Factors and Recommendations to Support Students’ Enjoyment of Online Learning With Fun: A Mixed Method Study During COVID-19

- Rumpus Research Group, Faculty of Wellbeing, Education and Language Studies, The Open University, Milton Keynes, United Kingdom

Understanding components that influence students’ enjoyment of distance higher education is increasingly important to enhance academic performance and retention. Although there is a growing body of research about students’ engagement with online learning, a research gap exists concerning whether fun affect students’ enjoyment. A contributing factor to this situation is that the meaning of fun in learning is unclear, and its possible role is controversial. This research is original in examining students’ views about fun and online learning, and influential components and connections. This study investigated the beliefs and attitudes of a sample of 551 distance education students including pre-services and in-service teachers, consultants and education professionals using a mixed-method approach. Quantitative and Qualitative data were generated through a self-reflective instrument during the COVID-19 pandemic. The findings revealed that 88.77% of participants valued fun in online learning; linked to well-being, motivation and performance. However, 16.66% mentioned that fun within online learning could take the focus off their studies and result in distraction or loss of time. Principal component analysis revealed three groups of students who found (1) fun relevant in socio-constructivist learning (2) no fun in traditional transmissive learning and (3) disturbing fun in constructivist learning. This study also provides key recommendations extracted from participants’ views supported by consensual review for course teams, teaching staff and students to enhance online learning experiences with enjoyment and fun.

Introduction

Online learning has been considered vital in 21st century to provide flexible education for students as well to address the gap between demand for higher education and supply. Governments have advocated increasing rates of completion of secondary and higher education in the face of rapid population growth. However, they face financial pressure to support these larger numbers directly through additional infrastructure, in addition to scholarships and student loans (Cooperman, 2014:1).

In recent years, there has been an increasing interest in distance online learning not only to educate students who work but also who live too remotely or cannot access traditional campus universities for other reasons. However, literature shows that online distant education has dropout rates higher than traditional universities (Xavier and Meneses, 2020). Studies also suggest that the students’ level of satisfaction about their online learning and own academic performance have significant correlation with their level of persistence toward completion (Gortan and Jereb, 2007; Higher Education Academy (HEA), 2015).

Understanding components that influence students’ enjoyment in distance higher education is fundamental to promote student retention and success (Higher Education Academy (HEA), 2015) during and post COVID-19 pandemic. There is a growing body of research about students’ engagement in virtual learning environments (Arnone et al., 2011). However, there are key issues that whilst extensively researched in traditional teaching, remain relatively absent from research into distance education. For example, a long established body of research exists that demonstrates a link between students’ epistemological beliefs and their study, engagement, and outcomes (Rodriguez and Cano, 2007; Richardson, 2013). The types of epistemological beliefs typically examined fall into two broad categories. The first is derived from Schommer’s research (Schommer, 1990), in which she elicited dimensions that reflected students differing beliefs. This included “simple knowledge” (knowledge as isolated facts vs. knowledge as integrated conceptions) and “innate ability” (ability to learn is genetically determined vs. the ability to learn is enhanced through experience). The second category of research is more directly aligned with pedagogy. This has positioned epistemological beliefs in relation to traditional or constructivist beliefs. Traditional views of learning see learning occurring via the non-problematic transfer of untransformed knowledge from expert to student (Chan and Elliott, 2004). This contrasts with constructivist beliefs in which knowledge arises through reasoning, which is facilitated by teaching (Lee et al., 2013). This type of framing can be seen in large scale international comparative research, such as the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development’s survey of teachers’ epistemological beliefs across 23 countries (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 2010, 2013). However, in relation to online and distance higher education, epistemological research is relatively absent (Richardson, 2013; Knight et al., 2017). Given the impact of epistemological beliefs on students’ study experiences there is a need for greater epistemologically focused research in the context of online education.

Another underrepresented research area concerns fun in online learning; in particular, because the meaning of fun is unclear and controversial. There is no consensus about the value of fun in learning and what a fun learning experience means in higher education (McManus and Furnham, 2010; Lesser et al., 2013; Tews et al., 2015; Whitton and Langan, 2018). Tews et al. (2015) argue that fun is a term used regularly in various contexts including education. Yet there is no clear agreement about its role and relationships with students’ learning experience. Congruently, McManus and Furnham (2010) highlight that fun has different meanings for different people and literature is limited about what generally comprises fun for learners. Similarly, Lesser et al. (2013) indicate that views about fun among educators are ambivalent as fun is perceived as too difficult or time-consuming to be implemented and it may distract students from serious learning. These three studies indicate that evidence about fun and learning are circumstantial and subjective for teaching staff to consider it as a compelling component for making their students’ experience more impactful. So that, further studies would be worthwhile to examine the practical meaning and educational value of fun on Distance Higher Education with a systematic and rigorous methodological approach.

To explore this challenge, this paper investigates students’ reflective views about fun and online learning and whether fun and enjoyment are interconnected components to enhance enthusiasm to learn and excel in online distant education. This investigation considers a critical question framed by the authors from Whitton and Langan (2018:11)’s work. How can we explore the impact of fun in higher education in view of the complexity of factors involved? To explore this question, this work is based on Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI) approach to understanding the what, how and why fun might be a valuable key in education with and for distinctive representatives: learners, educators, researchers, consultants, and policy makers. “For pedagogic innovation to succeed, learners must personally perceive the benefits of learning activities” designed to be fun and also “these gains must be translated into outcomes that are viewed positively within the institution quality monitoring by teaching staff.” Whitton and Langan (2018) also explain that there is a negative influence from the competitive job market that values “serious” performance – as the opposite of fun – so potentially this make course teams less likely to embed playful and fun approaches in the higher education curriculum.

The RRI approach implies that community-members and researchers interact together to better align both its process and outcomes with the values, needs and expectations of society (European Commission, 2013; von Schomberg, 2013). The purpose of RRI is to promote greater involvement of societal members with research-authors in the process of research to increase knowledge, understanding and better decision-making about both societal needs and scientific research through eight principles: diversity and inclusion; transparency and openness, anticipation and reflexivity, adaptation and responsiveness (RRI-Tools, 2016; European Commission, 2020). These principles were used to adapt, implement and refine a self-reflective instrument about learning and fun. So that, the following section-“Previous Studies about Fun and Learning” present Learning and Fun views from literature. Section-“Methodology” shows the self-reflective instrument, which was used integrated with the methodological approach. Section-“Findings” shows the findings and section-“Discussion and Final Remarks” discussion with final remarks.

Previous Studies about Fun and Learning

Studies that appear to research fun and learning, typically focus on types of activity and the extent to which these are seen as enjoyable and indicated as being fun, rather than drilling down to examine or define fun. While fun is consistently recognized as an important part of the lived experience of children, youth and adults, relatively few seek a deeper understanding of what the construct of fun means (Kimiecik and Harris, 1996; Harmston, 2005; Garn and Cothran, 2006). This situation is in stark contrast to how fun is generally positioned with regard to the domain of learning and education.

There are different views in the literature about fun and learning, in terms of meanings and its effects. Negative perspectives describe fun as the opposite concept of meaningful “work” and consider it as an unnecessary distraction for learning.

Fun is a term that has changed over time. In the 1900s, it came to indicate an absence of seriousness, work, and labor. “Fun can be seen both as a resistance to the rigid demarcation between work and leisure and also as a means of reproducing that dichotomy” (Blythe and Hassenzahl, 2018, p92). As it took on these meanings, fun became a loaded term that challenges the status quo (Beckman, 2014). It can be positioned as a challenge to the traditional split between fun and learning; welcomed by those who embrace social views of the learning process but seen as an unnecessary distraction for those who hold a traditional transmission view of how learning takes place.

The etymological meaning of fun (fonne and fon from Germanic), which refers to “simple, foolish, silly, unwise” (Etymonline, 2020) have still influence on the meanings attributed by people and researchers nowadays. The argument that fun can have a negative influence on learning was highlighted in newspaper reports of research by the Centre for Education Economics (CEE): “Making lessons fun does not help students to learn, a new report has found. The widely held belief that learners must be happy in order to do well is nothing more than a myth” (Turner, 2018). Likewise, Whitton and Langan note in their analysis of fun in United Kingdom that many educators believe fun to be unsuitable in the “serious” business of higher education (Whitton and Langan, 2018, p3). They also highlight a need to research whether students believe that there is any place for fun in their university studies. So, for many, fun is seen as having little or no place within learning. Within the context of education, “fun” is often a derogatory term used to refer to a trivial experience (Glaveanu, 2011).

Some researchers have identified a more positive relationship between fun and learning for children and adults. An analysis of outcomes from the United Kingdom’s “Excellence and Enjoyment” teaching initiative concluded that “Learning which is enjoyable (fun) and self-motivating is more effective than sterile (boring) solely teacher-directed learning” (Elton-Chalcraft and Mills, 2015, p482; Tews et al., 2015). In the context of informal adult learning, fun has been linked to positive learning outcomes, including job performance and learner engagement (Francis and Kentel, 2008; Fine and Corte, 2017; Tews et al., 2017). This raises the question of why this conflict and controversy might exist.

The positive effect is not due to fun being an integral part of the learning process, but rather because it has physiological effects such as reducing stress and improving alertness which enhance “performance” (Bisson and Luckner, 1996).

Similarly, Whitton and Langan (2018) describe fun as a “fluid state” (Prouty, 2002) which makes learners feel good (Koster, 2005: 40) to engage with learning. This fluid state allows learners to take healthy risks beyond existing personal boundaries (Ungar, 2007). This is because learners are attracted to participate in learning activities that they enjoy and can “fail forward” and feel safe. In addition, Feldberg (2011:12) indicate that fun has a positive effect on the learning process for creating a state of “relaxed alertness” (Bisson and Luckner, 1996) which enables the suspension of one’s social inhibitions and the reduction of stress. The author highlights fun may contribute to the maintenance of cognitive functioning and emotional growth (Crosnoe et al., 2004 cited by Feldberg).

Dismore and Bailey’s (2011, p.499) study indicates positive feelings associated with enjoyment, engagement and optimal experience. The authors described fun and enjoyment underpinned by the concept of “flow” (Csikszentmihalyi, 2015) which refers to “an optimum state of inner experience incorporating joy, creativity, total involvement and an exhilarating feeling of transcendence.” The optimum state is a key component to lead students to enjoyable accomplishment and optimal learning when their perceived skill and challenge are balanced and suitable. Flow is an important concept for educators to be aware that students’ anxiety caused when their challenge becomes higher compared to their skill, and boredom when challenge becomes too little compared to their skill will reduce their enjoyment and have a negative effect on their learning. Fun learning with flow experiences is relevant for learners to grow with positive opportunities where their skill meets their effort producing intrinsic rewards (Dismore and Bailey, 2011; Chu et al., 2017; Whitton and Langan, 2018).

Literature about the meaning of fun in online learning is very limited. A set of studies about engaging e-learning games highlight that fun and challenge are essential for promoting students’ enjoyment and making them want to learn (Fu et al., 2009). An engaging e-learning game facilitates the flow of experiences of students by increasing their attention, achieving learning goals and enjoyment with their learning experience (Virvou et al., 2005; De Freitas and Oliver, 2006).

This study focuses on fun and learning in the context of Distance Higher Education supported by RRI. To explore what fun is, its meaning and the effects of the phenomenon need to be understood with learners. As a first step, there is a need to identify how the relationship between fun and online learning is conceived by learners based on their own learning experience. A second step is to examine whether this relationship connection has any connection with their epistemic views.

The aim of this study is to address the following questions:

• What are the relationships between fun and online learning practices identified by students?

• What are the connections between students’ epistemic views about online learning and fun?

• What are the recommendations for students, teaching staff and course teams?

