Lions, Whales, and the Web: Transforming Moment Inertia into Conservation Action

- 1Blackbeard Biologic–Science and Environmental Advisors, St. Michaels, MD, United States

- 2Animal Welfare Institute, Washington, DC, United States

- 3Wild Earth Foundation, Puerto Pirámides, Argentina

- 4University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, United Kingdom

- 5Environmental Science and Policy, George Mason University, Fairfax, VA, United States

- 6Gateway Antarctica, University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand

“I wept, because I knew that this fleeting opportunity to bridge, no matter how tenuously, the ever-widening chasm that is isolating mankind from the totality of life, had perished in a welter of human stupidity and ignorance—some part of which was mine.”

A Whale for the Killing (Mowat, 1972).

Introduction

When Farley Mowat wrote A Whale for the Killing in 1972, the titular fin whale, stranded and intentionally wounded in a Newfoundland pond, was long dead, yet the story of Moby Joe and the spectacle surrounding her death would become a cornerstone of the emerging anti-whaling movement (see below). The media frenzy that descended on the small town of Burgeo as the whale struggled to survive, and the subsequent publication of Mowat's book, are among the first examples of efforts to turn spontaneous outpourings of outrage, curiosity, or empathy into conservation action by actively focusing media attention, a phenomenon that we have dubbed moment inertia. We use “moment” because this phenomenon arises from focus of attention around a single, clarifying event, or moment, and “inertia” because that attention propagates, undirected, through media unless acted upon by outside forces, much like physical inertia. Almost half a century later, the events leading to the publication of A Whale for the Killing stand among the most effective uses of moment inertia in the conservation movement.

The unnatural deaths of individual animals can draw attention to important conservation issues such as poaching, habitat destruction, and biodiversity loss. When public interest is piqued by moment inertia, strategic campaigning can transform that interest into action. Moment inertia is fleeting and channeling public attention toward achieving wider conservation goals requires a carefully planned response to capitalize on what may, at times, seem like superficial public engagement.

Understanding moment inertia, its limitations, and how it can be used to focus and enhance existing campaigns is key for effectively realizing conservation gains. Here, we examine three cases of moment inertia—one based on outrage, one based on curiosity, and one based on empathy—and present a strategic approach for transforming this moment inertia into conservation action.

Cecil the Lion

Public outrage is often the most visible and visceral form of moment inertia. In 2015, the killing of Cecil the Lion sparked massive outcry against his hunter, trophy hunting in general, and Zimbabwean wildlife management (Nelson et al., 2016, and see Beauchamp, 2015, for a summary of the public reaction). Intense media coverage galvanized symbolic actions by remote agencies and stakeholders. While some animal welfare and wildlife conservation organizations used this event to solicit donations, in general conservation scientists and practitioners floundered. Some tried to redirect public interest toward bigger, albeit unrelated, issues, while others directed their scorn at those who were outraged, arguing that the public's attention was incorrectly focused on a marginal issue (see Howard, 2015, for an overview of the various reactions). These responses highlight a lack of understanding about the psychology of public outrage. Mass outrage responses are most often triggered by immaterially harmful acts—those with negligible long-term consequences—that permit moral signaling (Tannenbaum et al., 2011).

Examination of the timing of media events post facto shows that the initial news broke on both traditional and social media simultaneously. The initial growth phase that drove this moment inertia evolved over a 2-day period in which the story spread through multiple media markets from geographically diverse regions synchronously (Macdonald et al., 2016). This is a tell-tale sign of a concerted effort to generate “earned media,” i.e., coverage gained though newsworthiness rather than paid advertising or via owned media (Thaler, personal observation). Organizations that effectively leveraged the moment inertia surrounding Cecil the Lion took advantage of the moral signaling inherent in the public outrage model to solicit donations, grow mailing lists, and pressure philanthropists. These are tactics that can facilitate longer, less event-dependent conservation campaigns while providing instant gratification to the outraged audience.

The specific timing or location of events such as Cecil's killing cannot be predicted and mobilizing quickly to achieve positive conservation outcomes can therefore be difficult. However, while these “outrage” events appear to be random, they are often also inevitable over the long-term, and the public response can be predictable. Poaching iconic animals, negative human-animal interactions, or human-induced disasters will invariably occur and can be anticipated. Quickly pairing such events with an appropriate pre-planned response could allow conservation professionals to utilize these moments for conservation gains.

