The in Vitro Antigenicity of Plasmodium vivax Rhoptry Neck Protein 2 (PvRON2) B- and T-Epitopes Selected by HLA-DRB1 Binding Profile

- 1Molecular Biology and Immunology Department, Fundación Instituto de Inmunología de Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia

- 2PhD Program in Biomedical and Biological Sciences, Universidad del Rosario, Bogotá, Colombia

- 3MSc Program in Microbiology, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia

- 4Faculty of Agricultural Sciences, Universidad de Ciencias Aplicadas y Ambientales, Bogotá, Colombia

- 5School of Medicine, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia

- 6Basic Sciences Department, School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universidad del Rosario, Bogotá, Colombia

Malaria caused by Plasmodium vivax is a neglected disease which is responsible for the highest morbidity in both Americas and Asia. Despite continuous public health efforts to prevent malarial infection, an effective antimalarial vaccine is still urgently needed. P. vivax vaccine development involves analyzing naturally-infected patients' immune response to the specific proteins involved in red blood cell invasion. The P. vivax rhoptry neck protein 2 (PvRON2) is a highly conserved protein which is expressed in late schizont rhoptries; it interacts directly with AMA-1 and might be involved in moving-junction formation. Bioinformatics approaches were used here to select B- and T-cell epitopes. Eleven high-affinity binding peptides were selected using the NetMHCIIpan-3.0 in silico prediction tool; their in vitro binding to HLA-DRB1*0401, HLA-DRB1*0701, HLA-DRB1*1101 or HLA-DRB1*1302 was experimentally assessed. Four peptides (39152 (HLA-DRB1*04 and 11), 39047 (HLA-DRB1*07), 39154 (HLADRB1*13) and universal peptide 39153) evoked a naturally-acquired T-cell immune response in P. vivax-exposed individuals from two endemic areas in Colombia. All four peptides had an SI greater than 2 in proliferation assays; however, only peptides 39154 and 39153 had significant differences compared to the control group. Peptide 39047 was able to significantly stimulate TNF and IL-10 production while 39154 stimulated TNF production. Allele-specific peptides (but not the universal one) were able to stimulate IL-6 production; however, none induced IFN-γ production. The Bepipred 1.0 tool was used for selecting four B-cell epitopes in silico regarding humoral response. Peptide 39041 was the only one recognized by P. vivax-exposed individuals' sera and had significant differences concerning IgG subclasses; an IgG2 > IgG4 profile was observed for this peptide, agreeing with a protection-inducing role against P. falciparum and P. vivax as previously described for antigens such as RESA and MSP2. The bioinformatics results and in vitro evaluation reported here highlighted two T-cell epitopes (39047 and 39154) being recognized by memory cells and a B-cell epitope (39041) identified by P. vivax-exposed individuals' sera which could be used as potential candidates when designing a subunit-based vaccine.

Background

Malaria is one of the most important public health problems in tropical and subtropical regions worldwide. Nearly 3.3 billion people globally are at risk of contracting the disease; 214 million new cases appeared and 438,000 deaths occurred in 2015. Malaria is caused by parasites from the phylum Apicomplexa, genus Plasmodium. Plasmodium vivax is the second most prevalent known species and has the greatest geographical distribution as it can develop in its vector at lower temperatures and survive at higher altitudes. It also has a latent form known as hypnozoite; this remains in the hepatocytes, enabling parasite survival in a host for a long time (Mueller et al., 2009; Guerra et al., 2010; WHO, 2016).

Although malarial cases in Latin America decreased during the last decade, a rise in cases reported from Venezuela and Colombia has been reported in 2015 and 2016 (PAHO/WHO, 2017), Colombia being listed as the fourth regarding incidence during 2015 (i.e., 10% of malarial events) (WHO, 2016). A passive surveillance study of malarial transmission in Colombia between 2011 and 2013 showed that 50.7% of cases were caused by P. vivax, 48.9% by P. falciparum and 0.4% mixed infection (Arévalo-Herrera et al., 2015). A severe malaria study on Colombia's Pacific coast showed that P. vivax induced acute anemia in children and P. falciparum patients had high renal and hepatic damage rates (Arévalo-Herrera et al., 2017).

Since P. vivax has wide-scale global distribution, some strategies used to combat malaria involve using insecticide-impregnated mosquito nets and drugs such as sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine, artemisinin, and chloroquine (WHO, 2016); despite such efforts, vector insecticide resistance and parasite resistance to anti-malarial drug has increased during recent years (Rieckmann et al., 1989; Fairhurst and Dondorp, 2016). Administering anti-malarial drugs, together with developing an effective antimalarial vaccine, is considered a relevant control strategy for preventing and eradicating malaria (WHO, 2016).

More than 50 proteins have been described to date as being involved in malarial parasite's red blood cell (RBC) invasion; most have been identified at molecular level and characterized immunologically in P. falciparum (Bozdech et al., 2003; Cowman and Crabb, 2006). Conversely, studying P. vivax proteins involved in host invasion has been difficult, mainly due to technical restrictions such as the lack of a continuous in vitro parasite culture, leading to inadequate study of parasite biology (Udomsangpetch et al., 2008; Mueller et al., 2009).

Parasites from the phylum Apicomplexa have specialized organelles such as rhoptries which contain a large amount of proteins involved in host cell invasion (Counihan et al., 2013). Six P. vivax rhoptry neck proteins have been identified to date: Pv34, PvRON1, PvRON2, PvRON4, PvRALP and PvRON5 (Mongui et al., 2009; Arévalo-Pinzón et al., 2011, 2013, 2015; Moreno-Perez et al., 2011; Cheng et al., 2015). They have been described as possible targets for blocking P. vivax invasion of RBC (Mongui et al., 2009).

P. vivax rhoptry neck protein 2 (PvRON2) is 2,204 amino acids (aa) long and is expressed in late schizont rhoptries (Arévalo-Pinzón et al., 2011). It is a highly conserved protein which is secreted by specialized organelles and forms part of the complex of proteins called RONs. This protein, like its orthologs in T. gondii (TgRON2) and P. falciparum (Pf RON2) interacts directly with the AMA-1 protein. The RON complex is involved in forming the moving junction (MJ) (electro dense ring-shaped structure) which allows parasite entry to a host cell (Aikawa et al., 1978; Lamarque et al., 2011). RON2's crucial role during merozoite (Mrz) invasion of erythrocytes, moving junction (MJ) formation and subsequent parasitophorous vacuole (PV) formation (Cao et al., 2009; Collins et al., 2009; Srinivasan et al., 2011) makes it a good vaccine candidate. Moreover, Srinivasan et al. have shown that vaccination with the Pf AMA1-RON2L complex induce protection in Aotus monkeys, mediated by high neutralizing antibody titers that prevent the invasion of RBC (Srinivasan et al., 2017).

The development of bioinformatics tools during the last few decades has enabled predicting vaccine candidates based on peptide binding affinity for major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I or class II (Sturniolo et al., 1999; Nielsen and Lund, 2009; Wang et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2012; Andreatta et al., 2015). The immune system's function is to recognize and differentiate between self and non-self-antigens so as to trigger cellular and/or humoral immune responses. MHC class II proteins (HLA-II in humans) are expressed on antigen presenting cells' (APC) surface (i.e., macrophages, dendritic cells and B-lymphocytes). These recognize extracellular antigens and can bind 13- to 18-aa-long peptides. One of the main difficulties in designing a vaccine is the high HLA polymorphism, especially from HLA-DRB1, this being the most polymorphic locus. Antigen binding capability varies from one allele to another, increasing or reducing affinity and driving immune responses. Selecting peptides as good vaccine candidates relies on their ability to be recognized by HLA-DRB1 alleles to ensure a protection-inducing immune response (Stern and Calvo-Calle, 2009). T-cells can trigger stronger immune responses after their APC recognition, depending on the peptides bound to MHC receptors (Blum et al., 2013).

Antigen-antibody interaction plays an essential role in humoral immune responses against pathogens. Bioinformatics tools are extremely useful for identifying antigenic determinants or B-cell epitopes when designing vaccines (Bergmann-Leitner et al., 2013; Panda and Mahapatra, 2017). Predicting linear B-cell epitopes (contiguous aa in a protein sequence) is based on several methods for determining aa physicochemical properties, such as solvent accessibility, hydrophilicity and flexibility (El-Manzalawy et al., 2017; Solihah et al., 2017).

This paper describes naturally-acquired T-cell and antibody immune responses to PvRON2 in P. vivax-exposed individuals from two of Colombia's endemic areas (Córdoba and Chocó), in the search for vaccine candidates. Eleven high-affinity epitopes were selected by NetMHCIIpan-3.0 (Andreatta et al., 2015) in silico prediction and their in vitro binding to at least one of HLA-DRB1*0401, HLA-DRB1*0701, HLA-DRB1*1101 and HLA-DRB1*1302 was assessed by competition assays. The Bepripred 1.0 tool was used for selecting four B-cell epitopes in silico. A good immune response was observed against two T-cell and one B-cell epitopes; further studies aimed at testing these peptides as components of a subunit vaccine against P. vivax are thus recommended.

Materials and Methods

In Silico B-Cell and T-Cell Epitope High Binding Prediction

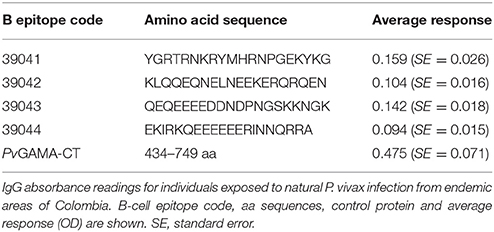

The PvRON2 aa sequence (PlasmoDB database code: PVX_117880) was used for predicting T-cell epitopes having high binding affinity for the HLA-DRB1 alleles most frequently occurring in endemic areas worldwide (HLA-DRB1*0401, HLA-DRB1*0701, HLA-DRB1*1101, and HLA-DRB1*1302) (Marsh et al., 1999). NetMHCIIpan-3.0 (Andreatta et al., 2015) was used for predicting these epitopes and confirmed by IEDB (Sturniolo et al., 1999; Nielsen and Lund, 2009; Wang et al., 2010) and TEPITOPE software (Zhang et al., 2012). Three epitopes per HLA-DRB1 were selected for in vitro analysis according to highest predicted binding values (Table 1).

Bepipred 1.0 (Larsen et al., 2006) and Antheprot 2000 V6.0 (Deléage et al., 2001) were used for predicting B-cell epitopes. Four epitopes were chosen as they agreed with average high Parker antigenicity, hydrophilicity and solvent accessibility values obtained with Antheprot software, and the high values obtained with the Bepipred tool (0.35 default threshold and 75% specificity); such peptides were further used for analyzing humoral responses in vitro (Table 2).

Synthetic Peptides

Peptides selected in silico were purchased from Twenty First Century Biochemicals Inc. (260 Cedar Hill Street Marlboro, MA 01752 USA) and characterized by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS). The biotinylated peptides used as control for HLA peptide binding in competition assays were synthesized using sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin (Pierce Chemical, Rockford).