Methodology

This work is part of a research program OLAF – Online Learning and Fun led by Rumpus Research Group. The methodology used in this study adopts the established epistemological questionnaire approach (Feucht et al., 2017), and provides an opportunity to facilitate participants epistemic reflectivity (Feucht et al., 2017). In this way the study is underpinned by the concept of reflective practitioners, by which participants “think in action” about principles and practices to share their reflective views (Schon, 2015).

This study is based on a mixed-method approach. Quantitative and qualitative data were generated through a self-reflective instrument (Feucht et al., 2017) constituted by two parts, both developed in Qualtrics. The first part was a Likert-scale survey with 25 statements about learning and fun. The second part was an open question (see “Instruments”).

The approach used for qualitative analysis was a systematic and novel multi methodical procedure that combined: word cloud visualization in Qualtrics (Figure 2); automated thematic analysis map (Figure 3) and sentiment analysis (Figures 4–6) in NVivo 12. This integration of visualizations enabled us to identify seven themes to analyze the value of fun; and 26 themes of relationships between fun and learning. The quantitative analysis was supported by PCA – Principal Content Analysis (see “Relationships Between Fun and Learning Supported by Quantitative Analysis”). This approach enabled us to group our – multi-method qualitative analysis categorized by themes – into three groups (see “Relationships Between Fun and Learning Supported by Quantitative Analysis”) as well present our findings (section-“Findings”) with global recommendations underpinned by students’ needs, priorities and expectations, which were revealed in the qualitative data and grouped by quantitative analysis.

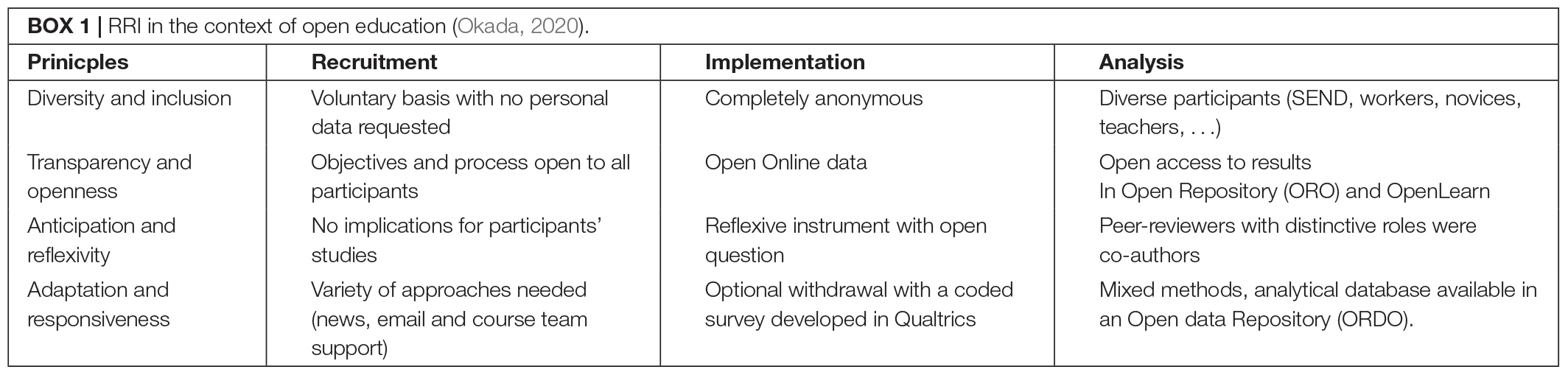

This study acknowledges 8 principles (Box 1) of RRI (von Schomberg, 2013; RRI-Tools, 2016) in the context of open educational research (Okada and Sherborne, 2018) by which all participants reflect about practices and beliefs for better alignment between learners’ needs and research-based recommendations. The instrument with a special code to allow the withdrawal of participation without the collection of personal data was approved by the Ethics Committee and the Student Research Project Panel of the Open University-United Kingdom.

Participants

The OU offers flexible undergraduate and postgraduate courses and qualifications supported distance and open learning for 174,898 people from the United Kingdom, Europe and some worldwide. Approximately 76% of directly registered students work full or part-time during their studies; 23% of Open University United Kingdom undergraduates live in the 25% most deprived areas and 34% of new OU undergraduates are under 25, 14% with disabilities and 32% with lower qualification at entry.

This study focused on one of the largest introductory modules offered by the Wellbeing Education and Language Studies – WELS Faculty of The Open University. Currently this module has more than 4,300 students and is part of various qualifications. So that, participants were students from all levels and qualification’ interests with different occupations, include novices, undergraduates who had just completed secondary education, pre-service and in-service teachers; as well professionals interested in Education, Psychology and Social Care.

A balanced and representative sample were constituted by a total of 625 students who participated in this study as volunteers, 551 completed a self-reflective questionnaire to reflect about fun and learning and 206 provided their reflective views by answering an “optional” open question. The response rate (40%) for the open views about fun and learning was higher than expected.

In terms of students’ previous study experience 48.55% students completed pre-A levels or equivalent (secondary school), 26.81% had already finished other OU course modules (level 1, level 2, and level 3) and 24.64% reported other different experiences. In terms of qualification pathway targeted by students: 28.80% are interested in childhood studies; 34.24% in psychology; 27.17% Education primary, 4.53% Open and 1.81% do not know and 3.44 other qualification such as Social Care.

Procedures

This study focuses on a 9-month-module course with twenty-four weekly units and four assessment activities. The course integrates reading materials, online audio-visual materials, a YouTube channel “The student hub live” and radio-style broadcast audio repository. Students have also access to a set of library resources, news and special “quick guides” to provide extra-support for developing activities successfully. Students’ interaction with peers and communication with tutors typically occur asynchronously in the online discussion forum and synchronously in online tutorials (in Adobe Connect) and face-to-face tutorials organized in a specific period and locations. In addition, the course provides a channel in social media (Twitter and Facebook) for students’ social engagement. This course module presentations are opened 3 weeks prior to the start in order to provide time for students to smoothly engage in their initial activities including a series of fun and friendly online workshops to promote interaction.

Recruitment

Students’ recruitment occurred at the middle of the online module. It was supported by the course chair and the module course tutors through an invitation shared in course news page and via central email sent to all students. Recruitment and data generation occurred during 5 weeks (February–March 2020) and was more effective after an email invitation sent to all students.

Instruments

The use of self-report questionnaires is well established as a methodology within research examining epistemological beliefs (Feucht et al., 2017). The self-reflective instrument was underpinned by previous work led by the second author (Sheehy et al., 2019b) and adapted to the context of online learning and fun.

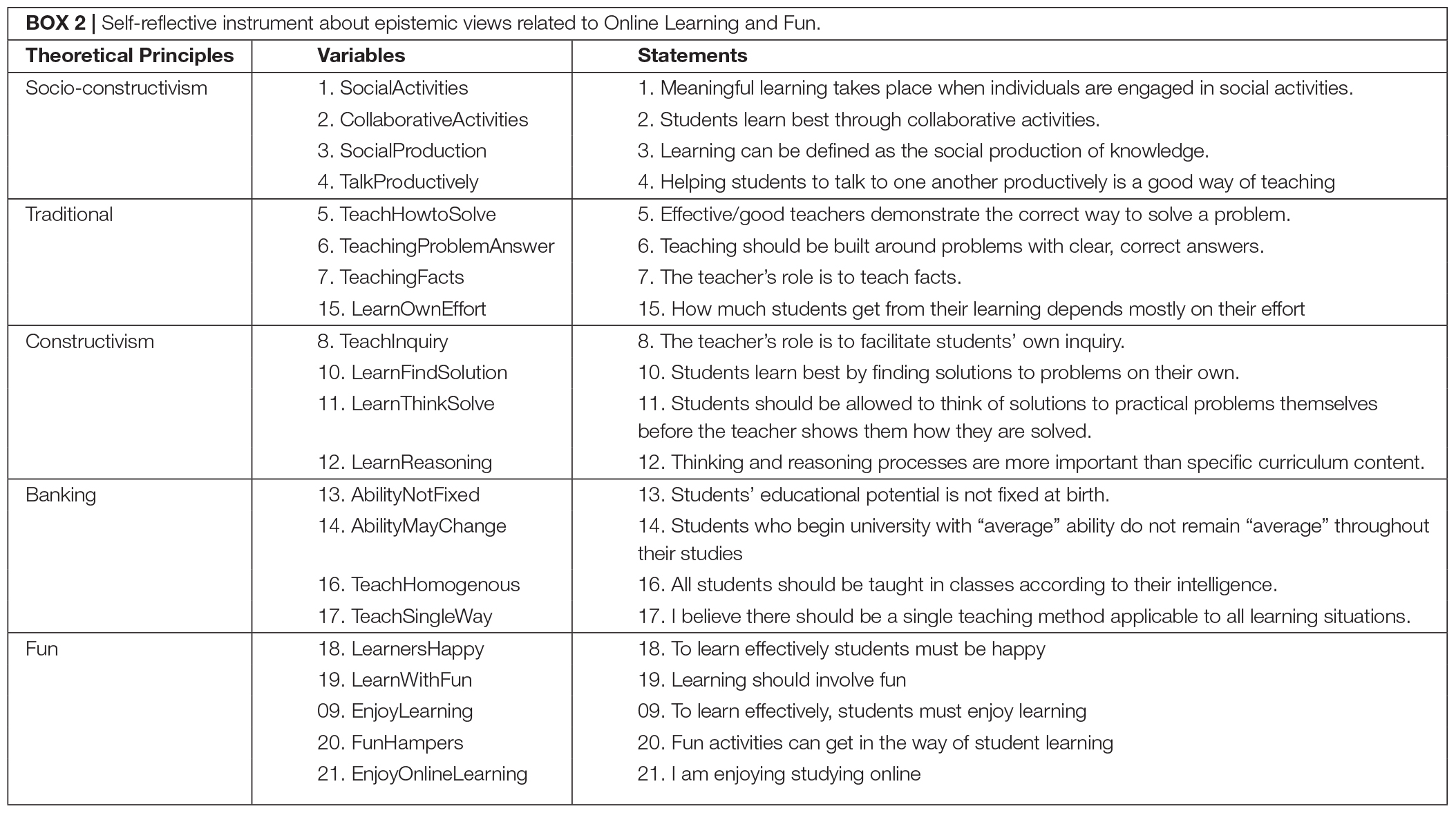

1. Statements 1–4, 13–17 relate to models of learning (Social Constructivist, and Banking) and are taken from Sheehy and Budiyanto’s (2015) development of the Theoretical Orientation Scale (Hardman and Worthington, 2000).

2. Statements 5–7, 8, 10–12 relate to Constructivist and Traditional views of learning, from the OECD international survey (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 2010, 2013).

3. Statements 9, 18–21 elicit beliefs about fun and happiness and emerged as stable items from Budiyanto et al.’s (2017) epistemological research.

The adapted questionnaire was implemented in Qualtrics with consent forms, study objectives and a novel embedded code to enable students’ withdrawal. This is the first study that provides anonymous withdrawal in Qualtrics. It was then tested in two pre-pilots to check its reliability and the embedded code.

In the first phase of implementation, the self-reflective instrument was used by online students to reflect about the topic “Fun and Learning” through a series of 21 statements using Likert-scale to indicate the level of agreement.

In the second phase, students were invited to complete an optional open-ended question (What is your opinion about fun in online learning?) to provide their reflective views and freely express their feelings on this topic.

