- 1Hubei Key Laboratory of Ecological Restoration for River-Lakes and Algal Utilization, College of Resources and Environmental Engineering, Hubei University of Technology, Wuhan, China

- 2College of Life Science, Central China Normal University, Wuhan, China

- 3Department of Aquatic Ecology, Netherlands Institute of Ecology, Wageningen, Netherlands

Elevated pCO2 and warming are generally expected to influence cyanobacterial growth, and may promote the formation of blooms. Yet, both climate change factors may also influence cyanobacterial mortality by favoring pathogens, such as viruses, which will depend on the ability of the host to adapt. To test this hypothesis, we grew Plectonema boryanum IU597 under two temperature (25 and 29°C) and two pCO2 (400 and 800 μatm) conditions for 1 year, after which all treatments were re-exposed to control conditions for a period of 3 weeks. At several time points during the 1 year period, and upon re-exposure, we measured various infection characteristics of it associated cyanophage PP, including the burst size, latent period, lytic cycle and the efficiency of plaquing (EOP). As expected, elevated pCO2 promoted growth of P. boryanum equally over the 1 year period, but warming did not. Burst size increased in the warm treatment, but decreased in both the elevated pCO2 and combined treatment. The latent period and lytic cycle both became shorter in the elevated pCO2 and higher temperature treatment, and were further reduced by the combined effect of both factors. Efficiency of plaquing (EOP) decreased in the elevated pCO2 treatment, increased in the warm treatment, and increased even stronger in the combined treatment. These findings indicate that elevated pCO2 enhanced the effect of warming, thereby further promoting the virus infection rate. The re-exposure experiments demonstrate adaptation of the host leading to higher biomass build-up with elevated pCO2 over the experimental period, and lower performance upon re-exposure to control conditions. Similarly, virus burst size and EOP increased when given warm adapted host, but were lower as compared to the control when the host was re-exposed to control conditions. Our results demonstrate that adaptation but particularly physiological acclimation to climate change conditions favored viral infections, while limited host plasticity and slow adaptation after re-exposure to control conditions impeded host biomass build-up and viral infections.

Introduction

The climate is changing at an unprecedented rate, and atmospheric pCO2 is predicted to have doubled from 400 μatm today to 800 μatm by the end of this century. Elevated pCO2, together with increases in concentrations of other greenhouse gases, is predicted to enhance the average global temperature by up to 4.8°C (Stocker et al., 2013). Phytoplankton play a key role in global carbon cycling, and contribute to approximately 50% of the CO2 fixed by the entire biosphere (Field et al., 1998). Photosynthesis and carbon fixation are expected to increase further with elevated pCO2 in both marine (Hein and Sand-Jensen, 1997) as well as freshwater ecosystems (Verspagen et al., 2014a). Elevated pCO2 may particularly favor photosynthesis and growth of cyanobacteria, as they feature among the lowest affinity enzymes for carbon fixation, i.e., ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RubisCO) type 1D (Badger et al., 2006; Raven et al., 2008). Cyanobacterial blooms are furthermore associated to warm conditions, and it is thus this phytoplankton group that may be particularly favored by climate change (Paerl and Huisman, 2009; Carey et al., 2012; Kosten et al., 2012; O'Neil et al., 2012). The responses of cyanobacteria to climate change will also depend on their adaptive abilities (Walworth et al., 2016). Earlier studies, however, did not find evidence for evolutionary change toward elevated pCO2 in two freshwater cyanobacteria species (Low-Décarie et al., 2013), while data on warming effects seems currently lacking.

The success of phytoplankton species in future waters will not only depend on their growth and abilities to adapt, but also on mortality factors, notably their pathogens, such as viruses (Suttle, 2007). Viruses control the structure of entire phytoplankton communities as they play a key role in regulating host population densities, the cycling of carbon and nutrients (Fuhrman, 1999; Weinbauer, 2004; Jover et al., 2014), as well as in host evolution via horizontal gene transfer (Thompson et al., 2011) and genotype selection (Suttle, 2007). Cyanophages (i.e., cyanobacteria viruses) have been reported for a wide range of species, including notorious toxin producers, such as Nodularia, Dolichospermum (formerly Anabaena; Wacklin et al., 2009), Planktothrix, Aphanizomenon and Microcystis (Jenkins and Hayes, 2006; Yoshida et al., 2006; Gao et al., 2012; Ou et al., 2015; Sulcius et al., 2015), and were reported to remove up to 97% of the potential filamentous cyanobacterial production in a shallow eutrophic lake (Tijdens et al., 2008).

Climate change may alter virus-host interactions, and will thereby affect the functioning of aquatic food-webs (Danovaro et al., 2011). Elevated pCO2 and warming were reported to have a range of effects on the viral infection of phytoplankton. For instance, elevated pCO2 may enhance (Zhou et al., 2015) or inhibit (Larsen et al., 2008) viral infections, while some studies also reported a lack of effect (Maat et al., 2014). With respect to infection characteristics, burst size was shown to increase (Carreira et al., 2013; Zhou et al., 2015) or decrease (Traving et al., 2014) with elevated pCO2, and also the latent period did not show unambiguous results even within a single virus-host system (Traving et al., 2014). Comparably, warming was shown to cause an increase in infections, as indicated by enhanced virus concentrations (Honjo et al., 2007; Chu et al., 2011; Mankiewicz-Boczek et al., 2016), but may also reduce infections, depending on the specific virus (Tomaru et al., 2014), as well as on temperature dependent host resistance (Kendrick et al., 2014).