HLA-DR Molecules Purification

HLA-DRB1* molecules were purified from human HLA-DRB1*0401 (IHW09025), HLA-DRB1*0701 (IHW09051), HLA-DRB1*1101 (IHW09043) and HLA-DRB1*1302 (IHW09055) homozygous lymphoblastoid B-cell lines (International Histocompatibility Working Group) and cultured in RPMI-1640 (Gibco) with 10% FBS (Gibco), at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. The purification was carried out as previously described by Vargas et al. (2003), briefly 5 × 109 cells were lysed at 1 × 108 cell/mL final density in lysis buffer with 10 μg/mL protease inhibitors [antipain, pepstatin A, soybean trypsin, leupeptin, and chymostatin (SIGMA-ALDRICH)]. The lysate was mixed with Protein A-Sepharose CL-4B beads (GE Healthcare) linked to mAb L243 (ATCC HB-55; anti-DR was purified by affinity chromatography using Protein A-Sepharose CL-4B beads) overnight, HLA-DRB1* molecules were obtained by affinity chromatography. HLA-DRB1 protein purity was confirmed by native SDS-PAGE (12%) and Western-blot; positive aliquots' concentration was determined by the Micro BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific); HLA-DRB1 proteins were stored at −80°C until use.

In Vitro Peptide-Binding Assays and IC50 Values

Peptide binding competition assays were performed to test PvRON2 high-affinity binding peptides selected by in silico analysis using NetMHCIIpan 3.0 software. Selected unlabeled peptides competed with biotinylated control peptide in binding to HLA-DRB1*. The biotinylated peptides used were haemagglutinin antigen HA306−318 (PKYVKQNTLKLAT) for HLA-DRB1*04 and HLA-DRB1*11 (Hammer et al., 1994; Saravia et al., 2008) and tetanus toxoid (TT) (QYIKANSKFIGITE) for HLA-DRB1*07 and HLA-DRB1*13 (Doolan et al., 2000).

HLA-DR molecules (0.1 μM) were incubated for 24 h with 5 μM biotinylated HA or TT peptides and a 50-fold excess of unlabeled peptide (250 μM). The mix was incubated for 2 h in Maxisorb NUNC-immune modules (Thermo Scientific) covered with anti-DR. The complex was incubated with alkaline phosphatase streptavidin (Vector Labs) and as substrate alkaline phosphatase yellow (pNPP) liquid substrate (Sigma-Aldrich). Optical density (OD) was determined at 405 nm using a Multiskan GO (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) ELISA reader. Inhibition was calculated as a percentage, by using the following formula:

IC50 values (50% concentration inhibition) were determined for peptides able to inhibit high-affinity control peptide binding to a particular HLA-DR by more than 50% (Saravia et al., 2008). The peptides and control peptides were tested in 5–250 μM serial dilutions for the competition assays; Mathematica (version 10.1) software (Wolfram Research, Inc., Mathematica, Champaign, IL 2015) was used for calculating IC50 values, using two-phase exponential decay. IC50 values were calculated as a relative value using the following formula:

Study Population

Peripheral blood was obtained from 79 people living in the Colombian departments of Chocó and Córdoba (known P. vivax malaria endemic areas, having the highest case incidence) who had suffered previous episodes of malaria. Inclusion criteria consisted of being over 18 years-old, residing in a P. vivax-endemic area, having had 1 or more episodes of P. vivax malaria (the last one 6 months beforehand) and having received suitable treatment for the disease. Although a stronger immune response would have been expected in acutely-infected P. vivax individuals, the construction of study groups required a prior HLA typing and thus, a second sample had to be taken from individuals matching the alleles of interest to assess antigenicity. Taking this into account, the antigenicity sample was taken from people that had suffered P. vivax malaria at least 6 months earlier. A control group of 50 individuals was selected; this consisted of healthy adults residing in Bogotá, Colombia, who had never lived in malaria-endemic areas and who had never experienced malarial infection. This study was performed according to the legal framework for research in Colombia and Ministry of Health's Resolution 8430 of 1993. The patients had the least risk, all data were kept confidential and were rigorously protected. The samples were collected after all individuals signed an informed consent form; all procedures were evaluated and approved by FIDIC's ethics committee.

HLA-DRB1 Typing

Genomic DNA (gDNA) from 300 μL peripheral blood samples was extracted using a Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega Corporation, Madison, USA), following the manufacturer's instructions. gDNA was used for high resolution HLA-DRB1 typing by Histogenetics (Ossining, NY, USA) through Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) technology using Illumina MiSeq.

PBMC Isolation

Twenty-nine people carrying HLA-DRB1 typing for HLA-DRB1*04, HLA-DRB1*07, HLA-DRB1*11 and HLA-DRB1*13 alleles were selected from P. vivax endemic areas of Colombia's Córdoba and Chocó departments. Eight people carrying the same HLA-DRB1* alleles from a non-endemic area formed the control group. About 40 mL peripheral blood was collected in citrate phosphate dextrose (CPD) tubes and 6 mL peripheral blood in BD vacutainer serum collection tubes (BD Vacutainer Oakville, ON). Thick blood smears were used for confirming samples negative for malaria. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated by Ficoll-Paque PLUS (GE Healthcare) gradient centrifugation. Briefly, the buffy coat was resuspended in RPMI 1640 (Gibco) and separated by Ficoll, spinning at 1,000 g for 30 min at room temperature (RT). Mononuclear cells were collected, washed and spun at 800 g for 10 min, twice. Cell viability was evaluated by trypan blue exclusion test and cells were counted in a Neubauer chamber.

T-Cell Proliferation

Briefly, 2 × 105 PBMC were cultured in 200 μL RPMI-1640 (Gibco), 2 mM glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 2 g/L sodium bicarbonate, 100 μg/mL streptomycin and 100 U/mL penicillin (all Gibco) and 10% heat-inactivated autologous plasma in 96-well round-bottomed plates (Costar, Corning Incorporated). Proliferation activity was evaluated by flow cytometry using carboxyfluorescein diacetate N-succinimidyl ester (CFSE, 5μM) (CellTrace CFSE cell proliferation kit, Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oregon, USA) reduction in replicating cells.

The cells were left without stimulation (unstimulated control) or were stimulated by co-culture with synthetic peptides (10 μg/mL) or 2% mitogen phytohemagglutinin (PHA) (Sigma) or 5 μg/mL P. vivax lysate as positive controls. Pv12 low binding peptide was selected (39115) by binding assay and used as negative control (manuscript in preparation). The 96-well plates were incubated in 5% CO2 at 37°C for 5 days; 100 μL culture supernatant was then collected per well and stored at −80°C until analysis for cytokine production. Duplicate assays were carried out.

The CD4-Pacific Blue-stained cell stimulation index was calculated by proliferative cells' relative percentage loss of carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) in the presence of antigen, divided by percentage relative CFSE loss for proliferative cells without antigen (Racanelli et al., 2011). Data was averaged for each antigen and for both exposed individuals and control groups. SI ≥ 2 was taken as antigen-specific positive proliferation. A Pacific Blue-labeled mouse anti-human CD4 (RPA-T4 clone) antibody (BD Biosciences), was used for CFSE-cell cluster measure. The samples were then read on a FACS Canto II flow cytometer; FlowJo software (v7.6.5, Ashland, Oregon, USA) was used for analyzing the results.

Cytokine Secretion

IFN-γ, TNF, IL-10, and IL-6 levels in lymphocyte culture supernatant were determined with a BD CBA Human Th1/Th2 Cytokine Kit II (San Jose, CA, USA), following the manufacturer's instructions. Supernatants were read on a FACS Canto II flow cytometer; FCAP Array software (v3.0.1) was used for analyzing the results. Results were expressed in pg/mL for each cytokine; data were compared between unstimulated and stimulated PBMC supernatant culture. Two standard deviations higher than that for control group were taken as positive antigen-specific production.

Indirect Immunofluorescence Assays (IFA)

IFA followed that previously described by Moreno-Pérez et al. (2013) with some modifications. Briefly, blood samples from individuals having active P. vivax infection were spun at 1,750 g for 12 min at RT. Both plasma and buffy coat were recovered and parasite red blood cells (pRBC) were washed with saline solution. pRBC were passed through a 60% Percoll gradient and spun at 1,750 g for 20 min. P. vivax-pRBC were diluted until 5–7 schizonts per field and confirmed by acridine orange. Twenty μL of diluted pRBC were placed into multitest microscope slide wells (Tekdon Incorporated) and incubated for 30 min. The supernatant was then removed, and microscopic slides left overnight (ON) at room temperature (RT) to air dry. The slides were then blocked for 30 min at RT with tris-buffered saline (TBS) 1% bovine serum albumin (TBSA) solution and washed three times. The serum samples from 30 exposed individuals and 8 sera from the control group were diluted in TBSA at 1:50 dilution and incubated for 1 h in a humid chamber. Reactivity was observed by fluorescence microscopy using anti-human IgG-FITC antibody (Sigma-Aldrich) diluted 1:50 in TBSA for 45 min in a humid chamber. The parasite nuclei were stained with 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylinodole dihydrochloride (DAPI) (0.25 μg/mL) for 5 min at RT and washed twice with 0.05% TBS-Tween 20 and three washes with TBS to remove excess reagent. The slides were visualized on an Olympus BX51 fluorescence microscope, using 100X oil immersion objective; DP2-BSW software (v2.2 Olympus Corporation) was then used to take images and ImageJ 1.51n software (National Institutes of Health, USA) for merging images.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent (ELISA) and Subclass IgG Assays

Total IgG antibodies were measured in serum from exposed individuals and control group. Maxisorb NUNC-immune modules (Thermo Scientific) were coated with 1 μg of each epitope and of rPvGAMA (10 μg/mL) (Baquero et al., 2017) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.2, and incubated ON at 4°C. The immune modules were washed three times with PBS-0.05% Tween 20 solution (PBST) the next day and then blocked with 2.5% (wt/vol) non-fat powdered milk in PBST solution for 1 h at RT. Serum at 1:100 dilution was incubated for 2 h (100 μL per well) in duplicate. Secondary antibody horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-human IgG (Vector labs) was added at 1:10,000 dilution in blocked solution and incubated for 1 h at RT. TMB 2-Component Microwell Peroxidase Substrate (Sera-Care) was added at 100 μL/well to detect monoclonal antibody binding. The reaction was stopped by adding an equal volume of 1M phosphoric acid (H3PO4); OD was measured at 450 nm using a Multiskan GO (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) ELISA reader. Cut-off value was determined as negative control serum samples' mean plus two standard deviations; IgG subclasses were determined for positive total IgG serum.

The ELISA protocol described above was followed to evaluate IgG subclasses with minor modifications, as follows: 3% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin (BSA, Sigma) in PBST was used as blocking agent/solution and serum at 1:100 dilution was incubated for 2 h in duplicate. A 1:1,000 dilution of monoclonal anti-human IgG1–biotin antibody produced in mouse (clone 8c/6-39), 1:15,000 monoclonal anti-human IgG2–biotin antibody produced in mouse (clone HP-6014), 1:40,000 monoclonal anti-human IgG3–biotin antibody produced in mouse (clone HP-6050) and 1:60,000 anti-human IgG4–biotin antibody, mouse monoclonal (clone HP-6025) (Sigma Aldrich) were used. ImmunoPure streptavidin, horseradish peroxidase conjugate (Thermo Scientific), at 1:5,000, dilution, was used as secondary antibody and TMB 2-Component Microwell peroxidase as substrate. The reaction was stopped by adding an equal volume of 1M phosphoric acid (H3PO4). OD was measured at 450 nm, using a Multiskan GO ELISA reader (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA).