Findings

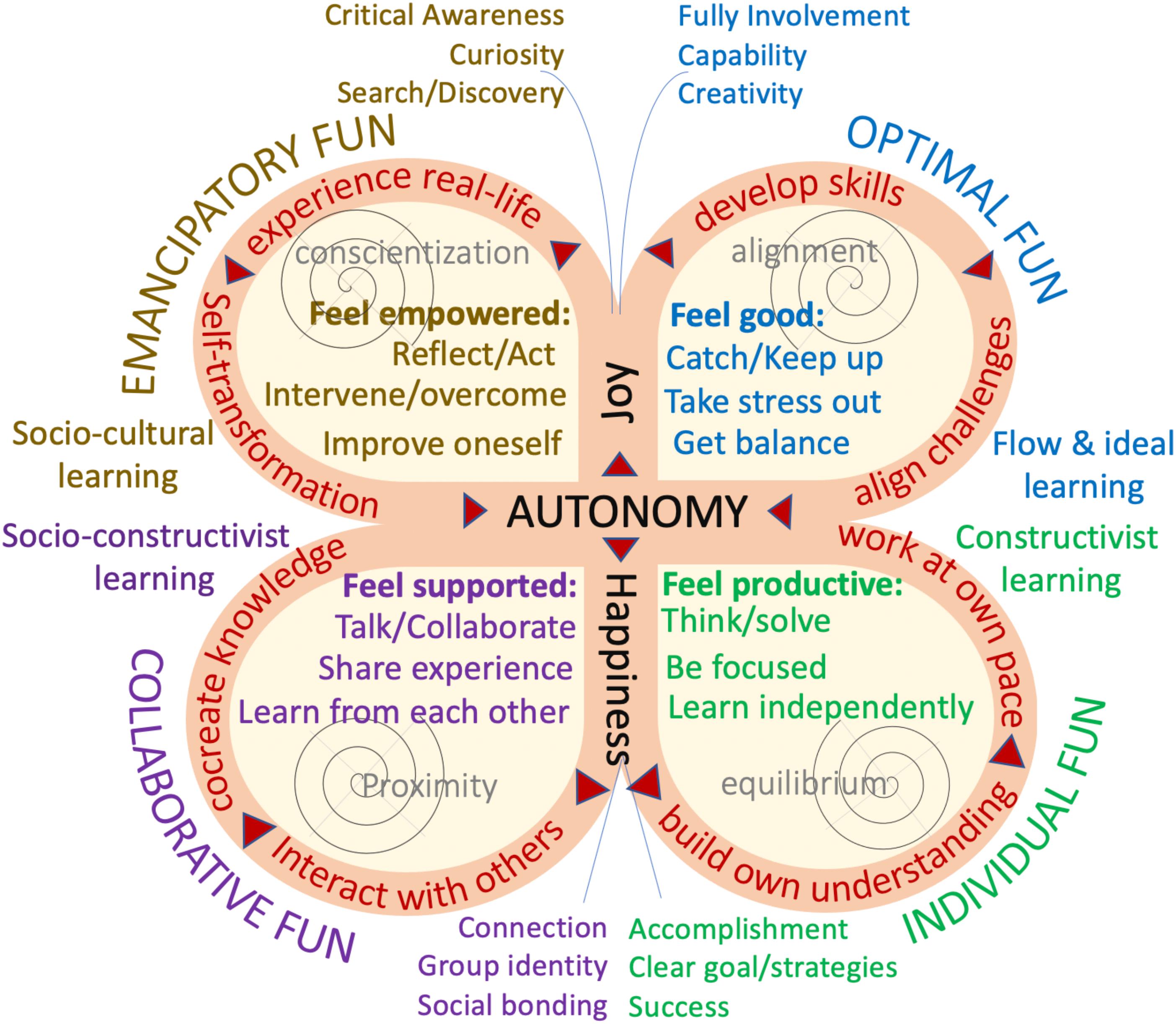

Preliminary outcomes of this study (Figure 1) were presented to all participants through an article published in OpenLearn (Okada, 2020) and also in a journal paper (Okada and Sheehy, 2020: 608). The framework ‘Butterfly of fun’ including four types of fun in online learning was developed underpinned by Piaget and Inhelder (1969), Vygotsky et al. (1978), Csikszentmihalyi (2020), and Freire (1967, 1984, 1996, 2009) and supported by students’ views. Optimal fun is the joy of being fully involved in learning, moving toward full capability and creativity. Individual fun is the happiness of fulfilling accomplishments, supported by clear goals and strategies. Collaborative fun is the happiness of making connections with others, creating social bonding and developing group identity. Emancipatory fun is the joy of being curious, able to search and discover whilst being critically aware (Okada and Sheehy, 2020).

Figure 1. Four levels of Online Learning and Fun (Source: Okada, 2020).

Relationships Between Fun and Online Learning Supported by Qualitative Analysis

This study started with a content analysis in NVivo 12 after importing from Qualtrics a csv file with 206 responses about students’ views related to fun and learning (qualitative data). The word cloud visualization in Qualtrics (Figure 2) about students’ views indicated the most frequent words: 148 fun, 123 learning, 50 enjoy/enjoyed/enjoyable/enjoyment, 45 students, 40 distance, 31 tutorials, 29 activity, and 26 time.

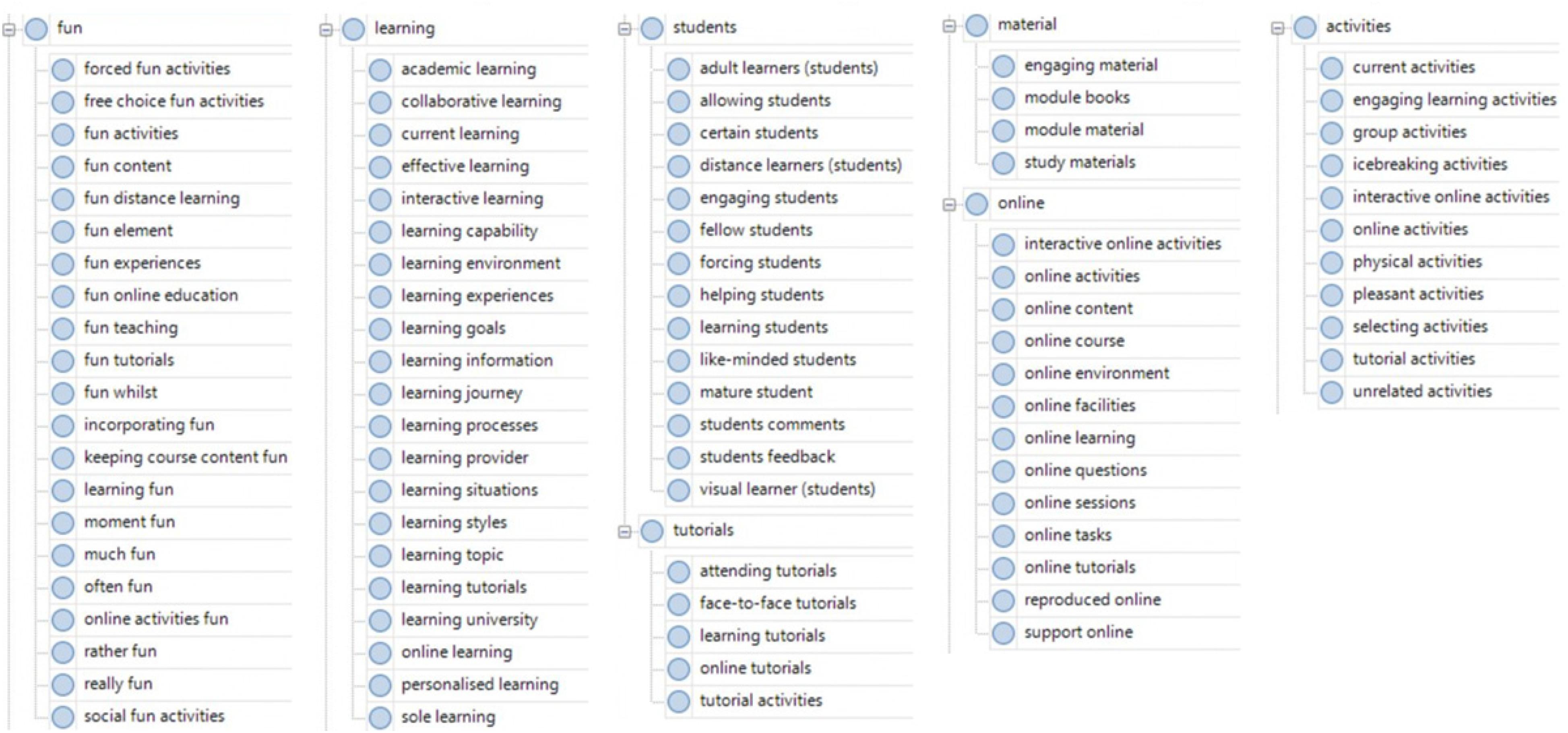

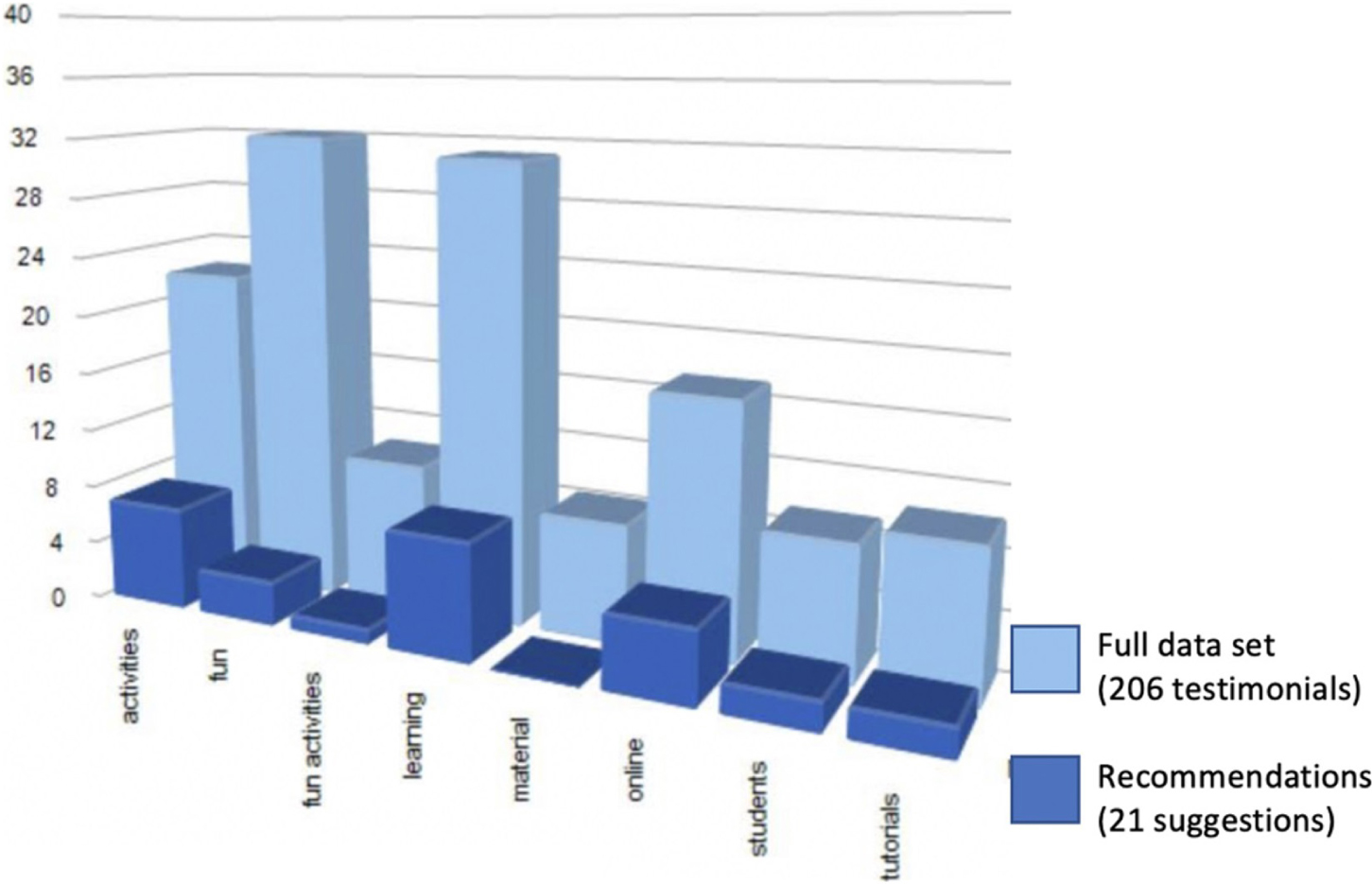

The automated thematic analysis map (Figure 3) in NVivo 12; represented in Cmap tools provided 89 codes grouped through seven themes: fun, learning, students, tutorials, material, online and activities, which enabled to identify connections between fun and learning presented as following.

