Mind the Gap: The New Special Educational Needs and Disability Legislation in England

- School of Education, University of Roehampton, London, UK

With the introduction of the Children and Families Act 2014, changes in the process of assessment and identification of children in need of special support in England and Wales have been introduced. These changes are regarded as the most significant in two decades, with consequent implications for service provision. In this paper, we suggest that there is a gap between the theoretical approach to disability portrayed in the new policy and many of the practical changes consequently introduced. To examine this mismatch, a sequence of arguments is presented, as a critical analysis of the approach introduced by the new policy, in light of a framework recognized worldwide for conceiving and classifying disability – the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health for Children and Youth (ICF-CY). Although the ICF-CY is not mentioned in the new policy for special educational needs and disability, possible links between the two are presented, with implications for service provision.

Introduction

A considerable shift has recently been observed in the policy regulating the provision of special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) services for children and young people in England. In theory, this is a substantial change, as it entails a considerable move toward a new conceptualization of SEND, with implications for professional practice and service provision for vulnerable children and young people. However, despite this philosophical shift, the new policy documents regulating SEND provision in England – the Children and Families Act 2014 (Part 3) (Department for Education, 2014a) and the Special Educational Needs and Disability Code of Practice 2014 (Department for Education, 2014b) – do not explicitly present a theoretical model underpinning its innovative approach. Moreover, specific and practical guidelines for the regulation of professional practice regarding the implementation of the proposed changes have not been as yet sufficiently provided – for example, more systematic guidelines for the development of high quality Education Health and Care plans (EHC plans) are needed. Therefore, in this paper, we suggest that there is a gap between the theoretical approach to SEND in the new policy and some of its implications for service provision. To support this argument, we offer a critical analysis of the new approach introduced by the Children and Families Act 2014 and the new SEND Code of Practice, which leads to recommendations for the implementation of the EHC assessment and planning process purported by law in England.

This analysis is based on the argument that the new approach to SEND provision is, in some respects, theoretically aligned with biopsychosocial and bioecological models of development and disability, which also form the basis for the development of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health for Children and Youth (ICF-CY) (WHO, 2007). The World Health Organization (WHO) endorsed the ICF-CY in 2007 as the universal language to describe disabilities in children and young people (WHO, 2007). The ICF-CY may provide a theoretical model that adequately frames the approach to special education provision conveyed in the Children and Families Act 2014 Part 3 and in the SEND Code of Practice 2014. Additionally, the ICF-CY may provide the classification system that can systematically support the development and monitoring of EHC plans. In the first part of this paper, we present an overview of the ICF-CY model and of the changes that have been introduced in the SEND provision system in England. We also explore the arguments supporting the assumption that the ICF-CY model is closely aligned with the new SEND policy and should, therefore, be integrated in the SEND provision system. In the second part of this paper, we introduce the ICF-CY classification system in more detail and provide systematic suggestions as to how the ICF-CY can be applied to support the development and monitoring of EHC plans, as required by law.

This paper does not aim to provide a critical analysis of the Children and Families Act 2014 Part 3 as a whole, but focuses specifically on the lack of congruence observed between the principles introduced by it and the lack of an evidence-based framework to actually implement them. The changes introduced by the new policy imply the action of an integrated system, articulating education, health, and social care services. However, this contradicts other aspects of the discourse presented in the policy documents themselves, namely, a discourse that is vague in relation to the definition of SEND; in fact, according to Norwich (2014) (p. 418) “Though the alignment of special educational needs with diagnosed medical conditions is not made explicitly (…) in the Green Paper or in the new Special Educational Needs Code of Practice, it is implicit in the language used and by the silence about an interactive causal model of special educational needs.” In other words, while the new policy claims to present a holistic, biopsychosocial, and multidimensional approach to disability, in practice, it still restricts service provision to actions that are based on an essentially medical model of SEND, according to the Equality Act 2010, still the policy document that professionals needs to be aware of when referring to various SEND (Cheminais, 2014). The introduction of the ICF-CY by trained specialists in the EHC assessment and planning may help to overcome some of these contradictions. In fact, according to Norwich (2014) (p. 419), “there has been little UK interest in the use of the ICF for educational purposes, suggesting a gap in contemporary conceptions of how to think about and develop appropriate educational identification systems.” This paper addresses this dearth of debate around contemporary views of identification in education and introduces the potentialities of the ICF-CY model and classification system to special educational needs provision in England.