The effects of elevated pCO2 and warming on virus-host interactions have thus been investigated in various host species from distinct ecosystems, yet results remain ambiguous and only little is known about their combined effects over different temporal scales. Elevated pCO2 combined with warming were shown to affect key phytoplankton traits, such as enhanced growth rates with reduced cell sizes (Fiorini et al., 2011), increased carbon:nutrient ratios (Fu et al., 2007, 2008; Muller et al., 2014; Verspagen et al., 2014b; Paul et al., 2015), and enhanced primary production (Holding et al., 2015). Viruses rely on their host cells for reproduction, and the success of an infection thus strongly depends on the physiological status of a host (Mojica and Brussaard, 2014). In other words, conditions enhancing growth of a host, may also promote growth of their virus. Consequently, we predict that elevated pCO2 and warming will facilitate viral infections of a cyanobacterial host, and that their combined effect will be synergistic. Moreover, with a generation time of about 2 days we expect that host cells will adapt over a 1 year period under the imposed conditions, as this covers over 150 generations, which will further enhance viral infections. To test these hypotheses, we exposed the freshwater cyanobacterium Plectonema boryanum to elevated pCO2, warming and a combination of both, and followed key physiological traits of the host and its cyanophage over 1 year period, as well as after re-exposure to control conditions. More specifically, traits of the host included growth rate, cell size and chlorophyll-a contents, which are key parameters indicating host fitness. For the cyanophage, we assessed the latent period (the period from host infection to initial phage release), the lytic cycle (the period from host infection to complete phage release), and burst size (the average number of phages released from a single infected host cell). Moreover, we tested the efficiency of plaquing (EOP), which is proportion of cyanophages that can successfully infect to host in 1 h.

Materials and Methods

Cyanophage and Cyanobacteria

Cyanophage PP is a podovirus with a linear, double-stranded DNA genome that has been frequently detected at high levels in many eutrophic lakes in China (Cheng et al., 2007). The experiments were performed with a cyanophage PP lysate containing >108 plaque forming units (PFU) mL−1 that was stored at 4°C. The cyanobacterium P. boryanum IU597, obtained from the FACHB-collection, Wuhan City, China, was cultivated in AA medium (Allen and Arnon, 1955), with 30 μmol photons m−2 s−1 white light (Philips, Lifemax TLD 36W/865, China) and a 12:12 h light:dark cycle. Experiments were performed in 200 mL growth medium in triplicate, and incubated in self-made chambers at different combinations of pCO2 and temperatures: 400 μatm pCO2 and 25°C (control), 400 μatm pCO2, and 29°C (warm treatment), 800 μatm pCO2 and 25°C (elevated pCO2 treatment), and 800 μatm pCO2 and 29°C (combined treatment). Additional CO2 for the elevated pCO2 treatment was supplied to the headspace, and was measured using a Telaire 7001 CO2 sensor (USA). Initial pH reflected the CO2 treatments with values of 6.72, 6.71, 6.50, and 6.52, for the control, warm, elevated pCO2 and combined treatment, respectively.

To prevent transient effects of elevated pCO2 and warming on host growth, P. boryarum was conditioned to the above treatments for 1 year during which the cultures were re-inoculated by diluting the cell density to 2.0 × 106 cells mL−1 with AA medium every 15 days. Then, the cultures in each condition were all re-exposed to the control condition for a period of 3 weeks (i.e., a common garden experiment). Host growth and viral infectivity were tested at 6, 9, and 1 year within 1 year and also after the re-exposure to control conditions. Cells were counted and cell size was measured by microscopy (E600, Nikon, Japan) using a hemocytometer, and the chlorophyll-a (chl-a) concentration was measured by acetone extraction (Chen et al., 2005) at day 7. The growth rate of the host (μ) was calculated assuming exponential growth based on cell numbers at the start of the experiment and at day 7 according to:

Where X7 and X0 represent P. boryarum cell densities at day 7 (i.e., t7) and day 0 (i.e., t0), respectively. All experiments started with the same initial cell densities (i.e., t0) of 2.0 × 107 cells mL−1 by dilution with AA medium.

P. boryarum cultures were subsequently used to assess key viral traits, including latent period, lytic cycle, and the average burst size with one-step growth assays, and EOP with plaque assays.

One-Step Growth Assay

The one-step growth assays were performed to assess the latent period, lytic cycle, and the average burst size. The effect of initial multiplicity of infection (MOI, i.e., the number of phages per host cell) on the latent period and burst size is specific for any particular virus-host system (Sulcius et al., 2015). The MOI is typically set at about 1 phage per host cell for uni- or bicellular hosts to avoid host cell infection by more than one phage, and also to ensure that most of the cells will be infected in only one step (Bratbak et al., 1998; Yoshida et al., 2006). However, P. boryanum used in our study grows in trichomes, consisting of up to 800 cells. Assuming a viral adsorption fraction of 10% (i.e., fraction of viruses that adsorp to a host) and a burst size of 100 PFU cell−1, an initial MOI of more than 0.125 × 10−3 would lead to multiple infections after a first round of lysis. Thus, in this one-step growth assay, host cell suspensions (50 mL) were mixed with a cyanophage lysate at a sufficiently low MOI of 0.1 × 10−4. After 30 min of steady incubation to allow adsorption, the mixtures were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min at the corresponding culture temperature. The pellets were collected, washed twice in AA medium, and then resuspended in 50 mL of AA medium and incubated in the chambers described above. For the plaque assays (Suttle, 1993), 0.1 and 1 mL samples from these resuspended cultures were plated at 0, 60, 90, 120, 180, 240, 300, 360, and 390 min. After constructing one-step growth curves (Supplementary Figure 1) with cyanophage titres at each time point relative to those at t0, the latent period, lytic cycle and average burst size were determined using a modified Gompertz sigmoid growth function (Zwietering et al., 1990) including the addition of a normalized initial PFU of 1:

where y indicates the titre at time t, B the burst size (i.e., the maximum relative PFU), rm the maximum infection rate, e the mathematical constant (i.e., 2.718), and λ is the latent period indicated by the point on the x-axis where the slope from the maximum increase crosses y = 1. Fits were performed using least square fitting with the Microsoft Excel 2013 Solver GRG nonlinear fitting procedure with multistart of population size of 200. The lytic cycle was estimated based on the relative PFU data as the time when the burst size B was reached.

EOP Assay

For the EOP assay, host cell suspensions were sampled and a cyanophage lysate was added with a MOI of 0.1 × 10−3. The titer of the mixture was recorded as P0. Such a low MOI should prevent multiple phages attaching to a single trichome, which consisted of 120 cells on average with exceptions of up to 800 cells. These mixtures were subsequently incubated for 1 h for viral adsorption, without shaking, in the chambers described above. To assess the number of infected hosts at the end of the assay (P1), 1.5 mL of sample was centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min at the corresponding culture temperature. The supernatant containing free cyanophages was removed, and the titres of the pellets containing infected cyanobacteria were subsequently determined by plaque assay (Suttle, 1993). The EOP over a 1 h period was calculated as P1/P0.

