- 1Centre for Liver Research, National Institute of Health Research Birmingham Biomedical Research Centre, Institute of Immunology and Immunotherapy, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, United Kingdom

- 2Faculty of Health and Life Sciences, School of Life Sciences, Coventry University, Coventry, United Kingdom

- 3University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust, Birmingham, United Kingdom

Thymic-derived naturally occurring regulatory T cells (tTreg) are crucial for maintaining peripheral immune homeostasis. They play a crucial role in preventing autoimmunity and maintaining organ transplant without requiring immunosuppression. Cellular metabolism has recently emerged as an important regulator of adaptive immune cell balance between Treg and effector T cells. While the metabolic requirements of conventional T cells are increasingly understood, the role of Treg cellular metabolism is less clear. The continuous exposure of metabolites and nutrients to the human liver via the portal blood flow influences the lineage fitness, function, proliferation, migration, and survival of Treg cells. As cellular metabolism has an impact on its function, it is crucial to understand the metabolic pathways wiring in regulatory T cells. Currently, there are ongoing early phase clinical trials with polyclonal and antigen-specific good manufacturing practice (GMP) Treg therapy to treat autoimmune diseases and organ transplantation. Thus, enhancing immunometabolic pathways of Treg by translational approach with existing or new drugs would utilize Treg cells to their full potential for effective cellular therapy.

Regulatory T Cells and Peripheral Self-Tolerance

Regulatory T (Treg) cells are a subset of CD4+ T cells that maintain peripheral immune homeostasis by suppressing a range of untoward immune responses thus maintaining the balance between immune activation and tolerance (1). Sakaguchi and colleagues first reported Treg cells in 1995 via adoptive transfer studies, which demonstrated the subset of CD4+ T cells expressing the interleukin-2 (IL-2) receptor alpha chain, CD25, preventing autoimmune diseases (2) (Figure 1). Around 5–10% of CD4+ T cells are CD25+, they are able to maintain peripheral immunologic self-tolerance by suppressing self-reactive lymphocytes (1, 2). Subsequently, Seddiki (3) and Liu (4) reported that low level expression of the IL-7 receptor, CD127, inversely correlated with FoxP3 expression and Treg cell’s suppressive function due to the repressor function of FoxP3. FoxP3 is a master transcription factor and regulator of Treg phenotype and function (5). Mutations in the FoxP3 gene cause defective development of CD4+CD25+ Treg cells, leading to IPEX syndrome (immunodysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked genetic trait) (6). Lymphoproliferation and multiorgan autoimmunity in scurfy mutant mice is caused by the absence of FoxP3 (7). FoxP3 is regulated by conserved non-coding DNA sequences (CNS) 1–3. CNS2 is required for FoxP3 expression in the dividing Treg cell and CNS3 controls de novo Foxp3 expression and thymic Treg-cell differentiation (8). Therefore, Treg cells are currently defined as CD4+CD25highCD127low/−FoxP3+ cells.

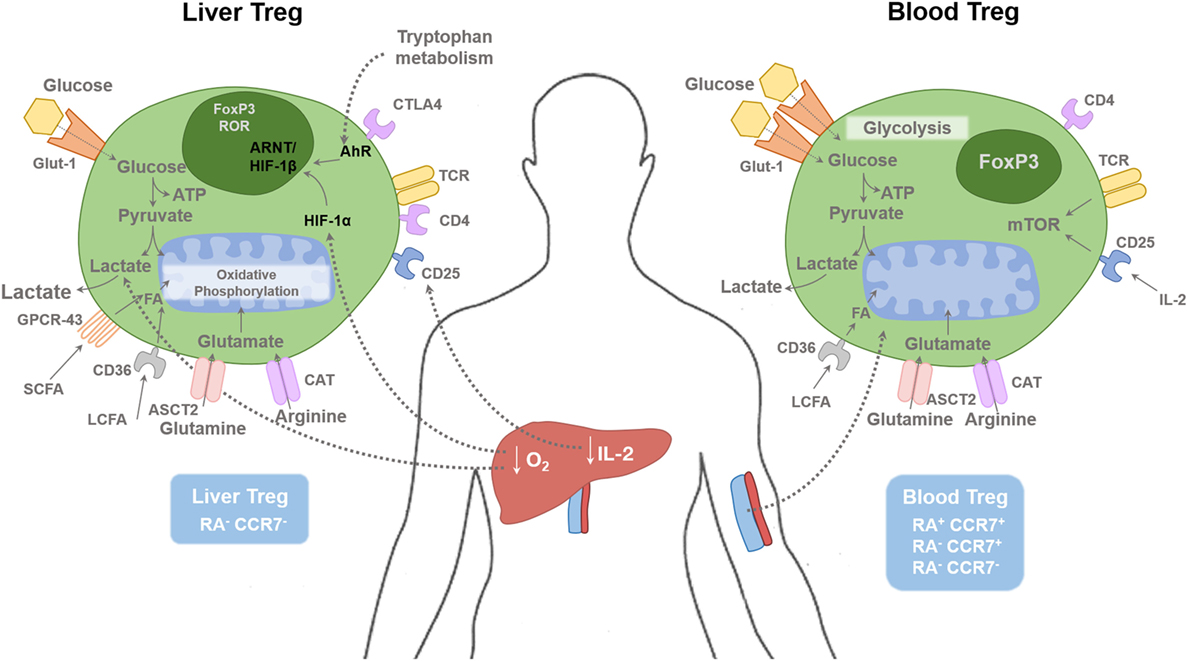

Figure 1. Regulatory T cells in tissue and blood compartments. The human liver is a hypoxic environment as the majority of blood flow is from the portal venous system. This leads to hypoxic induced factor 1-α (HIF-1α) activation, which subsequently enhances FoxP3 expression along with Th17 differentiation. Hypoxia leads to anaerobic glycolysis and extracellular lactic acid accumulation. Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) bind to the receptor GPCR43; long-chain fatty acids (LCFAs) bind to CD36, glutamine binds to ASCT2, and arginine binds to CAT2. Glucose transporter-1 (Glut-1) is poorly expressed on Treg cells compared with effector T cells. Liver Treg cells are mainly of an effector memory phenotype (RA−CCR7−). There is only minimal level of IL-2 present in the human liver compared with the blood, which restrict hepatic Treg function. Blood Treg-cell subsets are composed of effector memory (RA−CCR7−), central memory (RA−CCR7+), and naive (RA+CCR7+) phenotype. HIF-1α, Hypoxia-inducible factor 1α; HIF-1β, Hypoxia-inducible factor-1β; AhR, aryl hydrocarbon receptor; FA, Fatty acids; ARNT, Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Nuclear Translocator; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; SCFA, short chain fatty acid; LCFA, long chain fatty acid; ASCT2, Alanine, serine, cysteine-preferring transporter 2; CAT, Cationic amino acid transporter; GPCR, G protein–coupled receptor.

Treg cells are essential for maintaining peripheral tolerance by controlling autoreactive T cells, which escape negative selection in the thymus (9). They can be broadly divided into two types; thymic-derived Treg (tTreg) cells and peripheral Treg (pTreg) cells (10). Strong T cell receptor (TCR) signaling with CD28 co-stimulation, just below the threshold for negative selection, promotes tTreg lineage commitment in the thymus (11). pTreg cells are generated in the periphery from populations of mature T cells under certain antigenic stimulating conditions; persistent weak TCR stimulation along with IL-2, transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) or retinoic acid (RA) (12, 13). The DNA in tTregs is demethylated in the Treg-specific demethylated region (TSDR) in the FoxP3 enhancer, whereas the TSDR of pTregs is only partially demethylated (14). Although both tTreg and pTreg are difficult to distinguish phenotypically, both are thought to play an essential role in immune regulation (15), with tTreg cells controlling reactivity toward self-antigens and pTreg cells controlling responses to antigen exposure in the periphery. Treg cells require IL-2 to maintain their function and survival. Because Treg cells do not make IL-2, they are dependent on IL-2 derived from other T cells (16). Treg cells are highly sensitive to IL-2, due to their constitutively high expression of CD25 and amplified intracellular signal transduction downstream of the IL-2 receptor, phosphorylation of STAT5 to upregualte essential Treg functional gene such as CD25, FoxP3, and cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) (17). Treg cells can therefore compete with conventional T cells for IL-2 as a mechanism to prevent unwanted immune responses (17).

