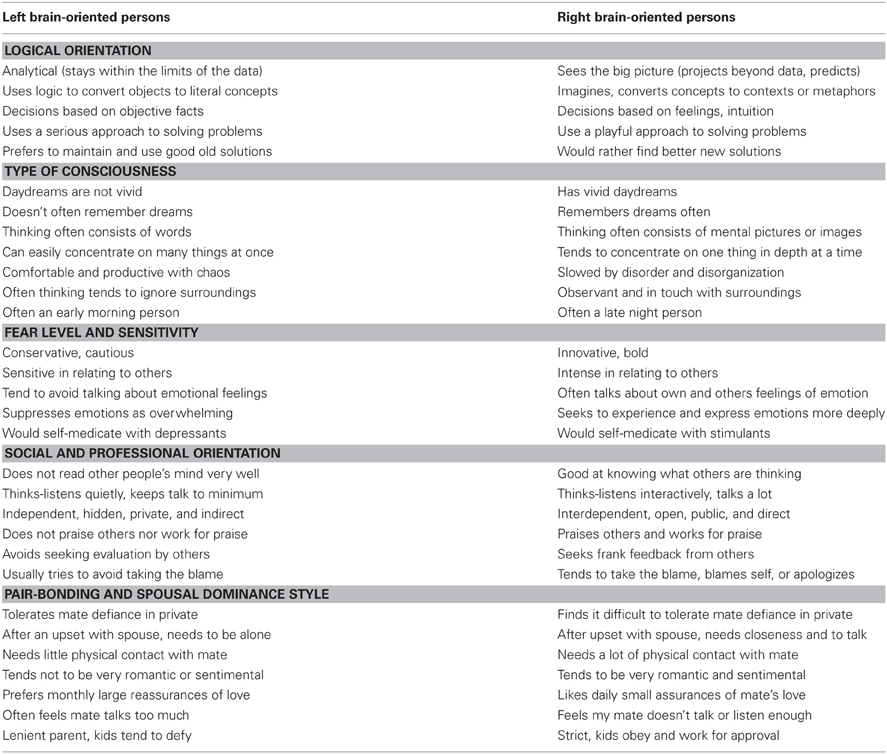

Table 4 lists the 47 questionnaire items which showed a significant difference between participants with Left > Right vs. those with Right > Left ventral gyrus of the anterior cingulate cortex (vgACC) thickness. Since the BQ and the HQ contained items that were also included (or very similar in content) in Zenhausern's PT, PQ and AQs, 15 redundant items were deleted, and two items were collapsed into a single binary item, leaving 30 binary items showing significant associations with anterior cingulate asymmetry. For example, asterisks in the lower part of Table 4 indicate which of the items were unique to the new BQs and HQs. Attempts to derive item groupings empirically using factor analysis yielded 17 factors for the 47 significant items and 12 factors for the 30 non-redundant items, which were difficult to interpret. Therefore, these items were grouped into five domains, on a priori grounds (Table 5). These were: (1) logical orientation, (2) type of consciousness, (3) fear level and sensitivity, (4) social-professional orientation, (5) pair bonding-spousal dominance style.

Table 4. Forty-seven items showing significant differences between left vs. right greater vgACC thickness.

Discussion

Recently, it became possible to segregate people into an anatomical-behavioral dichotomy, called hemisity. This was made possible by use of three biophysical methods (Morton, 2001, 2002, 2003a,b). As the result of further extension of this research, hemisity can now be determined, based upon which side of an individual's vgACC is thickest, as revealed by a 3 min MRI scan (Morton and Rafto, 2010). These four methods were earlier used to separate a subset of the subjects of this study into two groups: LPs and RPs. This enabled us to approach a most interesting question about hemisity: what thinking and behavioral style differences exist between right and left brain-oriented hemisity subtypes.

