Economic Value of Parks via Human Mental Health: An Analytical Framework

- 1International Chair in Ecotourism Research, Griffith University, Gold Coast, QLD, Australia

- 2Menzies Health Institute Queensland, Griffith University, Gold Coast, QLD, Australia

Exposure to nature yields a wide range of mental health benefits. Improvements in mental health have substantial economic value, through: reduced mental healthcare costs; improved workplace productivity; and reduced costs of antisocial behavior, both public, and private. These economic gains represent an unquantified ecosystem service attributable to conservation. Since most individual people, and hence most politicians and policy-makers, care more about the private good of individual health than the public good of ecosystem and biodiversity conservation, calculating the economic value of nature via its contributions to human mental health could prove influential in achieving conservation goals. Here, we review relevant literature, establish a framework for these calculations, and identify immediate information gaps and research priorities. Current estimates rely on assumptions, but are similar in scale to those from tourism and recreation, which do influence policy.

Introduction

Conserving nature requires human actions and decisions, influenced by political systems. These are driven by human values: intrinsic, ethical, and emotional; and extrinsic, economic, and financial (Buckley, 2016). Economic values of conservation include: those which accrue to individuals whether or not they visit protected areas; and those which accrue only to individuals who use protected areas directly. The former have been analyzed largely as ecosystem services (Costanza et al., 1997; Balmford et al., 2002; De Groot et al., 2012; Fenichel et al., 2016), estimated at US$145 trillion worldwide in 2011 (Costanza et al., 2014). The latter include tourism and recreation (Balmford et al., 2009), estimated at US$600 billion globally (Balmford et al., 2015).

They also include human health benefits, both physiological and psychological, derived from individual use of nature, as opposed to public health gains from off-park ecosystem services such as clean air and water (Parks Canada, 2014; Redford et al., 2014; Romagosa et al., 2015; U.S. Department of the Interior, 2015; Yang et al., 2015). Here, we address the individual direct-use psychological health improvements. We propose that parks have an economic value attributable to visitors' mental health improvements. This is additional to intrinsic values, ecosystem services, and physical health improvements from exercise. Here, we construct an analytical framework to quantify this economic value; review relevant data to identify critical gaps; and propose future research to improve relevant economic estimates.

Practical conservation operates within multiple scientific and social contexts. From a scientific perspective, the role of intact biodiversity in maintaining ecosystem function operates independently of human perceptions (Wardle et al., 2011; Naeem et al., 2012; Hautier et al., 2015; Isbell et al., 2015). From a social perspective, conservation is embedded within human value systems, of which utilitarian values such as economic measures are only one component (Perrings et al., 2011; Dirzo et al., 2014). Economic valuations can be reached either through market processes, or outside them. They exert considerable influence on political decisions, notably allocation of land and water between competing uses (Morrison, 2015; Newbold et al., 2016).

Economic arguments for conservation are by no means the only arguments, but they are particularly powerful in political contexts (Biermann et al., 2012; Morrison, 2015; Buckley, 2016). Economists have calculated total economic value of conservation land use by aggregating economic values derived from different sources of value and mechanisms of valuation. We recognize the limitations of such approaches, but since they are indeed in common use, we argue that they should include values associated with human mental health.

Analytical Framework and Data Sources

Overall Approach

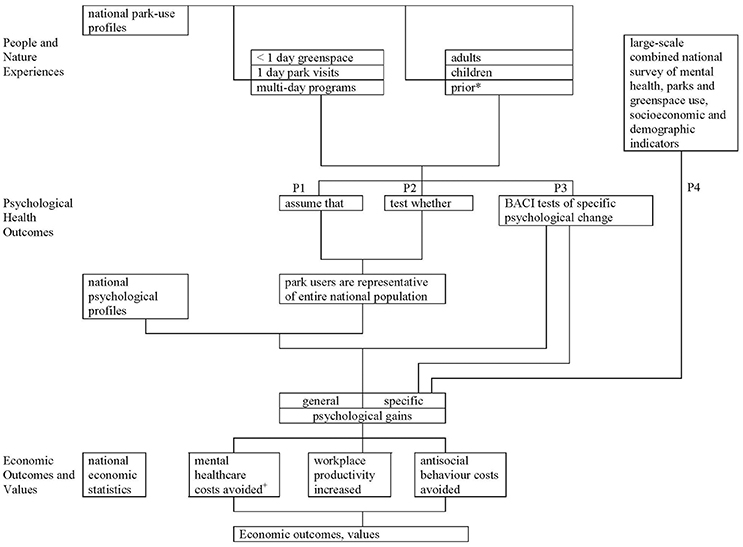

We propose a three-step analytical framework. The first is to quantify types of park users and park uses in a manageably small number of categories. The second is to quantify proportional changes in mental health parameters, for different categories of people and experiences. The third step quantifies economic values of mental health outcomes, using national economic statistics for public health. One key issue is estimating the degree to which parks users are representative of national populations. Our framework proposes four alternative pathways to address this. The calculation thus requires three datasets: park use patterns, mental health outcomes, and economic values, respectively. In contrast to the “metro nature” focus of Wolf et al. (2015), our focus here is on parks and other greenspace areas sufficiently large and undisturbed to be significant for conservation.

People and Nature Experiences

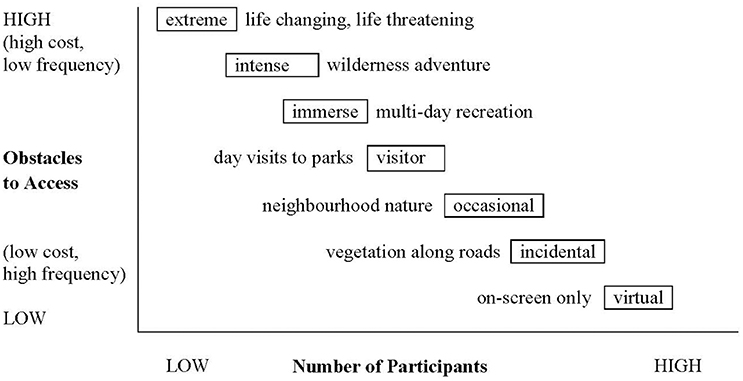

Park users and uses may be grouped by type and duration of nature exposure, and individual characteristics. Park experiences may be brief or extended, once-off or repeated, irregular or routine, group or solo, guided or unguided, motorized or unmotorized, individual or commercial. Different activities and experiences are available to different individuals, depending on age, physical capabilities, location, and finance. Some park-based activities also include exercise and social components; others rely solely on immersion and contemplation. Experiences of different types and intensities commonly involve different numbers of participants (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Broad-scale schematic relationship between intensity of experience and number of participants. Individual experiences may differ, e.g., adventure activities in neighborhood nature or urban greenspace.

