- Psychiatry/Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA, USA

This study evaluated parents’ experience with University of Massachusetts (UMass) Child Psychiatry Access Project (MCPAP), a consultation service to primary care providers (PCP), aimed at improving access to child psychiatry. Parent satisfaction questionnaire was sent to families referred to UMass MCPAP by their PCP, asking about their concerns leading to the referral, the satisfaction from the service provided, adequacy of the follow up plan, and outcome. Seventy-nine percent of parents agreed or strongly agreed that the services provided were offered in a timely manner. Fifty percent agreed or strongly agreed that their child’s situation improved following their contact with the services. Sixty-nine percent agreed or strongly agreed that the service met their family’s need. The results suggest moderate to high parental satisfaction with MCPAP model, but highlight ongoing challenges in making successful referrals for children’s mental health services in the community, following MCPAP recommendations.

Introduction

“Many barriers remain that prevent children, teenagers, and their parents from seeking help from the small number of specially trained professionals…. This places a burden on pediatricians, family physicians, and other gatekeepers to identify children for referral and treatment decisions (US Department of Health and Human Services, 1999).”

Prevalence and Magnitude of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Problems

Approximately one in five children and adolescents (15 million) meet criteria for a psychiatric disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) during the course of a year (US Department of Health and Human Services, 1999), and between 15 and 25% of children and adolescents seen in pediatric primary care have a behavioral health disorder with significant psychopathology, high functional impairment, and frequent psychiatric diagnostic co-morbidity (Lahey et al., 1996; Wildman et al., 1997; Cassidy and Jellinek, 1998; Connor et al., 2006; Guevara et al., 2007; Merikangas et al., 2010). The majority of individuals suffering from mental disorders experience the onset of a disorder before adulthood, yet most affected children receive inadequate treatment or no treatment at all (Kelleher et al., 2006). Less than 20% of children meeting criteria for psychiatric disorder are referred for mental health services (US Department of Health and Human Services, 1999; Lavigne et al., 2008), and only a small fraction of them receive evaluation and treatment by a mental health professional. Because child psychiatry services are frequently unavailable, or because of other barriers to accessing mental health care, primary care clinicians are frequently left managing these children without access to child psychiatry consultation (Connor et al., 2006).

The number of children with recognized behavioral problems in primary care may be increasing as a result of increasing recognition of mental health disorders in children, reduced stigma, treatment acceptance by families, a greater array of therapies to manage these problems, and increases in poverty and other risk factors for mental illness (Guevara et al., 2007). Pediatric clinicians are increasingly embracing this challenge, as evidenced by rapidly growing rates of mandatory screening, diagnosis, and treatment during primary care visits. As many as one third of children identified and treated for mental health problems receive outpatient mental healthcare from primary care providers (PCP) (Ringeisen et al., 2002). Nevertheless, four out of five children with diagnosable behavioral and emotional problems are not identified by their pediatricians, and even fewer receive mental health services (Cassidy and Jellinek, 1998).

In a survey of pediatricians who work in a primary care setting, pediatricians estimated that on average 15% of children seen in their practice are treated for behavioral health disorders, and reported that they frequently provide both pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments to children and adolescents with mild to moderate behavioral health disorders, but not for severe disorders (Williams et al., 2004). Most pediatricians agree that greater collaborations with mental health providers would improve pediatric assessment of behavioral health disorders (Banh et al., 2008), and suggest that primary care and mental health clinicians may benefit from collaborating on treatment plans (Guevara et al., 2007). Although many barriers exist, pediatric primary care health systems will continue to play an important role in the identification and treatment of mental disorders in children, as well as help integrate approaches to physical and mental health (Ringeisen et al., 2002).

Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Project

Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Project (MCPAP) is a Consultation Liaison model, aimed at improving access to child psychiatry for families through consultation to PCPs throughout the Commonwealth. Consultations to PCPs are done either by phone contact and/or by a direct evaluation of the child by a MCPAP clinician. MCPAP grew out of a federally funded pilot program Targeted Child Psychiatric Services (Connor et al., 2006). Since June 2004, the Massachusetts Behavioral Health Partnership (MBHP), a behavioral health Managed Care Organization (MCO), has administered the service throughout the Commonwealth on an insurance blind basis. There are six regional teams located in academic medical centers, consisting of a child psychiatrist, social worker/psychologist, and a care coordinator who provide the service through contracts with MBHP. PCPs in the region enroll and are provided with Monday through Friday, nine to five, telephone consultation within 30 min of request. This consultation by a child clinician/psychiatrist results in either: answer to PCP’s question, referral to care coordinator, referral to team therapist for transitional support, or referral for a face to face diagnostic or psychopharmacologic consultation. MCPAP has achieved recognition as an innovative, effective model for providing child psychiatry consultation to Primary Care Pediatricians. A survey of PCPs conducted by MBHP found that physicians found these consultations to be useful and that there was an increased ability to meet the needs of their patients with psychiatric problems (Sarvet et al., 2010). However, most providers surveyed still felt that overall access to children’s mental health services was not adequate. While this study indicated that pediatric PCPs were satisfied with this consultation program, no systemic data has been obtained regarding parent satisfaction with MCPAP. As a model, MCPAP appears to be a promising strategy to meet the growing demand for children’s mental health services. Knowledge of the parent perspective of this type of model provides a further assessment of its usefulness as a non-stigmatizing and potentially better way to support early identification and treatment of the mental health needs of children and youth.

Parent Satisfaction

Parent satisfaction with services is an important component in evaluating their adequacy, as parents are usually responsible for obtaining services for their child and are important to the success of treatment through their participation. Parent participation in treatment is crucial to its success, and is related to continuation of treatment at home when services are completed. (Gerkensmeyer and Austin, 2005; Gerkensmeyer et al., 2006). Parent satisfaction with services is affected by the difference between families’ expectations of care and their actual experience of care. Expectations are formed through a combination of prior health care experience, background, the child’s needs, the parent’s need and resources, and the impact of the child’s issues on the parents (Wood et al., 2009). The field of child and adolescent mental health is moving in the direction of care that is individualized, strength-based, coordinated, culturally competent, and driven by the child and family’s goals and decision making, including program evaluation. Increasingly, child and adolescent behavioral health interventions focus on parent involvement and seek parental direction in the development of treatment plans. This is emphasized in the guiding principles of the Child and Adolescent Service Systems Program (CASSP) under the auspices of the National Institutes of Mental Health (NIMH; Winters and Metz, 2009).

Rey et al. (1999), conducted a 4-year study in New South Wales, Australia, examining parent satisfaction and outcome in a child and adolescent mental health service. Eighty percent of referrals to Rivendell clinic were tertiary patients, referred for consultation or advice and subsequently returned to local services for further treatment. Satisfaction was measured using a modified parent satisfaction questionnaire (PSQ), which was mailed to eligible patients. The questionnaire had eight items rated on a four-point scale, and included questions about further use of services and asked for specific comments. Satisfaction questionnaires were returned by 40% of parents; 76% of these were mostly or very satisfied. Satisfaction scores increased with the number of outpatient sessions attended but did not differ between inpatients and outpatients. Two weaknesses described in this study were low response rates (60% of the patients did not return PSQs) and that questionnaires need to inquire specifically about aspects of care that parents consider important. This study did not use any incentives or any follow up contact with non-responders (Rey et al., 1999).

Stallard (1995, 1996) describes the validity and reliability of the PSQ as well as differences between responders and non-responders to postal questionnaires. The response rate reported for this postal mailing questionnaire was 55%, and non-responders were significantly more likely to have had fewer appointments and more likely to have dropped out of services. Non-responders as compared to those who did respond were also less satisfied with services (although this difference was not statistically significant; Stallard, 1995, 1996).

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to evaluate parents’ experience with University of Massachusetts (UMass) MCPAP, as parent satisfaction with services is an important component in evaluating service adequacy. The authors hoped to gain a better understanding of the specific needs of families referred to a Child Psychiatry consultation service and learn what aspects of the model are helpful as well as what aspects need improvement.

In addition to assessing parent satisfaction, this study attempted to answer three main questions;

(1) What are the characteristics of the children and families served by MCPAP?

(2) What type of services did children receive and how satisfied were caregivers with those services?

(3) In what ways could services be improved?