Statistical Analysis

GraphPad Prism software (version 5.0, San Diego, CA, USA) was used for analysis and constructing graphs. A Mann-Whitney test was used for comparing two groups regarding non-parametric data and Kruskal-Wallis test (with Dunn's multiple comparison post-test) for comparing more than two groups. Student's t-test was used for comparing two groups of data having a normal distribution. A 95% confidence interval was used. p ≤ 0.05 was considered significant. Significance level has been highlighted on all graphs by asterisks, as follows: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.005, and ***p < 0.0005.

Results

T-Epitope Selection According in Vitro Binding Profile

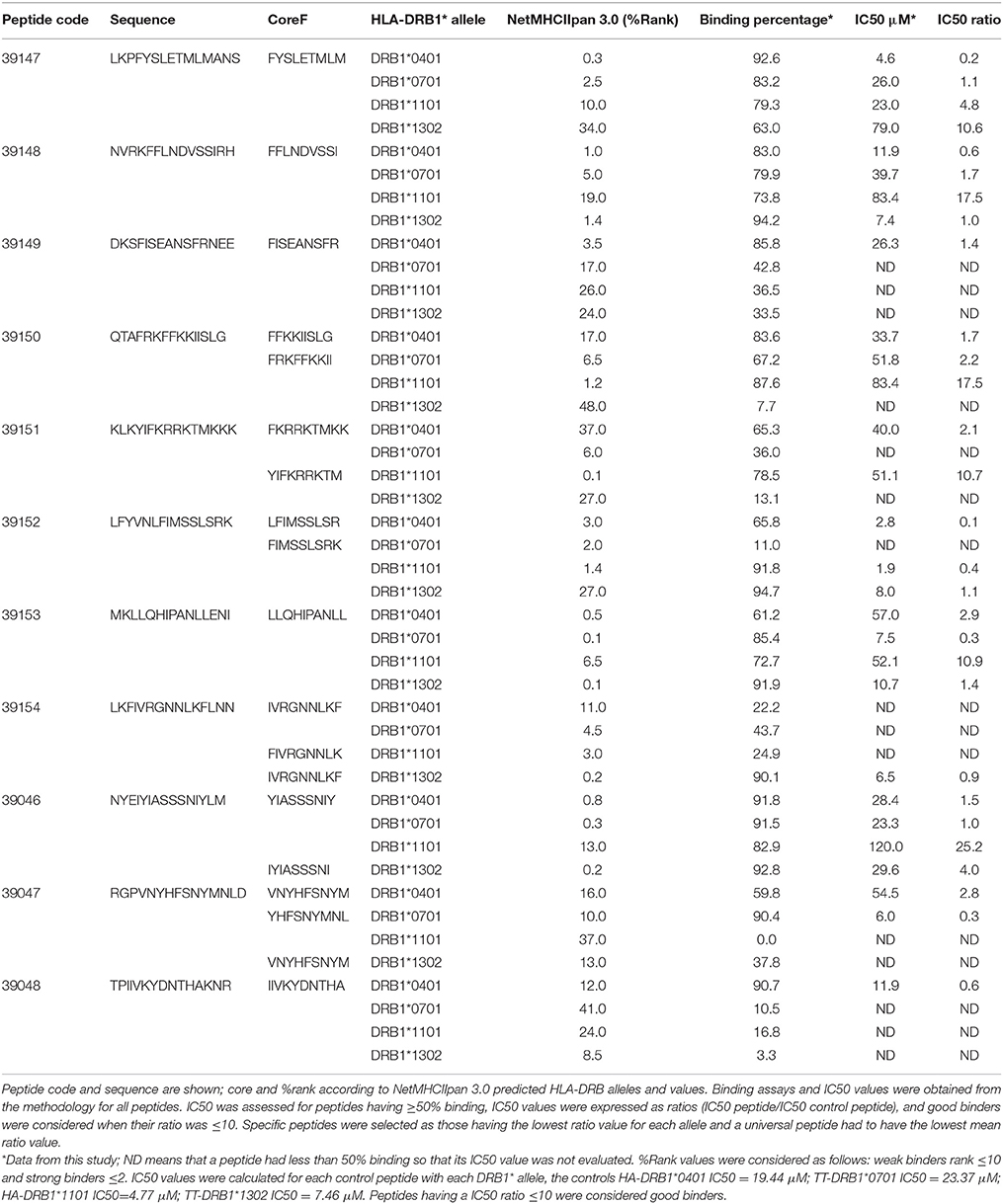

Table 1 gives PvRON2 antigenic epitope prediction results. Eleven epitopes were selected in silico for HLA-DRB1*04, *07, *11, and *13 alleles (3 epitopes for each allele and 2 epitopes for the *07 allele). These epitopes were evaluated in vitro for their ability to bind all alleles of interest; those having greater than 50% binding were carefully chosen as high-binding peptides (Figure 1).

Figure 1. PvRON2 peptides in vitro binding to purified HLA-DRB1* molecules. A cut-off line is shown at 50% binding, used for selecting high-binding peptides for further evaluation of IC50 value. Each plot shows percentage epitope binding to HLA-DRB1* in this study and that for their control peptide.

In vitro results showed that 10/11 (90.9%) peptides bound to the HLA-DRB1*04 allele (73.45% mean binding), being the most promiscuous allele studied; 7/10 (70%) peptides bound to HLA-DRB1*11 (64.47% mean binding); 6/11 (54.5%) of the peptides bound to HLA-DRB1*07 (58.33% mean binding) and HLA-DRB1*13 (56.55% mean binding). Four of the eleven peptides bound to all alleles studied here and were thus considered universal epitopes (39046, 39147, 39148, and 39153). Experimental binding assays and in silico binding predictions agreed in a 70.45% for the alleles studied (Table 1).

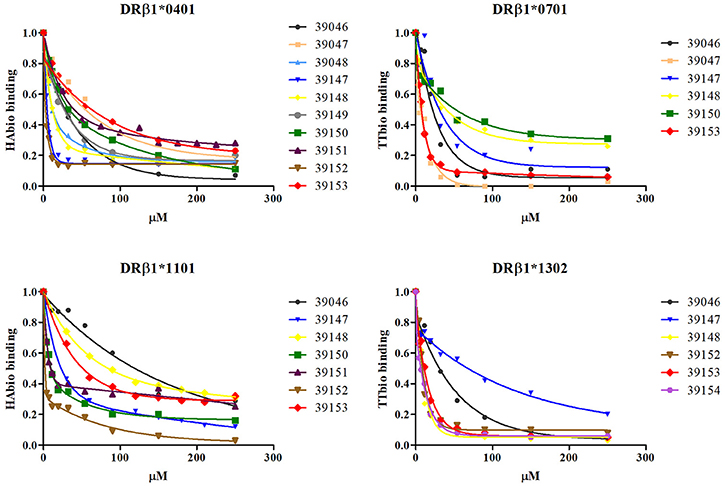

The IC50 value was calculated for all high-binding peptides to select the ones displaying higher affinity. Different peptide concentrations (μM) were used and the point at which 50% of the control peptide was displaced was thus calculated. IC50 μM value was calculated using a second order exponential decay function (Figure 2). IC50 assays demonstrated that epitope 39152 had the lowest IC50 ratio for HLA-DRB1*04 (0.15) and HLA-DRB1*11 (0.4), so it was thus selected as a good epitope for both alleles. Epitope 39047 (0.26) was selected as specific epitope for HLA-DRB1*07 and epitope 39154 (0.88) for HLA-DRB1*13. Of the four universal epitopes, peptide 39153 had the lowest IC50 mean value (Table 1, Figure 2). The selected epitopes were screened for antigenicity according to their HLA-DRB1* binding profile in previously typed patients.

Figure 2. In vitro assays for calculating a PvRON2 peptide's IC50 value. Different epitope concentrations were evaluated for calculating the value at which control peptide was displaced by 50% (using a second order exponential decay function). Each point under the curve represents evaluated epitope concentration-dependent control peptide (μM) binding.

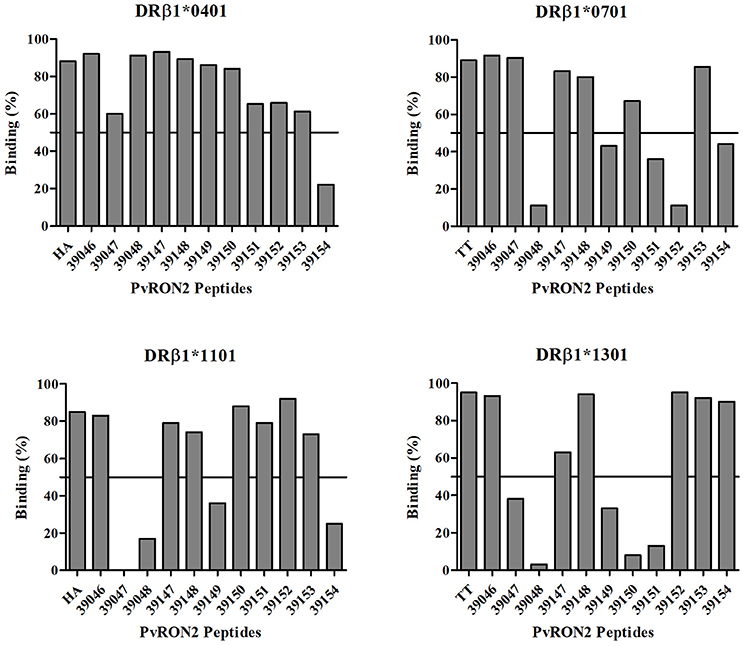

Evaluating T-Cell Response Against Selected Epitopes

The people in the study had to have resided in the area for at least the last 5 years (average 29 years) and have had 1 or multiple episodes of P. vivax malaria, the last episodes dated between 2011 and 2015. It is well known that a naturally-acquired response requires a long period of time and multiple exposures to the parasite (Wipasa et al., 2002). HLA-DRB1* allele distribution for the 79 people here typed is shown in the Supplementary Table 1. Among the alleles of interest, HLA-DRB1*04 had a frequency of 12.66%, HLA-DRB1*07 a frequency of 12.03%, HLA-DRB1*11 a frequency of 8.23% and HLA-DRB1*13 a frequency of 9.49%.