Statistical Analysis

Data was log transformed before statistical analysis to improve equality of variances. Normality and equality of variances were confirmed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and Levene's test, respectively. Significant differences between treatments were tested using a one-way ANOVA, and followed by post-hoc comparison of the means using S-N-K test if normality was confirmed, otherwise the Games-Howell test was applied. Statistics were performing with SPSS Statistics 17.0 (IBM Inc., USA), the figures were made by GraphPad Prism 5.01 (GraphPad Inc., USA), and all values represent means (n = 3) ± standard deviation (SD). Significant differences between treatments were indicated by different lowercase letters.

Results

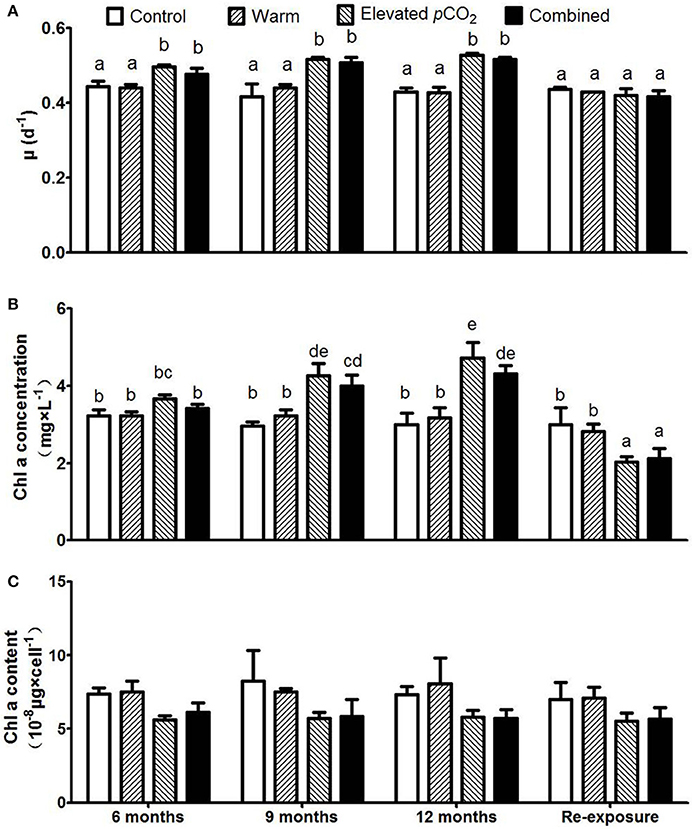

The growth rates of P. boryanum were significantly higher in the elevated pCO2 and combined effect treatments as compared to the control conditions (Figure 1A, P < 0.05), and were in accordance with the observed effects on Chl-a concentrations (Figure 1B). While growth rate remained unaltered during the course of 1 year in these two treatments, host cell density (Supplementary Figure 2) and Chl-a concentrations showed a gradual increase (P < 0.05). Cellular Chl-a contents did not significantly change with warming, elevated pCO2, nor their combined effect, though tended to be higher in the warm treatment compared to the elevated pCO2 and combined effect treatment (Figure 1C). After re-exposure to control conditions, Chl-a concentrations in the elevated pCO2 and combined treatment turned to lower than the control (P < 0.05).

Figure 1. Responses of Plectonema boryanum to elevated pCO2, temperature and a combination of both treatments with growth rate (A), Chl-a concentration (B), and Chl-a content per cell (C). Bars show mean ± SD (n = 3). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between treatments (one-way ANOVA, P < 0.05).

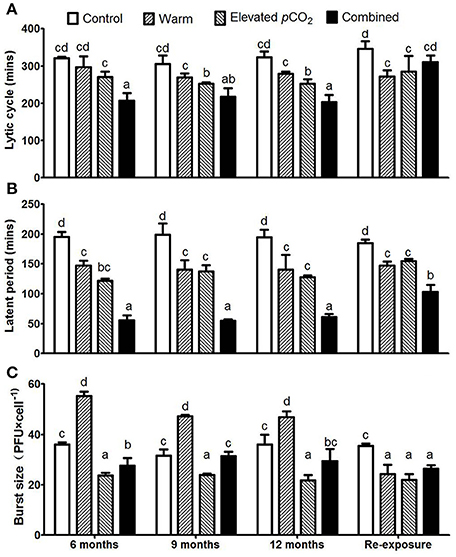

The lytic cycle, latent period and burst size remained largely unaltered over the course of the 1 year period (Figure 2). However, the lytic cycle was reduced from 316 ± 10 min in the control to 282 ± 14 min and 256 ± 11 min for warming and elevated pCO2 treatment, respectively (Figure 2A, P < 0.05). When both factors were combined, the lytic cycle further shortened down to 209 ± 8 min. The lytic cycle includes the latent period, which was strongly reduced from 196 ± 3 min in the control, down to 143 ± 4, 129 ± 8, and 57 ± 3 min in the warming, elevated pCO2 and combined effect treatment, respectively (Figure 2B; P < 0.05). The difference between the lytic cycle and latent period (Δt) did not differ between the treatments (Supplementary Figure 3), thus indicating that the shorter lytic cycles were a result of a shorter latent period. Upon re-exposure to control conditions, the lytic cycle and latent period remained lower for warming and elevated pCO2 treatments as compared to the control (Figures 2A,B; P < 0.05), while the lytic cycle and latent period turned to increase in the combined treatment as compared to before re-exposure (Figures 2A,B; P < 0.05).

Figure 2. The dynamic parameters of one step growth curves for each treatment with lytic cycle (A), latent period (B), and average burst size (C). Bars show mean ± SD (n = 3). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between treatments (one-way ANOVA, P < 0.05).

