95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 21 April 2017

Sec. Leadership in Education

Volume 2 - 2017 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2017.00012

The gender of school leaders makes a difference in career paths, personal life, and characteristics of workplace. There is additional evidence that men and women are appointed or elected to lead different kinds of educational jurisdictions. Even if those differences did not exist, equitable access to leadership positions for people of different backgrounds would make this an important issue. This article reports gender-related findings from the American Association of School Administrators 2015 Mid-Decade Survey. Findings confirm many of the trends in research on the superintendency over the past 15 years. The profiles of women superintendents are becoming more like their male counterparts. Both men and women appear to be less mobile than in the past. Men and women are spending about the same time as teachers before becoming superintendents, women and men appear to experience stress similarly, and women are receiving mentoring much more than in the past. There are few data to support the beliefs that women superintendents, more than men, are limited by family circumstance although this survey sheds no light on perspectives of women aspirants. This survey also confirms that there are a variety of paths to the position providing opportunities for women who have not necessarily had the typical teacher/principal/central office administrator trajectory. Nevertheless, significant differences still exist. Most important is that men are still four times more likely than women to serve in the most powerful position in education, and both women and men of color are still grossly underrepresented.

Since early in the twentieth century, the American Association of School Administrators (AASA) has conducted regular surveys to document the state of the position of superintendent. The 2015 Mid-Decade Survey used 50 items including new questions to collect data on experiences that are relevant to the gender of the incumbents: all items were examined for their relevance to gender.

The results of this survey are important and useful in a number of ways. First, they allow us to track changes in the proportionality of women superintendents in a field that has historically been disproportionate. While 75% of teachers are women, female superintendent representation is nowhere near that level. Problems that are documented are more likely to be solved than those that are not tracked. Lack of female representation is a problem not only because of fairness and equity but also because diversity brings improvements in leadership and learning. More women superintendents are good for children.

A random sample of 9,000 superintendent email addresses were selected by a vendor and queried with an online survey link February 2015. From that group, 845 respondents identified their gender. The number of responses was large enough for reliable statistical analysis; however, the response rate was low. Because the authors were not involved in the data collection, we were unable to determine generalizability through non-response bias tests.

Analysis included chi-square tests, correlation, t-tests, and ANOVA. The interpretation of the analysis is focused on illuminating gender-specific differences in leadership and its context. The findings contrast and compare 2015 responses to earlier research on women superintendents in the representation of women in the superintendency, career paths, district demographics where women serve, barriers and challenges, reasons for leaving the superintendency, and women’s perspectives on leadership.

A significant portion of research on women superintendents to date concentrates on historical accounts of women who have achieved the superintendency. Traditionally, these studies provide a descriptive demographic analysis of the number of women who have served in the position of school superintendent (Björk, 2000).

The position of superintendent first appeared in Buffalo, NY, USA and Louisville, KY, USA in 1837 (Grieder et al., 1969). By 1850, 13 large cities had established the occupation of superintendent of schools (Kowalski, 2005). Since the creation of those first positions, the superintendency has been defined and institutionalized as men’s work (Shakeshaft, 1989; Blount, 1998; Grogan, 1999; Skrla, 1999; Skrla et al., 2000). This stereotype was perpetuated by the perceived skills of the position. The role of superintendent emphasized management, and the goal was to improve overall school system operations by prioritizing time and efficiency (Tyack and Hansot, 1982). Highlighting the managerial aspect of the position kept the position almost exclusively male-dominated for decades.

Moreover, as gender equality became a national issue in the 1970s, some concluded that there were significantly more women in leadership positions—possibly due to women as building principals. In 1971, the AASA Research Study identified that only 1.3% of all superintendent positions in the United States were held by women (Knezevich, 1971) and, a decade later, the percentage had actually decreased to 1.2% (Cunningham and Hentges, 1982). These percentages pointed to a problem for school leadership and corrected the myth that women were in charge. Through the 1970s and 1980s, this crisis was highlighted in the pioneering research on women in educational administration (Gross and Trask, 1976; Schmuck, 1976, 1980; Shakeshaft, 1979, 1987, 1989; Biklen and Brannigan, 1980; Hansot and Tyack, 1981; Arnez, 1982; Ortiz, 1982; Marshall, 1984, 1985; Shakeshaft et al., 1984; Biklen and Shakeshaft, 1985; Bell, 1988; Edson, 1988). The authors challenged the conventional wisdom that administration could be sufficiently described from the perspective of male incumbents alone.

As the study of women in educational administration grew, so, too, did the percentage of women who achieved the position of superintendent. For example, by 1992, AASA reported approximately 7% of the nation’s superintendents were women (Glass, 1992). Even with this fourfold increase in 20 years, women remained dramatically underrepresented. For women to be proportionally represented, 80% of school superintendents should have been superintendents, given that women were 80% of teachers, the pool from which administrative aspirants emerge. The Census Bureau identified the superintendency as the most male-dominated executive position of any profession in the United States (Glass, 1992). Additional research highlighted the school superintendency as the most gender-stratified (that is, segregated) occupation in the United States (Björk, 1999; Skrla, 2000).

Further studies conducted by the American Association of School Superintendents found that in 2000, 13.2% of superintendents were women (Glass et al., 2000), and by 2003, 18.2% of superintendents were women (Grogan and Brunner, 2005). The AASA 2010 Decennial Study found that 24.1% of existing superintendents at the time were women (Kowalski et al., 2011). For the 2015 Mid-Decade Study, 27% of respondents were women. Unfortunately, since the data did not document the extent to which the 2015 survey respondents were representative of the population, we cannot be sure that the 27% finding is accurate.

