- 1State Key Laboratory for Conservation and Utilization of Subtropical Agro-bioresources, College of Horticulture, South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou, China

- 2Department of Biological Sciences and Temasek Life Sciences Laboratory, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore

In angiosperms, regulation of flowering is a vital process for successful reproduction. To date, the molecular mechanism of flowering is well-studied in the model plant, Arabidopsis, in which key genes such as FLOWERING LOCUST (FT) or FD have been identified to regulate flowering. However, the flowering mechanisms are still largely unknown in fruit trees like loquat. To this end, we first cloned one FT- and two FD-like genes from the loquat (Eriobotrya deflexa Nakai f. koshunensis) and referred to as EdFT, EdFD1, and EdFD2, respectively. Phylogenetic analysis has shown that EdFT, EdFD1, and EdFD2 are conserved during the evolution process. EdFT is mainly expressed in reproductive tissues (e.g., flower buds, flowers, and fruits), while EdFD1 and EdFD2 are mainly expressed in apical buds including leaf buds and flower buds. EdFT is localized in the whole cell, while EdFD1 or EdFD2 is localized in the nucleus. Ectopic expression of EdFT, EdFD1, and EdFD2 in Arabidopsis results in early flowering. In addition, we have also revealed that the EdFT interacts with both EdFD1 and EdFD2. Overall, these data suggest that the EdFT, EdFD1, and EdFD2 are the functional homologs of FT and FD, respectively, which might act together to regulate loquat flowering through a similar mechanism found in Arabidopsis.

Introduction

In angiosperms, flowering, known as a key process of the transition from vegetative to reproductive growth, is crucial for plant reproductive success. The initiation of flowering is coordinately regulated via the integration of external and internal signals, including photoperiod, temperature, plant age, and gibberellic acid (Wellmer and Riechmann, 2010; Song et al., 2013). During the past few decades, extensive studies in the model plant Arabidopsis have identified different floral signaling pathways, where different types of flowering time genes act in response to various factors (Amasino, 2010; Wellmer and Riechmann, 2010; Andres and Coupland, 2012). Notably, these signaling pathways finally converged on a floral pathway integrator, FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT), which serves as the component of the long-sought florigen (Pennisi, 2007; Turck et al., 2008; Song et al., 2013; Blumel et al., 2015).

FT mRNA is expressed in leaves and its protein moves to the shoot apex through the phloem to promote flowering (Corbesier et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2013a). FT encodes a phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein (PEBP), whose family consists of three phylogenetically distinct groups: FT-like proteins, TERMINAL FLOWER1-like (TFL1) proteins and MOTHER OF FT AND TFL1-like (MFT) proteins (Pin and Nilsson, 2012; Wickland and Hanzawa, 2015). MFT-like genes are in the basal clade and are considered as the ancestors of FT and TFL1-like genes. In Arabidopsis, the PEPB family comprises six genes including FT, TFL1, MFT, TWIN SISTER OF FT (TSF), BROTHER OF FT (BFT), and ARABIDOPSIS THALIANA RELATIVE OF CENTRORADIALIS (ATC; Matsoukas et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2013). TSF, a member of the FT-like clade, is also produced in the phloem companion cells, and then transported to the apex to trigger flowering (Jang et al., 2009). In contrast to FT-like genes, TFL1, BFT, and ATC have antagonistic function in flowering and are classified into the TFL1-like clade (Yoo et al., 2010; Huang et al., 2012).

FT is transported to the shoot apex, where it interacts with FD to induce flowering in Arabidopsis and Oryza sativa (Hayama et al., 2003; Tsuji et al., 2013). FD, encoding a bZIP transcription factor, is mainly expressed in the shoot apex during floral induction (Wigge et al., 2005). In Arabidopsis, FT and FD are found to interact with each other both in vivo and in vitro, and the FT–FD complex directly activates the floral meristem identity genes like APETALA1 (AP1) through binding to its promoter (Abe et al., 2005; Wigge et al., 2005). The mutation in FD results in late flowering and suppresses the early flowering phenotype of FT overexpression lines, suggesting that FD mediates the function of FT in regulating flowering (Wigge et al., 2005). In addition to the extensive studies in Arabidopsis, FT and FD have also been identified in other plants such as tomato (Pnueli et al., 2001; Lifschitz and Eshed, 2006), pea (Sussmilch et al., 2015), kiwifruit (Varkonyi-Gasic et al., 2013), rose (Randoux et al., 2014), strawberry (Mouhu et al., 2009), poplar (Bohlenius et al., 2006; Hsu et al., 2006; Tylewicz et al., 2015), Satsuma mandarin (Endo et al., 2005; Nishikawa et al., 2007), and apple (Kotoda et al., 2010; Guitton et al., 2012). Functional characterization of these genes has revealed that they have a conserved role in regulating flowering.

Loquat (Eriobotrya Lindl.) is a subtropical evergreen fruit tree in the apple subfamily (maloideae; rosaceae). Unlike other rosaceous fruits, such as apple, strawberry and peach, that are widely cultivated in the world, loquat is mainly distributed throughout Southeast Asia and Mediterranean countries and regions. It is famous as a tasty fruit that has rich nutrition and ripens at off seasons, and also as a medicinal plant that contains many pharmaceutical compounds (Hong et al., 2008). The cultivated loquat (Eriobotrya japonica Lindl.), which is the only edible specie of genus Eriobotrya, blooms in fall or early winter (Lin et al., 1999). Besides the cultivated loquat, there are a lot of wild species in Eriobotrya (Lin, 2007) that demonstrate different flowering time. For example, E. deflexa Nakai flowers in spring (Wu and Peter, 2003), which is similar to the other Rosaceae plants. In China, we have observed that the same loquat variety grown in different places may blossom and yield fruits in different seasons. The similar phenomenon is also observable in other fruit trees. Thus, we aim to study the flowering mechanisms of loquat to understand the molecular basis of various flowering patterns. This will help us to determine how to optimize loquat yield in different climatic areas. So far molecular studies on loquat flowering are still limited, and have mostly focused on the cultivated loquat. Two LEAFY (LFY) and two TFL1 orthologous genes have been cloned from the cultivated loquat (Esumi et al., 2005). In addition, one EjAP1 has been isolated from ‘Zaozhong No. 6.’ Ectopic expression of this gene in the Arabidopsis ap1-1 mutant rescues sepal and petal development (Liu et al., 2013b), indicating the functional convervation of floral meristem identity genes between loquat and Arabidopsis.

In this study, we cloned one FT- and two FD-like genes from E. deflexa Nakai f. koshunensis, and named them EdFT, EdFD1, and EdFD2, respectively. Sequence analyses, expression studies, and functional characterization of these loquat genes in Arabidopsis suggest that these three genes may evolve to have some unique functions in loquat development in addition to similar roles in regulating flowering time to their Arabidopsis orthologs.

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

Wild loquat (E. deflexa Nakai f. koshunensis) was selected for this research. Loquat trees were grown under natural conditions in the loquat germplasm resource preservation garden, South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou, China. The wild type Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype Col was used for gene transformation. Nicotiana benthamiana was grown for transient expression. Arabidopsis and tabacco were grown under long-day conditions (16 h light/8 h dark) at 22°C.