For practical purposes, we can group park experiences into three broad categories: (i) brief visits to natural environments in residential areas, variously known as neighborhood nature, metro nature, or urban greenspace; (ii) single-day visits to parks and other public lands allocated for conservation and/or recreation; and (iii) multi-day programs. These are shown in Figure 1 as neighborhood nature, park visitors, and immersive multi-day. The multi-day category includes: (a) repeated activities in the same general area, part of organized programs; (b) independent multi-day nature-based activities, such as family camping trips; and (c) organized nature-based experiences, such as outdoor education and commercial nature-based tourism. Mental health research also includes both more and less intensive nature exposures than these three categories (Figure 1). Individuals have different patterns and profiles of nature experience and exposure, including different types and categories at different times and frequencies (Wolf et al., 2015). This is a simple classification to construct a practical framework.

Natural areas include public parks and wilderness, forests and rangelands, foreshores, and urban greenspace. Data on use and visitation for parks and reserves are available for some countries only (Balmford et al., 2009, 2015), and the degree of detail differs greatly between and within nations. Park use varies with attractions, notably biodiversity (Stevens et al., 2014; Siikamäki et al., 2015; proximity and access (Bancroft et al., 2015; Rossi et al., 2015), and wealth (Poudyal et al., 2013). Use of greenspace varies with many local factors (Jones et al., 2009; Lin et al., 2014; McCormack et al., 2014; Veitch et al., 2015). In some cities, these are incorporated in urban planning (Gidlöf-Gunnarsson and Öhrström, 2007; Villeneuve et al., 2012; Alcock et al., 2014; Francis et al., 2015; Giles-Corti et al., 2015; Ulmer et al., 2016).

Urban greenspace, “metro nature,” has an economic value attributable to its many parallel and complementary contributions to environmental health (Wolf and Robbins, 2015), including contributions to human physical and mental health over the entire life course (Wolf et al., 2015).

Despite the political significance of economic valuation, however, there has been no framework for financial valuation of nature through human mental health specifically (Wolf and Robbins, 2015). Here, therefore, we review and integrate relevant research, to construct such a framework.

Mental Health Outcomes

Improvements in mental health and happiness from experiences in nature have been documented widely over the past three decades (Wilson, 1984; Kaplan and Kaplan, 1989; Hartig et al., 1991, 2011, 2014; Ryan et al., 2010; Bailey and Fernando, 2012; Cervinka et al., 2012; Keniger et al., 2013; MacKerron and Mourato, 2013; Russell et al., 2013; Capaldi et al., 2014; Gilovich et al., 2014; James et al., 2015; Sandifer et al., 2015). Even adopting the simplest of these approaches (P1), quantifying mental health outcomes derived from exposure to nature is far from straightforward (Mayer et al., 2008; Bowler, 2010; Hartig et al., 2011, 2014; Thompson Coon et al., 2011; Keniger et al., 2013; Russell et al., 2013; Korpela et al., 2014; Kuo, 2015; Triguero-Mas et al., 2015).

We propose four parallel pathways to estimating mental health outcomes, summarized in Figure 2. The first two pathways (P1, P2 in Figure 2) rely on existing literature to quantify proportional mental health changes for the general population, and either assume (P1) or test whether (P2) park users are psychologically representative of national populations as a whole. The third pathway (P3) tests experimentally for specific psychological or mental health changes associated with park use, for particular categories of individuals and experiences. The fourth pathway (P4), the most comprehensive and reliable, involves large-scale random sampling of entire national populations to determine simultaneously the mental health parameters, park use patterns, and sociodemographic characteristics, for the same individuals at the same time.

Figure 2. Steps, pathways and information requirements to calculate economic value of parks attributable to improved human mental health.

Exposure to and experience of nature differs substantially between climates and cultures. In Scandinavian nations, concepts such as friluftsliv, open-air life, are in common use as part of national culture. In Japan and Korea, there is a widespread practice known as shinrin-yoku, “forest bathing,” as a deliberate measure to improve health (Li, 2010; Shin et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2011; Li et al., 2011; Morita et al., 2011; Craig et al., 2016). In China, there is a longstanding historical precedent for the philosophy of tian ren he yi, harmony between people and nature—even if, as in other nations, this may not be practiced in economic development. In many temperate English and Spanish-speaking nations, many urban residents may see nature principally as an outdoor playground, a place to practice outdoor sports or to get a short “nature fix.” In some Western nations, the use of “green prescriptions” has recently become an established part of medical practice (Swinburn et al., 1998; Maller et al., 2006; Townsend, 2006; Seltenrich, 2015; Ulmer et al., 2016). However, improvements are not universal (Saw et al., 2015; Townsend et al., 2015), and have rarely been quantified in ways which are generalizable, especially in terms of economic benefits to broad population groups.

The principal types of mental health outcomes reported in previous studies include: improved attention (Tennessen and Cimprich, 1995; Faber and Kuo, 2011); changed attitudes (Weinstein et al., 2009); improved cognition (Berman et al., 2008, 2012; Bratman et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2014; Zedelius and Schooler, 2015); reduced levels of stress, anxiety, and depression (Nutsford et al., 2013; Bratman et al., 2015); reduced use of antidepressants (Hartig et al., 2007; Taylor et al., 2015); improved recovery from stress (Bodin and Hartig, 2001); general improvements in mental health (Nielsen and Hansen, 2007; O'Campo et al., 2009; Bratman et al., 2012; Pearson and Craig, 2014); improved sleep (Grigsby-Toussaint et al., 2015); and improved life satisfaction (García-Mainar et al., 2015). These outcomes are not mutually exclusive: different individuals may experience multiple outcomes simultaneously (Hartig et al., 2011).