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health for Children and Youth

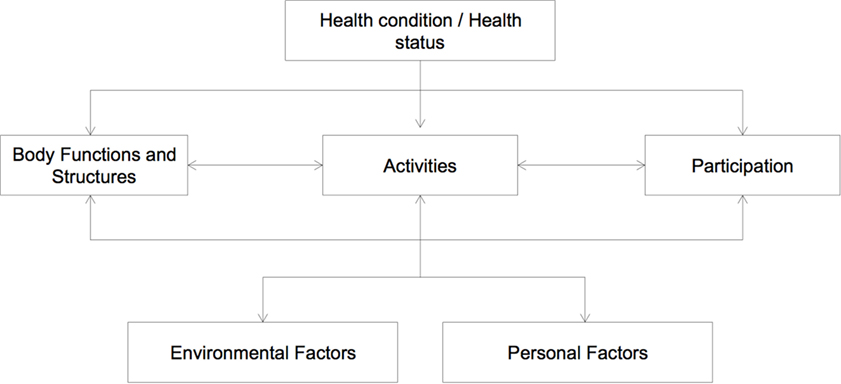

In 2007, the WHO published the International Classification of Functioning Disability and Health for Children and Youth (ICF-CY), which followed the publication of its adults’ version (ICF) in 2001. The publication of the ICF/ICF-CY by the WHO complemented the WHO Family of International Classifications (WHO-FIC), which includes the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, now in its 10th edition (WHO, 2010). The two classification systems – the ICF-CY and the ICD-10, are based on two different approaches to disability: while the ICD-10 is based on a medical model approach by which symptoms are categorized into diagnosis, the ICF-CY is based on a functional approach to disability; therefore, the ICF-CY is not based on a medical model approach, as the ICD-10 is, and it is also not based on a social approach to disability; in fact, the social model has contested the medical model view of disability, by moving the accountability source from the individual and the body to the society; from this point of view, disability exists because society is not prepared to accommodate diversity (Simeonsson, 2006). The ICF-CY model provides the third way of looking at special needs which is similar to the approach proposed by Kristiansen et al. (2008). This third approach provides a viewpoint between the medical model and the social model of disability, as it considers that the source of disability is the complexity of individual and social factors interacting to result in a unique individual functioning profile (Simeonsson, 2006). From this point of view, the cause of the SEND is not the impairment in individual bodily functions per se, or the limitations that the society imposes on individual functioning (as advocated by the social model), but it is the dynamic conjugation of all these factors (WHO, 2007). For this reason, instead of providing a taxonomy for diagnosis, the ICF-CY classification system provides a thorough list of aspects of functioning covering all life dimensions. These functioning dimensions are organized into three main components: body functions and structures, activities and participation, and environmental factors. As illustrated in Figure 1, the ICF-CY model proposes that within a specific health condition (which may or may not be a diagnosis, and should therefore be regarded as health status) there are aspects related to body functions, the activities in which we participate and the environments in which we are embedded, which influence our functioning profile at one particular moment in time. A child or young person with SEND is someone whose overall functioning is compromised due to a specific profile in which these factors interact with each other in a way that restricts the child’s overall participation (WHO, 2007). The WHO definition of participation is broad, and it means involvement in life situations; thus, every time the child is restricted from participating in a life situation/routine that she/he should be able to engage in, a problem of functioning may occur and intervention may be necessary, even if we are not in face of a conventional disability.

Figure 1. The ICF-CY model (WHO, 2007).

Changes in the SEN Provision in England and Wales: The Children and Families Act and the SEND Code of Practice 2014

The changes in the SEND provision recently introduced in England and Wales through the Children and Families Act and the new SEND Code of Practice 2014 (Department for Education, 2014a,b) aim to instigate the most radical change in the system since 1981, when the statements of SEND were first implemented (Cheminais, 2014; Norwich, 2014). Many of the changes have been gradually implemented since 2010, with the beginning of the coalition government, and in 2011 with the publication of the SEND Green Paper (Department for Education, 2011). The Green Paper aimed to “reform radically the new statutory SEN assessment” (Department for Education, 2011, p. 7), by gradually replacing statements of SEN with a more holistic document and by implementing “pathfinders” to explore the community resources that can best support the development of integrated assessments (Department for Education, 2011).

Some of the changes implemented by the new SEND Code of Practice and the Children and Families Act Part 3 include the definition of the concept of SEND; the emphasis on multi-agency working to achieve an integrated, holistic assessment of the child or young person; the definition of a wider age range for the provision of SEN services (birth to 25 years of age); the emphasis on a child-centered approach, in which the voices of the children and families themselves should be taken into account when planning their assessment and intervention; an increased focus on child participation and quality of life in adulthood and removal of barriers to learning; the replacement of the previous statements of SEND with Education, Health and Care (EHC) plans, as a result of the collaborative and integrative assessment process. These changes are explicitly presented in both the Children and Families Act 2014 and in the new SEND Code of Practice. The argument that the ICF-CY model and classification system can facilitate the implementation of the new policy guidelines will be presented with a particular focus on the changes mentioned earlier.