Gene Isolation and Sequence Analysis

The full-length coding sequences of EdFT, EdFD1, and EdFD2 were amplified from the cDNA prepared from loquat leaves using Phusion DNA Polymerase (Thermo, USA). Subsequently, the PCR products were cloned into pGEM-T easy vector (Promega, USA). The primers used for gene cloning were listed in Supplementary Table S1. Amino acid sequences were aligned using ClustalX and BioEdit. Phylogenetic analyses were performed using MEGA by the Neighbor-Joining (N-J) method with 1000 bootstrap replications. The identity of the nucleotide and amino acid between EdFD1 and EdFD2 was analyzed using DNAMAN V6.0. The sequences of the EdFT and two EdFD genes was deposited in GenBank, the accession numbers are KU319433 (EdFT), KU319434 (EdFD1), and KU319435 (EdFD2).

Vector Construction

To construct 35S:EdFD1/2-6HA, the EdFD1/2 coding sequences were amplified and introduced into pGreen-35S-6HA vector (Hou et al., 2014). To produce 35S:EdFT/EdFD1/EdFD2-GFP, EdFT/EdFD1/EdFD2 coding sequences were cloned into pGreen-35S-GFP (Lee et al., 2012). For the bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assay, 35S:EdFT-cYFP and 35S:nYFP-EdFD1/2 were constructed by cloning EdFT and EdFD1/2 into pGreen-35S-cYFP/nYFP (Hou et al., 2014). All constructed vectors were confirmed by sequencing. All of the primers used for vector construction were listed in Supplementary Table S2.

Arabidopsis Transformation

The constructed vectors were introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101::psoup and then transformed into Arabidopsis Col using the floral dip method (Zhang et al., 2006). Transgenic lines were screened on soil by Basta.

Transient Expression in Nicotiana benthamiana

For observing the subcellular localization of EdFT, EdFD1 and EdFD2, and the BiFC analysis, Agrobacterium-mediated transient transformation in N. benthamiana leaves was performed as previously described (Sparkes et al., 2006). After transformation, fluorescent signals were observed under the fluorescence microscope (Observer.D1, Zeiss, Germany) or the confocal microscope (510 Meta, Zeiss, Germany).

Gene Expression Analysis

The total RNA was isolated by EASYspin Plus plant RNA extraction kit (aidlab, China), and the cDNAs were synthesized using PrimeScriptTM RT reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (TaKaRa, Japan). Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was performed using iTaqTM universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, USA) in the LightCycler 480 (Roche). The specificity of primers was confirmed by melting curve analysis and sequencing. The PCR efficiency was measured by standard curve in the LightCycler® 480 SW 1.5 software. And primers with specific amplification and efficiency about 2.0 were applied to test primer efficiency. Gene expression levels were normalized against loquat ACT4 (JX089589). Semi-quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) was used for detecting exogenous gene expression in Arabidopsis overexpression lines. TUB2 (AT5G62690) was amplified as an internal control. The primers used were shown in Supplementary Table S3. All the expression analysis were applied with three technical replicates and two biological replicates.

Data Analysis

The significance of the differences between data was evaluated with the Student t-test. Calculations were carried out using Microsoft Excel software.

Results

Identification of FT and FD Orthologs from E. deflexa Nakai f. koshunensis

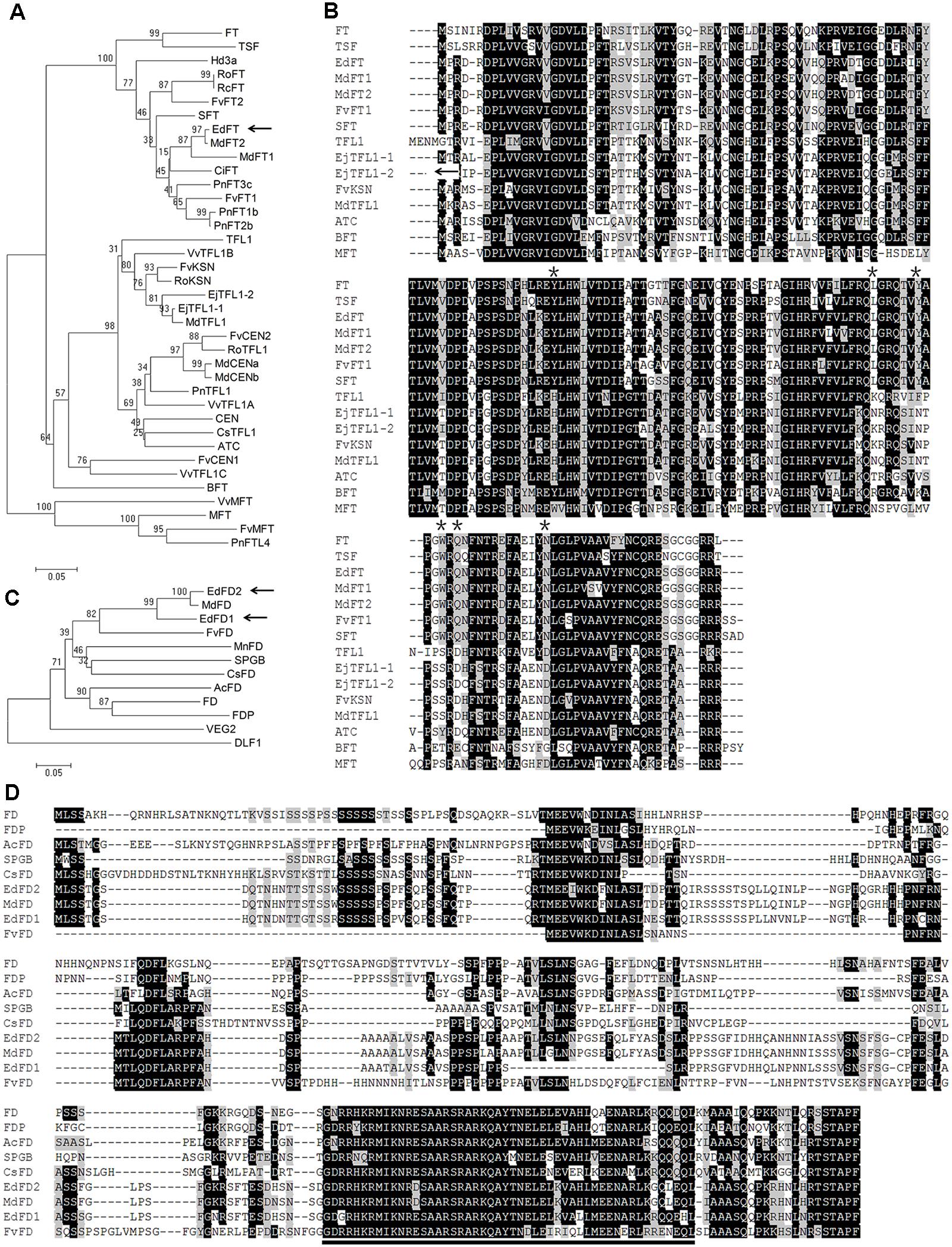

Since FT and FD in Arabidopsis and their orthologs in other plant species have shown important roles in regulating flowering time, we first isolated one FT- and two FD-like genes from E. deflexa Nakai f. koshunensis, and named them EdFT, EdFD1, and EdFD2, respectively (Supplementary Figure S1). FT encodes a protein of PEBP family. Phylogenetic analysis of EdFT and six Arabidopsis PEBP family proteins showed that EdFT was classified into the FT clade (Figure 1A). Although the amino acid sequence of FT shares high similarity to that of TFL1, they play antagonistic roles in regulating flowering time in Arabidopsis. Substitution of single critical amino acid residue leads to the function conversion between FT and TFL1, and vice versa (Hanzawa et al., 2005; Ho and Weigel, 2014). Sequence alignment revealed that the critical amino acid residues in EdFT were identical to those in FT rather than those in TFL1 (Figure 1B; asterisks indicate the critical sites). In addition, EdFT showed the highest sequence similarity to MdFT homologs (99% identity to MdFT2, and 94% to MdFT1), which were isolated from Malus × domestica in the same subfamily of Maloideae as loquat.

