- 1Department of Family Medicine, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Serdang, Malaysia

- 2Jeffrey Cheah School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Monash University Sunway Campus, Subang Jaya, Malaysia

- 3School of Primary Health Care, Monash University, Notting Hill, VIC, Australia

Introduction: Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) among people aged 60 years and above is a growing public health problem. Regular physical activity is one of the key elements in the management of T2DM. Recommendations suggest that older people with T2DM will benefit from regular physical activity for better disease control and delaying complications. Despite the known benefits, many remain sedentary. Hence, this review assessed interventions for promoting physical activity in persons aged 65 years and older with T2DM.

Methods: A literature search was conducted using Ovid MEDLINE, PubMed, EMBASE, SPORTDiscus, and CINAHL databases to retrieve articles published between January 2000 and December 2012. Randomized controlled trials and quasi-experimental designs comparing different strategies to increase physical activity level in persons aged 65 years and older with T2DM were included. The methodological quality of studies was assessed.

Results: Twenty-one eligible studies were reviewed, only six studies were rated as good quality and only one study specifically targeted persons aged 65 years and older. Personalized coaching, goal setting, peer support groups, use of technology, and physical activity monitors were proven to increase the level of physical activity. Incorporation of health behavior theories and follow-up supports also were successful strategies. However, the methodological quality and type of interventions promoting physical activity of the included studies in this review varied widely across the eligible studies.

Conclusion: Strategies that increased level of physical activity in persons with T2DM are evident but most studies focused on middle-aged persons and there was a lack of well-designed trials. Hence, more studies of satisfactory methodological quality with interventions promoting physical activity in older people are required.

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is one of the most common chronic non-communicable diseases (NCDs) in many countries especially in the developing countries (1). The prevalence continues to increase with changing lifestyles and increasing obesity affecting all ages including older people. Current estimates indicate a growing burden of T2DM worldwide, which is greatest among persons aged 60 years and older (2, 3). Therefore, an emphasis on the lifestyle interventions such as regular physical activity to offset the trends of the increasing prevalence of T2DM is imperative. Regular physical activity is one of the key elements in the management of T2DM, and evidence has shown that engaging in regular physical activity leads to better control of T2DM and delayed complications (4, 5). Increasingly, recommendations suggest older people will benefit from regular physical activity especially in the presence of chronic NCDs such as T2DM (4, 6–8). Despite the evident health benefits, many people with T2DM, especially older people, remain sedentary or inactive (9–13).

Previous systematic reviews have been conducted to evaluate interventions promoting physical activity (14–18) but none have focused specifically on increasing levels of physical activity in people with T2DM. Only one review focused on T2DM but the review evaluated the effects of exercise on T2DM parameters and not on strategies to increase levels of physical activity (8). Only one review focused on persons aged 65 years and older, which compared the effects of home based with centre based physical activity programs on participants’ health (15). This review, however, did not include persons with T2DM. Furthermore, these reviews found that most interventions promoting physical activity had short-term effectiveness with several methodological weaknesses. To the best of our knowledge, no systematic review has been conducted evaluating interventions promoting physical activity in older people with T2DM. This review provides a qualitative evaluation of interventions promoting physical activity in older people with T2DM.

Methods

A systematic review using a qualitative synthesis method was conducted to retrieve and review the findings of previous literature on interventions promoting physical activity in older people (aged 65 years and over) with T2DM. In this review, changes in physical activity level was selected as the outcome variable instead of changes in exercise level, as exercise is a subset of physical activity. Physical activity is defined as “body movement that is produced by the contraction of skeletal muscles and that increases energy expenditure,” while exercise is “a planned, structured, and repetitive movement to improve or maintain one or more components of physical activity” (p.1511) (6).