According to the Children and Families Act and the new SEND Code of Practice 2014, a child or young person has SEND if a learning difficulty is present that calls for special education provision services to be put in place to support their learning and participation. The criteria for deciding whether this is the case are twofold: the difficulties observed are significantly greater than the majority of others of the same age and there is an objective disability that is preventing or hindering the child from using educational facilities that are generally used by others of the same age (Department for Education, 2014c). The Equality Act 2010 is still considered the policy document that defines the range of disability types that, according to the SEND Code of Practice 2014, professionals need to be aware of. Professionals must be aware of these types of disability, have enhanced knowledge or specialist knowledge about these types of disability, depending on whether they only interact occasionally with children with SEND, they need to adapt teaching strategies for these children, or they are advising and supporting those with enhanced knowledge, such as the Special Educational Needs coordinators (SENCOs) (Cheminais, 2014). These types of disability specified in the Equality Act 2010 are sensory impairments, physical impairments, developmental conditions, progressive diseases, mental health conditions and mental diseases, HIV, and cancer (Cheminais, 2014). The SEND Code of Practice also highlights that teachers are responsible and accountable for the progress of the pupils in their class, even when there is support and specialist staffing allocated to work with children with SEND. This accountability implies good knowledge of the range of disabilities that can be most frequently observed, and knowing the best strategies to support children with these types of SEND so as to remove barriers to learning (Department for Education, 2014c). However, we argue that the terminology associated with the types of SEN that teachers should be aware of, considering the SEND Code of Practice and the Equality Act, contradicts the holistic and integrative model proposed as a whole in the Children and Families Act. The types of SEN regarded in the Equality Act 2010 are still very much medical model based and do not fully address the concept of participation in society that the new policy proposes nor the child-centered approach advocated. This argument will be further discussed in this paper.

Multi-agency working is required in order to develop an integrated holistic assessment of the child and to recognize children’s needs in all areas of life, from education to health and social care. Professionals from different backgrounds should, therefore, work together in close collaboration so as to produce the single integrated document that describes the child’s needs and strengths holistically – the EHC plan (Department for Education, 2014c). Although the idea of multi-agency working for the provision of integrated services is regarded as invaluable (Hodkinson and Vickerman, 2009; Elliott-Johns et al., 2013; Protheroe et al., 2013), the current SEND Code of Practice guidelines on how to actually implement this collaborative effort lack specificity and allocate responsibilities for setting up integrated services to the local authorities (LAs), NHS England, their partners, and schools:

“Local authorities, NHS England and their partner CCGs must make arrangements for agreeing the education, health and social care provision reasonably required by local children and young people with SEN or disabilities. In doing so they should take into account provision being commissioned by other agencies, such as schools, further education colleges and other education settings” (Department for Education, 2014c, p. 40). (…) “Joint commissioning must also include arrangements for: securing EHC needs assessments, securing the education, health and care provision specified in EHC plans, and agreeing Personal Budget” (Department for Education, 2014c, p. 40).

We suggest that these guidelines could be put into practice more systematically if an evidence-based system was implemented as a framework for the changes suggested, such as the ICF-CY. The same model can also support the implementation of a service provision system that is child-centered approach, considers the views of the families, and systematically supports the development of integrated EHC plans.

The Contradiction between Listening to Children’s Voices and the Definition of Special Educational Needs

Part 3 of the Children and Families Act 2014 starts by defining the role of LAs in supporting and involving children and young people by listening to their voices, as well as to the wishes and feelings of their parents, so that they are fully able to participate in the decisions affecting their lives in an informed manner. The importance of listening to children’s views about their SEND and factors affecting their well-being has been highlighted in both policy documents and research (Gray et al., 2006; Georgeson et al., 2014). Recent research has also provided interesting data on factors affecting the sense of well-being of children with SEND, according to their own views. Children mentioned being able to participate, having good friends, family factors, anxiety related to performance in school, coping strategies/resilience, and personal growth and development as factors that could critically affect their well-being (Palikara et al., 2009; Palikara, 2010; Foley et al., 2012). These studies provide evidence of two very important issues for children with disabilities, namely (a) that being included and fully participating in society is more than being able to learn, as it also encompasses other dimensions of life such as relationships and a sense of fulfillment, and (b) that their full participation is often restricted by the environment around them, so that our interventions should move away from targeting the children’s ability to learn, and focus more on the environment.

Acknowledging children’s voices is therefore the first and very important step toward full inclusion, but there seems to be a gap between what the law states LAs should do (listening to children and their families’ voices) and the provided definition of SEND, which does not consider this invaluable data obtained from studies conducted about the children’s perspectives. Moreover, there is a contradiction between the advocated model’s focus on participation and well-being, and the SEND Code of Practice’s definition of less than expected progress as a mismatch in attainment of children with SEND when compared with their peers. In fact, the very definition of SEND previously presented does not include all the dimensions of life that were mentioned by children themselves as essential for a sense of inclusion, since it overemphasizes the importance of learning and school performance. Therefore, we argue that a better definition of SEND could be achieved if the ICF-CY model had been considered as the theoretical framework for the new law. The concept of Participation provided by the ICF-CY model matches the views of children with SEND about well-being: being included and participating is being “involved in (a variety of) life situations” (WHO, 2007, p. 16). These include more than learning and applying knowledge, such as the relationships established with others, and internal factors, such as coping and resilience, as well as environmental factors that can facilitate or restrict participation.