Burst size increased from 35 ± 3 PFU cell−1 to 50 ± 5 PFU cell−1 in response to warming (P < 0.05), whereas it decreased to 23 ± 1 PFU cell−1 with elevated pCO2 (Figure 2C; P < 0.05). Both factors seemed to counteract each other when combined, as the burst size of the combined effect treatment was 29 ± 2 PFU cell−1 and thus demonstrated no significant difference to the control. The combined effect of elevated pCO2 and warming on burst size and latent period seems additive rather than interactive. After re-exposure to the control conditions, the burst size was lower as compared to the control for all climate change factors (Figure 2C; P < 0.05).

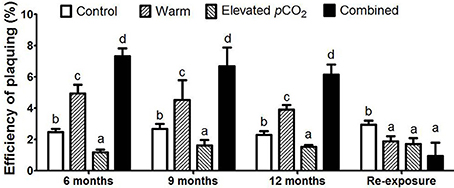

The EOP was not influenced by the duration of exposure, but increased from 2.5 ± 0.2% in the control to 4.5 ± 0.5% in the warm treatment, whereas it decreased down to 1.5 ± 0.2% in the elevated pCO2 treatment (Figure 3). Together, warming and elevated pCO2 resulted in an EOP of 6.7 ± 0.6%, indicating a clear interactive effect of elevated pCO2 and warming on EOP (P < 0.05). In other words, the increase in EOP with warming was further enhanced with elevated pCO2, and both factors thus synergistically favored infection by cyanophage PP. After re-exposure to control conditions, EOP responded similarly as the burst size, with a significant decrease as compared to the control in all climate change treatments (Figure 3; P < 0.05).

Figure 3. The EOP for each treatment. Bars show mean ± SD (n = 3). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between treatments (one-way ANOVA, P < 0.05).

Discussion

Physiological Acclimation and Evolutionary Adaptation of Host and Virus

The growth rates of P. boryanum ranged from 0.42 to 0.53 in this work, and it was lower than P. boryarum UTEX 485 (Miśkiewicz et al., 2000), but higher than P. boryarum AUCC 143 (Prasad et al., 2005). Cyanobacteria possess RubisCO 1D with a low affinity for CO2 (Badger et al., 2006), and their growth was thus expected to be favored with elevated pCO2. Indeed, growth and biomass build-up (as indicated by Chl-a concentration) of P. boryanum showed a consistent increase with elevated pCO2 and with elevated pCO2 combined with warming over the 1 year period. Yet, after a 3 week period of re-exposure to control conditions, growth was similar to the control conditions while biomass build-up was lower for cells grown at both conditions. The observed gradual increase in biomass build-up over the 1 year period may indicate adaptation to elevated pCO2 levels. Moreover, these results suggest that this adaptive response regarding biomass build-up becomes unfavorable when exposed again to low CO2 availabilities. These findings are in contrast to earlier studies that did not reveal evolutionary adaptation in cyanobacteria (Low-Décarie et al., 2013), but seems comparable to observations on the green alga Chlamydomonas, showing reduced growth rates upon a short re-exposure to ambient pCO2 conditions after long-term elevated pCO2 exposure (Collins and Bell, 2004).

Adaptation to elevated pCO2 thus seem favorable for Plectonema as it could reach higher biomass build-up, but this will only occur if CO2 levels will remain high for a sufficient number of generations. In our experiment, Plectonema was exposed to the climate change factors for over 150 generations, which appeared sufficiently long to allow adaptive responses. CO2 concentrations in productive freshwater systems may vary substantially at short time scales as result of uptake of CO2 via photosynthesis (Verspagen et al., 2014a). Under such conditions, adaptation is likely not occurring and the success of a species will largely depend on the physiological acclimation (i.e., phenotypic plasticity). In less productive waters, CO2 concentrations may become high and remain more stable. Under such conditions, adaptive responses are more likely to occur. In contrast to our expectations, warming did not cause an increase in growth or biomass build-up in our study. This is surprising, as cyanobacteria tend to have higher growth optima with a generally broad temperature range (Lürling et al., 2013). An earlier study with P. boryanum did show an increase in growth rate and biomass build-up after 16 h of warming from 15 to 29°C (Miśkiewicz et al., 2000). Our control conditions were performed at 25°C, which may have already been the growth optimum for this species. Although a warming of 4°C is likely to affect P. boryanum metabolism, it did not result in differences in growth rate or biomass build-up. Moreover, it seems that warming did not alter the response of the host to elevated pCO2. Impacts of warming will thus not only depend on the extent by which temperature increases, but also on the temperature range where these changes occur relative to an organism's growth optimum.

Although virus infection dynamics changed with climate change factors, the observed responses remained largely unaltered over the 1 year period (i.e., the response after 1 year was similar to the response after 6 months). This suggests that virus infection dynamics were insensitive to the changes in host fitness, or that the changes in host fitness over the course of 1 year were too small relative to the differences between the treatments. Consequently, the main response of virus infections follows host physiological acclimation rather than adaptation. Interestingly, burst size and infection efficiency (i.e., EOP) of the virus showed a completely reversed response when provided with host cells that were re-exposud to control conditions after having grown in the warm and/or combined treatment. This may indicate that host cells were adapted to the warm and combined conditions, and that upon re-exposure the physiological acclimation to control conditions reduced the virus burst size and infection efficiency. Thus, host adaptation but particularly physiological acclimation to climate change factors are responsible for the observed shifts in viral infectivity.

Infection Dynamics

Our result show various CO2 and temperature effects on cyanophage infection characteristics, and both factors may promote but also impede infections. For instance, elevated pCO2 led to a shorter latent period but also a reduced burst size. Thus, faster infection cycles are accompanied by a reduced production of offspring phages. Such a trade-off has also been reported earlier for a cyanophage-Synechococcus system where a shorter latent period in response to a lower pH was accompanied by a reduced burst size (Traving et al., 2014). Under elevated pCO2, growth rate of the host increased which may have led to a shorter latent period and consequently result in a smaller burst size, as there is less time for phage production (Gnezda-Meijer et al., 2006). Impacts of elevated pCO2 on the burst size of phytoplankton viruses, however, do not seem unambiguous. For instance, burst size of an Emiliania huxleyi virus was shown to increase (Larsen et al., 2008) or decrease (Carreira et al., 2013), while no pCO2 dependent change in burst size was observed for a Micromonas pusilla virus (Maat et al., 2014), though in the latter the host was P-limited. Warming alone caused a shorter latent period along with higher burst size, which was also reported for the Lactococcal phage P008 (Mueller-Merbach et al., 2007) and the Streptococcus phage phi18 (Sanders and Klaenhammer, 1984). This suggests that warming may favor phage development, possibly by stimulating enzymes involved in phage production (Chu et al., 2011), and/or inhibit cellular defense mechanisms against phage infection (see also below) (Sanders and Klaenhammer, 1984; Durmaz and Klaenhammer, 2007). The combined effect of warming and elevated pCO2 on latent period and burst size were additive, resulting in a further shortening of the latent period but a reduced overall effect on burst size.

