Learning Transfer: The Missing Link to Learning among School Leaders in Burkina Faso and Ghana

- Leadership, University of San Diego, San Diego, CA, United States

Every year, billions of dollars are spent on development aid and training around the world. However, only 10% of this training results in the transfer of knowledge, skills, or behaviors learned in the training to the work place. Ideally, learning transfer produces effective and continued application by learners of the knowledge and skills they gained through their learning activities. Currently, there is a limited body of research examining the factors that hinder and promote learning transfer in professional development, particularly the professional development of school leaders in developing countries. This qualitative exploratory study sought to address the gap in the literature by examining six schools: three in Burkina Faso and three in Ghana, West Africa. This investigation explored what promoted and hindered learning transfer in both countries. The sample consisted of 13 West-African school leaders (6 in Burkina Faso and 7 in Ghana) who attended a 3-day leadership training workshop. Data collection included in-depth interviews, document analysis, post-training site visits, and text messages to ascertain whether this mobile technology intervention enhanced learning transfer. The findings demonstrated that learning transfer occurred in both countries in all six schools. Data indicated that most of the transfer of learning happened in areas not requiring mindset and behavioral changes. Data suggested that the facilities in which the trainings took place, the facilitators’ dispositions and knowledge, the adequacy of the materials as well as the testimonials and certificate of completions enhanced the transfer of learning. Participants also indicated some inhibitors to the transfer of learning, such as financial, cultural, and human behavior constraints. This study helps increase our understanding of what promotes and inhibits learning transfer in educational settings in Burkina Faso and Ghana and provides suggestions for trainers and teachers who facilitate trainings.

Introduction

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) seek to continue alleviating poverty and hunger, protecting the environment as well as promoting health and education. In terms of education the SDGs focus not only on access to primary education for all but they also aim to help provide quality education in primary as well as secondary schools around the developing world (United Nations, 2016). Due to the fragility of many public educational systems, many developing nations have seen a rapid increase in the growth of low-fee private schools (LFPSs). Researchers such as Grissom and Harrington (2010) and Leithwood et al. (2004) have demonstrated that training the school leadership team is fundamental to improving learning and transferring knowledge (Leithwood et al., 2004; Grissom and Harrington, 2010; Swaffield et al., 2013). However, to date, little has been done to improve the school leadership teams in Africa, particularly in West Africa (Bush and Oduro, 2006; Bush et al., 2011).

Despite the $921 million spent on education in Africa between 2010 and 2012, there is little evidence that the monies invested yielded improved student learning outcomes [United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (2015, UNESCO)]. This illustrates, in part, the lack of understanding and focuses that governments, policy makers, educators, facilitators, and trainers have placed on training and learning transfer (Ford, 1994; Awoniyi et al., 2002). Oftentimes programs are not adapted to the participants’ needs and do not take into account how adults learn best (Knowles, 1980; Mezirow, 2000). In addition, trainings do not often take into consideration the local context and culture [Central Intelligence Agency (2016, CIA)]. Rather, trainers must take into consideration learning transfer before, during, and after the trainings take place. Activities and pedagogies that are culturally responsive and adapted foster learning transfer. Post-training follow-up and adequate conditions for learning also enhance learning transfer.

The purpose of this study was to examine what inhibited and enhanced the transfer of learning in Burkina Faso and Ghana after a professional development event attended by school principals and owners of LFPSs. The research question examined was: What enhanced and hindered the transfer of learning post professional development event to the LFPSs? The key findings suggest that the unique cultural circumstances of each country prevented the transfer of learning. Other findings pointed out that testimonials and certificates of completion promoted learning transfer. This study is particularly salient in its contribution to the literature because it provides insights on learning transfer that are not only relevant for West Africa but also for school leaders in all developing countries. In this article, first we explain the concept of transfer of knowledge as it relates to adult learning. The next section examines the literature on what hinders learning transfer in general and in developing countries. In the third section, the approach to conducting the study is presented followed by the factors that promote learning transfer. We conclude by addressing the relevance of the findings for practitioners, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), governments, and policy makers.

Learning transfer is defined as “the effective and continuing application by learners—to their performance of jobs or other individual, organizational, or community responsibilities—of knowledge and skills gained in the learning activities” (Broad, 1997, p. 2). Transfer is the primary objective of teaching, yet it is the most challenging goal to reach (McKeough et al., 1995; Foley and Kaiser, 2013; Furman and Sibthorp, 2013; Hung, 2013). Seminal authors stipulate that most of the time, the application of what is learned is “left to chance” (Caffarella, 2002, p. 209; Ford, 1994; Furman and Sibthorp, 2013). The fact that billions are spent each year on training, yet only 10% results in transfer of knowledge, skills, or behaviors in the work place or at home, illustrates the lack of focus that educators, facilitators, and trainers place on learning transfer (Ford, 1994; Awoniyi et al., 2002). Broad and Newstrom (1992) identified six key factors that can either hinder or promote learning transfer: (a) program participants, their motivation and dispositions and previous knowledge; (b) program design and execution including the strategies for learning transfer; (c) program content that is adapted to the needs of the learners; (d) changes required to apply learning, within the organization, complexity of change; (e) organizational context such as people, structure, and cultural milieu that can support or prevent transfer of learning values (Continuing Professional Development); and (f) societal, community forces. These factors are particularly important because some of the study’s findings concur with them, as elaborated further in the Section “Discussion.” Next, we describe the many factors limiting learning transfer.

Although it has been challenging for scholars to measure learning transfer and its impact to date, seminal authors, such as Caffarella (2002), Ford (1994), Hung (2013), Illeris (2009), Knowles (1980), Lightner et al. (2008), Taylor (2000), and Thomas (2007) have written extensively about what inhibits the transfer of learning. As Knowles (1975, 1980) recommended, adults need to understand when, where, and how they will be able to apply the knowledge they learn to their unique situations. Hung (2013) concurs with Knowles and argues that often the knowledge is not situated enough, and that adults are not able to make connections to their real-life situations. Thomas (2007) suggests that barriers to transfer can happen before, during, or after training. He classifies the barriers to learning transfer into three categories: the barriers related to the learner, the ones related to the situation, and those dealing with the facilitator.

Scholars have identified several barriers to learning that occur at the level of the learner. The learner may lack foundational knowledge or lack motivation (Knowles, 1980; Caffarella, 2002). Without foundational knowledge, the learner has insufficient experience or context to connect the new knowledge to past experiences and understand its potential relevance to future situations. Without motivation, the learner will likely not focus and retain what is important to his or her situation. Another learner-based barrier is that the educators in this part of the world are not accustomed to independent learning. In most developing countries, the teaching culture relies on a stand and deliver style, in which the facilitator talks and the learner listens. Yet research has shown that adults need to play an integral part in their own learning in order to transfer the knowledge to their settings (Knowles, 1975, 1980; Pratt, 1993; Mezirow, 2000).