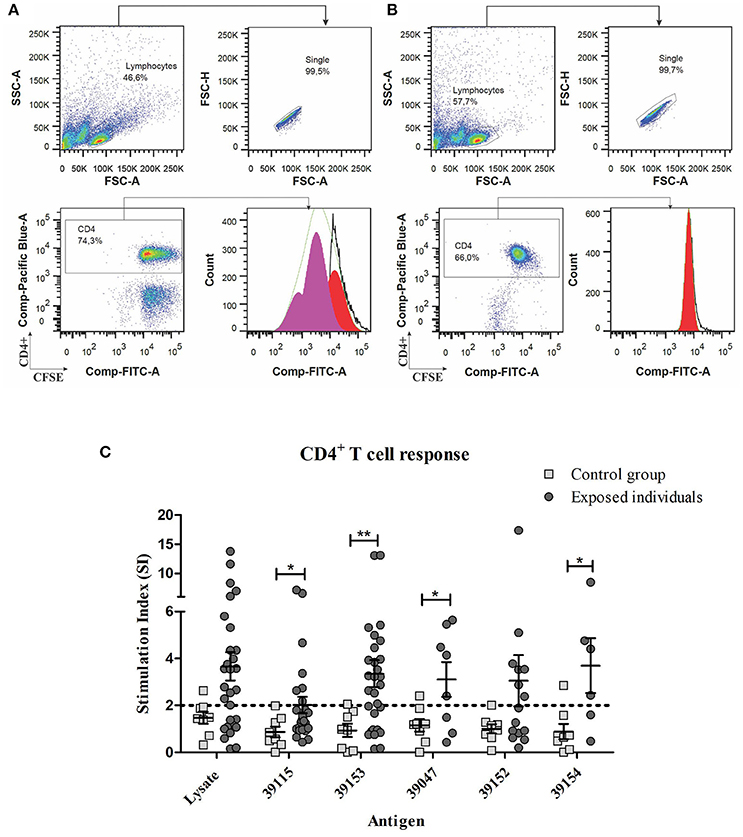

PBMC from individuals exposed to P. vivax infection (and control group) were stimulated with 10 μg/mL PvRON2 peptides and incubated for 5 days to evaluate proliferative response. Both universal epitope 39153 and DRB1* allele-specific peptides induced proliferation (≥2 Stimulation Index) in individuals from endemic areas, whereas there was no proliferation regarding specific peptides for each allele or parasite lysate in the control group (Table 3 and Supplementary Table 2). There were statistically significant differences for universal epitope 39153 (p = 0.0075), DRB1*13-specific peptide 39154 (p = 0.0387) and DRB1*07-specific peptide 39047 (p = 0.0260) between the group of exposed individuals and the control group. This response to the different antigens used in the lymphoproliferation assay, was compared with a Kruskal-Wallis test (with a Dunn's multiple comparison post-test), where no statistically significant differences were found in response to the different peptides.

Low-binding control peptide 39115 showed the lowest proliferative response (SI = 2.018) and was significantly different regarding the control group (p = 0.0289). P. vivax lysate also induced a greater proliferative response in exposed individuals, despite no statistically significant differences were observed when compared to the control group (Figure 3). However, peptide 39115 induced T cell proliferation in 7 of the 29 exposed individuals, despite no binding to HLA-DRB1* was either predicted or observed in vitro. Considering that this peptide is a T epitope from the Pv12 protein as shown by the lymphoproliferation assays, further analyses to assess whether it is being presented by other class II molecules such as HLA-DP or HLA-DQ are worth carrying out.

Figure 3. Gating strategy for the proliferation assays and PBMC proliferative response to PvRON2 epitopes from individuals exposed to P. vivax infection compared to control group. (A) P. vivax-exposed individuals' PBMC stimulated with universal peptide (39153). (B) Non-stimulated P. vivax exposed individuals' PBMCs. (A,B) Upper left plot, selected lymphocyte population (SSC-A vs. FSC-A), upper right plot selection of single cells from lymphocyte population (FSC-H vs. FSC-A). The lower left-hand plot shows gated CFSE label lymphocytes (Comp-FITC-A) for analyzing CD4+ T-cells (Comp-Pacific Blue-A). Lower right-hand plot shows CD4+ lymphocyte proliferation analyzed by FlowJo software (v7.6.5, Ashland, Oregon, USA) using 7 peaks or cell generations. (C) Mann-Whitney and Student's t-tests were used for assessing statistically significant differences between exposed individuals and control group. Universal peptide 39153 (n = 29), DRB1*04 and DRB1*11 peptide 39152 (n = 15), DRB1*07-specific peptide 39047 (n = 8), DRB1*13-specific peptide 39154 (n = 6), low-binding control peptide 39115 (n = 29) and P. vivax lysate (n = 29) responses are shown. The CD4+ cells were labeled with Pacific Blue mouse anti-human CD4 (RPA-T4 clone) antibody. Statistically significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) are shown and data represents the means ± SEM for all values. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.005.

P. vivax lysate also induced a greater proliferative response in exposed individuals; however, no statistically significant differences were observed when compared to control group (Figure 3). The mean SI = 12.47 ± 1.636 SE is for exposed individuals and mean SI = 5.45 ± 1.138 SE for the control group. Despite the SI values of PMBCs stimulated with PHA were significantly higher between exposed individuals and control group (p = 0.0103), 96.6% of exposed individuals and the 100% of control group responded to PHA (data not shown).

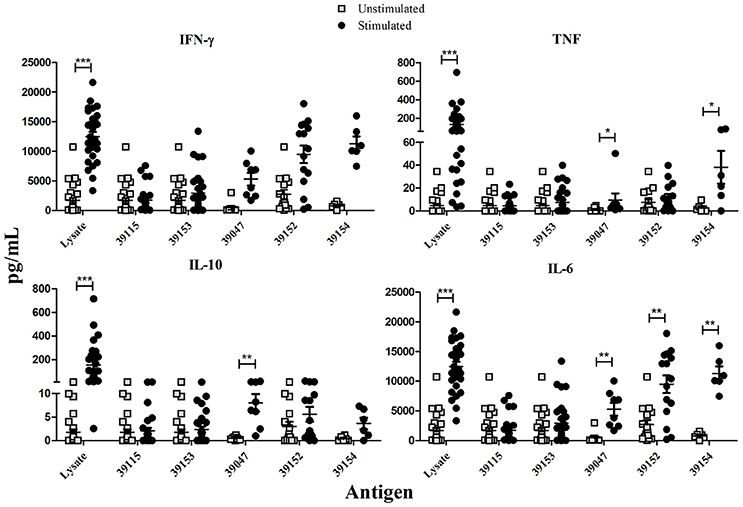

PvRON2 Epitope-Dependent Cytokine Secretion

IFN-γ, TNF (Th1 profile) and IL-10, IL-6 (Th2 profile) production in culture supernatant was quantitatively measured after stimulating PBMCs with peptides selected for HLA-DRB1* by binding assays. P. vivax-lysate and PHA were used as positive controls and unstimulated PBMCs as a baseline. Statistical analysis between unstimulated and stimulated PBMCs from exposed individuals showed that IFN-γ was only significant after stimulation with P. vivax-lysate (p = 0.0001). TNF production was significantly different for peptides 39047 (p = 0.01), 39154 (p = 0.04) and P. vivax-lysate (p = 0.0001). IL-10 had higher production with peptide 39047 (p = 0.001) and P. vivax-lysate (p = 0.0001). IL-6 responses were significantly greater to peptides 39047 (p = 0.01), 39152 (p = 0.0025), 39154 (p = 0.002) and P. vivax-lysate (p = 0.0001) (Figure 4). Cytokine levels were compared with the Kruskal-Wallis test (with a Dunn's multiple comparison post-test) between 39115 and all other peptides in exposed individuals, a significantly higher TNF and IL-6 production was observed for peptide 39154 (p < 0.0001).

Figure 4. Exposed individuals' supernatant culture in vitro cytokine production. Individual data shows the mean value of non-stimulated and PBMCs stimulated with universal epitope (39153), specific epitopes 39047, 39152, and 39154, and P. vivax lysate. IFN-γ, TNF, IL-10, and IL-6 levels were measured by CBA kit; cytokine concentration is expressed in pg/mL. Statistically significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) are shown and data represents the means ± SEM for all values. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005 and ***p < 0.0005.

Control group data was also analyzed; significant differences were found for IFN-γ production after PBMCs had been stimulated with peptides 39047 (p = 0.002), 39154 (p = 0.0006) and P. vivax-lysate (p = 0.0006). IL-6 production was greater after being stimulated with peptides 39152 (p = 0.0006), 39047 (p = 0.002), 39154 (p = 0.01) and P. vivax-lysate (p = 0.0001). This suggests that naïve T-cells and/or other innate cells, such as macrophages, natural killer (NK), natural killer T-cells (NKT) and non-cytotoxic innate lymphoid cells recognized peptides and lysate and produced cytokines (Artis and Spits, 2015) (Supplementary Figure 1).

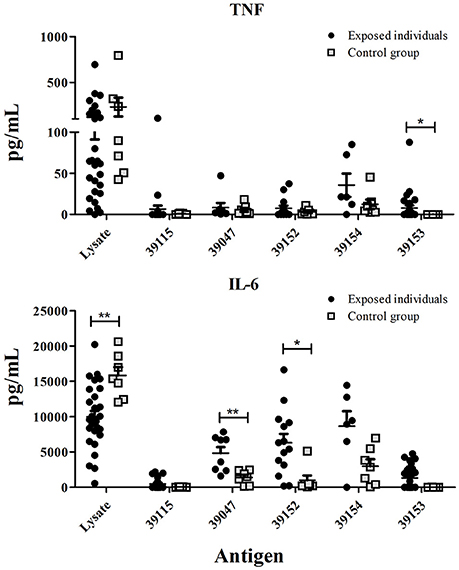

Cytokine levels were compared between exposed individuals and control group, significant differences being found regarding TNF production for epitope 39153 (p = 0.0127). Significant differences were found for epitope 39047 (p = 0.005) and 39152 epitope (p = 0.010) IL-6 production (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Exposed individuals and control group supernatant culture in vitro cytokine production. Individual cytokine values from PBMCs stimulated with universal peptide (39153), specific epitopes 39047, 39152, and 39154, and P. vivax lysate. TNF and IL-6 levels were measured by CBA kit and cytokine concentration is expressed in pg/mL. Statistically significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) are shown and data is the means ± SEM for all values. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.005.

Detecting Antibodies Against P. vivax-Infected RBC by IFA

Naturally-acquired anti-malarial antibodies were detected using Multitest slides (MP Biomedicals) coated with parasitized RBC. The thirty exposed patients' sera reacted against P. vivax but the control group's sera did not. Supplementary Figure 2 shows the fluorescence pattern obtained with these sera.

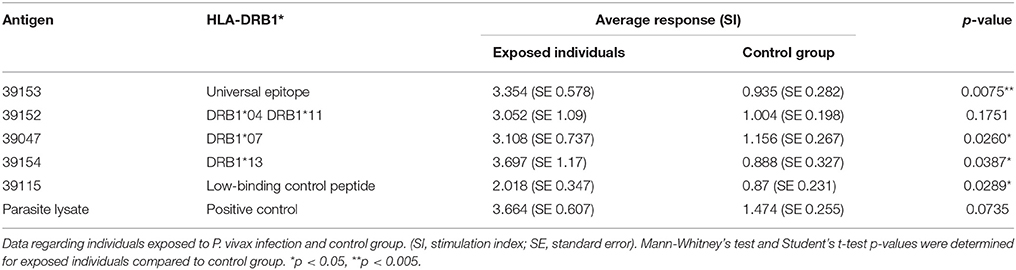

An Analysis of PvRON2 B-Epitope Humoral Immune Response in P. vivax-Exposed Individuals

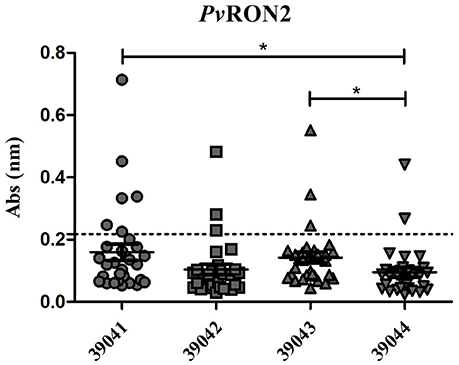

Antibody response against four in silico selected PvRON2 B-epitopes was evaluated in sera from 30 individuals exposed to natural P. vivax infection (Figure 6, Table 2). The highest number of seropositive samples was for the 39041-epitope (6/30, 20% of samples), followed by 39042 and 39043 (3/30, 10% of samples) and 39044 (2/30, 6.6% of samples). Peptides 39041 and 39043 showed the highest mean response (0.1598 and 0.1422, respectively), and significant differences were observed regarding 39044 which had the lowest mean response (0.0949) out of all four peptides. The Kruskal-Wallis test (with Dunn's multiple comparison post-test) was used for statistical analysis, there were significant differences regarding epitope response (p = 0.003). Although there were no statistically significant differences between exposed individuals and control group, there was a tendency for a greater response in the first group (data not shown). rPvGAMA was used as positive control, 70% of samples being seropositive (21/30 samples); significant differences with control group were observed (p = 0.0004) (Supplementary Figure 3).