Infection Efficiency

Phage infection generally depends on (1) the contact rate between the phage and host, and (2) phage resistance mechanisms by the host cell. The rate of contact is influenced by the concentration of host and virus, host cell size, temperature, and viscosity of the water (Murray and Jackson, 1992). Indeed, virus infections seem generally density dependent (Murray and Jackson, 1992), and larger host cells were shown to provide a greater surface area for contact (Hadas et al., 1997). In the EOP assay, host, cyanophage concentration and the cell size were similar between treatments (Supplementary Figure 4), and these factors thus cannot explain differences in EOP. In the warm treatments, water temperature was increased from 25 to 29°C, with a consequent decrease in water viscosity from 0.8937 mPa × s to 0.8180 mPa × s. This would lead to an increased contact rate by 10.7% (Murray and Jackson, 1992). Thus, the observed increase in EOP in the warm and combined effect treatments could, at least partially, be explained by a temperature dependent decrease in water viscosity.

Efficiency of plaquing (EOP) was more than 50% higher in the warm treatment compared to the control, which is comparable to earlier reports on plaquing efficiency with a cyanophage—Dolichospermum system (Currier and Wolk, 1979). This suggests that warming may impede phage resistance mechanisms by the host cell, including (1) blocking of adsorption, (2) blocking of phage DNA injection, (3) DNA restriction/modification (R/M), and (4) abortive infection (Abi), which may be the main reason for the higher EOP. Both higher pH (caused by lower pCO2) and higher temperature (Benedi et al., 1991) can lead to a higher lipopolysaccharide content on the cell surface that may act as receptor for cyanophage adsorption (Samimi and Drews, 1978). Thus, elevated pCO2, resulting in lower pH, may reduce adsorption, while warming may enhance adsorption via changes in the cell surface lipopolysaccharides. Also DNA injection was shown to be influenced by both pH and temperature (Kumar Sarkar et al., 2006), and an increase in temperature was furthermore shown to enhance DNA injection (Labedan and Goldberg, 1979). Higher temperatures may also promote the DNA ejection rate, which could be explained by a temperature induced conformational change in the tail pore-forming proteins allowing phage DNA to pass through faster (Lof et al., 2007). R/M systems are widely distributed in bacteria as well as in unicellular and filamentous cyanobacteria (Szekeres et al., 1983; Zhao et al., 2006; Stucken et al., 2013). The activity of R/M systems mainly depends on various restriction endonucleases to digest phage DNA, with distinct optimal digestion temperatures and pH (Sanders and Klaenhammer, 1984; Guimont et al., 1993; Dempsey et al., 2005). Lastly, Abi systems can cause a disruption of phage development after early phage gene expression, resulting in a decrease in death of the infected cells and/or a reduction in phage burst size (Emond et al., 1997; Tangney and Fitzgerald, 2002). The activity of Abi genes may be up- or down-regulated by temperature (Tangney and Fitzgerald, 2002; Bidnenko et al., 2009), but there is no report on the influence of pCO2 or pH on Abi gene activity.

Elevated pCO2 magnified the positive effect of warming on EOP, even though elevated pCO2 alone caused a decrease in EOP. These surprising interactive effects suggest a dependency of infection characteristics on both temperature and pCO2. Dissociation of the cell puncturing complex of phages is essential for phage DNA injection, and was shown to be controlled by both pH and temperature (Kumar Sarkar et al., 2006). Specifically, a decreasing pH slowed down the dissociation of a protein complex that is involved in host resistance (i.e., (gp5*)3(gp5C)3) when temperature was 0°C, while the dissociation of the same complex was accelerated by a decreasing pH at 20°C. These results suggest that the optimal pH for phage DNA injection could vary strongly with temperature. Warming and elevated pCO2, together with associated changes in pH, may thus affect the resistance of a host to phage infection. Future studies should further elucidate the complex interplay between climate change effects on phage associated traits and host defense mechanisms.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the mechanisms responsible for the combined effects of elevated pCO2 and elevated temperature on the infectivity of cyanophage are complex and poorly understood. Although we observed host adaptation to the climate change factors, the strongest virus responses seem a result of host physiological acclimation. Warming was shown to increase EOP, as well as reduce the latent period and increase burst size, while elevated pCO2 reduced EOP, latent period and burst size. Thus, warming seems to generally promote phage infections, while elevated pCO2 differentially affects various components of phage infections. The observed effects of both climate change factors are additive, except for EOP for which the increase with warming was promoted by elevated pCO2. Thus, the combined influence of warming and elevated pCO2 may have a profound influence on the virus-host dynamics with climate change. More specifically, although climate change may promote cyanobacteria growth, their phages may also be facilitated and thereby pose a stronger control on cyanobacterial bloom formation.

Author Contributions

KC and YJZ had the idea of the experiment. KC was responsible for conducting the experiment together with XYN, and wrote the first manuscript draft with input from all co-authors. DBVDW and KC ran data analyses and wrote the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation of China [grant numbers 31200385, 31370148].