Materials and Methods

University of Massachusetts Medical School Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained for this study. A PSQ was sent to all families referred to UMass MCPAP between 2/2008 and 2/2009. Parents of youth referred for consultation were identified using the University of Massachusetts Medical Center (UMMHC) database. Responses were anonymous and returning the questionnaire was considered as consent to participate in this study. The initial mailing occurred 4–6 weeks after enrollment in MCPAP services to allow enough time between evaluation and referral services, for parents to gage the impact of the services provided. A $2.00 stipend and a stamped-return envelope were provided with each questionnaire. The initial mailing was followed by a reminder letter to all families with a second copy of the questionnaire sent within 3–4 weeks. Finally, a thank you note was sent to all families.

Parent Satisfaction Questionnaire Design

MCPAP PSQ is a three-page questionnaire created by the research team that was reviewed with caregivers of children with emotional and behavioral challenges during its development to ensure that questions were understandable and meaningful. Both five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) and open ended response questions were used. The PSQ included the following:

Demographics

The demographics questions asked about child and parental age, gender and race/ethnicity, household income, and parent’s education. Information regarding the child’s diagnosis was requested under this section.

Parental perception of services

Parents were asked six open ended and yes/no questions to assess their concerns leading to the referral and referral process for MCPAP services. Likert scale items included 11 items assessing parent’s general satisfaction with the MCPAP services and six items measuring parent satisfaction with the evaluation process by MCPAP psychiatrist/psychiatric nurse clinician. If parents had contact with MCPAP social worker they were asked about their satisfaction with the services provided.

Follow up services in the community

Four items measured parent’s satisfaction with the follow up and mental health referral process on a five-point Likert scale. Further questions regarding follow up in the community asked about family’s engagement with the services they were referred to, and the reasons for success or failure of this engagement.

Qualitative open ended questions

Finally, parents were asked to briefly describe what they were most satisfied with, least satisfied with, and any suggestions for improvement.

Overall mean satisfaction

An overall satisfaction score was calculated by creating a mean of the 22 Likert items included in PSQ measuring general satisfaction with services, satisfaction with the evaluation process, and satisfaction with the follow up and mental health referral process. Internal reliability for this summary score was excellent (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.983).

Data Analysis

Descriptive analyses (frequencies and percents or means and SD) were conducted to provide information on all variables of interest (child and family characteristics, responses to satisfaction questions). Follow up analyses were then used to explore factors that may be related to overall satisfaction. For these analyses, t-tests were used to examine group differences in the overall mean satisfaction score and Pearson product-moment correlations were used to explore the relationship between mean satisfaction with services and two other variables: (1) how long the child had experienced problems before their MCPAP visit, and (2) length of time between referral to MCPAP and first contact with the MCPAP team.