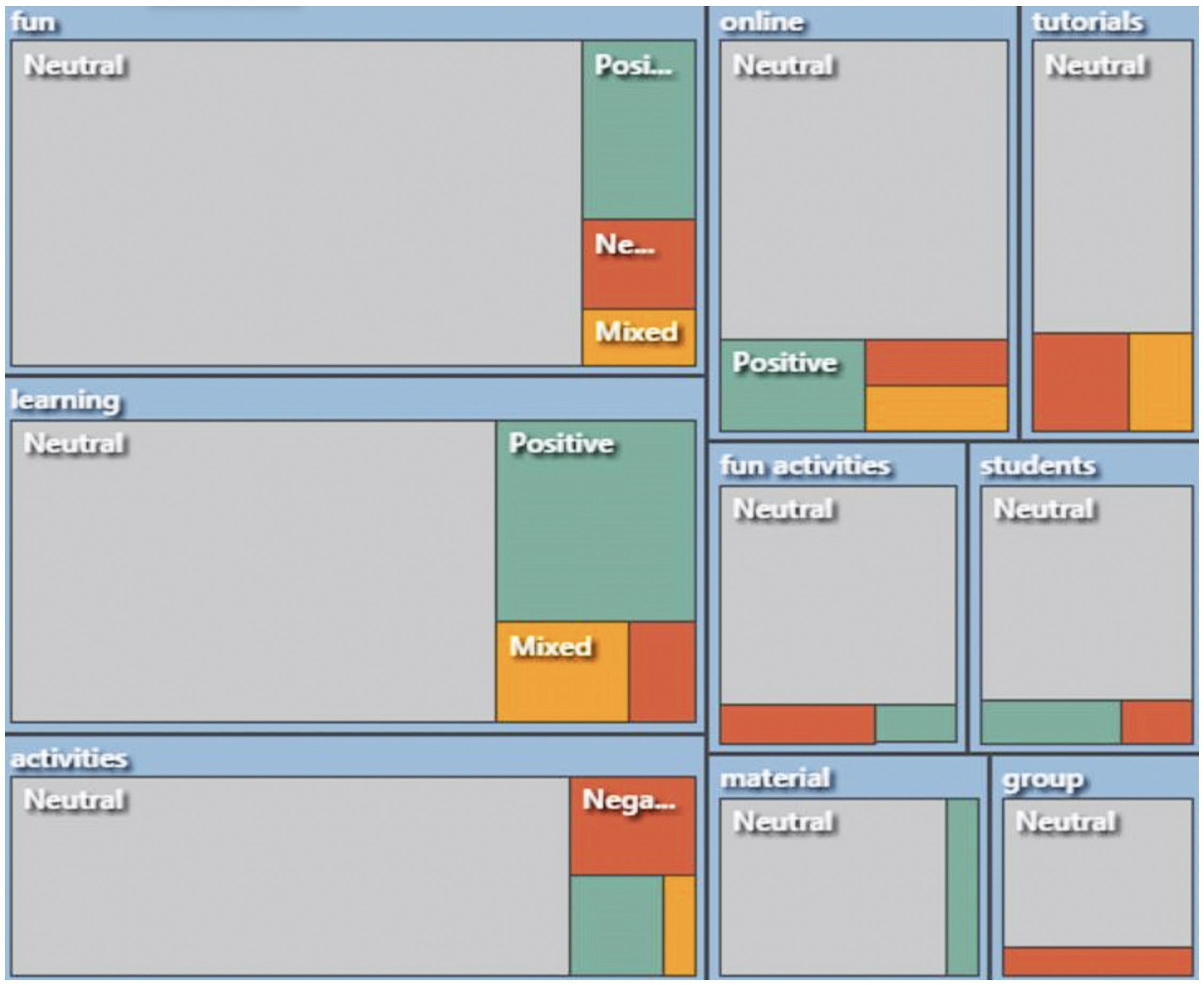

NVivo12 sentiment analysis tool (Figure 4) indicated a significant amount of neutral and positive comments associated to narratives that included learning and fun. A small percentage of negative and mixed views emerged across all categories apart from course module “material.” Three largest clusters emerged focused on fun, learning and activities. Four medium clusters were online, tutorials, fun activities, and students. Two small clusters were material and group.

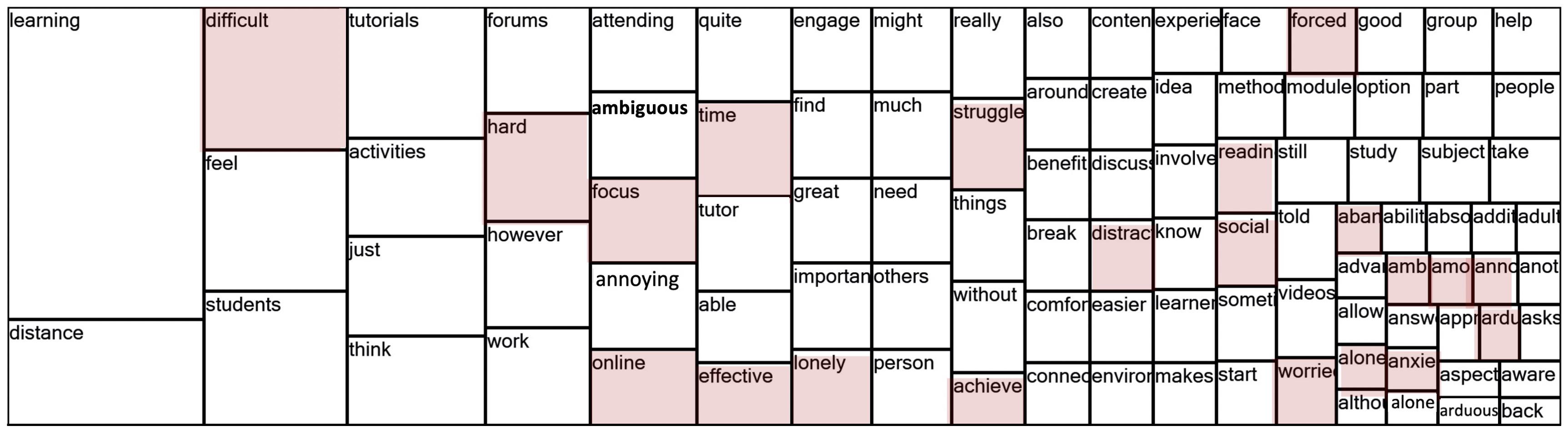

NVivo 12 sentiment analysis were used to obtain an overview about students’ negative views (Figure 5) and positive opinions (Figure 6) which were highlighted in red and green by the authors to show the students’ responses with a significant narrative.

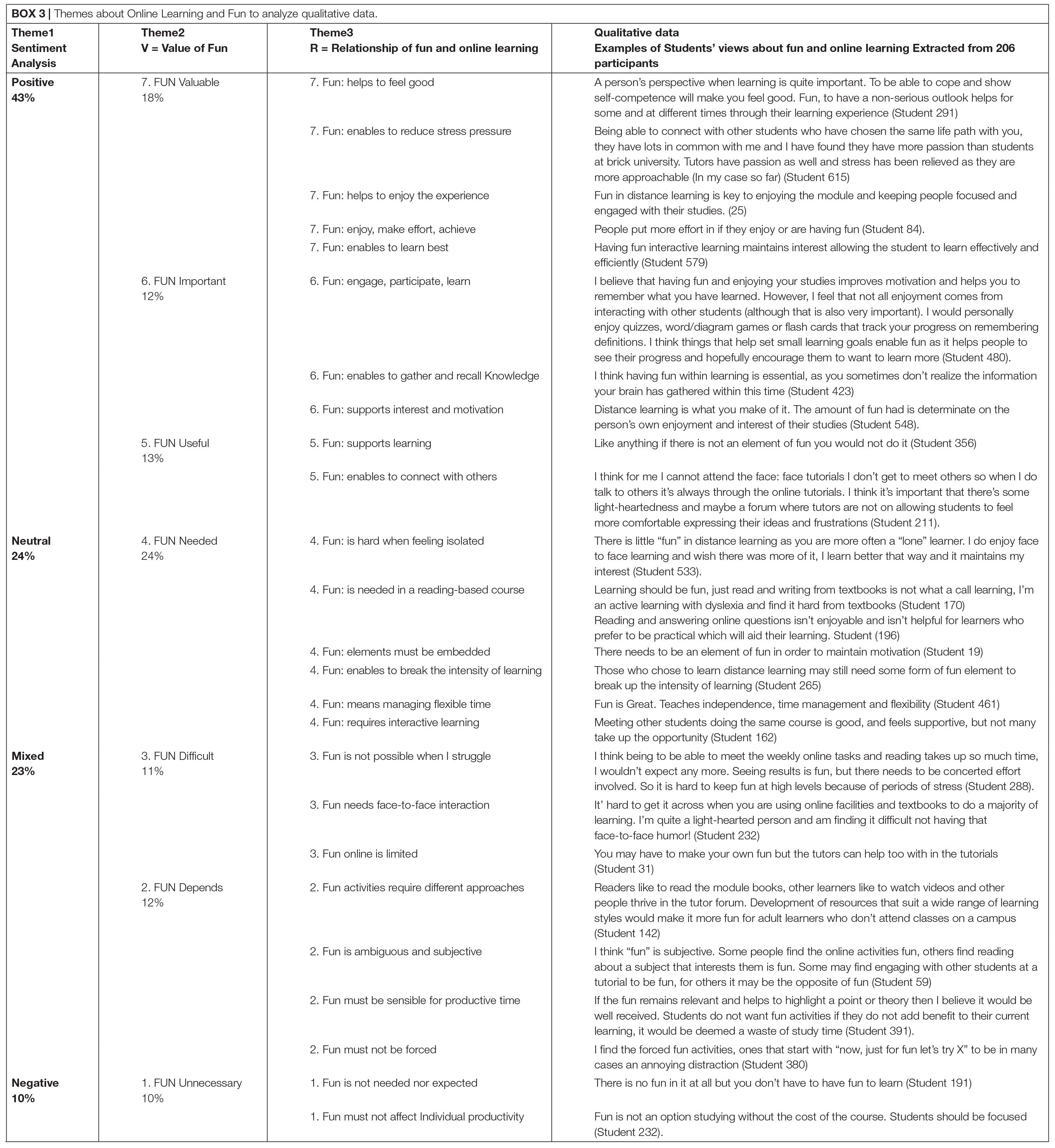

These visualizations were useful to identify two sets of themes and sub-themes (Box 3) related to value and relationships between learning and fun as well review the automated sentiment analysis code manually to check nuances and recode it based on the meaning of narratives.

A total of 206 students’ testimonials were coded with these themes and the frequency of codes were represented by percentages (Box 3). The first set of themes was used to code the value of fun for students; a total of 43% students indicated positive values about fun in learning, 24% indicated neutral, and 23% mixed. Only 10% indicated negative views about fun in learning. The second set of themes were used to explore the value and relationships about fun and learning. Approximately 18% of students indicated that fun is valuable, 12% fun is important, 13% fun is useful, 24% fun is needed, 11% fun is difficult, 12% fun depends, and 10% fun is unnecessary.