The physical qualities of the environment where the learning is to take place make a difference. The room in which the training takes place might be inappropriate or uncomfortable. It may lack resources or equipment (Ford and Weissbein, 1997; Taylor, 2000; Merriam and Leahy, 2005). Taylor (2000) proposed that programmatic elements, such as the length of the training, the size of the class, and the time of day or night that the training is offered, can promote or inhibit learning transfer. Another hindrance to learning transfer could be the lack of follow-up after the training by the facilitator or other stakeholders (Caffarella, 2002) or a climate that does not foster trust (Knowles, 1980; Taylor, 2000). Caffarella (2002) also argues that unfavorable political climates will not permit learning transfer to take place.

Since learning is a process, not an event, learners ought to be included in the design of their learning experience (Knowles, 1975, 1980). Learners also need to be assessed, and the facilitators need to formulate goals and evaluate the process by being reflective (Knowles, 1980). Similarly, the shortage of opportunities for students to directly apply the new knowledge to context also prevents transfer. Illeris (2009) proposed that it is important to design learning activities for all types of learning and that some learners are visual learners while others are kinesthetic learners. Correspondingly, some learning takes place best through field activities, while others can be done in a classroom environment. Another problem with transfer is the issue of maintenance: how long can we expect the acquired knowledge to be maintained and what role can the facilitator play in making sure that the knowledge is maintained (Ford, 1994).

In a qualitative exploratory study of 11 workplace literacy instructors, students, and supervisors, Taylor (2000) examined the factors influencing learning transfer. The purpose of his study was to explore whether trainees were able to effectively apply new knowledge and skills gained from the literacy program to their jobs, and if so, how. Taylor believes that the transfer is dependent upon three people: the trainee, the facilitator, and the supervisor. This study showed that the trainees were not able to transfer, first because there was a lack of reinforcement to support the trainees in applying their new knowledge to their jobs. In addition, the environment was not favorable to transfer. Trainees reported a lack of equipment, they were too busy after the training to transfer the new knowledge, and they were not supported adequately with the transfer of learning.

This next section examines the factors that enhance learning transfer and is divided into three subsections: what the learners’ responsibilities are in fostering learning transfer, what the organization can do to promote learning transfer, and what role the facilitators play in facilitating transfer.

First, we examine the learner’s responsibilities in fostering learning transfer. Knowles’ (Knowles, 1980) model of andragogy outlines a few fundamental elements required for learning transfer. First, the learners need to be self-motivated. The learners also need to be willing to reflect, collaborate, and engage in conversations and disagreements. Mezirow (2000) further suggests that learners need to engage in transformative discourse in order to question their assumptions and gain new knowledge. To do that, learners need to be willing to learn differently and participate in learner centered pedagogies, including problem solving, case studies, and role-plays. In addition, there are five personality traits important for transfer: “consciousness, openness to experience, extraversion, emotional stability, and agreeableness” (Baldwin and Ford, 1988, p. 63). Learners ought to be open to collaborating, ready to reflect and interested, and ready to listen to and discuss other points of view.

In terms of the organization’s responsibilities, the location, time, and conditions of the training ought to be convenient and conducive to transfer. Organizing the logistics in advance is beneficial (Ford and Weissbein, 1997; Taylor, 2000; Merriam and Leahy, 2005). In particular, organizers or people in charge of the training should think about the ideal class size, the length of the training, the time of the day or night of the training, the date at which the training is offered, and whether the location is convenient to access (Curry et al., 1994). Moreover, the room where the training is held needs to be inviting and have sufficient equipment, light, and comfort to enhance transfer (Taylor, 2000). In addition, the tables inside the room need to be arranged according to the type of activity the facilitator chooses. The organizers should also build in post-training actions, finding additional time and resources soon after the training to allow facilitators to conduct follow-up trainings, host discussions, or create opportunities to re-connect with the learners to check on their progress. Lastly, organizers and facilitators need to assess the satisfaction of the trainees and use their feedback to inform future programming and facilitation improvements (Rachal, 2002).

Lastly, concerning the facilitator’s responsibilities, a good facilitator is skilled, passionate, eager, and enthusiastic, and is approachable and welcoming. He/she has a sense of humor, is interested in his or her students’ lives and goals and helps them reach them. A skilled facilitator observes what is spoken as well as what is unspoken (McGinty et al., 2013).

Open communication and teaching methods also play a role in learning transfer. An effective facilitator is aware of participants’ stressors that are due to the larger context, whether they are political, economic, health, or personal (McGinty et al., 2013). Another facilitator skill that promotes learning transfer is scaffolding, which refers to instructional methods that support students in their learning process (Ford and Weissbein, 1997). To scaffold the content, facilitators select content that is accessible to the learners so that they focus on the skill being taught. Scaffolding takes place through a safe learning environment, the set-up of the room, lighting, and ventilation (McGinty et al., 2013). Scaffolding also includes establishing an environment in which learners are emotionally safe. Such an environment includes speaking a common language, being inclusive, and being aware of socio-cultural differences in the room (Closson, 2013). Beyond an awareness of who is represented in the room socially and ethnically, Caffarella (2002) suggests that the content of the material should reflect the cultural differences in order to enable transfer. The author asserts that learning transfer is discussed within contexts, and hence context matters and affects the way we teach, what we teach, and how we teach (Rachal, 2002). Facilitators ought to utilize culturally responsive materials, be humble, and act with tact when working with minority populations in developing countries (Closson and Kaye, 2012). In these marginalized communities, the outsiders (i.e., those not from there) ought to use stories and songs of the nationals in order to be culturally respectful and responsive and to build trust and strengthen the bond between facilitators and learners over time (Silver, 2000). For example, case studies have been shown to be an effective technique for teaching adults (Macaulay and Cree, 1999) because they include context as an authentic part of the teaching and learning. Caffarella (2002) further posits that the content of the material must be balanced and learning transfer strategies used, such as individual learning plans, mentoring, follow-up sessions, support groups, networking, reflective practices, chat rooms, list serves, or portfolios.

Mezirow (2000) states that facilitators need to lead the trainees in purposeful reflection. This purposeful reflection is a key element in learning transfer, and is augmented when supplemented by diverse viewpoints and concept mapping to organize the knowledge. Additional scholars have identified this idea of reinforcing and practicing the new learning as crucial for transfer (Quinones et al., 1995; Seyler et al., 1998). Linked to the idea of revisiting new knowledge is the notion of feedback (Morgan et al., 1998). The authors argue that feedback from facilitators to trainees, and from trainees to trainees, is paramount to effective transfer and to successful group work, which is also believed to enhance transfer. In developing countries, feedback should be given to the learners at an early stage and authentic encouragement should be part of the andragogy to enhance learning transfer (Closson and Kaye, 2012). The collaboration can take several forms, one of which is that of learning communities (McGinty et al., 2013). The importance of collaboration and participation between the facilitator and the learners is emphasized in Lave and Wenger’s (Lave and Wenger, 1991) theory of situated cognition, which focuses on what they call legitimate peripheral participation (LPP). In LPP apprentices learn from experienced practitioners by first learning and practicing basic tasks. Through these activities, and with further collaboration with the experts, apprentices become familiar with their duties and better understand the community and its needs. LPP illustrates how collaboration is instrumental to learning and learning transfer and why facilitators need to employ this critical strategy.