Results

Characteristics of Children and Families

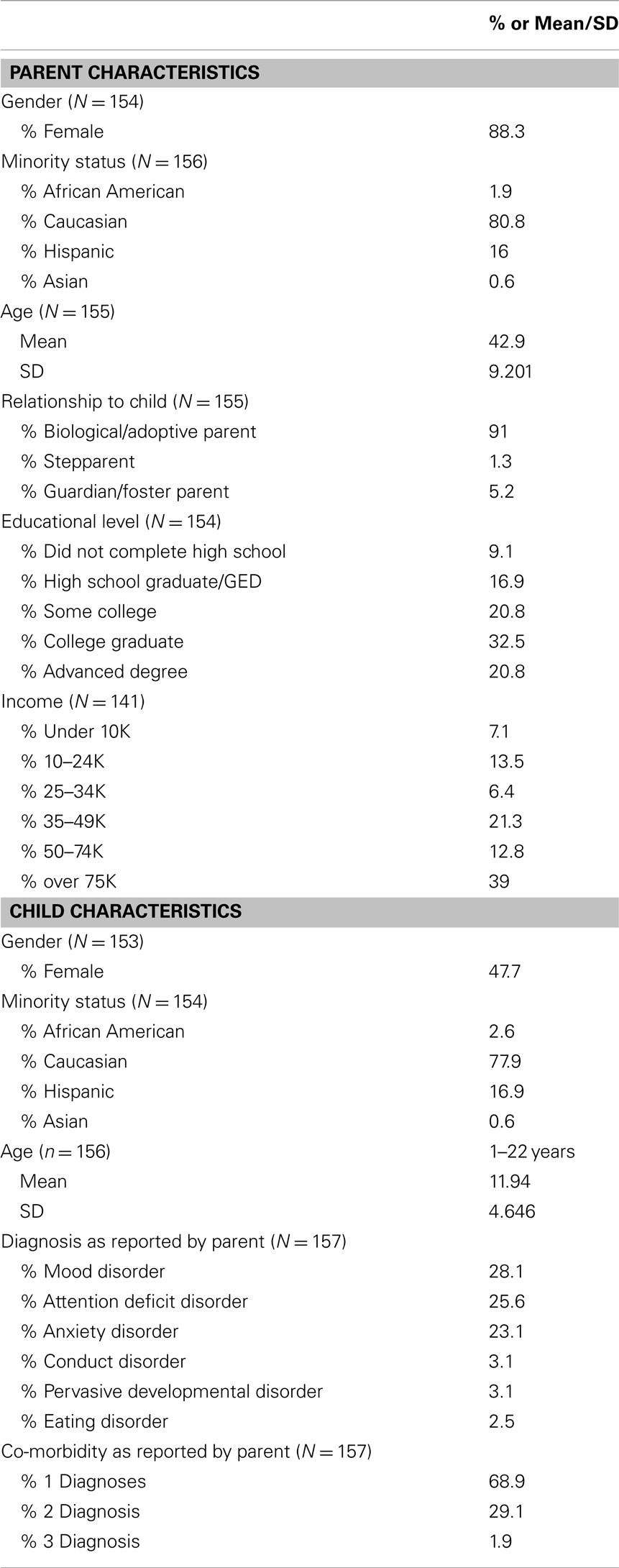

Three hundred sixty PSQs were mailed, and 158 PSQs returned, defining a response rate of 44%. Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of responding parents and their children. Most parents were female, Caucasian, and college educated. Approximately 52% of families had an annual income of $50,000 or above. The majority of referred children were Caucasian with almost equal numbers of boys and girls, and an average age of 12 years. Most were reported to have one diagnosis, although a sizeable minority (about 30%) had two or more diagnoses. The most frequently reported diagnostic categories included mood disorders, attention deficit disorders, and anxiety disorders. The length of time that child had the presenting problem ranged from 1 month to 11 years, with a mean of 2.83 years.

Services and Satisfaction

The reported time between referral to MCPAP team and the first telephonic contact with MCPAP was relatively short: 25.9% less than a week, 50.3% between 1 and 3 weeks, 10.5% between 3 and 4 weeks, 11.9% more than 4 weeks. Seventy-five percent of families did not have a face to face visit with a MCPAP clinician, while 25% had a visit with a MCPAP clinician. In terms of the follow up that was offered in the community after contact with MCPAP, 13.7% of parents reported that the time between referral and follow up was less than a week, 43.2% between 1 and 3 weeks, 13.7% between 3 and 4 weeks, 29.5% more than 4 weeks. Eighty-four percent were able to get to a follow up appointment in the community, while 14.1% were unable to get to an appointment. The mean number of appointments attended in the community was reportedly 4.2 (SD = 7.542), and 60.4% of families were still engaged with their community provider at the time of completing the PSQ. Ninety percent of children have not experienced an out of home placement since their contact with MCPAP, while 9.4% have experienced an out of home placement.