FIGURE 1. Sequence analysis of EdFT and EdFDs. (A) Phylogenetic analysis of plant PEBP family proteins. The accession number of each gene is as follows: FT (Arabidopsis thaliana, AT1G65480), TFL1 (AT5G03840), TSF (AT4G20370), MFT (AT1G18100), BFT (AT5G62040), ATC (AT2G27550), SFT (Solanum lycopersicum, AY186735), EjTFL1-1 (Eriobotrya japonica, AB162045), EjTFL1-2 (AB162051), MdFT1 (Malus× domestica, AB161112), MdFT2 (AB458504), MdTFL1 (AB052994), MdCENa (AB366641), MdCENb (AB366642), FvFT1 (Fragariavesca, JN172098), FvFT2 (XM_004297225), FvCEN1 (XM_004308059), FvCEN2 (XM_004291562), FvKSN (HQ378595), FvMFT (XM_004299493), RoFT (Rosa luciae, FM999826), RoTFL1 (FM999796), RoKSN (HQ174211), RcFT (Rosa chinensis, FR729041), CiFT (Citrus unshiu, AB027456), PnFT1b (Populus nigra, AB161109), PnFT2b (AB161108), PnFT3c (AB161107), PnTFL1 (AB369067), PnFTL4 (AB181241), Hd3a (Oryza sativa, AB052941), CEN (Antirrhinum, S81193), CsTFL1 (Chrysanthemum seticuspe, AB839767), VvTFL1A (Vitis vinifera, DQ871591), VvTFL1B (DQ871592), VvTFL1C (DQ871593), VvMFT (DQ871594). Arrows indicate the EdFT gene. (B) Amino acid sequence alignment of several plant PEBP family proteins showed in (A). Amino acid residues in black and gray represent 100 and 50% similarity respectively. The asterisks indicate the critical amino acid positions. (C) Phylogenetic analysis of plant FD proteins. The accession number of each gene is as follows: FD (AT4G35900), FDP (AT2G17770), AcFD (Actinidia chinensis, JX417425), SPGB (Solanum lycopersicum, EF136919), MnFD (Morus notabilis, XM_010115002), VEG2 (Pisum sativum, KP739949), CsFD (Chrysanthemum seticuspe, AB839769), DLF1 (Zea mays, NM_001112492), MdFD (Malus × domestica, XM_008339760), FvFD (Fragaria vesca, XM_004289026). Arrows indicate the EdFD1/2 genes. (D) Amino acid sequence alignment of several plant FD proteins showed in (C). Amino acid residues in black and gray represent 100 and 50% similarity, respectively. The bZIP domain is underlined.

FD is a bZIP protein and interacts with FT to activate the floral meristem identity genes in Arabidopsis (Abe et al., 2005; Wigge et al., 2005). In loquat, we also isolated two FD-like genes, EdFD1 and EdFD2. They shared high sequence similarity to each other, with 83.93% identity at the nucleotide level and 84.31% identity at the amino acid level. Phylogenetic analysis showed that EdFD1 and EdFD2 were similar to the reported FD proteins, especially those from Rosaceae (Figure 1C). The amino acid sequence alignment also showed that EdFD1 and EdFD2 contained a bZIP domain, which is conserved in other FD proteins (Figure 1D).

Tissue-Specific Expression Patterns of EdFT and EdFDs in Loquat

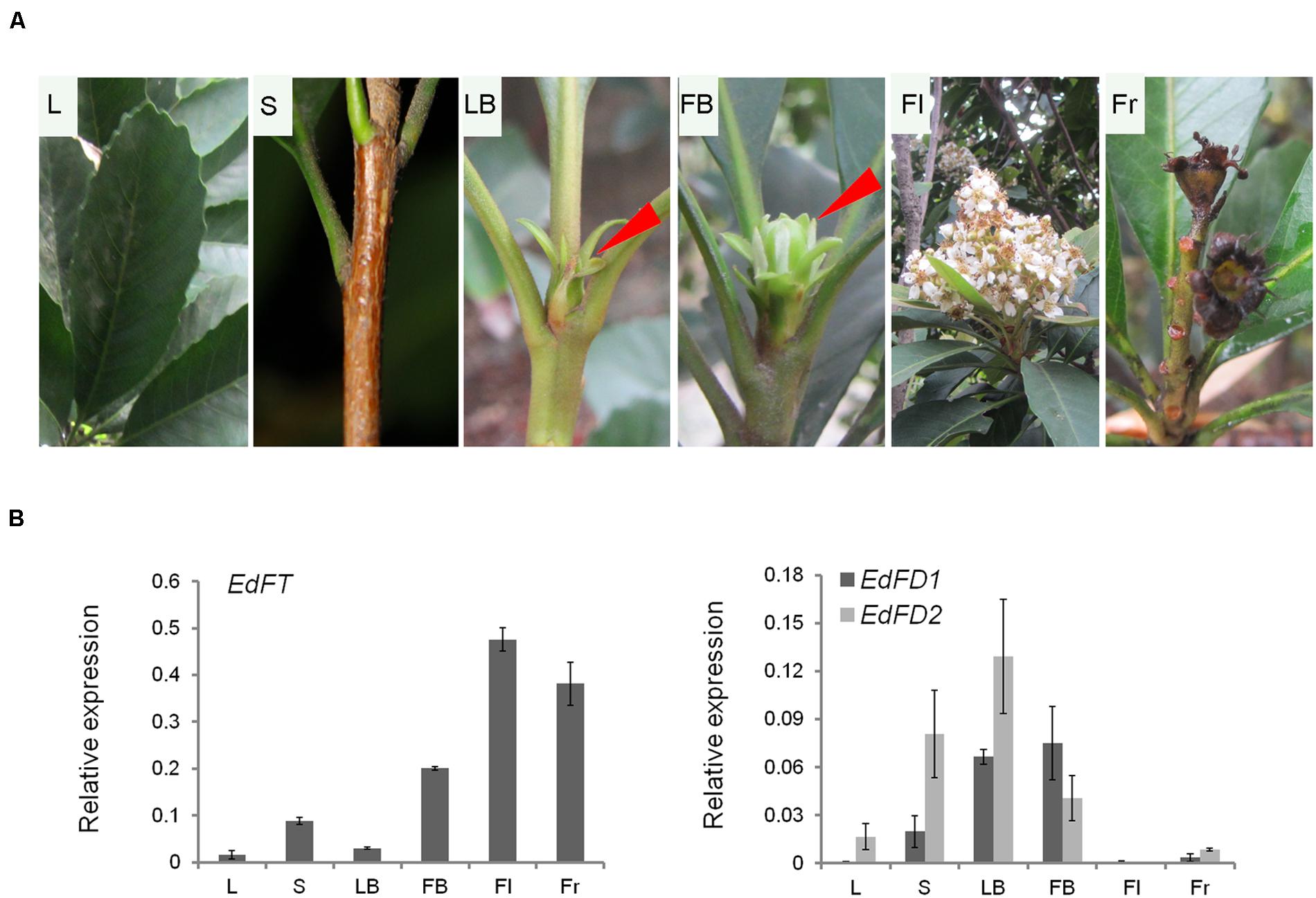

To understand the potential function of EdFT and EdFDs in loquat, we examined the expression pattern of EdFT and EdFDs using qPCR in various tissues of E. deflexa Nakai f. koshunensis, including leaves, shoots, leaf buds, flower buds, flowers, and fruits (Figure 2A).