Treg conduct their suppressive function via multiple mechanisms throughout different compartments of the body. Treg are therefore also equipped with various functional markers. In the context of liver disease, they constitutively express CTLA-4 (16, 18, 19), ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase 1, CD39 (16, 20), and the intracellular immunosuppressive cytokine, IL-10 (16, 21).

Cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 is a target gene of FoxP3 (22), and activation of Treg results in upregulation of CTLA-4; its deficiency in mice leads to fatal lymphoproliferation and multiorgan lymphocyte infiltration (23, 24). CTLA-4 binds the ligands CD80 and CD86 on antigen-presenting cells (APCs) such as dendritic cells (DCs). Its mechanism has been reported as removal of these ligands from APC cell surface by trans-endocytosis, which subsequently prevents the effective activation of naïve CD4+ T cells by APCs (25). CTLA-4-CD80/CD86 binding leads to upregulation of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), which catabolizes tryptophan (Trp) into immunosuppressive kynurenines (26). CD39 on both human and murine Treg exert their function via generation of adenosine by the breakdown of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and other extracellular nucleotides, which then bind to adenosine 2A receptors expressed on effector T cells causing a rise in intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate, thus inhibiting proliferation of effector T cells (27).

Intrahepatic Microenvironment

The phenotype and function of Treg cells in circulatory and intrahepatic compartments is different as the intrahepatic microenvironment is hypoxic and enriched with cytokines and metabolic products (1) (Figure 1). Intrahepatic Treg cells respond to (i) engagement of the TCR with MHC Class II on APCs, (ii) the binding of CD28/CTLA-4 on cells with CD80/86 on APCs, and (iii) the influence of cytokines from APC for their activation, survival, and differentiation (28, 29). We reported that the intrahepatic microenvironment is highly enriched with the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-12 (16) from hepatic DCs but lacks the crucial Treg cell survival cytokine; IL-2 (19). With the recent advances in research into the metabolism of individual immune cell including T cells, it is now realized that differentiation, survival, and function of Treg cells depends not only on TCR, co-stimulatory and cytokine signals but also on other signals in the environment, specifically the local milieu of oxygen, metabolites, and catabolites (30).

Metabolic Influence on Plasticity, Function, Survival, and Migration of Treg Cells

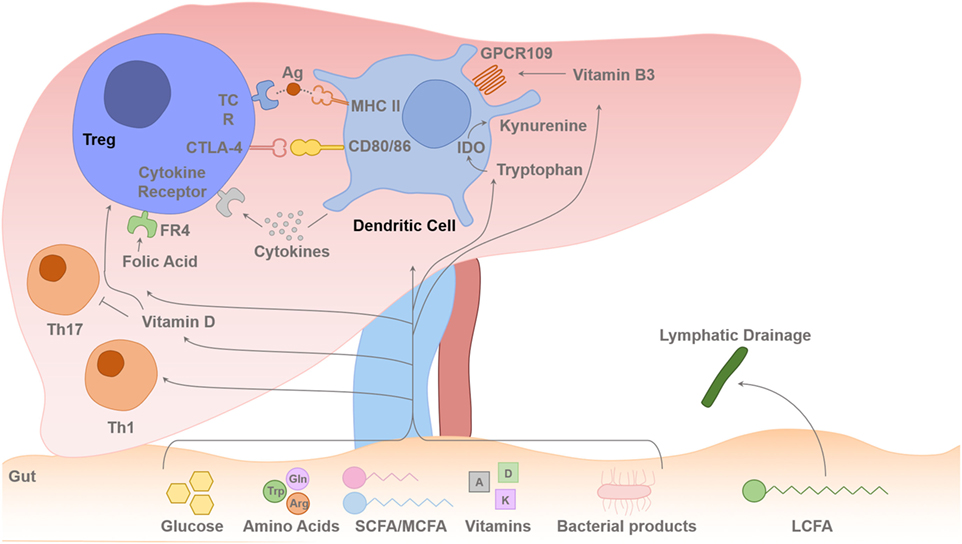

The human liver is uniquely situated to receive a blood supply from the portal venous system, which is enriched with metabolites and nutrients. Human liver has a dual blood supply, deriving 70–80% of its blood, rich in nutrients, from the portal vein and the other 20–30%, rich in oxygen, from the hepatic artery (31). Thus, Treg and T effector cells reside in the hepatic microenvironment with continuous exposure to metabolic signals (Figure 2). Resting T cells require little energy generation or expenditure; however, upon activation, their energy needs increase substantially, and they utilize glucose, amino acids, and fatty acids (FAs) to meet this demand. Metabolic effects on Treg cells could either be via direct binding of metabolites to Treg or via changes in cytokines profiles in DCs, which take up and process these metabolites.

Figure 2. Gut–liver axis and metabolites flux toward the liver. Intrahepatic T cell (including Treg cells) lineage fitness, function, survival, and proliferation are influenced by signals from the antigen presenting dendritic cells (DCs) and cytokines. The T cell receptor (TCR) binding to the foreign antigen–MHC II complex and co-stimulation provided by CD80 and CD86 binding to the T cells CD28/CTLA-4 induces T cell activation or inhibition of its function. Cytokines secreted by the DCs determine the differentiation pathway of the activated CD4 T cell to different Th1/Th2/Th17 lineages or Treg-cell survival with contact-dependent mechanism with DCs CD80/86. IL-2 is secreted in the liver by activated T effector cells, and this is required for Treg-cell survival and suppressive function. Dietary SCFAs (acetate, propionic acid, and butyrate) and MCFAs arrive to the liver via the portal vein, but LCFAs are absorbed via intestinal lymphatics and drain back into the systemic circulation via the thoracic duct. The amino acids, Glu and Arg, and glucose are also absorbed via the portal venous system towards the liver. There is always a certain degree of gut leakiness and bacterial product such as lipopolysaccharide reaches to the liver, and they rapidly undergo phagocytosis by hepatic sinusoidal Kupffer cells, which function as a sinusoidal firewall of the liver (32). The liver is enriched with fat-soluble vitamins such as vitamins A and D. DCs express immunosuppressive enzyme indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), which transform Trp into kynurenine, which is then metabolized into other catabolites through the action of enzymes within the kynurenine pathway (26, 33, 34). Trp-derived catabolites can mediate the tolerogenic effects of IDO by inducing apoptosis of activated but not resting T cells (35). Folic acid binds to folic acid receptor (FR4) on the Treg cell and Niacin (vitamin B3) interacts with GPCR109 on DCs. Glu, glutamine; Trp, tryptophan; Arg, arginine; SCFA, short-chain fatty acid; MCFA, median chain fatty acid; LCFA, long-chain fatty acid.

Glucose

Glucose is a critical fuel for Treg cell ATP generation, cell activation, and function. Glucose transporter-1 (Glut-1) levels are low in Treg cells compared with effector cells because FoxP3 limits Glut-1 expression through inhibition of Akt (36). Treg cells exhibit low to modest glycolysis compared with effector T cells along with elevated mTOR activity (37–39). Kishore and colleagues recently demonstrated that enzyme glucokinase (GCK)-dependent glycolysis regulates Treg-cell migration as GCK promotes cytoskeletal rearrangements by associating with actin. Treg cells lacking this pathway were functionally suppressive but failed to migrate to skin allografts and inhibit rejection (40).

Fatty Acids

The colonic microbiota metabolizes complex carbohydrates and undigested dietary fibers to oligosaccharides and monosaccharaides, which are then fermented to short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs); acetate, propionate, and butyrate (41). Free FAs can diffuse across the plasma membrane into the cytosol. FAs are categorized into groups based on the length of their aliphatic chain. SCFAs have 2–6 carbons; medium chain fatty acids (MCFAs) have 7–12 carbons; and long-chain fatty acids (LCFAs) have more than 12 carbons. SCFAs and MCFAs are absorbed directly into the blood via intestinal capillaries and travel through the portal vein. However, LCFAs are absorbed into the intestinal villi and reassembled again into triglycerides. The triglycerides are coated with cholesterol and protein (protein coat), forming chylomicron, which is carried via the lymphatics to drain into the systemic circulation (Figure 2). MCFAs and LCFAs are considered one of the most abundant components of the “Western diet” (42). The concentration of SCFAs is highest in the proximal colon where fermentation mostly occurs.

