- Institute of Life Sciences, Jiangsu University, Zhenjiang, China

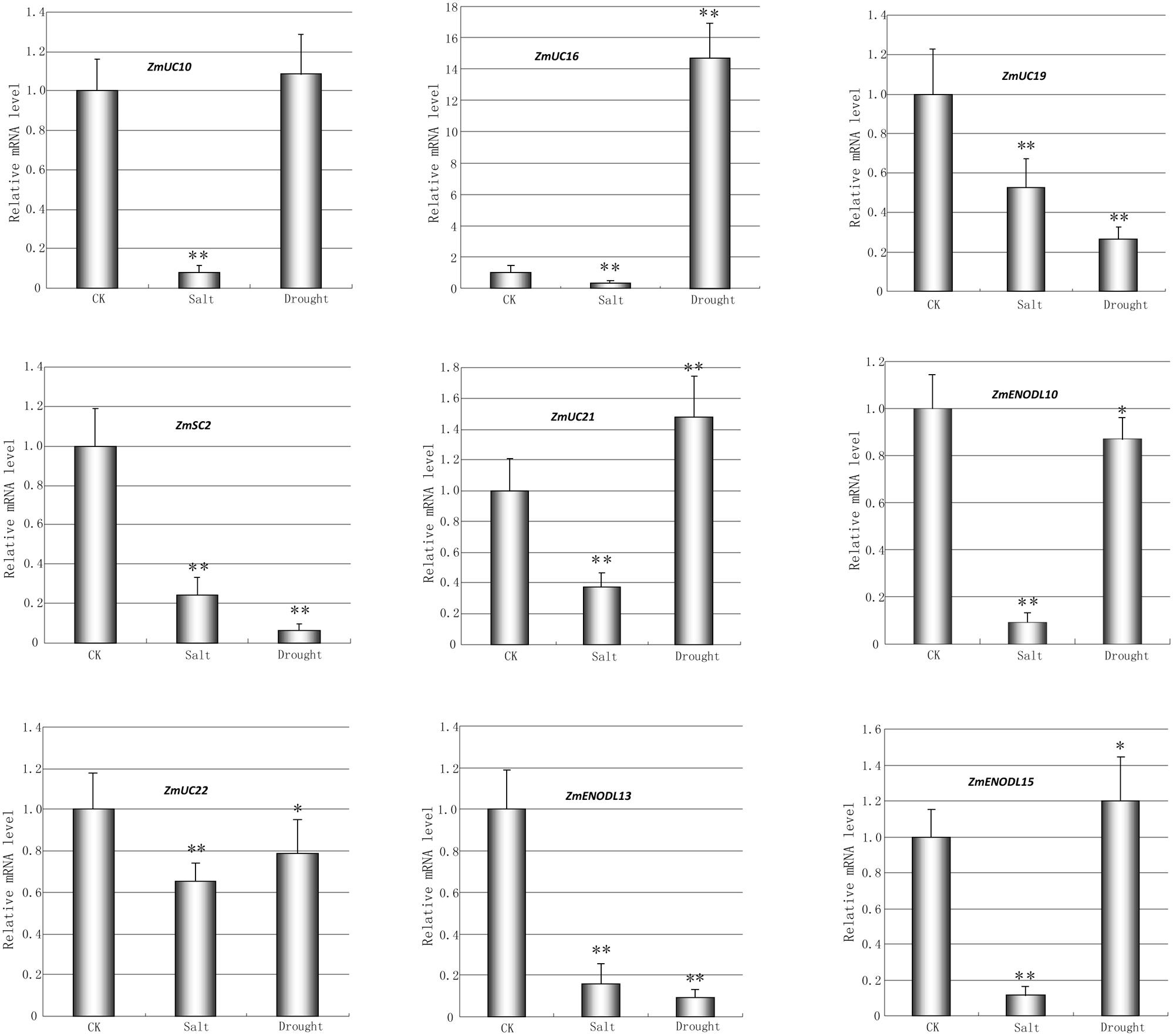

Phytocyanins (PCs) are plant-specific blue copper proteins, which play essential roles in electron transport. While the origin and expansion of this gene family is not well-investigated in plants. Here, we investigated their evolution by undertaking a genome-wide identification and comparison in 10 plants: Arabidopsis, rice, poplar, tomato, soybean, grape, maize, Selaginella moellendorffii, Physcomitrella patens, and Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. We found an expansion process of this gene family in evolution. Except PCs in Arabidopsis and rice, which have described in previous researches, a structural analysis of PCs in other eight plants indicated that 292 PCs contained N-terminal secretion signals and 217 PCs were expected to have glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchor signals. Moreover, 281 PCs had putative arabinogalactan glycomodules and might be AGPs. Chromosomal distribution and duplication patterns indicated that tandem and segmental duplication played dominant roles for the expansion of PC genes. In addition, gene organization and motif compositions are highly conserved in each clade. Furthermore, expression profiles of maize PC genes revealed diversity in various stages of development. Moreover, all nine detected maize PC genes (ZmUC10, ZmUC16, ZmUC19, ZmSC2, ZmUC21, ZmENODL10, ZmUC22, ZmENODL13, and ZmENODL15) were down-regulated under salt treatment, and five PCs (ZmUC19, ZmSC2, ZmENODL10, ZmUC22, and ZmENODL13) were down-regulated under drought treatment. ZmUC16 was strongly expressed after drought treatment. This study will provide a basis for future understanding the characterization of this family.

Introduction

Blue copper proteins are ancient, type-I copper-containing proteins, which function as electron transporters in bacteria and plants (Giri et al., 2004). Blue copper proteins in plant are defined as phytocyanins (PCs), which include plastocyanins and some phytocyanin-related proteins (De Rienzo et al., 2000). Structurally, PCs consist of two conserved disulfide bridged Cys residues, four copper ligands, and an eight-stranded β-sandwich fold (Hart et al., 1996). According to the glycosylation state, copper ligand residues, domain organization, and spectroscopic properties of proteins, PCs can be divided into four groups: plantacyanins (PLCs), uclacyanins (UCs), stellacyanins (SCs), and early nodulin-like proteins (ENODLs; Nersissian et al., 1998; Ma et al., 2011; Li et al., 2013). PLCs contain a copper binding site consisting of one Met, one Cys, and two His ligands (Guss et al., 1996). And the N-terminal leader sequences in PLCs usually contain the endoplasmic reticulum target signal peptides (Nersissian et al., 1998). Although UCs also include the same four residues as described above in their copper-binding sites, they contain another domain resembling a cell-wall structural proteins (glycoproteins; Nersissian et al., 1998). SCs use a Gln residue as a copper ligand, while PLCs and UCs have a Met residue in this position (Nersissian et al., 1998). Like UCs, SCs consist of a copper-binding domain and a glycoprotein-like domain. The structure of ENODLs is similar to that of UCs and SCs, but ENODLs cannot bind copper, which might be involved in process without copper-binding (Greene et al., 1998; Mashiguchi et al., 2009; Ma et al., 2011).

Previous studies have indicated that PCs are involved in various plant activities, including cell differentiation and reorganization (Fedorova et al., 2002; Kato et al., 2002), pollen tube germinating and anther pollination (Kim et al., 2003; Dong et al., 2005), reproductive potential determining (Khan et al., 2007), apical buds organ development (Mashiguchi et al., 2009), and somatic embryogenesis (Poon et al., 2012), etc. In addition, PCs may also function in stress responses, including enhancing osmotic tolerance (Wu et al., 2011), inhibiting aluminum absorption and protecting cell from aluminum toxicity (Ezaki et al., 2001, 2005). Several researches have indicated that salt and drought stresses can induce the expression of some PC genes, suggesting the potential response to abiotic stresses (Ozturk et al., 2002; Ma et al., 2011).