Data Sources and Search Strategy

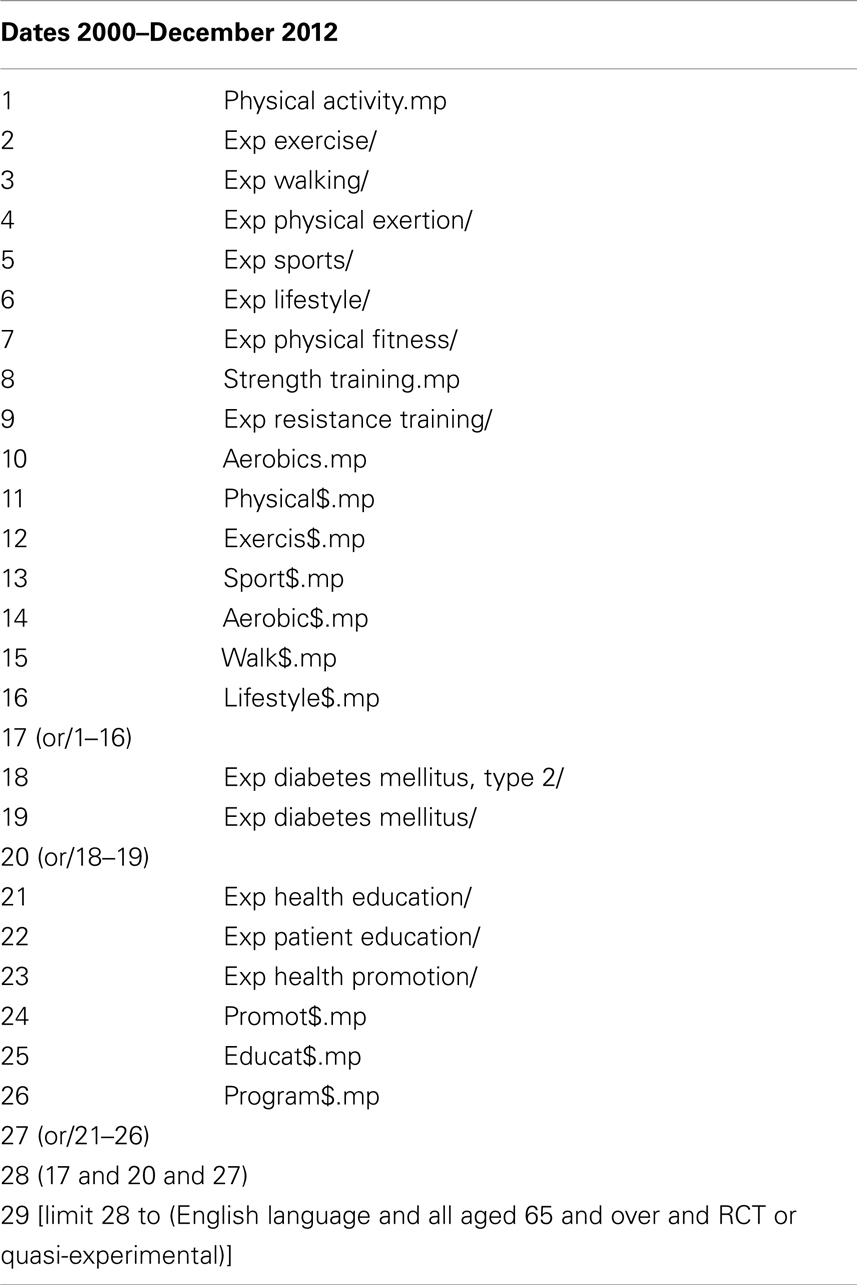

The search was conducted electronically according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (19) using the following databases: Ovid MEDLINE, PubMed, EMBASE, SPORTDiscus, and CINAHL. The Medical Subject Heading terms used in Ovid MEDLINE were adapted from Foster et al. (18) as presented in Table 1. Comparable searches were made for the other databases.

Only peer-reviewed published articles between years 2000 and end of December 2012 were used. No published reviews articles on physical activity were included but were used as a source of randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The reference lists of review articles and included studies were hand searched for other potentially eligible studies. Only articles published in English language were considered due to limited resources for translation. No attempts were made to contact authors for additional information, but cross-referencing on related previously published studies was performed to obtain additional information. All the titles, abstracts, and full-text of every study retrieved from the search were initially screened by one reviewer (Shariff-Ghazali Sazlina) using a standardized form with the eligibility criteria. A second reviewer (Shajahan Yasin) assessed the retrieved study if the first reviewer was in doubt on the paper’s eligibility.

Study Selection

All RCTs and quasi-experimental designs comparing different strategies to increase physical activity level in older people with T2DM were considered in this review. Studies that included self-management of diabetes and combined lifestyle (diet and physical activity) were also included. Studies with those aged 65 years and older with T2DM and living in the community were considered for this review. Studies performed on people with type 1 diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance were excluded. However, studies reporting combined results for T2DM and impaired glucose tolerance were included if the analysis of these results are conducted separately. The interventions may include one or combination of: (1) one-to-one or group counseling or advice, (2) self-directed or prescribed physical activity, (3) supervised or unsupervised physical activity, (4) on-going face to face support, (5) telephone support, (6) written motivation support material, and (7) self-monitoring devices (pedometer/accelerometer).

Interventions conducted by one or combinations of providers (health care providers, exercise specialist, peer coaches/mentors, and/or community health worker) were considered. No restrictions were included on the type and contents of the control group. The interventions could be compared with no intervention control, attention control (receiving attention such as usual diabetes care matched to length of intervention) or minimal intervention control group. The primary outcome measures in the included studies were changes in physical activity level. Studies with changes in cardiovascular disease risk factors (blood pressure, anthropometric measurements) and biochemical markers (glycosylated hemoglobin, lipid profiles) related to T2DM also were included.

Data Extraction

The data and outcomes extracted from the included studies were not combined and re-analyzed due to the qualitative nature of this systematic review and the variability in the interventions used. Each full-text article retrieved was evaluated systematically and summarized according to previously suggested method (20). These included the study’s: (1) objective (on effectiveness of physical activity interventions), (2) targeted health behavior (physical activity, self-management, or combined physical activity and nutrition), (3) characteristics of the study (study design, participants’ age, behavioral theoretical model, and sample size), (4) contents of the intervention (intervention strategies, intervention provider, length of intervention, and follow-up contacts), (5) targeted outcome(s), and (6) major results.