While, at a little more than one-fourth, there is a continuing dearth of women in the superintendency and the percentage of minority women is dismal. Alston (2005) emphasized, “[i]n these United States, persons of color represent 10.9% of the nation’s teachers, 12.3% of the nation’s principals, but only 2.2% of the nation’s superintendents” (p. 675). For almost as long as there has been research focused on women in educational administration and the pursuit of the superintendency, there has been parallel research highlighting the challenges for aspiring and sitting superintendents of color (Arnez, 1982; Ortiz, 1982; Chase, 1995; Enomoto et al., 2000). There also has been research focused on Hispanic/Latina superintendents, specifically by Méndez-Morse (1997, 1999, 2000), Ortiz (1999, 2000), Manuel and Slate (2003), Quilantán and Menchaca-Ochoa (2004), and Couch (2007).

There is now more attention on the intersection of race and gender, which highlights the underrepresentation of and challenges for female African-American superintendents (Revere, 1985; Alston, 1999, 2000, 2005; Brunner and Peyton-Caire, 2000; Tillman and Cochran, 2000; Simmons, 2005; Brown, 2014). Alston (2000) found that while, overall, women have moved into powerful positions in a variety of professions, including education, African-American women are still a minority. According to Brown (2014), research is needed that specifically targets the needs of African-American women as they have experienced the dual discrimination of being both African-American and women because:

The voices of many African American women superintendents have been assigned to the voices of White women and African American men. Rarely are the voices of African American women superintendents revealed to solely address the issues and challenges of recruitment and retention faced by African American women to the public school superintendency. Neither, has credence or validation been given to the impact of race, gender, and social politics on the recruitment and retention process of African American women in the public school superintendency (p. 576).

Unfortunately, despite the noted lack of women, and, in particular, minority women in the superintendency, the AASA 2015 Mid-Decade Study is not able to provide a current snapshot of race and gender in the position in the United States. The overall response rate was low, and in addition, lacked tests of possible bias by non-responders. Due to this, the representativeness of the population of superintendents based on the respondents is unclear. Table 1 reports respondents by race and gender of those who responded to the survey.

A number of studies highlight the fact that women enter the superintendency later than their male counterparts because they spend more time in the classroom and in intermediate positions (Ortiz, 1982; Heilbrun, 1988; Shakeshaft, 1989; Gupton, 1998; Glass, 2000; Tallerico and Blount, 2004; Björk and Kowalski, 2005; Grogan and Brunner, 2005; Mahitivanichcha and Rorrer, 2006; Kowalski et al., 2011). For respondents to the 2015 Mid-Decade Survey, 69.3% were 51 or older (the median age for white women was 55 years, while for women of color, the median age was 51 years). The average age that women first became a superintendent is 47.1 years of age with an average total of 6.9 years in the superintendency. Among women, there were no differences by race in the number of years in the superintendency or their age when they became a superintendent. Men are statistically significantly1 more likely to become a superintendent at a younger age than women (43 versus 47 years of age) and are also more likely to have been in the superintendency longer than women (10 versus 7 years). However, there is no difference between males and females in the time spent in their current superintendency at the time of the Mid-Decade Survey (5.7 years), challenging the notion that women have shorter tenure in the position.

According to the 2015 Mid-Decade Study, women are still more likely than men to be hired as superintendent from the district in which they work (54.3 versus 41.7%), which may indicate that school boards are more willing to take a chance on an unknown male candidate than an unknown female candidate. Or, it might indicate that women are more qualified than the men in their districts for the superintendency. Among Mid-Decade respondents who were looking for a superintendency, 81% of women and 75% of men were hired within 6 months of beginning their search. There are no longer differences between women of color and white women on any of the above variables.

For classroom teaching, the number of years men and women superintendents spent in the classroom has been significantly different until now. Women superintendents used to spend more time as classroom teachers than men (Shakeshaft, 1989). According to Glass et al. (2000), 40% of male superintendents reported spending 5 or fewer years as classroom teachers; whereas according to Brunner and Grogan (2007), 41% of female superintendents reported spending 11 or more years as classroom teachers. However, the 2015 AASA Mid-Decade Survey found that 43% of superintendents spent 11 or more years as classroom teachers. There were no statistically significant differences between females and males, with the mean number of years for females at 10.8 and the mean years for males at 9.2. There were no differences among women by race.

Career paths are impacted by gender and race (Brunner and Grogan, 2007). Vail (1999) found a difference between the genders in the ascent to the superintendency. For males, the career path was teacher, high school principal, and then superintendent. For women, it was teacher, elementary principal, central office director, and then superintendent. Edgehouse (2008) echoed Vail’s findings and said, “Although more women lead elementary buildings, men clearly dominate high school principal and superintendent positions. This could indicate an additional barrier to the superintendency in that attaining a high school principalship is rare for women, yet this position is a likely step in the career path of those who have reached the top” (p. 16). Vail characterized this as an “unofficial” route to the superintendency and stated,

…there is also an unofficial path to the superintendency, and it traditionally begins with the high school principalship. Many would-be superintendents spend time at the helm of a secondary school; after all, high school principals handle large budgets and numerous employees, which are seen as good training for a superintendent. The next step is often a central office position in the business or facilities office – again, good experience for a superintendent, who will need to manage money and construction (p. 24).

The majority of all respondents to the 2015 Mid-Decade Study follow the typical career path to the superintendency (see Table 2). However, there are several gender differences that are both statistically and practically significant.2 Gender differences are most notable at assistant principal and principal positions, which have a higher number of male superintendents with this experience and the district coordinator and central office position, which have a higher number of female superintendents with this experience.

Among women in the Mid-Decade Survey, the majority of superintendents of color, as well as white, followed the path of teacher, principal, and then central office/district administrator to the superintendency—a change in Brunner and Grogan’s (2007) findings that nearly half of women superintendents did not follow that path.

Some interesting new patterns emerged, particularly the experiences of paraprofessional, military, and non-education management that women superintendents of color are more likely to bring to the job (see Table 3). Among women, there are other differences by race. A smaller proportion of women of color have been assistant superintendents, but more have been assistant principals, a path more similar to males.