The (Non) Exploding Whale of Newfoundland

Curiosity, especially morbid curiosity, can be a powerful motivator for harnessing moment inertia. When a blue whale stranded in a small, remote port in Newfoundland, Canada in 2014 (BBC, 2014), it received some local and regional coverage while various government agencies debated who had ultimate jurisdiction over its removal (Globe and Mail, 2014). Upwell, an ocean NGO focused on analyzing ocean messaging online, identified the incident as a flashpoint to generate moment inertia (Thaler, personal observation). Upwell formed a small campaign around the event, with the following goals: draw attention to the town, which was struggling with receiving government assistance to dispose of the corpse; call attention to protections for stranded marine mammals; provide a humorous resource to inform the public about marine mammal strandings; and significantly increase the online conversation about whale strandings using Upwell's Big Listening attention model (see Weidinger et al., 2013).

Upwell initiated a social media marketing plan, mobilized a highly-engaged mailing list, and launched HasTheWhaleExplodedYet.com (now expired), which provided visitors with continuous updates about the stranding event and resources on the appropriate treatment of stranded marine mammals, as well as contact information for local and regional stranding networks.

The resulting moment inertia grew throughout a week-long news cycle, driving nearly a million unique visitors per day to HasTheWhaleExplodedYet.com. Hundreds of articles about the Newfoundland whale and whale strandings were generated, as well as about the science and broader cultural associations of exploding whales (e.g., Bhatia, 2014; Goldman, 2014; Thaler, 2014). The week-long campaign reached its zenith when an exploding whale sketch was featured on the weekly sketch comedy show Saturday Night Live (Season 39, Episode 20). The whale never actually exploded and the Royal Ontario Museum sent a team to haul the carcass away for research (O'Connor and Bailey, 2014).

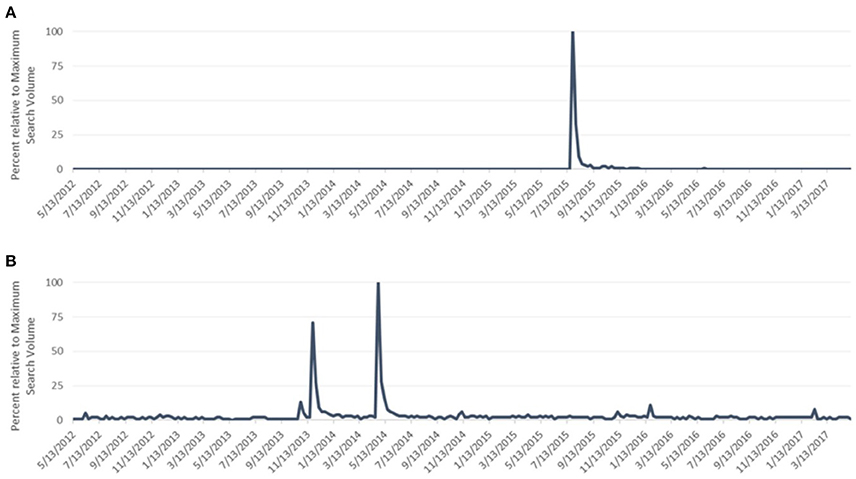

A Google trend analysis of searches for Cecil lion and exploding whale reveals the subtle differences between these two events and can help campaigners design strategies that complement these patterns. Prior to his killing, search traffic for Cecil lion was, understandably, 0% relative to maximum search volume. In the week following the killing, a significant attention spike was seen, with South Africa, Canada, the United States of America, the United Kingdom, Australia, France, and India responsible for the bulk of search volume. This spike quickly tapered to a long tail which persisted for 4 months at 1–2% of peak search volume before fading back to a 0% baseline (Figure 1A). From the period beginning 1 month after the event until May 8, 2017, the mean baseline for Cecil lion was 0.3% of the maximum, with a standard deviation of 0.67%.

Figure 1. Search volume for “Cecil lion” (A) and “exploding whale” (B) normalized against maximum search volume. Data provided by Google Trend analysis.

Prior to the Newfoundland event, search traffic for exploding whale was 1.49% relative to the maximum search volume. (Note: a smaller spike in exploding whale searches occurred in 2013 surrounding an exploding sperm whale in the Faroe Islands, which was also, in part, the result of an Upwell campaign. We have calculated the baseline from May 13, 2012 to just before the Faroe event.) Searches were more localized to Canada, the United States of America, and the United Kingdom. From the period beginning 1 month after the event until May 5, 2017, the mean baseline for exploding whale was 2.21% of the maximum, with a standard deviation of 1.25%, indicating that baseline attention almost doubled following the Newfoundland incident (Figure 1B).

The goals of a campaign will determine whether the best outcome is a large, international attention spike with a relatively short baseline shift or a smaller, more regional attention spike with a relatively longer baseline shift.