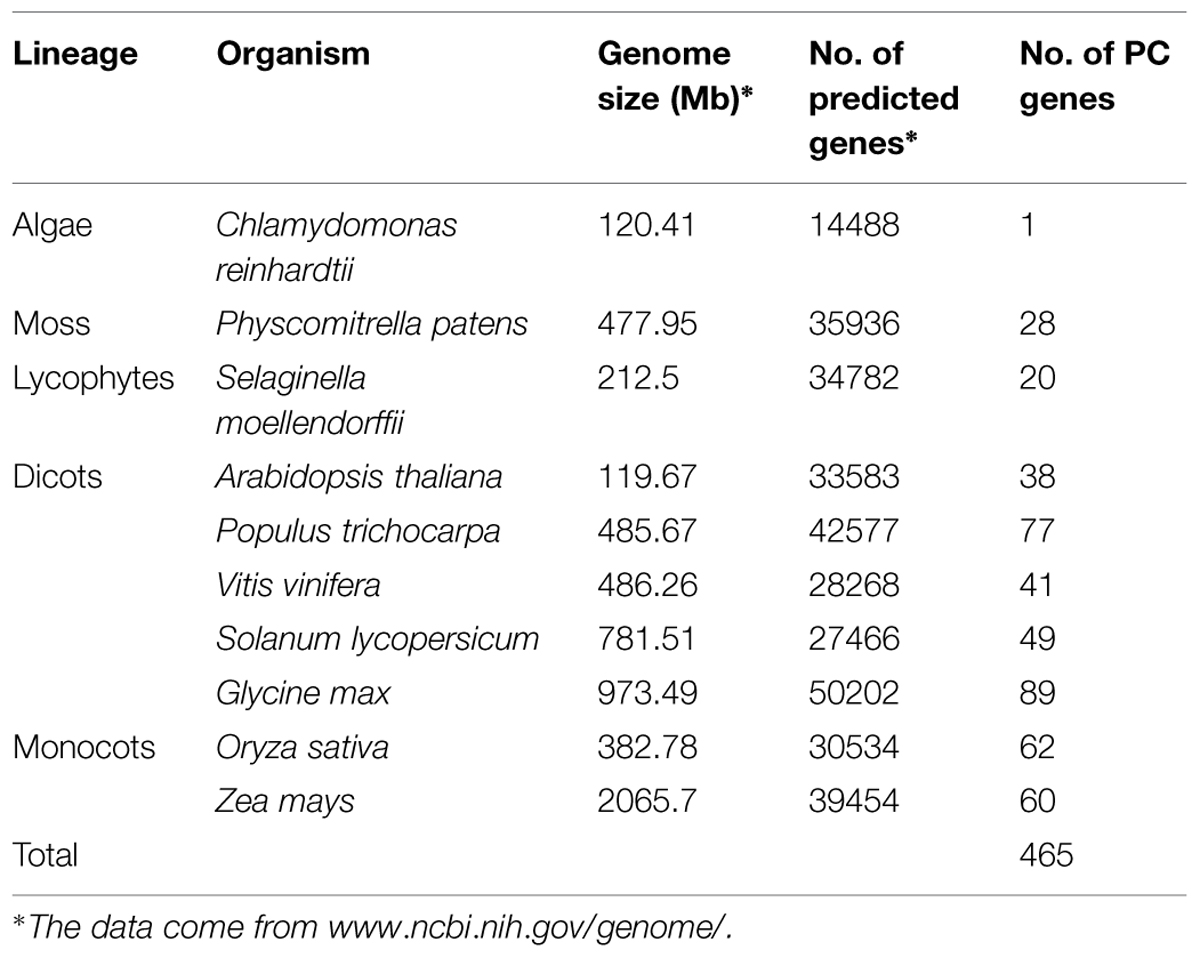

To date, through a comprehensive bioinformatics analysis, only 38, 62, and 84 PC genes have been identified in Arabidopsis, rice and Brassica rapa, respectively (Mashiguchi et al., 2009; Showalter et al., 2010; Ma et al., 2011; Li et al., 2013). In the present study, including Arabidopsis and rice, we identified the PC gene family of 10 species in plants, and each species contains 1–89 PC genes. Considering the important roles associated with developmental functions and stress responses, and the number of the PC genes varied largely among plant species, it’s of considerable interest to us to research how the PC genes have evolved in Plantae, and how and why different plant species have obtained such different PC genes. Here, our results indicate that the PC gene family has an expansion process in plant evolution, and that tandem and segmental duplications and retrotransposition play dominant roles for their expansion. Our studies also reveal diverse expression patterns of the PC genes in maize.

Materials and Methods

Identification of the PC Genes Plants and Bioinformatics Analysis

We first used Arabidopsis, rice and B. rapa PC sequences (Mashiguchi et al., 2009; Showalter et al., 2010; Ma et al., 2011; Li et al., 2013) as queries in basic local alignment search tool (BLAST) searches against the phytozome1 (Goodstein et al., 2012) with -1 expect (E) threshold to identify potential members of the PC gene family in plants. The sequences were then confirmed as encoding PC for the presence of a plastocyanin-like domain (PCLD) signature by the Pfam (Punta et al., 2012) searches. Subsequently, SignalP 4.1 Server (Petersen et al., 2011) was used to check the signal peptide (SP) of all proteins. Big-PI Plant Predictor (Eisenhaber et al., 2003) was used to predict the glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchor signal. In addition, we also used NetNGlyc 1.0 Server2 to predict the N-glycosylation sites in PC proteins. Putative arabinogalactan (AG) glycomodules were predicted mainly following the previously described criteria (Schultz et al., 2002; Showalter et al., 2010; Ma et al., 2011). The structure characteristics of PCs are shown in Supplementary Table S1.

Phylogenetic Analyses of the PC Gene Family in Plants

We used MUSCLE 3.52 (Edgar, 2004) to perform multiple sequence alignments of full-length protein sequences. And neighbor-joining (NJ) method in MEGA v5 (Tamura et al., 2011) was used to carry out phylogenetic analyses of the PC proteins with Dayhoff methods and default assumptions. Bootstrap analyses with 1,000 replicates were used to test support.

Estimation of the Maximum Number of Gained and Lost PCS

Next, we divided the phylogeny into different clades to determine the expansion extent of PC gene family in different plant lineages. Nodes among lineages denoted the most recent common ancestor (MRCA) and were labeled as V: Viridiplantae; E: Embryophyte; T: Tracheophyte; A: Angiosperm; G: Grass; Eu: eudicots; R: Rosid. Notung v2.6 (Chen et al., 2000) was used to infer gene loss and duplication events.

Conserved Motifs Analyses

MEME program3 (Bailey et al., 2006) was used to identify motifs in the plant PC proteins. This program was run with the following parameters: maximum number of motifs = 8, number of repetitions = any, and with optimum motif widths between 6 and 50 residues.

Chromosomal Location and Exon–Intron Structure Analysis

We used the annotation information of the PC genes on phytozome1 (Goodstein et al., 2012) to determine their chromosomal locations. The segmental duplication (or syntenic) regions of the different chromosomes in maize and Arabidopsis genomes were calculated with the Synteny Mapping and Analysis Program (SyMap; Soderlund et al., 2011). Genomicus4 online tool (Louis et al., 2013) was used to explore the PC gene organization information within and between genomes. The exon–intron structure of PC genes was also collected from genome annotations.

Estimating the Age of Duplicated Paralog Gene Pairs

We first determined paralogous gene pairs by the protein phylogeny, and used them as references for a multiple alignment of DNA coding sequences using embedded ClustalW (codons) software in MEGA v5 (Tamura et al., 2011). And we used K-Estimator 6.0 program (Comeron, 1999) to estimate the Ka and Ks values of paralogous genes. The approximate data of the duplication event for each of gene pair was calculated using the formula (T = Ks/2λ), assuming the clock-like rate (λ) is 1.5 × 10-8 and 6.5 × 10-9 synonymous/substitution site/year for Arabidopsis (Koch et al., 2000) and for maize (Gaut et al., 1996), respectively.

Microarray-Based Expression Analysis

We used the Plant Expression Database (PLEXdb; Dash et al., 2012) for expression analyses of maize PC genes. One experiment (ZM37) contributed by Kaeppler group in Sekhon et al. (2011) was selected in this study. Expression data in 34 selected tissues were gene-wise normalized in the Genesis (v 1.7.6) program (Sturn et al., 2002).

Plant Materials and Treatment

We used 1-week-old maize (Zea mays L. inbred line B73) seedlings to examine the expression patterns of PC genes under salt and drought stresses. Plants were grown in a plant growth chamber at 23 ± 1°C with a 14 h light/10 h dark photoperiod. Control (CK) seedlings were grown with normal irrigation. For salt treatment, the maize seedlings were kept in 150 mM NaCl for 24 h. For drought treatment, the seedlings were dried between folds of tissue paper at 23 ± 1°C for 3 h. Each sample was conducted three replicates.

RNA Isolation and Quantitative Real-Time PCR (QRT-PCR) Analysis

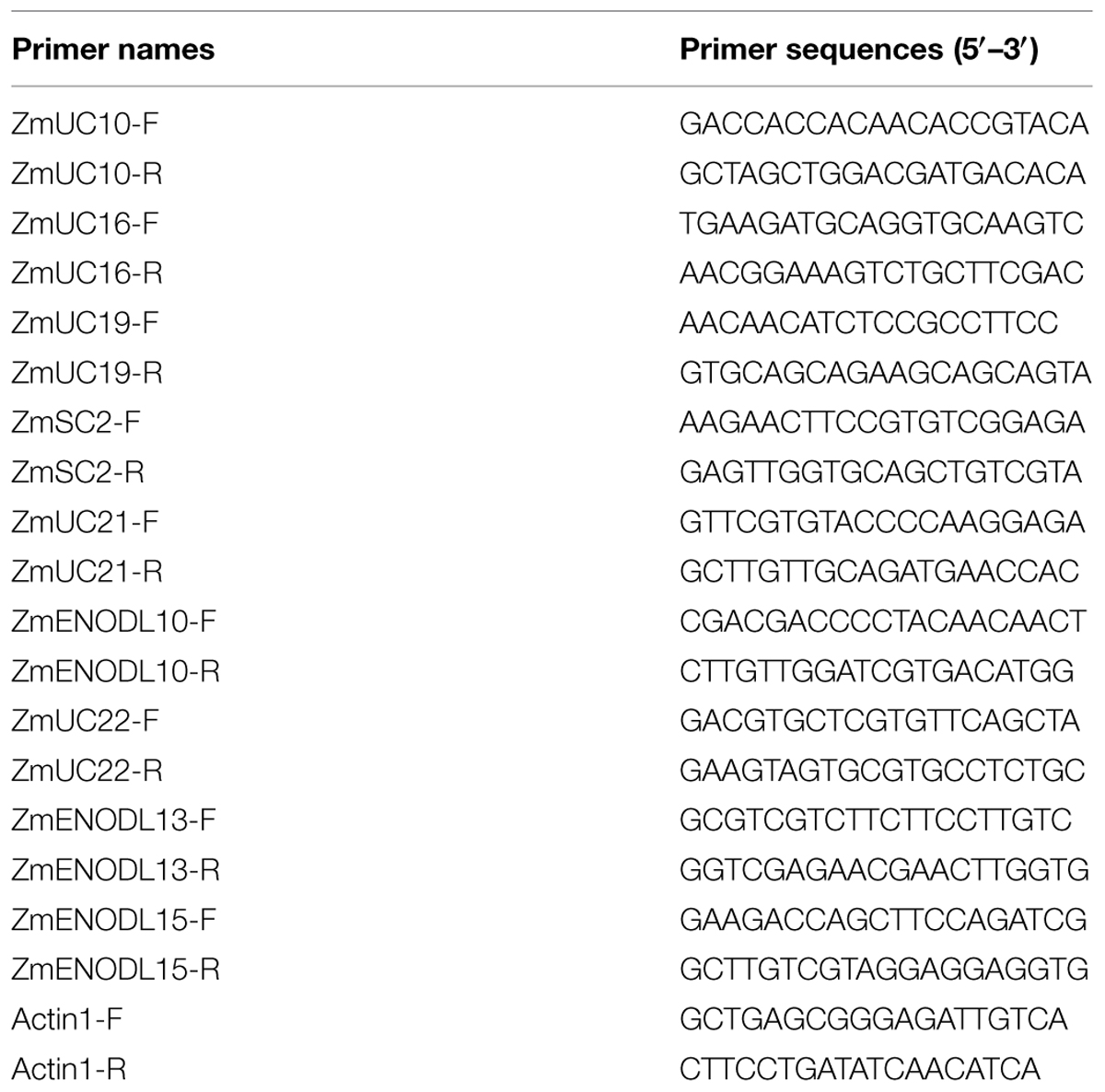

Trizol total RNA extraction kit (Sangon, Shanghai, China) was used to extract total RNA. Next, moloney murine leukemia virus (M-MLV) reverse transcriptase (TakaRa, Dalian, China) was used to perform reverse transcription. Triplicate quantitative assays were performed using SYBR Green Master Mix (TakaRa) with an ABI 7500 sequence detection system. Nine maize PC genes were randomly selected for real-time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis. The gene-specific primers (Table 3) were synthesized in Sangon. The expression level of Actin 1 (GRMZM2G126010) gene was used as a reference. 2-ΔΔCT method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001) was used to calculate the relative expression level of the PC genes.