Relationships Between Fun and Learning Supported by Quantitative Analysis

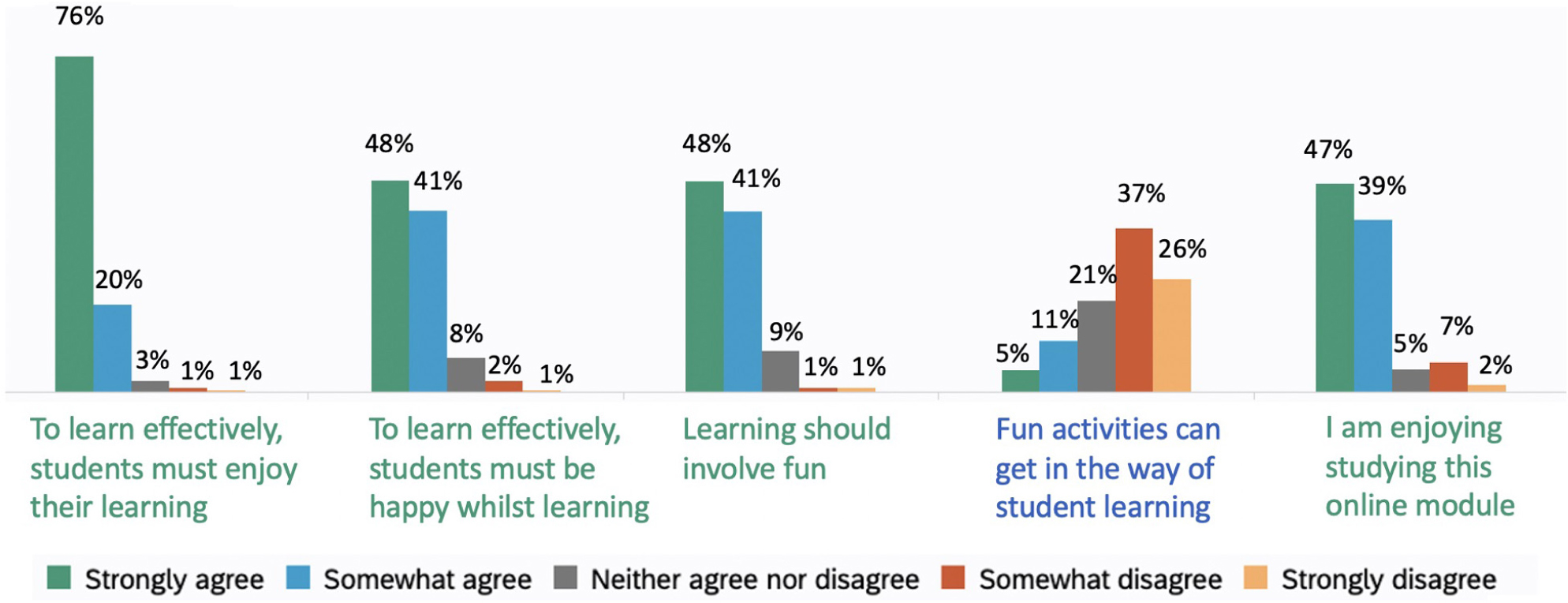

Quantitative data analysis (Graph 1) revealed largely positive views about fun and learning. Most students agreed that fun (as enjoyment) had value in supporting learning. The majority of students agreed with the following statements: 98% To learn effectively, students must enjoy learning; 91% To learn effectively, students must be happy to learn. 88.77% Learning should involve fun. However, a small group of students 16.66% beliefs that Fun activities can get in the way of student learning.

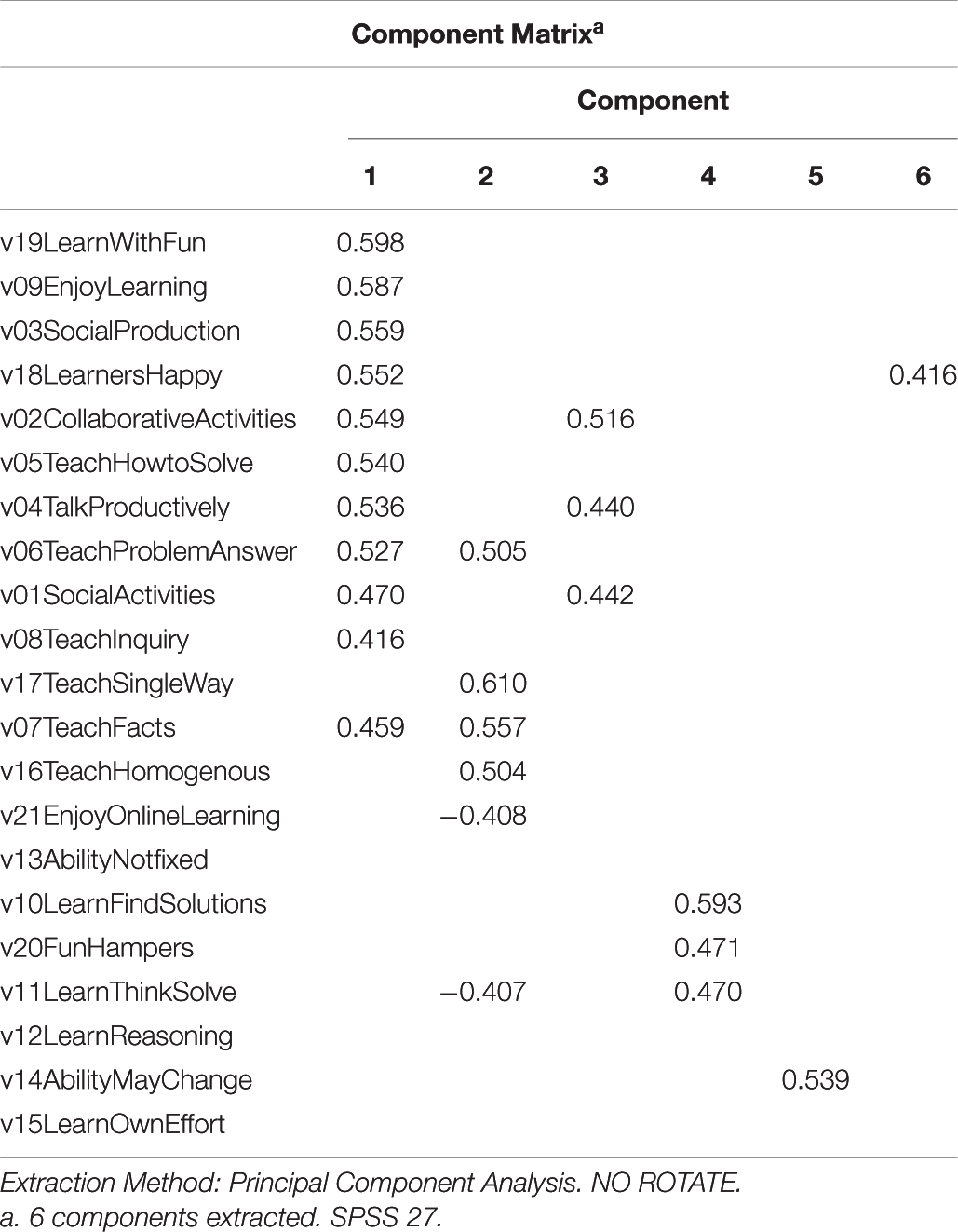

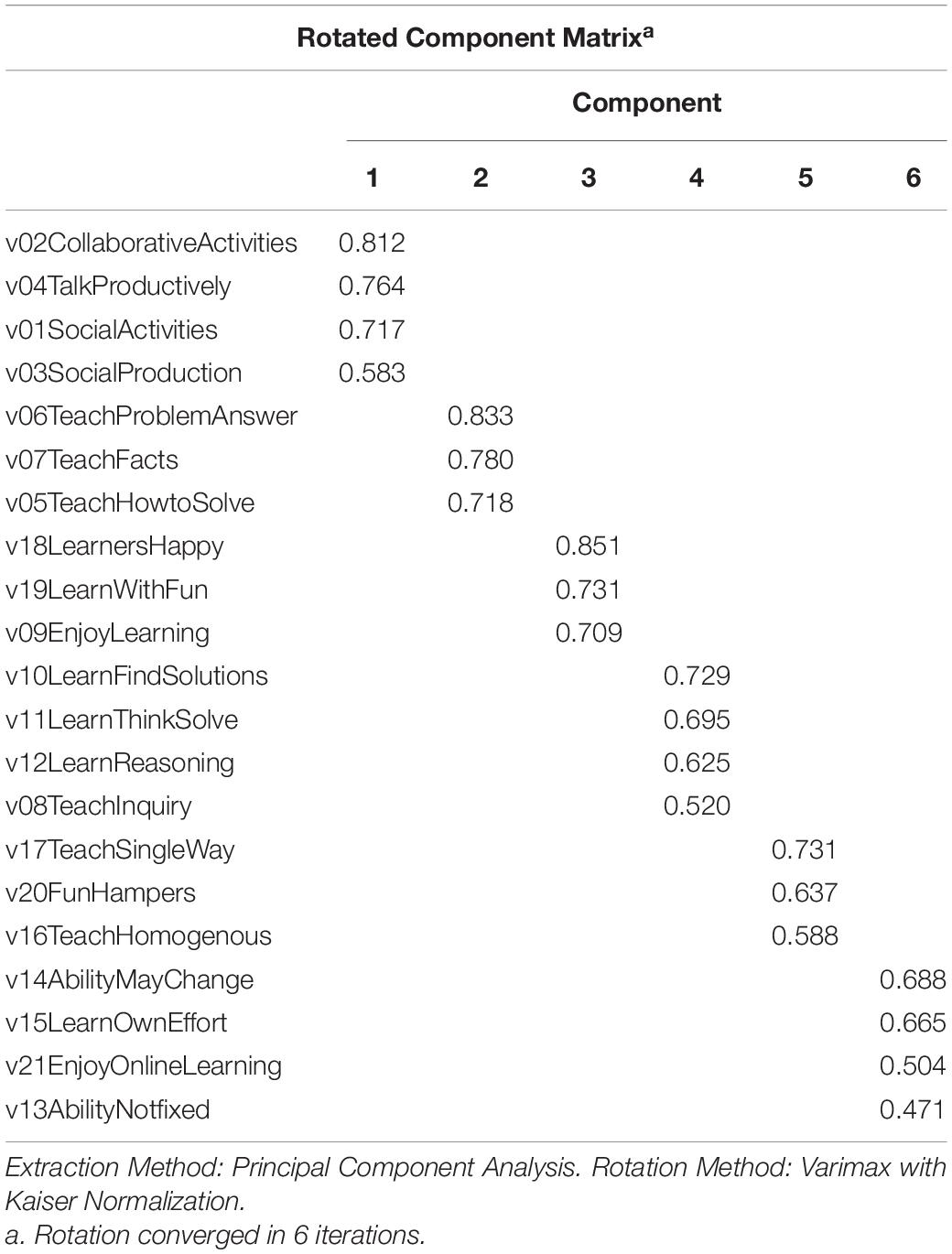

The questionnaire data about 21 statements using Likert scale (1–5) were analyzed through SPSS 24. Cronbach’s alpha 0.717 confirmed that the principal components analysis (PCA) was supported (Cohen et al., 2007). The instrument proved to be reliable for both PCAs (Tavakol and Dennick, 2011). The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin score of 0.756 indicated sample adequacy and the Bartlett’s sphericity test (Chi-square = 2329.046 with 210 degree of freedom, Sig. 0.000 < 0.5) confirmed consistency.