Short-Chain Fatty Acids

Short-chain fatty acids exert metabolic regulation by signaling through metabolite- sensing G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). GPCR43, or free fatty acid receptor 2, binds to SFCAs (43) (Figure 1). Immune cells such as Treg cells and DCs express GPR43, which bind SCFAs and promote their differentiation and function to maintain intestinal homeostasis (43). Regulation of colonic and pTreg-cell numbers also relies upon the expression of GPR103, a receptor for Niacin (vitamin B3), which is expressed on DCs, which promote Treg-cell differentiation (44, 45) (Figure 2). The SCFA, butyrate has been shown to inhibit histone deacetylase (HDAC) thereby enhancing histone acetylation in the FoxP3 promoter region to promote stable FoxP3 expression (45). Butyrate also promotes the extra-thymic induction of Treg cells via the intronic enhancer conserved non-coding sequence 1 (46).

GPCR84 recognizes MCFAs. LCFAs are transported across the membrane by fatty acid translocase (or CD36) (47) or GPCR40 (free FA receptor-1) (48) (Figure 1). The effect of LCFAs was studied recently by Haghikia and colleagues in EAE reporting that the addition of lauric acid (C12), to a culture of CD4+ T cells, not only increases the differentiation of Th1 and Th17 cells but also leads to a reduction in Treg cells (49).

Data on immunometabolism on tissue resident T cells are limited. Recent data from Pan and colleagues described that mouse CD8 tissue resident memory cells generated by viral infection of the skin differentially express high levels of molecules that mediate lipid such as fatty acid-binding proteins 4 and 5. They then continued to link this finding with human psoriatic skin suggesting the important role of FAs and their oxidative metabolism for tissue resident cells to mediate protective immunity (50).

Investigating the role of SCFAs on human T cells is in its early stage. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells of healthy donors exposed to SCFAs, especially butyrate, reduced IL-6 levels and hence increased the differentiation of Treg cells over Th17 cells (51). Indeed, this is supported by the recent data from Schmidt et al. suggesting that exposure to butyrate along with TGF-β1 enhanced Foxp3 induction in human T cells to a greater extent than TGF-β1 alone (52).

Amino Acids

Amino acids and peptides are generated in the gut via the hydrolysis of endogenous and alimentary proteins by extracellular proteases and peptidases derived from the pancreatic and other digestive enzymes and commensal bacteria residing in the gut. Amino acids can serve as sources for metabolites that enter into the metabolic tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. In the context of T cell biology, arginine (Arg), glutamine (Glu), and Trp are critical for efficient T cell function and proliferative responses.

Arg and Treg-Cell Proliferation

Metabolic activity is intimately linked to T cell function. Arg is transported to the cells by cationic transporters CAT1–4 (53) (Figure 1). BAZ1B, PSIP1, and Translin are also potential Arg sensors that promote T cell survival (54). Intracellular Arg is metabolized by arginase 1 and nitric-oxide synthase 2. The human liver contains myeloid-derived suppressor cells, which consume and deplete extracellular Arg (55). Arg-depleted environments impair T cell proliferation.

Glu and Treg Survival, Proliferation

The amino acids leucine and Glu enter into T cells via their transporter LAT1 (CD98 for leucine and ASCT2 for Glu) (Figure 1). Glu-deprived activated CD4 T cells differentiate into Treg cells rather than Th1 cells even in the presence of cytokines that would normally favor Th1 cell differentiation (56). Treg cells do not require LAT1 or ASCT2 for their differentiation in vitro (57). Treg-cell differentiation is favored during Glu deprivation (56) via mTOR signaling (58). Both leucine and Glu are positive regulators of CD4 T cell differentiation into Th1 and Th17 cells because absence of LAT1 expression impairs the differentiation of these lineages (59), and elevated Glu levels favor Th1 and Th17 cell differentiation (57). Glu-derived metabolite α-ketoglutarate promotes Th1 differentiation through enhancing mTORC1 signaling (56).

Trp and Treg-Cell Function

Dietary aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) ligands absorbed via the gut have been shown to be involved in Th17 generation (60, 61). Trp, an essential amino acid derived from ingested proteins, is one of the AhR ligands. On the other hand, IDO in DCs catabolizes Trp, resulting in localized Trp depletion. Trp-derived kyurenins are a crucial mechanism of Treg-cell suppression (62) (Figure 2). Thus, different metabolites at different stages have their own roles in T cell lineage differentiation.

Vitamins and Treg Function

Treg-cell biology depends on vitamins A, D, B3 (Niacin), and B9. Fat-soluble vitamins, vitamin A, D, E, and K, are enriched in the human liver (Figure 2). Vitamin A, RA, has an important role in Treg-cell development and function in the gut via CD103 DCs in the mesenteric lymph nodes (63). RA can also generate gut homing Treg cells (64). Vitamin B3, nicotinic acid, signals through GPCR109a and leads to expression of retinal dehydrogenases in colonic DCs, which in turn induces Treg-cell differentiation thus vitamin B3 promotes colonic Treg-cell generation (65). It is likely that these DC subsets may be present in the inflamed human liver via the portal vein (Figure 2). 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D3 inhibits T effector cell proliferation, induces Foxp3 expression, and enhances the suppressive activity of Treg cells (66). Folic acid, derived from vitamin B9, is required for DNA synthesis and repair. Human Treg cells express high level of folate receptor-4 (FR4) (67) and inhibit Treg-cell apoptosis (68) (Figure 2).

T Cell Migration and Metabolism

The majority of liver resident immune cells, including Treg cells, are normally observed within the hepatic portal tract and septum (interface hepatitis) and parenchyma (lobular hepatitis) depending on the local area of inflammatory response (69). We reported previously that the CXCR3–CXCL10 pathway is crucial for recruitment of blood Treg cells to the inflamed liver via the hepatic sinusoids (70) and the CCR6–CCL20 axis plays an essential role in the positioning of lymphocytes around the bile ducts (71). We have also shown that the survival of intrahepatic lymphocytes depends on VCAM1 expression on the bile ducts and VLA-4 expression on the lymphocytes (72). Once circulatory Treg cells are recruited via the sinusoids, their post-endothelial migration and positioning are influenced by integrin expression on the fibrous stromal framework in the liver and also the chemokines gradient (73). Some intrahepatic Treg cells may drain back to local draining portal lymph nodes, which drain the liver. In addition, the hepatic microenvironment is hypoxic, especially around the central vein region and there is a high level of lactate in the inflamed human liver. T effector cell migration is known to be highly dependent on aerobic glycolysis, and lactate seems to regulate their migration (74). Recent data suggested that glycolysis was instrumental for Treg migration and was initiated by pro-migratory stimuli via a PI3K–mTORC2-mediated pathway culminating in induction of the enzyme GCK. Subsequently, GCK promoted cytoskeletal rearrangements by associating with actin. Treg cells lacking this pathway were functionally suppressive but failed to migrate to skin allografts and inhibit rejection suggesting that GCK-dependent glycolysis regulates Treg-cell migration (40).

Epigenetic Control of T Cell Metabolism

Epigenetic mechanisms, such as histone modification, DNA methylation of CpG residues, and nucleosome repositioning, alter the accessibility of transcription factors and RNA polymerase to regulatory regions of the genome are important regulators of the immune cells and their metabolism.

Methylation

The stable expression of Foxp3, which is important for Treg cell’s suppressive function, is maintained via the demethylation of the TSDR (75, 76). However, pTreg cells show a lack of Treg-specific DNA hypomethylation, which correlates with Treg cell’s genetic signature (75). Stable Foxp3 requires DNA hypomethylation at FOXP3 CNS2 (76, 77).