Methodological Quality Assessment

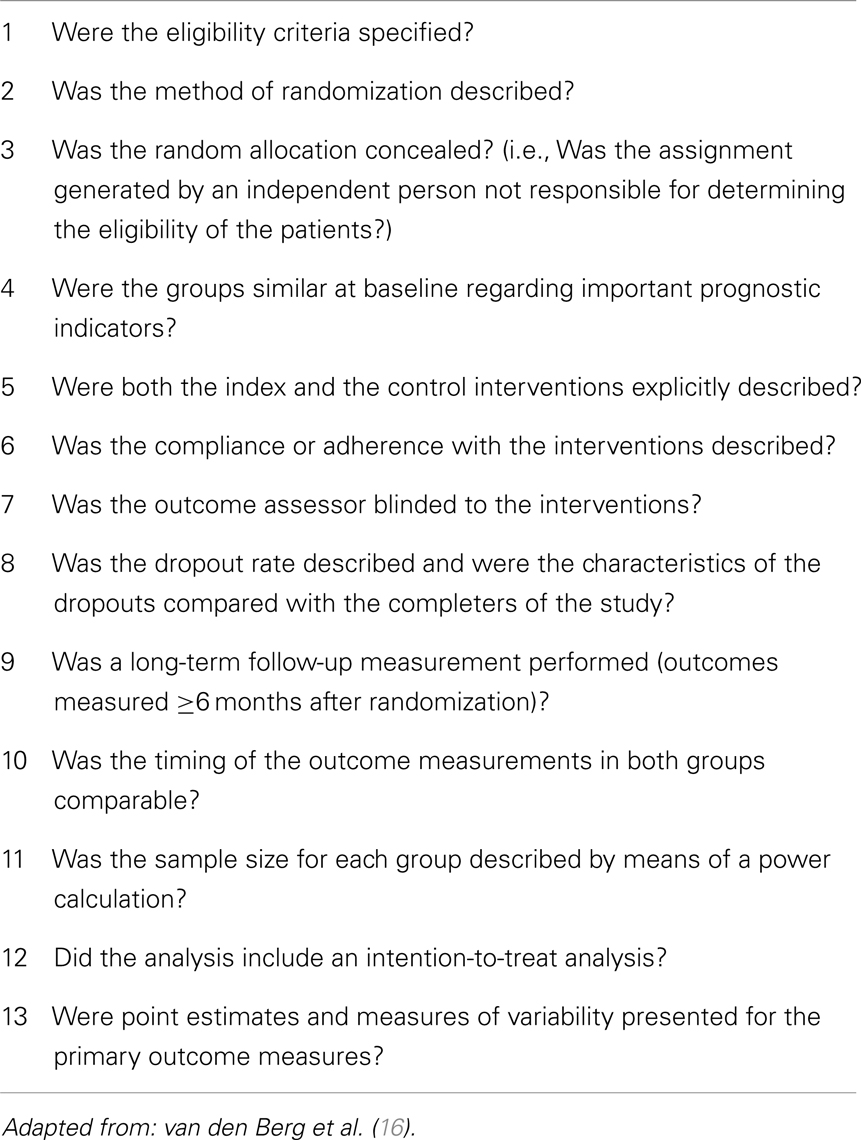

Each of the included studies was further evaluated for its methodological quality using a list of 13 criteria adopted from an internet-based physical activity interventions systematic review (16) (see Table 2), which was based on the Cochrane Collaboration Back Review Group guidelines (21). The score to indicate good methodological quality was adopted from van den Berg et al. as there is no existing guideline on the cut-offs to rate methodological quality (16). All criteria were scored as “yes,” “no,” or “unclear” and resulting in a summary score between 0 and 13. A good methodological quality of study is considered if two thirds or more of the criteria are fulfilled, which is a summary score of 9 or higher (16).

