Intercultural Comfort through Social Practices: Exploring Conditions for Cultural Learning

- 1Non-Profit Studies, University of Washington Tacoma, Tacoma, WA, United States

- 2Weatherhead School of Management, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH, United States

High-quality cross-ethnic interactions contribute to college students’ development, but knowledge is scant concerning campus settings and conditions that promote these interactions. This study indicates that distinct social practices in particular settings create such conditions. Phenomenological analysis of current and past members of a voluntary community service association (a pseudonym), appropriated to meet their social needs, revealed practices leading students from differing ethnic backgrounds to challenge stereotypes and engage in cultural learning. Inductively derived findings led to a transdisciplinary analysis that synthesizes concepts from institutional (higher education), organizational (voluntary service organization), interpersonal (social ties), and individual (personal development) levels. The emergent concept of intercultural comfort differentiated between meaningful diversity interactions within the student association and apprehensive ones elsewhere. Members experienced this intercultural comfort and an ethnically inclusive moral order due to mission-driven practices emphasizing shared purpose, fellowship, and structured interactions.

In many parts of societies where ethnic diversity is increasing, individuals from different cultural backgrounds coexist in a civil fashion and interact without expressed conflict. However, achieving the economic and social benefits of multicultural society requires more—a deep diversity (Harrison et al., 1998) characterized by intercultural learning and the skills for capitalizing on cultural differences. The benefits of diversity can be seen as residing in the building of bridging and bonding social capital, which provides trust and reciprocity to accomplish both collective and individual benefits. However, diversity in contemporary communities is found to inhibit rather than promote solidarity and social capital (Putnam, 2007). Research indicates a fundamental reason—intercultural interactions produce psychological discomfort for individuals, a discomfort that can lead to avoidance and rejection of other cultures unless a variety of conditions are met (Crisp and Turner, 2011).

Administrators at many universities have pursued particular strategies to promote diversity and diversity’s developmental benefits for students, but capturing the potential of informal settings has lagged. In addition to needed recruitment and selection efforts that increase numerical diversity, institutional policies have focused on formal educational activities, such as awareness training and multiculturalism classes. These strategies, on their own, appear to be inadequate (Moss-Racusin et al., 2014), likely reinforcing regulation and competitive perspective among some of the majority group members, as evidenced by continuing incidents reported in public media signaling persistent tensions on campus. One explanation for these inadequacies is that perceptions of intergroup competition, such as the use of organizational policies for increasing numerical diversity in admissions, are associated with negative stereotyping of minorities by majority group members (Schmader et al., 2001). The very success of representational efforts, then, can lead to limited or even negative effects on meaningful interaction in other formal diversity efforts undertaken by institutions. Given these limitations of formal actions, this research investigates informal settings that offer the promise of additional paths forward, paths aimed at producing more, and more meaningful diversity interactions among students.

Many organizations, including institutions of higher education, are making strides toward increasing diversity in their members, employees, clients, etc. However, there remains a gap between having diversity and achieving meaningful, deep-level inclusion, where individuals increase interethnic and cross-cultural learning and reduce stereotypes and biases. Based on inductively derived themes derived from student’s frank reports of their diversity interactions on campus, we propose to advance knowledge of effective practices for educational institutions by differentiating students’ superficial diversity interactions in their general campus settings from meaningful ones in a particular voluntary community service association (hereafter, VCSA).

To deepen understandings of the themes that emerged from the data, and to treat the multiple levels of relevant phenomena, the paper first discusses several bodies of relevant literature. It then presents the study’s findings on practices and norms that students reported as differentiating apprehensive from learning interactions, practices that sustained the conditions (Allport, 1954; Pettigrew et al., 2011) known to promote effective cross-racial contact. The paper continues by developing the concept of intercultural comfort as the core social feature of this differentiation, considering how comfort was produced by particular social practices in VCSA. The paper concludes by treating its identified phenomena as institutionalized, pointing toward new research directions and practical policies—ones that mate with several trends in higher education—for the broader attaining of meaningful diversity interactions.

Concepts of Intercultural Contact and Relationships

The developmental benefits of meaningful diversity interactions, coupled with the persistence of problems on campus in achieving a high frequency of positive, high-quality interactions, point to a gap in applied knowledge concerning the social determinants of meaningful, learning diversity interactions on campus. We address this gap by reviewing literature on favorable and problematic social phenomena identified in this study’s phenomenological analyses. These phenomena underlie personal development of intercultural comfort and cross-ethnic acceptance, learning and skill vs. rejection and distancing. No single theory treats the multiple phenomena, requiring several bodies of knowledge for an improved understanding.

Cross-Cultural Interactions—Benefits and Impediments

For students, and their educational institutions, the stakes regarding meaningful diversity interactions and learning are high. A substantial body of research indicates that positive (high quality), but not other, intercultural interactions are associated with particular aspects of student development, extending beyond prejudice reduction and cross-cultural interaction skills to those of leadership and critical thinking (Bowman, 2010; Denson and Bowman, 2013; Pascarella et al., 2014). High frequency matters, since low- and medium-frequency cross-cultural contacts have been found to lack such developmental benefits (Bowman, 2013). The types of positive, meaningful social ties may be multiple. Park and Bowman (2015) note that ties favoring development of students’ skills can be both bonding and bridging, and that weak ties may even have an advantage, their larger numbers providing students more frequent experiencing of the novelties leading to personal development. Indeed, numerical diversity on campus increases diversity interactions but not the stronger ties of intercultural friendships (Bowman and Park, 2014). Racial diversity on campus is not shaped by numerical integration alone but is dependent on the social forces that impact the quality and frequency of cross-cultural interactions that achieve such benefits as reduced intergroup bias, increased intellectual self-confidence, and higher degree aspirations (Bowman and Park, 2015).

If individuals and societies are to benefit from diversity, universities and other institutions should play a role in helping their members develop capabilities for interacting effectively with differing others. Recent studies suggest new strategies for creating enriching intercultural interactions and cultural learning opportunities on campus, pointing to informal multicultural interactions with diverse peers as positively influencing student development and learning (Hurtado, 2005; Milem et al., 2005; Pettigrew and Tropp, 2006; Pike et al., 2007; Denson and Chang, 2009; Bowman and Denson, 2011). The enriching interactions that result are argued to be the most beneficial college activity in which students participate, with students developing leadership skills, cultural knowledge, and social self-confidence (Antonio, 2001). These findings indicate that students’ intercultural learning and personal development are enabled by opportunities for intercultural interactions that are informal, positive, and meaningful. Particular informal settings have shown promise in overcoming distancing forces between differing groups, including cross-ethnic living arrangements (Shook and Fazio, 2008; Stearns et al., 2009; McCabe, 2011) and co-curricular activities (Cheng and Zhao, 2006), while others, such as participation in religious organizations (Park and Bowman, 2015) or ethnic/cultural clubs (Stearns et al., 2009), have not. A plausible conclusion is that positive effects of outside-of-class activities are contingent on the social conditions (Allport, 1954) and practices found in those activities or on particular campuses. Consistent with the phenomenon of intergroup competition and stereotyping, high levels of numerical diversity are insufficient to produce effective interactions, having been found to be associated with negative impacts (Rothman et al., 2003) when there is a negative campus climate for diversity (Denson and Bowman, 2013).