Studies by Kim and Brunner (2009), Vail (1999), and others (Shakeshaft, 1989; Grogan and Brunner, 2005; Brunner and Kim, 2010) found that men’s mobility is much more likely to be found in various line positions. Because of this, men are often provided greater visibility in their positions and, thus, experience increased job opportunities. The AASA 2015 Mid-Decade Study also found differences in the experience of males and females in assistant principal and principal positions—both line positions—and district coordinator and central office experience—both staff positions.

The 2015 Mid-Decade Survey examined a number of variables related to teaching and curriculum interest and knowledge that provide perspective. Similar to Brunner and Grogan’s (2007) findings, women superintendents (65.2%) are more likely to belong to the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development than men superintendents (46.1%). While, as noted, the number of years spent in teaching is not meaningfully different between women and men,3 women are more likely to have been a master teacher, a district coordinator, and an assistant superintendent—positions that often indicate a focus on curriculum.4

Two questions in the Mid-Decade Survey allowed us to make a comparison between why superintendents believe they were hired and what the board emphasized once they were in the position. As illustrated in Table 4, women and men have different beliefs about why they were hired and what the board expects. Women believe that more than 50% of the reason they were hired was due to administrative experiences and curriculum and instruction knowledge, while men believe that they were hired for their personal characteristics and administrative experiences. There were statistical and meaningful differences between the percentage of women and men who thought they were hired for their curriculum and instruction knowledge, with women ranking it second and men ranking it fifth. This might be evidence that women believe they are strong in curriculum and instruction and men less so. It might also believe that women think boards of education value curriculum experience. Both females and males agreed on the first three board expectations for their jobs: effective communicator, problem solver, and fiscal oversight. After these characteristics, the genders part in their perceptions, with women placing emphasis on instruction next and men reporting it as next to last in expectation and emphasis. In two areas, there were statistical and meaningful gender differences in what superintendents believed was expected: instructional leadership and statespersonship.

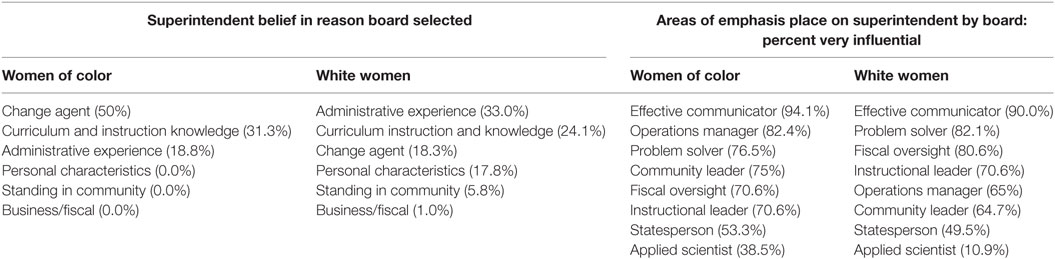

Similar to Brunner and Grogan’s (2007) findings, women superintendents of color were more likely than white women superintendents to believe they were hired as a change agent and for their curriculum skills. White women superintendents were more likely than women superintendents of color to believe they were hired for their administrative experiences, personal characteristics, standing in the community, and fiscal experience. All of the women superintendents rated their curriculum skills as the second strongest reason for being hired.

While there were differences in beliefs about emphasis placed on them by the board, both superintendents of color and white superintendents placed effective communication as the strongest emphasis. For every other emphasis, there were statistical and meaningful differences by race.

Table 5 below compares why women think they were hired and what their school boards emphasized is likely to be a combination of being hired for what the district needed and the differences in district needs. However, in many of these categories, the characteristic the superintendent believed was the strongest explanation for being hired differed from what was expected once in the superintendency, which might be the result of a change in board members (see Table 5). These differences might also be the source of discontent. For instance, while women placed their knowledge of curriculum and instruction as the second strongest reason they were hired, when we examined what is being expected of them, being an instructional leader is toward the bottom of the list, although with a high percentage still believing it is part of their job expectation.

Table 5. Why women superintendents believe they were hired versus board emphasis once in the job by race.

The responses from the AASA 2015 Mid-Decade Survey5 allow a look into size of districts (see Table 6), although there is no information on leadership in the school systems that belong to the Council of Great City Schools. While it is true that women are more likely to lead rural schools (56.8%), this is only true for white women. Similar to Brunner and Grogan’s (2007) findings, women of color tend to lead urban schools.6 Women of color are more likely than white women to be superintendents in large school districts. However, similar to white women superintendents, the majority of women superintendents of color head districts of 3,000 or fewer. Unlike the Brunner and Grogan study, there were no statistically or practically significant differences in the race of women who are superintendents in suburban schools.

It is important to note that the classification of rural does not necessarily equate with small and the classification of urban does not necessarily equate with large. When districts are examined by size, there are differences by race in the size of the district headed by a woman superintendent.

There were significant differences in the racial composition of communities and student populations by race. Women of color are more likely to lead districts of color with a school population of color than are white women superintendents.7

Overall, women are more likely than men to head school districts with a larger percentage of people of color in the community, a larger number of students who are homeless, and a larger number of students with disabilities. This might be an indication that women superintendents are hired in more challenged school districts and that men work in school districts with less adversity.

The 2015 Mid-Decade Survey also provides information on education preparation and mobility. More than half (60.5%) of all women superintendents have a doctorate or another professional degree (i.e., law, master of business administration). This is a statistically significantly higher percentage than male superintendents. Both female superintendents of color and white female superintendents are more likely to have a doctorate/professional degree than male superintendents (see Table 7).

While women are more mobile than commonly believed, the 2015 Mid-Decade Survey reveals that neither women nor men are highly mobile: 98% of women superintendents and 95% of male superintendents have worked in some capacity in two or fewer districts.