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Li Renhui from institute of hydrobiology, Chinese academy of sciences, for his advices on experiment.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2017.01096/full#supplementary-material

References

Allen, M. B., and Arnon, D. I. (1955). Studies on nitrogen-fixing blue-green algae. II. the sodium requirement of Anabaena Cylindrica. Physiol. Plantarum 8, 653–660. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1955.tb07758.x

Badger, M. R., Price, G. D., Long, B. M., and Woodger, F. J. (2006). The environmental plasticity and ecological genomics of the cyanobacterial CO2 concentrating mechanism. J. Exp. Bot. 57, 249–265. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eri286

Benedi, V. J., Regue, M., Alberti, S., Camprubi, S., and Tomas, J. M. (1991). Influence of environmental conditions on infection of Klebsiella pneumoniae by two different types of bacteriophages. Can. J. Microbiol. 37, 270–275. doi: 10.1139/m91-042

Bidnenko, E., Chopin, A., Ehrlich, S. D., and Chopin, M.-C. (2009). Activation of mRNA translation by phage protein and low temperature: the case of Lactococcus lactis abortive infection system AbiD1. BMC Mol. Biol. 10:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-10-4

Bratbak, G., Jacobsen, A., Heldal, M., Nagasaki, K., and Thingstad, F. (1998). Virus production in Phaeocystis pouchetii and its relation to host cell growth and nutrition. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 16, 1–9. doi: 10.3354/ame016001

Carey, C. C., Ibelings, B. W., Hoffmann, E. P., Hamilton, D. P., and Brookes, J. D. (2012). Eco-physiological adaptations that favour freshwater cyanobacteria in a changing climate. Water Res. 46, 1394–1407. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2011.12.016

Carreira, C. T., Heldal, M., and Bratbak, G. (2013). Effect of increased pCO2 on phytoplankton–virus interactions. Biogeochemistry 114, 391–397. doi: 10.1007/s10533-011-9692-x

Chen, J. X., Ye, X., Chen, X. P., and Huang, B. G. (2005). Study on extraction of photosynthetic pigments from phytoplankton by organic solvents. Xiamen Daxue Xuebao (Ziran Kexue Ban) 44, 102–106.

Cheng, K., Zhao, Y., Du, X., Zhang, Y., Lan, S., and Shi, Z. (2007). Solar radiation-driven decay of cyanophage infectivity, and photoreactivation of the cyanophage by host cyanobacteria. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 48, 13–18. doi: 10.3354/ame048013

Chu, T. C., Murray, S. R., Hsu, S. F., Vega, Q., and Lee, L. H. (2011). Temperature-induced activation of freshwater Cyanophage AS-1 prophage. Acta Histochem. 113, 294–299. doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2009.11.003

Collins, S., and Bell, G. (2004). Phenotypic consequences of 1,000 generations of selection at elevated CO2 in a green alga. Nature 431, 566–569. doi: 10.1038/nature02945

Currier, T. C., and Wolk, C. P. (1979). Characteristics of Anabaena variabilis influencing plaque formation by cyanophage N-1. J. Bacteriol. 139, 88–92.

Danovaro, R., Corinaldesi, C., Dell'anno, A., Fuhrman, J. A., Middelburg, J. J., Noble, R. T., et al. (2011). Marine viruses and global climate change. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 35, 993–1034. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2010.00258.x

Dempsey, R. M., Carroll, D., Kong, H. M., Higgins, L., Keane, C. T., and Coleman, D. C. (2005). Sau421, a Bcgl-like restriction-modification system encoded by the Staphylococcus aureus quadruple-converting phage phi 42. Microbiology 151, 1301–1311. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27646-0

Durmaz, E., and Klaenhammer, T. R. (2007). Abortive phage resistance mechanism AbiZ speeds the lysis clock to cause premature lysis of phage-infected Lactococcus lactis. J. Bacteriol. 189, 1417–1425. doi: 10.1128/JB.00904-06

Emond, E., Holler, B. J., Boucher, I., Vandenbergh, P. A., Vedamuthu, E. R., Kondo, J. K., et al. (1997). Phenotypic and genetic characterization of the bacteriophage abortive infection mechanism AbiK from Lactococcus lactis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63, 1274–1283.

Field, C. B., Behrenfeld, M. J., Randerson, J. T., and Falkowski, P. (1998). Primary production of the biosphere: integrating terrestrial and oceanic components. Science 282, 237–240. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5374.237

Fiorini, S., Middelburg, J. J., and Gattuso, J. P. (2011). Effects of elevated CO2 partial pressure and temperature on the coccolithophore Syracosphaera pulchra. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 64, 221–232. doi: 10.3354/ame01520

Fu, F. X., Warner, M. E., Zhang, Y., Feng, Y., and Hutchins, D. A. (2007). Effects of increased temperature and CO2 on photosynthesis, growth, and elemental ratios in marine Synechococcus and Prochlorococcus (Cyanobacteria). J. Phycol. 43, 485–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2007.00355.x

Fu, F. X., Zhang, Y., Warmer, M. E., Feng, Y., Sun, J., and Hutchins, D. A. (2008). A comparison of future increased CO2 and temperature effects on sympatric Heterosigma akashiwo and Prorocentrum minimum. Harmful Algae 7, 76–90. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2007.05.006

Fuhrman, J. A. (1999). Marine viruses and their biogeochemical and ecological effects. Nature 399, 541–548. doi: 10.1038/21119

Gao, E. B., Gui, J. F., and Zhang, Q. Y. (2012). A novel cyanophage with a cyanobacterial nonbleaching protein A gene in the genome. J. Virol. 86, 236–245. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06282-11

Gnezda-Meijer, K., Mahne, I., Poljsak-Prijatelj, M., and Stopar, D. (2006). Host physiological status determines phage-like particle distribution in the lysate. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 55, 136–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2005.00008.x

Guimont, C., Henry, P., and Linden, G. (1993). Restriction/modification in Streptococcus thermophilus: isolation and characterization of a type II restriction endonuclease Sth455I. Appl. Microbiol. Biot. 39, 216–220. doi: 10.1007/BF00228609

Hadas, H., Einav, M., Fishov, I., and Zaritsky, A. (1997). Bacteriophage T4 development depends on the physiology of its host Escherichia coli. Microbiology 143, 179–185. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-1-179

Hein, M., and Sand-Jensen, K. (1997). CO2 increases oceanic primary production. Nature 388, 526–527. doi: 10.1038/41457