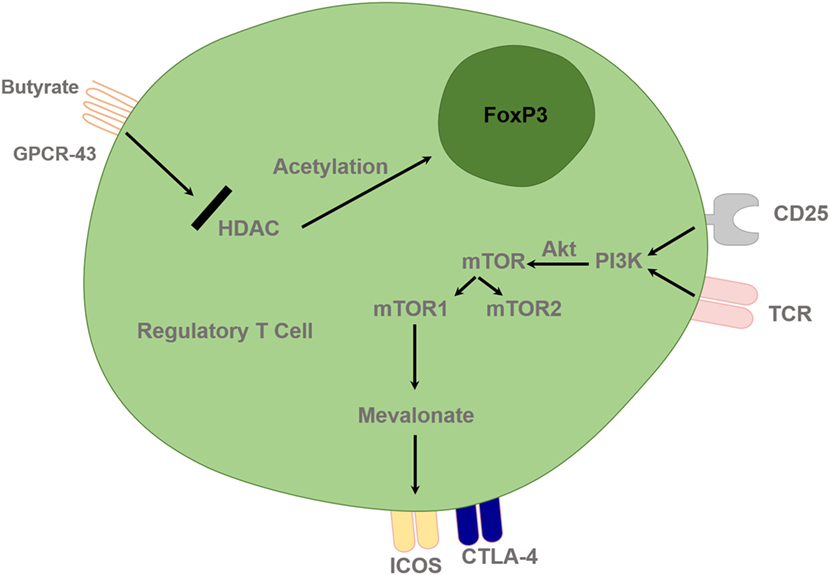

Acetylation, HDAC Inhibitor, and Metabolism

Epigenetic modifications influence the chromatin remodeling via acetylation; DNA methylation and histone modifications play a key role in the regulation of metabolic gene expression and cell differentiation, function, and recruitment. Histone acetylation by histone acetyl transferases allows gene expression and histone deacetylation by HDACs, which inhibits gene expression as well as regulating chromatin remodeling and functional transcription factors. Administration of an HDAC inhibitor (HDACi) in vivo increased Foxp3 gene expression, as well as the production and suppressive function of Treg cells. HDAC9 seems to be particularly important in regulating Foxp3-dependent suppression. HDACi therapy in vivo enhanced Treg cell-mediated suppression and decreased the degree of inflammatory bowel disease (78). Thus, pharmacological inhibitors of HDAC have potential therapeutic benefits in autoimmunity. Their action may also be mediated via immunometabolism; for example, HDAC inhibition leads to the induction Treg-cell generation by butyrate (78). HDACis, such as trichostatin A, SAHA, butyrate, and valproic acid, lead to immunomodulation by upregulating Treg-cell programming and suppressing Th1/Th17 programming (79) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Regulatory T cells are controlled by epigenetic mechanisms and T cell receptor (TCR) and interleukin-2 (IL-2) pathway. Histone acetylation facilitates FoxP3 gene expression and deacetylation inhibits gene expression. HDACi, such as butyrate, can lead to upregulation of the Treg-cell master regulatory gene, FoxP3, and enhance its function. TCR and IL-2 combined stimulation leads to PI3 kinase activation and subsequent downstream activation of mTOR signaling via Akt. Treg cells require lipogenic metabolism via the mevalonate pathway, which subsequently leads to upregulation of Treg-cell suppressive molecules cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) and ICOS in mTORC1-dependent manner. HDAC, Histone deacetylase inhibitor; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; Akt, Protein Kinase B; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; GPCR, G protein–coupled receptor.

Translational Immunometabolism of Regulatory T Cells

Manipulation of metabolism to enhance Treg-cell function in autoimmune diseases is an exciting therapeutic avenue. Dysregulated effector T cell responses and failure of T regulatory cell suppression of these effector cells is a typical feature of autoimmunity. Repurposing of current metabolic drugs and exploring new targets to change immune balance is currently an attractive translational option for clinicians and scientists who aim to apply cell metabolism for patient benefit.

Targeting Carbohydrate Metabolism

Although it is accepted that repression of Akt/mTOR, hypoxic induced factor 1-α (HIF-1α), and aerobic glycolysis is important for the efficient generation of blood Treg cells in vitro, clear evidence how these pathways impact on blood and tissue resident Treg-cell development in vivo is limited. Understanding these pathways, not only in the circulation but also at the tissue level is necessary to enhance Treg-cell metabolism and its subsequent function. Although Glut-1 expression is a critical factor in driving glycolysis in circulatory T effector cells, Treg cells’ function seems to be independently of Glut-1 (80).

HIF-1α Pathway

The hepatic environment in both inflammatory and autoimmune conditions is hypoxic as human liver receive only 25% of oxygen rich blood supply from hepatic artery, and the rest of the blood supply is from portal vein (1). Thus, targeting the transcription factor HIF-1α is a promising strategy as it exerts a crucial role in the balance between Th17 and Treg cells (81). HIF-1α predominantly affects effector T cell metabolism compared with Treg, thus there is a shift in immune cells balance under hypoxic conditions (82). HIF-1α and aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) compete for limited amounts of aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (ARNT) also know as HIF-1β. This competition is the key to the mutual regulation of HIF-1α and AhR (83) (Figure 1). ARNT serves as a common binding partner for AhR as well as HIF-1α. HIF-1α proteins are regulated in an oxygen-dependent manner, whereas ARNT is constitutively expressed, as neither ARNT mRNA nor the protein level is influenced by hypoxia. In the context of transcription factor, HIF-1α induces FoxP3, which leads to Treg-cell abundance, and Treg-intrinsic HIF-1α is required for optimal Treg function (84). HIF-1α-deficient Treg cells fail to control T-cell-mediated colitis (84).

HIF-1α is selectively expressed in Th17 cells, and its induction requires signaling through mTOR, a central regulator of glycolytic metabolism. Therefore, blocking glycolysis inhibited Th17 cell development while it promotes Treg-cell generation (39). Lack of HIF-1α in vivo has been reported to diminish Th17 cell development but enhance Treg-cell differentiation and prevent autoimmune neuroinflammation (39).

Metformin and 2-Deoxy-d-Glucose (2DG)

We reported that human liver infiltrating Treg cells are of an effector memory phenotype (16). However, intrahepatic Treg metabolic phenotype is still unexplored. When resting naive T cells are activated, they differentiate toward an effector T cell lineage due to a shift in the catabolic state of metabolism, which is driven predominantly by the glycolytic–lipogenic pathway through the TCA cycle. This upregulation of aerobic glycolysis, “Warburg effect,” is a feature of activated immune cells including T cells and is dependent on an mTOR–nutrient-sensing pathway with signaling via phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) and protein kinase B (Akt) (85). In addition, CD4 T cell differentiation into the effector T cell lineage toward Th1 or Th17 cell phenotypes is dependent on glucose and Glu for anabolic metabolism. Recent study demonstrated that CD4 effector T cells from lupus-affected mice showed elevated glycolysis and mitochondrial oxidative metabolism and inhibition of these pathways with mitochondrial metabolism inhibitor metformin and the glucose metabolism inhibitor 2DG reduced IFNγ production (86). Furthermore, blocking glycolysis via 2DG can selectively impair effector T cells thereby by improving Treg-cell function in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis (87). Antidiabetic medication, Metformin not only reduce Th17 cell responses and attenuates disease severity in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (88) but also increase numbers of Treg cells via suppressing the activation of mTOR and its downstream target, HIF-1α (89). Thus, priming the T cells with Metformin may be an attractive option to shift the immune cell balance to the regulatory arm.

Soraphen A

Th17 cells, but not Treg cells, depend on ACC1 (acetyl CoA carboxylase 1), a key enzyme that drives FA synthesis and the underlying glycolytic–lipogenic metabolic pathway for their development. Treatment with the ACC-specific inhibitor Soraphen A or T cell-specific deletion of ACC1 in mice attenuates Th17 cell-mediated autoimmune disease (90). Although Th17 cells use this pathway to produce phospholipids for cellular membranes, Treg cells readily take up exogenous FAs for this purpose. Pharmacologic inhibition or T cell-specific deletion of ACC1 not only blocks de novo FA synthesis but also interferes with the metabolic flux of glucose-derived carbon via glycolysis and the TCA cycle. Thus, the ACC1 pathway could be an attractive option to alter immune cell balance.

Phosphatase and Tensin Homolog (PTEN)

Phosphatase and tensin homolog lipid phosphatase is the main negative regulator of PI3K–Akt signaling and glycolysis in Treg cells. The activity of phosphoinositide-3-kinase (PI3K) is essential for Treg-cell lineage homeostasis and stability. Mechanistically, PTEN maintained Treg-cell stability and metabolic balance between glycolysis and mitochondrial fitness (91). Control of PI3K signaling by PTEN in Treg cells is critical for maintaining their homeostasis, function, and stability (92). PTEN deficiency upregulates activity of the metabolic checkpoint kinase complex mTORC2, and the serine–threonine kinase Akt, and loss of this activity restores functioning of PTEN-deficient Treg cells. Thus, PTEN–mTORC2 axis maintains Treg-cell stability and coordinates Treg cell-mediated control of effector responses (91), and PTEN inhibitor can lead to Treg destabilization (93).