Results

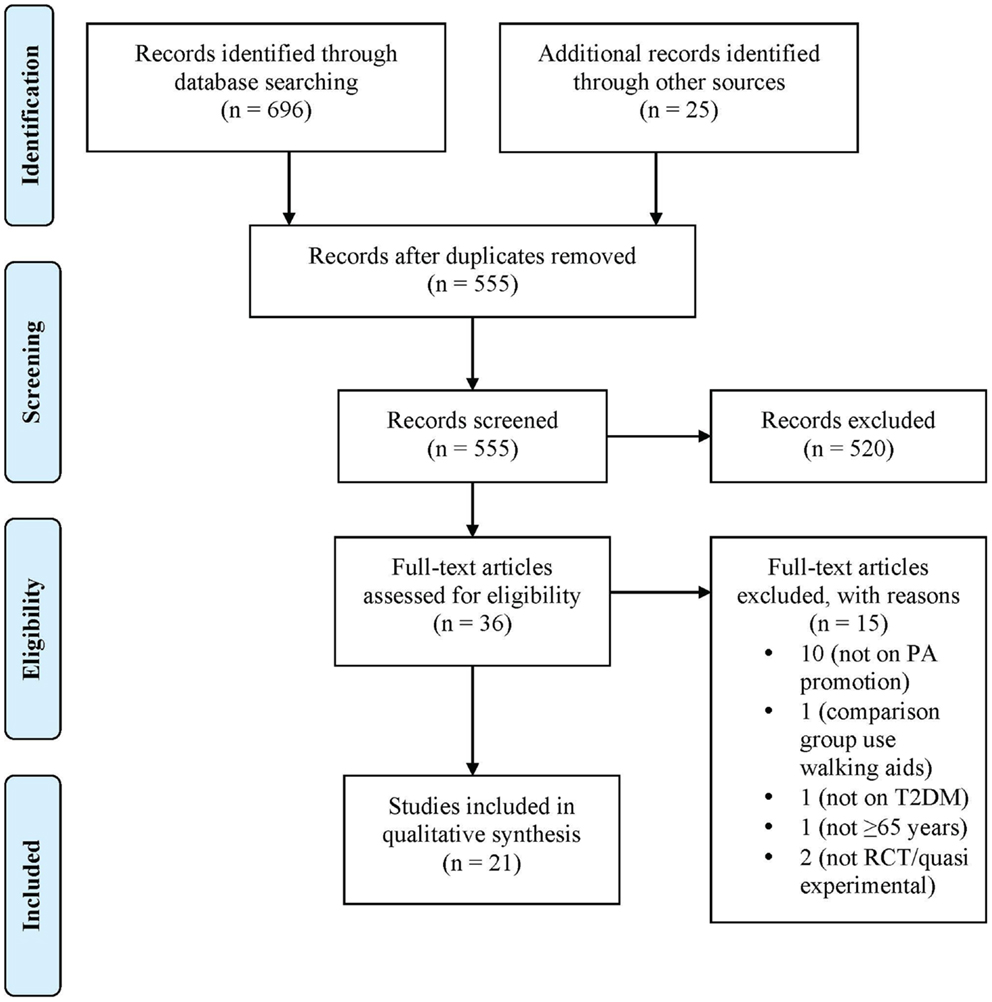

The initial search identified 696 potential articles from the database searches and another 26 were found through cross-referencing. A total of 520 studies were excluded because they did not examine physical activity, did not employ an RCT or quasi-experimental design, or did not examine T2DM or measure outcomes related to level of physical activity. A total of 36 full-text articles were selected and 21 were included in the final qualitative synthesis. Figure 1 describes the flow diagram for the study selection. We initially filtered for articles with persons aged 65 years and older, but the articles obtained from the database searches captured persons in younger age groups with some included persons aged 65 years and older. Hence, the selected studies in this review included studies that recruited both younger participants and participants aged 65 years and older.

Figure 1. Flow diagram for study selection according to PRISMA (19).

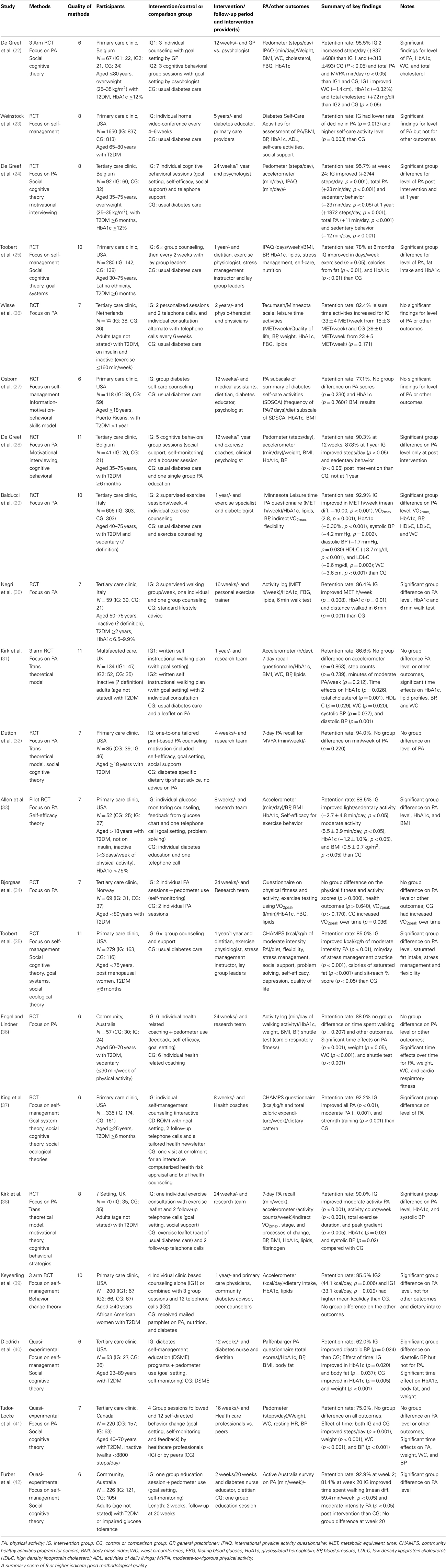

Table 3 describes the characteristics of included studies. Eighteen studies were RCTs (22–39) and three were quasi-experimental designs (40–42). Ten studies were conducted in North America (23, 25, 27, 32, 33, 35, 37, 39–41), nine studies conducted in Europe (22, 24, 26, 28–31, 34, 38), and two studies in Australia (36, 42). About half of the included studies’ interventions focused on physical activity (22, 24, 26, 28–34, 36, 38, 41) while others on self-management of T2DM. All studies included participants aged ≥65 years with T2DM and only one study specifically studied people aged 65–80 years (23).