The goal of this research was to inquire whether RPs in general had any behavioral preferences in common that were different or opposite to those of LPs. To this end, five behavioral preference type questionnaires, three containing non-overlapping “either-or” forced choice type of binary statements (Morton, 2002, 2003c) and two new ones reported here (Appendix 1 and 2), were administered to the MRI-calibrated members of these two hemisity subgroups. The outcome was that the right and left brain-oriented hemisity groups choose statistically significant opposite responses for 47 of the 107 questionnaire items. Eliminating redundant items and collapsing two items into one binary concept yielded 30 non-redundant behavioral characteristics. These behavioral preference differences occurred in five areas: (1) logical orientation, (2) type of consciousness, (3) fear level and sensitivity, (4) social-professional orientation, and (5) pair bonding-spousal dominance style (Table 5). There follows a brief discussion of how these results may be related to many previously studied psychological, personality, health and mental health topics.

Logical Orientation

Local—global

Consistent with the much discussed local vs. global anatomy and putative opposite function of the left and right cerebral hemispheres (review by Ivry and Robertson, 1998), the LPs in this study showed a local processing bias, compared to the global bias of the RPs. If this dichotomy associated with hemisity is indeed mediated by hemispheric asymmetry of local vs. global processing, it is hypothesized that future studies should find a local processing advantage in subjects with left hemisity, and a global processing advantage in subjects with right hemisity.

Logical—intuitive

In keeping with earlier studies (Prifitera, 1981), since the hemisity subtypes show analytic/logical vs. gestalt/holistic preferences, it is also hypothesized that right hemisity will be associated with higher scores on intuition, feeling, perceiving, and/or extraversion, while left hemisity will be associated with higher scores on sensing, thinking, judging, and/or introversion on Jungian personality types, as measured by the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI). In this semantic context, “feeling” is a gut estimate subjective opinion, while “sensing” is a quantitative analysis based upon measurement. This may be tested by the greater ability of RPs to accurately assess values objectively from only qualitative data. Without measurement, LPs tend to be less accurate in such estimation.

Verbalizer—visualizer

Here, left hemisity is associated with a preference for thinking in words, while right hemisity is associated with a preference for thinking in pictures, suggesting that hemisity is related to the “verbalizer—visualizer” distinction. Consistent with many earlier studies (Richardson, 1977, 1978; Montgomery and Jones, 1984), it is hypothesized that right hemisity will be associated with a predominantly visualizer style, while left hemisity will be associated with a predominantly verbalizer style.

Type of Consciousness

Transliminality

Similarly, LPs and RPs were significantly different in their choices regarding the elements considered to be associated with consciousness. That LPs indicated having non-vivid daydreams and rare recall of dreams, places them opposite to RPs with more vivid daydreams and common recall of dreams. This suggests that LPs have a greater barrier to the unconscious and that the RPs in contrast are the more transliminal. Transliminality is the relative tendency for psychological material to cross thresholds into or out of consciousness. Transliminality is strongly associated with sleep-related experiences. Scores on the Iowa Sleep Experiences Scale were significantly correlated with several measures of schizotypy, measures of dream recall frequency, openness to experience, fantasy proneness, and absorption (Fassler et al., 2006). It is hypothesized that right hemisity will be associated with higher scores on the Iowa Sleep Experiences Scale. It is further hypothesized that right hemisity will be associated with higher scores on the Revised Transliminality Scale (Thalbourne et al., 1997).

Absorption

It is interesting that LPs seem to be able to concentrate on many things at once and thrive on chaos, while RPs appear to think deeply on only one thing at a time in a form of absorption (Tellegen and Atkinson, 1974) and appear to be distracted by disorder. It is hypothesized that right hemisity will be associated with higher scores on measures of absorption and hypnotizability.

Mindfulness

The association of right hemisity with a greater awareness of one's surroundings suggests a possible association between right hemisity and the trait of mindfulness. An operational definition of mindfulness as “the awareness that emerges through paying attention on purpose, in the present moment and non-judgmentally to the unfolding of experience moment by moment” was proposed by Kabat-Zinn (2003). Attention and cognition are critically involved in mindfulness (Malinowski, 2008), which entails self-regulation of attention and orientation toward one's experiences. It is hypothesized that right hemisity will be associated with higher scores on measures of trait mindfulness.

Fantasy proneness

Fantasy proneness is also associated with vividness of visual imagery (van de Ven and Merckelbach, 2003). It is hypothesized that right hemisity will be associated with higher scores on measures of fantasy proneness.