FIGURE 2. Tissue-specific expression of EdFT, EdFD1, and EdFD2 in loquat. (A) Different tissue phenotype from the loquat Eriobotrya deflexa Nakai f. koshunensis. (B) Relative expression of EdFT, EdFD1, and EdFD2 in different tissue showed in (A). Loquat ACT4 gene serves as an internal control. L, leaf; S, shoot; LB, leaf buds; FB, flower buds; Fl, flower; Fr, fruit.

EdFT was highly expressed in flower buds, flowers and fruits, which was similar to the expression patterns of its orthologs in apple and kiwifruit (Kotoda et al., 2010; Varkonyi-Gasic et al., 2013). Unlike FT in Arabidopsis, which is highly expressed in leaves (Corbesier et al., 2007), EdFT expression levels were low in leaves (Figure 2B). This suggests that EdFT might also participate in the development of flowers and fruits in addition to its expected function in regulate flowering.

EdFD1 and EdFD2 were expressed with a comparable pattern. Their expression levels were high in leaf buds and flower buds, but low in leaves, flowers, and fruits (Figure 2B). In Arabidopsis, FD is mainly expressed in the shoot apex before the floral transition, while during the floral transition, FD interacts with the uploaded FT protein in the shoot apex to co-regulate the subsequent floral meristem development (Wigge et al., 2005). Interestingly, we found that EdFT, EdFD1, and EdFD2 were all expressed at relatively high levels in flower buds (Figure 2B), implying that EdFD1/EdFD2 might interact with EdFT in flower buds to co-regulate flower development in loquat.

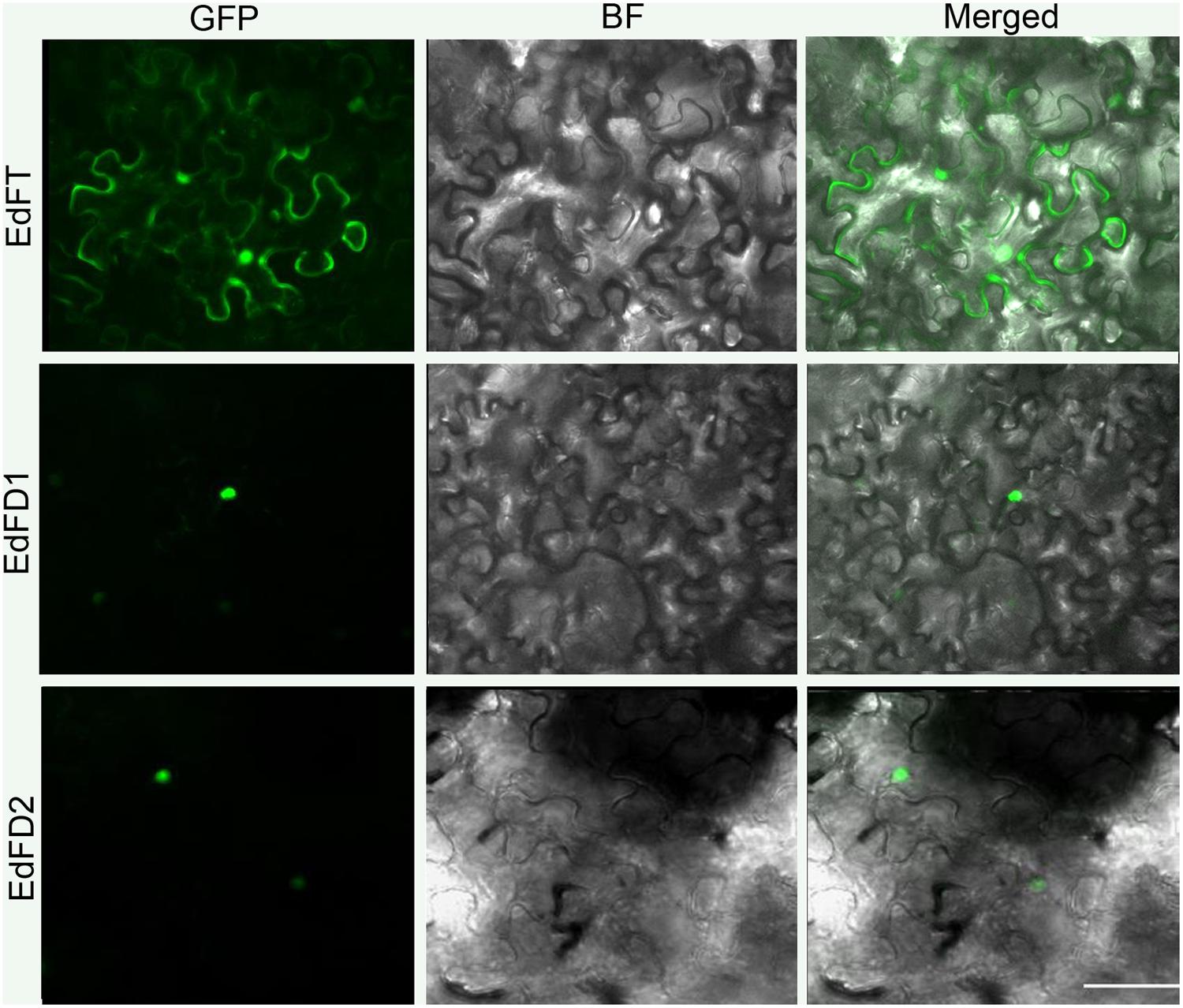

Subcellular Localization of EdFT and EdFDs

We further examined the subcellular localization of EdFT and EdFDs by fusing the green fluorescent protein (GFP) at their C-terminal regions. The resulting constructs driven by the 35S promoter were then transiently expressed in leaf epidermal cells of N. benthamiana. EdFT-GFP was localized in both the cytoplasm and nucleus, while EdFD1-GFP and EdFD2-GFP were only detected in the nucleus (Figure 3). These subcellular localization patterns are similar to those of FT and FD in Arabidopsis (Abe et al., 2005).

FIGURE 3. Subcellular localization of EdFT and EdFDs. GFP, GFP fluorescence; BF, bright-field; Merged, merged image of GFP and BF. Bar represents 50 μm.