Consideration of the multidimensional aspect of inclusion would have been useful in implementing the holistic approach that the new policy attempts to introduce by integrating different services (education, health, and social care). From the ICF-CY point of view, children with SEND are those whose full participation is restricted, whether because of their internal difficulties (such as learning or any other diagnosis), or the environment in which they are embedded, or the combination of both (WHO, 2007). This definition implies that services have to be brought together for an integrative approach to inclusion, without an overemphasis on education and learning, or on specific types of disability that are medical model based, but rather with a focus on overall participation. In fact, the SEND Code of Practice 2014 underlines that “In practice, individual children or young people often have needs that cut across all these areas and their needs may change over time” (Department for Education, 2014c, p. 97) when referring to the high-incidence types of SEND, thus contradicting the need for these categories; a more holistic, functional system, and worldwide recognized system, such as the ICF-CY, can account for this overlap between different functioning difficulties and can support monitoring over time. A child with a diagnosable or conventional type of SEND may be participating in society, while a child without a diagnosable SEND or who does not specifically “fit” into any of the predefined SEND types may need considerable support to achieve participation.

The Integration of Services

One positive development in the new framework is the consideration that there should be holistic service provision for children and young people with SEND, integrating education with health and social services in order to promote children’s full participation and well-being. Interdisciplinary approaches to disability have been consistently recommended as the most effective way of promoting full inclusion, representing an essential pillar of the ICF-CY theoretical framework (Clarke et al., 2011; Pan et al., 2015). The main structure of the ICF-CY itself (body functions and structures, activities and participation, and environmental factors) is based on the assumption that we cannot separate education, health, and social care issues when describing the functioning profile of a child, as suggested by the biopsychosocial and bioecological approaches to development. The biopsychosocial approach may be conceptualized within the systemic theories of development, which according to Engel (1977) – its first proponent – serve as an organizing framework for explaining complex phenomena comprising several levels of hierarchical interaction: a change in one part of the system affects the whole system; therefore, a change in psychosocial aspects of a child’s life may affect her overall functioning (including not only body functions but also environmental aspects).

The adoption of this framework in conceiving health and human functioning can largely improve communication between different disciplines in health care, according to Engel (1977). The ICF-CY model systematically enables the translation of this perspective into practice. Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological model of development considers that at any particular moment in time, the developmental status is the result of the dynamic interaction between the person (with his/her biological features) and the contexts in which that person is embedded, whether these are more proximal (for example, within microsystemic settings) or more distal (macrosystemic settings) (Bronfenbrenner, 2005); this theory of dynamic interaction between the individual and the surrounding systems in a given moment in time is designated by person-process-context-time model. Any developmental disturbance, delay, disability, or need would be the result of a unique dynamic interaction between individual and biological features and aspects of the environment, in one or more of the systems in which the individual is embedded (Bronfenbrenner, 2005). The ICF-CY as a classification system enables the systematic mapping of individual characteristics and the influence of the environment (coded with the environmental factors component), which results in specific forms of Participation – coded with the activities and participation component (WHO, 2007; Anaby et al., 2013). These environmental aspects can be situated in a more proximal or distal position, but still exert some influence on the child’s functioning, in line with the bioecological model of development.

Accordingly, services should work in an integrated manner, as interdisciplinary teams that address a whole profile of abilities and disabilities in context. Theoretically, the three core services purported in the Children and Families Act 2014 that should work collaboratively are clearly aligned with the ICF-CY structure – body functions and structures (health), activities and participation (education), and environmental factors (social care). These three mutually interact to characterize individual functioning and well-being, as illustrated in Figure 1. Based on this theoretical match, we argue that all the conditions are in place for the ICF-CY to be regarded as the classification system that can support the implementation of this integrative approach. Moreover, in spite of advocating for holistic service provision, the SEND Code of Practice does not provide any specific guidelines on how to implement this interdisciplinary service provision.

Local Offers and the Documentation of Environmental Factors

While the recommendation for the integration of services can be regarded as a positive change in the new policy, there are not specific enough guidelines on how to achieve this interdisciplinary EHC assessment. In fact, local authorities (LAs) must cooperate with governing bodies of schools, national health services, and social services, but no specific directions are provided on how to achieve these aims. Each LA must also make public its “Local Offer” (Department for Education, 2014a, p. 26), explicitly informing stakeholders about education, health, and social care options in its vicinity. We argue that the ICF-CY classification system could be used to present the Local Offer in each LA by matching each service with the environmental factors component of the classification.

It is important to underline that the ICF-CY is a recognized universal system to systematically classify environmental factors that may represent facilitators or barriers to children’s participation and well-being (WHO, 2007). The ICF-CY codes describe the support of systems, services, and policies in education, health, and social care, as well as the work developed by specific professionals in each of these subcomponents (WHO, 2007). Any parent or caregiver seeking more information about various Local Offers would have a better way of comparing between them if they were all classified using the same system – the ICF-CY common language. Therefore, we argue that not only should the conditions for the implementation of the ICF-CY as a classification system to support the EHC assessment process be put in place but also a striking need for a common system to describe Local Offers across different LAs. Moreover, according to the Children and Families Act 2014, once the EHC plan has been agreed to be issued by the LA, parents can request a personal budget to be developed regarding the provision of SEND services for their child (Department for Education, 2014c). Using a common system such as the ICF-CY to describe the different services to be provided for all children could enable a fairer definition of personal budgets, since the ICF-CY system would enable a rigorous comparison between cases.