Using the conceptual framework of learning transfer and the theory that underpins it, this study examined what enhanced and hindered learning after a professional development event. This concept could have a significant impact on schools in developing countries as school leaders play a pivotal role in the overall success of the schools and students learning outcomes. This paper is part of a larger study, which sought to explore how, if at all, proprietors and head teachers of LFPs are able to transfer to their schools the newly acquired knowledge after attending a 3-day leadership training in Burkina Faso and Ghana Brion, 2017. In this paper, we report the findings of the following research question: What enhanced and hindered the transfer of learning post professional development event to the LFPSs?

Materials and Methods

Selection of Research Sites and Participants

This qualitative exploratory study utilized a case study approach (Yin, 2014). Once we explored each case/school separately, we identified commonalities and differences within the six schools and made comparisons between the sites and the countries. The research sites were six LFPSs drawn from a 3-day-long school leadership training organized by an American NGO in collaboration with the University of San Diego. The training took place in July 2016. The participants were from Kumasi, a city from the Ashanti region, North West of Accra, the capital and Ouagadougou in Burkina Faso.

This research design relied on a purposive criterion and a convenience sampling of three proprietors and three head teachers of LFPSs. Purposive sampling allows researchers to select rich cases, from which one can learn the most and establish productive relationships that best enable answering the research questions of a study (Patton, 2002; Creswell, 2013). Criterion sampling was also used, as participants were chosen according to their ability to attend the 3-day school leadership training and to speak and understand the national language. Other criteria included the school’s size and number of years the school was in operation. The researchers selected schools with a minimum of 150 students and schools that had been in existence for at least 3 years because school leaders would be more inclined to focus on professional development once their schools were more established. This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of the University of San Diego’s Institutional Review Board with written informed consent from all subjects. The IRB was approved in March 2016.

Data Collection

Data collection included an initial informal meeting and in-depth interviews with proprietors and head teachers of LFPSs in two countries. Other data collection included site visits, and document review.

Data Sources

Initial Informal Meeting

Kvale and Brinkmann (2009) affirm that: “In a foreign culture, an interviewer needs time to establish familiarity with the new culture and learn some of the many verbal and non-verbal factors that may cause the interviewers in a foreign culture to go amiss” (p. 144). Spradley (1979) speaks about rapport as being “a harmonious relationship between ethnographer and informant” (p. 78). He refers to rapport as building trust with study participants in order to allow the information to flow freely. Building strong relationships based on trust is even more important in an international context when dealing with distinctive cultures and languages. Hence, the initial meetings served to build trust and rapport between the participants and the researcher. Both the school proprietors and the head teachers attended the initial meetings. During these meetings, the school leaders were also invited to read the consent forms for this study. All subjects gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. These preliminary meetings happened in July 2016 in the two countries studied.

Interviews

The in-depth interviews were the primary source of data for this study. Interviews included three proprietors and three head teachers for a total of six interviews in Burkina Faso and seven in Ghana. Interviews were semi-structured and open-ended and lasted 60–90 min. An interview guide was developed. We asked open-ended questions such as “Tell us about any changes that have happened in your school since the last training” or “Why did you make those changes? Can you give us an example of what was helpful to make the changes?” Interviews were audio taped and transcribed verbatim in French and English. The French transcriptions were not translated into English but rather coded in French. Ford and Weissbein (1997) posit that follow-up after a training should happen as soon as possible to avoid relapse; hence, the researchers conducted the in-depth interviews 3 months after the end of the training.

Site Visits

The purpose of the site visits was to corroborate the interview data. Post-training school visits took place at the same time as the in-depth interviews, 3 months after the school proprietors and head teachers had attended the 3-day school leadership training. Data collection included taking photographs as well as completion of matrices. This allowed comparison of matrices, which collected baseline data prior to the training and then post-training comparisons. The goal of utilizing these matrices was to discover if proprietors were able to implement aspects of their school improvement plans (SIPs), which they completed during the training. For example, Module 2 of the school leadership training dealt with health and wellness and emphasized the importance of having separate toilets for girls and boys. During the initial preliminary meeting and tour of the school, we took photographs and took notes to see if separate toilets existed. After the participants had the training, we reviewed the School’s Improvement Plan and looked for changes, if any, regarding toilet facilities. During these school visits, these researchers wrote field notes as well, which were later coded.

Document Review

Document analysis consisted of the goals in the SIPs and mission statement completed by the study participants during their trainings, as well as other artifacts, such as photographs and matrices. These documents were key to understanding if learning transfer occurred. In addition to providing a rich source of information to address the research questions, the document analysis functioned as a source for data triangulation.

Data Analysis

We looked at extracting convergences and recurring regularities within the three schools in each country. Content analysis included identifying, coding, categorizing, classifying, and labeling the primary patterns in the data. We coded all the transcripts by hand. Analysis of qualitative data took place over two cycles. In round one, open codes were developed for each key point emerging from the interviews, documents, analytical memos, field notes, and journal. In round two, codes were grouped into overlapping categories to create themes.

Trustworthiness

Triangulation was used with several different sources of data, such as the in-depth interviews, site visits and field notes, and the document analysis (Creswell, 2013). In addition, the researchers went back to the program officers in each country as well as the facilitators of the training in Ghana to ask them to check the accuracy of the findings, which can be referred to as a form of member checking (della Porta, 1992). Member checking was used to enhance the likelihood of credible findings (Lincoln and Guba, 1985).

Limitations

Conducting research internationally presents a certain number of challenges. First, due to financial constraints and the cost of leading research internationally, we stayed for a limited number of days in Ghana. This short duration prevented us from looking at the transfer of learning over several months in several West-African countries. In addition, we studied three LFPSs only, limiting my sample and transfer of the findings to other contexts.

Despite these limitations, this study contributes to the body of literature on learning transfer, particularly as it is a concept not been readily studied in Africa. This study helps set the stage for further interventions and possible cross-cultural collaborations.

Results

The research question sought to examine what enhanced and inhibited learning transfer after a professional development event in Burkina Faso and Ghana. Next, the findings from Burkina Faso are presented. To respect the participants’ ideas they are cited verbatim throughout the study. To respect their anonymity, pseudonyms for the school were used.

Burkina Faso

Inhibitors to Learning Transfer

Interviews with participants conveyed that there were several factors that inhibited the transfer of learning. First, all participants spoke about the financial challenge. All schools had received a loan and found it difficult to pay it back and improve their schools at the same time. One head teacher explained, “With the loan we must repay, it is hard to find additional money to make some changes in the school.” Related to finances, enrollment was an issue in one case. La Gloire School had an incoming sixth grade class of nine students, which prevented the leaders of the school from building the new toilets they intended to construct. In other cases, the lack of financial means prevented the school leaders from expanding, building additional classrooms, or buying land. The La Grace School owner said: “Once we have more funds, I am ready to expand and buy the land next door.” In one case, the lack of money made it impossible for the school to get electricity, which was “impeding getting quality teachers because they would want electricity to use the projector, make photocopies and so forth.”