Figure 6. IgG antibody response against four PvRON2 B-cell epitopes (n = 30). Seropositive samples were those above the cut-off point (0.218, dotted line), calculated as control group's mean plus two standard deviations. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used for analyzing differences between each B-epitopes response in P. vivax-exposed individuals' samples. *p < 0.05.

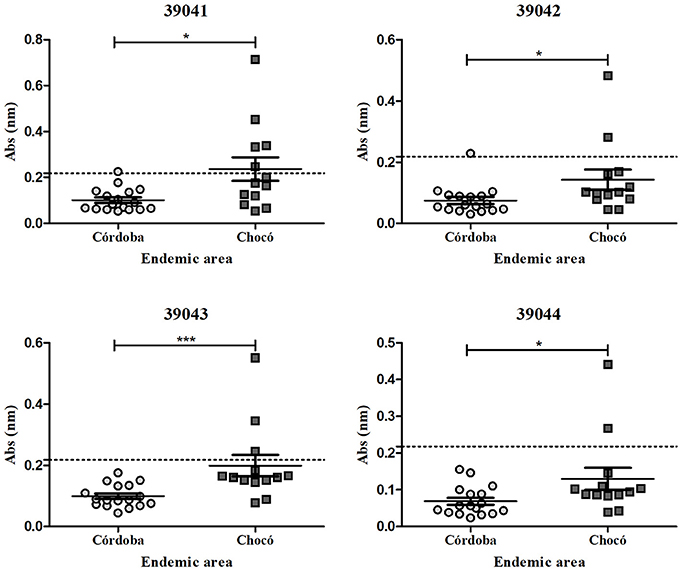

The ELISA results were analyzed by endemic area, showing an evident tendency for a greater response in the samples from the Chocó department compared to the Córdoba department (Figure 7). The Mann-Whitney test gave a significantly higher response for peptides 39041 (p = 0.0135), 39042 (p = 0.0171), 39043 (p = 0.0007) and 39044 (p = 0.0492) in P. vivax-exposed individuals. Samples from Colombia's Chocó (n = 13) and Córdoba (n = 17) departments. From these samples, six reacted positively to at least one PvRON2 B-epitope, where 83% (n = 5) of the samples were from Chocó's department. Positive sera reacted to the four peptides, 83% were from samples from the Chocó department. Although 39041, 39042, and 39044 peptides had no significant differences between exposed individuals from the Chocó and control group, 39043 had a significantly higher response (p = 0.0186). Differences between endemic areas were only observed in response to PvRON2 B-cell epitopes since there were no significant differences between both areas regarding PvGAMA (p = 0.4265), as it was expected to occur when a whole recombinant protein is used as antigen (several epitopes present within it, could be differentially recognized by exposed individuals, and a similar overall response was thus detected). Seropositive samples were selected for evaluating IgG subclasses.

Figure 7. IgG antibody response to PvRON2 B epitopes by endemic area. Significant differences (calculated by Mann-Whitney test) between samples from Colombia's Chocó (n = 13) and Córdoba (n = 17) departments are shown. The dashed line indicates the cut-off point for seropositive samples. *p < 0.05 and ***p < 0.0005.

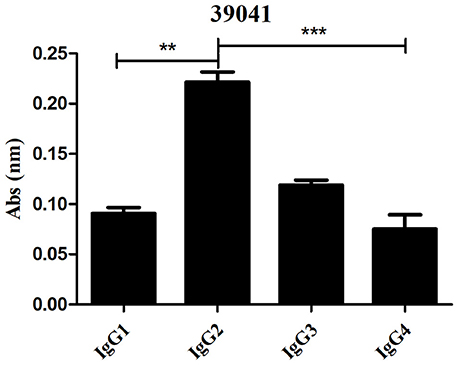

The Prevalence of IgG Subclass Response Against PvRON2 B-Epitopes in Individuals Exposed to Natural P. vivax Infection

Seropositive samples from exposed individuals recognizing B-epitopes were selected for IgG subclass evaluation. Of the four peptides evaluated, only 39041 had significant differences between IgG subclasses (p = 0.0004) while there were no significant differences for the other peptides. 39041 had clear IgG2 predominance regarding other subclasses, having statistically significant differences with IgG1 and IgG4 (the latter having the lowest mean response) (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Evaluating IgG subclass response to the 39041 epitope (n = 6). The Kruskal-Wallis test was used for analyzing differences between each IgG subclass response in P. vivax-exposed individuals' samples. **p < 0.005 and ***p < 0.0005.

Discussion

Developing countries desperately need strategies aimed at preventing malaria (especially that caused by P. vivax), such as approaches for developing specific drugs and protective vaccines which are currently unavailable. Although there are P. vivax vaccines in phases I and IIa (López et al., 2017), they have not induced sterile protection (Bennett et al., 2016). Developing a P. vivax vaccine requires studies analyzing naturally-infected patients' immune response regarding proteins involved in erythrocyte invasion. Several P. vivax vaccine candidates' binding regions have been characterized to date, such as reticulocyte binding proteins (RBPs) (Urquiza et al., 2002), the Duffy binding protein (DBP) (Ocampo et al., 2002), the P. vivax GPI-anchored micronemal antigen (PvGAMA) (Baquero et al., 2017), some proteins from the tryptophan-rich antigen (PvTRAg) family (Zeeshan et al., 2014), merozoite surface protein-1 (PvMSP-1) (RodríGuez et al., 2002) and apical membrane antigen-1 (AMA-1) (Arévalo-Pinzón et al., 2017). Important mediators in AMA-1 erythrocyte binding have also been identified, such as rhoptry neck proteins (RONs), including PvRON5 (Arévalo-Pinzón et al., 2015), PvRON4 (Arévalo-Pinzón et al., 2013) and PvRON2 (Arévalo-Pinzón et al., 2011). RONs have been strongly associated with MJ formation, thereby helping parasite entry into erythrocytes; RON2 is a vaccine candidate since anti-AMA1 and anti-RON2 antibodies can block erythrocyte invasion (Arévalo-Pinzón et al., 2011; Lamarque et al., 2011; Srinivasan et al., 2011; Tyler et al., 2011; Vulliez-Le Normand et al., 2017).

The data presented here has described naturally-acquired T-cell immune responses to PvRON2 high-affinity binding-MHC-II DRB1* peptides in P. vivax-exposed individuals from two endemic areas of Colombia. Certain requirements are involved in protection-inducing vaccine design; for example, the proper antigen presentation by MHC-II and MHC-I molecules to T-cell receptors, so as to induce strong immune responses. MHC class II and I molecules are critical in host–pathogen interactions as they determine host immune response quality. High-affinity peptide-MHCII-TCR binding time or peptide-MHCII complex amount is critical for mounting protective T-cell responses (Blum et al., 2013; Tubo et al., 2013). Post-genomic era bioinformatics tools and reverse vaccinology approaches have drawn scientists' attention, since an individual antigen can be screened from one or several microorganisms and the highest affinity epitopes be determined from these might induce protective immune responses (Sette and Rappuoli, 2010).

This study has analyzed the PvRON2 sequence aa to determine high-binding HLA-DRB1* T-cell epitopes in silico. NetMHCIIpan 3.0 (Andreatta et al., 2015) predicted eleven high-affinity HLA-DRB1* epitopes where at least one epitope bound to one HLADRB1* molecule; this was confirmed by in vitro competition assays using biotin-control peptides. However, some predicted epitopes have not bound to HLA-DRB1*, according to other studies (Bergmann-Leitner et al., 2013), while HLA-DRB1*04 bound to 10/11 peptides here. A previous study has shown a strong naturally-acquired humoral response in HLA-DRB1*04 people living in the Brazilian Amazon against 5/9 recombinant P. vivax proteins (Lima-Junior et al., 2012). HLA-DRB1*04 is one of the most frequently occurring alleles in Colombian Amerindian groups, accompanied by DR2 (DRB1*1602), DR6 (DRB1*1402) and DR8 (DRBl*0802). The patients' blood samples used in this study were mostly taken from Amerindians from Córdoba and Chocó. Tule (5 HLA-DRB1*04 alleles) is the main Amerindian population in Córdoba and the Waunana (4 HLA-DRB1*04 alleles) in the Chocó region, having more diverse DRBl alleles than other groups (Trachtenberg et al., 1996).

Previous studies had suggested that some alleles' over dominance in a population could be due to the spread of advantageous alleles (positive selection) after pathogen-driven selection. This has been shown by Hill et al., in a study of West African alleles (HLA-DRB1*1302-DQB1*0501) which were not present in other racial groups and were associated with protection against severe malaria, i.e., directional selection (Hill et al., 1991).

Several factors (e.g., parasite evasion mechanisms and immune molecule polymorphism) can affect protection-inducing immune responses to malarial parasites and, consequently, malaria vaccine development. Parasite evasion mechanisms include immunodominant antigen polymorphism, antigenic variation and diversion, epitope masking and the smoke-screen strategy. P. vivax and P. ovale have additional escape mechanisms which are mediated by long-lasting hypnozoites, as well as using different erythrocyte invasion pathways (Rénia and Goh, 2016). MHC Class I and II have enormous allele polymorphism and aa sequence variation in the peptide binding region, thereby enabling peptides to bind to different alleles (Blum et al., 2013). Such variability hampers a single epitope-based vaccine against Plasmodium parasites being developed; however, in silico analysis of T- and B-cell epitopes could be useful for identifying vaccine candidates represented by different epitopes which could provide coverage of the whole target population. The exposed patients studied here were grouped according to their HLA-DRB1* to cover the most frequently occurring alleles in the endemic population worldwide, such as HLA-DRB1*04, HLA-DRB1*07, HLA-DRB1*11, and HLA- DRB1*13. Cell-mediated immune responses were investigated based on MHC class II peptide binding specificity and humoral immune responses by detecting antibody levels against linear B-cell epitopes.

Antibodies against P. vivax blood-stage proteins are important elements for blocking RBC invasion (Wipasa et al., 2002); such antibodies thus play an important role in identifying and validating P. vivax vaccine candidates (Soares et al., 1999; Lima-Junior et al., 2008; Storti-Melo et al., 2012; Changrob et al., 2017; Rodrigues-Da-Silva et al., 2017). We confirmed the presence of naturally-acquired humoral responses against four PvRON2 B-epitopes which were recognized by IgG antibodies and subclasses. Low individual PvRON2 B-epitope responder frequency was observed (20% 39041, 10% 39042, 6.6% 39043 and 39044); such low responses have previously been reported for other blood-stage antigens such as PvMSP8. A loss of mean response to a target protein has been observed as time has elapsed when average response has been about ten times greater to recombinant protein than linear epitopes in acute-infection patients (Cheng et al., 2017). This has been associated with short-lived antibodies, due to short-lasting memory responses or parasite-induced B-cell dysregulation (Rénia and Goh, 2016) and parasite genetic variations or in exposed populations.