Results and Discussion

Identification of PC Multigene Family in Plants

Phytocyanins are plant-specific ancient blue copper proteins which function as electron transporter. Though some researches (Mashiguchi et al., 2009; Showalter et al., 2010; Ma et al., 2011; Li et al., 2013) have been made in the characterization of plant PCs during the past decade, studies on this gene family are still scarce. In order to identify PC multigene families in other plant species, we used Arabidopsis, rice and B. rapa PC proteins as queries to perform a genome-wide search in eight genomes in Viridiplantae. The returned sequences were further confirmed as encoding PC by the Pfam (Punta et al., 2012) searches for the presence of a plastocyanin-like domain (PCLD) signature conserved in other PC proteins. As we know, the Arabidopsis and rice PCs have been bioinformatically and systematically studied in previous study (Ma et al., 2011; Li et al., 2013), so, the previous published data were also used to carry out deeper analysis. As a result, a total of 465 PC genes were identified from 10 plants in the phytozome database (Table 1). Our analysis shows that the number of PC genes ranged from 1 to 89 across the different plant species (Table 1). The soybean genome contains a maximum of 89 PC genes, while, chlamydomonas has only one. About 60 and 77 putative PC genes were identified from maize and poplar, respectively. Poplar has about two times PC genes than Arabidopsis, whereas rice and maize have a similar number of the PC genes when compared with that of poplar. By searching the Genome database of NCBI5, we found that the poplar, Arabidopsis and maize genomes contain 42,577, 33,583, and 39,454 genes, respectively, which are 39.4, 9.9, and 29.2% larger than that of rice (30,534), respectively. This implied that the number of PCs is not proportional to the size of the genomes. Obviously, there will be some forces to prompt the number change of this gene family in different plant species.

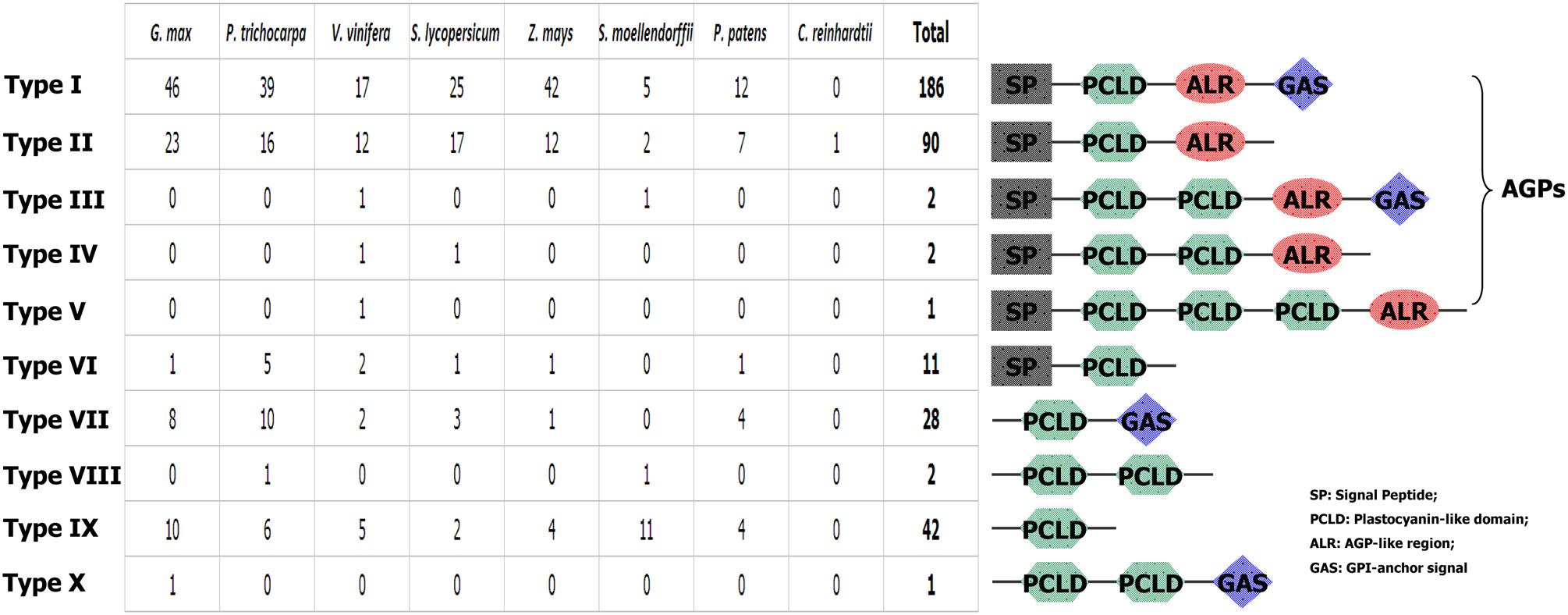

Structural Analysis of the Putative PC Proteins

To further investigate the structural characteristics of PC proteins, we used several bioinformatics websites as described in the materials and methods section to predict the AG glycomodules, SPs, GPI-anchor signals (GASs), and N-glycosylation sites of PCs. Our results (Supplementary Table S1) indicated that 292 PCs were predicted to contain an N-terminal SP required for targeting to the endoplasmic reticulum. In addition, 217 PCs were expected to have GASs responsible for plasma membrane localization. The subcellular localizations of plant PCs have been found to correlate with their specific functions. For example, AtSC3/AtBCB, an Arabidopsis blue copper binding protein, was strongly localized in the plasma membrane and induced by aluminum stress and oxidative stress, suggesting that the plant PCs may participate in some abiotic stress responses (Ezaki et al., 2001, 2005). Additionally, PC proteins accumulated in the sieve element plasma membrane may be involved in determining reproductive potential (Khan et al., 2007). Moreover, 281 PCs had putative AG glycomodules in the (Pro, Ala, Ser, Thr)-rich region. These 281 PCs might be AGPs for the existence of AG glycomodules and SPs. According to the distribution of the SP, PCLD, AGP-like region (ALR) and GAS, these PCs were separated into ten types (Figure 1). Type I PCs had typical properties, including an N-terminal SP, a PCLD, an ALR, and a C-terminal GAS. Type II PCs were short of GAS, while other features were similar to type I. Both GAS and ALR were absent from type VI, VIII, and IX PCs. Interestingly, we also found that type III, IV, VIII, and X PCs possessed two PCLDs, and type V had three PCLDs. The domain repeats are usually thought to evolve through recombination events and intragenic duplication (Björklund et al., 2006). The creation of new multi-domain architectures is an important mechanism that provides opportunities for the organism to expand its repertoire of cellular functions, such as transcriptional regulation, protein transport and assembly (Andrade et al., 2001; D’Andrea and Regan, 2003; Weiner et al., 2006). Furthermore, protein domain repeats may constitute a source of variability. In human genome, duplications are more common in genes containing repeated domains than in non-repeated ones (Björklund et al., 2010). The domain repetition is quite important in evolution, since it provides a path where proteins can evolve through removing or adding functionally similar or distinct blocks (Light et al., 2012). In this study, we identified some multi-PCLD domains in PCs. This presence of PCLD domain repeats contribute to the complexity of this gene family. Its effect on the function of PC proteins remains to be examined. However, our findings suggest that the PCLD repeats may play an important role in PC protein evolution.

FIGURE 1. Graphical representation of 10 types of PCs and their comparative analysis among the eight plant species.