The EHC Needs Assessment and the Development of EHC Plans

One of the most significant changes of the new law is the replacement of the statements of SEN with EHC plans. The EHC plans result from the EHC needs assessment conducted by the LA (Department for Education, 2014a). The documentation of children’s needs is of particular importance for the systematic implementation and monitoring of interventions delivered in schools (Shriner and Destefano, 2003). Therefore, the needs assessment must be accurate, interdisciplinary as proposed by the EHC model itself, and timely. However, “Calling the new plans education, health and care plans is also misleading, as they are basically education plans where health and social care needs are included in so far as they relate to special educational needs. They are not, for example, about health provision unrelated to special educational needs” (Norwich, 2014, p. 416). We argue that the appropriate introduction of the ICF-CY as a tool to support the development of EHC plans is critical in addressing this issue. The law specifically describes what the EHC plan should include. However, it leaves the how to be decided by the LA, with no indication of any guidelines or recommended practices for interdisciplinary assessment and subsequent development of EHC plans. We argue that the ICF-CY should be established as the classification system to guide the EHC needs assessment and to support the development of the EHC plans in interdisciplinary teams.

The ICF-CY is not based on diagnosis, as other classifications do (such as the International Classification of Diseases and Health-Related Problems – ICD – also published by the WHO), but rather it focuses on functioning profiles, which illustrate a unique combination of education, health, and social care issues in each child (WHO, 2007). Therefore, we suggest that the application of the ICF-CY for this purpose would facilitate the development of an integrated system of assessment. The availability of functioning dimensions to be classified and coded across all life domains in the ICF-CY means that professionals can address all of those domains equally, not overemphasizing body functions and structures in relation to environmental factors, for instance, which often happens when designing intervention plans that are not based on a holistic system (Castro et al., 2014a,b). Additionally, having EHC plans in which the functioning profiles of the children are described in a holistic and common language enables comparison of data on children’s well-being and participation across schools, LAs, and countries, especially considering that the ICF-CY has been implemented by law in other nations, such that its language is already being extensively applied (Sanches-Ferreira et al., 2013; Hwang et al., 2014). One of the research priorities set out in the new policy is to compare England’s SEND approach to those adopted by other countries (Department for Education, 2014a).

The Children and Families Act also requires that the outcomes to be achieved are specified in the EHC plan. Similarly, in the absence of guidelines on how to define outcomes, it is likely that we will observe various outcomes being specified, from very specific to very vague, which are not comparable across EHC plans and LAs. It may also happen that outcomes will be focused on attainment and/or types of SEND, contradicting the philosophical approach of a holistic assessment, as explained previously. When using the ICF-CY classification system to develop functioning profiles for each child, the outcomes to be achieved could be selected from these functioning profiles and, thus, documented in a universal language and classification system. Education, health, and social care provisions that are required to be included in the plan may also be described using the ICF-CY environmental factors component, thus enabling the comparison of provision across plans. Because the ICF-CY system enables the monitoring of functioning profiles over time (Lollar and Simeonsson, 2005; WHO, 2007), its use to support the development of EHC plans would also facilitate reviews, reassessment, and transition planning.

The Utility of the International Classification of Functioning Disability and Health for Children and Youth for the Development of EHC Assessment and EHC Plans

Those who have worked with children with SEND will have experienced the observation that two children with the same diagnosis can often have completely different needs and behavioral profiles, and this has also been observed empirically (Lollar and Simeonsson, 2005; Castro and Pinto, 2015). Moreover, the presence of a diagnosis does not necessarily mean that the child has SEND, and similarly, there are symptoms that do not fit into a single diagnosis. In fact, comorbidity of symptoms often hinders the definition of clear diagnoses, especially in early childhood, in which development is fast and not always predictable (Gillberg, 2010). However, the absence of a clear diagnosis or type of SEND does not mean that the child does not need support to fully participate. For this reason, a classification system is needed to address functioning in addition to diagnosis. The ICF-CY was developed to address this issue (WHO, 2007). From the ICF-CY perspective, the source of the child’s needs is not the diagnosis itself, but the complexity of functions, participation restrictions, and environmental barriers and facilitators that characterize each child’s functioning profile (WHO, 2007). Similarly, children who are not included are not participating in their natural settings at their full potential.

The introduction of such a theoretical orientation in conceiving SEND could probably help to clarify the current absence of agreement about the definition of inclusion in England (Norwich, 2014). In fact, while the concept of SEND is still medically based, the possibility of having children who are not provided with adequate and individualized support is still open, as they may not fit into one of the predefined categories. Diagnosis is important and should therefore be considered as a starting point to intervention, but not as the ultimate goal of the assessment, as this leaves behind more individualized and invaluable information for intervention purposes (Castro and Pinto, 2015). For example, a child with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is very likely to present difficulties at the level of social interaction, communication, and to have restricted and repetitive thought, because these are the main criteria for this diagnosis (American Psychiatric Association, 2003). However, there is evidence that the nature of the difficulties in the domain of social interaction may vary substantially when compared with another child of the same age with ASD (Castro and Pinto, 2015), thus leading to very different intervention strategies to be adopted. Therefore, for educational purposes and early intervention in particular, we need to move beyond the diagnostic category and address the individual functioning profile of the child. This is particularly important in early years, when development changes rapidly and diagnosis is particularly challenging and often inherently diffuses (Gillberg, 2010).