On U.S. campuses with ethnically diverse populations developmentally meaningful intercultural ties have been found to be lacking, with students being co-present with dissimilar others but interacting quite superficially (Halualani, 2007). Classroom integration does not result in significantly higher proportions of intercultural friendships (Stearns et al., 2009). Part of this distancing on campus is attributable to homophily, birds of a feather flocking together (Lazarsfeld and Merton, 1954; McPherson et al., 2001; Stearns et al., 2009; Stark and Flache, 2012), with such tendencies carrying over from earlier educational experiences (Shrum et al., 1988). These tendencies are long-standing, with racial homophily being stable in the U.S. over several decades (Smith et al., 2014). Distancing is also attributable to intercultural communication apprehension (Neuliep and McCroskey, 1997), with apprehension reducing the willingness to communicate (Lin and Rancer, 2003; Kim, 2012) and hampering the reduction in uncertainty after cross-cultural interactions (Neuliep and Ryan, 1998). Relatedly, distancing can stem from norms of political correctness and propriety that add uncertainty and risk to cross-cultural interactions (Ely et al., 2006).

Conditions for Overcoming Discomfort and Rejection

At the individual and group levels, a substantial review of social psychological research by Crisp and Turner (2011) concludes that psychological discomfort created by cross-cultural interactions can lead to avoidance and rejection of other cultures, unless four conditions are experienced over time: discomfort, repeated interaction, motivation, and ability. The initial condition of discomfort involves interaction in which the individual experiences an inconsistency between the observed behavior of a particular, culturally different individual and the stereotype held of the latter’s cultural group. For this discomfort to lead to learning and respect rather than tension and retreat into one’s own culture, Crisp and Turner specify the necessity of repeated interactions where the individual is motivated and able to resolve the inconsistencies. The emphasis on repetition echoes the findings on the importance of intercultural interactions being of high frequency.

A substantial body of sociological literature indicates the importance of particular structural conditions of intercultural contact. Meta-analytic findings provide strong evidence that the optimal conditions described in Allport’s (Allport, 1954) contact hypothesis, while not essential, facilitate a decrease in prejudice and conflict and provide many additional positive outcomes of greater intergroup contact, including in-group trust, out-group knowledge, and reduced anxiety and individual threat (Pettigrew et al., 2011). According to Allport, these positive outcomes occur when different groups have the opportunity to interact in settings where members have equal status interactions, work collaboratively toward a goal that cannot be achieved independently, and have support for interracial interactions from recognized-authority figures. Students are more likely to have increased intercultural interactions if appropriate propinquity mechanisms exist (Moody, 2001; Wimmer and Lewis, 2010; Park and Bowman, 2015). For instance, consistent with contact theory, the integration opportunities of extracurricular activities result in less pronounced friendship segregation (Moody, 2001). Cross-group friendships are a particularly significant contributor to positive contact (Pettigrew, 1998; Pettigrew and Tropp, 2006). They provide optimal conditions for engaging in self-disclosure and lead to greater trust, sense of cooperation, and more positive attitudes toward the out-group (Turner et al., 2007). However, these conditions are typically not treated by current policy, and they are disfavored on campus and elsewhere not only by forces of homophily (McPherson et al., 2001) and friendship segregation (Moody, 2001) but also by phenomena of cross-cultural discomfort (Crisp and Turner, 2011) and communication avoidance (Kim, 2012). The common consequences may be superficial, guarded interactions, with students failing to develop intercultural ties and learning (Halualani, 2007).

Students are most likely to experience intercultural learning after being exposed to others’ experiences and reflecting on their individual and collective social experiences with different others (Brewer, 1996; Gaertner et al., 1996; King et al., 2013). Timing matters. The earlier that college students have positive diversity interactions, the less likely they are to have negative ones later and the more likely they are to seek various diversity experiences (Bowman, 2012).

Communities for Equal-Status, Personal Ties

Communities can be differentiated on the basis of the closeness of the social relationships within them, with many contemporary communities being characterized as having relatively distant, impersonal relationships and others as more close and personal (Brint, 2001). The former type of community reflects the finding of typical intercultural interactions on campus being superficial (Halualani, 2007), while the latter suggests the possibility of more meaningful cross-ethnic interactions. Brint (2001) discusses relevant contrasts between impersonal and personal communities, updating concepts of Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft (Tönnies, 1957). Close Gemeinschaft-like communities represent a social organizing based on personal ties and shared norms and values. Impersonal, Gesellschaft-like communities exhibit greater evidence of individual self-interest, individuals coexisting more independently of one another and with lower regard for the community’s and others’ interests compared to their own, a community with only mutual tolerance (Brint, 2001). Impersonal communities are more reflective of dissimilar ways of life, dispersed ties, infrequent interactions, larger groups, temporary arrangements, an imagined community, and regulated competition (Brint, 2001). These communities, likely to represent the general environment of larger, ethnically diverse educational institutions, offer the opportunity for bridging intercultural ties (Blau, 1977; McPherson et al., 2001) of relatively weak strength.

By contrast, interpersonally close Gemeinschaft-like communities have typically been characterized by exclusion of ethnically and culturally differing others. However, Brint (2001) defines selected close contemporary communities where members learn about and appreciate the individual personalities of fellow members. In these communities, shared moral cultures and common understanding about the practice of the group—its day-to-day interactions—provide a basis for solidarity, trust, and a sense of belonging (Etzioni, 2001) and collective identity (Tajfel and Turner, 1986; Brint, 2001; Magis, 2010). Relationships are composed of equality in knowledge, volition, power, and authority, reflecting the condition of equal status conducive to effective cross-racial contact (Allport, 1954). Strong bonds of affect, loyalty, common values, and concern for others (Brint, 2001) create a close, safe community and moral order with the power to shape members’ beliefs. The power of moral order rests on prescribing a belief structure characterized by sharedness and a capacity for action (Taylor, 2003; Vaisey, 2007). These characteristics of selected contemporary communities imply interdependence, cooperation, and coordinated action for a common goal, with the will of one person influencing that of another.

For practical action in educational settings, new knowledge is needed on whether and how these socially close, equal status communities can be created in ethnically heterogeneous rather than homogeneous settings. While initially specifying the basis of close personal communities as structural—parental descent, gender, or necessity—Tönnies (1957) later included, among others, place, fellowship, kinship, neighborhood, mind, friendship, and the broader social relationships of voluntary organizations, such as leagues, associations, and special interest groups. Particular associations are capable of forming close relationships on these bases of similarity rather than ethnic similarity, achieving a recategorization of individual identity from ethnicity to some other basis of perceived similarity (Gaertner et al., 1989; Brewer, 1996).

Appropriable Social Organizations

Meaningful social relations in close communities can be exploited for additional uses. Coleman (1988) notes that some associations become “appropriable social organizations” (p. 108), whereby a voluntary organization created for one purpose, such as community organizing, provides to members’ a social capital available for uses unrelated to that original purpose. Achieving such additional uses requires “closure of social networks” (p. 105), with members actually having relationships with each other. These purpose-driven relationships can then be appropriated by the members to serve other of their needs, such as friendship formation. While many campus associations are ethnically homogeneous, including most Greek societies (Milem et al., 2005), various types of co-curricular college contexts, ones created for purposes unrelated to ethnic similarity, present favorable conditions for close heterogeneous association. These co-curricular contexts have been found to influence the formation of interracial ties, leading to a call for further inquiry into the elements of college environments associated with interracial friendships (Moody, 2001; Chang et al., 2004; Stearns et al., 2009).

Social Practices

Despite past attention to conditions favoring positive intercultural contact, little attention has been given to identifying social practices on campus that create and sustain these conditions. An instructive exception is McCabe’s (McCabe, 2011) study of a multicultural sorority, linking the sustaining of its heterogeneity and its promotion of multiculturalism to specific practices among its members. These practices included recognizing and valuing differences, teaching and learning about differences, and bridging differences via diversity interactions and organizational alliances. Such social practices governing behavior are complex and socially embedded in routinized behavior, involving the multiple dimensions of bodily and mental activities, know-how, discourse, and emotion (Reckwitz, 2002).