Another inhibitor to transfer revealed in all six interviews was a challenge requiring human behavior change, referring to the challenges pertaining to changing the mindsets and habits of teachers and parents. Several school leaders mentioned that it was difficult to gain the trust of parents and to make them “realize that we are trying to do a good job.” One interviewee shared that “most of the parents are of Muslim faith and since I am running a Christian based institution, it caused frictions preventing the parents from trusting the team at school.” This leader went on by saying: “The parents that are Muslim are not trusting us easily.” Another leader stated that most of the parents at his school were illiterate, making it difficult to share with them what they had learned in the training: “They would not see or understand the value of what we are sharing with them and it would be difficult for them to make adjustments.” A third leader added: “It was hard to bring the teachers to share the same vision as us.”

A third inhibitor for all schools was the competition of nearby private or public schools. In all schools, there were competitors nearby that charged less than the schools studied. As a participant explained: “Sometimes the competition is illegal competition because those private schools are not registered with the government and the government asked them to close in some instances but they would not listen and to date they are still operating.” In one case, these competitors were believed to have practiced juju on the school. Juju is a West-African practice similar to witchcraft whereby animals or objects are used to hurt someone. Africans often fear the unseen spiritual world of juju, which includes curses, demons, and upsetting ancestors. In this study, one school reported having been the victim of juju. The proprietress of Wendkuuni School shared:

One morning we arrived at school and there was a large pile of trash in the middle of the school yard. The guard wanted to move it away so our yard was clean to receive the students. Next thing we know the guard’s foot was infected and all bloody. We went to the hospital but they told us that was not something medical doctors could fix. They said it came from somewhere else, you know, and they could not do anything for it. The guard almost lost the use of his foot. We care for him so I visit him every day and I help him with feeding and medical care. But because of this event, we also lost some students, you see, they went somewhere else.

To summarize, in Burkina Faso, inhibitors to the transfer of learning were financial, related to the need to change human behavior, and associated with competing school(s), which (a) took students from the schools involved in this study and (b) practiced juju. Another inhibitor linked to the lack of finances concerned the recruitment of quality teachers because the proprietors/head teachers reported that trained teachers asked for costly materials, such as overhead projectors. All participants mentioned having financial and human difficulties as well as too many lawful or unlawful competitors. The next section addresses what enhanced the learning transfer to the school sites.

Enhancers of Learning Transfer

All six participants in Burkina Faso mentioned that the Participant Guide that was given to the participants during the training was “helpful” and “made it easy for us.” They stated that the content was appropriate for their context and that it was “clear and well done.” One leader said, “You people hit all the points we need in the Guide.” All interviewees are still using the guide to either train others on it, or hold meetings with parents. All interviewees also commented on the andragogy used during the training and in the Participant Guide. In Burkina Faso, the andragogy used is mostly one of stand and deliver where the facilitator speaks the entire time and the participants write and listen. For the leadership training, an active andragogy was used whereby trainees would create their own knowledge by working in pairs, in tables, having time carved out to reflect, engage in a case study, and write their SIP at the end of each day. One school leader stated:

The case study helped me to build my confidence and to identify with it. I came back to my school and started to hire younger people because in the case study where we had to recruit teachers, I chose to hire a younger teacher despite the fact that everyone else in the group chose the old man who used the cane!

Others shared that they appreciated the “give and receive approach.” And all commented, “We learned a great deal from each other and continue to do so by keeping in touch with each other by phone, or when time permits visiting each other school.” One head teacher put it in these terms: “I liked the atmosphere and liked engaging with others in a relaxed way.”

Related to the Participant Guide, all interviewees commented on the qualities and dispositions of the facilitator. They shared that the facilitator “was willing,” “attentive,” “she touched us and made us comfortable.” One other person affirmed that she knew her content and was passionate. One proprietress added: “I memorized her words.” A head teacher affirmed: “She made us feel like family, so we could share.”

All leaders also commented on the hotel facility as being comfortable and conducive to learning. All mentioned the meals they were served each day. “When we left in the morning to come, we did not eat but we arrived at the hotel and we were fed allowing us to focus on learning.” One proprietor added: “I passed by this hotel but I always thought it was reserved for the big people, I liked it and we ate well.”

Moreover, one participant indicated that having a head teacher present at the training was facilitating transfer since “he is the person that is in charge of making things happen at school.” Three other persons affirmed that having someone from previous cohorts come and give testimonials was helpful; “it allowed us to concretely see how to put into practice the theory we learned.” All participants made reference of the certificate of completion that they received at the end of the training. They claimed the certificate gave them the confidence to improve their schools; one person affirmed, “You see now I have the certificate, that means I know something and need to show the others how to do it.” Similarly, one school had posted in their school office the group picture taken during the training and the leaders said: “We refer to it to give us courage and also to show teachers and parents.”

In one instance only, a school leader spoke about two other kinds of transfer enhancers. She spoke of her husband helping her to build an additional classroom and of the micro-lender who lent her additional funds despite the fact that she already had one loan. She said: “Since you first came, my husband built a new classroom for me and I went to the micro-lender to ask for more money because I wanted to make some changes that cost.”

Burkinabe participants offered that what helped them transfer the learning to their schools was the Participant Guide, the andragogy used to facilitate the training, the quality of the facilitation, the facilities in which the training was held, the certificate, and the group picture given at the outset of the training, as well as the testimonials from previous cohort members. One trainee also mentioned that having the leadership of the school attend the training was helpful to transferring knowledge. Other transfer of learning enhancers included support from family and from the micro-lender.

Ghana

Inhibitors to Learning Transfer

Study participants cited several inhibitors preventing them from transferring the new knowledge to their schools. The first inhibitor was financial, having to repay a loan while charging low tuition. “The challenge is we have to pay every month the loan, but we are committed to do that to be able to get a second loan to do something significant.” One participant even shared that having a more balanced diet at school for the children is costly for the school: “We often run the food part of the school at a loss and sometimes the proprietress has to put in her own money to cover it.”

Furthermore, participants stipulated that they met complications pertaining to people’s (or staff’s) behavior. Specifically, leaders talked about teachers as being reluctant to adapt to higher expectations and lady cooks resisting wearing a cap. “It was hard for the cooks at first to re-adjust to new rules, and wear their caps.” One younger leader spoke of the human behavior problem in different terms saying that he “felt intimidated sometimes bringing up ideas to his superiors because they were far older” than he was and “culturally that was a challenge.” This young leader referred to the power issues and dynamics inherent in Ghanaian culture. Related to both the financial and human challenges, all participants spoke indirectly about the competition they were facing, stating that “if we raise our tuitions, parents will leave the school and go next door.”

Another inhibitor to learning transfer had to do with what a participant called “not knowing what you do not know.” One proprietor explained that fencing his school had a significant impact on the parents. They were happy and congratulated the school for taking such a safety measure.