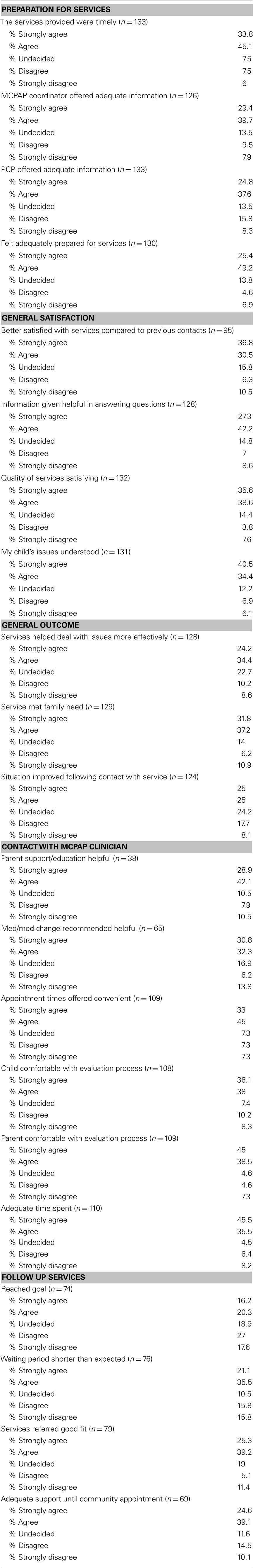

Table 2 shows parent responses to the satisfaction items on the PSQ. Most (78.9%) of parents agreed or strongly agreed that the services provided were offered in a timely manner, and most 74.9% also agreed or strongly agreed with the statement that their child’s issues were understood. Half of parents agreed or strongly agreed that their child’s situation improved following their contact with the services. About three quarters (74.2%) agreed or strongly agreed that the quality of the service they received was satisfying and that the service met their family’s need (69%). Over half of parents (58.6%) agreed or strongly agreed that the service helped them deal with their issues more effectively. Finally, more than two thirds (67.3%) also agreed or strongly agreed that they were better satisfied with the service compared to previous contact with mental health providers for their child.

Analysis of group differences and factors related to satisfaction

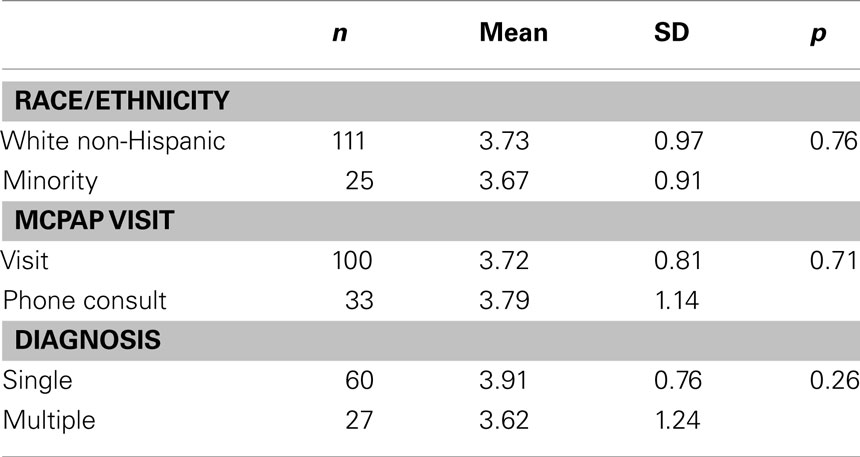

Follow up analyses were conducted to assess whether there were differences in satisfaction between minority/non-minority families, those who had a visit with the MCPAP clinician versus those who did not, and those with single versus multiple diagnoses. Results of these t-tests revealed no significant group differences in satisfaction by minority status, visit status, or co-morbidity status (see Table 3). Correlation analysis also showed no significant relation between length of time the child had been experiencing problems and satisfaction with MCPAP services (n = 129; r = −0.016; p = n.s.) or between satisfaction with services and how long the parent had to wait before being contacted by the MCPAP team after referral (n = 131; r = −0.008; p = n.s.).

Qualitative results

Parent satisfaction questionnaire also asked parents about the aspects of the program with which they were most satisfied. The following quotes are representative of recurring themes, of families experiencing MCPAP services as a starting point to navigate the child mental health system in an effective way: “Someone finally listening and helping me to set up services that I was previously denied or unaware of,” “The program in general – to have a starting point in my search for help,” “Phone support to primary care physician was excellent,” “The interview process was very calming,” “We felt so good with the interviewer,” “The follow up from the nurse for referring us to a psychiatrist was key,” “Compared to other psychiatric referrals, MCPAP’s influence on getting a psychiatrist appointment was better than the rest,” and “That we would have direct access to someone who could suggest a diagnosis on the day of appointment.”

Families were also asked about aspects of the program with which they were least satisfied, and their replies highlighted the difficulties in obtaining follow up treatment in the community, when that was recommended by MCPAP: “The 3-month wait between calling for an appointment and the appointment date – far too long for a family/teen in crisis with the onset of a mental illness,” and “The scarcity of child psychiatrists to prescribe medications.”