Mental health outcomes are reported for both adults and children (Dadvand et al., 2014, 2015; Wu et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2014), and for both men and women (Teas et al., 2007). Improvements derived from recreation and tourism have received particular attention (Kühnel and Sonnentag, 2011; Dolnicar et al., 2012; Chen and Petrick, 2013; Bimonte and Faralla, 2015; Coghlan, 2015; Zuo et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2016; Uysal et al., 2016). Mental health improvements are commonly coupled with physical and physiological gains (Pretty et al., 2005, 2007; Hughes et al., 2013; Astell-Burt et al., 2014; Haluza et al., 2014); but few studies to date have distinguished these mechanisms experimentally (Mitchell, 2013; Pasanen et al., 2014; Sandifer et al., 2015). Equally, few have considered the complex patterns of nature exposure which individuals experience in practice (Hartig et al., 2011).

In particular, mental health outcomes are dose-dependent (Barton and Pretty, 2010; Shanahan et al., 2015); but for exposure to nature, dose and response are both difficult to quantify (Hartig et al., 2014). Even relatively low-key exposure to nature in urban greenspace can generate measurable changes (Groenewegen et al., 2006, 2012; Maas et al., 2006; Bowler et al., 2010; Lee and Maheswaran, 2011; Lachowycz and Jones, 2013; Nutsford et al., 2013; Astell-Burt et al., 2014; Carter and Horwitz, 2014; Krekel et al., 2016). In at least some cases, this seems to apply especially if these areas are relatively high in biodiversity (Fuller et al., 2007; Thompson et al., 2012). Indeed, even views of nature from an office or hospital window can yield some improvements (Ulrich, 1984; Kaplan, 2001; Lee et al., 2015). More intense and extended nature experiences generate greater changes, but it is not yet clear whether the marginal returns increase or diminish, nor how different individuals may be affected by more complex patterns in nature exposure.

Economic Values

The third step (Figure 2) involves the estimation of economic values of mental health outcomes through multiple parallel additive pathways. As noted earlier, these are related respectively to: avoided costs of mental healthcare and treatment; improved workplace productivity; and avoided costs of antisocial behaviors, both public (e.g., vandalism) and private (e.g., domestic violence). Each of these mechanisms or pathways may be applied either for: overall general measures of mental health and wellbeing; broad categories such as mood and anxiety (ISCA/CEBR, 2015); or specific mental health parameters, if data are available.

Improvements in psychological health, and consequent economic gains, are dependent on the demographic, socioeconomic, and psychological characteristics of the individuals involved. As summarized above, recent research has demonstrated positive associations between individual subjective health evaluations and regular exposure to nature, but there are three caveats. Firstly, many of these studies are based on individuals who have purposefully chosen to exercise in parks or other greenspace, and who may not be representative of national populations as a whole. Secondly, there may be less opportunity for improvement for those individuals whose psychological health is functionally normal, than for those where it is not, and we do not currently know the prior mental health status of parks and greenspace users, or the degree to which current mental health profiles at population level may reflect existing patterns in park use. Thirdly, some psychological health conditions may respond much more readily than others, to nature-based prevention or treatment options. For practical purposes in calculating economic values, therefore, we can usefully differentiate three broad groups: healthy adults; healthy children; and individuals with known prior mental health conditions. Again, this is a simplification in order to construct a practical analytical framework.

Reductions in relevant mental healthcare costs have been estimated, at coarse scale, in a number of countries (Medibank Private, 2008; Myers and Patz, 2009; Myers et al., 2013; McKenzie et al., 2013; Australian Medical Association, 2014; National Heart Foundation of Australia, 2014; Hosie et al., 2015; ISCA/CEBR, 2015; Lambert et al., 2015). Improvements in workplace productivity (Korpela and Kinnunen, 2010; Ghermandi, 2015) may also include extensions to working life through reduced early mortality (Halonen et al., 2015), and reductions in youth unemployment payments (Hosie et al., 2015). Reductions in antisocial behavior for children and young adults carry forward into working life (Scott et al., 2001; D'Amico et al., 2014). Relevant statistics for each of these sources are available at national or subnational scale for some countries, but not others.

No country yet has all the data needed to calculate the economic value of its parks via human mental health, via any of the pathways outlined in Figure 2. Until the additional research identified here is undertaken, we can make only the broadest order-of-magnitudes estimates. Such estimates are large enough to be significant politically, indicating that additional research to provide accurate figures will indeed be worthwhile. For example, ~75% of the Australian population of ~24 million visit public national parks at least once each year, and 90% visit public urban greenspace (Veal, 2007; Zuo et al., 2015). Each year, >20% of Australians experience mental health problems, and 8% use mental health services (Whiteford et al., 2014; Hosie et al., 2015). Current costs of poor mental health in Australia are estimated at over AUD 200 billion (US$150 billion) annually (Medibank Private, 2008, 2013; Lancy and Gruen, 2013; Wade, 2016).

We can compare these figures with corresponding data from tourism and recreation, which form one major consideration in parks policy. Tourism in Australia is worth around AUD 93 billion p.a., of which around AUD 23 billion is broadly nature-based, and perhaps AUD 8–10 billion is derived from parks (Hooper and van Zyl, 2011; Balmford et al., 2015; Tourism Research Australia, 2015; Buckley, 2004, 2009). If conservation policy and parks agency budgets reflect the economic importance of tourism and recreation, therefore, then the same should surely apply to the economic value of mental health, happiness, and wellbeing.

Conclusions

In the longer term, human survival depends far more fundamentally on the health of ecosystems than the health of individual humans. In the short term, however, those individual humans value their own health and happiness much more highly than the natural environment, and government budget allocations for public health are far higher than those for conservation. It is for this reason that parks agencies and conservation organizations promote recreation and tourism in protected areas, as a mechanism to gain financial and political support.

Most individual people, and government economists, value recreational opportunities and associated expenditure more than the broader public good of conservation. The same applies even more strongly for human health, which individuals value highly, and which attracts a far larger total budget allocation through private insurance and public health programs, than the budgets provided for parks agencies and greenspace planning. The framework provided here, and summarized in Figure 2, could be used to calculate financial gains from the mental health benefits of conservation, accruing specifically to health insurers, employers, and to taxpayer-funded health care systems.