In earlier research conducted on women in educational leadership, Shakeshaft (1987) identified that barriers to women’s advancement could be labeled as either internal or external. Internal barriers that kept women out of key educational leadership positions included “low self-image, lack of confidence, and lack of motivation or aspiration” (Shakeshaft, 1987, p. 83). Though Shakeshaft (1979) found these claims were not backed by convincing data, they were reported by other studies conducted in the 1970s and 1980s that suggested that women were often their own worst enemies in keeping them from administrative positions (Dias, 1975; Gross and Trask, 1976; Sample, 1976). As the study of women in administration grew, the focus on internal barriers shifted. A number of later studies found that the gender-specific attitudinal behaviors that were previously identified tended not to prove true for women (Gupton and Slick, 1996; Brown and Irby, 1998; Grogan and Brunner, 2005).

While the AASA 2015 Mid-Decade Study did not examine family concerns as a barrier to women in the superintendency, it does report information on relationship status and children. As displayed in Table 8, male superintendents (94.2%) are more likely to be in a relationship, primarily marriage, than women superintendents (81.3%). The differences by race for women superintendents are not significant.

Parenthood experiences are starkly different between men and women as well. Table 9 shows the differences by number of children. White female superintendents are the least likely group to have children, followed by female superintendents of color. Both groups are nearly three to four times more likely to be childless than are males.

It has sometimes been assumed that women are not mobile and that partners limit women’s choice of jobs. The AASA 2015 Mid-Decade data reveal that 56% of single and 36% of married/partnered women have changed superintendencies. Among married women superintendents, nearly 26% report that their spouse or partner has moved and 18% report that their spouse has changed jobs to support them in new superintendencies. For 20% of married women superintendents, spouses have reduced hours on the job to accommodate their partner’s superintendency and 10% have left the workplace.

The 2015 Mid-Decade response to a question about whether the superintendent experienced stress in the superintendency found no gender differences, with 66.8% of superintendents reporting stress in the job. Similar to Grogan and Brunner’s (2005) findings, the Mid-Decade Study asked respondents several types of questions that might indicate the presence of stress. One group of questions asked respondents to rate assets and liabilities; another set asked about job stress; a number of questions inquired about experiencing incidents that might cause stress; and yet another group of questions focused on relationships with the school board, employees, and the community. However, when superintendents were asked why they left their previous job, of those who had moved, 5.3% of women versus 0% of men reported that they left because of health and stress. This finding deserves further exploration to determine what about the job is more likely to affect women’s health than it is to affect men’s well-being.

A cluster of questions asked respondents if they had experienced specific challenges in their position. Table 10 displays the percent of superintendents who have faced these challenges. If there are no differences by gender or race, the percentages are in the “All” category. If there are differences, the percentages are under the appropriate column heading.

As can be seen in Table 10, the majority of the challenges that superintendents face are similar, with few differences by gender or race within gender. Females find job stress more of a challenge than local and state funding, while, for males, local and state funding is the leading job stress. Similarly, males are more likely than females to be challenged by intrusion of federal regulations, and white females more likely than females of color to find this a problem. It is unclear why this is the case, assuming that federal regulations are equally distributed. Perhaps women are more likely to welcome federal regulations and the pressure for equity than are men.

More than twice the percentage of women of color than white women finds role conflict a challenge. One speculation about why this might be true is that women of color are more likely than white women to be asked to represent their both their race and their communities while still being required to serve as a “neutral” figure.

Not surprisingly, females are more likely than males to still find the “Old Boy” (“Old Girl”?) network a problem, making it their sixth most challenging aspect. Combining this with job stress and excessive time requirements corresponds to previous research that find women are expected to spend more time at work and to be more involved than are men (Grogan, 1996; Kochan et al., 1999).

The AASA 2015 Mid-Decade Survey asked questions about superintendents’ relationships with school boards. Most female superintendents (83.5%) consider their school board an asset, 74.9% believe that they exert very much influence on their school board and another 23.7% believe that they exert some influence on their school board. Women superintendents are largely satisfied with their school boards, with 82.7% reporting they are very or somewhat satisfied. Women superintendents are much influenced by their school boards (64.9%) or somewhat influenced by their school board (32.7%). When asked if their relationship with the school board inhibited their effectiveness as a superintendent, 77% said no, but 23% thought it did. There are no gender differences in any of these findings. There are differences by race among women superintendents on influence. Female superintendents of color are much less likely to believe that they have influence on the school board than are white female superintendents. The larger the percentage of women on the school board, the more women superintendents report satisfaction with their career choice and current district.

As mentioned above, superintendents reflected on the reasons why they were hired (see Table 11). Following earlier trends in the research, female superintendents believe that they were favored for their curriculum and instructional leadership more than did males. Males are more likely to believe that they were selected for their personal characteristics more than did females. Both believe that they were hired for their administrative experience.

An additional challenge for female superintendents has been the lack of mentors, both while they aspire to the superintendency as well as once they achieve the position (Radich, 1992; Grogan, 1996; Beekley, 1999; Sherman et al., 2008). Brunner and Grogan (2007) posit that one reason why so few women have achieved the job of superintendent is due to a lack of support and mentorship for women aspiring to the position. Nearly 94% of women in the Mid-Decade Study indicated that they had been mentored.

The Mid-Decade Study supports a decrease in mentoring, with nearly 72% of women reporting that they have served as a mentor to another superintendent or aspiring superintendent. In Succeeding as a Female Superintendent, Gilmour and Kinsella (2009) asserted that mentors play a crucial role in developing the skills of a superintendent, no matter the years of experience in the position.

Female superintendents talk about the “voices of inspiration” their mentors provided when asked about a mentor–mentee relationship. Under critical reflection, however, it often appears that many of these women had not actually received true mentorship and that the relationship was, in fact, passive (Sherman et al., 2008; Newcomb, 2014).