Drawing on the above concepts to interpret this study’s emergent findings enables this study of students’ experiences to provide new knowledge of the following two inter-related phenomena: (1) the role of intercultural comfort in fostering sustained developmental interactions and (2) the social practices that lead to intercultural comfort. In particular, we ask, what distinguishes the practices of meaningful intercultural interactions in contexts where personal, equal-status, ethnically heterogeneous ties and learning are found from those in other campus contexts?

Research Design

In this study, we use intensive qualitative methods to analyze students’ experiences. These methods enable us to inquire into particular practices in the VCSA that overcame the impediments of homophily, cross-cultural discomfort, and communication apprehension to produce high-frequency, meaningful diversity interactions, while practices in many other campus settings did not. The study’s intended purpose was to develop practical propositions about beneficial, meaningful diversity interactions on campus, applying inductive methods using a phenomenological approach to current students’ and past graduates’ experiences as members of VCSA. Eight pilot interviews of higher education administrators from various institutions were conducted. When asked about sites of meaningful diversity interactions on campus, administrators at one university suggested investigating the study’s focal association. This co-educational voluntary student association has thousands of members performing community service in chapters on hundreds of U.S. campuses. Its formally stated purpose is to develop leadership, promote friendship, and provide service to humanity. Students in VCSA typically participated each week in an organizational meeting, community service, and a fellowship activity. During the weekly meetings, the students discussed service options and planned fellowship activities. Service included such activities as organizing the American Cancer Society’s Relay-for-Life event on campus, mentoring local youth, and helping immigrant families. Fellowship activities were optional and purely social in nature. Intercultural learning, however, is not one of VCSA’s articulated goals nor part of its mission. In fact, the association’s national director was surprised to learn that the individual chapters were fostering meaningful diversity interactions and intercultural relationships. That director recommended the two chapters studied as having heterogeneous membership, enabling interviews with students more likely to have experienced meaningful diversity interactions. The study was originally designed to interview only students and chapter advisors (alumni of the organization). However, following methods of qualitative sampling (Corbin and Strauss, 2008), chapter advisors’ revelations about the postgraduation value of their membership prompted the addition of other alumni to the sample. Members were initially contacted through their chapters’ email lists and chapter advisors. Subsequently, the snowball method was used to identify other respondents, particularly alumni (Hughes et al., 1995). This study was carried out in accordance with the Institutional Review Board of Case Western Reserve University. When interviews were conducted in person, written consent was provided. For interviews conducted by phone, the interviewees gave oral consent to be recorded prior to beginning the interview recording and, subsequently, repeated the oral consent on the recording. In addition, all participants were made aware that their identity would be kept confidential and that their responses would be used for scholarly research purposes only.

Data Collection

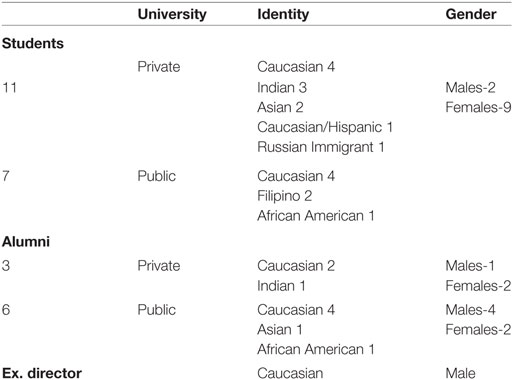

Data were collected using phenomenological interviews (Kvale, 1996; Corbin and Strauss, 2008). During the data collection period, the data were continually analyzed using thematic analysis and code development (Boyatzis, 1998). Throughout the data gathering period, the transcripts were immediately analyzed enabling emerging findings to be substantiated by evidence, the pilot interviews, and the literature, or not. By focusing on the similarities of experiences described by VCSA members, we were able to, according to the study design, identify the components that contribute to association members engaging in meaningful diversity interactions. We sought viewpoints from 26 current or former members of VCSA. Table 1 summarizes the demographics of the interviewees: 11 undergraduates and 3 alumni from a Midwestern private university and 7 undergraduates and 6 alumni from a Southern public university. The sample provided gender and minority/majority ethnic representation: among students, 12 females and 6 males, 8 Caucasians and 10 persons of color (Indian 4; Asian 2, Filipino 2; African American 1; Caucasian/Hispanic 1; Russian immigrant 1); among alumni, five males and four females, six Caucasians and three minorities (Indian 1; Asian 1; African American 1). The alumni graduated between 1981 and 2000. The ultimate size and constitution of the sample, as well as the content of the interviews, was dictated by the evolving data providing theoretical saturation for the data’s emergent themes (Corbin and Strauss, 2008).

Intensive interviews lasting approximately 1 h were conducted, in person or by phone allowed for VCSA members to describe their intercultural interactions. The phenomenological interviews, reflecting the recommendations of Corbin and Strauss (2008) and Kvale (1996), elicited narratives of the interviewee’s actual experiences. Interviews were guided by a semi-structured protocol beginning with “grand tour” questions (Spradley, 1979), leading into open-ended questions and follow-up probes, as necessary. Questions were formulated to enable interviewees to speak freely about their interactions and experiences with students they identified as ethnically and racially different from themselves, within their service organization and elsewhere on campus. They described meaningful interactions that they experienced with such students, including conversations about issues of race/ethnicity and intercultural friendships. Student members were asked (1) to describe a time they worked closely with a person you would consider as different from yourself both inside and outside the service organization; (2) with whom do you mingle with within VCSA and if they ever saw these people outside of VCSA activities; (3) to tell us about more typical everyday experiences experienced on campus with people different from yourself and what distinguishes these experiences with those you have had within VCSA; and (4) how race/ethnicity impacts their interactions with others. In addition, alumni interviewees were asked to reflect on the long-term impact of membership in the service organization on their postcollege lives. Standard qualitative research strategies and protocols (Maxwell, 2005) were adhered to so that biases were eliminated or reduced to the extent possible. All interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim resulting in approximately 700 pages of transcripted interviews, so that the raw data could be systematically analyzed.

Data Analysis

Analysis procedure employed a phenomenological approach (Giorgi, 2009). The inductive approach taken here is consistent with the research goals of this study and with the predominant methodology and assumptions used in similar studies (e.g., Anosike et al., 2012). As per qualitative coding, the data and theory were consistently compared and contrasted throughout the data collection and analysis process (Boyatzis, 1998). This fluidity between data, theory, and the literature resulted in formulation of preliminary categories used to organize the data.

All interviews provided usable data and were included in the analysis. A rigorous coding protocol, requiring multiple readings of each interview transcript, was followed (Boyatzis, 1998). Analysis proceeded concurrently with data collection, facilitating the movement from superficial observations to the more abstract theoretical categories from which findings emerged. This iterative methodology, requiring the constant comparison of data, enabled the researchers to “test” tentative ideas against ongoing observations.

Analysis began with the open-coding of every transcript shortly after each interview. Line-by-line reading strove to identify all phenomena of potential interest and break the data into distinct categories. Student and alumni interviews were analyzed separately, resulting in the initial identification of 40 categories. Subsequently, the codes were iteratively refined, relabeled, and recategorized in a series of steps that revealed patterns in the data (Boyatzis, 1998; Giorgi, 2009). Axial coding confirmed that the identified concepts and categories represented the interview responses accurately and identified those concepts and categories that were related. For theory generation, 20 preliminary organizing categories were identified and similar themes were then grouped together into eight conceptual categories. Continual modification of these categories resulted in the final categories used to frame the coding of the data (Table 2). As each category was refined, the data were reexamined to confirm their final category placement. Approximately 750 excerpts of individual statements were pulled from the transcripts and coded into the final categories. Ultimately, two dominant themes and several subthemes within each constituted the final analysis, presented below. Only subsequent to the emergence of the themes were the concepts of psychological discomfort, intercultural comfort, Gemeinschaft, and appropriable association identified as relevant. These theoretical perspectives helped to integrate and more fully comprehend the entire set of inductively derived themes and subthemes.