Antibody response differences against PvRON2 B-cell epitopes between exposed individuals from Chocó (83%) and Córdoba (17%), could be attributed to several factors, including the level of parasitemia and the number of episodes (Druilhe and Pérignon, 1994). The last 3 SIVIGILA reports (2015–2017), showed a higher incidence of P. vivax infection in Chocó regarding Córdoba (Instituto-Nacional-De-Salud, 2017). Other intrinsic factors from the responders such as their HLA, sex, age, psychological stress, nutrition and other infectious diseases could also be involved in such differences (Van Loveren et al., 2001).

Two of the selected B-epitopes (39042 and 39044) were located on an α-helical coiled motif protein and other studies have shown that selected in silico peptides related to these motifs have been recognized by naturally-acquired antibodies and have been immunogenic in mice (Villard et al., 2007; Arévalo-Pinzón et al., 2011); however, 39042 (10%) and 39044 (6.6%) epitopes had the lowest recognition values in our study. 39041 had significant differences in the IgG subclasses analyzed; IgG2 predominated while low IgG4 and IgG1 levels were observed. A predominant IgG2 response and low IgG4 reactivity in previous studies has been associated with P. falciparum infection resistance and clearance, IgG2/IgG4 relationship being associated with a protective role (Aucan et al., 2000). Similar results have been found in PvMSP8 studies recording IgG2 non-cytophilic antibody predominance which has been associated with resistance to P. vivax malaria (Cheng et al., 2017). 39041 has been seen to be immunogenic in mice (Arévalo-Pinzón et al., 2011) and its potentially protective role makes this peptide a pivotal PvRON2 epitope for inclusion in a subunit-based vaccine.

It has been thought that antibodies would be enough to protect against malaria and that T-cells do not play an important role during the erythrocyte stage. Advances in immunology-related knowledge have demonstrated that B-cells must be activated by CD4+ T-helper cells to prompt good humoral responses, thereby inducing cytokine, memory cell and antibody production (Batista and Harwood, 2009; Tubo et al., 2013; Yuseff et al., 2013). The role of exposed patients' T-cell response against PvRON2 high-affinity binding peptides was studied in cytokine proliferation and production assays. Only exposed individuals' PBMC cultures showed proliferation induced by universal and specific binding peptides, suggesting that PvRON2 induced memory T-cells against high-affinity peptides. However, Th1 and Th2 cytokine responses were low, except for IL-6. Low cytokine responses/production have been observed in other studies; Silva-Flannery et al., found that immunization with monomeric peptide did not result in peptide-specific IFN-γ-secreting cell expansion and was not protective. They also reported that the monomeric peptide was less taken up by antigen-presenting cells and was not going through the phagolysosome (Silva-Flannery et al., 2009).

Cytokine production by unexposed individuals' PBMCs against PvRON2 synthetic peptides may have been due to dendritic or macrophages cells priming naïve T-cells and inducing effector T-cell cytokine production; nevertheless, secretion was very low for some of them.

Unlike the other cytokines tested here, IL6 was highly secreted by exposed patients' PBMCs; this was not surprising, since one of IL6's multi-functions is to stimulate hybridoma and plasmacytoma cell growth and help antibody production (Matsuda et al., 1988). IL6, together with IL12 and VDR, have been associated with reduced parasitemia, its severity and gametocytemia clearance in P. vivax-exposed individuals (Sortica et al., 2014). P. vivax lysate-induced cytokine responses in unexposed individuals' PBMCs could be explained by innate immune cell cytokine production, i.e., macrophages, dendritic cells, NK, NKT and naïve T-cells which become effector cells (Stevenson and Riley, 2004). High cytokine induction in healthy individuals compared to P. vivax-exposed individuals might be related to a parasite evasion mechanism for inhibiting effective immune responses able to eliminate the parasite (Rénia and Goh, 2016). Nonetheless, the healthy individuals had not been exposed to P. vivax since immunofluorescence assays did not show their antibodies' reactivity to the parasite.

Taken together, the in silico T-cell and B-cell epitope selection results highlighted two T-cell epitopes (39047 and 39154) and one B-cell epitope (39041) as promising vaccine candidates. Despite the significant differences observed in immune responses evoked in the exposed individuals compared to the control group, overall the responses were relatively low. All selected peptides were conserved among the 11 P. vivax strains which may also explain such low immune responses. This has been demonstrated in P. falciparum studies where conserved high activity binding peptides (HABPs) were poorly antigenic and poorly immunogenic (Patiño et al., 1997; Lougovskoi et al., 1999; Ocampo et al., 2000; Parra et al., 2000; Hensmann et al., 2004). It should be stressed that caution must be taken, since using these 3 promising peptides in a multi-epitope vaccine in their unmodified state would probably mean that they could induce low immunogenicity and not provide long-lasting protection; however, proven approaches have shown that modifying their critical residues should induce a strong and long-lasting protection-inducing immune response (Patarroyo et al., 2010).

HABPs have been seen to be P. falciparum vaccine candidates during the last two decades (Rodriguez et al., 2008); however, they must be modified to make them antigenic and protection-inducing by replacing critical aa with others having the same mass but different polarity (Cifuentes et al., 2008; Patarroyo et al., 2011). Such HABPs can only be used in a tailor-made vaccine targeting a specific HLA-DRB1* endemic population; however, a universal protection-inducing vaccine will require studying other peptides which can bind to other HLA-DRB1* alleles. Future studies should be carried out using modified peptides aimed at assessing immunogenicity and protection-inducing ability in the Aotus experimental model to confirm their suitability as P. vivax vaccine candidates. Likewise, additional peptides should be included to cover all parasite stages, aiming at a 100% protection-inducing, multistage, multi-epitope, minimal subunit-based vaccine.

Author Contributions

CL: designed and performed the experiments, analyzed the data, drafted the manuscript. YY-P: designed and performed the experiments, analyzed the data, drafted the manuscript, designed the figures. DD-A: drafted the manuscript. MEP: critical suggestions regarding the manuscript. MAP: conceiving the work and drafting all versions of the manuscript. All authors have revised the manuscript and approved the version to be submitted.

Funding

This work was financed by the Departamento Administrativo de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (COLCIENCIAS) through grant RC # 0309-2013. CL received support from Colciencias within the framework of the Convocatoria Nacional para Estudios de Doctorado en Colombia (call for candidates # 6172).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the people from Bahía Solano (Chocó) and Tierra Alta (Córdoba) who participated in this study, as well as all the people from healthcare institutions who coordinated sample collection, especially the Centro Médico Cubis in Bahía Solano, Chocó. We would like to thank Jason Garry for translating the manuscript, Natalia Hincapié-Escobar for her technical support, Alejandro Giraldo Escobar for his support with the native community, the Immunotoxicology group (UNAL) for their experimental support, Carlos Fernando Suárez for his critical suggestions and Luis Alfredo Baquero for donating rPvGAMA.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcimb.2018.00156/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Figure 1. Control group supernatant culture in vitro cytokine production. Data individual show the mean value of unstimulated and stimulated PBMC (n = 8) with universal epitope (39153), specific epitopes (39047, 39152, and 39154) and P. vivax lysate. IFN-γ, TNF, IL-10, and IL-6 levels were measured by CBA kit and cytokine concentration is expressed in pg/mL. Statistically significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) are shown and data is the means ± SEM of all values.

Supplementary Figure 2. Immunofluorescence patterns for exposed individuals from Colombia's P. vivax-endemic areas and the control group. The upper panels show one Bahía Solano's exposed individual serum recognition of pRBC. Nuclei were stained with DAPI, the parasite with anti-parasite FITC and then, both were merged. The bottom panels show serum from one non-exposed individual.

Supplementary Figure 3. IgG antibody response against PvGAMA control recombinant protein. Significant differences (calculated by Mann-Whitney test) are shown between samples from exposed individuals and control. The dashed line indicates the cut-off point for seropositive samples.

Supplementary Table 1. Exposed-individuals' HLA-DRB1* allele frequency

Supplementary Table 2. Non-exposed individuals' lymphoproliferation assay using PvRON2 peptides.

Abbreviations

aa, amino acids; AMA, apical membrane antigen; APC, antigen presenting cell; BSA, bovine serum albumin; CBA, Cytometric Bead Array; CFSE, carboxyfluorescein diacetate N-succinimidyl ester; CPD, citrate phosphate dextrose; DAPI, 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylinodole dihydrochloride; DNA, deoxyribonucleic acid; DBP, Duffy binding protein; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; GAMA, GPI-anchored micronemal antigen; gDNA, genomic deoxyribonucleic acid; GPI, glycophosphatidylinositol; HA, hemagglutinin antigen; HABPs, high activity binding peptides; HLA, human leucocyte antigen; HPLC, high-performance liquid chromatography; IEDB, immune epitope database; IFA, indirect immunofluorescence assays; IFN-γ, interferon gamma; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IL, interleukin; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; MJ, moving junction; Mrz, merozoites; MSP, merozoite surface protein; NGS, next generation sequencing; NK, natural killer; NKT, natural killer T-cells; OD, optical density; P. falciparum, Plasmodium falciparum; P. vivax, Plasmodium vivax; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cells; PBS, phosphate buffered saline; PBST, PBS-0.05% Tween 20; pg, picograms; PHA, phytohemagglutinin; pNPP, p-nitrophenylphosphate; pRBC, parasite red blood cells; PV, parasitophorous vacuole; RALP, rhoptry-associated leucine (Leu) zipper-like protein; RBC, red blood cells; RON, rhoptry neck proteins; RPMI, roswell park memorial institute; RT, room temperature; SE, standard error; SEM, standard error of the mean; SI, stimulation index; T. gondii, Toxoplasma gondii; TBS, tris-buffered saline; TBSA, TBS-1% BSA; TCR, T-lymphocyte receptor; Th1, T helper 1; Th2, T helper 2; TMB, 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; TRAg, tryptophan-rich antigen; TT, tetanus toxoid; VDR, vitamin D3 receptor; μM, micromolar.