Mentoring by race and gender was explored in the AASA 2015 Mid-Decade Survey (see Table 12). White females are the most mentored group, followed by white males, then females of color and finally males of color. Nearly three quarters of white females, white males, and males of color report mentoring. About half of females of color report mentoring another superintendent. Table 12 indicates that we are most likely to mentor those like ourselves:

• White women mentor white women more than other groups.

• White males mentor white males more than other groups.

• Females of color mentor females of color more than other groups.

• Males of color mentor males of color more than other groups.

Understanding the reasons why women superintendents leave a position has been the focus of a handful of researchers. Robinson (2013) studied why women leave the superintendency. In her interviews of 20 women, she found that women left for a variety of reasons. Some were positive—like moving to a larger district or more prestigious position—but more were for reasons that found these women leaving the position altogether. These reasons included (1) the position being different than anticipated; (2) the challenge of competing politics (school boards, boards of supervisors/city councils); (3) the desire to reclaim family cohesiveness; (4) health challenges; and (5) lack of “fit” with the employing district. Some questions in the 2015 Mid-Term Survey identified possible reasons why superintendents left their previous position. Fewer than half (48%) had been in a superintendency prior to the one they were currently in. Of those who had a previous superintendency, here were some gender differences, but among women, there were no race differences. Males were more likely than females to have left their previous jobs to (1) assume a new challenge, (2) increase their compensation, and (3) move to a better community environment. Females were more likely than males to have left for health reasons, have been dismissed, or left because of conflict with community groups. For both men and women, the moving to assume a new challenge was at the top of the list (see Table 13).

When looking at the role of the female superintendent in relation to her male counterpart, it is often highlighted in the research that women lead in the superintendency differently than men. It is perceived that good superintendents not only manage the district well but also prioritize child and family well-being and student learning.

Research has suggested that female educational leaders tend to be child centered in leading their systems and, because of their varied and extensive background in curriculum and instruction, they are believed to emphasize effective learning climates (Fansher and Buxton, 1984; Andrews and Basom, 1990; Dillard, 1995; Grogan, 1996). There is a strong desire to make schools better places for children (Beekley, 1999; Shakeshaft et al., 2007; Grogan, 2008; Grogan and Shakeshaft, 2011). Ever since AASA has been disaggregating their surveys by gender, the ability to be an instructional leader has always been identified by women as the primary reason they were selected for the position, answered by 37% of female respondents in 2000 (Glass et al., 2000) and 33% in 2010 (Kowalski et al., 2011). In fact, in the 2010 study, women were twice as likely as men to identify being an instructional leader as the primary reason for their selection as superintendent (Kowalski et al., 2011). In the Mid-Decade Study, 23% of women reported that they were hired because of their curriculum and instruction knowledge as opposed to 6% of men, nearly four times as likely as men to see this as their asset.

Given their lengthy backgrounds climbing the ladder to the superintendency, it comes as little surprise just how invested in curriculum and instruction most female superintendents tend to be. The frustration in some cases for women is when they are denied the opportunity to participate in the instructional decisions of the district (Grogan, 2008). In another study, a number of women chose to leave the position of superintendent because they were not able to focus as much on instruction as they had assumed the position would allow (Robinson, 2015). In the Mid-Decade Study, 71% of women said that instructional leadership was strongly emphasized by their boards. However, there were three other roles that the board emphasized as more important than instructional leadership: effective communicator, problem solver, and fiscal oversight.

Research has emerged that shows that women’s leadership styles are often more collaborative and facilitative than male leaders. They are interested in moving the best idea forward, not necessarily their personal idea forward (Hill and Ragland, 1995; Regan and Brooks, 1995; Grogan, 1996; Gupton and Slick, 1996; Marshall et al., 1996; Brunner, 1997; Grogan and Smith, 1998). Because of their interest in building capacity through relationships and teamwork, women leaders often regularly solicit input from parents and community members.

Although the AASA 2015 Mid-Decade Survey did not pose many questions that speak to the relational aspect of women’s leadership, there are a number of issues that women identify as important to their leadership and success. For instance, two thirds or more of women superintendents rank working with their staff and communities as an asset to them. Women value working with others, both internally and externally (Table 14), and they are more likely than men to report that other groups are strong influences or assets to their leadership. These are the characteristics of leaders who value collaboration (Table 14).

Women are more likely than are men to report strong influence on their decisions of other administrators in their district, teachers, unions, community special interest groups, elected local officials, AASA, and state superintendent associations (Table 15).

Although not necessarily a sign of collaboration, the more political action groups in a district might signal lack of collaboration that has moved people to organize. A larger percentage of male superintendents than female superintendents report more political action among groups in their districts on several issues: funding, student testing, bullying, and safety. The level of political action on issues is demonstrated in Table 16. These differences might indicate superintendent leadership, or lack of leadership, on these issues and community engagement, arguing that the more political action that is necessary by the community, the less likely the superintendent is to be leading coalitions.

Women rate themselves fairly highly on the effectiveness of their leadership and, on all but one item, their ratings are statistically significantly higher than those of males (see Table 17).

The AASA 2015 Mid-Decade Survey confirms many of the trends we have seen in the research over the past 15 years. The profiles of women superintendents are becoming more like their male counterparts. For instance, both men and women appear to be less mobile than in the past. Men and women are spending about the same time as teachers before becoming superintendents, women and men appear to experience stress similarly in the superintendency, and women are receiving necessary mentoring much more than in the past. There is also no difference in the number of years women and men have served in their current superintendency. There are few data to support the beliefs that women superintendents are limited by family circumstances although this survey sheds no light on perspectives of women aspirants. This survey also confirms that there are a variety of paths to the position providing opportunities for women who have not necessarily had the typical teacher/principal/central office administrator trajectory. Nevertheless, significant differences do still exist between men and women’s beliefs of why they were hired: women superintendents are still more likely to bring expertise in curriculum and instruction than men. In addition, white women are still more likely to be hired in smaller districts than white men. Perhaps most revealing, this survey confirms that women of color are more likely than white women to lead majority–minority districts although, in general, women are more likely than men to lead districts with a larger percentage of people of color in the district. All women are more likely to head a district with a larger number of students who are homeless and a larger number of students with disabilities, than men. These are important new findings and suggest some perhaps useful speculation.