The type of interventions used in each study varies markedly as shown in Table 3. Most interventions were delivered either as a group (22, 24, 25, 27, 28, 30, 35, 39, 41, 42) or using one-to-one counseling/advice (23, 24, 26, 29, 31–34, 36–38, 40). The majority of the studies’ interventions were delivered by one or more healthcare providers (22–30, 35, 37, 39–42) and some included peers as the interventionists (25, 35, 39, 41). In order to provide support and motivation, seven studies contacted the participants on ≥2 occasions in the first 4 weeks of the intervention (24–26, 29, 30, 35, 37).

Most studies incorporated one or a combination of health behavior theories in their interventions and social cognitive theory was the most commonly adopted theory (22, 24, 25, 32, 37, 40–42). Half of the included studies’ interventions were compared with control groups receiving usual diabetes care alone (22–27, 35). The outcome measures and results of interventions promoting physical activity are presented in Table 2. In most studies the primary outcome was either level of physical activity alone, or physical activity level in combination with other health outcomes. The level of physical activity were measured objectively using pedometer and/or accelerometer (22, 24, 28, 31, 33, 38, 39, 41) in combination with a questionnaire (22, 24, 31, 38). Eleven studies assessed level of physical activity subjectively using only a questionnaire (23, 25–27, 29, 32, 35–37, 40, 42), the content of which varied widely. The unit of measurement to represent the level of physical activity also varied.

Ten of the 12 studies which compared the physical activity intervention to a control group reported a significant increase in the level of physical activity in the intervention group (22–25, 28–30, 35, 37, 39). Some studies also reported improvements in HbA1c level (22, 25, 29, 30), other CVD risk factors (blood pressure, waist circumference, and lipid profiles) (22, 29) and in cardiorespiratory fitness (30). Nine studies which did not differ in number of contacts, but only on treatment procedure between the intervention and comparison groups, showed no difference between groups on physical activity level and CVD risk factors (31, 32, 34, 36, 41). Six of the 21 studies fulfilled nine or more criteria of methodological quality implying good quality studies (see Table 3) (25, 28, 29, 31, 35, 39). Only three studies applied intention-to-treat analysis principles (25, 30, 31). Studies with lower scores demonstrated methodological weaknesses related to randomization processes, sample size estimation, and outcomes assessment processes.

Discussion

This review identified 21 studies (18 RCTs and 3 quasi-experimental designs) that promoted physical activity in persons with T2DM, which involved older people. These studies were conducted in eight countries with none from the Asian region. The majority of the studies had participants in the middle age groups and only one study specifically recruited participants aged ≥65 years. Half of the studies focused on physical activity, while others focused on the self-management of diabetes. From this review, it is evident that significant heterogeneity in the interventions existed making comparisons difficult and any general conclusions must be made with caution.

The levels of physical activity of the participants often differed at randomization; hence, it was difficult to make valid conclusions about the effectiveness of these interventions. From this review, only three studies controlled for baseline physical activity. Other studies either controlled for variables that differed at baseline or there was no difference between groups at baseline and therefore the authors did not report controlling for baseline physical activity (27, 29, 32). Only a third of the studies targeted sedentary or inactive participants at recruitment, but the definition of sedentary or inactivity varied greatly (26, 29–31, 33, 36, 41). In some studies, the participants were asked to build on their present physical activity; hence, these participants may be physically active at recruitment. Participants who are already physically active are more likely to comply with physical activity interventions and maintain a healthy lifestyle than those who are sedentary or inactive (43).

Both one-to-one and group sessions improved the level of physical activity. However, most of these studies incorporated multiple constructs from health behavior theories including strategies such as goal setting, problem solving, self-monitoring, and social support in their interventions. It is assumed that these approaches incorporate multiple constructs and strategies to facilitate behavior change and maintenance (44). The constructs of social cognitive theory such as self-efficacy and social support were the most frequently used, with positive results in changing physical activity level (22, 24, 25, 33, 35, 37, 42) and improving glycemic control (22, 25, 33). However, this review is not able to provide the evidence to recommend the most suitable health behavior theories for future interventions. Some studies incorporated more than one health behavior theory in their interventions making comparison between studies difficult.

Interventions promoting physical activity with follow-up contacts during the study period did increase the level of physical activity and improved control of glycemia and other CVD risk factors. Five studies had a long period of intervention of at least 1-year duration (23, 25, 29, 35, 39) with reported long-term effects of the interventions for the level of physical activity. The effects of follow-up contacts with the intervention provider and long intervention duration could influence the observed positive outcomes in these studies.

The majority of the studies measured the level of physical activity as the primary outcome and most studies used a single physical activity outcome measure, predominantly validated self-reported scales or an activity log (23, 25–27, 29, 30, 32, 35, 36, 40, 42). Most of these studies did not use objective measures to assess the change in the level of physical activity but use self-report measures to obtain energy expenditure, total scale scores, oxygen uptake or the relative change in duration, frequency, and/or intensity of physical activity. Some studies did use objective measures such as motion sensor devices (accelerometer and/or pedometer) (22, 24, 28, 31, 33, 38, 41). However, self-reported physical activity scales do lack validity in measuring physical activity and were found to be inferior to the motion sensor devices (45, 46). This would lead to less precise measurement and misclassification of the level of physical activity. Hence, an objective measure of physical activity is necessary to establish the effect of intervention in a trial, as it allows a uniform measurement of the physical activity level.