References

Aikawa, M., Miller, L. H., Johnson, J., and Rabbege, J. (1978). Erythrocyte entry by malarial parasites. A moving junction between erythrocyte and parasite. J. Cell Biol. 77, 72–82. doi: 10.1083/jcb.77.1.72

Andreatta, M., Karosiene, E., Rasmussen, M., Stryhn, A., Buus, S., and Nielsen, M. (2015). Accurate pan-specific prediction of peptide-MHC class II binding affinity with improved binding core identification. Immunogenetics 67, 641–650. doi: 10.1007/s00251-015-0873-y

Arévalo-Herrera, M., Lopez-Perez, M., Medina, L., Moreno, A., Gutierrez, J. B., and Herrera, S. (2015). Clinical profile of Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax infections in low and unstable malaria transmission settings of Colombia. Malar. J. 14:154. doi: 10.1186/s12936-015-0678-3

Arévalo-Herrera, M., Rengifo, L., Lopez-Perez, M., Arce-Plata, M. I., García, J., and Herrera, S. (2017). Complicated malaria in children and adults from three settings of the Colombian Pacific Coast: a prospective study. PLoS ONE 12:e0185435. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0185435

Arévalo-Pinzón, G., Bermúdez, M., Curtidor, H., and Patarroyo, M. A. (2015). The Plasmodium vivax rhoptry neck protein 5 is expressed in the apical pole of Plasmodium vivax VCG-1 strain schizonts and binds to human reticulocytes. Malar. J. 14:1. doi: 10.1186/s12936-015-0619-1

Arévalo-Pinzón, G., Bermúdez, M., Hernández, D., Curtidor, H., and Patarroyo, M. A. (2017). Plasmodium vivax ligand-receptor interaction: PvAMA-1 domain I contains the minimal regions for specific interaction with CD71+ reticulocytes. Sci. Rep. 7:9616. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10025-6

Arévalo-Pinzón, G., Curtidor, H., Abril, J., and Patarroyo, M. A. (2013). Annotation and characterization of the Plasmodium vivax rhoptry neck protein 4 (Pv RON4). Malar. J. 12:356. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-12-356

Arévalo-Pinzón, G., Curtidor, H., Patiño, L. C., and Patarroyo, M. A. (2011). PvRON2, a new Plasmodium vivax rhoptry neck antigen. Malar. J. 10:60. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-60

Artis, D., and Spits, H. (2015). The biology of innate lymphoid cells. Nature 517, 293–301. doi: 10.1038/nature14189

Aucan, C., Traoré, Y., Tall, F., Nacro, B., Traoré-Leroux, T., Fumoux, F., et al. (2000). High immunoglobulin G2 (IgG2) and low IgG4 levels are associated with human resistance to Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Infect. Immun. 68, 1252–1258. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.3.1252-1258.2000

Baquero, L. A., Moreno-Pérez, D. A., Garzón-Ospina, D., Forero-Rodríguez, J., Ortiz-Suárez, H. D., and Patarroyo, M. A. (2017). PvGAMA reticulocyte binding activity: predicting conserved functional regions by natural selection analysis. Parasit. Vectors 10:251. doi: 10.1186/s13071-017-2183-8

Batista, F. D., and Harwood, N. E. (2009). The who, how and where of antigen presentation to B cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9, 15–27. doi: 10.1038/nri2454

Bennett, J. W., Yadava, A., Tosh, D., Sattabongkot, J., Komisar, J., Ware, L. A., et al. (2016). Phase 1/2a trial of Plasmodium vivax malaria vaccine candidate VMP001/AS01B in malaria-naive adults: safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 10:e0004423. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004423

Bergmann-Leitner, E. S., Chaudhury, S., Steers, N. J., Sabato, M., Delvecchio, V., Wallqvist, A. S., et al. (2013). Computational and experimental validation of B and T-cell epitopes of the in vivo immune response to a novel malarial antigen. PLoS ONE 8:e71610. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071610

Blum, J. S., Wearsch, P. A., and Cresswell, P. (2013). Pathways of antigen processing. Ann. Rev. Immunol. 31, 443–473. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032712-095910

Bozdech, Z., Llinás, M., Pulliam, B. L., Wong, E. D., Zhu, J., and Derisi, J. L. (2003). The transcriptome of the intraerythrocytic developmental cycle of Plasmodium falciparum. PLoS Biol. 1:e5. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0000005

Cao, J., Kaneko, O., Thongkukiatkul, A., Tachibana, M., Otsuki, H., Gao, Q., et al. (2009). Rhoptry neck protein RON2 forms a complex with microneme protein AMA1 in Plasmodium falciparum merozoites. Parasitol. Int. 58, 29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2008.09.005

Changrob, S., Han, J. H., Ha, K. S., Park, W. S., Hong, S. H., Chootong, P., et al. (2017). Immunogenicity of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored micronemal antigen in natural Plasmodium vivax exposure. Malar. J. 16:348. doi: 10.1186/s12936-017-1967-9

Cheng, Y., Lu, F., Lee, S. K., Kong, D. H., Ha, K. S., Wang, B., et al. (2015). Characterization of Plasmodium vivax early transcribed membrane protein 11.2 and exported protein 1. PLoS ONE 10:e0127500. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127500

Cheng, Y., Wang, B., Changrob, S., Han, J. H., Sattabongkot, J., Ha, K. S., et al. (2017). Naturally acquired humoral and cellular immune responses to Plasmodium vivax merozoite surface protein 8 in patients with P. vivax infection. Malar. J. 16:211. doi: 10.1186/s12936-017-1837-5

Cifuentes, G., Bermúdez, A., Rodriguez, R., Patarroyo, M. A., and Patarroyo, M. E. (2008). Shifting the polarity of some critical residues in malarial peptides' binding to host cells is a key factor in breaking conserved antigens' code of silence. Med. Chem. 4, 278–292. doi: 10.2174/157340608784325160

Collins, C. R., Withers-Martinez, C., Hackett, F., and Blackman, M. J. (2009). An inhibitory antibody blocks interactions between components of the malarial invasion machinery. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000273. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000273

Counihan, N. A., Kalanon, M., Coppel, R. L., and De Koning-Ward, T. F. (2013). Plasmodium rhoptry proteins: why order is important. Trends Parasitol. 29, 228–236. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2013.03.003

Cowman, A. F., and Crabb, B. S. (2006). Invasion of red blood cells by malaria parasites. Cell 124, 755–766. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.006

Deléage, G., Combet, C., Blanchet, C., and Geourjon, C. (2001). ANTHEPROT: an integrated protein sequence analysis software with client/server capabilities. Comput. Biol. Med. 31, 259–267. doi: 10.1016/S0010-4825(01)00008-7

Doolan, D. L., Southwood, S., Chesnut, R., Appella, E., Gomez, E., Richards, A., et al. (2000). HLA-DR-promiscuous T cell epitopes from Plasmodium falciparum pre-erythrocytic-stage antigens restricted by multiple HLA class II alleles. J. Immunol. 165, 1123–1137. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.1123

Druilhe, P., and Pérignon, J. L. (1994). Mechanisms of defense against P. falciparum asexual blood stages in humans. Immunol. Lett. 41, 115–120. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(94)90118-X

El-Manzalawy, Y., Dobbs, D., and Honavar, V. G. (2017). in silico prediction of linear B-cell epitopes on proteins. Methods Mol. Biol. 1484, 255–264. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-6406-2_17

Fairhurst, R. M., and Dondorp, A. M. (2016). Artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Microbiol. Spectr. 4. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.EI10-0013-2016

Guerra, C. A., Howes, R. E., Patil, A. P., Gething, P. W., Van Boeckel, T. P., Temperley, W. H., et al. (2010). The international limits and population at risk of Plasmodium vivax transmission in 2009. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 4:e774. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000774

Guevara Patiño, J.A., Holder, A. A., Mcbride, J. S., and Blackman, M.J. (1997). Antibodies that inhibit malaria merozoite surface protein−1 processing and erythrocyte invasion are blocked by naturally acquired human antibodies. J. Exp. Med. 186, 1689–1699. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.10.1689

Hammer, J., Bono, E., Gallazzi, F., Belunis, C., Nagy, Z., and Sinigaglia, F. (1994). Precise prediction of major histocompatibility complex class II-peptide interaction based on peptide side chain scanning. J. Exp. Med. 180, 2353–2358. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.6.2353

Hensmann, M., Li, C., Moss, C., Lindo, V., Greer, F., Watts, C., et al. (2004). Disulfide bonds in merozoite surface protein 1 of the malaria parasite impede efficient antigen processing and affect the in vivo antibody response. Eur. J. Immunol. 34, 639–648. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324514

Hill, A. V., Allsopp, C. E., Kwiatkowski, D., Anstey, N. M., Twumasi, P., Rowe, P. A., et al. (1991). Common west African HLA antigens are associated with protection from severe malaria. Nature 352, 595–600. doi: 10.1038/352595a0

Instituto-Nacional-De-Salud (2017). Boletín Epidemiológico Semanal-SIVIGILA. Bogotà, DC: Instituto-Nacional-De-Salud.

Lamarque, M., Besteiro, S., Papoin, J., Roques, M., Vulliez-Le Normand, B., Morlon-Guyot, J., et al. (2011). The RON2-AMA1 interaction is a critical step in moving junction-dependent invasion by apicomplexan parasites. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1001276. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001276

Larsen, J. E., Lund, O., and Nielsen, M. (2006). Improved method for predicting linear B-cell epitopes. Immunome Res. 2:2. doi: 10.1186/1745-7580-2-2

Lima-Junior, J. C., Rodrigues-Da-Silva, R. N., Banic, D. M., Jiang, J., Singh, B., Fabrício-Silva, G. M., et al. (2012). Influence of HLA-DRB1 and HLA-DQB1 alleles on IgG antibody response to the P. vivax MSP-1, MSP-3α and MSP-9 in individuals from Brazilian endemic area. PLoS ONE 7:e36419. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036419

Lima-Junior, J. C., Tran, T. M., Meyer, E. V., Singh, B., De-Simone, S. G., Santos, F., et al. (2008). Naturally acquired humoral and cellular immune responses to Plasmodium vivax merozoite surface protein 9 in Northwestern Amazon individuals. Vaccine 26, 6645–6654. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.09.029

López, C., Yepes-Pérez, Y., Hincapié-Escobar, N., Díaz-Arévalo, D., and Patarroyo, M. A. (2017). What is known about the immune response induced by Plasmodium vivax malaria vaccine candidates? Front. Immunol. 8:126. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00126

Lougovskoi, A. A., Okoyeh, N. J., and Chauhan, V. S. (1999). Mice immunised with synthetic peptide from N-terminal conserved region of merozoite surface antigen-2 of human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum can control infection induced by Plasmodium yoelii yoelii 265BY strain. Vaccine 18, 920–930. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(99)00330-8

Marsh, S. G., Parham, P., and Barber, L. D. (1999). The HLA Factsbook. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Matsuda, T., Hirano, T., and Kishimoto, T. (1988). Establishment of an interleukin 6 (IL 6)/B cell stimulatory factor 2-dependent cell line and preparation of anti-IL 6 monoclonal antibodies. Eur. J. Immunol. 18, 951–956. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830180618

Mongui, A., Angel, D. I., Gallego, G., Reyes, C., Martinez, P., Guhl, F., et al. (2009). Characterization and antigenicity of the promising vaccine candidate Plasmodium vivax 34kDa rhoptry antigen (Pv34). Vaccine 28, 415–421. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.10.034

Moreno-Pérez, D. A., Areiza-Rojas, R., Flórez-Buitrago, X., Silva, Y., Patarroyo, M. E., and Patarroyo, M. A. (2013). The GPI-anchored 6-Cys protein Pv12 is present in detergent-resistant microdomains of Plasmodium vivax blood stage schizonts. Protist 164, 37–48. doi: 10.1016/j.protis.2012.03.001

Moreno-Perez, D. A., Montenegro, M., Patarroyo, M. E., and Patarroyo, M. A. (2011). Identification, characterization and antigenicity of the Plasmodium vivax rhoptry neck protein 1 (Pv RON1). Malar. J. 10:1. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-314

Mueller, I., Galinski, M. R., Baird, J. K., Carlton, J. M., Kochar, D. K., Alonso, P. L., et al. (2009). Key gaps in the knowledge of Plasmodium vivax, a neglected human malaria parasite. Lancet Infect. Dis. 9, 555–566. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70177-X

Nielsen, M., and Lund, O. (2009). NN-align. An artificial neural network-based alignment algorithm for MHC class II peptide binding prediction. BMC Bioinformatics 10:296. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-296