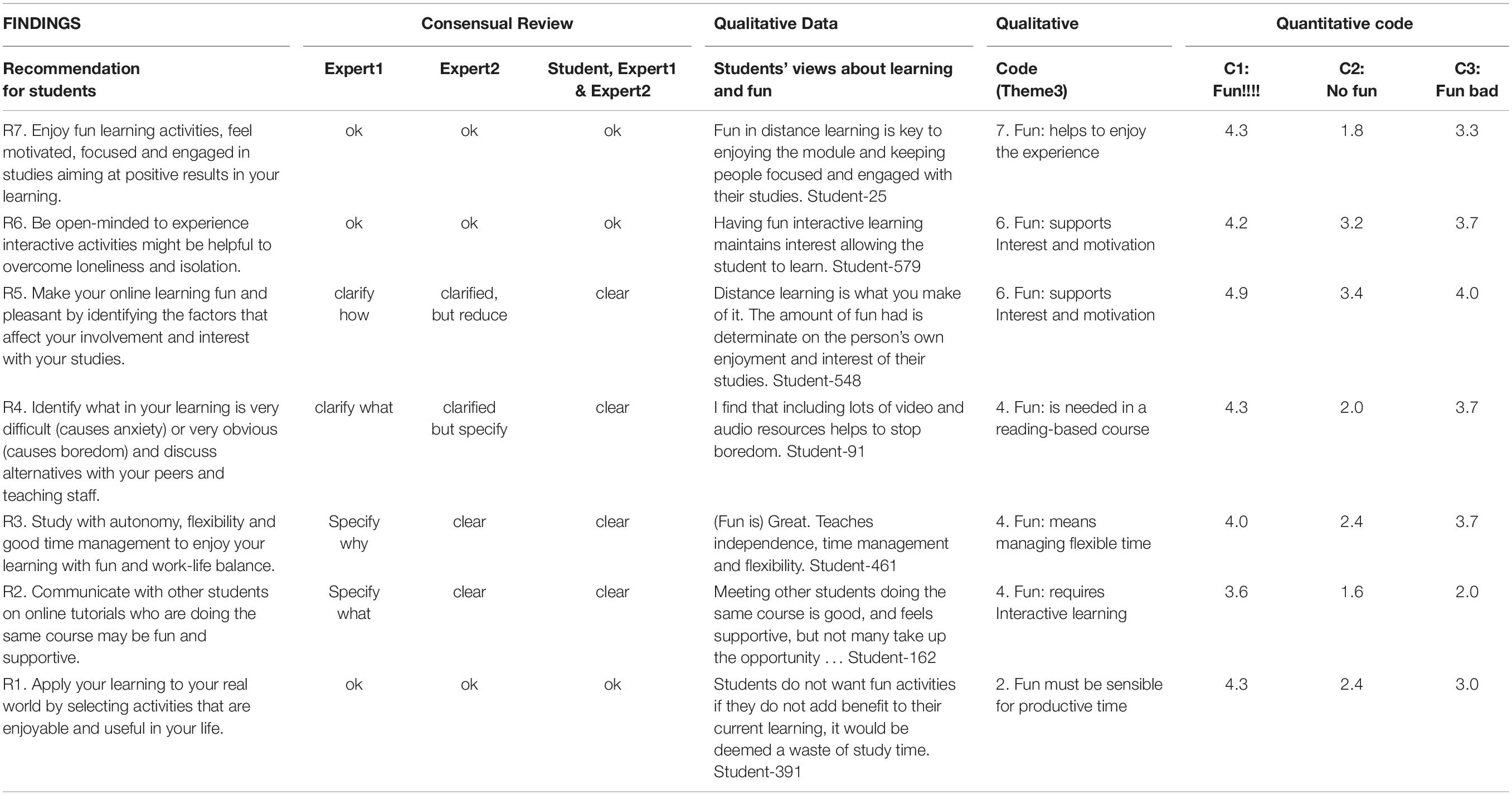

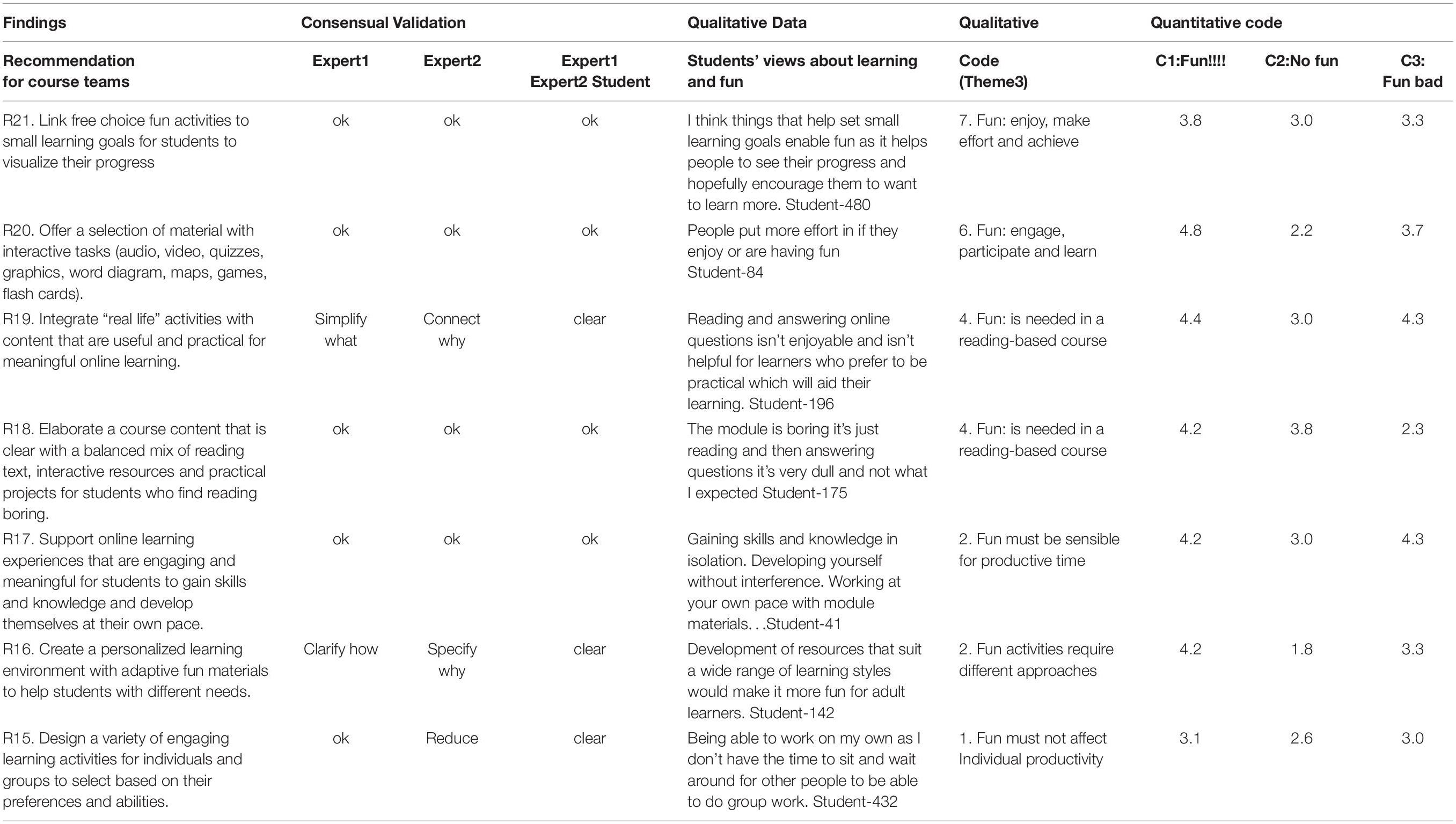

Table 2 illustrates factor analysis with principal components, with Varimax rotation and Kaiser Normalization indicated six groups emerged: (1) socio-constructivist perspective, (2)traditional perspective (3) fun and learning perspective, (4)constructivist perspective, (5) banking perspective, and (6) Emancipatory Learning. Table 1 using the same method but unrotated solution, indicated three relevant groups: (1) Socio-constructivist learning with traditional teaching and fun; (2) Banking model, transmissive learning and no fun and (4) Constructivist learning and disturbing fun; This approach was selected to examine students’ views and beliefs in order to develop recommendations. Therefore, based on the testimonies of the students grouped with PCA unrotated, twenty-one recommendations were listed and grouped according to three groups: apprentices, teaching professionals and the online course team. Three indexes were generated using the variables from the PCA to get an average among each group related to Fun, No Fun and Bad fun:

• C1 Fun = (V19 + V09 + V03 + V18 + V02 + V05 + V04 + V01 + V08)/9;

• C2 No fun = (V17 + V07 + V16 + V06 + -V21)/5;

• C3 Fun bad (hampers learning) = (V10 + V20 + V11)/3.

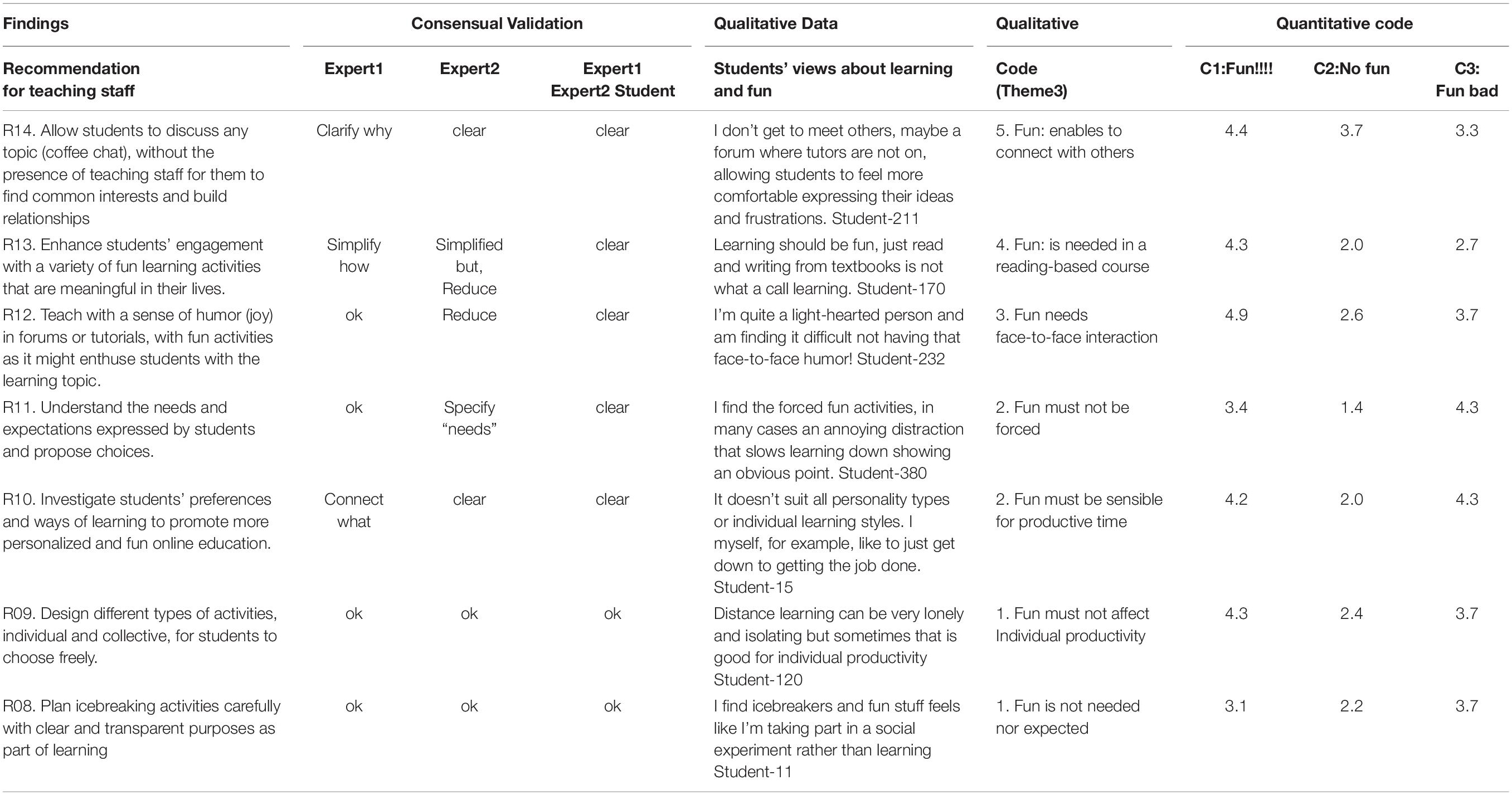

These indexes (above 3.5 – 5) allowed to group participants’ testimonies, select a variety of views and elaborate a representative list of recommendations to enhance students’ enjoyment with online learning. NVivo 12 was used to carry out a thematic qualitative analysis with an interpretative approach to extract 21 recommendations supported by inductive mapping (Tables 3–5). A consensual review (Hill et al., 1997) through three systematic checks between the recommendations against qualitative data were developed with two experts and a student: individually, in pairs and in group. Five types of feedback enabled reviewers to suggest improvements: 1. Reduce (too long, use short sentence), 2. Specify (very broad, use specific words), 3. Connect (unrelated, focus more on the data), 4. Simplify (complicated, use familiar vocabulary), 5. Clarify (confusing, revise the meaning). The results of the analysis from mixed methods are presented as follows.