Many attempted analyses indicated that the themes did not differ between various possible groupings of interviewees, such as Caucasians and students of color, current students and alumni, and attendees of the two universities. The shared nature of the themes across member groups suggests the power of the association’s practices in creating shared meanings and a morale order.

Findings: Community, Comfort, and Personal Development

You never feel excluded (Indian, Female, Student).

The study’s interviewees provided both a confirmation and a response to Robert Putnam’s warning that “the central challenge for modern, diversifying societies is to create a new, broader sense of ‘we’” (2007:139). Interviewees’ descriptions of their experiences indicated that this challenge was met in VCSA but not elsewhere. The first theme below describes how the association’s practices created among diverse members a close, equal status community where meaningful intercultural ties and comfort developed, enabling interactions that began as bridging to transform into relationships with the qualities normally associated with bonding social capital. The second theme describes how these relationships contributed to the member’s intercultural development.

Theme 1: Experiencing and Overcoming Discomfort in Intercultural Relationships

I would say that it’s definitely changed since high school, and inside [the organization] I’m so much more comfortable because I’ve gotten to know these people so well, and outside of [the organization] I’m slowly starting to be more the way that I am when I’m with [the organization] people, just be more open (Caucasian, Female, Student).

Comparing diversity interactions within VCSA to other groups on campus, one student (Caucasian, Female, Student) explained “it is a lot more comfortable because I know all of the people, and … I … feel as if they are my family. Outside, when I get assigned to a group, I feel a bit more uncomfortable.” Members described outside diversity interactions on campus where they felt “awkward,” “weird,” and “hesitant” due to the need to conform to the norms established by “political correctness,” as some of them described it, behaving in more distant civil ways. Self-monitoring behaviors frequently inhibited individuals from active participation, interfering with discussions about another’s ethnicity or culture for fear of being “offensive” or “breaking a code of conduct.” One student felt that, “With the trend of political correctness it has become inappropriate to talk about how people are different, only how we are all the same.” This was particularly true in larger groups where members expressed a fear of embarrassing themselves. A female, Indian student spoke of the barriers imposed by political correctness: “Sometimes people are a little bit intimidated by asking cultural questions because it’s like, Am I saying it offensively? Am I going to look stupid?” Woven throughout respondents’ accounts are statements about meeting and interacting with diverse others in a genuine, comfortable way, using such terms as “being safe,” “being myself,” and “accepted” to distinguish interactions in which they felt comfortable with others. In summary, the respondents noted that VCSA offered “a comfortable environment for people to express divergent opinions” enabling discussion of sensitive subjects, including cultural and ethnic differences.

The importance of feeling comfort in the service organization was referred to by 22 of 27 respondents. Interviewees implied that feeling comfortable within VCSA facilitated meaningful diversity interactions with culturally different others that might have not developed otherwise. “In our organization we’re all very comfortable with each other” (Caucasian, Female, Student). The more comfortable members reported feeling while engaging in the association’s activities, the more likely they were to ascribe positive meaning to diversity interactions and the more enriching these were reported to be.

At first I probably behaved differently because I didn’t know the people and I was hesitant to get to know all the different people, and then as we were working together a lot more, I became a lot more relaxed and comfortable, and I was able to be myself (Caucasian, Female, Student).

Members reported that comfort in dealing with diverse members extended the relationships beyond formal organizational to personal.

Associational Practices Creating Community and Comfort

It didn’t really occur to me that there were mostly white people or that anyone was different from me really. Cause we’re all there for the same purpose and that was service and the races or the ethnicities are not in the forefront of my mind (African American, Female, Student).

Shared Purpose

The importance of common interest in volunteering as a foundation for meaningful intragroup relationships was emphasized by 21 of 27 respondents. Performing service, identified by most interviewees as the motivation for joining the organization, provided an impetus for interaction. One student emphasized, “We all have common interest in doing [the] work, so that’s the big thing (Asian, Male, Student).” Majority and minority members credited the sense of purpose as more significant for facilitating conversations and building meaningful diversity interactions than commonality of skin color, cultural, or ethnic background, indicating that VCSA inspired a sense of community that transcended cultural differences among members. An alumna reflected that, “People come together, not with their cultures, but the fact that their common interest is volunteering (Asian, Female, Student).” Minority group members within the organization who chose not to join racially or ethnically segregated groups on campus cited the absence of a sense of purpose, beyond socializing, as a reason for not joining those groups.

Mission-Based Welcoming

It was like an open door, so welcoming. I mean, they really don’t have a strict way of taking members, as long as you are willing to give back to the community … It was more of a family, an open-arms community. It was very welcoming (African American, Male, Alumnus).

The diversity of the chapter members was cited by 20 of 27 respondents as positively impacting their ability to meet and befriend diverse others. VCSA’s official policy is inclusive: “everybody’s welcome” who is committed to the mission of community service. Any student willing to commit to the pledge process, weekly meeting, and community service obligation is accepted into membership. Some members joined because the organization “had a … good history … of being accepting of other people (Filipino, Male, Student).” Although both universities in the sample had ethnically heterogeneous student bodies, interviewees revealed difficulty in meeting and experiencing meaningful interactions with diverse others prior to joining the service organization. This was attributed to the belief that “the ethnic groups stay together. But, not the [members of VCSA]” (Caucasian, Female, Student). Interviewees emphasized that because “its focus isn’t as a cultural organization” (Asian, Female, Student), such as the Asian Student Association, an environment was created wherein enriching diversity interactions could flourish.

Welcoming practices were similar to, and even went beyond, those in some Greek social fraternities common at American universities. Each pledge was “forced to know everyone because during your pledging process you had to interview everyone,” causing new members to “learn about and get to know someone from a different background …” (African-American, Male, Alumnus). This was often the first time the students had an in-depth interaction with someone of a different cultural or ethnicity, and was frequently cited as both impactful and significant. Once potential new members “pledged,” they attended weekly meetings (sitting in a circle), completed a mission-oriented service project as a group, and were assigned “big brothers” using an ethnicity-blind method. As one member observed, “My big brothers … act[ed] as mentors … you’re kind of a little family unit” (Caucasian, Male, Student). Mentoring created a mechanism for in-group networking, “Because I became friends with [my big brothers] I then became friends with their friends … and I got to be friends with a lot of people” (Caucasian, Female, Student).

Promoting Fellowship through Interaction Structuring

At first, I was like, okay, so we’re working together. This is like every other club. You work together. It doesn’t necessarily mean anything. But as we were working together, we started opening up about things out of her life and I kind of realized they’re not exclusive. Becoming friends and working together on a club are not exclusive. This was highly unexpected (Indian, Female, Student).

Our data indicated the importance of fellowship in fostering an identity with all community members, irrespective of background. Interviewees noted several fellowship-promoting practices: rotation of members in committee assignments and when performing service; providing mentors for new members; deliberate clique reduction; and planning recreational social activities. These practices of structuring interactions enabled group members to spend “so much time in so many different ways together” (Caucasian, Male, Alumnus). All 27 of the respondents attested to the solidarity, acceptance, and fellowship they felt in VCSA, confirming the effectiveness of these interaction structuring practices.

Members of diverse cultures, race, or ethnicity met and engaged with one another through “structured weekly meetings, playing icebreakers, but mostly because [of the] structured, planned fellowship” (Caucasian, Female, Student). One Asian, male, alumni explained, “You’re constantly interacting … onstant socialization on a day-to-day basis.” VCSA’s effort to build personal relationships is reflected in the positioning of fellowship as one of the association’s central tenets, because, as VCSA’s executive director explained, “without the fellowship, you have nothing.”