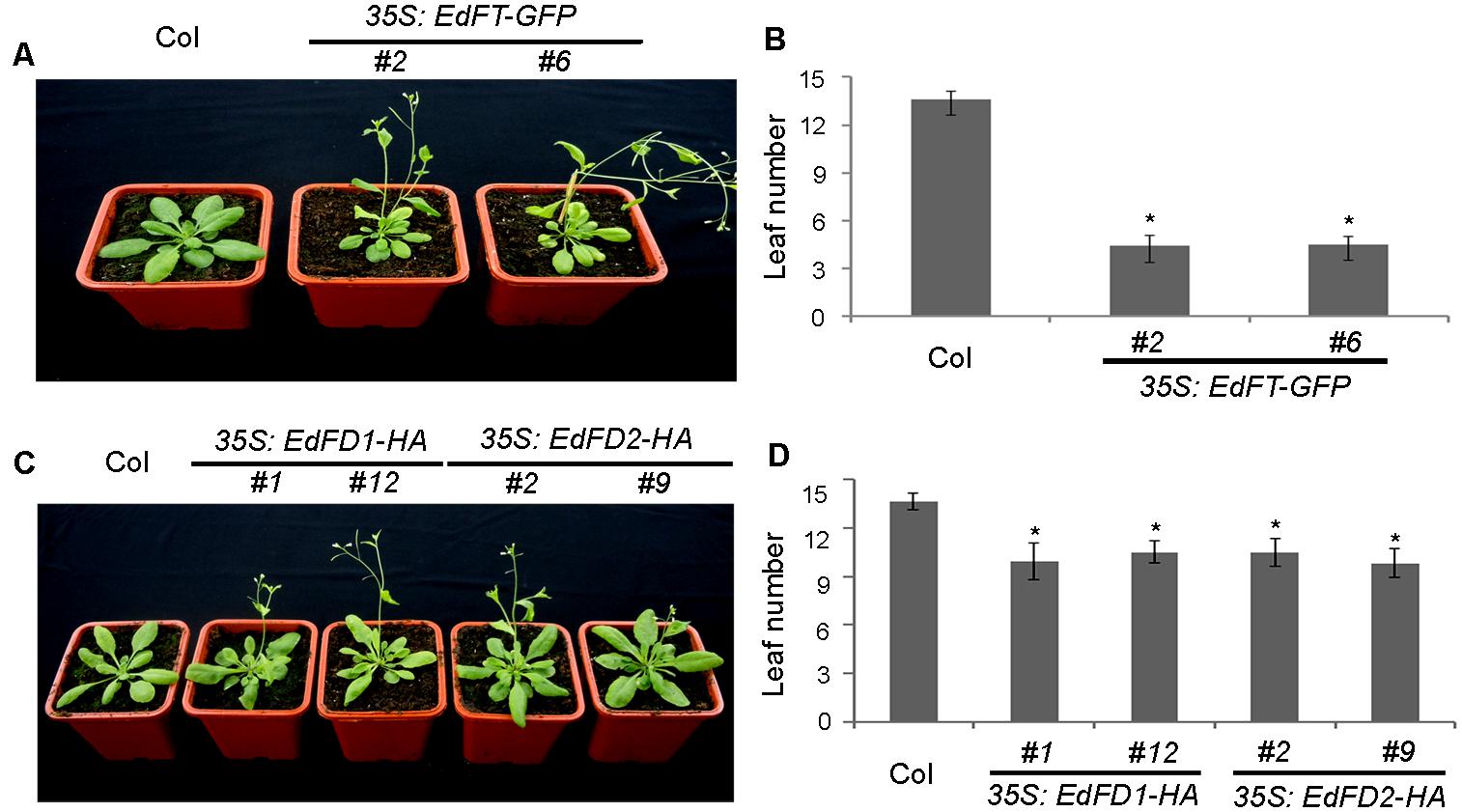

EdFT and EdFDs Accelerate Flowering in Arabidopsis

To further determine whether EdFT and EdFDs play a role in regulating flowering time, we generated 35S:EdFT-GFP, 35S:EdFD1-HA, and 35S:EdFD2-HA transgenic Arabidopsis plants. We obtained more than 10 independent transgenic lines for each construct, and two lines of each genotype at the homozygous T3 generation with ectopic gene expression (Supplementary Figure S2) were selected for further investigation. 35S:EdFT-GFP, 35S:EdFD1-HA, and 35S:EdFD2-HA transgenic lines displayed earlier flowering than Col wide-type plants under long-day conditions (Figures 4A–D). Wild-type plants flowered with 13–14 rosette leaves. In contrast, 35S:EdFT-GFP transgenic lines flowered with only 3–5 rosette leaves, while 35S:EdFD1-HA and 35S:EdFD2-HA transgenic lines produced about 10 rosette leaves (Figures 4B,D). These results suggest that EdFT, EdFD1, and EdFD2 play a conserved role in accelerating flowering in Arabidopsis.

FIGURE 4. Overexpression of EdFT and EdFDs in Arabidopsis accelerates flowering. (A) 35S:EdFT-GFP exhibits earlier flowering than wild type Col plants. (B) Rosette leaf number of Col and 35S:EdFT-GFP transgenic lines. (C) 35S:EdFD1-HA and 35S:EdFD2-HA exhibit earlier flowering than wild type Col plants. (D) Rosette leaf number of Col and 35S:EdFD1/2-HA transgenic lines. Asterisks indicate significant differences between Col and transgenic lines (n ≥ 10, p < 0.05, by Student’s t-test).

EdFT Interacts with EdFDs In vivo

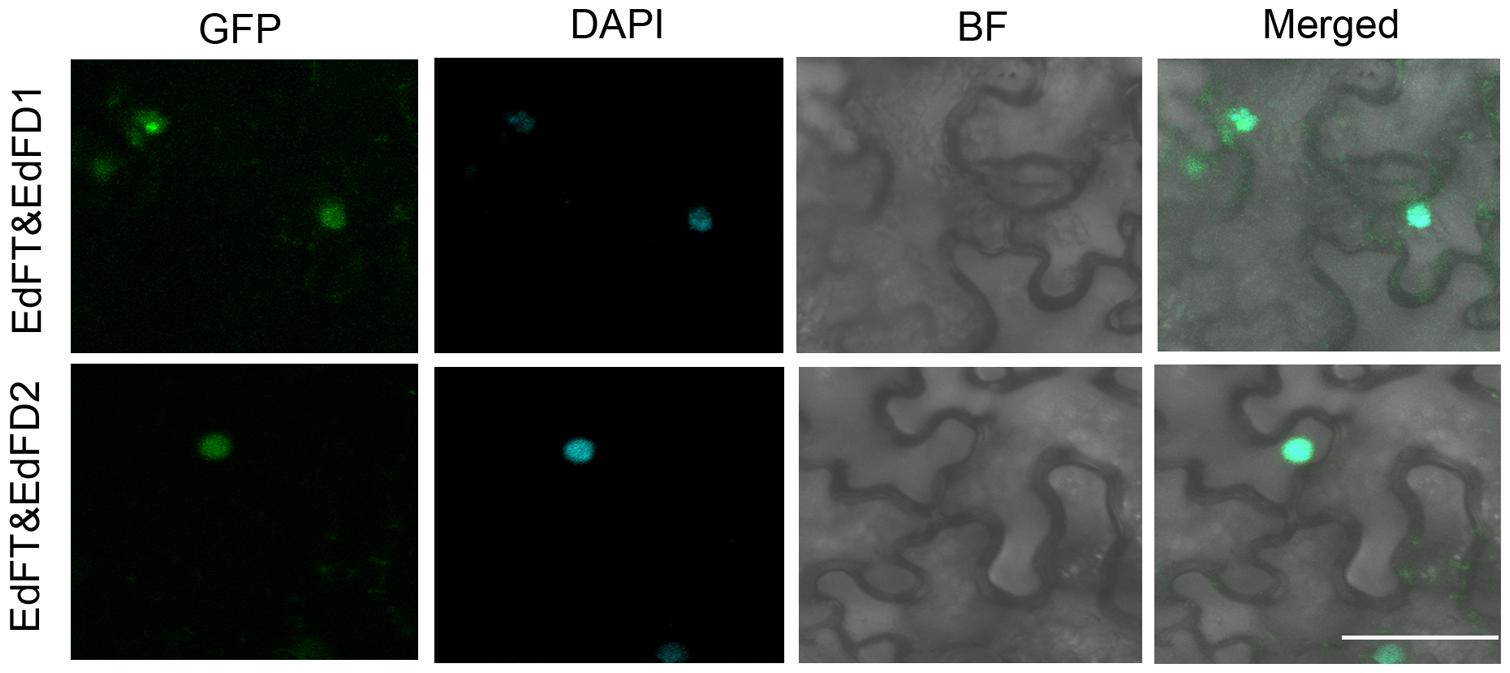

We further tested whether EdFT is able to interact with EdFD1 and EdFD2 as their counterparts in Arabidopsis using BiFC analysis. We constructed 35S:EdFT-cYFP and 35S:nYFP-EdFD1 and 35S:nYFP-EdFD2 vectors. BiFC analysis clearly showed that the fluorescent signal could be detected in nuclei when EdFT-cYFP and nYFP-EdFD1 or nYFP-EdFD2 were co-expressed in N. benthamiana leaves (Figure 5), while the interaction was not observed in both EdFT-cYFP&nYFP and cYFP&nYFP-EdFD1/2 controls (Supplementary Figure S3). These results demonstrate the direct interaction of EdFT and EdFD1/2 in the nuclei of living plant cells.