New empirical data, however, are required before this framework can be applied. Most critically, we need information on the mental health profile of park users; and on the mental health outcomes, for different individuals, from different patterns in short and long-term nature exposure at low and high intensities, over their entire life course. To obtain finer-scale calibration, such research could also include: nature experiences with higher or lower biodiversity; differences between park visitors with different cultural backgrounds; the benefits of volunteer or stewardship roles, as compared to leisure and tourism; and the relative durability of benefits derived from occasional or frequent visits, respectively. From a public health perspective, these could be used to construct optimal program of experience, from the nearby and familiar, to the distant and wild.

If we can quantify the links from nature to human mental health, and design mechanisms to maximize those links, we will create a new and powerful tool in favor of conservation. This requires not only the broad framework presented here, but the additional quantitative data outlined above, to demonstrate the effectiveness of nature-based experiences for individual psychological health, the financial gains for employers and health insurers, and the large-scale economic significance for public health policy.

Author Contributions

RB, PB: Devised the research, conducted the review, wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Australian Medical Association (2014). AMA Position Statement. Canberra, ACT: Australian Medical Association.

Alcock, I., White, M. P., Wheeler, B. W., Fleming, L. E., and Depledge, M. H. (2014). Longitudinal effects on mental health of moving to greener and less green urban areas. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 1247–1255. doi: 10.1021/es403688w

Astell-Burt, T., Mitchell, R., and Hartig, T. (2014). The association between green space and mental health varies across the lifecourse. A longitudinal study. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 68, 578–583. doi: 10.1136/jech-2013-203767

Bailey, A. W., and Fernando, I. K. (2012). Routine and project-based leisure, happiness, and meaning in life. J. Leis. Res. 44, 139–154.

Balmford, A., Beresford, J., Green, J., Naidoo, R., Walpole, M., and Manica, A. (2009). A global perspective on trends in nature-based tourism. PLoS Biol. 7:e1000144. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000144

Balmford, A., Bruner, A., Cooper, P., Costanza, R., Farber, S., Green, R. E., et al. (2002). Economic reasons for conserving wild nature. Science 297, 950–953. doi: 10.1126/science.1073947

Balmford, A., Green, J. M., Anderson, M., Beresford, J., Huang, C., Naidoo, R., et al. (2015). Walk on the wild side: estimating the global magnitude of visits to protected areas. PLoS Biol. 13:e1002074. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002074

Bancroft, C., Joshi, S., Rundle, A., Hutson, M., Chong, C., Weiss, C. C., et al. (2015). Association of proximity and density of parks and objectively measured physical activity in the United States: a systematic review. Soc. Sci. Med. 138, 22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.05.034

Barton, J., and Pretty, J. (2010). What is the best dose of nature and green exercise for improving mental health? A multi-study analysis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 44, 3947–3955. doi: 10.1021/es903183r

Berman, M. G., Jonides, J., and Kaplan, S. (2008). The cognitive benefits of interacting with nature. Psychol. Sci. 19, 1207–1212. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02225.x

Berman, M. G., Kross, E., Krpan, K. M., Askren, M. K., Burson, A., Deldin, P. J., et al. (2012). Interacting with nature improves cognition and affect for individuals with depression. J. Affect. Disord. 140, 300–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.03.012

Biermann, F., Abbott, K., Andresen, S., Bäckstrand, K., Bernstein, S., Betsill, M. M., et al. (2012). Navigating the Anthropocene: improving earth system governance. Science 335, 1306–1307. doi: 10.1126/science.1217255

Bimonte, S., and Faralla, V. (2015). Happiness and outdoor vacations: appreciative versus consumptive tourists. J. Travel Res. 54, 179–192. doi: 10.1177/0047287513513171

Bodin, M., and Hartig, T. (2001). Does the outdoor environment matter for psychological restoration gained through running? Psychol. Sport Exerc. 4, 141–153. doi: 10.1016/S1469-0292(01)00038-3

Bowler, D. (2010). The importance of nature for health: is there a specific benefit of contact with green space? Systematic review. Collab. Environ. Evid. 40, 57.

Bowler, D. E., Buyung-Ali, L. M., Knight, T. M., and Pullin, A. S. (2010). A systematic review of evidence for the added benefits to health of exposure to natural environments. BMC Public Health 10:456. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-456

Bratman, G. N., Hamilton, J. P., and Daily, G. C. (2012). The impacts of nature experience on human cognitive function and mental health. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1249, 118–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06400.x

Bratman, G. N., Hamilton, J. P., Hahn, K. S., Daily, G. C., and Gross, J. J. (2015). Nature experience reduces rumination and subgenual prefrontal cortex activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 8567–8572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1510459112

Buckley, R. (2004). Ecotourism land tenure and enterprise ownership: Australian case study. J. Ecotourism 3, 208–213. doi: 10.1080/14664200508668433

Buckley, R. (2016). Triage approaches send adverse political signals for conservation. Front. Ecol. Evol. 4:39. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2016.00039

Capaldi, C. A., Dopko, R. L., and Zelenski, J. M. (2014). The relationship between nature connectedness and happiness: a meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 5:976. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00976

Carter, M., and Horwitz, P. (2014). Beyond proximity: the importance of green space useability to self-reported health. Ecohealth 11, 322–332. doi: 10.1007/s10393-014-0952-9

Cervinka, R., Röderer, K., and Hefler, E. (2012). Are nature lovers happy? On various indicators of well-being and connectedness with nature. J. Health Psychol. 17, 379–388. doi: 10.1177/1359105311416873

Chen, C. C., and Petrick, J. F. (2013). Health and wellness benefits of travel experiences: a literature review. J. Travel Res. 52, 709–719. doi: 10.1177/0047287513496477

Chen, C. C., Petrick, J. F., and Shahvali, M. (2016). Tourism experiences as a stress reliever: examining the effects of tourism recovery experiences on life satisfaction. J. Travel Res. 55, 150–160. doi: 10.1177/0047287514546223

Coghlan, A. (2015). Tourism and health: using positive psychology principles to maximise participants' wellbeing outcomes–a design concept for charity challenge tourism. J. Sustain. Tourism 23, 382–400. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2014.986489

Costanza, R., Arge, D., and Groot, D. (1997). The value of the world's ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature 387, 235–260. doi: 10.1038/387253a0