Targeting Lipid Metabolism

Mevalonate and Statins

Cholesterol lowering medications, statins are inhibitors of the enzyme 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase, which catalyzes the formation of mevalonate, the rate-limiting step for cholesterol synthesis. As a result, statins are widely used for cardiovascular disease prevention. Statins can differentiate T cells toward Treg cells instead of Th17 cells via a mechanism dependent on protein granulation (94). In general, Treg cells require lipid and cholesterol metabolism. The mevalonate pathway is particularly important for coordinating Treg proliferation and for upregulating the suppressive molecules CTLA-4 and ICOS to establish functional competency of Treg. Mevalonate can reverse the effects of statins involved in maintaining Treg functional fitness in an mTORC1-dependent manner (37) (Figure 3). Thus, mevalonate pathway could be manipulated to enhance Treg function in autoimmunity.

However, recent work from Hu and colleagues seems to contradict this finding as they suggested that cholesterol biosynthesis and uptake programs are induced during Th17 differentiation, resulting in the accumulation of the cholesterol precursor, desmosterol, which functions as a potent endogenous RORγ agonist (95, 96). Thus, blocking cholesterol synthesis with chemical inhibitors at steps before the formation of active precursors would reduce differentiation to Th17. In addition, Simvastatin has also been shown to improve disease activity and the inflammation factor in patients with multiple sclerosis (97) and SLE (98). As there are conflicting data, more studies are required to dissect the mechanistic immunomodulatory effects of statins on Treg and Th17 cells.

Rapamycin and mTOR

The activation of mTOR, which is the catalytic subunit of the mTORC1 and mTORC2 complexes, delivers signals for the activation and differentiation of effector CD4 T cells, whereas Akt–mTOR axis is a crucial negative regulator of Treg de novo differentiation and expansion (Figure 3). mTORC1 signals through the TCR and the co-receptor CD28, and Treg cells have elevated steady-state mTORC1 activity compared with naive T cells. Signals through the TCR and IL-2 provide major inputs for mTORC1 activation, which in turn programs the suppressive function of Treg (Figure 3). Disruption of mTORC1 through Treg-specific deletion of the essential component raptor results in profound loss of Treg-cell suppressive activity and the development of a fatal early onset inflammatory disorder (37). In addition, Raptor–mTORC1 signaling in Treg cells promotes cholesterol and lipid metabolism, with the mevalonate pathway particularly important for coordinating Treg-cell proliferation and upregulation of the suppressive molecules CTLA-4 and ICOS to establish Treg functional competency (Figure 3). Thus, mTORC1 acts as a “rheostat” in Treg cells to link immunological signals from TCR and IL-2 to lipogenic pathways and functional fitness, and highlights a central role of metabolic programming of Treg suppressive activity in immune homeostasis and tolerance. All these data may lead investigators to reconsider and dissect the current use of rapamycin in good manufacturing practice (GMP) Treg-cell culture media (to prevent effector Th17 cells outgrowth) in Treg-cell therapy setting.

Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor (PPAR) Agonist—Pioglitazone

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors are nuclear receptors that regulate gene transcription. PPARα is highly expressed in liver and skeletal muscle and controls genes involved in fatty-acid oxidation (99). PPARγ is expressed in adipocytes, skeletal muscle, liver, and kidney and regulates expression of the genes that mediate metabolism (100). PPARγ agonists, thiazolidinedione drug pioglitazone, could potentially become an attractive drug candidate for anti-inflammatory therapies.

Targeting Protein Metabolism

Glu and α Ketoglutarate

Glutamine (Glu), a central anabolic nutrient in the TCA cycle, is critical for T cell survival, proliferation, and function. Glu is required for naive CD4 T cell differentiation toward Th1 and Th17 inflammatory T cells. In patients with multiple sclerosis, increased levels of both Glu and glutamate have been reported (101, 102). TCR engagement of naive CD4 T cells has been shown to trigger rapid uptake of Glu, via amino acid transporters. Glu deprivation has been shown to enhance the suppressive activity of Treg cells in an autoimmune colitis model (56). Thus, decline in Glu and α-ketoglutarate, Glu-derived TCA cycle metabolite could enhance Treg cells’ function.

Benefits and Shortcomings of Current Technology

Both glycolysis and mitochondrial respiration can be studied using a Seahorse machine for immune cell subsets including peripheral blood CD4 and CD8 T cells. Extracellular acidification rate (ECAR), a measure of lactate production by glycolysis, and mitochondrial oxygen consumption rate of both blood and tissue resident cells are necessary to analyze the metabolism and function of these cells. However, Seahorse technology is still not possible to apply for small frequency cell subset, such as regulatory T cells, to perform ECAR and OCAR experiments without cell expansion. However, expansion of the Treg will change their metabolic phenotype. Similarly, metabolic tracing with fluorescence uptake of glucose, Glu, lactate, or palmitate of Treg requires a significant number of cells. Thus, current available methodology to study tissue derived Treg is limited to Mitotracker and TMRE assays along with electron microscopy. In addition, comparing the metabolic activity of glycolysis and mitochondrial respiration in central memory (CD45RA−CCR7+), naïve (CD45RA+CCR7+), tissue resident (CD45RA+CCR7−), and effector memory (CD45RA−CCR7−) subsets of intrahepatic Treg cells is crucial to understand the metabolism and functional potential of each subset. However, investigators are limited to perform these analyses not by Seahorse technology but only by Mitotracker and TMRE assays along with electron microscopy due to the current requirement of high cell numbers. In addition, studies to assess tissue resident cell metabolism under hypoxic conditions and their migration would require a modified combined technology of hypoxic chambers or migration chambers in combination with Seahorse equipment.

Conclusion

T cell metabolism and immunology have recently been merged to form immunometabolism. Intrahepatic Treg cells can control local hepatic immune homeostasis. There is enormous potential to utilize Treg to restore tolerance in the treatment of human autoimmune diseases including autoimmune liver diseases. Modulation of immunometabolism of Treg represents a new avenue to enhance Treg-cell function and maintain a stable lineage. Immunometabolic manipulation may also have an impact on Treg cytoskeletal rearrangement and post-endothelial migration, positioning around hepatocytes and bile ducts and retention as intrahepatic tissue resident Treg. However, to date, there are no data on human liver tissue resident Treg-cell metabolism. In the future, improvement of technology may allow us to study the metabolic profile and associated function Treg. Manipulating the cell culture media to enhance the metabolism of Treg during GMP isolation and expansion and modulating the tissue and circulatory compartments with immunometabolic drugs in autoimmune patients before Treg infusion would enhance the potential of effective and successful Treg-cell therapy.

Author Contributions

RW and HB wrote the manuscript. RW and YO constructed the mechanistic Figures 1–3. YO supervised and edited the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding

This study was supported by Medical Research Council, Queen Elizabeth Hospital Charity, National Institute of Health Research Birmingham Biomedical Research Centre, and Medical Research Council Clinician Scientist Award (Grant number—G1002552).

References

1. Jeffery HC, Braitch MK, Brown S, Oo YH. Clinical potential of regulatory T cell therapy in liver diseases: an overview and current perspectives. Front Immunol (2016) 7:334. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2016.00334

2. Sakaguchi S, Sakaguchi N, Shimizu J, Yamazaki S, Sakihama T, Itoh M, et al. Immunologic tolerance maintained by CD25+ CD4+ regulatory T cells: their common role in controlling autoimmunity, tumor immunity, and transplantation tolerance. Immunol Rev (2001) 182:18–32. doi:10.1034/j.1600-065X.2001.1820102.x

3. Seddiki N, Santner-Nanan B, Martinson J, Zaunders J, Sasson S, Landay A, et al. Expression of interleukin (IL)-2 and IL-7 receptors discriminates between human regulatory and activated T cells. J Exp Med (2006) 203(7):1693–700. doi:10.1084/jem.20060468

4. Liu W, Putnam AL, Xu-Yu Z, Szot GL, Lee MR, Zhu S, et al. CD127 expression inversely correlates with FoxP3 and suppressive function of human CD4+ Treg cells. J Exp Med (2006) 203:1701–11. doi:10.1084/jem.20060772

5. Hori S, Nomura T, Sakaguchi S. Control of regulatory T cell development by the transcription factor Foxp3. Science (2003) 299:1057–61. doi:10.1126/science.1079490

6. Bennett CL, Ochs HD. IPEX is a unique X-linked syndrome characterized by immune dysfunction, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, and a variety of autoimmune phenomena. Curr Opin Pediatr (2001) 13:533–8. doi:10.1097/00008480-200112000-00007

7. Godfrey VL, Wilkinson JE, Russell LB. X-linked lymphoreticular disease in the scurfy (sf) mutant mouse. Am J Pathol (1991) 138:1379–87.