FIGURE 5. Bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) analysis shows the protein interaction between EdFT and EdFDs. EdFT&EdFD1, coexpression of 35S:EdFT-cYFP and 35S:nYFP-EdFD1; EdFT&EdFD2, coexpression of 35S:EdFT-cYFP and 35S:nYFP-EdFD2. GFP, GFP fluorescence; DAPI, fluorescence of 4, 6-diamino-2-phenylindol; BF, bright-field; Merged, merged image of GFP, DAPI, and BF. Bar represents 50 μm.

Discussion

In this study, we have isolated loquat genes, EdFT, EdFD1 and EdFD2, from E. deflexa Nakai f. koshunensis. Sequence analysis of the deduced amino acids indicates their potential functional conservation with other reported orthologs in different flowering plants (Figure 1 and Supplementary Figure S1). EdFT is expressed in flower buds, flowers and fruits, while EdFD1 and EdFD2 are expressed highly in leaf buds and flower buds (Figure 2). EdFT interacts with two EdFDs in the nucleus (Figure 5) in N. benthamiana. Furthermore, ectopic expression of these genes promotes Arabidopsis flowering (Figure 4). Taken together, these data suggest that EdFT and EdFDs are the loquat orthologs of Arabidopsis FT and FD proteins, respectively, and imply that there is a possibly conserved flowering regulatory mechanism involving these regulators in loquat.

In angiosperms, flowering is a vital transition from vegetative to reproductive growth. Proper timing of this process is a crucial factor that determines plant reproductive success. FT, as a component of long-sought florigen (Pennisi, 2007; Turck et al., 2008), has attracted a wide attention for investigating the floral transition. A large number of FT-like genes have been identified in various annual and perennial plants. Although most of the identified FT homologs have been shown to promote flowering, several FT-like genes have also been reported to likely evolve with new functions. In biennial cultivated sugar beet, flowering time is controlled by two FT genes (BvFT1 and BvFT2) that exhibit antagonistic functions. BvFT2 is required for flowering, whereas BvFT1 represses flowering (Pin et al., 2010). In perennial poplar, expression of FT1 and FT2 is temporally and spatially separated. FT1 initiates the transition from vegetative to reproductive growth, whereas FT2 promotes the vegetative growth (Bohlenius et al., 2006; Hsu et al., 2011). Furthermore, FT-like genes have evolved to regulate stomata in Arabidopsis (Kinoshita et al., 2011), control tuberization in potato (Navarro et al., 2011), drive heterosis for yield in tomato (Krieger et al., 2010), mediate seasonal growth cessation and bud set in poplar (Bohlenius et al., 2006), and affect leaf and fruit development in apple (Mimida et al., 2011). In loquat, based on the transcriptome analysis of E. deflexa Nakai f. koshunensis leaves (unpublished data), only one FT homolog has so far been identified. In this study, ectopic expression of this FT ortholog implies a similar function in regulating flowering in loquat. In addition, high expression of EdFT in fruits implies that EdFT might also be engaged in regulating fruit development in loquat, which might be investigated in future studies. In the work, we cloned and characterized two orthologous EdFDs. These two EdFDs both could interact with EdFT in the nucleus, and promote flowering when they were ectopically expressed in Arabidopsis. However, whether these two EdFDs accelerate flowering through distinct modes, or have distinct roles in the interaction with EdFT, is needed to be elucidated in further study.

Flowering is influenced by multiple environmental cues, such as day length (photoperiod) and temperature (Andres and Coupland, 2012; Song et al., 2013), which mostly regulate flowering through FT. In Arabidopsis, long-day conditions induce B-box transcriptional factor CONSTANS (CO) to directly bind to the FT promoter to initiate flowering (Wenkel et al., 2006; Tiwari et al., 2010). The CO/FT regulatory model is probably conserved in most flowering plants (e.g., rice and poplar; Hayama et al., 2003; Bohlenius et al., 2006). Temperature, including the winter temperature and ambient temperature (Andres and Coupland, 2012; Song et al., 2013), is another key environmental signal that affects flowering time via other transcription factors in either the vernalization or the thermosensory pathway. In the vernalization pathway, FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC), a MADS-box transcription factor that directly suppresses FT expression (Helliwell et al., 2006), is epigenetically silenced after a prolonged period of cold in winter, thus derepressing FT to initiate flowering (Swiezewski et al., 2009; Heo and Sung, 2011; Song et al., 2012). In the thermosensory flowering pathway, recent studies have shown a bHLH transcription factor PHYTOCHROME-INTERACTING FACTOR 4 (PIF4), a MYB transcription factor EARLY FLOWERING MYB PROTEIN (EFM), and two MADS-box transcription factors FLOWERING LOCUS M (FLM) and SHORT VEGETATIVE PHASE (SVP) play important roles in regulating flowering time through regulating FT expression in response to ambient temperature (Kumar et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2013; Pose et al., 2013; Yan et al., 2014). Based on observation of loquat growth in our germplasm resource preservation garden and some other provinces (e.g., Yunnan) in China, we have found that loquat can adjust appropriate flowering time after being transplanted. For example, E. deflexa Nakai f. koshunensis used in this study flowers in autumn–winter (October–January) in our garden, where as it flowers in spring (March) in the original place (Taiwan). The plasticity of various flowering patterns exhibited by loquat implies their ability of adjusting their responses to new environment signals to acclimatize themselves for the successful reproduction in new cultivation plots. In agreement with extensive studies in various flowering plants showing that flowering signal pathways mostly converge on the floral integrators FT and its orthologs, our study suggests that the FT ortholog in loquat could similarly play a critical role in mediating loquat response to various environmental signals. Further investigation of loquat orthologs of FT upstream regulators, such as CO, FLC, PIF4, EFM, FLM, or SVP transcription factors, could shed new light on flowering mechanisms in loquat.

Conclusion

We characterized one FT- and two FD-like genes in loquat (E. deflexa Nakai f. koshunensis). And this study showed they were the functional homologs of Arabidopsis FT and FD, respectively. The EdFT and EdFDs promoted flowering in the ectopically expressed Arabidopsis. However, whether other FT orthologs exist in loquat? Do the two EdFDs accelerate flowering through distinct modes, or have distinct roles in the interaction with EdFT? And how do the environmental factors influence loquat flowering through EdFT? The further investigation will help unravel more details underlying these issues, and will facilitate in understanding the unique mechanism of loquat flowering time regulation.