Costanza, R., de Groot, R., Sutton, P., van der Ploeg, S., Anderson, S. J., da Kubiszewski, I., et al. (2014). Changes in the global value of ecosystem services. Glob. Environ. Change 26, 152–158. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.04.002

Craig, J. M., Logan, A. C., and Prescott, S. L. (2016). Natural environments, nature relatedness and the ecological theater: connecting satellites and sequencing to shinrin-yoku. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 63, 1. doi: 10.1186/s40101-016-0083-9

D'Amico, F., Knapp, M., Beecham, J., Sandberg, S., Taylor, E., and Sayal, K. (2014). Use of services and associated costs for young adults with childhood hyperactivity/conduct problems: 20-year follow-up. Br. J. Psychiatry 204, 441–447. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.131367

Dadvand, P., Nieuwenhuijsen, M. J., Esnaola, M., Forns, J., Basagaña, X., Alvarez-Pedrerol, M., et al. (2015). Green spaces and cognitive development in primary schoolchildren. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 7937–7942. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1503402112

Dadvand, P., Villanueva, C. M., Font-Ribera, L., Martinez, D., Basagaña, X., Belmonte, J., et al. (2014). Risks and benefits of green spaces for children: a cross-sectional study of associations with sedentary behavior, obesity, asthma, and allergy. Environ. Health Perspect. 122, 1329–1335. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1308038

De Groot, R., Brander, L., van der Ploeg, S., Costanza, R., Bernard, F., Braat, L., et al. (2012). Global estimates of the value of ecosystems and their services in monetary units. Ecosystem Serv. 1, 50–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2012.07.005

Dirzo, R., Young, H. S., Galetti, M., Ceballos, G., Isaac, N. J., and Collen, B. (2014). Defaunation in the anthropocene. Science 345, 401–406. doi: 10.1126/science.1251817

Dolnicar, S., Yanamandram, V., and Cliff, K. (2012). Ann. Tourism Res. 39, 59–83. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2011.04.015

Faber, T. A., and Kuo, F. E. M. (2011). Could exposure to everyday green spaces help treat ADHD? Evidence from children's play settings. Appl. Psychol. Health Well Being 3, 281–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-0854.2011.01052.x

Fenichel, E. P., Abbott, J. K., Bayham, J., Boone, W., Haacker, E. M., and Pfeiffer, L. (2016). Measuring the value of groundwater and other forms of natural capital. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 2382–2387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1513779113

Francis, J., Giles-Corti, B., Wood, L., and Knuiman, M. (2015). Neighbourhood influences on mental health in master planned estates: a qualitative study of resident perspectives. Health Promot. J. Aust. 25, 186–192. doi: 10.1071/HE14036

Fuller, R. A., Irvine, K. N., Devine-Wright, P., Warren, P. H., and Gaston, K. J. (2007). Psychological benefits of greenspace increase with biodiversity. Biol. Lett. 3, 390–394. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2007.0149

García-Mainar, I., Montuenga, V. M., and Navarro-Paniagua, M. (2015). Workplace environmental conditions and life satisfaction in Spain. Ecol. Econ. 119, 136–146. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.08.017

Ghermandi, A. (2015). Benefits of coastal recreation in Europe: identifying trade-offs and priority regions for sustainable management. J. Environ. Manag. 152, 218–229. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.01.047

Gidlöf-Gunnarsson, A., and Öhrström, E. (2007). Noise and well-being in urban residential environments: the potential role of perceived availability to nearby green areas. Landsc. Urban Plan. 83, 115–126. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2007.03.003

Giles-Corti, B., Sallis, J. F., Sugiyama, T., Frank, L. D., Lowe, M., and Owen, N. (2015). Translating active living research into policy and practice: one important pathway to chronic disease prevention. J. Public Health Policy 36, 231–243. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2014.53

Gilovich, T., Kumar, A., and Jampol, L. (2014). A wonderful life: experiential consumption and the pursuit of happiness. J. Consum. Psychol. 25, 138–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jcps.2014.08.004

Grigsby-Toussaint, D. S., Turi, K. N., Krupa, M., Williams, N. J., Pandi-Perumal, S. R., and Jean-Louis, G. (2015). Sleep insufficiency and the natural environment: results from the US behavioral risk factor surveillance system survey. Prev. Med. 78, 78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.07.011

Groenewegen, P. P., Van den Berg, A. E., De Vries, S., and Verheij, R. A. (2006). Vitamin G: effects of green space on health, well-being, and social safety. BMC Public Health 6:149. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-149

Groenewegen, P. P., van den Berg, A. E., Maas, J., Verheij, R. A., and de Vries, S. (2012). Is a green residential environment better for health? If so, why? Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 102, 996–1003. doi: 10.1080/00045608.2012.674899

Halonen, J. I., Hansell, A. L., Gulliver, J., Morley, D., Blangiardo, M., Fecht, D., et al. (2015). Road traffic noise is associated with increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality and all-cause mortality in London. Eur. Heart J. 36, 2653–2661. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv216

Haluza, D., Schönbauer, R., and Cervinka, R. (2014). Green perspectives for public health: A narrative review on the physiological effects of experiencing outdoor nature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 11, 5445–5461. doi: 10.3390/ijerph110505445

Hartig, T., Catalano, R., and Ong, M. (2007). Cold summer weather, constrained restoration, and the use of antidepressants in Sweden. J. Environ. Psychol. 27, 107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2007.02.002

Hartig, T., Mang, M., and Evans, G. W. (1991). Restorative effects of natural environment experiences. Environ. Behav. 23, 3–26. doi: 10.1177/0013916591231001

Hartig, T., Mitchell, R., De Vries, S., and Frumkin, H. (2014). Nature and health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 35, 207–228. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182443

Hartig, T., van den Berg, A. E., Hagerhall, C. M., Tomalak, M., Bauer, N., Hansmann, R., et al. (2011). “Health benefits of nature experience: psychological, social and cultural processes,” in Forests, Trees and Human Health, eds K. Nilsson, M. Sangster, C. Gallis, T. Hartig, S. De Vries, K. Seeland, and J. Schipperijn (New York, NY: Springer), 127–168.

Hautier, Y., Tilman, D., Isbell, F., Seabloom, E. W., Borer, E. T., and Reich, P. B. (2015). Anthropogenic environmental changes affect ecosystem stability via biodiversity. Science 348, 336–340. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa1788

Hooper, K., and van Zyl, M. (2011). Australia's Tourism Industry. Canberra, ACT: Reserve Bank of Australia.