Origin and Contrasting Changes in the Numbers of Plant PC Genes

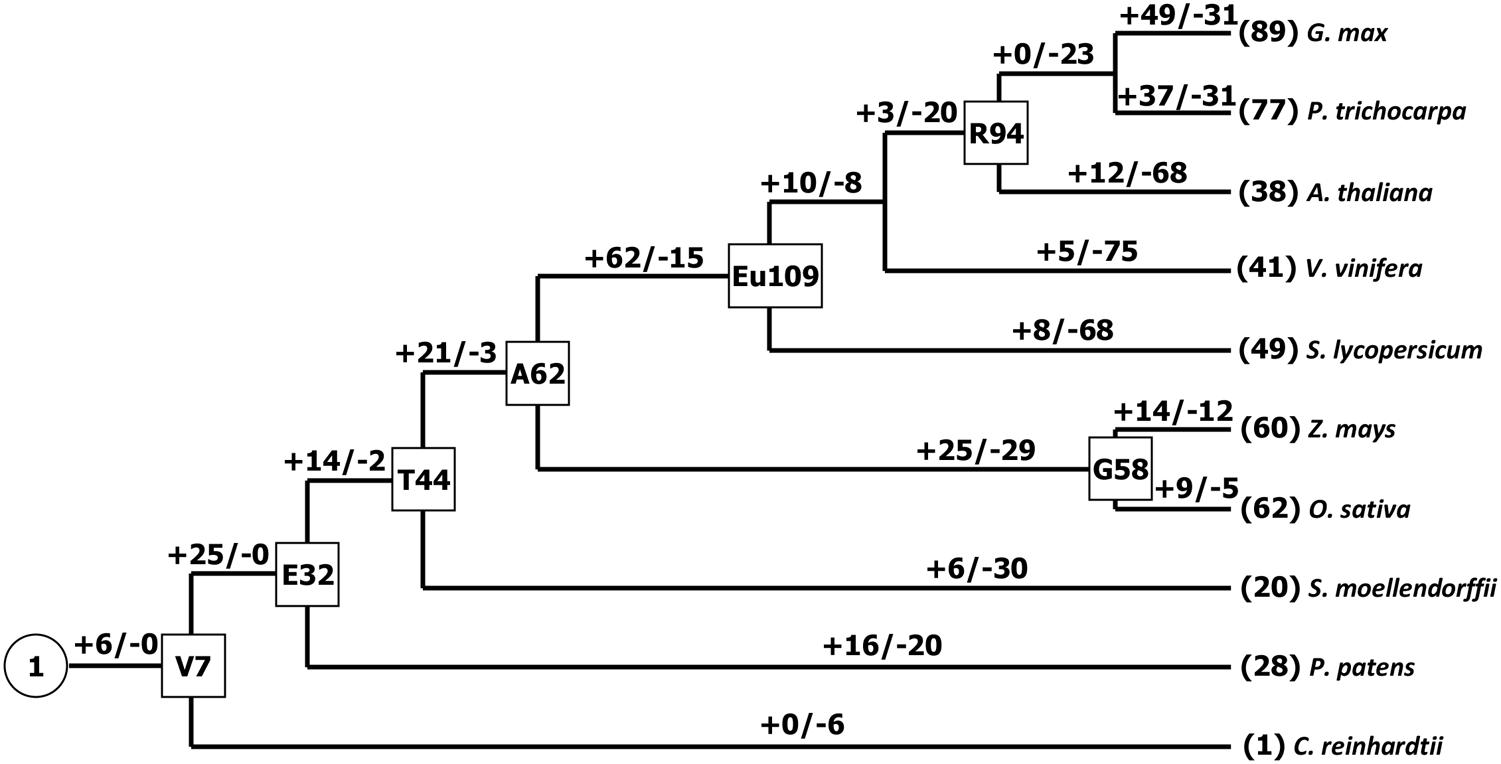

It has been suggested that the Chlorophycean is the primitive species in Viridiplantae from which all land plants have evolved (Misumi et al., 2008). The earliest PCs possibly originated about 1 billion years ago in algae (Merchant et al., 2007; Misumi et al., 2008). Our search for PCs in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii found only one member. Therefore, the origin of the plant PC genes could be traced to the ancient algae. The PC gene family appeared to expand by duplication events. For example, Physcomitrella patens has 28 PC genes, which soybean exhibites 89 paralogous gene sequences representing about 19% of total 465 identified PCs, which might be due to at least three whole genome duplications (Schmutz et al., 2010). As we know, expansion and conservation of a gene family in evolution imply important roles during organism adaptation to environment (Cao et al., 2011; Cao and Shi, 2012). Next, we also estimated the number of PC genes in the MRCA to better understand how this family gene has evolved in Viridiplantae. Reconciliation of the species phylogeny with the gene trees suggested that one ancestral PC gene exist in the MRCA of Viridiplantae. Furthermore, we identified 32 orthologous genes in the Embryophyte MRCA and 44 in the MRCA of Tracheophyte (Figure 2). We also found that the number of PCs remained relatively increased from the land plants (P. patens) to the angiosperms. Eudicot ancestral PCs once more expanded significantly after the separation from monocot species about 145 million years ago (Xu et al., 2009). We identified about 109 ancestral PC genes in the MRCA of eudicots. After that, many PC genes have lost in the eudicots. It appeared that the PC family had been reduced in all the analyzed eudicot species compared with the number of MRCA in eudicots. For example, the number of PCs decreased approximately 65.1 and 55 percent for Arabidopsis and tomato, respectively. Whereas when compared the number of ancestral PC genes, it appeared that this family had expanded in all the extant species. In addition, this expansion was uneven among these plant species. For instance, there are 77, 60, 41, and 28 genes in poplar, maize, grape, moss, respectively, while the estimated numbers of genes in the MACA of Viridiplantae are seven. Therefore, poplar, maize, grape and moss have gained 70, 53, 34 and 21 genes, respectively, since their splits. The numbers of genes gained in the soybean lineage are much greater than that in other lineages.

FIGURE 2. Gain and loss of the PC genes in plant evolution. Seven internal nodes (V, Viridiplantae; E, Embryophyte; T, Tracheophyte; A, Angiosperm; G, Grass; Eu, eudicots; R, Rosid) are shown in the rectangles. Plus and minus signs indicate gene gain and loss events, respectively.