The ICF-CY enables this detailed documentation of particular functioning domains. For this reason, it is regarded both as a theoretical model for disability and as a classification system (WHO, 2007). Another advantage of the ICF-CY, proposed by the WHO, is that it constitutes a common language across professionals with different areas of knowledge (as it uses common codes to classify functioning) and, therefore, has the potential to support multi-agency working. In fact, once all professionals are familiarized with the system, documents and intervention plans developed in any service or country can be systematically comparable (WHO, 2007).

The ICF-CY provides specific codes to describe numerous dimensions of functioning within body functions and structures, activities and participation, and within the environmental factors component (WHO, 2007). In addition to the codes used in these components, a universal qualifier follows each code. The universal qualifier scale provides a way of describing the magnitude of the functioning difficulty in each dimension or code, ranging from 0 – absence of functioning problem – to 4 – total functioning problem. Therefore, the code d710.3 from Activities and Participation, for instance, represents a severe difficulty (0.3) in basic interpersonal interactions (d710) and the code b1301.1 represents a mild difficulty (0.1) in motivation functions (b1301).

In the case of the environmental factors component, the ICF-CY enables the description of whether one particular factor is restricting or facilitating the child’s functioning and participation. For example, the code e410 + 3 indicates that the attitudes of the immediate family (e410) are a substantial facilitator (+3) of the child’s participation, while the code e550.3 indicates that the legal services, systems and policies (e550) are a substantial barrier (0.3) to the child’s participation (WHO, 2007). We propose that in the new System for SEND provision in England, the body functions and the activities and participation codes could be used to document the children’s SEND in the EHC plan. Similarly, the environmental factors’ codes could be applied to describe the environmental influence contextual features on the child’s participation or to document the Local Offers across LAs, using a common language.

By analyzing sample, EHC plans that have been provided through various sources as an attempt to provide guidelines for its development, and it is possible, in our view, to identify some common problems. Plans do not seem to be comparable as, for example, they do not use the same language when describing the children’s needs and strengths. Having comparable data are important for LA and national monitoring for special needs provision. Some plans do not include all dimensions of life, often focusing only on physical well-being and communication (which is again a return to a medical model approach and is not representative of the approach proposed in the new law). Some plans specify the various professionals that have been involved in the EHC process and how they have contributed, often with the indication of “report only.” This is indicative that an integrated assessment is not being conducted and that multi-agency working is not fully achieved. Finally, EHC plans do not always clearly present a link between the description of the children’s strengths and needs and the intervention that is suggested.

To overcome these needs, we propose that a series of steps should be adopted to ensure that the basic principles of the new law are put into practice, by introducing the ICF-CY classification system in the EHC assessment process. First, a bottom-up approach to the introduction of the ICF-CY should be adopted. The use of the ICF-CY requires training (WHO, 2007). Local initiatives and trials are necessary to gather evidence of how the ICF-CY can, in practice, support the EHC assessment process and development of EHC plans, as well as evidence about the views of professionals and parents about its usefulness. Second, this bottom-up approach needs to be supported by a clear investment in cutting-edge research in this field. In England, the Department for Education published a paper on SEND: Research Priorities and Questions, in which clear research orientations are defined: research on how to measure performance of children, on methods used to identify children with SEND, comparability of the English system to that of other countries, the impact of different types of support on pupils’ outcomes, and the impact of multi-agency working among others, are all needed (Department for Education, 2014c). These research priorities can be put into practice in light of the ICF-CY by investigating how the classification can contribute to measurement and identification and impact on participation. Third, experts on the ICF-CY model and classification system should be allocated to test its utility in local predefined contexts, to train professionals on how to use it, and to gather the aforementioned and much needed research evidence. Trained professionals should include all those contributing to EHC plans development, from all three sectors. Finally, the results of this bottom-up approach should be integrated in specific, integrated, and systematic guidelines that generalize the use of the ICF-CY classification system to support the development of EHC plans, thus contributing toward a real shift in SEND provision toward a more integrative, holistic, and contemporary approach to disability and inclusion.

Final Considerations

The ICF-CY system has some recognized limitations. In spite of its detailed system for the coding of functioning, the ICF-CY leaves open the question of which criteria we should use to attribute the universal qualifier of a particular functioning dimension; how to distinguish between a mild and a moderate problem? The answer to this question is twofold. First, we must think of the ICF-CY as a classification tool, not as a measurement tool. Its purpose is to describe, not to measure. Second, and consequently, new measurements are necessary, based on the ICF-CY functioning dimensions, in order to provide a rigorous and valid assessment. Additionally, extant measures need to be mapped onto the ICF-CY classification system (Simeonsson et al., 2003; WHO, 2007; Simeonsson and Lee, 2013), so that the current assessment outcomes obtained through widely used measurements can be translated into the ICF-CY universal language. Some tools that are ICF-CY based have already been developed, such as the Participation and Environment Measure for Children and Youth – PEM-CY (Coster et al., 2011). Extensive research has also been conducted on mapping extant measurements with items of currently used measurements for child development, health, and disability to the ICF-CY functioning dimensions. Relevant examples include the autism diagnostic observation schedule (ADOS; Lord et al., 2011) and the schedule of growing skills (SGS II; Bellman et al., 1996), which have been mapped to the classification’s items (Castro et al., 2013, 2014a,b).