Table 4. Recommendations about Online Learning and Fun for teaching staff supported by mixed methods.

In addition, the graphical comparison between recommendations and full set of qualitative data both auto coded (Figure 3) in NVivo 24 (Graph 2) ensured diversity with a variety of views and consistency with a proportional representation among qualitative themes and quantitative components.

Graph 2. Evidence-based recommendations about Online Learning and Fun supported by consensual review.

Discussion and Final Remarks

The value of students’ enjoyment with online learning has become fundamental in today’s world. The World Bank (2020) and UNESCO (2020) emphasized that more than 160 countries are facing a crisis in education due to the COVID-19 pandemic with loss of learning and in human capital; and over the long term, the economic difficulties will increase inequalities. Various factors will affect educational systems; in particular, low learning outcomes and high dropout rates in secondary school and higher education.

Students’ confidence and satisfaction with online learning are highly relevant in a world in which distance education has rapidly become a necessary practice in response to the global the pandemic. This mixed-methods research revealed significant online students’ opinions about fun for enjoyable and meaningful learning. Fun is as an important part of the lived experience; however, its meaning is underexplored by literature.

This paper provided a methodology to examine fun in online learning supported by students’ epistemic beliefs, underpinned by RRI – Responsible Research and Innovation. A self-reflective instrument with valid and reliable measurement scales with epistemic constructs of online learning and fun helped participants to think about their views about how learning occurs and its relationship with fun. An open database with a three sets of code scheme was generated and shared with all participants during the covid-19 pandemic.

In this study, light is shed on the elements, meaning and relationships about fun and learning considering the students’ “nuanced views” that integrate fun and learning in different ways. Our results provided evidence that a large majority of higher education students (88.77%) value fun because they believe it has a positive social, cognitive and emotional effects on their distance online education. A small group (16.66%) highlighted that fun impairs learning.

This study confirmed that students should experience enjoyable learning so that learning should involve joy. Freire (1996) highlight that the joy of the “serious act” of learning does not refer to the easy joy of being inactive by doing nothing. “Emancipatory fun” (Okada and Sheehy, 2020) underpinned by Freire’s pedagogy of autonomy is related to the hope and confidence that students can have fun by acting, reflecting and learning with enjoyment and consciousness. They can search, research and solve problems, identify and overcome obstacles as well transform and innovate their lives with knowledge, skills and resilience to shape a desirable future.

A key contribution of this study is that different epistemological beliefs are associated with different conceptualizations of the relationship between fun and learning (Sheehy et al., 2019a; Okada and Sheehy, 2020). Principal component analysis revealed three groups of students who found (1) fun relevant in socio-constructivist learning (2) no fun in traditional transmissive learning and (3) disturbing fun in constructivist learning. A set of 21 recommendations underpinned by systematic mixed methods and consensual review is provided for Higher Education community including course teams, teaching staff and students to enhance online learning experiences with optimal fun, emancipatory fun, collaborative fun and individual fun. Creating opportunities for students to voice and reflect on their own views and values is fundamental to develop more effective online course designs aligned with their needs.

Congruent with the positive effects of optimal experience in some online environments’ studies (e.g., Esteban-Millat et al., 2014; Sánchez-Franco et al., 2014), this study confirmed that fun creates an opportunity and expectation for students to experience positive feelings in learning such as good mood, enthusiasm, interest, satisfaction and enjoyment that are all relevant for “optimal” learning.

Researchers who see fun as having a close relationship with learning have proposed different types of fun. Lazzaro (2009) highlighted “easy fun” in activities such as games and role play that stimulate curiosity and exploration. Papert (2002) identified “hard fun” within goal-centered and challenging experiences, where the difficulty of the task is part of the fun. Tews et al. (2015:17) examined fun in two contexts, fun in learning activities developed by students and fun in teaching delivery by the staff. The former was characterized as “hands-on” exercises and activities that promoted social engagement between students. The latter concerned instructor-focused teaching that included the use of humor, creative examples, and storytelling. Their findings indicated that fun delivery, and not fun activities, was positively associated with students’ motivation, interest and engagement.

Notably, their findings indicated fun delivery, but not fun activities, was positively related to student’ motivation, interest and engagement. Prior examining activities and delivery, our study highlights the importance of investigating students’ epistemic views. There is therefore the opportunity for novel research to examine factors and effects of fun and student learning experience including epistemic-guided learning design.

Our study highlights the importance of investigating students’ epistemic beliefs and its connections with the essence of their views. There is therefore the opportunity for novel research to examine factors and effects of fun and within student learning experience including the influence of epistemic-guided learning and teaching design.

A series of studies with Indonesian teachers (Sheehy et al., 2019a) suggested that their beliefs about how learning occurs are influenced by their views about happiness and, by implication, fun in relation to learning. These teachers often commented on the relationship between happiness and learning, and many saw happiness as an essential feature of good classroom teaching. However, they described a relationship between happiness and learning that was different in nature to that found in Western educational research. There is a tendency for Western educators to see happiness as “a tool for facilitating effective education” (Fox et al., 2013, p1), and as something that is promoted alongside educational excellence. In contrast, many Indonesian teachers see learning not as separate from happiness but as part of it (Budiyanto et al., 2017; Budiyanto and Sheehy, 2019).

Other research has implied that this belief in separation arises when people see teaching as a simple transfer of “untransformed knowledge” from expert to student, in a traditional model of learning (OECD, 2009) also known as the “banking model of education” Freire (2000). This separation may be reflected in the balancing act between happiness with fun and academic achievement described in the CEE report mentioned above. In contrast, those who believe that learning is a social constructivist process are more likely to see happiness with fun as important to the process of learning. The situation remains that we have an incomplete understanding of fun in the domain of learning (Tews et al., 2017) and it remains to be clarified by empirical research (Iten and Petko, 2016); in particular under the lens of epistemological beliefs (Sheehy et al., 2019a) and practical experiences.

Our study also complemented a previous research about fun on traditional university’ campus whose students highlighted that fun in learning must integrate stimulating pedagogy; lecturer engagement; a safe learning space; shared experience; and a low-stress environment (Whitton and Langan, 2018). Some key effects of fun, for example, pleasant communication and creation of a relaxed state to reduce stress (Bisson and Luckner, 1996) are important factors to support learners during the isolation. Fun as an inner joy of wellbeing and engagement is an important component to propitiate learning with the creation of new patterns that are interesting, surprising and meaningful (Schmidhuber, 2010) to involve students with formal education during uncertain time of post-pandemic.

As indicated by the research-authors and collaborators, further studies are important based on the RRI approach to construct new questions and also explore the issues indicated by preliminary studies (Okada and Sheehy, 2020). New issues must be also examined on the effects of fun on online learning, also considering age, gender, socio-cultural aspects, accessibility, digital skills, and geographical differences. Developing further recommendations at broader institutional, national and international levels about effective and engaging online learning is also important to empower individuals and society to face, innovate and reconstruct a sustainable and enjoyable world.

Data Availability Statement

The open database can be accessed, downloaded and reused: Okada and Sheehy (2020) OLAF PROJECT data set. Open Research Data Online. The Open University. https://doi.org/10.21954/ou.rd.12670949 (November 2020). The Open Questionnaire can be accessed from the supplementary material Qualtrics Survey OLAF project.pdf.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by The Open University, HREC – Human Research and Ethics Committee. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

AO wrote the first draft of the abstract and prepared the manuscript. KS provided the instrument and feedback about the final version. AO was responsible for the survey implementation in Qualtrics, data generation, instrument’s tests, data analysis through mixed methods, and validation supported by collaborators with consensual review. Additionally, AO created the figures, graphs, and tables. Both authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding

This study was funded by the Open University UK and is part of the international project OLAF – Online Learning and Fun. http://www.open.ac.uk/blogs/rumpus/index.php/projects/olaf/.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to our collaborators who supported the recruitment of participants, our expert colleagues Prof. Dr. Daniela Melaré Barros; Prof. Dr. Maria Elizabeth de Almeida; Dr. Victoria Cooper, and Miss Ana Beatriz Rocha who provided valuable feedback and our external reviewers for useful suggestions.

References

Arnone, M. P., Small, R. V., Chauncey, S. A., and McKenna, H. P. (2011). Curiosity, interest and engagement in technology-pervasive learning environments: a new research agenda. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 59, 181–198. doi: 10.1007/s11423-011-9190-9

Beckman, J. (2014). American Fun: Four Centuries of Joyous Revolt. New York, NY: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group.

Bisson, C., and Luckner, J. (1996). Fun in learning: the pedagogical role of fun in adventure education. J. Exp. Educ. 19, 108–112. doi: 10.1177/105382599601900208

Blythe, M., and Hassenzahl, M. (2018). The semantics of fun: differentiating enjoyable experiences. Funology 2, 375–387. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-68213-6_24

Budiyanto Sheehy, K. (2019). “Developing Signalong Indonesia: issues of politics, pedagogy and perceptions,” in Manual Sign Acquisition by Children with Developmental Disabilities, eds N. Grove and K. Launonen (Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science).

Budiyanto, Sheehy, K., Kaye, H., and Rofiah, K. (2017). Developing Signalong Indonesia: issues of happiness and pedagogy, training and stigmatisation. Int. J. Inclusive Educ. 22, 543–559. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2017.1390000

Chan, K. W., and Elliott, R. G. (2004). Relational analysis of personal epistemology and conceptions about teaching and learning. Teach. Teach. Edu. 20, 817–831. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2004.09.002

Chu, S. L., Angello, G., Saenz, M., and Quek, F. (2017). Fun in Making: understanding the experience of fun and learning through curriculum-based Making in the elementary school classroom. Entertain. Comput. 18, 31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.entcom.2016.08.007

Cohen, L., Manion, L., and Morrison, K. (2007). Research Methods in Education, Sixth Edn. Abingdon: Routledge.

Cooperman, L. (2014). “Foreword,” in Open Educational Resources and Social Networks: Co-Learning and Professional Development, ed. A. Okada (London: Scholio Educational Research & Publishing).