Chromosomal Distribution and Duplication Patterns of PC Genes in Plants

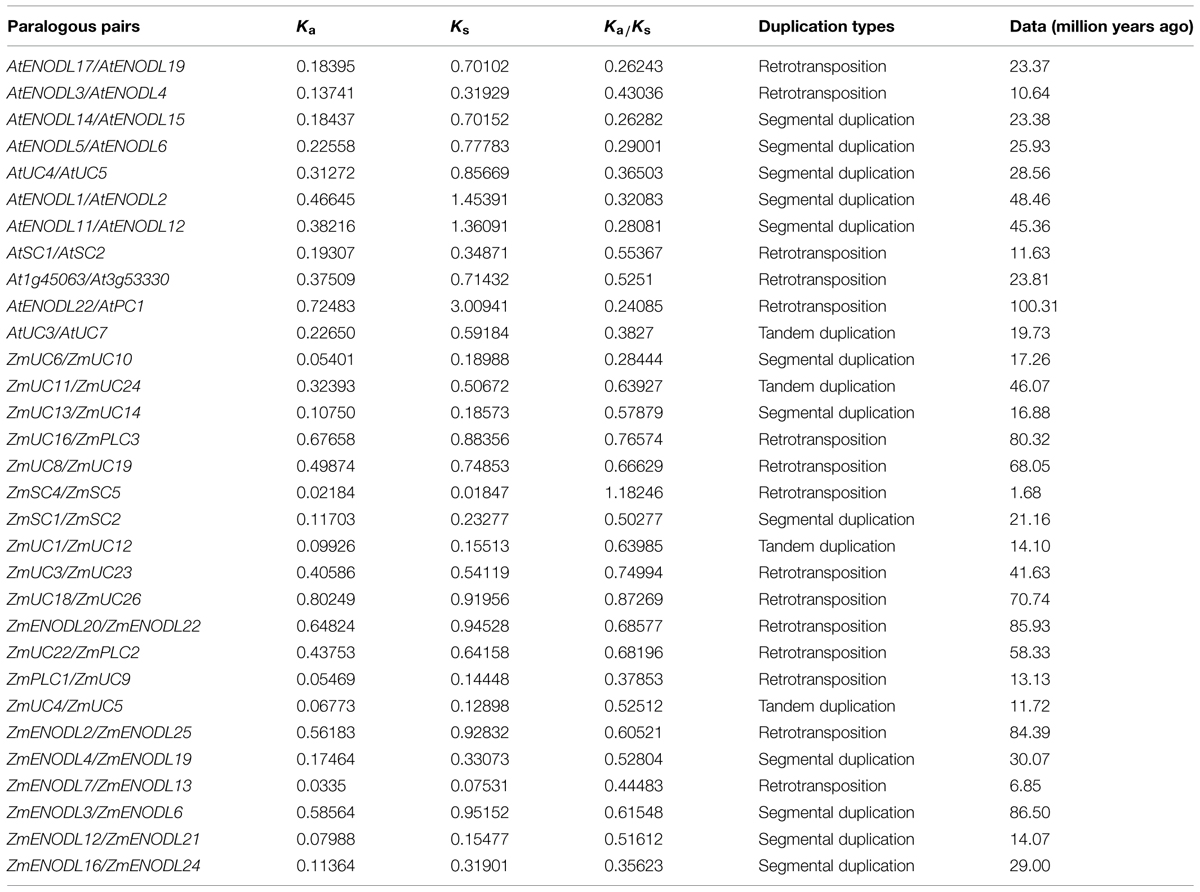

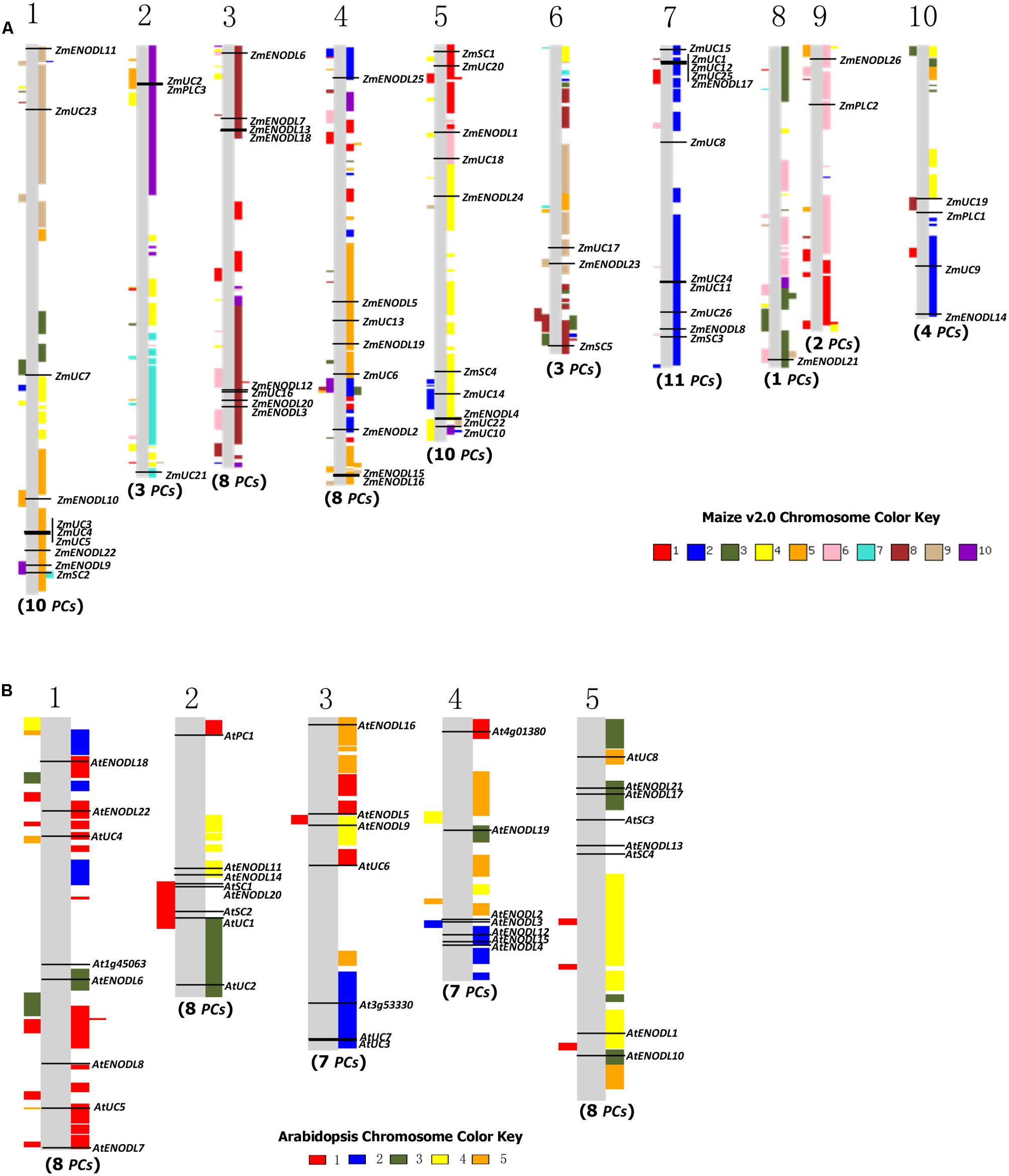

Gene duplication, which usually occurs via segmental duplication, tandem duplication and retrotransposition, plays important roles in organismal evolution (Chen et al., 2014; Cao and Li, 2015). To search for duplication mechanisms for PC genes, as examples, we examined their genomic distribution in Arabidopsis and maize. The results showed that PC genes are dispersed throughout Arabidopsis and maize genomes (Figure 3). We also found that about 79.5 and 96.7% of PC genes locate on the duplicated segments of chromosomes in Arabidopsis and maize, respectively. Within identified duplication events, 5 of 11 pairs (AtENDOL14/AtENODL15, AtENODL5/AtENODL6, AtUC4/AtUC5, AtENODL1/AtENODL2, and AtENODL11/AtENODL12) in Arabidopsis and 7 of 20 pairs (ZmUC6/ZmUC10, ZmUC13/ZmUC14, ZmSC1/ZmSC2, ZmUC22/ZmPLC2, ZmENODL4/ZmENODL19, ZmENODL12/ZmENODL21, ZmENODL16/ZmENODL24) in maize are retained (Figure 3). In addition, evolutionary dates of these duplicated PC genes were also estimated (Table 2). The result indicated that duplication events for Arabidopsis six pairs and maize seven pairs occurred within the past 19.73–28.58 million years and 11.72–21.16 million years, respectively (Table 2). These periods coincide with the time of the secondary large-scale genome duplication in Arabidopsis and maize (Gaut et al., 1996; Koch et al., 2000). In addition, we also observed some earlier segmental duplication events occurred around from 41.63 to 58.33 MYA in the PCs of Arabidopsis (AtENODL1/AtENODL2 and AtENODL11/AtENODL12) and maize (ZmUC3/ZmUC23 and ZmUC22/ZmPLC2), nearly within or following grasses origination (Kellogg, 2001). Interestingly, we also found that about 31.67% of PC genes were tandemly clustered in maize, and only one clustered PCs (AtUC7-AtUC3) were also identified in Arabidopsis (Figure 3), suggesting that tandem duplication may be another factor generating the family genes. In a word, segmental duplication and tandem duplication contribute to the expansion of the PC gene family.

FIGURE 3. Gene locations and genomic duplication in maize (A) and Arabidopsis (B). SyMAP v3.4 (Soderlund et al., 2011) was used to depict the paralogous regions in the putative ancestral constituents of the maize (A) and Arabidopsis (B) genomes. Moreover, some relationship of orthologs or paralogs was confirmed with the Genomicus (http://www.dyogen.ens.fr/genomicus/) online tool (Louis et al., 2013). The segmental duplication regions are supposed to be colored with the same way to the relevant chromosome color. For example, the color key of maize chromosome 1 is red, which means that all red regions on the chromosomes are segmental duplicated from the chromosome 1. Using this method, we can get all of the paralogous regions among different chromosomes in the genome.

Similar expansion patterns were also found in Oryza sativa and B. rapa PC genes (Ma et al., 2011; Li et al., 2013). In the rice genome, 20 of 62 OsPC genes were segmental duplications; while, 63 of 84 BrPC genes were attributed to segmental duplications in the B. rapa. This indicated that this type of duplication event contributes to the expansion of the PC genes in these plants. Tandem duplication is an important factor dramatically expanding new copies in clusters by unequal recombination or replication slippage (Anderson and Roth, 1977; Blanc and Wolfe, 2004; Cannon et al., 2004; Thomas, 2005). Initially, tandem duplicated genes have similar sequences and functions; but, in the subsequent evolution, they tend to divergence in structure and expression patterns during too many changes in the cis- and trans-acting effects, DNA sequences, regulatory networks, and chromatin modifications (Charon et al., 2012). Several previous studies have investigated these divergences between duplicate genes (Makova and Li, 2003; Li et al., 2005; Ganko et al., 2007). During the process of evolution, some duplicated genes were maintained the similarity of functions, while others either gained new functions (neofunctionalization) or subdivided their functions (subfunctionalization), or lost them (pseudogenization; Pinyopich et al., 2003; Franzke et al., 2010; Wang and Paterson, 2011). Plants cannot freely escape the changing environment. Therefore, some genes associated with stress defense are required to expand to resist these environmental stimulations. Previous studies have indicated that tandem duplicated genes are often involved in responses to environmental stimuli or stress in plants (Leister, 2004; Maere et al., 2005; Fang et al., 2012). Our results also indicated that about 31.67 and 29.03% of PC genes were tandemly clustered in monocots maize and rice, respectively. And some stress responses were often associated with the PC proteins (Ezaki et al., 2001, 2005; Ozturk et al., 2002; Ma et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2011). Amplification of the PC genes by tandem duplication in monocots maize and rice is regarded as a mechanism for protecting plants from harmful stresses, which may be crucial for organismal adaptation to different environments. Only one clustered PCs (AtUC7-AtUC3) were identified in Arabidopsis, and no duplicated PC genes were identified from tandem duplications in another eudicot B. rapa (Li et al., 2013), implying different expansion types of this gene family between monocots maize and rice and eudicots Arabidopsis and B. rapa.

We also found that the Ka/Ks values of the sequences among PC pairs were significantly different (Table 2). Moreover, except for the ZmSC4/ZmSC5 gene pairs, all other’s estimated Ka/Ks values were less than 1, implying that most of the duplicated PC sequences within these pairs are under purifying selection pressure in evolution. The Ka/Ks value of ZmSC4/ZmSC5 pairs is 1.18246, indicating that positive selection might be occurred between this gene pairs after duplication about 1.68 Mya. Gene or protein evolution is an outcome of the interplay between mutation and selection. During evolution, some functional regions have reached the optimal state. Therefore, most of the mutations that altered the function will be abandoned by purifying selection. With changes in environment, subsequent selective pressure spurs such regions to change to improve the fitness of the organism in a new environment accordingly. From this point, detecting positive selection seems especially necessary, because it can indicate selective advantages in changing the gene or protein sequences. These selective advantages are essential for understanding of functional regions of the gene or protein and functional shift (Morgan et al., 2010). In this study, one duplicated gene pairs (ZmSC4/ZmSC5) were identified to undergo positive selection after separated by duplication, implying that functional divergence of duplicated genes might have accelerated by positive selection during long periods of evolution. Thus, this might facilitate an adaption to different environments for the organism.

Motif Distribution and Intron Loss in Some Clades

We used Pfam (Punta et al., 2012) to identify the major domains of PC proteins in plants. Results showed that all PC proteins possessed PCLD signature that is essential for electron transport activity. To recognize some smaller individual motifs, we used the MEME6 (Bailey et al., 2006) to study the diversification of PC proteins in plants. As a result, we identified eight distinct motifs in these members (Supplementary Figure S1). Obviously, most members in each clade have similar motif compositions, suggesting functional conservation of the PC proteins in the same clade (Supplementary Figure S1). Therefore, motif compositions of the PC proteins in each clade may provide additional support for the phylogenetic analyses (Cao, 2012).