A Whale for the Killing

Farley Mowat connected the public with another whale in Newfoundland; it was 1967 and the whale was very much alive. Moby Joe was a fin whale naturally trapped in a tidal pond near the town of Burgeo. The whale was shot at by hunters and other curious onlookers. Through a wave of press releases, articles, and radio interviews, Mowat established superficial protections for the trapped whale (Mackinnon, 2014), although these ultimately proved ineffective, as the whale eventually succumbed to her injuries. When Mowat later published A Whale for the Killing, detailing the event in his unique and uncompromising style, he not only connected his audience with the whale, but also the daily struggles of the people of Burgeo. This created a narrative that had no central villain and was empathetic even to those who caused the whale harm. The book became a cornerstone document in the emerging anti-whaling movement. That Mowat was working within the technological constraints of a less connected era serves to highlight that it is not the speed, reach, and breadth of the internet and social media, but rather preparation, tactical thinking, and a little bit of luck, that transforms moment inertia into effective conservation action.

Harnessing an Inertial Moment

Though these examples vary in scope, timing, and available technologies, they can inform strategies and tactics for mobilizing moment inertia. Ephemeral events can be used to leverage donations and grow audiences, but moment inertia often falls short of producing long-term behavioral changes. A strategic, well-crafted response can encourage short-term action from legislators and other decision makers that, when combined with a larger campaign, yields lasting consequences. Building a network of experts who can speak to both the specific context of an inertial event and the broader conservation issue makes it possible to quickly tailor and deploy strategic campaigns. Nurturing a community of experts in advance has proven critical in rapidly preparing and disseminating a response to specific events (Thaler and Shiffman, 2015).

Moment inertia is, in many cases, a product of dissociation—the primary audience is generally unfamiliar with the people and places associated with the event. Any effective conservation outcome necessarily affects the people geographically and culturally tied to an issue. Campaigns that fail to understand how those most directly connected relate to these animals and ecosystems are generally ineffective (Singleton, 2016), especially when there are issues surrounding traditional or economic use tied to the community. Local allies are essential to most conservation initiatives. To establish non-exploitive, local commitment to conservation goals, effective campaigns must address the cultural values of affected communities.

Particularly in outrage-based scenarios, there is a tendency to try and identify villains to which anger can be directed, but in all situations in which there is a perceived environmental injustice, the public seeks an antagonist. In many cases the larger context precludes placing the blame on a single person or group, even where there is a clear principal actor. This can lead to substantial challenges when it comes to harnessing moment inertia: the audience is looking for immediate gratification. The villain narrative can provide a clear, achievable goal, but it can also backfire. Focusing on a discrete villain obscures larger challenges and creates an additional barrier to achieving conservation goals. Less intuitively, even in cases where blame can be placed, any attention generated from moment inertia is lost the instant “justice is served,” and may ultimately result in a decline in public concern due to the impression that the problem is solved and no further action is required.

Conservation activism following moment inertia is a balancing act between strategic planning and a quick, tactical response. When the catalyst is moral outrage, it is important to allow people to be angry, rather than to try and curb such responses. In these circumstances, it is possible to leverage predictable moral signaling into tangible conservation gains.

Regardless of the emotional reaction—outrage, curiosity, or empathy—the general guidelines for conservationists leveraging moment inertia are the same. First, planning for pseudorandom events is essential to produce meaningful outcomes. Second, understanding the limitations of campaigning on an inertial moment will help establish and achieve concrete, realistic goals. Third, the call to action must be informed by the local context, address local cultural values, and be delivered by those who can connect with the public. Finally, it is critical to maintain a factual basis while acknowledging the emotions involved.

With foresight, a focus on concrete goals, and an understanding of the strengths and limitations inherent in moment inertia, these events can be harnessed to help achieve lasting conservation successes.

Author Contributions

AT, NR, AMC, and AW participated in the Cecil the Lion panel at Fourth International Marine Conservation Congress (IMCC4) and subsequent discussions, which led to the production of this manuscript. AW drafted the initial manuscript. AT, NR, AMC, and AW contributed to revising and editing. AT performed social metric analyses.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript draws from discussions that occurred at a panel discussion at the Fourth International Marine Conservation Congress (IMCC4) and thanks are due to all those who participated. AT and AW acknowledge funding from SCB Marine Section to attend IMCC4. AT also acknowledges contributions from Patreon supporters. NR acknowledges funding from the Animal Welfare Institute to attend IMCC4 and her time to prepare this manuscript. Thanks are due to Kathleen Norman for facilitating the panel discussion and to the SCB Conservation Marketing and Engagement Working Group for funding her attendance. Funding for open-access publication were provided by the Animal Welfare Institute to NR and Patreon support to AT.