However, it was much harder to get recognized when we taught the parents about the food pyramid. You see the fence parents can see and measure its impact, the food they cannot see the results immediately and since they are not educated, they did not know what we taught them and if they had not come to the meeting, they would not have known what they were missing out.

The proprietor continued:

If a proprietor has the choice between making a change that is visible and informing on nutrition that people have no idea on, they would choose the visible change for marketing purposes … that in itself creates a challenge because they choose what to transfer according to the impact it will have most on the finances of the school.

This leader spoke about the choices other leaders make regarding what knowledge to transfer to the schools and which ones would be most immediately visible and financially beneficial on the short term.

The last challenge that was brought up was of a logistical nature. When the training took place in Ghana in early July, the schools were still in session, making it challenging for the leaders of the school to transfer later. One head teacher said: “It would be better during the vacation because our minds are more free.”

Similar to Burkina Faso, all Ghanaian school leaders faced financial and human behavior issues. Unlike Burkina Faso, leaders in one school also mentioned the timing of the training as an issue. They felt that trainings should be offered during the holidays to allow for better transfer. Another finding was the fact that people tend to transfer new knowledge when it is visible to the customers and can immediately have an impact on income. The knowledge that people do not know may be less important since people do not know what they do not know; not realizing the value of the new knowledge at first, hence discouraging leaders to transfer some of the new knowledge. Besides the challenges, proprietors and head teachers also mentioned multiple factors that assisted them in transferring the learning to their institutions.

Enhancers of Learning Transfer

Participants praised the content of the training modules. According to them, the modules were adequate for their context. One leader said: “The reality was there for us in the books” and “made us realize what we do not have.” They appreciated the activities, the reflection questions that “forced us to think,” the homework and the SIP. The SIP was “a gateway for us, allowing us to see where we should go next.” Another leader added: “The SIP helped us to stick to what we told you we would do.” All enjoyed the andragogy used and appreciated networking and working with every participant throughout the training. “We learned a lot from each other and heard what other[s] did or what problems they had.” They all commented on the “good atmosphere” during the training. In addition, everyone noted that the facilitators were competent and “knew where to touch.” Finally, everyone enjoyed the hotel facility and the service and the food. One leader described the training facilities in these terms: “The service, the food were good and all for free.”

All three schools in Ghana transferred some learning to their institutions from the July training. Two schools were able to put into action far more than the third one. All schools faced multiple challenges. All confronted financial inhibitors and human challenges. All schools appreciated the training materials, the facilitators, and the andragogy used. They all enjoyed the facility and the daily meals.

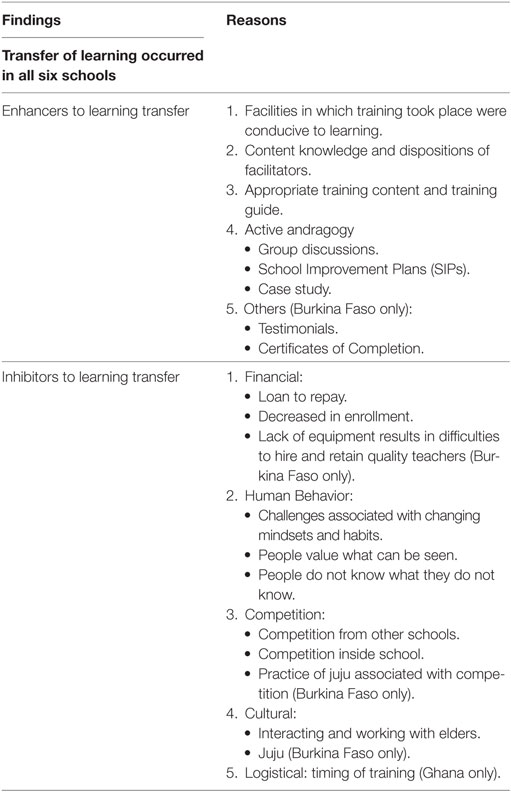

The findings of this study indicate that learning transfer occurred in all three schools in Burkina Faso and all three schools in Ghana. Table 1 summarizes the factors that enhanced and inhibited the transfer of learning in Burkina Faso and Ghana. As Table 1 shows, factors that supported the transfer of learning in both countries included the location and logistics of the training, the facilitator’s content knowledge and disposition, the adequate content of the training, the active andragogy used, as well as testimonials given by other cohort members. In Burkina Faso, the certificate of completion presented to all participants at the end of the 3-day training as well as the testimonials given by an alumnus seemed to have supported the transfer of learning as well. When given a certificate of completion and hearing testimonials, participants perceived that they were more competent, felt confident, and were motivated to transfer the new learning to their schools. The findings also revealed key challenges to learning transfer. The inhibitors in both countries were not only financial but also associated with (a) human behavior, (b) competition, and (c) culture. Leaders from one school in Ghana referred to the scheduling of the training as being an issue as the training took place while the school was still in session.

Discussion

Inhibitors to Learning Transfer

Scholars have written extensively about what inhibits the transfer of learning (Broad and Newstrom, 1992; Ford, 1994; Caffarella, 2002). According to Broad and Newstrom (1992), inhibiters to learning transfer may come from (a) the program participants themselves if they lack motivation and prior knowledge; (b) the training material and its content; (c) the follow-up; and (d) the external cultural and social contexts. The following section presents the findings that concur with the current literature on learning transfer as well as the findings that are new contributions to the existing body of literature.

Transfer That Is Visible to Others Is More Valued

In this study, all 13 school leaders from both Burkina Faso and Ghana were able to transfer some learning after the 3-day leadership training. Although there was evidence of transfer related to all aspects of the four modules studied, much of the visible transfer was related to improving the building facilities. Painting a building, buying new chairs and hand washing stations, or labeling classrooms only require knowledge, money, and time. Heifetz (1994) refers to these as solutions to technical problems, as they can be fixed with expertise and good management. The school leaders learned in the training that beauty was linked to improved student outcomes, they learned that signage increased the visibility of their schools, so they made those changes in order to attract more parents and students. One of the leaders from Akwaaba School in Ghana understood and spoke about the urge to transfer first and foremost the knowledge that produces visible changes because customers understand and are attracted to changes that they can see immediately. He explained that other changes that require a behavior or mindset change, what Heifetz would refer to as adaptive work, are far more difficult to tackle because they involve changes that do not usually yield additional customers in the short term. School leaders in this study were mostly interested in making short-term changes, because they had loans to repay and often lived modestly themselves. In providing this example, this school proprietor was explaining the difference in mindsets and priorities in Ghana and the importance of understanding those variances when examining the learners’ abilities to transfer new knowledge to their schools. This finding supports Broad and Newstrom (1992), who denote the cultural and social contexts as possible inhibiters to learning transfer. Related to the idea of transferring first what is visible, is the idea that people cannot transfer or teach to others what they do not know themselves.