Hosie, A., Vogl, G., Carden, J., Hoddinott, J., and Lim, S. (2015). A Way Forward: Equipping Australia's Mental Health System for the Next Generation. Canberra, ACT: ReachOut Australia.

Hughes, J., Pretty, J., and Macdonald, D. W. (2013). Nature as a source of health and well-being: is this an ecosystem service that could pay for conserving biodiversity?. Key Top. Conserv. Biol. 2, 143. doi: 10.1002/9781118520178.ch9

International, Sport and Culture Association, Centre for Economics and Business, Research. (2015). The Economic Cost of Physical Inactivity in Europe. London: ISCA/CEBR.

Isbell, F., Craven, D., Connolly, J., Loreau, M., Schmid, B., Beierkuhnlein, C., et al. (2015). Biodiversity increases the resistance of ecosystem productivity to climate extremes. Nature 526, 574–577. doi: 10.1038/nature15374

James, P., Banay, R. F., Hart, J. E., and Laden, F. (2015). A review of the health benefits of greenness. Curr. Epidemiol. Rep. 2, 131–142. doi: 10.1007/s40471-015-0043-7

Jones, A., Hillsdon, M., and Coombes, E. (2009). Greenspace access, use, and physical activity: understanding the effects of area deprivation. Prev. Med. 49, 500–505. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.10.012

Kaplan, R. (2001). The nature of the view from home: psychological benefits. Environ. Behav. 33, 507–542. doi: 10.1177/00139160121973115

Kaplan, R., and Kaplan, S. (1989). The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Keniger, L. E., Gaston, K. J., Irvine, K. N., and Fuller, R. A. (2013). What are the benefits of interacting with nature? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 10, 913–935. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10030913

Korpela, K., Borodulin, K., Neuvonen, M., Paronen, O., and Tyrväinen, L. (2014). Analyzing the mediators between nature-based outdoor recreation and emotional well-being. J. Environ. Psychol. 37, 1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2013.11.003

Korpela, K., and Kinnunen, U. (2010). How is leisure time interacting with nature related to the need for recovery from work demands? Testing multiple mediators. Leisure Sci. 33, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/01490400.2011.533103

Krekel, C., Kolbe, J., and Wüstemann, H. (2016). The greener, the happier? The effect of urban land use on residential well-being. Ecol. Econ. 121, 117–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.11.005

Kühnel, J., and Sonnentag, S. (2011). How long do you benefit from vacation? A closer look at the fade-out of vacation effects. J. Organ. Behav. 32, 125–143. doi: 10.1002/job.699

Kuo, M. (2015). How might contact with nature promote human health? Promising mechanisms and a possible central pathway. Front. Psychol. 6:1093. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01093

Lachowycz, K., and Jones, A. P. (2013). Towards a better understanding of the relationship between greenspace and health: development of a theoretical framework. Landsc. Urban Plan. 118, 62–69. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2012.10.012

Lambert, K. G., Nelson, R. J., Jovanovic, T., and Cerdá, M. (2015). Brains in the city: neurobiological effects of urbanization. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 58, 107–122. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.04.007

Lancy, A., and Gruen, N. (2013). Constructing the Herald/Age–Lateral economics index of Australia's Wellbeing. Aust. Econ. Rev. 46, 92–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8462.2013.12000.x

Lee, A. C. K., and Maheswaran, R. (2011). The health benefits of urban green spaces: a review of the evidence. J. Public Health 33, 212–222. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdq068

Lee, J., Park, B. J., Tsunetsugu, Y., Ohira, T., Kagawa, T., and Miyazaki, Y. (2011). Effect of forest bathing on physiological and psychological responses in young Japanese male subjects. Public Health 125, 93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2010.09.005

Lee, K. E., Williams, K. J., Sargent, L. D., Williams, N. S., and Johnson, K. A. (2015). 40-second green roof views sustain attention: the role of micro-breaks in attention restoration. J. Environ. Psychol. 42, 182–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2015.04.003

Li, Q. (2010). Effect of forest bathing trips on human immune function. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 15, 9–17. doi: 10.1007/s12199-008-0068-3

Li, Q., Otsuka, T., Kobayashi, M., Wakayama, Y., Inagaki, H., Katsumata, M., et al. (2011). Acute effects of walking in forest environments on cardiovascular and metabolic parameters. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 111, 2845–2853. doi: 10.1007/s00421-011-1918-z

Lin, B. B., Fuller, R. A., Bush, R., Gaston, K. J., and Shanahan, D. F. (2014). Opportunity or orientation? Who uses urban parks and why. PLoS ONE 9:e87422. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087422

Maas, J., Verheij, R. A., Groenewegen, P. P., de Vries, S., and Spreeuwenberg, P. (2006). Green space, urbanity, and health: how strong is the relation? J. Epidemiol. Community Health 60, 587–592. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.043125

MacKerron, G., and Mourato, S. (2013). Happiness is greater in natural environments. Glob. Environ. Change 23, 992–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.03.010

Maller, C., Townsend, M., Pryor, A., Brown, P., and St Leger, L. (2006). Healthy nature, healthy people: contact with nature as an upstream health promotion intervention for populations. Health Promot. Int. 21, 45–54. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dai032

Mayer, F. S., Frantz, C. M., Bruehlman-Senecal, E., and Dolliver, K. (2008). Why is nature beneficial? The role of connectedness to nature. Environ. Behav. 41, 607–643. doi: 10.1177/0013916508319745

McCormack, G. R., Rock, M., Swanson, K., Burton, L., and Massolo, A. (2014). Physical activity patterns in urban neighbourhood parks: insights from a multiple case study. BMC Public Health 14:962. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-962

McKenzie, K., Murray, A., and Booth, T. (2013). Do urban environments increase the risk of anxiety, depression and psychosis? An epidemiological study. J. Affect. Disord. 150, 1019–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.05.032

Medibank, Private (2013). The Case for Mental Health Reform in Australia: a Review of Expenditure and System Design. Canberra, ACT: Medibank Private.