Rotating committee assignments and leadership positions every semester ensured that no subgroup developed “power” over another. Respondents stressed the importance of maintaining equal member status, a condition they found lacking in social fraternities and other campus groups, contributed to a strong group identity and mutual respect in VCSA.

Fellowship meant a brotherhood with all, not restricted to subgroups. A student leader emphasized that VCSA does not “… want you to start cliques. That goes with the brotherhood” (Indian, Female, Student). The practices by which groups were formed for service projects—using signup sheets and emails—meant that individuals spent time with an ever-changing set of members while performing service work. Working together “brought us close together even if it was with a different group of people each time we went” (African American, Female, Student). This recategorization of the membership into a group identity on a basis other than culture or ethnicity “forced … you to become interpersonal” (African-American, Male, Alumnus). None of the respondents expressed a hesitancy to intermingle, instead revealing that being “forced” together created a positive opportunity to interact with different people and form relationships. According to one student, “I met him because I was forced to meet him. In turn we developed a relationship, a friendship out of it, and it’s been a great experience” (Caucasian, Female, Student).

Interviewees contrasted their in-group experiences with those they experienced in other campus associations where interaction structuring practices were absent and student hierarchy, subgroup homogeneity, and cliques were present, “The emphasis is on the personal connections to the group. This I did not experience in any of the other groups that I was part of” (Caucasian, Female, Alumnus). This suggests that simply being a member in “other groups” did not ensure formation of close relationships.

Sense of Belonging

I joined up initially for the community [service] and to meet other people. But right now, I’m finding there’s the whole thing where you do the community service, but you stay for the fellowship (Hispanic-Irish, Female, Student).

Voluntary community service association’s intentional adoption of interaction structuring practices that facilitated inclusive socialization and fellowship produced a strong collective identity. The respondents unanimously attributed solidarity and acceptance as benefits of membership. One respondent expressed, “You join for the service, but stay for the brotherhood.” Making service enjoyable enabled the association to attract and retain members. For many members, having “fun” was an unexpected outcome of membership. Respondents commented on the social benefits, noting, “you’re doing service, but you’re also trying to have a good time” (Caucasian-Hispanic, Female, Student). These comments are indicative that members appropriated VCSA to serve their social needs.

The emphasis on fellowship and brotherhood was reported to create an enjoyable, safe, and comfortable environment, interpreted by members as unique. In other organizations, an alumnus recalled, “We never spent time developing the brotherhood feeling. [Here] there is inclusion … tolerance and being kind to everyone” (Caucasian, Male, Alumnus). A current student member explained, “We’ll step up for each other and [the organization] is the only experience I’ve had that” (Indian, Female, Student). Such comments suggest that intercultural inclusion is the result of practices that, among others, foster insider status and information sharing among all members, fostering a sense of belonging.

As a whole, the students’ experiences differentiated their service association from other settings on campus in its ability to overcome intercultural communication apprehension and discomfort. While a shared mission brought them together into a heterogeneous membership, it was a combination of practices institutionalized in VCSA and not experienced elsewhere that created conditions of comfort, equal status, and belonging able to sustain their diversity interactions.

Theme 2: Personal Development As a Product of Comfort

I just like learning and getting to know people, and it just makes you realize that the world is such a huge place and that we all come from such different backgrounds with different values, goals, and directions. At the same time, you can always find common ground amongst the differences, and that’s something great to learn (Caucasian, Female, Student).

Learning from Different Others

Learning while engaged in service activities, on committees, in leadership positions, and interpersonally was described in detail by 24 of 27 respondents. The most common theme was learning from each other, “I’m constantly learning something. I feel I wouldn’t be the same person if I couldn’t share the different cultural aspects of each of the close friends I have that are of different ethnicities” (Asian, Female, Student). While collaboratively “working on service projects, you learn a lot about different people” (Caucasian, Female, Student), the community—and, they revealed, themselves. Learning from others was a primary reason they were able to overcome the awkwardness and discomfort they initially felt toward those of different races and cultures, and ultimately engage in additional diversity interactions. One Caucasian, female, student explained,

On every service project I learned something new either about myself or someone else in the group, or I learned something about the community, or I learned a skill … I’m more able to interact with people that are different from me because I’ve learned so much about people in [the organization].

The impact of experiencing cross-ethnic interactions was expressed by another student, “There are a couple of instances where because of people’s backgrounds I thought they were just going to be like sort of ignorant. And then I, in turn, was actually the ignorant one” (Caucasian, Male, Student).

Members in the close community of this association experienced attitudinal change as a result of their experiencing mutual comfort, direct interactions, and observations.

I am so grateful because I feel if I hadn’t been able to work with people that are different than I am on service projects I would be missing out, and I’m not exactly sure what my personality would be like today had I not had those experiences and feel as comfortable as I do (Caucasian, Female, Student).

Interviewees’ narratives suggested that learning interactions, once experienced, fortified intercultural comfort, increasing the likelihood of experiencing additional meaningful diversity interactions.

Transcending Ethnic Differences

I’m really happy for these opportunities to meet new people … I’ve gone home, people talk about the college they go to, and–there’s not a lot of diversity. Their group of friends back in college is, basically, one race. I feel like there is a disconnect. Some of my friends, I’m not friends with now, from high school because I feel like they didn’t grow up. They haven’t opened their minds to other things (Caucasian, Female, Student).

Engaging in enriching and bonding diversity relationships, members learned about cultural and ethnic differences and experienced a basic connecting with another as a human. Transcendence was achieved when members were able to move beyond their cultural differences to identify human commonalities. Of the respondents 16 of 27 (eight Whites and eight racial/ethnic minorities) reported not seeing a “difference between … different [others].” By not “classifying people by race or whatever” and “seeing everyone individually” the interviewees expressed the idea of getting “to know each other for who they are, not for the color of their skin.” According to one female, student of color, “When I’m in a very diverse group of people, it doesn’t occur to me that we’re all from different races” and an Asian, male, student “When I meet a new member … it has nothing to do with their race any more …” A female, African-American student explained that if she had “… a positive relationship or … interaction with somebody … race just isn’t really a part of it.” And, a female, Asian student noted that she didn’t “see a difference … even though we are people from different cultures—I think all of us are pretty [much] the same. We interact the same way with each other.” This suggests that transcending cultural and ethnic differences and identifying human commonalities, in the context of shared purpose within a close community, contributed to a decrease in stereotypes and tensions, enabling members to participate more comfortably in diversity interactions. These experiences led a Russian female student to report, “It feels empowering, I can overcome these racial barriers that our parents, our grandparents have had. I’m better than that. I can think beyond that, so I feel proud for that.” Unlike guarded diversity interactions in the general university environment, comfortable interactions within VCSA enabled members to learn about each other, transcend differences, and experience the personal development that occurs in meaningful diversity interactions.

Discussion

To address the gap in knowledge of the social determinants of meaningful, learning diversity interactions on campus, we reviewed several bodies of literature and conducted intensive phenomenological interviews. The study’s findings enabled us to distinguish practices of meaningful intercultural interactions in contexts where personal, equal-status, ethnically heterogeneous ties and learning are found from those in other campus contexts. Drawing on the findings, we provide new knowledge of two inter-related phenomena: (1) the role of intercultural comfort in fostering sustained developmental interactions and (2) the social practices that lead to intercultural comfort.