Holding, J. M., Duarte, C. M., Sanz-Martin, M., Mesa, E., Arrieta, J. M., Chierici, M., et al. (2015). Temperature dependence of CO2-enhanced primary production in the European Arctic Ocean. Nat. Clim. Change. 5, 1079–1082. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2768

Honjo, M., Matsui, K., Ishii, N., Nakanishi, M., and Kawabata, Z. (2007). Viral abundance and its related factors in a stratified lake. Fund. Appl. Limnol. 168, 105–112. doi: 10.1127/1863-9135/2007/0168-0105

Jenkins, C. A., and Hayes, P. K. (2006). Diversity of cyanophages infecting the heterocystous filamentous cyanobacterium Nodularia isolated from the brackish Baltic Sea. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. U. K. 86, 529–536. doi: 10.1017/S0025315406013439

Jover, L. F., Effler, T. C., Buchan, A., Wilhelm, S. W., and Weitz, J. S. (2014). The elemental composition of virus particles: implications for marine biogeochemical cycles. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 12, 519–528. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3289

Kendrick, B. J., DiTullio, G. R., Cyronak, T. J., Fulton, J. M., Van Mooy, B. A., and Bidle, K. D. (2014). Temperature-induced viral resistance in Emiliania huxleyi (Prymnesiophyceae). PLoS ONE 9:e112134. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112134

Kosten, S., Huszar, V. L. M., Bécares, E., Costa, L. S., van Donk, E., Hansson, L.-A., et al. (2012). Warmer climates boost cyanobacterial dominance in shallow lakes. Global Change Biol. 18, 118–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02488.x

Kumar Sarkar, S., Takeda, Y., Kanamaru, S., and Arisaka, F. (2006). Association and dissociation of the cell puncturing complex of bacteriophage T4 is controlled by both pH and temperature. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1764, 1487–1492. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2006.07.007

Labedan, B., and Goldberg, E. B. (1979). Requirement for membrane potential in injection of phage T4 DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 76, 4669–4673. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4669

Larsen, J. B., Larsen, A., Thyrhaug, R., Bratbak, G., and Sandaa, R. A. (2008). Response of marine viral populations to a nutrient induced phytoplankton bloom at different pCO2 levels. Biogeosciences 5, 523–533. doi: 10.5194/bg-5-523-2008

Lof, D., Schillen, K., Jonsson, B., and Evilevitch, A. (2007). Forces controlling the rate of DNA ejection from phage lambda. J. Molecul. Biol. 368, 55–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.01.076

Low-Décarie, E., Jewell, M. D., Fussmann, G. F., and Bell, G. (2013). Long-term culture at elevated atmospheric CO2 fails to evoke specific adaptation in seven freshwater phytoplankton species. Proc. R. Soc. B 280:20122598. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2012.2598

Lürling, M., Eshetu, F., Faassen, E. J., Kosten, S., and Huszar, V. L. M. (2013). Comparison of cyanobacterial and green algal growth rates at different temperatures. Freshwater Biol. 58, 552–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2427.2012.02866.x

Maat, D. S., Crawfurd, K. J., Timmermans, K. R., and Brussaard, C. P. D. (2014). Elevated CO2 and phosphate limitation favor Micromonas pusilla through stimulated growth and reduced viral impact. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80, 3119–3127. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03639-13

Mankiewicz-Boczek, J., Jaskulska, A., Paweczyk, J., Gagala, I., Serwecinska, L., and Dziadek, J. (2016). Cyanophages infection of Microcystis bloom in lowland dam reservoir of Sulejw, Poland. Microb. Ecol. 71, 315–325. doi: 10.1007/s00248-015-0677-5

Miśkiewicz, E., Alexander, G. I., Williams, J. P., Mobashsher, U. K., Stefan, F., and Norman, P. A. H. (2000). Photosynthetic acclimation of the filamentous cyanobacterium, Plectonema boryanum UTEX 485, to temperature and light. Plant Cell Physiol. 41, 767–775. doi: 10.1093/pcp/41.6.767

Mojica, K. D., and Brussaard, C. P. (2014). Factors affecting virus dynamics and microbial host-virus interactions in marine environments. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 89, 495–515. doi: 10.1111/1574-6941.12343

Mueller-Merbach, M., Kohler, K., and Hinrichs, J. (2007). Environmental factors for phage-induced fermentation problems: replication and adsorption of the Lactococcus lactis phage P008 as influenced by temperature and pH. Food Microbiol. 24, 695–702. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2007.04.003

Muller, M. N., Lebrato, M., Riebesell, U., Ramos, J. B. E., Schulz, K. G., Blanco-Ameijeiras, S., et al. (2014). Influence of temperature and CO2 on the strontium and magnesium composition of coccolithophore calcite. Biogeosciences 11, 1065–1075. doi: 10.5194/bg-11-1065-2014

Murray, A. G., and Jackson, G. A. (1992). Viral dynamics: a model of the effects of size, shape, motion and abundance of single-celled planktonic organisms and other particles. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 89, 103–116. doi: 10.3354/meps089103

O'Neil, J. M., Davis, T. W., Burford, M. A., and Gobler, C. J. (2012). The rise of harmful cyanobacteria blooms: the potential roles of eutrophication and climate change. Harmful Algae 14, 313–334. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2011.10.027

Ou, T., Liao, X. Y., Gao, X. C., Xu, X. D., and Zhang, Q. Y. (2015). Unraveling the genome structure of cyanobacterial podovirus A-4L with long direct terminal repeats. Virus Res. 203, 4–9. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2015.03.012

Paerl, H. W., and Huisman, J. (2009). Climate change: a catalyst for global expansion of harmful cyanobacterial blooms. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 1, 27–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2008.00004.x

Paul, C., Matthiessen, B., and Sommer, U. (2015). Warming, but not enhanced CO2 concentration, quantitatively and qualitatively affects phytoplankton biomass. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 528, 39–51. doi: 10.3354/meps11264

Prasad, S. M., Kumar, D., and Zeeshan, M. (2005). Growth, photosynthesis, active oxygen species and antioxidants responses of paddy field cyanobacterium Plectonema boryanum to endosulfan stress. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 51, 115–123. doi: 10.2323/jgam.51.115

Raven, J. A., Cockell, C. S., and De La Rocha, C. L. (2008). The evolution of inorganic carbon concentrating mechanisms in photosynthesis. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 363, 2641–2650. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0020

Samimi, B., and Drews, G. (1978). Adsorption of cyanophage AS-1 to unicellular cyanobacteria and isolation of receptor material from Anacystis nidulans. J. Virol. 25, 164–174.