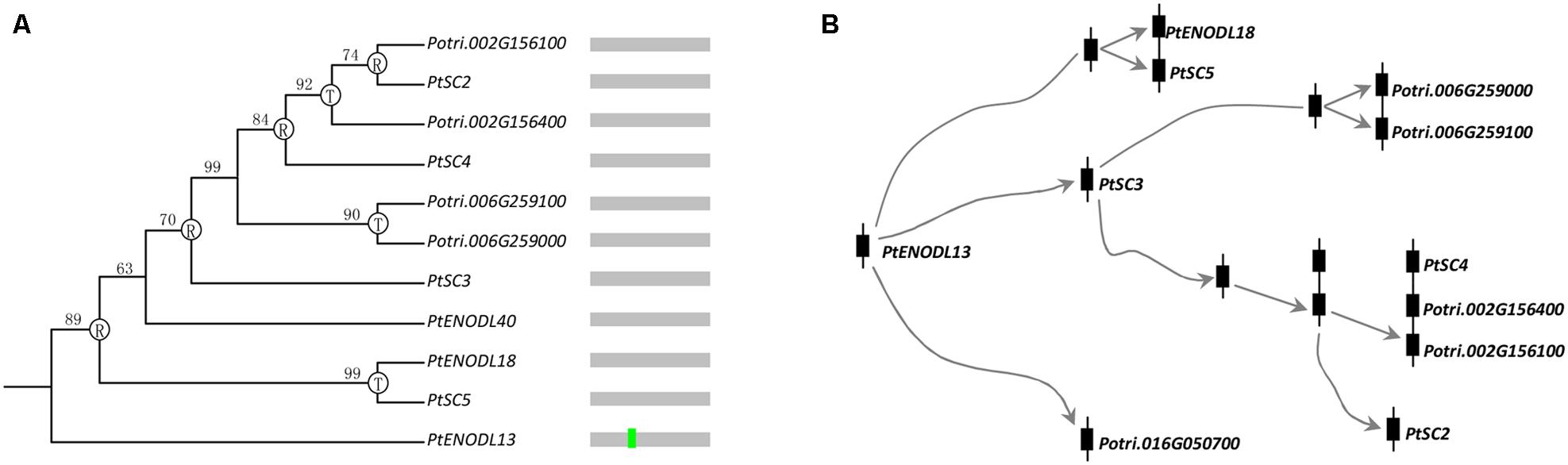

Exon–intron structure has been used to explain the evolutionary relationships (Cao et al., 2010; Koralewski and Krutovsky, 2011; Chen and Cao, 2014). Next, we compared the exon–intron organization of the PCs in 10 plants. Supplementary Figure S1 provided a detailed illustration of the position of introns of each PCLD domain. Our results indicated a conserved 1 phase intron insertion in PCLD of most PC paralogs. Interestingly, we also found that this intron insertion has been lost in some poplar PCLD (Supplementary Figure S1). Moreover, these intronless genes in PCLD tended to form species-specific clusters on the poplar chromosomes 2, 6, and 15 (Supplementary Figure S1). It may be the consequences of retroposition and tandem duplications. The loss of intron in these PCs was likely associated with recent evolutionary expansion, like, retroposition and tandem duplication. To test this hypothesis, we identified the candidate donor gene based on the following two criteria. The first criterion is that the retrogene will have identical sequences to the donor gene after retroposition, so they will cluster together in a phylogenetic tree (Kong et al., 2007). Since retrogene comes from retroposition, it usually lacks specific introns compared with the donor gene. Therefore, the second criterion is that the donor gene can be judged from the presence/absence of the specific intron (Kong et al., 2007). Figure 4 shows an example of intron loss caused by gene expansion. Genes with the conserved intron (such as, PtENODL13) usually locate basal positions of the phylogenetic tree, while genes without the intron (such as, others 10 PCs in the clade as shown in Figure 4) often form terminal clades. It is likely that PtENODL13 contains the conserved intron and is their ancestor (donor gene), from which the intronless retrogenes were generated by retroposition and tandem duplication.

FIGURE 4. Evolution of one PC clade in poplar. (A) Phylogenetic relationships and intron insertion; (B) Hypothetical origins of eleven poplar PC genes by retroposition and tandem duplication. The letters “R” and “T” indicate the positions where retroposition and tandem duplication have occurred, respectively. Bright green vertical line represents conserved 1 phase intron insertion position in PCLD as shown in Supplementary Figure S1.

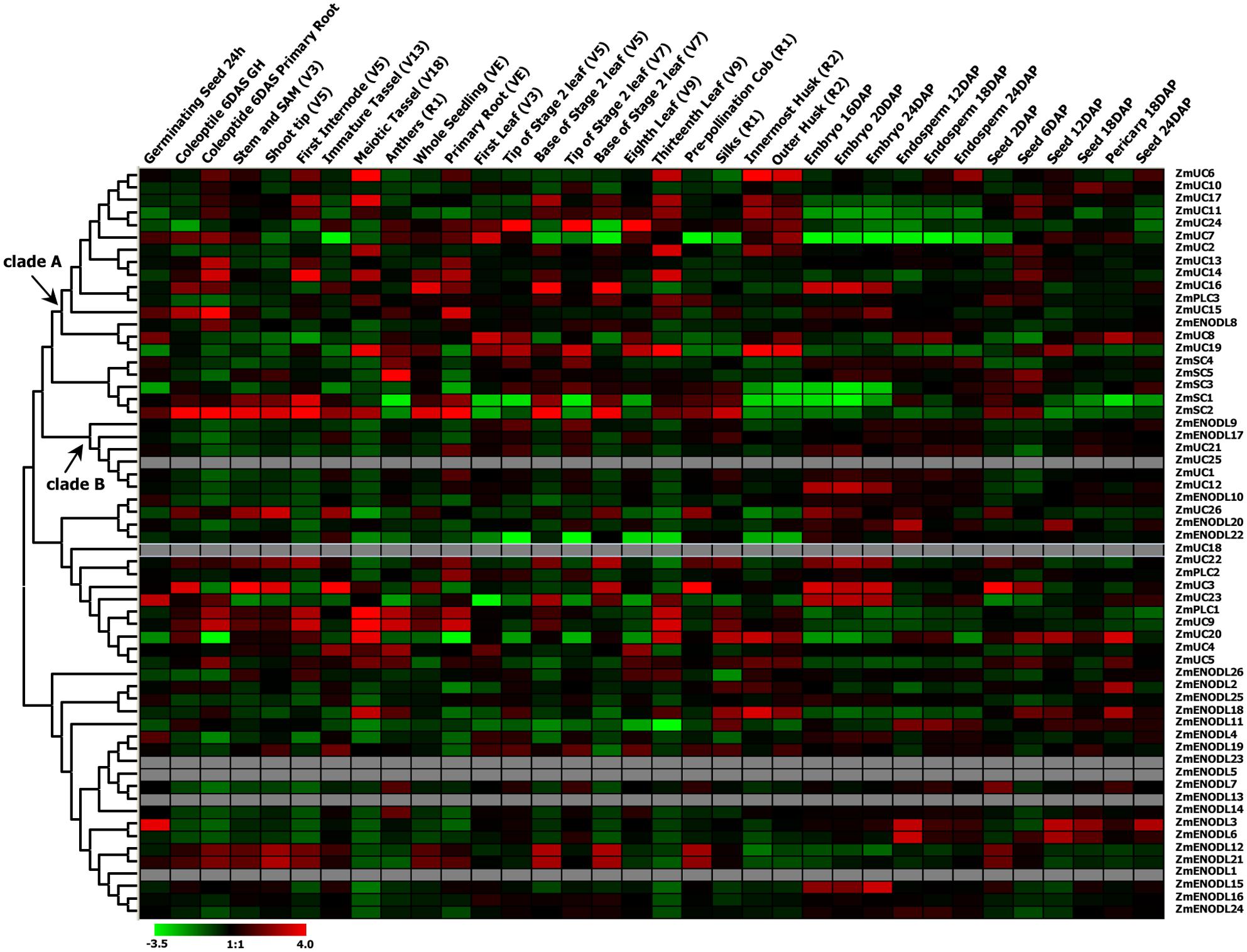

Expression Profiles of the PC Genes in Maize

We first used publicly available microarray data to detect the spatiotemporal expression patterns of the maize PC genes. Expression profiles of the PC genes were mined at 34 different tissues. Only 54 probes were detected standing for the 54 ZmPC transcripts. The remaining six transcripts with no detectable expression signal are GRMZM2G463441, GRMZM2G136879, GRMZM2G148624, GRMZM2G047208, GRMZM2G085504, and AC209987.4_FGT010. The results indicated that these genes are expressed variously in different tissues, implying that they may be involved in many growth and developmental processes (Figure 5). Such as, most ZmPC genes of clade A showed high expression levels in the root, leaf and internodes, but low expression levels in the endosperm and embryo. In contrast, ZmPC genes in clade B presented the oppositive results compared with clade A. That is, most members of clade B displayed high expression levels in the embryo and endosperm, but showed low level expression in the leaf, root and internodes. This suggested that ZmPC genes in different clades may be involved in various biological processes. Some ZmPCs were also found to be highly expressed in some specific organs, such as, ZmSC5 in anthers, ZmUC3 and ZmUC23 in embryo, suggesting that they might be involved in the growth and development of these organs in maize. Similar results have also been observed in their homologs in Arabidopsis (AtENODL1/5/6/7/11/12/16, AtAGP6/11, and FLA3; Yu et al., 2005; Levitin et al., 2008; Li et al., 2010; Ma et al., 2011), rice (OsENODL9/14/16/17; Ma et al., 2011), and B. rapa (BrENODL22/27 and BrSCL8/9; Li et al., 2013), which were highly expressed in reproductive organs. The functions of some PC genes have been investigated in several studies. For example, a sieve element-specific expressed gene (AtENODL9) may be involved in determining reproductive potential in Arabidopsis (Khan et al., 2007); AtAGP6 and AtAGP11 are involved in pollen tube growth (Levitin et al., 2008); Over expression of the FLA3 led to short siliques with low seed set due to the reduced stamen filament, suggesting that the FLA3 gene is involved in microspore development and pollen intine formation (Li et al., 2010). Next, we also investigated the expression patterns of nine ZmPCs detected in maize seedlings subjected to salt and drought treatments by qRT-PCR. The primers were listed in Table 3. The analysis revealed that these genes are differently expressed under salt and drought conditions (Figure 6). Among the nine detected ZmPC genes, all members were down-regulated under salt treatment. And five members (ZmUC19, ZmSC2, ZmENODL10, ZmUC22, and ZmENODL13) were down-regulated under drought treatment. Some rice PC genes (OsENODL19, OsENODL12, OsUCL17, OsUCL20, OsUCL7, OsUCL8, and OsUCL18) have been investigated to be down-regulated by drought and/or salt stresses (Ma et al., 2011). Interestingly, we also found that ZmUC16/21 were significantly up-regulated after drought treatment, suggesting that these ZmPCs are more likely to play key roles in maize drought response. An increasing number of evidence has suggested that PCs may also function in stress responses. Previous studies reported that some PCs, such as, OsUCL23/26/27 (Ma et al., 2011), BrUCL6/16 (Li et al., 2013), were up-regulated under drought or salt stresses. Moreover, over-expression of AtBCB/AtSC3 could confer aluminum resistance in Arabidopsis (Ezaki et al., 2001, 2005). And BcBCP1 can enhance tolerance to osmotic stress when over-expressed in tobacco (Wu et al., 2011). The differential expression profiles of different PC family genes may imply diverse roles of plant response to stress. On the other hand, PC genes which are up-regulated during several abiotic stresses are likely to be required for enhancing resistance to stress. Therefore, PCs can function in developmental processes and stress responses.