Morningness—eveningness

The association of morningness with left hemisity and eveningness with right hemisity here is consistent with other literature correlates of chronotype too numerous to cite here, such as (Adan and Almirall, 1992 or Muro et al., 2009). Eveningness is significantly associated with extraversion, impulsivity, externalizing behaviors, lower self-control, higher novelty seeking, greater sensation seeking, greater risk-taking propensity, greater openness to experience, a greater sense of humor, and more frequent nightmares. Eveningness is also associated with greater depressive symptoms, subclinical manic symptoms, and a greater tendency to bipolar disorder. Both depressive and manic tendencies are components of transliminality.

Morningness is associated with greater introversion, conscientiousness, and anxiety than eveningness. Morningness is associated with higher baseline arousal levels than eveningness, as indicated by higher mean waking and daytime cortisol levels, higher levels of energetic arousal, and lower immunity. It is predicted that right hemisity will be associated with eveningness, while left hemisity will be associated with morningness, as measured by the Morningness–Eveningness Questionnaire (Horne and Ostberg, 1976).

Alexithymia

Left hemisity is associated with a tendency to avoid talking about feelings. A syndrome named “alexithymia” has been described as characterized by an inability to verbally describe feelings, flattened affect, inability to recognize emotions in others, absence of fantasies and dreaming, preoccupation with minute details of external events, somatic complaints, and withdrawn personality traits (Sifneos et al., 1977). Studies of commisurotomized patients suggest that the dissociation between affect and cognition seen in alexithymia is related to a functional deconnection of the hemispheres (Hoppe and Bogen, 1977). A clinical study of a patient with agenesis of the corpus callosum revealed severe alexithymia (Buchanan et al., 1980). Increased size of the corpus callosum may be associated with greater interhemispheric communication (Christman, 1995). Right hemisity is associated with a larger area of the corpus callosum (Morton and Rafto, 2006), and with lower levels of alexithymia. It is predicted that left hemisity will be associated with higher scores on the Toronto Alexithymia Scale (Bagby et al., 1994).

Repressors

A repressive defense style, i.e., preferential use of the defense mechanism of repression has been found to be associated with relatively greater left hemisphere activation (Waldinger and Van Strien, 1995). A repressive coping style has been psychometrically identified in terms of high scores on the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale (MCSDS) and low scores on anxiety scales (Tomarken and Davidson, 1994). It was associated with inhibition of the perception of threat, repression of experiences of negative affect, and use of a self-regulatory style that promotes self-esteem. This involved a self-serving attributional style, a self-serving hindsight bias, impaired memory of negative self-relevant feedback and negatively toned autobiographical events. It also showed a preference for defense mechanisms characterized by the inhibition of interpersonal conflict and ambivalent or negative emotions, and by selective accentuation of the positive (Schwartz, 1990). Tomarken and Davidson (1994) and several others found that compared to low anxious and high anxious subjects, repressors had significantly greater left frontal EEG activation, heightened autonomic responsivity and systolic blood pressure. The repressive coping style may be associated with a functional hemispheric deconnection (Schwartz, 1990). Consistent with the deconnection hypothesis, Davidson (1984) found that repressors showed relative deficits in interhemispheric transfer of negative affective information from the right to the left hemisphere. Thus, both relatively greater left frontal activation and reduced cross-callosal transfer of negative affective information appear to be associated with repressive coping style. It is here predicted that left hemisity will be associated with a repressive style, as indicated by high scores on measures of social desirability, and low scores on measures of anxiety on the MCSDS (Tomarken and Davidson, 1994).

Fear Level and Sensitivity

Anxiety—confidence

As an element that seemed to underlie many of the choices in this and other sections of the analysis, it appears that the LPs were more anxiety prone than RPs. Here, this was suggested by choices between feeling conservative and cautious vs. innovative and bold. It was also reflected in feeling sensitive vs. bold in personal relations, suggestive of personal dominance issues. Again, LPs preferred to avoid experiencing and talking about their and others emotions while the RPs appeared to revel in doing so. It is hypothesized that left hemisity will be associated with higher scores on anxiety ranking scales such as Spielberger's State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (trait version) and to be more prone to anxiety-based stress-induced opportunistic illnesses, chronic fatigue syndrome, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Social and Professional Orientation