Mitchell, R. (2013). Is physical activity in natural environments better for mental health than physical activity in other environments? Soc. Sci. Med. 91, 130–134. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.04.012

Morita, E., Imai, M., Okawa, M., Miyaura, T., and Miyazaki, S. (2011). A before and after comparison of the effects of forest walking on the sleep of a community-based sample of people with sleep complaints. Biopsychosoc. Med. 5:13. doi: 10.1186/1751-0759-5-13

Morrison, S. A. (2015). A framework for conservation in a human-dominated world. Conserv. Biol. 29, 960–964. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12432

Myers, S. S., Gaffikin, L., Golden, C. D., Ostfeld, R. S., Redford, K. H., Ricketts, T. H., et al. (2013). Human health impacts of ecosystem alteration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 18753–18760. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218656110

Myers, S. S., and Patz, J. A. (2009). Emerging threats to human health from global environmental change. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 34, 223–252. doi: 10.1146/annurev.environ.033108.102650

Naeem, S., Duffy, J. E., and Zavaleta, E. (2012). The functions of biological diversity in an age of extinction. Science 336, 1401–1406. doi: 10.1126/science.1215855

National Heart Foundation of Australia (2014). Blueprint for an Active Australia, 2nd Edn. Melbourne, VIC: National Heart Foundation of Australia.

Newbold, T., Hudson, L. N., Arnell, A. P., Contu, S., De Palma, A., Ferrier, S., et al. (2016). Has land use pushed terrestrial biodiversity beyond the planetary boundary?. Glob. Assess. Sci. 353, 288–291. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf2201

Nielsen, T. S., and Hansen, K. B. (2007). Do green areas affect health? Results from a Danish survey on the use of green areas and health indicators. Health Place 13, 839–850. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2007.02.001

Nutsford, D., Pearson, A., and Kingham, S. (2013). An ecological study investigating the association between access to urban green space and mental health. Public Health 127, 1005–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2013.08.016

O'Campo, P., Salmon, C., and Burke, J. (2009). Neighbourhoods and mental well-being: What are the pathways?. Health Place 15, 56–68. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.02.004

Parks Canada (2014). Connecting Canadians with Nature: An Investment in the Well-being of our Citizens. Ottawa, ON: Parks Canada.

Pasanen, T. P., Tyrväinen, L., and Korpela, K. M. (2014). The relationship between perceived health and physical activity indoors, outdoors in built environments, and outdoors in nature. Appl. Psychol. Health Well Being 6, 324–346. doi: 10.1111/aphw.12031

Pearson, D. G., and Craig, T. (2014). The great outdoors? Exploring the mental health benefits of natural environments. Front. Psychol. 5:1178. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01178

Perrings, C., Duraiappah, A., Larigauderie, A., and Mooney, H. (2011). The biodiversity and ecosystem services science-policy interface. Science 331, 1139–1140. doi: 10.1126/science.1202400

Poudyal, N. C., Paudel, B., and Tarrant, M. A. (2013). A time series analysis of the impact of recession on national park visitation in the United States. Tourism Manage. 35, 181–189. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2012.07.001

Pretty, J., Peacock, J., Hine, R., Sellens, M., South, N., and Griffin, M. (2007). Green exercise in the UK countryside: Effects on health and psychological well-being, and implications for policy and planning. J. Environ. Plan. Manage. 50, 211–231. doi: 10.1080/09640560601156466

Pretty, J., Peacock, J., Sellens, M., and Griffin, M. (2005). The mental and physical health outcomes of green exercise. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 15, 319–337. doi: 10.1080/09603120500155963

Redford, K. H., Myers, S. S., Ricketts, T. H., and Osofsky, S. A. (2014). Human health as a judicious conservation opportunity. Conserv. Biol. 28, 627–629. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12290

Romagosa, F., Eagles, P. F., and Lemieux, C. J. (2015). From the inside out to the outside in: Exploring the role of parks and protected areas as providers of human health and well-being. J. Outdoor Recreation Tourism 10, 70–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jort.2015.06.009

Rossi, S. D., Byrne, J. A., and Pickering, C. M. (2015). The role of distance in peri-urban national park use: Who visits them and how far do they travel? Appl. Geogr. 63, 77–88. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeog.2015.06.008

Russell, R., Guerry, A. D., Balvanera, P., Gould, R. K., Basurto, X., Chan, K. M., et al. (2013). Humans and nature: how knowing and experiencing nature affect well-being. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 38, 473–502. doi: 10.1146/annurev-environ-012312-110838

Ryan, R. M., Weinstein, N., Bernstein, J., Brown, K. W., Mistretta, L., and Gagne, M. (2010). Vitalizing effects of being outdoors and in nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 30, 159–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2009.10.009

Sandifer, P. A., Sutton-Grier, A. E., and Ward, B. P. (2015). Exploring connections among nature, biodiversity, ecosystem services, and human health and well-being: opportunities to enhance health and biodiversity conservation. Ecosystem Serv. 12, 1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2014.12.007

Saw, L. E., Lim, F. K., and Carrasco, L. R. (2015). The relationship between natural park usage and happiness does not hold in a tropical city-state. PLoS ONE 10:e0133781. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133781

Scott, S., Knapp, M., Henderson, J., and Maughan, B. (2001). Financial cost of social exclusion: follow up study of antisocial children into adulthood. Br. Med. J. 323:191. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7306.191

Seltenrich, N. (2015). Just what the doctor ordered: using parks to improve children's health. Environ. Health Perspect. 123:A254. doi: 10.1289/ehp.123-A254

Shanahan, D. F., Fuller, R. A., Bush, R., Lin, B. B., and Gaston, K. J. (2015). The health benefits of urban nature: how much do we need?. Bioscience 65, 476–485. doi: 10.1093/biosci/biv032

Shin, W. S., Yeoun, P. S., Yoo, R. W., and Shin, C. S. (2010). Forest experience and psychological health benefits. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 15, 38–47. doi: 10.1007/s12199-009-0114-9

Siikamäki, P., Kangas, K., Paasivaara, A., and Schroderus, S. (2015). Biodiversity attracts visitors to national parks. Biodivers. Conserv. 24, 2521–2534. doi: 10.1007/s10531-015-0941-5

Stevens, T. H., More, T. A., and Markowski-Lindsay, M. (2014). Declining national park visitation. J. Leis. Res. 46, 153–164.