The Concept of Intercultural Comfort

The intercultural comfort described by this study’s interviewees can contribute to a campus society that respects differences and builds social ties across diverse groups, producing developmental benefits. A feeling of belonging and social identification with VCSA’s members created a perception of similarity strongly related to feelings of safety and comfort (Rodriguez, 1982; Honneth, 1995; Noble, 2002). The desire to belong drives people to seek frequent, positive interactions with others within a stable, long term, and caring context (Baumeister and Leary, 1995), forming personal, Gemeinschaft-like social ties with diverse others. Students’ experiences point directly to intercultural comfort as the condition that differentiated an associational setting that produced meaningful diversity interactions from most other campus environments. This finding is consistent with the more general concept of interpersonal comfort.

For individuals’ personal development, interpersonal comfort facilitates learning, building social competence and bolstering one’s sense of efficacy (Jones, 1995). Comfort reflects a practical consciousness and ontological security (Giddens, 1990) in the specific social setting—here, the service association—that results in an ability to accommodate oneself and produce appropriate responses with different others (Noble, 2005). Self-efficacy develops over time through repeated task-related experiences and as new information and experiences are acquired (Gist and Mitchell, 1992), enabling individuals to become more flexible, adaptable, and able to adopt appropriate behaviors when engaged in diversity interactions.

According to this study’s analyses of young adults’ associational experiences, intercultural comfort underlies the development of intercultural learning and attitudinal change. For further inquiry, we propose a definition of intercultural comfort consistent with the literature on interpersonal comfort cited above: Intercultural comfort is the felt ease, safety, and self-efficacy of interacting appropriately with ethnically different others. Future research can explore the adequacy of this definition and comfort’s role at the individual and associational levels in producing and sustaining diversity interactions.

Social Practices for Intercultural Comfort and Interaction

The study’s findings indicate that fostering intercultural comfort for high frequency, meaningful diversity interactions is possible in particular associational settings on campus. However, extending prior research on conditions that favor positive cross-ethnic contact and attitude change (Allport, 1954; Pettigrew, 1998), the findings also suggest that such an achievement is contingent on associational practices that go well beyond the usual bounds of civility. At the institutional level, civil norms of tolerant but superficial interaction produced, as we were initially somewhat surprised to find from our interviewees’ descriptions of their experiences, discomfort that matched the concept of intercultural communication apprehension (Kim, 2012). The apprehension was sufficient to inhibit meaningful interaction and learning. Interviewees also reported that associations on campus whose formal purposes were social, failed to overcome this intercultural discomfort, and were largely homogeneous. This failure is consistent with findings that participation in leisure and recreational associations have, at best, marginal value in contributing to the civic development of youth (Cicognani et al., 2015).

How, then, were meaningful diversity interactions fostered for new members of VCSA and sustained for older members? As is clear from this study’s emergent themes, a number of social practices were involved: welcoming a diverse membership on the basis of commitment to a mission; promoting interactions through required personal conversations between new and existing members; discouraging cliques; rotating leadership for equal status and hierarchy reduction; interaction structuring that continually mixed individuals who participated alongside each other in the organization’s activities; weekly social activities for all members; and providing mentors to new members. Of these, interaction structuring and equal status are particularly important to intercultural tie creation and the repetition of meaningful diversity interactions for personal development. Once a spirit of fellowship is engendered through various practices, a social structuring that rotates leadership helps to confer equal status. In turn, equal status facilitates individuals’ willingness to respect and learn from each other’s experiences through the types of conversations described by the interviewees. The students reported that these conversations often occurred during service activities. The social structure of these activities, the interaction structuring, ensured that each member met a variety of different members over the course of a year’s activities, enabling a larger number of intercultural ties to form and new experiences to be discussed.

Such interaction structuring practices fit with Park and Bowman’s (Park and Bowman, 2015) model of skill development: a relatively large number of intercultural ties, more weak than bonding, with each tie providing the opportunity for novelty in meaningful experiences. In addition, some members reported stronger ties of friendship, more bonding than weak. This is consistent with Moody (2001) who, in a study of middle and high school students, found that opportunity for intercultural mixing (Blau, 1977) was most significant for decreasing friendship segregation and increasing cross-race friendship ties. Race of one’s roommate, degree of interracial contact in residence halls, and participation in various types of extracurricular activities are most strongly related to the formation of interracial friendships (Stearns et al., 2009). The opportunity for close interactions with students of other races is positively related to both interracial friendships and cross-racial interactions (Bowman and Park, 2014), consistent with the formation of both strong and weak intercultural ties in the service association. While differences may exist in the roles that strong and weak ties serve, the important point is that VCSA provided the opportunity for a high frequency of positive, respectful diversity interactions. The ties were formed in a climate of fellowship, enabling more of the interactions to be comfortable and, so, repeated. The repetition enabled personal development to proceed over time.

The social practices that enabled VCSA members to build intercultural comfort and overcome communication apprehension, when combined with the association’s mission, produced conditions known to favor positive contact (Allport, 1954; Pettigrew et al., 2011), particularly the conditions of shared goals, interdependence, and equal status. Similarly, they sustained Crisp and Turner’s (Crisp and Turner, 2011) four conditions for intercultural learning: perceptions of stereotype inconsistencies; motivation to engage; ability to engage; and repetition. Regarding stereotype inconsistencies, the service organization’s mission and interaction practices, as noted above, created frequent interactions among diverse members. Seeing each person as an individual with a range of human characteristics, not simply as a cultural stereotype, created the opportunity to realize one’s stereotype inconsistencies. Regarding motivation, the VCSA’s Gemeinschaft-like emphasis on fellowship among all members, including its welcoming practices, discouragement of cliques, and rotation of leadership roles, provided positive emotions to engage in, rather than avoid, communications with different others. Regarding ability, VCSA’s close community and shared identity created the ability, in terms of comfort, to not only learn about but also respect others’ experiences, values, and interpretations. Regarding repetition, VCSA’s mission and social activities, interaction structuring practices, and close community norms provided members with repeated meaningful diversity interactions over several years’ time. That the themes of this study did not differ between minority and majority members suggests that these repeated interactions led to shared meanings concerning salient experiences on campus, such as the role of political correctness norms in hampering cross-cultural interactions. Interviewee statements echoed arguments that political correctness inhibits the development of trust between ethnically different group members by discouraging frank discussion, leaving individuals fearful of hidden thoughts and limiting the desire for further interactions (Ely et al., 2006; Jackson, 2008). In sum, the otherwise discomforting process of recognizing stereotype inconsistencies and their accompanying challenges to one’s self-identity (Zaharna, 1989) was steered toward cultural learning by social practices that repeatedly engendered the conditions of shared goals, common identity, fellowship, equal status, and interpersonal comfort.

The associational setting for these practices was a contributing factor to continued diversity interactions. VCSA was appropriated (Coleman, 1988) by this study’s interviewees as a vehicle for meaningful diversity interactions and learning, though such was not the association’s purpose. Students joined for its service mission but remained due to its fellowship. Its community service purpose, however, was important. It carried an other-regarding focus reflective of service learning projects that have positive impact on students’ civic responsibility (Braunsberger and Flamm, 2013) and awareness of diversity. This other-regarding associational purpose was combined with practices that fostered the development of close community, creating the social closure identified by Coleman (1988) as necessary for appropriating an organization for uses unrelated to its original purpose. Associational practices that created a close, equal status community with a shared moral culture institutionalized member behavior in a manner that preserved conditions for positive contact, enabling members to have informal but serious conversations regarding their backgrounds and experiences. That these conversations developed in the social context of VCSA’s moral order accords with Etzioni’s (Etzioni, 2001) assessment that moral order is necessarily the first step in building the trust and social capital that Putnam (2000) attributes to social networks, here with regard to high-quality, cross-cultural ties. Associating around a shared purpose enabled VCSA’s members to reduce segregation (Stark and Flache, 2012) and build common bonds, goals, and values consistent with Brint’s (Brint, 2001) view that common experiences enable the development of strong ties and concern for one another, ties commonly associated with bonding social capital.