Sanders, M. E., and Klaenhammer, T. R. (1984). Phage resistance in a phage-insensitive strain of Streptococcus lactis: temperature-dependent phage development and host-controlled phage replication. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 47, 979–985.

Stocker, T., Qin, D. H., Plattner, G. K., Tignor, M. M. B., Allen, S. K., Boschung, J., et al. (2013). Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis: Summary for Policymakers. Cambridge; New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Stucken, K., Koch, R., and Dagan, T. (2013). Cyanobacterial defense mechanisms against foreign DNA transfer and their impact on genetic engineering. Biol. Res. 46, 373–382. doi: 10.4067/S0716-97602013000400009

Sulcius, S., Simoliunas, E., Staniulis, J., Koreiviene, J., Baltrusis, P., Meskys, R., et al. (2015). Characterization of a lytic cyanophage that infects the bloom-forming cyanobacterium Aphanizomenon flos-aquae. FEMS Microb. Ecol. 91, 1–7. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiu012

Suttle, C. A. (1993). “Enumeration and isolation of viruses,” in Handbook of Method in Aquatic Microbial Ecology, ed P. F. Kemp (Boca Raton, FL: Lewis Publishers), 121–134.

Suttle, C. A. (2007). Marine viruses-major players in the global ecosystem. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5, 801–812. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1750

Szekeres, M., Szmidt, A. E., and Torok, I. (1983). Evidence for a restriction/modification-like system in Anacystis nidulans infected by cyanophage AS-1. Eur. J. Biochem. 131, 137–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1983.tb07240.x

Tangney, M., and Fitzgerald, G. F. (2002). AbiA, a lactococcal abortive infection mechanism functioning in Streptococcus thermophilus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68, 6388–6391. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.12.6388-6391.2002

Thompson, L. R., Zeng, Q., Kelly, L., Huang, K. H., Singer, A. U., Stubbe, J., et al. (2011). Phage auxiliary metabolic genes and the redirection of cyanobacterial host carbon metabolism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, E757–E764. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102164108

Tijdens, M., van de Waal, D. B., Slovackova, H., Hoogveld, H. L., and Gons, H. J. (2008). Estimates of bacterial and phytoplankton mortality caused by viral lysis and microzooplankton grazing in a shallow eutrophic lake. Freshwater Biol. 53, 1126–1141. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2427.2008.01958.x

Tomaru, Y., Kimura, K., and Yamaguchi, H. (2014). Temperature alters algicidal activity of DNA and RNA viruses infecting Chaetoceros tenuissimus. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 73, 171–183. doi: 10.3354/ame01713

Traving, S. J., Clokie, M. R., and Middelboe, M. (2014). Increased acidification has a profound effect on the interactions between the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp WH7803 and its viruses. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 87, 133–141. doi: 10.1111/1574-6941.12199

Verspagen, J. M. H., Van de Waal, D. B., Finke, J. F., Visser, P. M., Van Donk, E., and Huisman, J. (2014a). Rising CO2 levels will intensify phytoplankton blooms in eutrophic and hypertrophic lakes. PLoS ONE 9:e104325. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104325

Verspagen, J. M. H., Van de Waal, D. B., Finke, J. F., Visser, P. M., and Jef, H. (2014b). Contrasting effects of rising CO2 on primary production and ecological stoichiometry at different nutrient levels. Ecol. Lett. 17, 951–960. doi: 10.1111/ele.12298

Wacklin, P., Hoffmann, L., and Komárek, J. (2009). Nomenclatural validation of the genetically revised cyanobacterial genus Dolichospermum (RALFS ex BORNET et FLAHAULT) comb. nova. Fottea 9, 59–64. doi: 10.5507/fot.2009.005

Walworth, N. G., Lee, M. D., Fu, F. X., Hutchins, D. A., and Webb, E. A. (2016). Molecular and physiological evidence of genetic assimilation to high CO2 in the marine nitrogen fixer Trichodesmium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113:E7367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1605202113

Weinbauer, M. G. (2004). Ecology of prokaryotic viruses. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 28, 127–181. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2003.08.001

Yoshida, T., Takashima, Y., Tomaru, Y., Shirai, Y., Takao, Y., Hiroishi, S., et al. (2006). Isolation and characterization of a cyanophage infecting the toxic cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 1239–1247. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.2.1239-1247.2006

Zhao, F., Zhang, X., Liang, C., Wu, J., Bao, Q., and Qin, S. (2006). Genome-wide analysis of restriction-modification system in unicellular and filamentous cyanobacteria. Physiol. Genomics 24, 181–190. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00255.2005

Zhou, Q., Gao, Y., Zhao, Y., and Cheng, K. (2015). The effect of elevated carbon dioxide concentration on cyanophage PP multiplication and photoreactivation induced by a wild host cyanobacterium. Acta Ecol. Sin. 35, 11–15. doi: 10.1016/j.chnaes.2014.11.001

Keywords: climate change, cyanobacterial virus, infectivity, one-step growth curve, EOP, common garden experiment

Citation: Cheng K, Van de Waal DB, Niu XY and Zhao YJ (2017) Combined Effects of Elevated pCO2 and Warming Facilitate Cyanophage Infections. Front. Microbiol. 8:1096. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01096

Received: 05 February 2017; Accepted: 30 May 2017;

Published: 13 June 2017.

Edited by:

Petra M. Visser, University of Amsterdam, NetherlandsReviewed by:

Anja Engel, GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel(HZ), GermanyHélène Montanié, University of La Rochelle, France

Copyright © 2017 Cheng, Van de Waal, Niu and Zhao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kai Cheng, chengkaicn@163.com

Yi Jun Zhao, zhaoyj2000@163.com

Kai Cheng

Kai Cheng Dedmer B. Van de Waal

Dedmer B. Van de Waal Xiao Ying Niu2

Xiao Ying Niu2