Ocampo, M., Urquiza, M., Guzmán, F., Rodriguez, L. E., Suarez, J., Curtidor, H., et al. (2000). Two MSA 2 peptides that bind to human red blood cells are relevant to Plasmodium falciparum merozoite invasion. Chem. Biol. Drug Design 55, 216–223. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3011.2000.00174.x

Ocampo, M., Vera, R., Eduardo Rodriguez, L., Curtidor, H., Urquiza, M., Suarez, J., et al. (2002). Plasmodium vivax Duffy binding protein peptides specifically bind to reticulocytes. Peptides 23, 13–22. doi: 10.1016/S0196-9781(01)00574-5

Panda, S. K., and Mahapatra, R. K. (2017). In-silico screening, identification and validation of a novel vaccine candidate in the fight against Plasmodium falciparum. Parasitol. Res. 116, 1293–1305. doi: 10.1007/s00436-017-5408-z

Parra, M., Hui, G., Johnson, A. H., Berzofsky, J. A., Roberts, T., Quakyi, I. A., et al. (2000). Characterization of conserved T-and B-cell epitopes in Plasmodium falciparum major merozoite surface protein 1. Infect. Immun. 68, 2685–2691. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.5.2685-2691.2000

Patarroyo, M. A., Bermúdez, A., López, C., Yepes, G., and Patarroyo, M. E. (2010). 3D analysis of the TCR/pMHCII complex formation in monkeys vaccinated with the first peptide inducing sterilizing immunity against human malaria. PLoS ONE 5:e9771. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009771

Patarroyo, M. E., BermúDez, A., and Patarroyo, M. A. (2011). Structural and immunological principles leading to chemically synthesized, multiantigenic, multistage, minimal subunit-based vaccine development. Chem. Rev. 111, 3459–3507. doi: 10.1021/cr100223m

PAHO/WHO (2017). Epidemiological Alert Increase in Cases of Malaria. The Pan American Health Organization [Online]. Available online at: http://www.paho.org

Racanelli, V., Brunetti, C., De Re, V., Caggiari, L., De Zorzi, M., Leone, P., et al. (2011). Antibody Vh repertoire differences between resolving and chronically evolving hepatitis C virus infections. PLoS ONE 6:e25606. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025606

Rénia, L., and Goh, Y. S. (2016). Malaria parasites: the great escape. Front. Immunol. 7:463. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00463

Rieckmann, K., Davis, D., and Hutton, D. (1989). Plasmodium vivax resistance to chloroquine? Lancet 334, 1183–1184.

Rodrigues-Da-Silva, R. N., Soares, I. F., Lopez-Camacho, C., Martins Da Silva, J. H., Perce-Da-Silva, D. S., Têva, A., et al. (2017). Plasmodium vivax cell-traversal protein for ookinetes and sporozoites: naturally acquired humoral immune response and B-cell epitope mapping in Brazilian amazon inhabitants. Front. Immunol. 8:77. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00077

Rodriguez, L. E., Curtidor, H., Urquiza, M., Cifuentes, G., Reyes, C., and Patarroyo, M. E. (2008). Intimate molecular interactions of P. falciparum merozoite proteins involved in invasion of red blood cells and their implications for vaccine design. Chem. Rev. 108, 3656–3705. doi: 10.1021/cr068407v

RodríGuez, L. E., Urquiza, M., Ocampo, M., Curtidor, H., Suárez, J., Garciía, J., et al. (2002). Plasmodium vivax MSP-1 peptides have high specific binding activity to human reticulocytes. Vaccine 20, 1331–1339. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(01)00472-8

Saravia, C., Martinez, P., Granados, D. S., Lopez, C., Reyes, C., and Patarroyo, M. A. (2008). Identification and evaluation of universal epitopes in Plasmodium vivax Duffy binding protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 377, 1279–1283. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.10.153

Sette, A., and Rappuoli, R. (2010). Reverse vaccinology: developing vaccines in the era of genomics. Immunity 33, 530–541. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.09.017

Silva-Flannery, L. M., Cabrera-Mora, M., Dickherber, M., and Moreno, A. (2009). Polymeric linear peptide chimeric vaccine-induced antimalaria immunity is associated with enhanced in vitro antigen loading. Infect. Immun. 77, 1798–1806. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00470-08

Soares, I. S., Da Cunha, M. G., Silva, M. N., Souza, J. M., Del Portillo, H. A., and Rodrigues, M. M. (1999). Longevity of naturally acquired antibody responses to the N- and C-terminal regions of Plasmodium vivax merozoite surface protein 1. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 60, 357–363. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.60.357

Solihah, B., Winarko, E., Hartati, S., and Wibowo, M. E. (2017). “A systematic review: B-cell conformational epitope prediction from epitope characteristics view,” in 2017 3rd International Conference on Science and Technology-Computer (ICST) (Yogyakarta: IEEE), 93–98.

Sortica, V. A., Cunha, M. G., Ohnishi, M. D., Souza, J. M., Ribeiro-Dos-Santos, Â. K., Santos, S. E., et al. (2014). Role of IL6, IL12B and VDR gene polymorphisms in Plasmodium vivax malaria severity, parasitemia and gametocytemia levels in an Amazonian Brazilian population. Cytokine 65, 42–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2013.09.014

Srinivasan, P., Baldeviano, G. C., Miura, K., Diouf, A., Ventocilla, J. A., Leiva, K. P., et al. (2017). A malaria vaccine protects Aotus monkeys against virulent Plasmodium falciparum infection. NPJ Vaccines 2:14. doi: 10.1038/s41541-017-0015-7

Srinivasan, P., Beatty, W. L., Diouf, A., Herrera, R., Ambroggio, X., Moch, J. K., et al. (2011). Binding of Plasmodium merozoite proteins RON2 and AMA1 triggers commitment to invasion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 13275–13280. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110303108

Stern, L. J., and Calvo-Calle, J. M. (2009). HLA-DR: molecular insights and vaccine design. Curr. Pharmaceut. Design 15, 3249–3261. doi: 10.2174/138161209789105171

Stevenson, M. M., and Riley, E. M. (2004). Innate immunity to malaria. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4, 169–180. doi: 10.1038/nri1311

Storti-Melo, L. M., Da Costa, D. R., Souza-Neiras, W. C., Cassiano, G. C., Couto, V. S., Póvoa, M. M., et al. (2012). Influence of HLA-DRB-1 alleles on the production of antibody against CSP, MSP-1, AMA-1, and DBP in Brazilian individuals naturally infected with Plasmodium vivax. Acta Trop. 121, 152–155. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2011.10.009

Sturniolo, T., Bono, E., Ding, J., Raddrizzani, L., Tuereci, O., Sahin, U., et al. (1999). Generation of tissue-specific and promiscuous HLA ligand databases using DNA microarrays and virtual HLA class II matrices. Nat. Biotechnol. 17, 555–561. doi: 10.1038/9858

Trachtenberg, E., Keyeux, G., Bernal, J., Rhodas, M., and Erlich, H. (1996). Results of expedition humana. HLA 48, 174–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1996.tb02625.x

Tubo, N. J., Pagán, A. J., Taylor, J. J., Nelson, R. W., Linehan, J. L., Ertelt, J. M., et al. (2013). Single naive CD4+ T cells from a diverse repertoire produce different effector cell types during infection. Cell 153, 785–796. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.007

Tyler, J. S., Treeck, M., and Boothroyd, J. C. (2011). Focus on the ringleader: the role of AMA1 in apicomplexan invasion and replication. Trends Parasitol. 27, 410–420. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2011.04.002

Udomsangpetch, R., Kaneko, O., Chotivanich, K., and Sattabongkot, J. (2008). Cultivation of plasmodium vivax. Trends Parasitol. 24, 85–88. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2007.09.010

Urquiza, M., Patarroyo, M. A., Marí, V., Ocampo, M., Suarez, J., Lopez, R., et al. (2002). Identification and polymorphism of Plasmodium vivax RBP-1 peptides which bind specifically to reticulocytes. Peptides 23, 2265–2277. doi: 10.1016/S0196-9781(02)00267-X

Van Loveren, H., Van Amsterdam, J. G., Vandebriel, R. J., Kimman, T. G., Rümke, H. C., Steerenberg, P. S., et al. (2001). Vaccine-induced antibody responses as parameters of the influence of endogenous and environmental factors. Environ. Health Perspect. 109, 757–764. doi: 10.1289/ehp.01109757

Vargas, L. E., Parra, C. A., Salazar, L. M., Guzmán, F., Pinto, M., and Patarroyo, M. E. (2003). MHC allele-specific binding of a malaria peptide makes it become promiscuous on fitting a glycine residue into pocket 6. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 307, 148–156. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(03)01129-X

Villard, V., Agak, G. W., Frank, G., Jafarshad, A., Servis, C., Nébié, I., et al. (2007). Rapid identification of malaria vaccine candidates based on alpha-helical coiled coil protein motif. PLoS ONE 2:e645. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000645

Vulliez-Le Normand, B., Saul, F. A., Hoos, S., Faber, B. W., and Bentley, G. A. (2017). Cross-reactivity between apical membrane antgen 1 and rhoptry neck protein 2 in P. vivax and P. falciparum: a structural and binding study. PLoS ONE 12:e0183198. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183198

Wang, P., Sidney, J., Kim, Y., Sette, A., Lund, O., Nielsen, M., et al. (2010). Peptide binding predictions for HLA DR, DP and DQ molecules. BMC Bioinformatics 11:568. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-568

Wipasa, J., Elliott, S., Xu, H., and Good, M. F. (2002). Immunity to asexual blood stage malaria and vaccine approaches. Immunol. Cell Biol. 80, 401–414. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2002.01107.x

Yuseff, M.-I., Pierobon, P., Reversat, A., and Lennon-Duménil, A.-M. (2013). How B cells capture, process and present antigens: a crucial role for cell polarity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 13, 475–486. doi: 10.1038/nri3469

Zeeshan, M., Tyagi, R. K., Tyagi, K., Alam, M. S., and Sharma, Y. D. (2014). Host-parasite interaction: selective Pv-fam-a family proteins of Plasmodium vivax bind to a restricted number of human erythrocyte receptors. J. Infect. Dis. 211, 1111–1120. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu558

Keywords: Plasmodium vivax, PvRON2, HLA-DRB1 typing, antigenicity, synthetic peptide, epitope, cellular and humoral response

Citation: López C, Yepes-Pérez Y, Díaz-Arévalo D, Patarroyo ME and Patarroyo MA (2018) The in Vitro Antigenicity of Plasmodium vivax Rhoptry Neck Protein 2 (PvRON2) B- and T-Epitopes Selected by HLA-DRB1 Binding Profile. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 8:156. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00156

Received: 18 December 2017; Accepted: 24 April 2018;

Published: 15 May 2018.

Edited by:

Jorge Enrique Gómez Marín, University of Quindío, ColombiaReviewed by:

Pedro Ismael Da Silva Junior, Instituto Butantan, BrazilSara Maria Robledo, Universidad de Antioquía, Colombia

Copyright © 2018 López, Yepes-Pérez, Díaz-Arévalo, Patarroyo and Patarroyo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Manuel A. Patarroyo, mapatarr.fidic@gmail.com

Carolina López

Carolina López Yoelis Yepes-Pérez

Yoelis Yepes-Pérez Diana Díaz-Arévalo