• Do personal characteristics matter? Women superintendents are less likely to have children of their own than are male superintendents. Interestingly, both groups find the job stressful. Women are more likely to be promoted from within than men. Does that mean that, compared to men, they are more patient? More dedicated to their current responsibilities? Less ambitious? And, women are now more willing to rate themselves highly as leaders than are men.

• There is an interesting coincidence between the growth of scholarship and advocacy about the accession of women to the superintendency and that accession in practice and fact.

• It is worth speculating about what accounts for the growth in the proportion of superintendents who are women. Is it because their skills sets are more aligned with the teaching/learning improvement needs of schools? Is it because they both “manage” the district and attend to children, youth, and families? Is it because boards (and female board members) have advocated for them? Is it a function of social justice? Is it because the first generations of women superintendents have lit a path now being followed by others? Is it because the job has become harder and less prestigious and fewer capable men are interested in the position? Or is it all of the above?

• The growing proportion of women in the superintendency traces an arc toward equality of opportunity similar to that of other previously underrepresented and underserved groups, for example, children with special needs, children whose language of origin is not English, children from low-income families, and indeed, children from non-Caucasian families.

AASA’s Mid-Decade Study is a contribution to a continuing issue. However, concerns still remain. Above all, women are still acutely underrepresented in the superintendency and women of color are extremely rare. Unfortunately, this latest survey, like so many in the past, relied on a representative sample of the population of superintendents nationwide; thus, we do not know the exact proportion of men and women superintendents in the United States. The only comprehensive survey of the entire population of women superintendents was conducted by Cryss Brunner and Margaret Grogan several years ago (Brunner et al., 2003; Grogan and Brunner, 2005; Brunner and Grogan, 2007). We believe that it is time for a concerted effort to be made to ascertain current information. When researchers can do nothing other than offer reasonable estimates of the lack of representation, the problem is not taken seriously. In addition, most of the research in the past 30 years has found great variation in the lived experiences of women and men in the superintendency, shaped significantly by race, ethnicity, gender identification, support systems, and district contextual factors. Survey data, such as those collected for the AASA 2015 Mid-Decade Survey, are most meaningful when followed up by in-depth interviews. We recommend that researchers probe these findings for the nuances that will better inform women and other underrepresented aspirants to the superintendency—so that the most important leadership position in US education will be equally well represented across all sectors of our diverse society.

KR was the primary writer of the manuscript. CS analyzed the data and wrote sections. MG and WN each wrote a section of the article.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Alston, J. A. (1999). “Climbing hills and mountains: black females making it to the superintendency,” in Sacred Dreams: Women and the Superintendency, ed. C. C. Brunner (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press), 79–90.

Alston, J. A. (2000). Missing from action: where are the black female school superintendents. Urban Educ. 35, 525–531. doi: 10.1177/0042085900355003

Alston, J. A. (2005). Tempered radicals and servant leaders: black females persevering in the superintendency. Educ. Adm. Q. 41, 675–688. doi:10.1177/0013161X04274275

Andrews, R. L., and Basom, M. R. (1990). Instructional leadership: are women principals better? Principal 70, 38–40.

Arnez, N. I. (1982). Selected black female superintendents of public school systems. J. Negro Educ. 51, 309–317. doi:10.2307/2294698

Beekley, C. (1999). “Dancing in red shoes: why women leave the superintendency,” in Sacred Dreams: Women and the Superintendency, ed. C. C. Brunner (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press), 161–175.

Bell, C. (1988). Organizational influences on women’s experience in the superintendency. Peabody J. Educ. 65, 31–59. doi:10.1080/01619568809538620

Biklen, S., and Shakeshaft, C. (1985). “The new scholarship of women,” in Handbook for Achieving Sex Equity through Education, ed. S. Klein (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press), 44–52.

Biklen, S. K., and Brannigan, M. (eds) (1980). Women and Educational Leadership. Lexington, MA: D. C. Heath and Company.

Björk, L. (1999). Collaborative research on the superintendency. AERA Res. Superintendency SIG Bull. 2, 1–4.

Björk, L., and Kowalski, T. (2005). The Contemporary Superintendent: Preparation, Practice, and Development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Björk, L. G. (2000). Introduction: women in the superintendency – advances in research and theory. Educ. Adm. Q. 36, 5–17. doi:10.1177/00131610021968877

Blount, J. M. (1998). Destined to Rule the Schools: Women and the Superintendency. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1873–1995.

Brown, A. R. (2014). The recruitment and retention of African American women as public school superintendents. J. Black Stud. 45, 573–593. doi:10.1177/0021934714542157

Brown, G., and Irby, B. J. (1998). “Getting the first school executive position,” in Women Leaders: Structuring Success, eds B. J. Irby and G. Brown (Dubuque, IA: Kendall Hunt), 98–111.

Brunner, C. C. (1997). Working through the riddle of the heart: perspectives of women superintendents. J. Sch. Leadersh. 7, 138–164.

Brunner, C. C., and Grogan, M. (2007). Women Leading School Systems: Uncommon Roads to Fulfillment. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Brunner, C. C., Grogan, M., and Prince, C. (2003). AASA national survey of women in the superintendency and central office: preliminary results. Paper Presented at the Annual Conference of the American Educational Research Association, Chicago, IL.