Discussion

The results suggest moderate to high parent satisfaction rates with MCPAP services and no group differences that would suggest that MCPAP works better for some populations than others. Notable are the high rates of parents reporting they felt prepared, heard, and understood. Parents were also highly satisfied with the face to face contact they had with MCPAP clinicians, when that contact had occurred. This compares favorably to studies of parent satisfaction with mental health services treatment (Stallard, 1995; Rey et al., 1999; Gerkensmeyer et al., 2006). Parents reported being less satisfied with regard to the delay in getting to follow up appointments in the community and with reaching their goals for their child. For instance, approximately 76% of families were able to see their MCPAP clinician within 3 weeks of referral and only approximately 12% had to wait more than a month. In comparison, only 57% of families were able to see a clinician in the community within 3 weeks of referral while 30% had to wait more than a month. Qualitative follow up responses confirm parent dissatisfaction with wait times in the community. In conclusion, while most parents felt that the quality of the services they received was satisfying, only half thought their child’s situation improved following the contact, emphasizing the ongoing need for timely and appropriate follow up care in the community and the complexity of resolving a long term problem with a short term intervention. As this is a challenge that will likely need to be addressed in a multisystemic way, it may be prudent to create a structure that educates parents ahead of time about these challenges to help reframe their expectations.

Our findings should be understood in terms of a low response rate of around 40%, although this does fall within the range of studies on this topic. It is possible that higher rates could be achieved by repeated mention of the survey at each MCPAP contact, however there are inherent challenges in conducting such a study related to families mobility and other factors. Some questions had lower responses rates (see Table 2), primarily questions regarding parent satisfaction with contact with MCPAP clinician and follow up services. These numbers can be understood by the fact that these questions were only answered by parents who received these services as part of their family’s contact with MCPAP. Finally, this study focused primarily on parent satisfaction with the UMASS MCPAP program and did not include other MCPAP sites. This suggests the possibility of a study selection bias and the data might therefore not be generalizable to all programs. Nevertheless, we believe that lessons can be learned from these results.

Implications for Behavioral Health

As a model, MCPAP was designed to support pediatric PCPs and address the lack of access to child psychiatry. This paper demonstrates that parents feel comfortable and supported with this ambulatory consultation liaison model. Providing phone back up and real time face to face diagnostic evaluations and treatment plans appears to be an effective way to help PCPs deal with the increasing behavioral health needs of their pediatric patients. Support from MCPAP to families to find follow up services in the community was especially valued. Both the consultative aspect of this model and the case management service which links families with follow up services in the community can be implemented in other states. The results show high parental satisfaction with MCPAP evaluation process, but also highlight the need for appropriate mental health follow up in the community in order to help children and families reach their goals.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edn. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Banh, M. K., Saxe, G., Mangione, T., and Horton, N. J. (2008). Physician-reported practice of managing childhood posttraumatic stress in pediatric primary care. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 30, 536–545.

Cassidy, L. J., and Jellinek, M. S. (1998). Approaches to recognition and management of childhood psychiatric disorders in pediatric primary care. Pediatr. Clin. North Am. 45, 1037–1052.

Connor, D. F., McLaughlin, T. J., Jeffers-Terry, M., O’Brien, W. H., Stille, C. J., Young, L. M., and Antonelli, R. C. (2006). Targeted child psychiatric services: a new model of pediatric primary clinician – child psychiatry collaborative care. Clin. Pediatr. (Phila.) 45, 423–434.

Gerkensmeyer, J. E., and Austin, J. K. (2005). Development and testing of a scale measuring parent satisfaction with staff interactions. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 32, 61–73.

Gerkensmeyer, J. E., Austin, J. K., and Miller, T. K. (2006). Model testing: examining parent satisfaction. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 20, 65–75.

Guevara, J. P., Rothbard, A., Shera, D., Zhao, H., Forrest, C. B., Kelleher, K., and Schwarz, D. (2007). Correlates of behavioral care management strategies used by primary care pediatric providers. Ambul. Pediatr. 7, 160–166.