Extroversion-introversion

Several of the items in the social and professional orientation cluster suggest an association between left hemisity with introversion and between right hemisity with extraversion. Introversion is associated with greater cerebral blood flow while extraversion with less CBF (Mathew et al., 1984), consistent with higher cortical arousal levels in introverts. Introverts exhibited a non-verbal decoding deficit, relative to extraverts, possibly suggesting relatively lesser right than left hemisphere functioning in introverts (Lieberman and Rosenthal, 2001). Introverts tend to show hyper-anxious Type A behavior that is also associated with a tendency to repress stimulation in order to down regulate excessive baseline arousal (Ludvigh and Happ, 1974), leading them to self-medicate with depressants and consequent proneness to alcoholism (Morton, 2011, 2012). Extroverts, in contrast, to compensate for low baseline arousal, seek out stimulation in order to up regulate cortical arousal to optimum levels. As found here, RPs appear to prefer stimulating substances over depressants (Morton, 2011, 2012). Previously cited studies indicated that higher baseline arousal is also associated with morningness, alexithymia, and a repressive style, all of which are characteristic of left hemisity. Extraversion has been found to be significantly associated with various characteristics associated with transliminality and right hemisity, including creativity and mania/hypomania (Cassano et al., 2009). Extraversion is also associated with higher levels of emotional awareness (Igarashi et al., 2011) and right hemisity is associated with greater emotionality.

Theory of mind abilities

Theory of mind is the ability to make inferences about the intentions, feelings, and beliefs (mental states) of others and to use these inferences to predict and control behavior (Premack and Woodruff, 1978). Theory of mind abilities have been found to be associated with various aspects of non-literal language, including metaphor, humor, irony, and sarcasm (Langdon et al., 2002; Channon et al., 2005). Right hemisity is associated with an evidence-based belief in a greater ability to know what others are thinking. Patients with right hemisphere damage have been shown to be impaired in the comprehension of similes, metaphors, proverbs, sarcasm, humor, and other non-literal inferences (Brownell et al., 1990). Both affective prosody and sarcasm perception are thought to depend on the right hemisphere (Shamay-Tsoory et al., 2005). The right frontal lobe, particularly the ventral medial region, is pre-eminently involved in the mediation of theory of mind abilities and self-awareness (Stuss et al., 2001). Impairments on theory of mind tasks have also been found in patients following right hemisphere stroke (Happé et al., 1999). It is hypothesized that right hemisity will be associated with better performance on Theory of Mind tasks.

Pair Bonding and Spousal Dominance Style

Attachment

The items included in the pair bonding and spousal dominance cluster refer to behaviors related to attachment style, suggesting that right hemisity is associated with greater activation of the behavioral attachment system, while left hemisity is associated with lower activation of the behavioral attachment system. Theoretical arguments and empirical studies have suggested that attachment behaviors are mediated predominantly by the right hemisphere, particularly the right orbitofrontal cortex (Mohr et al., 2008). As demonstrated by the present data, it is predicted that left hemisity will be associated with an avoidant spousal attachment style, while right hemisity will be associated with a more dominant spousal attachment style.

Limitations and Opportunities

Although Zenhausern's Preference Questionnaire was one of the best from the hemisphericity era instruments, it was substantially weaker than the four other HQs derived from the more recent biophysical methods used here. It employed a Likert (1932) type of rating scale. Because of a tendency to avoid making critical choices by marking intermediate values, this approach may have contributed to the statistical downfall of earlier hemisphericity studies (Beaumont et al., 1984). Generation and use of the other four forced choice binary response HQs used here has markedly improved their reliability. Yet, while raising Cronbach's alpha measures of internal and external reliability from about 0.37 into the 0.54–0.66 range, the latter still leave something to be desired in terms of the 0.9 alpha value commonly accepted as indicative of high specificity. However, the reconceptualization of hemisity as a typological dichotomy suggests that high internal consistency may not be an appropriate measure of psychometric adequacy, as internal consistency is more relevant to measures of trait dimensions. The HQs may be better thought of as taxonic indicators, which frequently include multiple relatively independent items related to taxon membership (e.g., Golden and Meehl, 1979).