Practices for Sustaining Culturally Diverse Close Community

Based on this study and prior research, we propose that particular types of associational settings, and not others, contribute to intercultural comfort, cross-ethnic relationships, and cultural learning. Such settings are characterized by particular purposes and social practices that sustain favorable conditions for high-quality, meaningful diversity interactions. While this study was limited to two chapters of one voluntary association, analyses by Brint (2001) and Vaisey (2007) identify similar associational characteristics that sustain close community. Brint distinguishes “voluntaristic” practices that favor the creation of societally favorable virtues, such as intergroup respect, from “sacrificial” practices, including hazing, that favor vices such as intergroup intolerance (2001:18). Drawing on our findings and Brint’s hypotheses, we offer two propositions as a potential stimulus to further research and policy formation, premised on promoting the moral order necessary to sustain intercultural comfort and interactions. The propositions are further premised on a diverse population in the general institutional setting and an underlying civil behavior and discourse, even if relatively superficial, among its different ethnic groups. Proposition 1 points to specific social practices related to intercultural comfort.

Proposition 1 Practices creating comfort in intercultural interactions: The association facilitates the formation of intercultural comfort by making membership open to all based on commitment to the pledge process, acceptance of the community service mission, fellowship of the whole, meeting attendance, the use of rituals, establishment of common meeting places for formal and informal interactions to occur, the structuring of interactions in such a way as to bring culturally different members into frequent contact, intolerance of cliques, and avoiding hazing and dress or expression requirements.

Proposition 2 builds on the association’s practices that promote diversity interactions by establishing a moral order that makes the organization inviting to all students and that facilitates repeated and comfortable diversity interactions.

Proposition 2 Practices sustaining a respectful moral order: Once culturally diverse members join, the association promotes meaningful, repeated, diversity interactions through continuous pursuit of a shared mission serving other’s interests, not merely their own. The association institutionalizes practices that focus members on formal purposes other than diversity, maintain a small organizational size, and create equality in knowledge, power, and authority.

Campus Policies: Appropriating Organizations for Cultural Learning

To expand theory and action for meaningful diversity interactions, this study indicates the promise of focusing on institutionalized practices that can overcome impediments of discomfort and self-segregation. This study’s central concept, intercultural comfort, and concepts of close communities and socially appropriable organizations suggest several avenues for new institutional policies. Many contemporary policies fail to consider comfort and thereby provide too few of the conditions (shared purpose, interdependence, equal status) specified by Allport (1954) and others, and too few of the resources (motivation, ability, and repetition) specified by Crisp and Turner (2011) as necessary for working through cross-cultural stereotypes and discomfort. The repetition of intercultural interaction necessary for overcoming discomfort and producing personal development calls for a social structure. The present study indicates that the structure of a voluntary association can provide such repetition. Research reviewed above points to particular extracurricular activities as an associational focus for intercultural interaction and learning. Those findings are supported and extended by this study, as they are also by Coleman’s (Coleman, 1988) concept of appropriable organizations. Wherever students from different ethnic backgrounds come together to seriously pursue a shared objective, they have the opportunity to appropriate the mission-focused social capital they generate, using it to pursue their own social and developmental needs. The reported experiences are consistent with arguments that cultural learning, which depends on sustained, reflective individual and collective social experiences (Brewer, 1996; Gaertner et al., 1996), is a significant step toward building meaningful diversity interactions at the individual level and experiencing and appreciating cultural and ethnic heterogeneity at the group level (Weisinger and Salipante, 2005; Ely et al., 2012).

This study’s findings suggest that institutions of higher education have two broad options for creating associational settings where practices favor intercultural ties and their associated personal development: (1) make existing homogeneous social institutions, such as traditional Greek societies, more heterogeneous by supporting practices that favor intercultural comfort or (2) promote and appropriate student associations that attract a heterogeneous membership. Our findings suggest a distinctive advantage for the second option due to the attraction and shared pursuit of a formal purpose other than social. In such a purpose-driven context, this study indicates that particular practices of association—practices that produce conditions, such as fellowship and equal status, and practices that can be promoted by an institution as part of its core values—can create a moral order that sustains repeated, meaningful diversity interactions and consequent learning.

The phenomenon of individuals appropriating an association for meaningful diversity interactions and relationships can, in turn, be appropriated for institutional strategy. Educational institutions have resources to promote the development of associations that attract students on bases other than ethnicity, such as this study’s service organization. Many types of extra- and co-curricular activities qualify, such as intercollegiate engineering and athletic competitions, performing arts, clubs focused on particular interests and academic disciplines, and many varieties of community service. However, as students in this study indicated, such activities often lack the practices for fellowship and equal status that distinguished VCSA. Hence, campus policies could seek to inculcate in these activities social practices that promote repeated, comfortable, equal status interactions among interdependent members, forming small, close, heterogeneous communities.

Three contemporary trends in secondary and higher education offer loci for inquiring into the propositions offered above and for implementing and evaluating new policies. First, institutions are striving to improve student life by promoting student self-formation of groups around extracurricular interests (Cheng and Zhao, 2006). Second, many institutions are promoting service learning, creating the possibility, as in this study, for students to associate long term around their service activities (Eyler, 2000). Third, some institutions are building an institutional diversity among their student bodies through the promulgation of values-based practices, such as team-building (Kuh, 1991). Both inquiry and policy formation can mate with these trends to expand knowledge of where and how enriching diversity interactions are occurring and can be promoted further.

The recurrence of ethnic tensions on campus and elsewhere is a signal to researchers and leaders that new knowledge is needed. The present research suggests the value of applying and extending established social concepts by inquiring into naturalistic processes that produce and sustain high-frequency, meaningful diversity interactions and personal development in particular campus settings. The resulting knowledge can guide the intentional, synthetic formation of close, heterogeneous communities on campus in which fellowship and comfort enable individuals to learn from their differences.

Ethics Statement

This study was carried out in accordance with the Institutional Review Board of Case Western Reserve University. All interviewees gave consent to be recorded, were made aware that their identity would kept confidential, and that their responses would be used for scholarly research purposes only.

Author Contributions

RB conducted the qualitative interviews and coded the data. PS contributed to the theoretical framework. Together RB and PS wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Anosike, P., Ehrich, L. C., and Ahmed, P. (2012). Phenomenology as a method for exploring management practice. Int. J. Manag. Pract. 5, 205–224. doi: 10.1504/IJMP.2012.048073

Antonio, A. L. (2001). Diversity and the influence of friendship groups in college. Rev. Higher Educ. 25, 63–89. doi:10.1353/rhe.2001.0013

Baumeister, R. F., and Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol. Bull. 117, 497–529. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

Bowman, N. A. (2010). College diversity experiences and cognitive development: a meta-analysis. Rev. Educ. Res. 80, 4–33. doi:10.3102/0034654309352495

Bowman, N. A. (2012). Promoting sustained engagement with diversity: the reciprocal relationships between informal and formal college diversity experiences. Rev. Higher Educ. 36, 1–24. doi:10.1353/rhe.2012.0057

Bowman, N. A. (2013). How much diversity is enough? The curvilinear relationship between college diversity interactions and first-year student outcomes. Res. Higher Educ. 54, 874–894. doi:10.1007/s11162-013-9300-0

Bowman, N. A., and Denson, N. (2011). The integral role of emotion in interracial interactions and college student outcomes. J. Divers. Higher Educ. 4, 223–235. doi:10.1037/a0024692

Bowman, N. A., and Park, J. J. (2014). Interracial contact on college campuses: comparing and contrasting predictors of cross-racial interaction and interracial friendship. J. Higher Educ. 85, 660–690. doi:10.1353/jhe.2014.0029