People Do Not Know What They Do Not Know

As the subheading statement made by a participant indicates, another barrier to the transfer of learning that all participants noted was related to human behaviors. All participants mentioned the difficulties they had in transferring new knowledge when it involved changing mindsets, changing habits, or setting higher expectations for their staff, teachers, and parents. This human behavior challenge also explains why transferring what is visible first was preferred. Broad and Newstrom (1992) and Knowles (1975) addressed the lack of prior knowledge as a barrier to the transfer of learning. Caffarella (2002), as well, discussed the necessity for trainers and facilitators to be culturally sensitive and to understand the local norms, traditions, and cultures in order to facilitate the transfer of learning. This was found to be the case in both Burkina Faso and Ghana. Also, in both countries, the idea of changing mindsets and habits was an additional challenge to transferring knowledge, particularly when it came to changing eating habits. This is explained by the fact that (a) people are not aware of what a balanced meal is and why it is needed (lack of knowledge); (b) people cannot afford eating a balanced diet (financial issue); and (c) people eat what they grew up eating, what they perceive as being healthy foods and necessary to eat (mindset and habit). People eat food to feel full, preferably food that will fill their stomachs for long periods of time and foods to which they have a cultural and emotional connection. Many participants joked and said that if they ate a balanced meal but did not eat fufu at each meal, they felt like they “did not eat anything.” Fufu is a staple food in West Africa and is made out of cassava and green plantain. One participant further explained:

You see, I understand what you are telling us about eating a balanced diet, but here in this region of Ghana, unless you eat fufu, it feels like you have not eaten. For me, I grew up eating fufu. In other regions, people eat rice or banku but for my tribe it was fufu.

This study showed that mindsets are particularly challenging to alter. Broad and Newstrom (1992) speak about the complexity of making changes within an organization. Changing mindsets is a complex task and requires leadership. Adaptive leadership is necessary in African schools to alter deeply rooted beliefs and transform mindsets. Adaptive work involves a disparity between values and circumstances and the role of the leaders is to close that gap. In order to close the gap between values and circumstances, leaders need to be trained and acquire the skills and knowledge necessary to undertake this difficult task. In addition, to tackle adaptive challenges (i.e., the ill-defined problems), leaders need to know their competition (Heifetz, 1994).

Knowing the Competition

Another barrier to transfer mentioned in all schools was competition from other schools. In this study, all schools were surrounded by other public or private schools and found it challenging for several reasons. For example, competitors would attract away students from schools in this study creating a decrease in enrollment for La Gloire School in Burkina Faso. This decrease in enrollment meant a heavier financial burden for La Gloire and the inability to transfer much knowledge due to a lack of financial support.

In one case in Burkina, competitors sometimes would practice juju on the school. That school reported having been the victim of this witchcraft practice. By putting into danger, the life of a school employee, the school leaders incurred added costs to temporarily replace the injured employee and to care for him. In addition, the institution lost some students to the competing schools during this period because people learned about the juju spell that was cast against the school.

School leaders ought to know their competition in order to understand their school’s value proposition. For example, leaders ought to seek to understand why they have empty seats in their schools. They also ought to comprehend who and where their competition is so as to set their school tuitions accordingly. Finally, leaders ought to manage the internal and external conflicts that are resulting from the competition in order to improve their schools.

In another instance, the “competition” was not coming from other schools but from within the school. In Nyame school, the competitors were the two senior school leaders who were older than the Director of Academics. In this case, the younger leader spoke about the challenge of sharing new ideas with his leaders because they were elderly. He shared that, because of the top-down leadership, “it is culturally inappropriate when a younger person brings new ideas.” Hence, he viewed his leaders as competing against him. The last significant barrier to learning transfer that emerged from the findings was the lack of capital.

Finance Matters

All participants noted that lack of funds prevented them from implementing more changes in their schools after the training. All school leaders interviewed had a loan to repay and found it challenging to transfer new knowledge to their schools because many of the changes needed involved some level of investment. Finances as a barrier to learning transfer is largely absent from the literature because western scholars wrote the literature on adult learning transfer based on western organizations. In this study, leaders of LFPSs in these two developing countries shared their daily struggle to serve families with limited financial means while wanting to provide a quality education in an improved environment.

Enhancers of Learning Transfer

Knowles (1980) outlined a few fundamental elements required for learning transfer to occur. First, the learners need to be self-motivated. The learners also need to be willing to reflect, collaborate, and engage in conversations and disagreements. Mezirow (2000) further suggests that learners need to engage in transformative discourse in order to question their assumptions and gain new knowledge. To do that, learners need to be willing to learn differently and participate in learner-centered pedagogies, including problem solving, case studies, and role-plays. Learners ought to be open to collaborating, ready to reflect, and interested and ready to listen to and discuss other points of view. According to Broad and Newstrom (1992), there are other elements that enhance learning transfer such as the organization of the training, including the length, time, and location. The authors further affirm that the facilitation (andragogy and training activities), the quality of the facilitators, the adequacy of the training materials, and the changes required to apply learning within the organization are also essential to enhance learning transfer.

Facilitators and Facilitation

As far as what enhanced learning transfer in Burkina Faso and Ghana, participants mentioned the quality and dispositions of the facilitators. The facilitators were knowledgeable, approachable, fostered a climate of trust, and used varied pedagogies that allowed for group work and reflection. These findings are in agreement with Mezirow (2000). Facilitators also understood the local context and were aware of the struggles that school leaders faced. These findings concur with the current literature on learning transfer (Broad and Newstrom, 1992; Closson, 2013; McGinty et al., 2013). Participants also appreciated the positive feedback, the encouragement, and the collaboration among participants and between participants and facilitators, which supports Lave and Wenger’s (Lave and Wenger, 1991) theory of situated cognition whereby learners progressively become experts as they collaborate with the professionals. In addition, the interviewees spoke highly of the student-centered teaching strategies used, such as the case study, and the SIP at the end of each day. Those findings are supported by the literature and are applicable to the developing countries studied (Ford, 1994; McGinty et al., 2013).

Facilities

All participants appreciated the facilities in which the training was offered. They stated that it “was conducive for learning” and “the foods that was served during the morning snack and mid-day lunch were delicious and all for free.” Authors such as Ford and Weissbein (1997) as well as Merriam and Leahy (2005) and Taylor (2000) speak about the importance of the conditions for learning. The findings of this study concur with the transfer of learning literature when it comes to the environment as being key to learning and to the transfer of knowledge. Two elements surfaced in this study that have not yet been addressed in the literature on adult learning transfer. Data demonstrated that the awarding of a certificate of completion and the testimonials given from alumni encouraged participants to transfer the new learning to their schools.

Certificate of Completion and Testimonials

Six participants made mention of the certificate of completion they received as being significant for them to transfer knowledge. The certificate gave the participants pride and confidence that they were able to transfer the new knowledge. The certificates may be essential in emerging countries because many adults do not have access to a formal education or do not have the opportunity to attend trainings. Leadership trainings in Africa are rare for both public and private school leaders, but especially for LFPS’s leaders. Hence, the certificate may not only have a symbolic value to the leaders but it may also provide them with a certain status. The leaders who did not overtly speak of the certificate had it posted in their office.