8. Zheng Y, Josefowicz S, Chaudhry A, Peng XP, Forbush K, Rudensky AY. Role of conserved non-coding DNA elements in the Foxp3 gene in regulatory T-cell fate. Nature (2010) 463:808–12. doi:10.1038/nature08750

9. Walker LS, Abbas AK. The enemy within: keeping self-reactive T cells at bay in the periphery. Nat Rev Immunol (2002) 2:11–9. doi:10.1038/nri701

10. Abbas AK, Benoist C, Bluestone JA, Campbell DJ, Ghosh S, Hori S, et al. Regulatory T cells: recommendations to simplify the nomenclature. Nat Immunol (2013) 14:307–8. doi:10.1038/ni.2554

11. Ohkura N, Kitagawa Y, Sakaguchi S. Development and maintenance of regulatory T cells. Immunity (2013) 38:414–23. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2013.03.002

12. Liu ZM, Wang KP, Ma J, Guo Zheng S. The role of all-trans retinoic acid in the biology of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Cell Mol Immunol (2015) 12:553–7. doi:10.1038/cmi.2014.133

13. O’Garra A, Barrat FJ. In vitro generation of IL-10-producing regulatory CD4+ T cells is induced by immunosuppressive drugs and inhibited by Th1- and Th2-inducing cytokines. Immunol Lett (2003) 85:135–9. doi:10.1016/S0165-2478(02)00239-0

14. Haribhai D, Williams JB, Jia S, Nickerson D, Schmitt EG, Edwards B, et al. A requisite role for induced regulatory T cells in tolerance based on expanding antigen receptor diversity. Immunity (2011) 35:109–22. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.029

15. Sakaguchi S. Regulatory T cells: key controllers of immunologic self-tolerance. Cell (2000) 101:455–8. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80856-9

16. Chen YY, Jeffery HC, Hunter S, Bhogal R, Birtwistle J, Braitch MK, et al. Human intrahepatic Tregs are functional, require IL-2 from effector cells for survival and are susceptible to Fas ligand mediated apoptosis. Hepatology (2016) 64(1):138–50. doi:10.1002/hep.28517

17. Sakaguchi S, Yamaguchi T, Nomura T, Ono M. Regulatory T cells and immune tolerance. Cell (2008) 133:775–87. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.009

18. Wing K, Onishi Y, Prieto-Martin P, Yamaguchi T, Miyara M, Fehervari Z, et al. CTLA-4 control over Foxp3+ regulatory T cell function. Science (2008) 322:271–5. doi:10.1126/science.1160062

19. Jeffery HC, Jeffery LE, Lutz P, Corrigan M, Webb GJ, Adams DH, et al. Low dose interleukin-2 promotes STAT5 phosphorylation, Treg survival and CTLA-4 dependent function in autoimmune liver diseases. Clin Exp Immunol (2017) 188(3):394–411. doi:10.1111/cei.12940

20. Deaglio S, Dwyer KM, Gao W, Friedman D, Usheva A, Erat A, et al. Adenosine generation catalyzed by CD39 and CD73 expressed on regulatory T cells mediates immune suppression. J Exp Med (2007) 204:1257–65. doi:10.1084/jem.20062512

21. Chaudhry A, Samstein RM, Treuting P, Liang Y, Pils MC, Heinrich JM, et al. Interleukin-10 signaling in regulatory T cells is required for suppression of Th17 cell-mediated inflammation. Immunity (2011) 34:566–78. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.018

22. Wu Y, Borde M, Heissmeyer V, Feuerer M, Lapan AD, Stroud JC, et al. FOXP3 controls regulatory T cell function through cooperation with NFAT. Cell (2006) 126:375–87. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.042

23. Tivol EA, Borriello F, Schweitzer AN, Lynch WP, Bluestone JA, Sharpe AH. Loss of CTLA-4 leads to massive lymphoproliferation and fatal multiorgan tissue destruction, revealing a critical negative regulatory role of CTLA-4. Immunity (1995) 3:541–7. doi:10.1016/1074-7613(95)90125-6

24. Chambers CA, Sullivan TJ, Allison JP. Lymphoproliferation in CTLA-4-deficient mice is mediated by costimulation-dependent activation of CD4+ T cells. Immunity (1997) 7:885–95. doi:10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80406-9

25. Qureshi OS, Zheng Y, Nakamura K, Attridge K, Manzotti C, Schmidt EM, et al. Trans-endocytosis of CD80 and CD86: a molecular basis for the cell-extrinsic function of CTLA-4. Science (2011) 332:600–3. doi:10.1126/science.1202947

26. Pallotta MT, Orabona C, Volpi C, Vacca C, Belladonna ML, Bianchi R, et al. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase is a signaling protein in long-term tolerance by dendritic cells. Nat Immunol (2011) 12:870–8. doi:10.1038/ni.2077

27. Borsellino G, Kleinewietfeld M, Di Mitri D, Sternjak A, Diamantini A, Giometto R, et al. Expression of ectonucleotidase CD39 by Foxp3+ Treg cells: hydrolysis of extracellular ATP and immune suppression. Blood (2007) 110:1225–32. doi:10.1182/blood-2006-12-064527

28. Lai WK, Curbishley SM, Goddard S, Alabraba E, Shaw J, Youster J, et al. Hepatitis C is associated with perturbation of intrahepatic myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cell function. J Hepatol (2007) 47:338–47. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2007.03.024

29. Goddard S, Youster J, Morgan E, Adams DH. Interleukin-10 secretion differentiates dendritic cells from human liver and skin. Am J Pathol (2004) 164:511–9. doi:10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63141-0

30. Newton R, Priyadharshini B, Turka LA. Immunometabolism of regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol (2016) 17:618–25. doi:10.1038/ni.3466

31. Oo YH, Adams DH. The role of chemokines in the recruitment of lymphocytes to the liver. J Autoimmun (2010) 34:45–54. doi:10.1016/j.jaut.2009.07.011

32. Balmer ML, Slack E, de Gottardi A, Lawson MA, Hapfelmeier S, Miele L, et al. The liver may act as a firewall mediating mutualism between the host and its gut commensal microbiota. Sci Transl Med (2014) 6:237ra66. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3008618

33. Hwu P, et al. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase production by human dendritic cells results in the inhibition of T cell proliferation. J Immunol (2000) 164:3596–9. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.164.7.3596

34. Munn DH, Sharma MD, Lee JR, Jhaver KG, Johnson TS, Keskin DB, et al. Potential regulatory function of human dendritic cells expressing indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Science (2002) 297:1867–70. doi:10.1126/science.1073514

35. Terness P, Bauer TM, Röse L, Dufter C, Watzlik A, Simon H, et al. Inhibition of allogeneic T cell proliferation by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-expressing dendritic cells: mediation of suppression by tryptophan metabolites. J Exp Med (2002) 196:447–57. doi:10.1084/jem.20020052

36. Basu S, Hubbard B, Shevach EM. Foxp3-mediated inhibition of Akt inhibits Glut1 (glucose transporter 1) expression in human T regulatory cells. J Leukoc Biol (2015) 97:279–83. doi:10.1189/jlb.2AB0514-273RR

37. Zeng H, Yang K, Cloer C, Neale G, Vogel P, Chi H. mTORC1 couples immune signals and metabolic programming to establish T(reg)-cell function. Nature (2013) 499:485–90. doi:10.1038/nature12297

38. Michalek RD, Gerriets VA, Jacobs SR, Macintyre AN, MacIver NJ, Mason EF, et al. Cutting edge: distinct glycolytic and lipid oxidative metabolic programs are essential for effector and regulatory CD4+ T cell subsets. J Immunol (2011) 186:3299–303. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1003613