In this current review, healthcare providers delivered the majority of the studies’ interventions and they may be more motivated to deliver the interventions than they might in a non-trial setting. In addition, the participants in most of these studies had to undergo extensive screening prior to randomization, and hence, participants who finally participated in these studies were more likely to be highly motivated (16). The evidence of effectiveness is also limited by the control or comparison groups, which varied widely. In some studies participants in the control group received only usual diabetes care or more general information about lifestyle changes while others received additional counseling about physical activity and some had multiple counseling sessions on diabetes self-care management. A number of studies included feedback from pedometer use, goal setting, and social support in the control/comparison groups as received by the intervention group as these studies were assessing a specific component of their intervention such as who delivers the interventions.

The methodological quality of the included studies in this review varies. Only six studies (all RCTs) were rated as good quality. The quality of the included studies in this review was limited by a lack of intention-to-treat analysis as only three studies perform such analysis. The studies with low scores have weaknesses in terms of inadequate description of the randomization methods; no information on random assignment performed by an independent person, insufficient description of sample size estimation and lack of information on whether an independent assessor assesses the main outcome measures. Inadequate methodological approaches in trials are associated with bias (47).

This review included multiple major databases with vigorous and systematic search strategy. However, there are limitations from this review. Only peer-reviewed papers published in recent years (i.e., from year 2000) and published in English are included in the data extraction, hence a possibility of selection bias exists. In addition, even though the searches are done thoroughly through multiple major databases with cross-referencing; there is a possibility that some papers are not included due to the inclusion criteria used for this current review. In this review, only one reviewer assessed the studies for eligibility, which could contribute to an increased risk of evaluation bias.

Conclusion

The number of well-designed trials on interventions promoting physical activity in older people with T2DM is limited as evident in this present review. The methodological quality, type of interventions promoting physical activity and outcome measure for level of physical activity in the included studies included in this review differed widely. Studies with interventions promoting physical activity that compared with usual diabetes care do have significant findings in changing the level of physical activity in persons with T2DM. Moreover, on-going follow-up support seems to contribute in increasing level of physical activity. However, these studies are restricted to middle-aged persons with T2DM in western countries. In addition, very few studies had follow-up assessment post intervention to allow evaluation on sustainability of interventions promoting physical activity. Peer support for adults with T2DM may have potential in promoting physical activity but the evidence is scarce. Furthermore, standardization on the measure for physical activity with the use of objective tool such as the pedometer or the accelerometer is needed to allow a uniform classification of level of physical activity. Therefore, further exploration in these areas is warranted when developing interventions to promote physical activity in older people with T2DM.

Authors Contribution

Colette Browning conceived the primary research question for the study. Shariff-Ghazali Sazlina, Colette Browning, and Shajahan Yasin were involved in the study conception and design. Shariff-Ghazali Sazlina was responsible for data extraction and Shajahan Yasin assessed any doubtful papers. Shariff-Ghazali Sazlina interpreted the results and drafted the initial manuscript. Colette Browning and Shajahan Yasin provided input on interpretation of results and provided critical revision to the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. International Diabetes Federation. Diabetes Atlas. 4th ed. Brussels: International Diabetes Federation (2010).

2. Shaw JE, Sicree RA, Zimmet PZ. Global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2010 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract (2010) 87(1):4–14. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.10.007

3. Zhang P, Zhang X, Brown J, Vistisen D, Sicree R, Shaw J, et al. Global healthcare expenditure on diabetes for 2010 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract (2010) 87(3):293–301. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2010.01.026

4. Sigal RJ, Kenny GP, Boulé NG, Wells GA, Prud’Homme D, Fortier M, et al. Effects of aerobic training, resistance training, or both on glycemic control in type 2 diabetes. Ann Intern Med (2007) 147(6):357–369. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-147-6-200709180-00005

5. Church TS, LaMonte MJ, Barlow CE, Blair SN. Cardiorespiratory fitness and body mass index as predictors of cardiovascular disease mortality among men with diabetes. Arch Intern Med (2005) 165(18):2114–20. doi:10.1001/archinte.165.18.2114

6. Chodzko-Zajko WJ, Proctor DN, Fiatarone Singh MA, Minson CT, Nigg CR, Salem GJ, et al. Exercise and physical activity for older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc (2009) 41(7):1510–30. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181a0c95c

7. Nelson ME, Rejeski WJ, Blair SN, Duncan PW, Judge JO, King AC, et al. Physical activity and public health in older adults. Recommendation from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Circulation (2007) 116(9):1094–105. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.185650

8. Thomas D, Elliott EJ, Naughton GA. Exercise for type 2 diabetes mellitus. The Cochrane Collaboration. In: Thomas D, editor. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews [Internet]. (2006). Available from: http://www2.cochrane.org/reviews/en/ab002968.html

9. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Prevalence and Trends Data from Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System – Physical Activity, 2009 [Internet]. (2009). Available from: http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/BRFSS/display.asp?cat=PA&yr=2009&qkey=4418&state=UB