Crosnoe, R., Johnson, M. K., and Elder, G. H. Jr. (2004). Intergenerational bonding in school: The behavioural and contextual correlates of student-teacher relationships. Sociol. Educ. 77, 60–81. doi: 10.1177/003804070407700103

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2015). The Systems Model of Creativity: The Collected works of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. Springer.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2020) Finding Flow: The Psychology of Engagement with Everyday Life. Hachette.

De Freitas, S., and Oliver, M. (2006). How can exploratory learning with games and simulations within the curriculum be most effectively evaluated? Comput. Educ. 46, 249–264. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2005.11.007

Dismore, H., and Bailey, R. (2011). Fun and enjoyment in physical education: young people’s attitudes. Res. Papers Educ. 26, 499–516. doi: 10.1080/02671522.2010.484866

Elton-Chalcraft, S., and Mills, K. (2015). Measuring challenge, fun and sterility on a ‘phunometre’scale: evaluating creative teaching and learning with children and their student teachers in the primary school. Education 3-13 43, 482–497. doi: 10.1080/03004279.2013.822904

Esteban-Millat, I., Martínez-López, F. J., Huertas-García, R., Meseguer, A., and Rodríguez-Ardura, I. (2014). Modelling students’ flow experiences in an online learning environment. Comput. Educ. 71, 111–123. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2013.09.012

Etymonline. Dicionário etimológico. Available online at: https://www.etymonline.com/word/fun (accessed May 12, 2020).

European Commission (2013). Options for Strengthening Responsible Research and Innovation-Report of the Expert Group on the State of Art in Europe on Responsible Research and Innovation. Luxembourg: European Commission.

European Commission (2020). Responsible Research and Innovation. Available online at: https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/horizon2020/en/h2020-section/responsible-research-innovation (accessed July 10, 2020).

Feldberg, H. R. (2011). S’more then Just Fun and Games: Teachers’ Perceptions on the Educational Value of Camp Programs for School Groups. Master’s thesis, University of Waterloo, Waterloo.

Feucht, F. C., Lunn Brownlee, J., and Schraw, G. (2017). Moving beyond reflection: reflexivity and epistemic cognition in teaching and teacher education. Educ. Psychol. 52, 234–241. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2017.1350180

Fine, G., and Corte, U. (2017). Group pleasures: collaborative commitments, shared narrative, and the sociology of fun. Sociol. Theory 35, 64–86. doi: 10.1177/0735275117692836

Fox, E., Jennifer, M., Proctor, C., and Ashley, M. (2013). “Happiness in the classroom,” in Oxford Handbook of Happiness, eds A. C. Ayers, I. Boniwell, and S. David (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Francis, N., and Kentel, J. (2008). The fun factor: adolescents’ self−regulated leisure activity and the implications for practitioners and researchers. Leisure/Loisir 32, 65–90. doi: 10.1080/14927713.2008.9651400

Freire, P. (1996). Pedagogia da autonomia: saberes necessários à prática educativa, 9 Edn. São Paulo: Paz e Terra.

Freire, P. (2000). Pedagogy of freedom: Ethics, democracy, and civic courage. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Freire, P. (2009). Pedagogia da esperança: um reencontro com a pedagogia do oprimido. 16. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra.

Fu, F. L., Su, R. C., and Yu, S. C. (2009). EGameFlow: a scale to measure learners’ enjoyment of e-learning games. Comput. Educ. 52, 101–112. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2008.07.004

Garn, A. C., and Cothran, D. J. (2006). The fun factor in physical education. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 25, 281–297. doi: 10.1123/jtpe.25.3.281

Glaveanu, V. P. (2011). Children and Creativity: a Most (Un)Likely Pair? Think. Skills Creat. 6, 122–131. doi: 10.1016/j.tsc.2011.03.002

Gortan, A., and Jereb, E. (2007). The dropout rate from e-learning courses and the satisfaction of students with e-learning. Organizacija 40.

Hardman, M., and Worthington, J. (2000). Educational Psychologists’ orientation to inclusion and assumptions about children’s learning. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 16, 349–360. doi: 10.1080/02667360020006417

Harmston, G. (2005). Sources of Enjoyment in Physical Activity Among Children and Adolescents. Los Angeles: California State University.

Higher Education Academy (HEA) (2015). Framework for Student Access, RETENTION, Attainment and Progression in Higher Education. Available online at: https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/system/files/downloads/studentaccess-retentionattainment-progression-in-he.pdf (accessed October 2020).

Hill, C. E., Thompson, B. J., and Williams, E. N. (1997). A guide to conducting consensual qualitative research. Couns. Psychol. 25, 517–572. doi: 10.1177/0011000097254001

Iten, N., and Petko, D. (2016). Learning with serious games: is fun playing the game a predictor of learning success? Br. J. Educ. Technol. 47, 151–163. doi: 10.1111/bjet.12226

Kimiecik, J. C., and Harris, A. T. (1996). What is enjoyment? A conceptual/definitional analysis with implications for sport and exercise psychology. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 18, 247–263. doi: 10.1123/jsep.20.3.247

Knight, S., Rienties, B., Littleton, K., Mitsui, M., Tempelaar, D., and Shah, C. (2017). The relationship of (perceived) epistemic cognition to interaction with resources on the internet. Comput. Human Behav. 73, 507–518. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2017.04.014

Lazzaro, N. (2009). “Why we play: affect and the fun of games,” in Human-computer interaction: Designing for diverse users and domains, eds A. Sears and J. A. Jacko (Boca Raton, FLA: CRC Press).

Lee, J., Zhang, Z., Song, H., and Huang, X. (2013). Effects of epistemological and pedagogical beliefs on the instructional practices of teachers: a Chinese Perspective. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 38, 119–146.

Lesser, L. M., Wall, A., Carver, R., Pearl, D. K., Martin, N., Kuiper, S., et al. (2013). Using fun in the statistics classroom: an exploratory study of college instructors’ hesitations and motivations. J. Stat. Educ. 21, 1–33.

McManus, I. C., and Furnham, A. (2010). “Fun, fun, fun”: types of fun, attitudes to fun, and their relation to personality and biographical factors. Psychology 1:159. doi: 10.4236/psych.2010.13021

Okada, A. (2020). Distance education: do students believe it should be fun? Available online at: https://www.open.edu/openlearn/education-development/learning/distance-education-do-students-believe-it-should-be-fun (accessed April 23, 2020).

Okada, A., and Sheehy, K. (2020). The value of fun in online learning: a study supported by responsible research and innovation and open data. Revista e-Curriculum 18, 319–343.

Okada, A., and Sherborne, T. (2018). Equipping the next generation for responsible research and innovation with open educational resources, open courses, open communities and open schooling: an impact case study in Brazil. J. Interact. Media Educ. 1, 1–15.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2010). Talis Technical Report. Available online at: http://www.oecd.org/education/school/44978960.pdf (accessed October 2020).

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OCED) (2013). Teaching and Learning International Survey TALIS 2013 Conceptual Framework. Available online at: http://www.oecd.org/edu/school/talis-2013-results.htm (accessed June 25, 2014).

Papert, S. (2002). Hard Fun. Bangor Daily News. Bangor. Available online at: http://www.papert.org/articles/HardFun.html (accessed July 10, 2020).

Prouty, D. (2002). Courage, compassion, creativity: project adventure at thirty. Zip Lines Voice Adventure Educ. 44, 6–12.

Richardson, J. T. E. (2013). Epistemological development in higher education. Educ. Res. Rev. 9, 191–206.

Rodriguez, L., and Cano, F. (2007). The learning approaches and epistemological beliefs of university students: a cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Stud. High. Educ. 32, 647–667. doi: 10.1080/03075070701573807

RRI-Tools (2016). Self-Reflection tool. Available online at: https://www.rri-tools.eu/self-reflection-tool (accessed July 10, 2020).

Sánchez-Franco, M. J., Peral-Peral, B., and Villarejo-Ramos, ÁF. (2014). Users’ intrinsic and extrinsic drivers to use a web-based educational environment. Comput. Educ. 74, 81–97. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2014.02.001

Schmidhuber, J. (2010). Formal theory of creativity, fun, and intrinsic motivation (1990–2010). IEEE Trans. Auton. Ment. Dev. 2, 230–247. doi: 10.1109/tamd.2010.2056368

Schommer, M. (1990). Effects of beliefs about the nature of knowledge oncomprehension. J. Educ. Psychol. 82, 498–504. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.82.3.498

Schon, D. (2015). Educating the reflective practitioner: toward a new design for teaching and learning in the professions (San Francisco: JosseyBass, 1987), and Ellen Schall,“learning to love the swamp: reshaping education for public service,” J. Policy Anal. Manage. 14:202. doi: 10.2307/3325150

Sheehy, K., and Budiyanto (2015). The pedagogic beliefs of Indonesian teachers in inclusive schools. Int. J. Disability Dev. Educ. 62, 469–485. doi: 10.1080/1034912X.2015.1061109

Sheehy, K., Budiyanto, Kaye, H., and Rofiah, K. (2019a). Indonesian teachers’ epistemological beliefs and inclusive education. J. Intellect. Disabil. 23, 39–56. doi: 10.1177/1744629517717613

Sheehy, K., Kasule, G. W., and Chamberlain, L. (2019b). Ugandan teachers epistemological beliefs and child-led research: implications for developing inclusive educational practice. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. (Early Access). doi: 10.1080/1034912X.2019.1699647

Tavakol, M., and Dennick, R. (2011). Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2, 53–55. doi: 10.5116/ijme.4dfb.8dfd

Tews, M. J., Jackson, K., Ramsay, C., and Michel, J. W. (2015). Fun in the college classroom: examining its nature and relationship with student engagement. Coll. Teach. 63, 16–26. doi: 10.1080/87567555.2014.972318

Tews, M. J., Michel, J. W., and Noe, R. A. (2017). Does fun promote learning? The relationship between fun in the workplace and informal learning. J. Vocat. Behav. 98, 46–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2016.09.006

Turner, C. (2018). Making lessons fun does not help children to learn, new report finds. Available online at: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/education/2018/11/14/making-lessons-fun-does-not-help-children-learn-new-report-finds/ (accessed November 14, 2018).

Ungar, M. (2007). Too Safe for their Own Good: How Risk and Responsibility Helpteens Thrive. Toronto, ON: McClelland & Stewart.

Virvou, M., Katsionis, G., and Manos, K. (2005). Combining software games with education: evaluation of its educational effectiveness. Educ. Technol. Soc. 8, 54–65.

von Schomberg, R. (2013). “A Vision of Responsible Research and Innovation,” in Responsible Innovation. Responsible Innovation: Managing the Responsible Emergence of Science and Innovation in Society, eds R. Owen, J. Bessant, and M. Heintz (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons), 51–74. doi: 10.1002/9781118551424.ch3

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Whitton, N., and Langan, M. (2018). Fun and games in higher education: an analysis of UK student perspectives. Teach. High. Educ. 24, 1000–1013. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2018.1541885

World Bank (2020). The COVID-19 Pandemic: Shocks to Education and Policy Responses. Washington, DC: World Bank. Available online at: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/33696 (accessed October 2020).

Keywords: COVID-19, online learning, fun, higher education, academic performance, epistemic views, responsible research and innovation, recommendations

Citation: Okada A and Sheehy K (2020) Factors and Recommendations to Support Students’ Enjoyment of Online Learning With Fun: A Mixed Method Study During COVID-19. Front. Educ. 5:584351. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.584351

Received: 17 July 2020; Accepted: 13 October 2020;

Published: 11 December 2020.

Edited by:

Leslie Michel Gauna, University of Houston–Clear Lake, United StatesReviewed by:

Khalil Gholami, University of Kurdistan, IranManpreet Kaur Bagga, Partap College of Education, India

Copyright © 2020 Okada and Sheehy. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alexandra Okada, ale.okada@open.ac.uk

Alexandra Okada

Alexandra Okada Kieron Sheehy

Kieron Sheehy