Brunner, C. C., and Kim, Y. (2010). Are women prepared to be superintendents? Myths and misunderstandings. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 5, 276–309. doi:10.1177/194277511000500801

Brunner, C. C., and Peyton-Caire, L. (2000). Seeking representation: supporting black female graduates students who aspire to the superintendency. Urban Educ. 35, 532–548. doi:10.1177/0042085900355004

Chase, S. E. (1995). Ambiguous Empowerment: The Work Narratives of Women School Superintendents. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press.

Couch, K. (2007). The Underrepresentation of Latinas in the Superintendency: A Comparative Case Study of the Perceptions and Lived Experiences of Latina Superintendents and Aspirants in the Southwest. Doctoral dissertation. Available from ProQuest dissertations and theses database (UMI No. 3296151).

Cunningham, L. L., and Hentges, J. T. (1982). The American School Superintendent 1982: A Summary Report. Arlington, VA: American Association of School Administrators.

Dias, S. L. (1975). A Study of Personal, Perceptual and Motivational Factors Influential in Predicting the Aspiration Level of Women and Men toward the Administrative Roles in Education. Unpublished Doctoral dissertation, Boston University, Boston, MA.

Dillard, C. B. (1995). Leading with her life: an African American feminist (re)interpretation of leadership for an urban high school principal. Educ. Adm. Q. 31, 539–563. doi:10.1177/0013161X9503100403

Edgehouse, M. A. (2008). Characteristics and Career Path Barriers of Women Superintendents in Ohio. Unpublished Doctoral dissertation, Bowling Green State University, Bowling Green, OH.

Edson, S. K. (1988). Pushing the Limits: The Female Administrative Aspirant. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Enomoto, M., Gardiner, E., and Grogan, M. (2000). Notes to athene: mentoring relationships for women of color. Urban Educ. 35, 567–583. doi:10.1177/0042085900355007

Fansher, T., and Buxton, T. (1984). A job satisfaction profile of the female secondary school principal in the United States. Nat. Assoc. Second. Sch. Princ. Bull. 68, 32–39.

Gilmour, S. L., and Kinsella, M. P. (2009). Succeeding as a Female Superintendent: How to Get There and Stay There. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Glass, T. E. (1992). The 1992 Study of the American School Superintendency: America’s Education Leaders in a Time of Reform. Arlington, VA: American Association of School Administrators.

Glass, T. E., Björk, L. G., and Brunner, C. C. (2000). The 2000 Study of the American School Superintendency: A Look at the Superintendent of Education in the New Millennium. Arlington, VA: American Association of School Administrators.

Grieder, C., Pierce, T. M., and Jordan, K. F. (1969). Public School Administration, 3rd Edn. New York: Ronald Press.

Grogan, M. (1996). Voices of Women Aspiring to the Superintendency. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Grogan, M. (1999). Equity/equality issues of gender, race, and class. Educ. Adm. Q. 35, 518–536. doi:10.1177/00131619921968743

Grogan, M. (2008). The short tenure of a woman superintendent: a clash of gender and politics. J. Sch. Leadersh. 18, 634–660.

Grogan, M., and Brunner, C. C. (2005). Women leading systems: latest facts and figures on women and the superintendency. Sch. Adm. 62, 46–50.

Grogan, M., and Shakeshaft, C. (2011). Women and Educational Leadership. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Grogan, M., and Smith, F. (1998). A feminist perspective of women superintendents’ approaches to moral dilemmas. Just Caring Educ. 4, 176–192.

Gross, N., and Trask, A. E. (1976). The Sex Factor and the Management of Schools. New York: John Wiley.

Gupton, S. (1998). “Who’s to take care of the children?” in Women as School Executives: The Complete Picture, eds A. Pankake, G. Schroth, and C. Funk (Austin, TX: Texas Council of Women School Executives), 207–212.

Gupton, S. L., and Slick, G. A. (1996). Highly Successful Women Administrators: The Inside Story of How They Got There. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Hansot, E., and Tyack, D. (1981). The Dream Deferred: A Golden Age for Women Administrators. Policy Paper No. 81-C2, Stanford University School of Education, Institute for Research on Educational Finance and Governance.

Hill, M. S., and Ragland, J. C. (1995). Women as Educational Leaders. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Kim, Y., and Brunner, C. C. (2009). School administrators’ career mobility to the superintendency: gender differences in career development. J. Educ. Adm. 47, 75–107. doi:10.1108/09578230910928098

Knezevich, S. J. (1971). The American School Superintendent: An AASA Research Study. Washington, DC: American Association of School Administrators.

Kochan, F. K., Spencer, W. A., and Matthews, J. (1999). The changing face of the principalship in Alabama: role, perceptions, and gender. Paper Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Montreal, QC.

Kowalski, T. J. (2005). The School Superintendent: Theory, Practice, and Cases. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Kowalski, T. J., McCord, R. S., Petersen, G. J., Young, I. P., and Ellerson, N. M. (2011). The American School Superintendent: 2010 Decennial Study. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Mahitivanichcha, K., and Rorrer, A. K. (2006). Women’s choices within market constraints: re-visioning access to and participation in the superintendency. Educ. Adm. Q. 42, 483–517. doi:10.1177/0013161X06289962

Manuel, M., and Slate, J. R. (2003). Hispanic female superintendents in America: a profile. Adv. Women Leadersh. J. Available at: http://awljournal.org/winter2003/MANUEL~1.html

Marshall, C. (1984). University educational administration programs and sex equity. AASA Professor 17, 6–12.

Marshall, C. (1985). From culturally defined to self-defined: career stages of women administrators. J. Educ. Thought 19, 134–147.

Marshall, C., Patterson, J. A., Rogers, D. L., and Steele, J. R. (1996). Caring as career: an alternative perspective for educational administration. Educ. Adm. Q. 32, 271–294. doi:10.1177/0013161X96032002005

Méndez-Morse, S. E. (1997). The Meaning of Becoming a Superintendent: A Phenomenological Study of Mexican American Female Superintendents. Doctoral dissertation, Retrieved from ProQuest dissertations and Full theses, UMI No. 9825026.