FIGURE 5. Expression profiles of the maize PC genes. Dynamic expression profiles of the maize PC genes in different development tissues.

FIGURE 6. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of nine selected ZmPC genes under the salt and drought treatments. The relative expression level of each transcript was shown here. Error bars indicate standard deviation (SD) of independent biological replicates. Asterisk indicates a significant difference from the control (∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01).

Summary

A comparative genomic analysis of the PC gene family in plants was provided in this study. This gene family had an expansion process in the course of plant evolution. A structural analysis of PCs indicated that 292 PCs contained N-terminal secretion signals and 217 PCs were expected to have GPI-anchor signals. Moreover, 281 PCs had putative arabinogalactan glycomodules and might be AGPs. The gene organization and motif composition are highly conserved in each clade, indicative of functional conservation. Most PC genes may be originated from the tandem and segmental duplications. In addition, expression profiles of the maize PC genes also provided better understanding in possible functional divergence. The results provide a base for further functional and evolutionary study of the PC gene family in plants.

Author Contributions

JC designed, supervised, and carried out parts of the experiments and wrote the manuscript. XL, YV, and LD performed the experiments. XL, YV, and LD provided material, and helped in data analysis and writing. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This project is supported by grants from the National Science Foundation of China (No. 31100923, 31200209), the National Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK2011467), the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD), and Jiangsu University “Youth Backbone Teacher Training Project” from 2012 to 2016.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2015.00515

FIGURE S1 | Motif composition of PC proteins and exon–intron organization of PCLD in plants. Conserved motif distribution of the PC proteins is displayed. Positions of the 0, 1, and 2 phase intron were shown with blue, bright green, and red vertical lines, respectively.

Footnotes

- ^ http://www.phytozome.net

- ^ http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/NetNGlyc/

- ^ http://meme.sdsc.edu

- ^ http://www.dyogen.ens.fr/genomicus/

- ^ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome

- ^ http://meme.sdsc.edu

References

Anderson, R. P., and Roth, J. R. (1977). Tandem genetic duplications in phage and bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 31, 473–505. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.31.100177.002353

Andrade, M. A., Perez-Iratxeta, C., and Ponting, C. P. (2001). Protein repeats: structures, functions, and evolution. J. Struct. Biol. 134, 117–131. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.2001.4392

Bailey, T. L., Williams, N., Misleh, C., and Li, W. W. (2006). MEME: discovering and analyzing DNA and protein sequence motifs. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, W369–W373. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl198

Björklund, A. K., Ekman, D., and Elofsson, A. (2006). Expansion of protein domain repeats. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2:e114. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020114

Björklund, A. K., Light, S., Sagit, R., and Elofsson, A. (2010). Nebulin: a study of protein repeat evolution. J. Mol. Biol. 402, 38–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.07.011

Blanc, G., and Wolfe, K. H. (2004). Functional divergence of duplicated genes formed by polyploidy during Arabidopsis evolution. Plant Cell 16, 1679–1691. doi: 10.1105/tpc.021410

Cannon, S. B., Mitra, A., Baumgarten, A., Young, N. D., and May, G. (2004). The roles of segmental and tandem gene duplication in the evolution of large gene families in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Plant Biol. 4:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-4-10

Cao, J. (2012). The pectin lyases in Arabidopsis thaliana: evolution, selection and expression profiles. PLoS ONE 7:e46944. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046944

Cao, J., Huang, J., Yang, Y., and Hu, X. (2011). Analyses of the oligopeptide transporter gene family in poplar and grape. BMC Genomics 12:465. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-465

Cao, J., and Li, X. (2015). Identification and phylogenetic analysis of late embryogenesis abundant proteins family in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum). Planta 241, 757–772. doi: 10.1007/s00425-014-2215-y

Cao, J., and Shi, F. (2012). Evolution of the RALF gene family in plants: gene duplication and selection patterns. Evol. Bioinform. Online 8, 271–292. doi: 10.4137/EBO.S9652

Cao, J., Shi, F., Liu, X., Huang, G., and Zhou, M. (2010). Phylogenetic analysis and evolution of aromatic amino acid hydroxylase. FEBS Lett. 584, 4775–4782. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.11.005

Charon, C., Bruggeman, Q., Thareau, V., and Henry, Y. (2012). Gene duplication within the Green Lineage: the case of TEL genes. J. Exp. Bot. 63, 5061–5077. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers181

Chen, K., Durand, D., and Farach-Colton, M. (2000). NOTUNG: a program for dating gene duplications and optimizing gene family trees. J. Comput. Biol. 7, 429–447. doi: 10.1089/106652700750050871

Chen, Y., and Cao, J. (2014). Comparative genomic analysis of the Sm gene family in rice and maize. Gene 539, 238–249. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2014.02.006

Chen, Y., Hao, X., and Cao, J. (2014). Small auxin upregulated RNA (SAUR) gene family in maize: Identification, evolution, and its phylogenetic comparison with Arabidopsis, rice, and sorghum. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 56, 133–150. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12127

Comeron, J. M. (1999). K-Estimator: calculation of the number of nucleotide substitutions per site and the confidence intervals. Bioinformatics 15, 763–764. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/15.9.763

D’Andrea, L. D., and Regan, L. (2003). TPR proteins: the versatile helix. Trends Biochem. Sci. 28, 655–662. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2003.10.007

Dash, S., Van Hemert, J., Hong, L., Wise, R. P., and Dickerson, J. A. (2012). PLEXdb: gene expression resources for plants and plant pathogens. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D1194–D1201. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr938

De Rienzo, F., Gabdoulline, R. R., Menziani, M. C., and Wade, R. C. (2000). Blue copper proteins: a comparative analysis of their molecular interaction properties. Protein Sci. 9, 1439–1454. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.8.1439

Dong, J., Kim, S. T., and Lord, E. M. (2005). Plantacyanin plays a role in reproduction in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 138, 778–789. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.063388

Edgar, R. C. (2004). MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 1792–1997. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340

Eisenhaber, B., Wildpaner, M., Schultz, C. J., Borner, G. H., Dupree, P., and Eisenhaber, F. (2003). Glycosylphosphatidylinositol lipid anchoring of plant proteins. Sensitive prediction from sequence- and genome-wide studies for Arabidopsis and rice. Plant Physiol. 133, 1691–701. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.023580

Ezaki, B., Katsuhara, M., Kawamura, M., and Matsumoto, H. (2001). Different mechanisms of four aluminum (Al)-resistant transgenes for Al toxicity in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 127, 918–927. doi: 10.1104/pp.010399

Ezaki, B., Sasaki, K., Matsumoto, H., and Nakashima, S. (2005). Functions of two genes in aluminium (Al) stress resistance: repression of oxidative damage by the AtBCB gene and promotion of efflux of Al ions by the NtGDI1 gene. J. Exp. Bot. 56, 2661–2671. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eri259

Fang, L., Cheng, F., Wu, J., and Wang, X. (2012). The impact of genome triplication on tandem gene evolution in Brassica rapa. Front. Plant Sci. 3:261. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2012.00261

Fedorova, M., van de Mortel, J., Matsumoto, P. A., Cho, J., Town, C. D., VandenBosch, K. A., et al. (2002). Genome-wide identification of nodule-specific transcripts in the model legume Medicago truncatula. Plant Physiol. 130, 519–537. doi: 10.1104/pp/006833

Franzke, A., Lysak, M. A., Al-Shehbaz, I. A., Koch, M. A., and Mummenhoff, K. (2010). Cabbage family affairs: the evolutionary history of Brassicaceae. Trends Plant Sci. 16, 108–116. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.11.005

Ganko, E. W., Meyers, B. C., and Vision, T. J. (2007). Divergence in expression between duplicated genes in Arabidopsis. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 2298–2309. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm158

Gaut, B. S., Morton, B. R., McCaig, B. C., and Clegg, M. T. (1996). Substitution rate comparisons between grasses and palms: synonymous rate differences at the nuclear gene Adh parallel rate differences at the plastid gene rbcL. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 10274–10279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10274

Giri, A. V., Anishetty, S., and Gautam, P. (2004). Functionally specified protein signatures distinctive for each of the different blue copper proteins. BMC Bioinformatics 5:127. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-127

Goodstein, D. M., Shu, S., Howson, R., Neupane, R., Hayes, R. D., Fazo, J., et al. (2012). Phytozome: a comparative platform for green plant genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D1178–D1186. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr944

Greene, E. A., Erard, M., Dedieu, A., and Barke, D. G. B. (1998). MtENOD16 and 20 are members of a family of phytocyanin-related early nodulins. Plant Mol. Biol. 36, 775–783. doi: 10.1023/A:1005916821224

Guss, J. M., Merritt, E. A., Phizackerley, R. P., and Freeman, H. C. (1996). The structure of a phytocyanin, the basic blue protein from cucumber, refined at 1.8 A resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 262, 686–705. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0545