39. Shi LZ, Wang R, Huang G, Vogel P, Neale G, Green DR, et al. HIF1alpha-dependent glycolytic pathway orchestrates a metabolic checkpoint for the differentiation of TH17 and Treg cells. J Exp Med (2011) 208:1367–76. doi:10.1084/jem.20110278

40. Kishore M, Cheung KCP, Fu H, Bonacina F, Wang G, Coe D, et al. Regulatory T cell migration is dependent on glucokinase-mediated glycolysis. Immunity (2017) 47:875–889.e10. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2017.10.017

41. Cummings JH, Pomare EW, Branch WJ, Naylor CP, Macfarlane GT. Short chain fatty acids in human large intestine, portal, hepatic and venous blood. Gut (1987) 28:1221–7. doi:10.1136/gut.28.10.1221

42. Montgomery MK, Osborne B, Brown SH, Small L, Mitchell TW, Cooney GJ, et al. Contrasting metabolic effects of medium- versus long-chain fatty acids in skeletal muscle. J Lipid Res (2013) 54:3322–33. doi:10.1194/jlr.M040451

43. Maslowski KM, Vieira AT, Ng A, Kranich J, Sierro F, Yu D, et al. Regulation of inflammatory responses by gut microbiota and chemoattractant receptor GPR43. Nature (2009) 461:1282–6. doi:10.1038/nature08530

44. Smith PM, Howitt MR, Panikov N, Michaud M, Gallini CA, Bohlooly-Y M, et al. The microbial metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, regulate colonic Treg cell homeostasis. Science (2013) 341:569–73. doi:10.1126/science.1241165

45. Furusawa Y, Obata Y, Fukuda S, Endo TA, Nakato G, Takahashi D, et al. Commensal microbe-derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells. Nature (2013) 504:446–50. doi:10.1038/nature12721

46. Arpaia N, Campbell C, Fan X, Dikiy S, van der Veeken J, deRoos P, et al. Metabolites produced by commensal bacteria promote peripheral regulatory T-cell generation. Nature (2013) 504:451–5. doi:10.1038/nature12726

47. Pepino MY, Kuda O, Samovski D, Abumrad NA. Structure-function of CD36 and importance of fatty acid signal transduction in fat metabolism. Annu Rev Nutr (2014) 34:281–303. doi:10.1146/annurev-nutr-071812-161220

48. Tomita T, Hosoda K, Fujikura J, Inagaki N, Nakao K. The G-protein-coupled long-chain fatty acid receptor GPR40 and glucose metabolism. Front Endocrinol (2014) 5:152. doi:10.3389/fendo.2014.00152

49. Haghikia A, Jörg S, Duscha A, Berg J, Manzel A, Waschbisch A, et al. Dietary fatty acids directly impact central nervous system autoimmunity via the small intestine. Immunity (2015) 43:817–29. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2015.09.007

50. Pan Y, Tian T, Park CO, Lofftus SY, Mei S, Liu X, et al. Survival of tissue-resident memory T cells requires exogenous lipid uptake and metabolism. Nature (2017) 543:252–6. doi:10.1038/nature21379

51. Asarat M, Apostolopoulos V, Vasiljevic T, Donkor O. Short-chain fatty acids regulate cytokines and Th17/Treg cells in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells in vitro. Immunol Invest (2016) 45:205–22. doi:10.3109/08820139.2015.1122613

52. Schmidt A, Eriksson M, Shang MM, Weyd H, Tegnér J. Comparative analysis of protocols to induce human CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells by combinations of IL-2, TGF-beta, retinoic acid, rapamycin and butyrate. PLoS One (2016) 11:e0148474. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0148474

53. Bronte V, Zanovello P. Regulation of immune responses by l-arginine metabolism. Nat Rev Immunol (2005) 5:641–54. doi:10.1038/nri1668

54. Geiger R, Rieckmann JC, Wolf T, Basso C, Feng Y, Fuhrer T, et al. l-Arginine modulates T cell metabolism and enhances survival and anti-tumor activity. Cell (2016) 167:829–842.e13. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2016.09.031

55. Resheq YJ, Li KK, Ward ST, Wilhelm A, Garg A, Curbishley SM, et al. Contact-dependent depletion of hydrogen peroxide by catalase is a novel mechanism of myeloid-derived suppressor cell induction operating in human hepatic stellate cells. J Immunol (2015) 194:2578–86. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1401046

56. Klysz D, et al. Glutamine-dependent alpha-ketoglutarate production regulates the balance between T helper 1 cell and regulatory T cell generation. Sci Signal (2015) 8:ra97. doi:10.1126/scisignal.aab2610

57. Nakaya M, Xiao Y, Zhou X, Chang JH, Chang M, Cheng X, et al. Inflammatory T cell responses rely on amino acid transporter ASCT2 facilitation of glutamine uptake and mTORC1 kinase activation. Immunity (2014) 40:692–705. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2014.04.007

58. Chapman NM, Chi H. mTOR links environmental signals to T cell fate decisions. Front Immunol (2014) 5:686. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2014.00686

59. Sinclair LV, Rolf J, Emslie E, Shi YB, Taylor PM, Cantrell DA. Control of amino-acid transport by antigen receptors coordinates the metabolic reprogramming essential for T cell differentiation. Nat Immunol (2013) 14:500–8. doi:10.1038/ni.2556

60. Veldhoen M, Hirota K, Westendorf AM, Buer J, Dumoutier L, Renauld JC, et al. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor links TH17-cell-mediated autoimmunity to environmental toxins. Nature (2008) 453:106–9. doi:10.1038/nature06881

61. Veldhoen M, Hirota K, Christensen J, O’Garra A, Stockinger B. Natural agonists for aryl hydrocarbon receptor in culture medium are essential for optimal differentiation of Th17 T cells. J ExpMed (2009) 206:43–9. doi:10.1084/jem.20081438

62. Chen W, Liang X, Peterson AJ, Munn DH, Blazar BR. The indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase pathway is essential for human plasmacytoid dendritic cell-induced adaptive T regulatory cell generation. J Immunol (2008) 181:5396–404. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.181.8.5396

63. Mucida D, Park Y, Kim G, Turovskaya O, Scott I, Kronenberg M, et al. Reciprocal TH17 and regulatory T cell differentiation mediated by retinoic acid. Science (2007) 317:256–60. doi:10.1126/science.1145697

64. Sun CM, et al. Small intestine lamina propria dendritic cells promote de novo generation of Foxp3 Treg cells via retinoic acid. J Exp Med (2007) 204(8):1775–85. doi:10.1084/jem.20070602

65. Singh N, Gurav A, Sivaprakasam S, Brady E, Padia R, Shi H, et al. Activation of Gpr109a, receptor for niacin and the commensal metabolite butyrate, suppresses colonic inflammation and carcinogenesis. Immunity (2014) 40:128–39. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2013.12.007

66. Jeffery LE, Burke F, Mura M, Zheng Y, Qureshi OS, Hewison M, et al. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3) and IL-2 combine to inhibit T cell production of inflammatory cytokines and promote development of regulatory T cells expressing CTLA-4 and FoxP3. J Immunol (2009) 183:5458–67. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0803217

67. Yamaguchi T, Hirota K, Nagahama K, Ohkawa K, Takahashi T, Nomura T, et al. Control of immune responses by antigen-specific regulatory T cells expressing the folate receptor. Immunity (2007) 27:145–59. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2007.04.017

68. Kinoshita M, Kayama H, Kusu T, Yamaguchi T, Kunisawa J, Kiyono H, et al. Dietary folic acid promotes survival of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells in the colon. J Immunol (2012) 189:2869–78. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1200420

69. Protzer U, Maini MK, Knolle PA. Living in the liver: hepatic infections. Nat Rev Immunol (2012) 12:201–13. doi:10.1038/nri3169

70. Oo YH, Weston CJ, Lalor PF, Curbishley SM, Withers DR, Reynolds GM, et al. Distinct roles for CCR4 and CXCR3 in the recruitment and positioning of regulatory T cells in the inflamed human liver. J Immunol (2010) 184:2886–98. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0901216

71. Oo YH, Banz V, Kavanagh D, Liaskou E, Withers DR, Humphreys E, et al. CXCR3-dependent recruitment and CCR6-mediated positioning of Th-17 cells in the inflamed liver. J Hepatol (2012) 57:1044–51. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2012.07.008