References

BBC (2014). Dead Blue Whale ‘Might Explode’ in Newfoundland Town. BBC News Service. Available online at: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-27210992 (Accessed May 10, 2017).

Beauchamp, Z. (2015). Cecil the Lion: The Killing That's Enraged the Internet, Explained. Vox. Available online at: https://www.vox.com/2015/7/28/9064325/cecil-the-lion (Accessed May 5, 2017).

Bhatia, A. (2014). What's the Pressure Inside an Exploding Whale? Wired. Available online at: https://www.wired.com/2014/05/exploding-whale-physics/ (Accessed May 10, 2017).

Globe Mail (2014). Newfoundlanders Fear Whale Carcass Will Explode as Town Seeks Help Removing It. The Globe and Mail. Available online at: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/carcass-of-blue-whale-rotting-along-newfoundland-shoreline-could-explode/article18335639/ (Accessed July 17, 2017).

Goldman, J. G. (2014). Did Exploding Whales Just Go Mainstream? Gizmodo. Available online at: http://gizmodo.com/did-exploding-whales-just-go-mainstream-1574979169 (Accessed May 10, 2017).

Howard, B. C. (2015). Killing of Cecil the Lion Sparks Debate Over Trophy Hunts. National Geographic. Available online at: http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2015/07/150728-cecil-lion-killing-trophy-hunting-conservation-animals/ (Accessed July 17, 2017).

Macdonald, D. W., Jacobsen, K. S., Burnham, D., Johnson, P. J., and Loveridge, A. J. (2016). Cecil: a moment or a movement? analysis of media coverage of the death of a lion, Panthera leo. Animals 6:26. doi: 10.3390/ani6050026

Mackinnon, J. B. (2014). Farley Mowat, 1921–2014. Orion Magazine. Available online at: https://orionmagazine.org/2014/05/farley-mowat-1921-2014/ (Accessed May 10, 2017).

Nelson, M. P., Bruskotter, J. T., Vucetich, J. A., and Chapron, G. (2016). Emotions and the ethics of consequence in conservation decisions: lessons from Cecil the lion. Conserv. Lett. 9, 302–306. doi: 10.1111/conl.12232

O'Connor, J., and Bailey, S. (2014). Newfoundland's Dead (but Still Unexploded) Blue Whale Headed To Toronto's ROM. National Post. Available online at: http://news.nationalpost.com/news/canada/newfoundlands-dead-but-still-unexploded-blue-whale-headed-to-torontos-rom (Accessed May 5, 2017).

Singleton, B. E. (2016). Love-iathan, the meat-whale and hidden people: ordering Faroese pilot whaling. J. Polit. Ecol. 23, 26–48. Available online at: http://oru.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A911586&dswid=-6780

Tannenbaum, D., Uhlmann, E. L., and Diermeier, D. (2011). Moral signals, public outrage, and immaterial harms. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 47, 1249–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2011.05.010

Thaler, A. (2014). The History of Exploding Whales Is the History of the Internet Itself. Motherboard. Available online at: https://motherboard.vice.com/en_us/article/the-history-of-exploding-whales-is-the-history-of-the-internet-itself (Accessed May 5, 2010).

Thaler, A., and Shiffman, D. (2015). Fish tales: combating fake science in popular media. Ocean Coast. Manag. 115, 88–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2015.04.005

Weidinger, R., Dearborn, R., Fitzgerald, M., Dugas, A., Mulvaney, K., and Bravo, B. (2013). Upwell Pilot Report. Available online at: https://www.scribd.com/document/132870440/Upwell-Pilot-Report-2013 (Accessed May 10, 2017).

Keywords: social media, cecil the lion, farley mowat, moment inertia, trophy hunting

Citation: Thaler AD, Rose NA, Cosentino AM and Wright AJ (2017) Lions, Whales, and the Web: Transforming Moment Inertia into Conservation Action. Front. Mar. Sci. 4:292. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2017.00292

Received: 02 June 2017; Accepted: 28 August 2017;

Published: 14 September 2017.

Edited by:

Edward Jeremy Hind-Ozan, Cardiff University, United KingdomReviewed by:

Daniella Rabaiotti, Zoological Society of London, United KingdomSamantha Andrews, Memorial University of Newfoundland, Canada

Copyright © 2017 Thaler, Rose, Cosentino and Wright. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Andrew D. Thaler, andrew@blackbeardbiologic.com

Andrew D. Thaler

Andrew D. Thaler Naomi A. Rose

Naomi A. Rose A. Mel Cosentino

A. Mel Cosentino Andrew J. Wright

Andrew J. Wright