Kelleher, K. J., Campo, J. V., and Gardner, W. P. (2006). Management of pediatric mental disorders in primary care: where are we now and where are we going? Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 18, 649–653.

Lahey, B. B., Flagg, E. W., Bird, H. R., Schwab-Stone, M. E., Canino, G., Dulcan, M. K., Leaf, P. J., Davies, M., Brogan, D., Bourdon, K., Horwitz, S. M., Rubio-Stipec, M., Freeman, D. H., Lichtman, J. H., Shaffer, D., Goodman, S. H., Narrow, W. E., Weissman, M. M., Kandel, D. B., Jensen, P. S., Richters, J. E., and Regier, D. A. (1996). The NIMH methods for the epidemiology of child and adolescent mental disorders (MECA) study: Background and methodology. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 35, 855–864.

Lavigne, J. V., Lebailly, S. A., Gouze, K. R., Cicchetti, C., Pochyly, J., Arend, R., Jessup, B. W., and Binns, H. J. (2008). Treating oppositional defiant disorder in primary care: a comparison of three models. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 33, 449–461.

Merikangas, K. R., He, J. P., Brody, D., Fisher, P. W., Bourdon, K., and Koretz, D. S. (2010). Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders among US children in the 2001–2004 NHANES. Pediatrics 125, 75–81.

Rey, J. M., Plapp, J. M., and Simpson, P. L. (1999). Parental satisfaction and outcome: a 4-year study in a child and adolescent mental health service. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 33, 22–28.

Ringeisen, H., Oliver, K. A., and Menvielle, E. (2002). Recognition and treatment of mental disorders in children: considerations for pediatric health systems. Paediatr. Drugs 4, 697–703.

Sarvet, B., Gold, J., Bostic, J. Q., Masek, B. J., Prince, J. B., Jeffers-Terry, M., Moore, C. F., Molbert, B., and Straus, J. H. (2010). Improving access to mental health care for children: the massachusetts child psychiatry access project. Pediatrics 126, 1191–1200.

Stallard, P. (1995). Parental satisfaction with intervention: differences between respondents and non-respondents to a postal questionnaire. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 34(Pt 3), 397–405.

Stallard, P. (1996). Validity and reliability of the parent satisfaction questionnaire. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 35(Pt 2), 311–318.

US Department of Health and Human Services. (1999). Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health.

Wildman, B. G., Kinsman, A. M., Logue, E., Dickey, D. J., and Smucker, W. D. (1997). Presentation and management of childhood psychosocial problems. J. Fam. Pract. 44, 77–84.

Williams, J., Klinepeter, K., Palmes, G., Pulley, A., and Foy, J. M. (2004). Diagnosis and treatment of behavioral health disorders in pediatric practice. Pediatrics 114, 601–606.

Winters, N. C., and Metz, W. P. (2009). The wraparound approach in systems of care. Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. 32, 135–151.

Wood, D. L., McCaskill, Q. E., Winterbauer, N., Jobli, E., Hou, T., Wludyka, P. S., Stowers, K., and Livingood, W. (2009). A multi-method assessment of satisfaction with services in the medical home by parents of children and youth with special health care needs (CYSHCN). Matern. Child Health J. 13, 5–17.

Keywords: child psychiatry, primary care, consultation liaison, parent satisfaction

Citation: Dvir Y, Wenz-Gross M, Jeffers-Terry M and Metz WP (2012) An assessment of satisfaction with ambulatory child psychiatry consultation services to primary care providers by parents of children with emotional and behavioral needs: the Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Project University of Massachusetts Parent Satisfaction Study. Front. Psychiatry 3:7. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2012.00007

Received: 05 October 2011; Accepted: 26 January 2012;

Published online: 13 February 2012.

Edited by:

Anne Glowinski, Washington University School of Medicine, USAReviewed by:

Natasha Marrus, St. Louis Children’s Hospital, USAElise M. Fallucco, Nemours Children’s Clinic, USA

Copyright: © 2012 Dvir, Wenz-Gross, Jeffers-Terry and Metz. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial License, which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in other forums, provided the original authors and source are credited.

*Correspondence: Yael Dvir, Psychiatry/Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, University of Massachusetts Medical School, 55 Lake Avenue North, Worcester, MA 01655, USA. e-mail: yael.dvir@umassmed.edu