Other limitations of the ICF-CY have been pointed out since its publication. Although the classification model is described as personal factors, such as age, gender, and ethnicity, for instance, there are no codes to classify these demographic variables (WHO, 2007). Such demographic data should be recorded in customary formats, as has been done in many other areas of service provision for children, and furthermore, that classifying personal factors with universal codes could potentially lead to a misuse of personal and idiosyncratic attributes (Simeonsson et al., 2014). The problem of agreement between users of the ICF-CY has been highlighted systematically since its publication in numerous research studies, with results showing that often agreement is not very high, and can vary substantially from fair levels of agreement to good and very good (Grill et al., 2007; Castro et al., 2014a,b). For this reason, we recommend the development of specific guidelines concerning how to implement the ICF-CY classification system in a way that minimizes these constraints.

In spite of the aforementioned and recognized limitations of the ICF-CY, its theoretical match with the new SEN policy in England and Wales makes it a useful framework to support the implementation of the changes introduced by this law in a more systematic and rigorous way. Both the ICF-CY model and the new policy clearly propose a multi-disciplinary holistic approach to disability and SEND. Moreover, the introduction of the ICF-CY in the new system could help to conceal the previously mentioned contradiction: while the new policy claims to purport a holistic approach to special needs, it is still very much linked to types of SEND and diagnostic categories.

Author Contributions

Both SC and OP have written the whole paper in collaboration, and the ideas provided are the result of shared reflection. SC has a background in psychology and special educational needs and particular expertise on the ICF. OP has a background in educational psychology and special educational needs.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2003). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. APA.

Anaby, D., Hand, C., Bradley, L., DiRezze, B., Forhan, M., DiGiacomo, A., et al. (2013). The effect of the environment on participation of children and youth with disabilities: a scoping review. Disabil. Rehabil. 35, 1589–1598. doi:10.3109/09638288.2012.748840

Bellman, M., Longam, S. and Aukett, A. (1996). The Schedule of Growing Skills II. London: GL Assessment.

Castro, S., Coelho, V., and Pinto, A. (2014a). Identification of functional domains in developmental measures: an ICF-CY analysis of Griffiths developmental scales and schedule of growing skills II. Dev. Neurorehabil. 19, 231–237.

Castro, S., Pinto, A., and Simeonsson, R. J. (2014b). Content analysis of Portuguese individualized education programmes for young children with autism using the ICF-CY framework. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 22, 91–104. doi:10.1080/1350293X.2012.704303

Castro, S., Ferreira, F., Dababnah, S., and Pinto, A. (2013). Linking autism measures with the ICF-CY: functionality beyond the borders of diagnosis and interrater agreement issues. Dev. Neurorehabil. 16, 321–331. doi:10.3109/17518423.2012.733438

Castro, S., and Pinto, A. (2015). Matrix for assessment of activities and participation: measuring functioning beyond diagnosis in young children with disabilities. Dev. Neurorehabil. 18, 177–189. doi:10.3109/17518423.2013.806963

Cheminais, R. (2014). Special Educational Needs for Qualified and Trainee Teachers: A Practical Guide to the New Changes. New York, NY: Routledge.

Clarke, S., Sloper, P., Moran, N., Cusworth, L., Franklin, A., and Beecham, J. (2011). Multi-agency transition services: greater collaboration needed to meet the priorities of young disabled people with complex needs as they move into adulthood. J. Integr. Care 19, 30–40. doi:10.1108/14769011111176734

Coster, W., Bedell, G., Law, M., Khetani, M. A., Teplicky, R., Liljenquist, K., et al. (2011). Psychometric evaluation of the participation and environment measure for children and youth. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 53, 1030–1037. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2011.04094.x

Department for Education. (2011). Support and Aspiration: A New Approach to Special Educational Needs and Disability: a Consultation, Vol. 8027. London: The Stationery Office.

Elliott-Johns, S. E., Wideman, R., Black, G. L., Cantalini-Williams, M., and Guibert, J. (2013). Developing multi-agency partnerships for early learning: seven keys to success. Learn. Landscapes 7, 146–169.

Engel, G. L. (1977). The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science 196, 129–136. doi:10.1126/science.847460

Foley, K. R., Blackmore, A. M., Girdler, S., O’Donnell, M., Glauert, R., Llewellyn, G., et al. (2012). To feel belonged: the voices of children and youth with disabilities on the meaning of wellbeing. Child Indic. Res. 5, 375–391. doi:10.1007/s12187-011-9134-2

Georgeson, J., Porter, J., Daniels, H., and Feiler, A. (2014). Consulting young children about barriers and supports to learning. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 22, 198–212. doi:10.1080/1350293X.2014.883720

Gillberg, C. (2010). The ESSENCE in child psychiatry: early symptomatic syndromes eliciting neurodevelopmental clinical examinations. Res. Dev. Disabil. 31, 1543–1551. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2010.06.002

Gray, P., Bullen, P., Duckett, L., Leyden, S., Pollard, I., and Skelton, R. (2006). National Audit of Support, Services and Provision for Children with Low Incidence Needs. London: Department for Education and Skills.