The unpublished BQs and HQs (Appendix 1 and 2) were collections of guesses made as to how left brain-oriented individuals might differ. They were included here because they ended up providing several additional items where hemisity subtypes chose opposite answers to a significant extent. They were not as specific as the published PQs and AQs (Morton, 2002, 2003c). Nevertheless, the numbers of subjects in this study enabled the individual items in each of the five questionnaires to provide significant correlations for 47 of the test items (yielding 30 non-redundant binary concepts), thus opening a window to investigating personality differences between right and left brain-oriented individuals. It is expected that more contrasting behaviors of hemisity will be found. It must be stated that the probability that a specific hemisity subtype will have any one of these 30 specific traits is approximately eighty percent. That is, about one in five RPs will be morning larks, while the other four will be night owls.

Conclusions

Recently, three independent, intercorrelated biophysical measures have provided the first quantitative measures of a binary form of hemisphericity, called “Hemisity,” a term referring to inherent opposite right or left brain-oriented differences in thinking and behavioral styles. The right or left brain-orientation of individuals assessed by these methods was later found to be essentially congruent with the thicker side of their vgACC (Morton and Rafto, 2010). Here, the behavioral preferences of 133 subjects, whose hemisity subtype had been determined repeatedly in previous reports, were assessed using five preference questionnaires, two of which were new. Right and left brain-oriented subjects selected opposite answers (p > 0.05) for 47 of the 107 “either-or” type preference questionnaire items, which were reduced to 30 binary preferences by elimination of redundant items. The thirty hemisity subtype preference differences occurred in five general areas: logical orientation, type of consciousness, fear level and sensitivity, social-professional orientation, and pair bonding-spousal dominance style. The right and left brain-oriented hemisity subtype subjects, showed numerous significant differences in their “either-or” type of behavioral preferences, some of which may have physical and mental health consequences.

It is as yet unclear to what extent hemisity traits contribute to the overall personality. This may be difficult to analyze. For example, although many RPs find it difficult to keep quiet, there was a small group of LPs who were very verbose. Similarly, it appears that some physically fearless RPs have social anxieties while many socially adept LPs have anxieties about physical danger. Further research is needed to explore the relationship between hemisity and overall personality, as conceptualized in the Big Five personality theory. Given the observed associations, it is hypothesized that right hemisity will be positively correlated with extraversion and openness to experience, whereas left hemisity is hypothesized to be positively correlated with conscientiousness and negatively correlated with openness to experience.

Perhaps even more difficult will be uncovering the underlying brain basis for these differences. The demonstration of the existence of hemisity opens the doors of explanation beyond sex-gender based personality ideas for many presently confusing characteristic human attitudes and human relations outcomes.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Honolulu Kaiser Permanente Medical Program for use of their MRI facility. We are also indebted to our healthy subjects from the University of Hawaii community who volunteered for this unfunded research.

References

Adan, A., and Almirall, H. (1992). The influence of age, work schedule and personality on morningness dimension. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 12, 95–99.

Bagby, R. M., Parker, J. D. A., and Taylor, G. J. (1994). The twenty-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale-I. item selection and cross-validation of the factor structure. J. Psychosom. Res. 38, 23–32.

Beaumont, G., Young, A., and McManus, C. (1984). Hemisphericity: a critical review. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 1, 190–212.

Bogen, J. E. (1969). The other side of the brain. II. An appositional mind. Bull. Los Angel. Neuro. Soc. 34, 135–162.

Brownell, H. H., Simpson, T. L., Bihrle, A. M., Potter, H. H., and Gardner, H. (1990). Appreciation of metaphoric alternative word meanings by left and right brain damaged patients. Neuropsychologia 28, 375–383.

Buchanan, D. C., Waterhouse, G. J., and West, S. C. Jr. (1980). A proposed neurophysiological basis of alexithymia. Psychother. Psychosom. 34, 248–255.

Cassano, G. B., Mula, M., Rucci, P., Miniati, M., Frank, E., Kupfer, D. J., et al. (2009). The structure of lifetime manic–hypomanic spectrum. J. Affect. Disord. 112, 59–70.

Channon, S., Pellijef, A., and Rule, A. (2005). Social cognition after head injury: sarcasm and theory of mind. Brain Lang. 93, 123–134.