72. Afford SC, Humphreys EH, Reid DT, Russell CL, Banz VM, Oo Y, et al. Vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 expression by biliary epithelium promotes persistence of inflammation by inhibiting effector T-cell apoptosis. Hepatology (2014) 59:1932–43. doi:10.1002/hep.26965

73. Oo YH, Shetty S, Adams DH. The role of chemokines in the recruitment of lymphocytes to the liver. Dig Dis (2010) 28:31–44. doi:10.1159/000282062

74. Haas R, Smith J, Rocher-Ros V, Nadkarni S, Montero-Melendez T, D’Acquisto F, et al. Lactate regulates metabolic and pro-inflammatory circuits in control of T cell migration and effector functions. PLoS Biol (2015) 13:e1002202. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1002202

75. Ohkura N, Hamaguchi M, Morikawa H, Sugimura K, Tanaka A, Ito Y, et al. T cell receptor stimulation-induced epigenetic changes and Foxp3 expression are independent and complementary events required for Treg cell development. Immunity (2012) 37:785–99. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2012.09.010

76. Kim HP, Leonard WJ. CREB/ATF-dependent T cell receptor-induced FoxP3 gene expression: a role for DNA methylation. J Exp Med (2007) 204:1543–51. doi:10.1084/jem.20070109

77. Sakaguchi S, Miyara M, Costantino CM, Hafler DA. FOXP3+ regulatory T cells in the human immune system. Nat Rev Immunol (2010) 10:490–500. doi:10.1038/nri2785

78. Tao R, de Zoeten EF, Ozkaynak E, Chen C, Wang L, Porrett PM, et al. Deacetylase inhibition promotes the generation and function of regulatory T cells. Nat Med (2007) 13:1299–307. doi:10.1038/nm1652

79. Lu J, Chatain GP, Bugarini A, Wang X, Maric D, Walbridge S, et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitor SAHA is a promising treatment of cushing disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2017) 102:2825–35. doi:10.1210/jc.2017-00464

80. Macintyre AN, Gerriets VA, Nichols AG, Michalek RD, Rudolph MC, Deoliveira D, et al. The glucose transporter Glut1 is selectively essential for CD4 T cell activation and effector function. Cell Metab (2014) 20:61–72. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2014.05.004

81. Guan SY, Leng RX, Tao JH, Li XP, Ye DQ, Olsen N, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha: a promising therapeutic target for autoimmune diseases. Expert Opin Ther Targets (2017) 21:715–23. doi:10.1080/14728222.2017.1336539

82. Westendorf AM, Skibbe K, Adamczyk A, Buer J, Geffers R, Hansen W, et al. Hypoxia enhances immunosuppression by inhibiting CD4+ effector T cell function and promoting Treg activity. Cell Physiol Biochem (2017) 41:1271–84. doi:10.1159/000464429

83. Mandl M, Depping R. Hypoxia-inducible aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (ARNT) (HIF-1beta): is it a rare exception? Mol Med (2014) 20:215–20. doi:10.2119/molmed.2014.00032

84. Clambey ET, McNamee EN, Westrich JA, Glover LE, Campbell EL, Jedlicka P, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha-dependent induction of FoxP3 drives regulatory T-cell abundance and function during inflammatory hypoxia of the mucosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2012) 109:E2784–93. doi:10.1073/pnas.1202366109

85. Pearce EL, Poffenberger MC, Chang CH, Jones RG. Fueling immunity: insights into metabolism and lymphocyte function. Science (2013) 342:1242454. doi:10.1126/science.1242454

86. Yin Y, Choi SC, Xu Z, Perry DJ, Seay H, Croker BP, et al. Normalization of CD4+ T cell metabolism reverses lupus. Sci Transl Med (2015) 7:274ra218. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa0835

87. Gerriets VA, Kishton RJ, Nichols AG, Macintyre AN, Inoue M, Ilkayeva O, et al. Metabolic programming and PDHK1 control CD4+ T cell subsets and inflammation. J Clin Invest (2015) 125:194–207. doi:10.1172/JCI76012

88. Nath N, Khan M, Paintlia MK, Singh I, Hoda MN, Giri S. Metformin attenuated the autoimmune disease of the central nervous system in animal models of multiple sclerosis. J Immunol (2009) 182:8005–14. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0803563

89. Sun Y, Tian T, Gao J, Liu X, Hou H, Cao R, et al. Metformin ameliorates the development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by regulating T helper 17 and regulatory T cells in mice. J Neuroimmunol (2016) 292:58–67. doi:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2016.01.014

90. Berod L, Friedrich C, Nandan A, Freitag J, Hagemann S, Harmrolfs K, et al. De novo fatty acid synthesis controls the fate between regulatory T and T helper 17 cells. Nat Med (2014) 20:1327–33. doi:10.1038/nm.3704

91. Shrestha S, Yang K, Guy C, Vogel P, Neale G, Chi H. Treg cells require the phosphatase PTEN to restrain TH1 and TFH cell responses. Nat Immunol (2015) 16:178–87. doi:10.1038/ni.3076

92. Huynh A, DuPage M, Priyadharshini B, Sage PT, Quiros J, Borges CM, et al. Control of PI(3) kinase in Treg cells maintains homeostasis and lineage stability. Nat Immunol (2015) 16:188–96. doi:10.1038/ni.3077

93. Sharma MD, Shinde R, McGaha TL, Huang L, Holmgaard RB, Wolchok JD, et al. The PTEN pathway in Tregs is a critical driver of the suppressive tumor microenvironment. Sci Adv (2015) 1:e1500845. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1500845

94. Kagami S, Owada T, Kanari H, Saito Y, Suto A, Ikeda K, et al. Protein geranylgeranylation regulates the balance between Th17 cells and Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Int Immunol (2009) 21:679–89. doi:10.1093/intimm/dxp037

95. Hu X, Wang Y, Hao LY, Liu X, Lesch CA, Sanchez BM, et al. Sterol metabolism controls T(H)17 differentiation by generating endogenous RORgamma agonists. Nat Chem Biol (2015) 11:141–7. doi:10.1038/nchembio0915-741b

96. Santori FR. Nuclear hormone receptors put immunity on sterols. Eur J Immunol (2015) 45:2730–41. doi:10.1002/eji.201545712

97. Chataway J, Schuerer N, Alsanousi A, Chan D, MacManus D, Hunter K, et al. Effect of high-dose simvastatin on brain atrophy and disability in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (MS-STAT): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet (2014) 383:2213–21. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62242-4

98. Ulivieri C, Baldari CT. Statins: from cholesterol-lowering drugs to novel immunomodulators for the treatment of Th17-mediated autoimmune diseases. Pharmacol Res (2014) 88:41–52. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2014.03.001

99. Duval C, Fruchart JC, Staels B. PPAR alpha, fibrates, lipid metabolism and inflammation. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss (2004) 97:665–72.

100. Lefterova MI, Haakonsson AK, Lazar MA, Mandrup S. PPARgamma and the global map of adipogenesis and beyond. Trends Endocrinol Metab (2014) 25:293–302. doi:10.1016/j.tem.2014.04.001

101. Sarchielli P, Greco L, Floridi A, Floridi A, Gallai V. Excitatory amino acids and multiple sclerosis: evidence from cerebrospinal fluid. Arch Neurol (2003) 60:1082–8. doi:10.1001/archneur.60.8.1082

Keywords: regulatory T cells, microenvironment, liver, Treg plasticity, function, immunometabolism, good manufacturing practice Treg, cell therapy

Citation: Wawman RE, Bartlett H and Oo YH (2018) Regulatory T Cell Metabolism in the Hepatic Microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 8:1889. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01889

Received: 13 September 2017; Accepted: 11 December 2017;

Published: 08 January 2018

Edited by:

Claudio Mauro, Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry, United KingdomReviewed by:

Markus Feuerer, Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum (DKFZ), GermanyJohannes Herkel, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Germany

Copyright: © 2018 Wawman, Bartlett and Oo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rebecca Ellen Wawman, wawmanr@uni.coventry.ac.uk;

Ye Htun Oo, y.h.oo@bham.ac.uk

Rebecca Ellen Wawman

Rebecca Ellen Wawman Helen Bartlett

Helen Bartlett Ye Htun Oo

Ye Htun Oo