Grill, E., Mansmann, U., Cieza, A., and Stucki, G. (2007). Assessing observer agreement when describing and classifying functioning with the international classification of functioning, disability and health. J. Rehabil. Med. 39, 71–76. doi:10.2340/16501977-0016

Hodkinson, A., and Vickerman, P. (2009). Key Issues in Special Educational Needs and Inclusion. London: SAGE.

Hwang, A. W., Liao, H. F., Chen, P. C., Hsieh, W. S., Simeonsson, R. J., Weng, L. J., et al. (2014). Applying the ICF-CY framework to examine biological and environmental factors in early childhood development. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 113, 303–312. doi:10.1016/j.jfma.2011.10.004

Kristiansen, K., Vehmas, S., and Shakespeare, T. (eds) (2008). Arguing about Disability: Philosophical Perspectives. New York, NY: Routledge.

Lollar, D. J., and Simeonsson, R. J. (2005). Diagnosis to function: classification for children and youths. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 26, 323–330. doi:10.1097/00004703-200508000-00012

Lord, C., Rutter, M., Dilavore, P. and Risi, S. (2001). Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS). WPS Publishers.

Norwich, B. (2014). Changing policy and legislation and its effects on inclusive and special education: a perspective from England. Br. J. Spec. Educ. 41, 403–425. doi:10.1111/1467-8578.12079

Palikara, O. (2010). The Impact of Specific Language Impairment on the Educational and Socio-Emotional Competence of Adolescents: Factors Supporting Positive Adjustment [Doctoral Dissertation]. London: University of London, Institute of Education.

Palikara, O., Lindsay, G., and Dockrell, J. E. (2009). Voices of young people with a history of specific language impairment (SLI) in the first year of post-16 education. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 44, 56–78. doi:10.1080/13682820801949032

Pan, Y. L., Hwang, A. W., Simeonsson, R. J., Lu, L., and Liao, H. F. (2015). ICF-CY code set for infants with early delay and disabilities (EDD Code Set) for interdisciplinary assessment: a global experts survey. Disabil. Rehabil. 37, 1044–1054. doi:10.3109/09638288.2014.952454

Protheroe, S., Debelle, G. G., Holden, C., and Powell, J. (2013). Health and social care: will they work together for children now? Arch. Dis. Child. 98, 556–557. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2013-303859

Sanches-Ferreira, M., Simeonsson, R. J., Silveira-Maia, M., Alves, S., Tavares, A., and Pinheiro, S. (2013). Portugal’s special education law: implementing the international classification of functioning, disability and health in policy and practice. Disabil. Rehabil. 35, 868–873. doi:10.3109/09638288.2012.708816

Shriner, J. G., and Destefano, L. (2003). Participation and accommodation in state assessment: the role of individualized education programs. Except. Child. 69, 147–161. doi:10.1177/001440290306900202

Simeonsson, R. J. (2006). “Appendix C: defining and classifying disability in children,” in Workshop on Disability in America: A New Look, eds M. J. Field, A. Jette, and L. Martin (Washington, DC: National Academy Press), p. 67–87.

Simeonsson, R. J., and Lee, A. S. (2013). “The ICF-CY: a universal taxonomy for psychological assessment,” in The Oxford Handbook of Child Psychological Assessment (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 202.

Simeonsson, R. J., Leonardi, M., Lollar, D., Bjorck-Akesson, E., Hollenweger, J., and Martinuzzi, A. (2003). Applying the international classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF) to measure childhood disability. Disabil. Rehabil. 25, 602–610. doi:10.1080/0963828031000137117

Simeonsson, R. J., Lollar, D., Björck-Åkesson, E., Granlund, M., Brown, S. C., Zhuoying, Q., et al. (2014). ICF and ICF-CY lessons learned: Pandora’s box of personal factors. Disabil. Rehabil. 36, 2187–2194. doi:10.3109/09638288.2014.892638

WHO. (2007). International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health for Children and Youth. Genève: WHO.

Keywords: 2014 SEND Code of Practice, disability, England, ICF, ICF-CY

Citation: Castro S and Palikara O (2016) Mind the Gap: The New Special Educational Needs and Disability Legislation in England. Front. Educ. 1:4. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2016.00004

Received: 13 May 2016; Accepted: 13 October 2016;

Published: 01 November 2016

Edited by:

Tony Cline, University College London, UKReviewed by:

Marie Coppola, University of Connecticut, USAGarry Squires, University of Manchester, UK

Copyright: © 2016 Castro and Palikara. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Susana Castro, susana.castro@roehampton.ac.uk

Susana Castro

Susana Castro Olympia Palikara

Olympia Palikara