Author Contributions

LZ, SL, and YG designed and performed research. LZ, HY, SL, and YG wrote the paper.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Xingliang Hou for providing pGreen-35S-6HA, pGreen-35S-GFP, and pGreen-35S-cYFP/nYFP plasmids and Arabidopsis seeds. This study was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation (No. 31200216), State Key Laboratory for Conservation and Utilization of Subtropical Agro-bioresources (No. 201504010028, from Guangzhou municipal government), Innovation and Utilization for Germplasm Resources of Guangdong (No. 2014A030304057, 2015A030303015).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2016.00008

References

Abe, M., Kobayashi, Y., Yamamoto, S., Daimon, Y., Yamaguchi, A., Ikeda, Y., et al. (2005). FD, a bZIP protein mediating signals from the floral pathway integrator FT at the shoot apex. Science 309, 1052–1056. doi: 10.1126/science.1115983

Amasino, R. (2010). Seasonal and developmental timing of flowering. Plant J. 61, 1001–1013. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04148.x

Andres, F., and Coupland, G. (2012). The genetic basis of flowering responses to seasonal cues. Nat. Rev. Genet. 13, 627–639. doi: 10.1038/Nrg3291

Blumel, M., Dally, N., and Jung, C. (2015). Flowering time regulation in crops - what did we learn from Arabidopsis? Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 32, 121–129. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2014.11.023

Bohlenius, H., Huang, T., Charbonnel-Campaa, L., Brunner, A. M., Jansson, S., Strauss, S. H., et al. (2006). CO/FT regulatory module controls timing of flowering and seasonal growth cessation in trees. Science 312, 1040–1043. doi: 10.1126/science.1126038

Corbesier, L., Vincent, C., Jang, S. H., Fornara, F., Fan, Q. Z., Searle, I., et al. (2007). FT protein movement contributes to long-distance signaling in floral induction of Arabidopsis. Science 316, 1030–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.1141752

Endo, T., Shimada, T., Fujii, H., Kobayashi, Y., Araki, T., and Omura, M. (2005). Ectopic expression of an FT homolog from Citrus confers an early flowering phenotype on trifoliate orange (Poncirus trifoliata L. Raf.). Transgenic. Res. 14, 703–712. doi: 10.1007/s11248-005-6632-3

Esumi, T., Tao, R., and Yonemori, K. (2005). Isolation of LEAFY and TERMINAL FLOWER 1 homologues from six fruit tree species in the subfamily Maloideae of the Rosaceae. Sex. Plant Reprod. 17, 277–287. doi: 10.1007/s00497-004-0239-3

Guitton, B., Kelner, J. J., Velasco, R., Gardiner, S. E., Chagne, D., and Costes, E. (2012). Genetic control of biennial bearing in apple. J. Exp. Bot. 63, 131–149. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err261

Hanzawa, Y., Money, T., and Bradley, D. (2005). A single amino acid converts a repressor to an activator of flowering. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 7748–7753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500932102

Hayama, R., Yokoi, S., Tamaki, S., Yano, M., and Shimamoto, K. (2003). Adaptation of photoperiodic control pathways produces short-day flowering in rice. Nature 422, 719–722. doi: 10.1038/Nature01549

Helliwell, C. A., Wood, C. C., Robertson, M., Peacock, W. J., and Dennis, E. S. (2006). The Arabidopsis FLC protein interacts directly in vivo with SOC1 and FT chromatin and is part of a high-molecular-weight protein complex. Plant J. 46, 183–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02686.x

Heo, J. B., and Sung, S. (2011). Vernalization-mediated epigenetic silencing by a long intronic noncoding RNA. Science 331, 76–79. doi: 10.1126/science.1197349

Ho, W. W. H., and Weigel, D. (2014). Structural features determining flower-promoting activity of Arabidopsis FLOWERING LOCUS T. Plant Cell 26, 552–564. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.115220

Hong, Y. P., Lin, S. Q., Jiang, Y. M., and Ashraf, M. (2008). Variation in contents of total phenolics and flavonoids and antioxidant activities in the leaves of 11 Eriobotrya Species. Plant Food. Hum. Nutr. 63, 200–204. doi: 10.1007/s11130-008-0088-6

Hou, X. L., Zhou, J. N., Liu, C., Liu, L., Shen, L. S., and Yu, H. (2014). Nuclear factor Y-mediated H3K27me3 demethylation of the SOC1 locus orchestrates flowering responses of Arabidopsis. Nat. Commun. 5:4601. doi: 10.1038/Ncomms5601

Hsu, C. Y., Adams, J. P., Kim, H. J., No, K., Ma, C. P., Strauss, S. H., et al. (2011). FLOWERING LOCUS T duplication coordinates reproductive and vegetative growth in perennial poplar. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 10756–10761. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104713108

Hsu, C. Y., Liu, Y. X., Luthe, D. S., and Yuceer, C. (2006). Poplar FT2 shortens the juvenile phase and promotes seasonal flowering. Plant Cell 18, 1846–1861. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.041038

Huang, N. C., Jane, W. N., Chen, J., and Yu, T. S. (2012). Arabidopsis thaliana CENTRORADIALIS homologue (ATC) acts systemically to inhibit floral initiation in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 72, 175–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.05076.x

Jang, S., Torti, S., and Coupland, G. (2009). Genetic and spatial interactions between FT. TSF and SVP during the early stages of floral induction in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 60, 614–625. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03986.x

Kim, W., Park, T. I., Yoo, S. J., Jun, A. R., and Ahn, J. H. (2013). Generation and analysis of a complete mutant set for the Arabidopsis FT/TFL1 family shows specific effects on thermo-sensitive flowering regulation. J. Exp. Bot. 64, 1715–1729. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert036

Kinoshita, T., Ono, N., Hayashi, Y., Morimoto, S., Nakamura, S., Soda, M., et al. (2011). FLOWERING LOCUS T regulates stomatal opening. Curr. Biol. 21, 1232–1238. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.06.025

Kotoda, N., Hayashi, H., Suzuki, M., Igarashi, M., Hatsuyama, Y., Kidou, S., et al. (2010). Molecular characterization of FLOWERING LOCUS T-like genes of apple (Malus × domestica Borkh.). Plant Cell Physiol. 51, 561–575. doi: 10.1093/Pcp/Pcq021

Krieger, U., Lippman, Z. B., and Zamir, D. (2010). The flowering gene SINGLE FLOWER TRUSS drives heterosis for yield in tomato. Nat. Genet. 42, 459–463. doi: 10.1038/Ng.550

Kumar, S. V., Lucyshyn, D., Jaeger, K. E., Alos, E., Alvey, E., Harberd, N. P., et al. (2012). Transcription factor PIF4 controls the thermosensory activation of flowering. Nature 484, 242–245. doi: 10.1038/Nature10928

Lee, J. H., Ryu, H. S., Chung, K. S., Pose, D., Kim, S., Schmid, M., et al. (2013). Regulation of temperature-responsive flowering by MADS-Box transcription factor repressors. Science 342, 628–632. doi: 10.1126/science.1241097

Lee, L. Y. C., Hou, X. L., Fang, L., Fan, S. G., Kumar, P. P., and Yu, H. (2012). STUNTED mediates the control of cell proliferation by GA in Arabidopsis. Development 139, 1568–1576. doi: 10.1242/dev.079426

Lifschitz, E., and Eshed, Y. (2006). Universal florigenic signals triggered by FT homologues regulate growth and flowering cycles in perennial day-neutral tomato. J. Exp. Bot. 57, 3405–3414. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erl106

Lin, S. Q. (2007). World loquat production and research with special reference to China. Acta. Hortic. 750, 37–44. doi: 10.17660/ActaHortic.2007.750.2

Lin, S. Q., Sharpe, R. H., and Janick, J. (1999). “Loquat: botany and horticulture,” in Horticultural Reviews, ed. J. Janick (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell), 233–276.