Méndez-Morse, S. E. (1999). “Redefinition of self: Mexican-American women becoming superintendents,” in Sacred Dreams: Women and the Superintendency, ed. C. C. Brunner (Albany: State University of New York Press), 125–140.

Méndez-Morse, S. E. (2000). Claiming forgotten leadership. Urban Educ. 35, 584–596. doi:10.1177/0042085900355008

Newcomb, W. S. (2014). “A bricolage of voices: lessons learned from feminist analyses in educational leadership,” in The International Handbook on Social [in]Justice and Educational Leadership, eds I. Bogotch and C. Shields (New York: Springer), 199–216.

Ortiz, F. (1982). Career Patterns in Education: Women, Men and Minorities in Public School Administration. New York: Praeger.

Ortiz, F. I. (1999). “Seeking and selecting Hispanic female superintendents,” in Sacred Dreams: Women and the Superintendency, ed. C. C. Brunner (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press), 91–101.

Ortiz, F. I. (2000). Who controls succession in the superintendency? A minority perspective. Urban Educ. 35, 557–566. doi:10.1177/0042085900355006

Quilantán, M. C., and Menchaca-Ochoa, V. (2004). The superintendency becomes a reality for Hispanic women. Kappa Delta Pi Rec. 40, 124–127. doi:10.1080/00228958.2004.10516421

Radich, P. A. (1992). Access and Entry to the Public School Superintendency in the State of Washington: A Comparison between Men and Women. Unpublished Doctoral dissertation, Washington State University, Pullman, WA.

Regan, H. B., and Brooks, G. H. (1995). Out of Women’s Experience: Creating Relational Leadership. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Revere, A. B. (1985). A Description of Black Female Superintendents. Unpublished Doctoral dissertation, Miami University, Miami, OH.

Robinson, K. (2013). The Career Path of the Female Superintendent: Why She Leaves. Doctoral dissertation, Retrieved from ProQuest dissertations and Full theses, UMI No. 3560514.

Robinson, K. (2015). “Why do women leave the superintendency?” in Women Leading Education Across the Continents: Overcoming the Barriers, eds E. C. Reilly and Q. J. Bauer (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield), 55–62.

Sample, D. E. (1976). Some Factors Affecting the Flow of Women Administrators in Public School Education. Unpublished Doctoral dissertation, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

Schmuck, P. A. (1976). Sex Differentiation in Public School Administration. Arlington, VA: National Council of Administrative Women in Education.

Schmuck, P. A. (1980). “Differentiation by sex in educational professions,” in Sex Equity in Education, eds J. Stockard, P. Schmuck, K. Kempner, P. Williams, S. Edson, and M. Smith (New York: Academic Press), 79–95.

Shakeshaft, C. (1989). The gender gap in research in educational administration. Educ. Adm. Q. 25, 324–337. doi:10.1177/0013161X89025004002

Shakeshaft, C., Brown, G., Irby, B., Grogan, M., and Ballenger, J. (2007). “Increasing gender equity in educational leadership,” in Handbook of Gender Equity, ed. S. Klein (Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates), 103–130.

Shakeshaft, C., Gilligan, A., and Pierce, D. (1984). Preparing women school administrators. Phi Delta Kappan 66, 67–68.

Shakeshaft, C. S. (1979). Dissertation Research on Women in Educational Administration: A Synthesis of Findings and Paradigm for Future Research. Unpublished Doctoral dissertation, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX.

Sherman, W. H., Muñoz, A. J., and Pankake, A. (2008). The great divide: women’s experiences with mentoring. J. Women Educ. Leadersh. Available at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/jwel/25

Simmons, J. M. (2005). “Superintendents of color: perspectives on racial and ethnic diversity and implications for professional preparation and practice,” in The Contemporary Superintendent: Preparation, Practice, and Development, eds L. G. Björk and T. J. Kowalski (Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press), 251–281.

Skrla, L. (1999). Masculinity/femininity: hegemonic normalizations in the public school superintendency. Paper Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Montreal, QC.

Skrla, L. (2000). The social constructional of gender in the superintendency. J. Educ. Policy 15, 293–316. doi:10.1080/02680930050030446

Skrla, L., Reyes, P., and Scheurich, J. J. (2000). Sexism, silence, and solutions: women superintendents speak up and speak out. Educ. Adm. Q. 36, 44–75. doi:10.1177/00131610021968895

Tallerico, M., and Blount, J. (2004). Women and the superintendency: insights from theory and history. Educ. Adm. Q. 40, 633–662. doi:10.1177/0013161X04268837

Tillman, B. A., and Cochran, L. L. (2000). Desegregating urban school administration: a pursuit of equity for black women superintendents. Educ. Urban Soc. 33, 44–59. doi:10.1177/0013124500331005

Tyack, D., and Hansot, E. (1982). Managers of Virtue: Public School Leadership in America, 1820-1980. New York: Basic Books.

Keywords: leadership, gender, superintendent, principal, career path

Citation: Robinson K, Shakeshaft C, Grogan M and Newcomb WS (2017) Necessary but Not Sufficient: The Continuing Inequality between Men and Women in Educational Leadership, Findings from the American Association of School Administrators Mid-Decade Survey. Front. Educ. 2:12. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2017.00012

Received: 10 January 2017; Accepted: 29 March 2017;

Published: 21 April 2017

Edited by:

Claudia Fahrenwald, University of Education Upper Austria, AustriaReviewed by:

Sui Chu Esther HO, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong KongCopyright: © 2017 Robinson, Shakeshaft, Grogan and Newcomb. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kerry Robinson, krobin44@utk.edu;

Charol Shakeshaft, cshakeshaft@vcu.edu

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.