Christman, S. (1995). “Independence versus integration of right and left hemisphere processing: effects of handedness,” in Hemispheric Communication: Mechanisms and Models, ed F. L. Kitterle (Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum), 231–254.

Davidson, R. J. (1984). “Affect, cognition, and hemispheric specializtion,” in Emotions, Cognitions and Behavior, eds C. E. Izard, J. Kagan, and R. E. Zajonc (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press), 320–365.

Fassler, O., Knox, J., and Lynn, S. J. (2006). The Iowa sleep experiences survey: hypnotizability, absorption, and dissociation. Pers. Individ. Dif. 41, 675–684.

Golden, R. R., and Meehl, P. E. (1979). Detection of the schizoid taxon with MMPI indicators. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 88, 217–233.

Happé, F., Brownell, H., and Winner, E. (1999). Acquired ‘theory of mind’ impairments following stroke. Cognition 70, 211–240.

Hoppe, K. D., and Bogen, J. E. (1977). Alexithymia in twelve commissurotomized patients. Psychother. Psychosom. 28, 148–155.

Horne, J. A., and Ostberg, O. (1976). A self-assessment questionnaire to determine morningness- eveningness in human circadian rhythms. Int. J. Chronobiol. 4, 97–110.

Igarashi, T., Komaki, G., Lane, R. D., Moriguchi, Y., Nishimura, H., Arakawa, M., et al. (2011). The reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the levels of emotional awareness scale (LEAS-J). Biopsychosoc. Med. 5, 2.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 10, 144–158.

Langdon, R., Coltheart, M., Ward, P. B., and Catts, S. V. (2002). Disturbed communication in schizophrenia: the role of poor pragmatics and poor mind-reading. Psychol. Med. 32, 1273–1284.

Lieberman, M. D., and Rosenthal, R. (2001). Why introverts can't always tell who likes them: multitasking and nonverbal decoding. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 80, 294–310.

Ludvigh, E. J. 3rd, and Happ, D. (1974). Extraversion and preferred level of sensory stimulation. Br. J. Psychol. 65, 359–365.

Malinowski, P. (2008). Mindfulness as psychological dimension: concepts and applications. Ir. J. Psychol. 29, 155–166.

Mathew, R. J., Weinman, M. L., and Barr, D. L. (1984). Personality and regional cerebral blood flow. Br. J. Psychiatry 144, 529–532.

Mohr, C., Rowe, A. C., and Crawford, M. T. (2008). Hemispheric differences in the processing of attachment words. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 30, 471–480.

Montgomery, W. A., and Jones, G. E. (1984). Laterality, emotionality, and heartbeat perception. Psychophysiology 21, 459–465.

Morton, B. E. (2001). Large individual differences in minor ear output during dichotic listening. Brain Cogn. 45, 229–237.

Morton, B. E. (2002). Outcomes of hemisphericity questionnaires correlate with unilateral dichotic deafness. Brain Cogn. 49, 63–72.

Morton, B. E. (2003a). Phased mirror tracing outcomes correlate with several hemisphericity measures. Brain Cogn. 51, 294–304.

Morton, B. E. (2003b). Two-hand line-bisection task outcomes correlate with several measures of hemisphericity. Brain Cogn. 51, 305–316.

Morton, B. E. (2003c). Asymmetry questionnaire outcomes correlate with several hemisphericity measures. Brain Cogn. 51, 372–374.

Morton, B. E. (2003d). Line bisection-based hemisphericity estimates of university students and professionals: evidence of sorting during higher education and career selection. Brain Cogn. 52, 319–325.

Morton, B. E. (2011). Neuroreality: A Scientific Religion to Restore Meaning, or How 7 Brain Elements Create 7 Minds and 7 Realities. Doral, FL: Megalith Books. (amazon.com).

Morton, B. E. (2012). Two Human Species Exist: Their Hybrids are Dyslexics, Homosexuals, Pedophiles, and Schizophrenics. Doral, FL: Megalith Books. (amazon.com).

Morton, B. E., and Rafto, S. E. (2006). Corpus callosum size is linked to dichotic deafness and hemisphericity, not sex or handedness. Brain Cogn. 62, 1–8.