10. Australian Bureau of Statistics. National Health Survey: Summary of results [Internet]. (2006). Available from: www.ausstats.abs.gov.au

11. Ng N, Hakimi M, Hoang VM, Juvekar S, Razzaque A, Ashraf A, et al. Prevalence of physical inactivity in nine rural INDEPTH Health and Demographic Surveillance Systems in five Asian countries. Glob Health Action (2009) 2(Suppl 1):44–53. doi:10.3402/gha.v2i0.1985

12. Kruger J, Carlson SA, Buchner D. How active are older Americans? Prev Chronic Dis (2007) 4(3):A53–4.

13. Chua LAV. Personal Health Practices – Different Patterns in Males and Females. Statistics Singapore Newsletter. Singapore (2009). p. 12–6. Available from: http://www.singstat.gov.sg/publications/newsletter/archive/ssnmar2009.pdf

14. Kahn EB, Ramsey LT, Brownson RC, Heath GW, Howze EH, Powell KE, et al. The effectiveness of interventions to increase physical activity: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med (2002) 22(4, Suppl 1):73–107. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(02)00434-8

15. Ashworth NL, Chad KE, Harrison EL, Reeder BA, Marshall SC. Home versus center based physical activity programs in older adults. In: Ashworth NL, editor. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews [Internet]. (2005). Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com.ezproxy.lib.monash.edu.au/o/cochrane/clsysrev/articles/CD004017/abstract.html

16. van den Berg MH, Schoones JW, Vliet Vlieland TP. Internet-based physical activity interventions: a systematic review of the literature. J Med Internet Res (2007) 9(3):e26. doi:10.2196/jmir.9.3.e26

17. Greaves CJ, Sheppard KE, Abraham C, Hardeman W, Roden M, Evans PH, et al. Systematic review of reviews of intervention components associated with increased effectiveness in dietary and physical activity interventions. BMC Public Health (2011) 11(1):119. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-11-119

18. Foster C, Hillsdon M, Thorogood M. Interventions for promoting physical activity. The Cochrane Collaboration. In: Foster C, editor. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews [Internet]. (2005). Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com.ezproxy.lib.monash.edu.au/o/

cochrane/clsysrev/articles/CD003180/abstract.html

19. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med (2009) 6(7):e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

20. Estabrooks CA, Field PA, Morse JM. Aggregating qualitative findings: an approach to theory development. Qual Health Res (1994) 4(4):503–11. doi:10.1177/104973239400400410

21. Van Tulder M, Furlan A, Bombardier C, Bouter L. Updated method guidelines for systematic reviews in the Cochrane Collaboration Back Review Group. Spine (2003) 28(12):1290–9. doi:10.1097/00007632-200306150-00014

22. De Greef K, Deforche B, Tudor-Locke C, De Bourdeaudhuij I. Increasing physical activity in Belgian type 2 diabetes patients: a three-arm randomized controlled trial. J Behav Med (2011) 18(3):188–98. doi:10.1007/s12529-010-9124-7

23. Weinstock RS, Brooks G, Palmas W, Morin PC, Teresi JA, Eimicke JP, et al. Lessened decline in physical activity and impairment of older adults with diabetes with telemedicine and pedometer use: results from the IDEATel study. Age Ageing (2011) 40(1):98–105. doi:10.1093/ageing/afq147

24. De Greef K, Deforche B, Ruige J, Bouckaert J, Tudor-Locke C, Kaufman J, et al. The effects of a pedometer-based behavioral modification program with telephone support on physical activity and sedentary behavior in type 2 diabetes patients. Patient Educ Couns (2011) 84(2):275–9. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2010.07.010

25. Toobert DJ, Strycker LA, Barrera M Jr, Osuna D, King DK, Glasgow RE. Outcomes from a multiple risk factor diabetes self-management trial for Latinas: ¡Viva Bien! Ann Behav Med (2011) 41(3):310–23. doi:10.1007/s12160-010-9256-7

26. Wisse W, Rookhuizen MB, de Kruif MD, van Rossum J, Jordans I, ten Cate H, et al. Prescription of physical activity is not sufficient to change sedentary behavior and improve glycemic control in type 2 diabetes patients. Diabetes Res Clin Pract (2010) 88(2):e10–3. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2010.01.015

27. Osborn CY, Amico KR, Cruz N, O’Connell AA, Perez-Escamilla R, Kalichman SC, et al. A brief culturally tailored intervention for Puerto Ricans with type 2 diabetes. Health Educ Behav (2010) 37(6):849–62. doi:10.1177/1090198110366004

28. De Greef K, Deforche B, Tudor-Locke C, De Bourdeaudhuij I. A cognitive-behavioural pedometer-based group intervention on physical activity and sedentary behaviour in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Health Educ Res (2010) 25(5):724–36. doi:10.1093/her/cyq017

29. Balducci S, Zanuso S, Nicolucci A, De Feo P, Cavallo S, Cardelli P, et al. Effect of an intensive exercise intervention strategy on modifiable cardiovascular risk factors in subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial: the Italian Diabetes and Exercise Study (IDES). Arch Intern Med (2010) 170(20):1794–803. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2010.380