The other element that emerged from this study, and that is absent in the literature on learning transfer, is the use of testimonials. Half of the school leaders insisted that having school proprietors and head teachers who received the training prior to them come to share with them how they used the training in their schools was helpful. These testimonials allowed the trainees to ask questions and see concretely how to apply the knowledge and hear about the benefits the changes yielded for those from previous cohorts. Only half of the sample spoke about this because only the participants in Burkina Faso had an alumnus from the training come to have lunch with them. Thus far, it is not a practice that has been adopted by the facilitators in Ghana. Such findings suggest that testimonials are important in these contexts and the practice of inviting alumni to trainings could be adopted in other countries if appropriate. Few Burkinabe participants shared that they visited the alumni’s school.

Conclusion

This study aimed to examine if, and how, proprietors and head teachers of LFPSs were able to transfer newly acquired knowledge to their school sites after having participated in a 3-day leadership training in Burkina Faso and Ghana, West Africa. The narrative of school leaders helped increase our understanding of this phenomenon. The first major finding was that trainees were transferring more elements that were visible to their customers because those visible changes do not require a behavior change and, hence, are easier to implement. The second finding revealed was the resistance to change when it came to altering mindsets and deeply rooted traditions and cultural factors. According to participants, another challenge that limited transfer was competition coming from either inside or outside the institution. Findings also suggested that what promoted learning transfer were quality facilitators, active learning and teaching strategies, adequate materials and facilities, as well as testimonials and certificate of completion.

Recommendations

Based on the findings and conclusions of this exploratory study, we offer recommendations for (a) practitioners; (b) NGOs, governments, and policy makers; and (c) future research.

Recommendations for Practitioners

Based on the findings, practitioners and consultants who prepare materials for developing countries ought to prepare those materials based on the local needs, not based on their Western ideas of what is needed. Being in the field, interviewing stakeholders, visiting sites, and having evidence-based materials are essential. Reflecting on the materials and modifying them based on the trainees’ feedback is not just crucial but a sound practice based on adult learning and learning transfer theories (Mezirow, 2000; Caffarella, 2002). Development expert Ruxin (2013) talks about the importance of working “in the mud.” By this, he means it is crucial to be with people on the ground to create materials that locals need, allowing them to transfer the new knowledge to their work place and hence have a sustainable influence. This practice avoids aid colonialism whereby Westerners have started development initiatives only to find out that when they left, the efforts stopped and—even worse—divided the communities, just like the colonizers did. Being in the mud also allows for better understanding of the local cultures, power dynamics, and belief systems. In this study, the material used during the training was piloted, modified, and contextualized based on hundreds of interviews with the local school leaders and with local trainers, scholars, and leadership experts.

Second, because of the lack of leadership training offerings in both Burkina Faso and Ghana, there is a need for additional culturally responsive leadership modules that address leadership principles, such as tackling adaptive challenges and building a trusting team. School leaders ought to also be trained on assessing their competition, doing market studies, and how to have productive healthy relationships with their competitors. In addition, more training modules or workshops ought to be developed on topics such as how to set tuition fees and marketing.

Based on the findings, for trainings in emerging nations, trainers, consultants, and facilitators should consider having trainees from previous cohorts come to give testimonials to the newly trained cohort. Successful alumni of the trainings could become group moderators for the mobile technology follow-up intervention.

Lastly, for anyone who works with adults anywhere in the world teaching or facilitating trainings and/or meetings, it would be beneficial to understand the key concepts of learning transfer, as well as the adult learning theories used as conceptual framework in this study.

Recommendations for NGOs, Governments, and Policy Makers

Because of the Millennium Development Goals and now the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), $2.3 trillion has been spent on foreign aid in the last 60 years (Myers, 2011). To ensure that investments made do not turn into dead investments, and that development initiatives are sustainable once the Westerners leave, the following recommendations are aimed at all funders and supporters of development initiatives.

For NGOs that organize trainings, it is advisable that the trainings are offered at the best possible time for the intended participants. In addition, it is essential that trainings be held in quality facilities with adequate learning conditions, as seen in the learning transfer literature. Furthermore, given the impact the certificates had on the trainees’ confidence, status, self-worth, and on the transfer of learning, it would be important to give each participant a certificate.

Finally, for policymakers, governments, and anyone in charge of organizing trainings, workshops, or gatherings, getting familiar with the learning transfer and adult learning literature is recommended. Without understanding how adults learn and how best to enhance learning transfer, there will be little return on investment. For an effective use of time and money and to develop sustainable programs, it is essential that trainers and curriculum designers understand adult learners, their needs, their cultural context, and how to help them be successful in transferring the new knowledge. It is only possible to meet the Sustainable Development Goals of achieving quality education for all and achieving gender equality and empowering all women and girls if monies are invested properly and trainings are led effectively with learning transfer in mind.

Recommendations for Future Research

Other longitudinal studies should examine how to enhance learning transfer and avoid relapse over longer periods of time. In addition, with a larger sample, cross-comparative studies should be conducted in both Burkina Faso and Ghana. Using change theories as theoretical framework, additional studies could examine the role culture plays in facilitating change.

Ethics Statement

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of the University of San Diego’s Institutional Review Board with written informed consent from all subjects. The study and the protocol were reviewed and approved by the University of San Diego’s IRB in March 2016.

Author Contributions

CB collected the data, designed the study, completed the analysis, and wrote the first drafts. She made final approval of this version. She agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work, including ensuring that questions related to the accuracy and integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. PC assisted with the design of the study and read several drafts providing feedback. She has reviewed this final version.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank the US-based NGO for providing logistical support for this research and the study participants for their time and trust. This article is part of a larger research project investigated in an unpublished dissertation, Low-fee Private Schools in West Africa: Case studies from Burkina Faso and Ghana, by one of the authors. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

Awoniyi, E. A., Griego, O. V., and Morgan, G. A. (2002). Person-environment fit and transfer of training. Int. J. Train. Dev. 6, 25–35. doi: 10.1111/1468-2419.00147

Baldwin, T. T., and Ford, J. K. (1988). Transfer of training: a review and directions for future research. Personnel Psychology 41, 63–105. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.1988.tb00632.x

Brion, C. (2017). Low-Fee Private Schools in West Africa: Case studies from Burkina Faso and Ghana. Ph.D. thesis, University of San Diego, San Diego, California.

Broad, M. L. (1997). Transferring Learning in the Workplace: Seventeen Case Studies from the Real World of Training, Vol. 5. Alexandria, VA: American Society for Training and Development.

Broad, M. L., and Newstrom, J. W. (1992). Transfer of Training: Action-Packed Strategies to Ensure High Payoff from Training Investments. Boston, MA: Da Capo Press.

Bush, T., Kiggundu, E., and Moorosi, P. (2011). Preparing new principals in South Africa: The ACE: School leadership program. S. Afr. J. Educ. 31, 31–43. doi:10.15700/saje.v31n1a356

Bush, T., and Oduro, G. (2006). New principals in Africa: preparation, induction and practice. J. Educ. Adm. 44, 359–375. doi:10.1108/09578230610676587

Caffarella, R. S. (2002). Planning Programs for Adult Learners: A Practical Guide for Educators, Trainers, and Staff Developers. The Jossey-Bass Higher and Adult Education Series. Indianapolis, IN: Jossey-Bass.