Swinburn, B. A., Walter, L. G., Arroll, B., Tilyard, M. W., and Russell, D. G. (1998). The green prescription study: a randomized controlled trial of written exercise advice provided by general practitioners. Am. J. Public Health 88, 288–291. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.88.2.288

Taylor, M. S., Wheeler, B. W., White, M. P., Economou, T., and Osborne, N. J. (2015). Research note: urban street tree density and antidepressant prescription rates a cross-sectional study in London, UK. Landscape Urban Plan. 136, 174–179. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2014.12.005

Teas, J., Hurley, T., Ghumare, S., and Ogoussan, K. (2007). Walking outside improves mood for healthy postmenopausal women. Clin. Med. Insights.Oncol. 1, 35.

Tennessen, C. M., and Cimprich, B. (1995). Views to nature: effects on attention. J. Environ. Psychol. 15, 77–85. doi: 10.1016/0272-4944(95)90016-0

Thompson, C. W., Roe, J., Aspinall, P., Mitchell, R., Clow, A., and Miller, D. (2012). More green space is linked to less stress in deprived communities: evidence from salivary cortisol patterns. Landsc. Urban Plan. 105, 221–229. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2011.12.015

Thompson Coon, J., Boddy, K., Stein, K., Whear, R., Barton, J., and Depledge, M. H. (2011). Does participating in physical activity in outdoor natural environments have a greater effect on physical and mental wellbeing than physical activity indoors? A systematic review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 1761–1772. doi: 10.1021/es102947t

Townsend, M. (2006). Feel blue? Touch green! Participation in forest/woodland management as a treatment for depression. Urban Forestry Urban Greening 5, 111–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2006.02.001

Townsend, M., Henderson-Wilson, C., Warner, E., and Weiss, L. (2015). Healthy Parks Healthy People: The State of the Evidence. Melbourne, VIC: Parks Victoria and Deakin University.

Triguero-Mas, M., Dadvand, P., Cirach, M., Martínez, D., Medina, A., Mompart, A., et al. (2015). Natural outdoor environments and mental and physical health: relationships and mechanisms. Environ. Int. 77, 35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2015.01.012

Ulmer, J. M., Wolf, K. L., Backman, D. R., Tretheway, R. L., Blain, C. J., O'Neil-Dunne, J. P., et al. (2016). Multiple health benefits of urban tree canopy: the mounting evidence for a green prescription. Health Place 42, 54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.08.011

Ulrich, R. (1984). View through a window may influence recovery. Science 224, 224–225. doi: 10.1126/science.6143402

U.S. Department of the Interior (2015). Every Kid in a Park. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior.

Uysal, M., Sirgy, M. J., Woo, E., and Kim, H. L. (2016). Quality of life (QOL) and well-being research in tourism. Tourism Manag. 53, 244–261. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2015.07.013

Veitch, J., Carver, A., Abbott, G., Giles-Corti, B., Timperio, A., and Salmon, J. (2015). How active are people in metropolitan parks? An observational study of park visitation in Australia. BMC Public Health 15:6. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1960-6

Villeneuve, P. J., Jerrett, M., Su, J. G., Burnett, R. T., Chen, H., Wheeler, A. J., et al. (2012). A cohort study relating urban green space with mortality in Ontario, Canada. Environ. Res. 115, 51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2012.03.003

Wade, M. (2016). Available online at: http://www.smh.com.au/national/the-wellbeing-cost-of-mental-health-hits-200-billion-20160909-grcxxl.html (Accessed October 10, 2016).

Wardle, D. A., Bardgett, R. D., Callaway, R. M., and Van der Putten, W. H. (2011). Terrestrial ecosystem responses to species gains and losses. Science 332, 1273–1277. doi: 10.1126/science.1197479

Weinstein, N., Przybylski, A. K., and Ryan, R. M. (2009). Can nature make us more caring? Effects of immersion in nature on intrinsic aspirations and generosity. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 35, 1315–1329. doi: 10.1177/0146167209341649

Whiteford, H. A., Buckingham, W. J., Harris, M. G., Burgess, P. M., Pirkis, J. E., Barendregt, J. J., et al. (2014). Estimating treatment rates for mental disorders in Australia. Aust. Health Rev. 38, 80–85. doi: 10.1071/AH13142

Wolf, K. L., Measells, M. K., Grado, S. C., and Robbins, A. S. (2015). Economic values of metro nature health benefits: a life course approach. Urban Forest. Urban Green. 14, 694–701. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2015.06.009

Wolf, K. L., and Robbins, A. S. (2015). Metro nature, environmental health, and economic value. Environ. Health Perspect. 123, 390–398. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1408216

Wu, C. D., McNeely, E., Cedeno-Laurent, J. G., Pan, W. C., Adamkiewicz, G., Dominici, F., et al. (2014). Linking student performance in Massachusetts elementary schools with the greenness of school surroundings using remote sensing. PLoS ONE 9:e108548. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108548

Yang, W., Dietz, T., Kramer, D. B., Ouyang, Z., and Liu, J. (2015). An integrated approach to understanding the linkages between ecosystem services and human well-being. Ecosyst. Health Sustain. 1, 1–12. doi: 10.1890/EHS15-0001.1

Zedelius, C. M., and Schooler, J. W. (2015). Mind wandering Ahas versus mindful reasoning: alternative routes to creative solutions. Front. Psychol. 6:834. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00834

Zhang, W., Goodale, E., and Chen, J. (2014). How contact with nature affects children's biophilia, biophobia and conservation attitude in China. Biol. Conserv. 177, 109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2014.06.011

Keywords: conservation, policy, social-psychology, government-financing, ecosystem-services

Citation: Buckley RC and Brough P (2017) Economic Value of Parks via Human Mental Health: An Analytical Framework. Front. Ecol. Evol. 5:16. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2017.00016

Received: 15 March 2016; Accepted: 02 March 2017;

Published: 16 March 2017.

Edited by:

Mark A. Elgar, University of Melbourne, AustraliaReviewed by:

Terry Hartig, Uppsala University, SwedenKathleen L. Wolf, University of Washington, USA

Copyright © 2017 Buckley and Brough. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ralf C. Buckley, ralf.c.buckley@gmail.com; r.buckley@griffith.edu.au

Ralf C. Buckley

Ralf C. Buckley Paula Brough2

Paula Brough2