Morton, B. E., and Rafto, S. E. (2010). Behavioral laterality advance: neuroanatomical evidence for the existence of hemisity. Pers. Individ. Dif. 49, 34–42.

Muro, A., Goma-i-Freixanet, M., and Adan, A. (2009). Morningness-eveningness, sex, and the Alternative Five Factor Model of personality. Chronobiol. Int. 26, 1235–1248.

Premack, D., and Woodruff, G. (1978). Chimpanzee problem-solving: a test for comprehension. Science 202, 532–535.

Prifitera, A. (1981). Jungian personality correlates of cerebral hemispheric preference. J. Anal. Psychol. 26, 151–162.

Richardson, A. (1977). Verbalizer-visualizer: a cognitive style dimension. J. Ment. Imagery 1, 119–126.

Richardson, A. (1978). Subject, task, and tester variables associated with initial eye movement responses. J. Ment. Imagery 2, 85–100.

Schwartz, G. E. (1990). “Psychobiology of repression and health: a systems approach,” in Repression and Dissociation: Implications for Personality Theory, Psychopathlogy and Health, ed J. L. Singer (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press), 405–434.

Shamay-Tsoory, S. G., Tomer, R., and Aharon-Peretz, J. (2005). The neuroanatomical basis of understanding sarcasm and its relationship to social cognition. Neuropsychology 19, 288–300.

Sifneos, P. E., Apfel-Savitz, R., and Frankel, F. H. (1977). The phenomenon of alexithymia. Psychother. Psychosom. 28, 47–57.

Stuss, D. T., Gallup, G. G. Jr., and Alexander, M. P. (2001). The frontal lobes are necessary for ‘theory of mind’. Brain 124, 279–286.

Tellegen, A., and Atkinson, G. (1974). Openness to absorbing and self-altering experiences (‘absorption’), a trait related to hypnotic susceptibility. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 83, 268–277.

Thalbourne, M. A., Bartemucci, L., Delin, P. S., Fox, B., and Nofi, O. (1997). Transliminality: its nature and correlates. J. Am. Soc. Psych. Res. 91, 305–331.

Tomarken, A. J., and Davidson, R. J. (1994). Frontal brain activation in repressors and nonrepressors. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 103, 339–349.

van de Ven, V., and Merckelbach, H. (2003). The role of schizotypy, mental imagery, and fantasy proneness in hallucinatory reports of undergraduate students. Pers. Individ. Dif. 35, 889–896.

Waldinger, M. D., and Van Strien, J. W. (1995). Repression and cerebral laterality: a study of selective hemispheric activations. Neuropsychiatry. Neuropsychol. Behav. Neurol. 9, 1–5.

Zenhausern, R. (1978). Imagery, cerebral dominance, and style of thinking: a unified field model. Bull. Psychon. Soc. 21, 381–384.

Appendix 1

A Binary Preference Questionnaire

Bruce E. Morton, Ph.D., University of Hawaii School of Medicine

Your Name or Number: ______________, Sex, M or F___, Handedness, R or L__, Parental Ethnicity____________.

For each pair of statements, mark an X by the viewpoint that is most like your own.

Appendix 2

Hemisity Questionnaire

Bruce E. Morton, Ph.D., University of Hawaii School of Medicine

Name or I.D. Number________________. Sex___, Age___, Handedness___, Ethnicity of your Mother's family____________, Ethnicity of your Father's family______________.

Keywords: brain behavioral laterality, executive asymmetry, hemisity and personality, hemisty and gender

Citation: Morton BE (2012) Left and right brain-oriented hemisity subjects show opposite behavioral preferences. Front. Physio. 3:407. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00407

Received: 23 July 2012; Accepted: 02 October 2012;

Published online: 02 November 2012.

Edited by:

Eugene Nalivaiko, University of Newcastle, AustraliaReviewed by:

Robert Marvit, Rehab Hospital of Pacific, USAJamie Jensen, Brigham Young University, USA

Copyright © 2012 Morton. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in other forums, provided the original authors and source are credited and subject to any copyright notices concerning any third-party graphics etc.

*Correspondence: Bruce E. Morton, JABSOM Guatemala Office, 19-48 5th Ave., Unit 3N, Zone 14, Guatemala City, Guatemala. e-mail: bemorton@hawaii.edu