Liu, L., Zhu, Y., Shen, L. S., and Yu, H. (2013a). Emerging insights into florigen transport. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 16, 607–613. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2013.06.001

Liu, Y. X., Song, H. W., Liu, Z. L., Hu, G. B., and Lin, S. Q. (2013b). Molecular characterization of loquat EjAP1 gene in relation to flowering. Plant Growth Regul. 70, 287–296. doi: 10.1007/s10725-013-9800-0

Matsoukas, I. G., Massiah, A. J., and Thomas, B. (2012). Florigenic and antiflorigenic signaling in plants. Plant Cell Physiol. 53, 1827–1842. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcs130

Mimida, N., Kidou, S. I., Lwanami, H., Moriya, S., Abe, K., Voogd, C., et al. (2011). Apple FLOWERING LOCUS T proteins interact with transcription factors implicated in cell growth and organ development. Tree Physiol. 31, 555–566. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpr028

Mouhu, K., Hytonen, T., Folta, K., Rantanen, M., Paulin, L., Auvinen, P., et al. (2009). Identification of flowering genes in strawberry, a perennial SD plant. BMC Plant Biol. 9:122. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-9-122

Navarro, C., Abelenda, J. A., Cruz-Oro, E., Cuellar, C. A., Tamaki, S., Silva, J., et al. (2011). Control of flowering and storage organ formation in potato by FLOWERING LOCUS T. Nature 478, 119–122. doi: 10.1038/Nature10431

Nishikawa, F., Endo, T., Shimada, T., Fujii, H., Shimizu, T., Omura, M., et al. (2007). Increased CiFT abundance in the stem correlates with floral induction by low temperature in Satsuma mandarin (Citrus unshiu Marc.). J. Exp. Bot. 58, 3915–3927. doi: 10.1093/Jxb/Erm246

Pennisi, E. (2007). Plant science - Long-sought plant flowering signal unmasked, again. Science 316, 350–351. doi: 10.1126/science.316.5823.350

Pin, P. A., Benlloch, R., Bonnet, D., Wremerth-Weich, E., Kraft, T., Gielen, J. J. L., et al. (2010). An antagonistic pair of FT homologs mediates the control of flowering time in sugar beet. Science 330, 1397–1400. doi: 10.1126/science.1197004

Pin, P. A., and Nilsson, O. (2012). The multifaceted roles of FLOWERING LOCUS T in plant development. Plant Cell Environ. 35, 1742–1755. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2012.02558.x

Pnueli, L., Gutfinger, T., Hareven, D., Ben-Naim, O., Ron, N., Adir, N., et al. (2001). Tomato SP-interacting proteins define a conserved signaling system that regulates shoot architecture and flowering. Plant Cell 13, 2687–2702. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010293

Pose, D., Verhage, L., Ott, F., Yant, L., Mathieu, J., Angenent, G. C., et al. (2013). Temperature-dependent regulation of flowering by antagonistic FLM variants. Nature 503, 414–417. doi: 10.1038/Nature12633

Randoux, M., Daviere, J. M., Jeauffre, J., Thouroude, T., Pierre, S., Toualbia, Y., et al. (2014). RoKSN, a floral repressor, forms protein complexes with RoFD and RoFT to regulate vegetative and reproductive development in rose. New Phytol. 202, 161–173. doi: 10.1111/nph.12625

Song, J., Angel, A., Howard, M., and Dean, C. (2012). Vernalization - a cold-induced epigenetic switch. J. Cell Sci. 125, 3723–3731. doi: 10.1242/Jcs.084764

Song, Y. H., Ito, S., and Imaizumi, T. (2013). Flowering time regulation: photoperiod- and temperature-sensing in leaves. Trends Plant Sci. 18, 575–583. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2013.05.003

Sparkes, I. A., Runions, J., Kearns, A., and Hawes, C. (2006). Rapid, transient expression of fluorescent fusion proteins in tobacco plants and generation of stably transformed plants. Nat. Protoc. 1, 2019–2025. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.286

Sussmilch, F. C., Berbel, A., Hecht, V., Vander Schoor, J. K., Ferrandiz, C., Madueno, F., et al. (2015). Pea VEGETATIVE2 is an FD homolog that is essential for flowering and compound inflorescence development. Plant Cell 27, 1046–1060. doi: 10.1105/tpc.115.136150

Swiezewski, S., Liu, F. Q., Magusin, A., and Dean, C. (2009). Cold-induced silencing by long antisense transcripts of an Arabidopsis polycomb target. Nature 462, 799–802. doi: 10.1038/nature08618

Tiwari, S. B., Shen, Y., Chang, H. C., Hou, Y. L., Harris, A., Ma, S. F., et al. (2010). The flowering time regulator CONSTANS is recruited to the FLOWERING LOCUS T promoter via a unique cis-element. New Phytol. 187, 57–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03251.x

Tsuji, H., Nakamura, H., Taoka, K., and Shimamoto, K. (2013). Functional diversification of FD transcription factors in rice, components of florigen activation complexes. Plant Cell Physiol. 54, 385–397. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pct005

Turck, F., Fornara, F., and Coupland, G. (2008). Regulation and identity of florigen: FLOWERING LOCUS T moves center stage. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 59, 573–594. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092755

Tylewicz, S., Tsuji, H., Miskolczi, P., Petterle, A., Azeez, A., Jonsson, K., et al. (2015). Dual role of tree florigen activation complex component FD in photoperiodic growth control and adaptive response pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 3140–3145. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1423440112

Varkonyi-Gasic, E., Moss, S. M. A., Voogd, C., Wang, T. C., Putterill, J., and Hellens, R. P. (2013). Homologs of FT, CEN and FD respond to developmental and environmental signals affecting growth and flowering in the perennial vine kiwifruit. New Phytol. 198, 732–746. doi: 10.1111/Nph.12162

Wellmer, F., and Riechmann, J. L. (2010). Gene networks controlling the initiation of flower development. Trends Genet. 26, 519–527. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2010.09.001

Wenkel, S., Turck, F., Singer, K., Gissot, L., Le Gourrierec, J., Samach, A., et al. (2006). CONSTANS and the CCAAT box binding complex share a functionally important domain and interact to regulate flowering of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 18, 2971–2984. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.043299

Wickland, D. P., and Hanzawa, Y. (2015). The FLOWERING LOCUS T/TERMINAL FLOWER 1 gene family: functional evolution and molecular mechanisms. Mol. Plant 8, 983–997. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2015.01.007

Wigge, P. A., Kim, M. C., Jaeger, K. E., Busch, W., Schmid, M., Lohmann, J. U., et al. (2005). Integration of spatial and temporal information during floral induction in Arabidopsis. Science 309, 1056–1059. doi: 10.1126/science.1114358

Yan, Y. Y., Shen, L. S., Chen, Y., Bao, S. J., Thong, Z. H., and Yu, H. (2014). A MYB-domain protein EFM mediates flowering responses to environmental cues in Arabidopsis. Dev. Cell 30, 437–448. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.07.004

Yoo, S. J., Chung, K. S., Jung, S. H., Yoo, S. Y., Lee, J. S., and Ahn, J. H. (2010). BROTHER OF FT AND TFL1 (BFT) has TFL1-like activity and functions redundantly with TFL1 in inflorescence meristem development in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 63, 241–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04234.x

Keywords: loquat, flowering, floral transition, FT, FD

Citation: Zhang L, Yu H, Lin S and Gao Y (2016) Molecular Characterization of FT and FD Homologs from Eriobotrya deflexa Nakai forma koshunensis. Front. Plant Sci. 7:8. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00008

Received: 20 October 2015; Accepted: 07 January 2016;

Published: 22 January 2016.

Edited by:

Anna Maria Mastrangelo, CRA-Centro di Ricerca per la Cerealicoltura, ItalyReviewed by:

Li-Song Chen, Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, ChinaEnrico Francia, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Italy

Copyright © 2016 Zhang, Yu, Lin and Gao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shunquan Lin, loquat@scau.edu.cn; Yongshun Gao, yongshungao@163.com

Ling Zhang

Ling Zhang Hao Yu

Hao Yu Shunquan Lin

Shunquan Lin Yongshun Gao

Yongshun Gao