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). (2016). Factbook, 2016. Available at: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/uv.html

Closson, R. B. (2013). Racial and cultural factors and learning transfer. New Dir. Adult Contin. Educ. 137, 61–69. doi:10.1002/ace.20045

Closson, R. B., and Kaye, S. B. (2012). Learning by doing: preparation of Bahá í nonformal tutors. New Dir. Adult Contin. Educ. 2012, 45–57. doi:10.1002/ace.20006

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Traditions. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Curry, D., Caplan, P., and Knuppel, J. (1994). Transfer of training and adult learning. J. Contin. Soc. Work Educ. 6, 8–14.

della Porta, D. (1992). “Life histories in the analysis of social movement activists,” in Studying Collective Action, Sage Modern Politics Series, Vol. 30, eds M. Diani and R. Eyerman (London, England: SAGE), 168–193.

Fleishman, E. A. (1987). “Foreword,” in Transfer of learning: Contemporary Research and Applications, eds S. M. Cormier and J. D. Hagman (San Diego, CA: Academic Press), xi–xvii.

Foley, J. M., and Kaiser, L. M. R. (2013). Learning transfer and its intentionality in adult and continuing education. New Dir. Adult Contin. Educ. 2013, 5–15. doi:10.1002/ace.20040

Ford, J. K. (1994). Defining transfer of learning: the meaning is in the answers. Adult Learn. 5, 22–30. doi:10.1177/104515959400500412

Ford, J. K., and Weissbein, D. A. (1997). Transfer of training: An updated review and analysis. Perform. Improv. Quart. 10, 22–41.

Furman, N., and Sibthorp, J. (2013). Leveraging experiential learning techniques for transfer. New Dir. Adult Contin. Educ. 2013, 17–26. doi:10.1002/ace.20041

Grissom, J. A., and Harrington, J. R. (2010). Investing in administrator efficacy: an examination of professional development as a tool for enhancing principal effectiveness. Am. J. Educ. 116, 583–612. doi:10.1086/653631

Heifetz, R. A. (1994). Leadership without Easy Answers, Vol. 465. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press.

Hung, W. (2013). Problem-based learning: a learning environment for enhancing learning transfer. New Dir. Adult Contin. Educ. 137, 27–38. doi:10.1002/ace.20042

Illeris, K. (2009). Transfer of learning in the learning society: how can the barriers between different learning spaces be surmounted, and how can the gap between learning inside and outside schools be bridged? Int. J. Lifelong Educ. 28, 137–148. doi:10.1080/02601370902756986

Knowles, M. (1980). My farewell address … Andragogy no panacea, no ideology. Train. Dev. J. 34, 48–50.

Kvale, S., and Brinkmann, S. (2009). Interviews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE.

Lave, J., and Wenger, E. (1991). Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Leithwood, K., Louis, K. S., Anderson, S., and Wahlstrom, K. (2004). How Leadership Influences Student Learning: Review of Research. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, Center for Applied Research and Educational Improvement.

Lightner, R., Benander, R., and Kramer, E. F. (2008). Faculty and student attitudes about transfer of learning. Insight: J. Schol. Teach. 3, 58–66.

Macaulay, C., and Cree, V. (1999). Transfer of learning: concept and process. Board Soc. Work Educ. 18, 183–194. doi:10.1080/02615479911220181

McGinty, J., Radin, J., and Kaminski, K. (2013). Brain-friendly teaching supports learning transfer. New Dir. Adult Contin. Educ. 137, 49–59. doi:10.1002/ace.20044

McKeough, A., Lupart, J. L., and Marini, A. (1995). Teaching for Transfer: Fostering Generalization in Learning. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Merriam, S. B., and Leahy, B. (2005). Learning transfer: a review of the research in adult education and training. PAACE J. Lifelong Learn. 14, 1–24.

Mezirow, J. (2000). Learning as Transformation: Critical Perspectives on a Theory in Progress. The Jossey-Bass Higher and Adult Education Series. Indianapolis, IN: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Morgan, R. R., Ponticell, J. A., and Gordon, E. E. (1998). Enhancing Learning in Training and Adult Education. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood Publishing Group.

Myers, B. L. (2011). Walking with the Poor: Principles and Practices of Transformational Development. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books.

Pratt, D. D. (1993). Andragogy after twenty-five years. New Dir. Adult Contin. Educ. 57, 15–23. doi:10.1002/ace.36719935704

Quinones, M. A., Ford, J. K., Sego, D. J., and Smith, E. M. (1995). The effects of individual and transfer environment characteristics on the opportunity to perform trained tasks. Train. Res. J. 1, 29–49.

Rachal, J. (2002). Andragogy’s detectives: a critique of the present and a proposal for the future. Adult Educ. Q. 52, 210–227. doi:10.1177/0741713602052003004

Ruxin, J. (2013). A Thousand Hills to Heaven: Love, Hope, and a Restaurant in Rwanda. New York, NY: Little, Brown.

Seyler, D. L., Holton, E. F. III, Bates, R. A., Burnett, M. F., and Carvalho, M. A. (1998). Factors affecting motivation to transfer training. Int. J. Train. Dev. 2, 16–16. doi:10.1111/1468-2419.00031

Silver, D. (2000). Songs and storytelling: bringing health messages to life in Uganda. Educ. Health 14, 51–60. doi:10.1080/13576280010015362

Swaffield, S., Jull, S., and Ampah-Mensah, A. (2013). Using mobile phone texting to support the capacity of school leaders in Ghana to practise leadership for learning. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 103, 1295–1302. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.10.459

Taylor, M. C. (2000). Transfer of learning in workplace literacy programs. Adult Basic Educ. 10, 3–20.

Thomas, E. (2007). Thoughtful planning fosters learning transfer. Adult Learn. 18, 4–9. doi:10.1177/104515950701800301

United Nations. (2016). Sustainable Development Goals. Available at: http://un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). (2015). Education for all 2000-2015: Achievements and Challenges (EFA Global Monitoring Report). Paris, France: UNESCO.

Keywords: learning transfer, school leadership, developing country, low-fee private schools, professional development, education, sub-Saharan education

Citation: Brion C and Cordeiro PA (2018) Learning Transfer: The Missing Link to Learning among School Leaders in Burkina Faso and Ghana. Front. Educ. 2:69. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2017.00069

Received: 24 September 2017; Accepted: 18 December 2017;

Published: 08 January 2018

Edited by:

Monica Byrne-Jimenez, Indiana University Bloomington, United StatesReviewed by:

Katherine Cumings Mansfield, Virginia Commonwealth University, United StatesMarsha E. Modeste, Pennsylvania State University, United States

Copyright: © 2018 Brion and Cordeiro. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Corinne Brion, brioncorinne@yahoo.fr, corinnebrion@sandiego.edu

Corinne Brion

Corinne Brion Paula A. Cordeiro

Paula A. Cordeiro