Bowman, N. A., and Park, J. J. (2015). Not all diversity interactions are created equal: cross-racial interaction, close interracial friendship, and college student outcomes. Res. Higher Educ. 56, 601–621. doi:10.1007/s11162-015-9365-z

Braunsberger, K., and Flamm, R. O. (2013). A mission of civic engagement: undergraduate students working with nonprofit organizations and public sector agencies to enhance societal wellbeing. Voluntas 24, 1–31. doi:10.1007/s11266-012-9289-6

Brewer, M. B. (1996). When contact is not enough: social identity and intergroup cooperation. Int. J. Intercult. Relations 20, 291–303. doi:10.1016/0147-1767(96)00020-X

Brint, S. (2001). Gemeinschaft revisited: a critique and reconstruction of the community concept. Sociol. Theory 19, 1–23. doi:10.1111/0735-2751.00125

Chang, M. J., Astin, A. W., and Kim, D. (2004). Cross-racial interaction among undergraduates: some consequences, causes, and patterns. Res. Higher Educ. 45, 529–553. doi:10.1023/B:RIHE.0000032327.45961.33

Cheng, D. X., and Zhao, C. M. (2006). Cultivating multicultural competence through active participation: extracurricular activities and multicultural learning. NASPA J. 43, 13–38.

Cicognani, E., Mazzoni, D., Albanesi, C., and Zani, B. (2015). Sense of community and empowerment among young people: understanding pathways from civic participation to social well-being. Voluntas 26, 24–44. doi:10.1007/s11266-014-9481-y

Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am. J. Sociol. 94(Issue Suppl.), S95–S120. doi:10.1086/228943

Crisp, R. J., and Turner, R. N. (2011). Cognitive adaptation to the experience of social and cultural diversity. Psychol. Bull. 137, 242. doi:10.1037/a0021840

Denson, N., and Bowman, N. (2013). University diversity and preparation for a global society: the role of diversity in shaping intergroup attitudes and civic outcomes. Stud. Higher Educ. 38, 555–570. doi:10.1080/03075079.2011.584971

Denson, N., and Chang, M. J. (2009). Racial diversity matters: the impact of diversity-related student engagement and institutional context. Am. Educ. Res. J. 46, 322–353. doi:10.3102/0002831208323278

Ely, R. J., Meyerson, D. E., and Davidson, M. N. (2006). Rethinking political correctness. Harv. Bus. Rev. 84, 78–87.

Ely, R. J., Padavic, I., and Thomas, D. A. (2012). Racial diversity, racial asymmetries, and team learning environment: effects on performance. Organ. Stud. 33, 341–362. doi:10.1177/0170840611435597

Etzioni, A. (2001). Is bowling together sociologically lite? Contemp. Sociol 30, 223–224. doi:10.2307/3089233

Eyler, J. S. (2000). What do we most need to know about the impact of service-learning on student learning? Mich. J. Community Serv. Learn. 11–17.

Gaertner, S. L., Dovidio, J. F., and Bachmnan, B. A. (1996). Revisiting the contact hypothesis: the induction of a common identity ingroup identity. Int. J. Intercult. Relations 30, 271–290. doi:10.1016/0147-1767(96)00019-3

Gaertner, S. L., Mann, J., Murrell, A., and Dovidio, J. F. (1989). Reducing intergroup bias: the benefits of recategorization. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 57, 239–249. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.57.2.239

Giorgi, A. (2009). The Descriptive Phenomenological Method in Psychology: A Modified Husserlian Approach. Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press.

Gist, M. E., and Mitchell, T. R. (1992). Self-efficacy: a theoretical analysis of it determinants and malleability. Acad. Manag. Rev. 17, 183–211. doi:10.5465/AMR.1992.4279530

Halualani, R. T. (2007). How do multicultural university students define and make sense of intercultural contact? A qualitative study. Int. J. Intercult. Relations 32, 1–16. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2007.10.006

Harrison, D. A., Price, K. H., and Bell, M. P. (1998). Beyond relational demography: time and the effects of surface-and deep-level diversity on work group cohesion. Acad. Manag. J. 41, 96–107. doi:10.2307/256901

Hughes, A. O., Fenton, S., Hine, C. E., Pilgrim, S., and Tibbs, N. (1995). Strategies for sampling black and ethnic minority populations. J. Public Health Med. 17, 187–192. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.pubmed.a043091

Hurtado, S. (2005). The next generation of diversity and intergroup relations research. J. Soc. Issues 61, 595–610. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.2005.00422.x

Jackson, J. L. (2008). Racial Paranoia: The Unintended Consequences of Political Correctness. New York, NY: Basic Civitas Books.

Kim, M. S. (2012). Cross-cultural perspectives on motivations of verbal communication: review, critique, and a theoretical framework. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc. 22, 51–89. doi:10.1080/23808985.1999.11678959

King, P. M., Perez, R. J., and Shim, W. J. (2013). How college students experience intercultural learning: key features and approaches. J. Divers. Higher Educ. 6, 69. doi:10.1037/a0033243

Kuh, G. (1991). Involving Colleges: Successful Approaches to Fostering Student Learning and Development outside the Classroom. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Kvale, S. (1996). Interviews: An Introduction to Qualitative Research Interviewing. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Lazarsfeld, P. F., and Merton, R. K. (1954). Friendship as a social process: a substantive and methodological analysis. Freedom Control Mod. Soc. 18, 18–66.

Lin, Y., and Rancer, A. S. (2003). Ethnocentrism, intercultural communication apprehension, intercultural willingness-to-communicate, and intentions to participate in an intercultural dialogue program: testing a proposed model. Commun. Res. Rep. 20, 62–72. doi:10.1080/08824090309388800

Magis, K. (2010). Convergence: finding collective voice in global civil society. Voluntas 21, 317–338. doi:10.1007/s11266-009-9107-y

Maxwell, J. A. (2005). Qualitative Research Design: An Interactive Approach, Vol. 41. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

McCabe, J. (2011). Doing multiculturalism: an interactionist analysis of the practices of a multicultural sorority. J. Contemp. Ethnogr. 40, 521–549. doi:10.1177/0891241611403588

McPherson, M., Smith-Lovin, L., and Cook, J. M. (2001). Birds of a feather: homophily in social networks. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 27, 415–444. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.415

Milem, J. F., Chang, M. J., and Antonio, A. L. (2005). Making Diversity Work on Campus: A Research-Based Perspective. Washington, DC: Association American Colleges and Universities.

Moody, J. (2001). Race, school integration, and friendship segregation in America. Am. J. Sociol. 107, 679–716. doi:10.1086/338954

Moss-Racusin, C. A., van der Toorn, J., Dovidio, J. F., Brescoll, V. L., Graham, M. J., and Handelsman, J. (2014). Scientific diversity interventions. Science 343, 615–616. doi:10.1126/science.1245936

Neuliep, J. W., and McCroskey, J. C. (1997). The development of a US and generalized ethnocentrism scale. Commun. Res. Rep. 14, 385–398. doi:10.1080/08824099709388682

Neuliep, J. W., and Ryan, D. J. (1998). The influence of intercultural communication apprehension and socio-communicative orientation on uncertainty reduction during initial cross-cultural interaction. Commun. Q. 46, 88–99. doi:10.1080/01463379809370086

Noble, G. (2002). Comfortable and relaxed: furnishing the home and nation. Continuum J. Media Cultur. Stud. 16, 53–66. doi:10.1080/10304310220120975

Noble, G. (2005). The discomfort of strangers: racism, incivility and ontological security in a relaxed and comfortable nation. J. Intercult. Stud. 26, 107–120. doi:10.1080/07256860500074128