Hart, P. J., Nersissian, A. M., Herrmann, R. G., Nalbandyan, R. M., Valentine, J. S., and Eisenberg, D. (1996). A missing link in cupredoxins: crystal structure of cucumber stellacyanin at 1.6 A resolution. Protein Sci. 5, 2175–2183. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560051104

Kato, T., Kawashima, K., Miwa, M., Mimura, Y., Tamaoki, M., Kouchi, H., et al. (2002). Expression of genes encoding late nodulins characterized by a putative signal peptide and conserved cysteine residues is reduced in ineffective pea nodules. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 15, 129–137. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2002.15.2.129

Kellogg, E. A. (2001). Evolutionary history of the grasses. Plant Physiol. 125, 1198–1205. doi: 10.1104/pp.125.3.1198

Khan, J. A., Wang, Q., Sjölund, R. D., Schulz, A., and Thompson, G. A. (2007). An early nodulin-like protein accumulates in the sieve element plasma membrane of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 143, 1576–1589. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.092296

Kim, S., Mollet, J. C., Dong, J., Zhang, K. L., Park, S. Y., and Lord, E. M. (2003). Chemocyanin, a small basic protein from the lily stigma, induces pollen tube chemotropism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 16125–16130. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2533800100

Koch, M. A., Haubold, B., and Mitchell-Olds, T. (2000). Comparative evolutionary analysis of chalcone synthase and alcohol dehydrogenase loci in Arabidopsis, Arabis, and related genera (Brassicaceae). Mol. Biol. Evol. 17, 1483–1498. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026248

Kong, H., Landherr, L. L., Frohlich, M. W., Leebens-Mack, J., Ma, H., and dePamphilis, C. W. (2007). Patterns of gene duplication in the plant SKP1 gene family in angiosperms: evidence for multiple mechanisms of rapid gene birth. Plant J. 50, 873–885. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03097.x

Koralewski, T. E., and Krutovsky, K. V. (2011). Evolution of exon-intron structure and alternative splicing. PLoS ONE 6:e18055. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018055

Leister, D. (2004). Tandem and segmental gene duplication and recombination in the evolution of plant disease resistance gene. Trends Genet. 20, 116–122. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2004.01.007

Levitin, B., Richter, D., Markovich, I., and Zik, M. (2008). Arabinogalactan proteins 6 and 11 are required for stamen and pollen function in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 56, 351–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03607.x

Li, J., Gao, G., Zhang, T., and Wu, X. (2013). The putative phytocyanin genes in Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa L.): genome-wide identification, classification and expression analysis. Mol. Genet. Genomics 288, 1–20. doi: 10.1007/s00438-012-0726-4

Li, J., Yu, M., Geng, L. L., and Zhao, J. (2010). The fasciclin-like arabinogalactan protein gene, FLA3, is involved in microspore development of Arabidopsis. Plant J. 64, 482–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04344.x

Li, W. H., Yang, J., and Gu, X. (2005). Expression divergence between duplicate genes. Trends Genet. 21, 602–607. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2005.08.006

Light, S., Sagit, R., Ithychanda, S. S., Qin, J., and Elofsson, A. (2012). The evolution of filamin-a protein domain repeat perspective. J. Struct. Biol. 179, 289–298. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2012.02.010

Livak, K. J., and Schmittgen, T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods 25, 402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262

Louis, A., Muffato, M., and Roest Crollius, H. (2013). Genomicus: five genome browsers for comparative genomics in eukaryota. Nucleic Acids Res. 41(Database issue), D700–D705. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1156

Ma, H., Zhao, H., Liu, Z., and Zhao, J. (2011). The phytocyanin gene family in rice (Oryza sativa L.): genome-wide identification, classification and transcriptional analysis. PLoS ONE 6:e25184. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025184

Maere, S., De Bodt, S., Raes, J., Casneuf, T., Van Montagu, M., Kuiper, M., et al. (2005). Modeling gene and genome duplications in eukaryotes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 5454–5459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501102102

Makova, K. D., and Li, W. H. (2003). Divergence in the spatial pattern of gene expression between human duplicate genes. Genome Res. 13, 1638–1645. doi: 10.1101/gr.1133803

Mashiguchi, K., Asami, T., and Suzuki, Y. (2009). Genome-wide identification, structure and expression studies, and mutant collection of 22 early nodulin-like protein genes in Arabidopsis. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 73, 2452–2459. doi: 10.1271/bbb.90407

Merchant, S. S., Prochnik, S. E., Vallon, O., Harris, E. H., Karpowicz, S. J., Witman, G. B., et al. (2007). The Chlamydomonas genome reveals the evolution of key animal and plant functions. Science 318, 245–250. doi: 10.1126/science.1143609

Misumi, O., Yoshida, Y., Nishida, K., Fujiwara, T., Sakajiri, T., Hirooka, S., et al. (2008). Genome analysis and its significance in four unicellular algae, Cyanidioschyzon merolae, Ostreococcus tauri, Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, and Thalassiosira pseudonana. J. Plant Res. 121, 3–17. doi: 10.1007/s10265-007-0133-9

Morgan, C. C., Loughran, N. B., Walsh, T. A., Harrison, A. J., and O’Connell, M. J. (2010). Positive selection neighboring functionally essential sites and disease-implicated regions of mammalian reproductive proteins. BMC Evol. Biol. 10:39. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-10-39

Nersissian, A. M., Immoos, C., Hill, M. G., Hart, P. J., Williams, G., Herrmann, R. G., et al. (1998). Uclacyanins, stellacyanins, and plantacyanins are distinct subfamilies of phytocyanins: plant-specific mononuclear blue copper proteins. Protein Sci. 7, 1915–1929. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070907

Ozturk, Z. N., Talamé, V., Deyholos, M., Michalowski, C. B., Galbraith, D. W., Gozukirmizi, N., et al. (2002). Monitoring large-scale changes in transcript abundance in drought- and saltstressed barley. Plant Mol. Biol. 48, 551–573. doi: 10.1023/A:1014875215580

Petersen, T. N., Brunak, S., von Heijne, G., and Nielsen, H. (2011). SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nat. Methods 8, 785–786. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1701

Pinyopich, A., Ditta, G. S., Savidge, B., Liljegren, S. J., Baumann, E., Wisman, E., et al. (2003). Assessing the redundancy of MADS-box genes during carpel and ovule development. Nature 424, 85–88. doi: 10.1038/nature01741

Poon, S., Heath, R. L., and Clarke, A. E. (2012). A chimeric arabinogalactanprotein promotes somatic embryogenesis in cotton cell culture. Plant Physiol. 160, 684–695. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.203075

Punta, M., Coggill, P. C., Eberhardt, R. Y., Mistry, J., Tate, J., Boursnell, C., et al. (2012). The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D290–D301. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1065

Schmutz, J., Cannon, S. B., Schlueter, J., Ma, J., Mitros, T., Nelson, W., et al. (2010). Genome sequence of the palaeopolyploid soybean. Nature 463, 178–183. doi: 10.1038/nature08670

Schultz, C. J., Rumsewicz, M. P., Johnson, K. L., Jones, B. J., Gaspar, Y. M., and Bacic, A. (2002). Using genomic resources to guide research directions. The arabinogalactan protein gene family as a test case. Plant Physiol. 129, 1448–1463. doi: 10.1104/pp.003459

Sekhon, R. S., Lin, H., Childs, K. L., Hansey, C. N., Buell, C. R., de Leon, N., et al. (2011). Genome-wide atlas of transcription during maize development. Plant J. 66, 553–563. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04527.x

Showalter, A. M., Keppler, B., Lichtenberg, J., Gu, D. Z., and Welch, L. R. (2010). A bioinformatics approach to the identification, classification, and analysis of hydroxyproline-rich glycoproteins. Plant Physiol. 153, 485–513. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.156554

Soderlund, C., Bomhoff, M., and Nelson, W. M. (2011). SyMAP v3.4: a turnkey synteny system with application to plant genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 39:e68. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr123

Sturn, A., Quackenbush, J., and Trajanoski, Z. (2002). Genesis: cluster analysis of microarray data. Bioinformatics 18, 207–208. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.1.207

Tamura, K., Peterson, D., Peterson, N., Stecher, G., Nei, M., and Kumar, S. (2011). MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121

Thomas, E. E. (2005). Short, local duplications in eukaryotic genomes. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 15, 640–644. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2005.09.008

Wang, X. Y., and Paterson, A. H. (2011). Genes conversion in angiosperm genomes with an emphasis on genes duplicated by polyploidization. Genes 2, 1–20. doi: 10.3390/genes2010001

Weiner, J. III, Beaussart, F., and Bornberg-Bauer, E. (2006). Domain deletions and substitutions in the modular protein evolution. FEBS J. 273, 2037–2047. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05220.x

Wu, H. Y., Shen, Y., Hu, Y. L., Tan, S. J., and Lin, Z. P. (2011). A phytocyaninrelated early nodulin-like gene, BcBCP1, cloned from Boea crassifolia enhances osmotic tolerance in transgenic tobacco. J. Plant Physiol. 168, 935–943. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2010.09.019

Xu, G., Ma, H., Nei, M., and Kong, H. (2009). Evolution of F-box genes in plants: different modes of sequence divergence and their relationships with functional diversification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 835–840. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812043106

Keywords: phytocyanins, expansion, evolution, expression profile, maize

Citation: Cao J, Li X, Lv Y and Ding L (2015) Comparative analysis of the phytocyanin gene family in 10 plant species: a focus on Zea mays. Front. Plant Sci. 6:515. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00515

Received: 31 March 2015; Accepted: 26 June 2015;

Published: 13 July 2015.

Edited by:

Jun Yu, Beijing Institute of Genomics, ChinaCopyright © 2015 Cao, Li, Lv and Ding. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jun Cao, Institute of Life Sciences, Jiangsu University, Xuefu Road 301, Jiangsu, Zhenjiang 212013, China, cjinfor@163.com

Jun Cao

Jun Cao Xiang Li

Xiang Li Yueqing Lv

Yueqing Lv Lina Ding

Lina Ding