30. Negri C, Bacchi E, Morgante S, Soave D, Marques A, Menghini E, et al. Supervised walking groups to increase physical activity in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care (2010) 33(11):2333–5. doi:10.2337/dc10-0877

31. Kirk A, Barnett J, Leese G, Mutrie N. A randomized trial investigating the 12-month changes in physical activity and health outcomes following a physical activity consultation delivered by a person or in written form in Type 2 diabetes: Time2Act. Diabet Med (2009) 26(3):293–301. doi:10.1111/j.1464-5491.2009.02675.x

32. Dutton GR, Provost BC, Tan F, Smith D. A tailored print-based physical activity intervention for patients with type 2 diabetes. Prev Med (2008) 47(4):409–11. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.06.016

33. Allen NA, Fain JA, Braun B, Chipkin SR. Continuous glucose monitoring counseling improves physical activity behaviors of individuals with type 2 diabetes: a randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Res Clin Pract (2008) 80(3):371–9. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2008.01.006

34. Bjørgaas MR, Vik JT, Stølen T, Lydersen S, Grill V. Regular use of pedometer does not enhance beneficial outcomes in a physical activity intervention study in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Metabolism (2008) 57(5):605–11. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2007.12.002

35. Toobert DJ, Glasgow RE, Strycker LA, Barrera M Jr, Ritzwoller DP, Weidner G. Long-term effects of the Mediterranean lifestyle program: a randomized clinical trial for postmenopausal women with type 2 diabetes. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act (2007) 4(1). doi:10.1186/1479-5868-4-1

36. Engel L, Lindner H. Impact of using a pedometer on time spent walking in older adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ (2006) 32(1):98–107. doi:10.1177/0145721705284373

37. King DK, Estabrooks PA, Strycker LA, Toobert DJ, Bull SS, Glasgow RE. Outcomes of a multifaceted physical activity regimen as part of a diabetes self-management intervention. Ann Behav Med (2006) 31(2):128–37. doi:10.1207/s15324796abm3102_4

38. Kirk A, Mutrie N, MacIntyre P, Fisher M. Increasing physical activity in people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care (2003) 26(4):1186–92. doi:10.2337/diacare.26.4.1186

39. Keyserling TC, Samuel-Hodge CD, Ammerman AS, Ainsworth BE, Henríquez-Roldán CF, Elasy TA, et al. A randomized trial of an intervention to improve self-care behaviors of African-American women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care (2002) 25(9):1576–1583. doi:10.2337/diacare.25.9.1576

40. Diedrich A, Munroe DJ, Romano M. Promoting physical activity for persons with diabetes. Diabetes Educ (2010) 36(1):132–40. doi:10.1177/0145721709352382

41. Tudor-Locke C, Lauzon N, Myers AM, Bell RC, Chan CB, McCargar L, et al. Effectiveness of the First Step Program delivered by professionals versus peers. J Phys Act Health (2009) 6(4):456–62.

42. Furber S, Monger C, Franco L, Mayne D, Jones LA, Laws R, et al. The effectiveness of a brief intervention using a pedometer and step-recording diary in promoting physical activity in people diagnosed with type 2 diabetes or impaired glucose tolerance. Health Promot J Austr (2008) 19(3):189–95.

43. Bock BC, Marcus BH, Pinto BM, Forsyth LH. Maintenance of physical activity following an individualized motivationally tailored intervention. Ann Behav Med (2001) 23(2):79–87. doi:10.1207/S15324796ABM2302_2

44. Nigg CR, Allegrante JP, Ory M. Theory-comparison and multiple-behavior research: common themes advancing health behavior research. Health Educ Res (2002) 17(5):670–9. doi:10.1093/her/17.5.670

45. Harris T, Owen CG, Victor CR, Adams R, Ekelund U, Cook DG. A comparison of questionnaire, accelerometer, and pedometer: measures in older people. Med Sci Sports Exerc (2009) 41(7):1392–402. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e31819b3533

46. Ewald B, McEvoy M, Attia J. Pedometer counts superior to physical activity scale for identifying health markers in older adults. Br J Sports Med (2010) 44(10):756–61. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2008.048827

Keywords: physical activity, older people, type 2 diabetes mellitus, geriatric medicine, health promotion

Citation: Sazlina S-G, Browning C and Yasin S (2013) Interventions to promote physical activity in older people with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Front. Public Health 1:71. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2013.00071

Received: 19 August 2013; Paper pending published: 29 October 2013;

Accepted: 04 December 2013; Published online: 23 December 2013.

Edited by:

Sue Ellen Levkoff, University of South Carolina, USAReviewed by:

Y. Tony Yang, George Mason University, USASue Ellen Levkoff, University of South Carolina, USA

Copyright: © 2013 Sazlina, Browning and Yasin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Colette Browning, School of Primary Health Care, Monash University, Building 1, 270 Ferntree Gully Road, Notting Hill, VIC 3168, Australia e-mail: colette.browning@monash.edu

Shariff-Ghazali Sazlina

Shariff-Ghazali Sazlina Colette Browning

Colette Browning Shajahan Yasin2

Shajahan Yasin2