- 1Key Lab of Molecular Virology, Department of Infectious Diseases, Huashan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai, China

- 2Department of Molecular Microbiology and Immunology, Bloomberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, United States

As dormant phenotypic variants of bacteria, persisters account for many chronic infections affecting human health. Despite numerous studies, the role of small non-coding RNA (sRNA) in bacterial persistence has not been reported. To investigate the role of Hfq-interacting sRNA in persistence, we constructed the deletion mutants of 20 Hfq-interacting sRNAs (RyhB, GcvB, MgrR, RybB, MicF, SgrS, RprA, DicF, SsrS, FnrS, GadY, DsrA, OmrB, ArcZ, RyeB, RydC, OmrA, MicA, MicC, and ChiX) to assess their persistence capacity in uropathogenic Escherichia coli strain UTI89 and identified a new sRNA RyhB being involved in persister formation. The ryhB-knockout mutant had significant defect in persistence to a diverse range of antibiotics (levofloxacin, cefotaxime, gentamicin) and stresses (hyperosmosis, acid, and heat) in both exponential phase and stationary phase. In addition, the effect of RyhB on persistence was synergistic with ppGpp and Fur protein. RNA-Seq analysis indicated that the ryhB-knockout mutant had a hyperactive metabolic state compared with the parent strain. Interestingly, increased adenosine triphosphate (ATP) levels and altered NAD+/NADH ratios were observed in the ryhB-knockout mutant. Our findings represent a new level of persistence regulation via sRNA and may provide novel therapeutic targets for interventions.

Introduction

Persisters represent a small number of metabolically quiescent bacteria that survive exposure to bactericidal drugs and stresses while remaining susceptible to drugs and stresses under appropriate conditions (Lewis, 2010; Zhang, 2014). They are genetically identical to the other cells, but exhibit phenotypic differences (Allison et al., 2011a; Zhang, 2014). The recalcitrance of many chronic and persistent bacterial infections, such as tuberculosis, Lyme disease, urinary tract infections (UTIs), and biofilm infections is associated with the presence of persisters (Blango and Mulvey, 2010; Zhang et al., 2012; Levin et al., 2014; Zhang, 2014; Liu et al., 2016). Thus far, many studies on persistence mechanisms have been performed in Escherichia coli (E. coli), with multiple genes and pathways being identified as involved in persister formation, including toxin-antitoxins (TA), SOS response, and DNA repair, signal transduction, membrane stress, energy production, phosphate metabolism, and protein degradation (Zhang, 2014; Harms et al., 2016). However, these findings indicate that persistence is a very complex phenomenon with redundant mechanisms and that there may be other more important potential mechanisms that remain unknown.

In bacteria, small non-coding RNAs (sRNAs), which are relatively short transcripts (~50–300 nucleotides), regulate a wide range of physiological functions in response to external signals (Wassarman, 2002). sRNAs can act by modulating transcription, translation, mRNA stability, DNA maintenance, or silencing by binding to the untranslated region of target mRNAs (Chabelskaya et al., 2010; Gottesman and Storz, 2011; Sayed et al., 2011). Acting as an sRNA chaperone, the global regulator Hfq, facilitates base-pairing interactions between sRNAs. Hfq can not only function directly on its targets but also function indirectly through base-pairing of sRNAs with target mRNAs (Chao and Vogel, 2010). hfq mutant has been reported to have reduced persister formation capacity upon challenge with ampicillin in E. coli and Salmonella enterica (Kim and Wood, 2010; Papenfort and Vogel, 2010; Hebrard et al., 2012). However, whether the role of Hfq in persistence has anything to do with the Hfq-interacting sRNAs remains unknown.

In order to study the role of the Hfq-interacting sRNAs in persistence, we generated deletion mutants of 20 Hfq-binding sRNAs in uropathogenic E. coli UTI89 strain and assessed their persister phenotypes. Our results provide the first evidence of a role for sRNA in regulating persistence, with implications for developing more effective treatments for persistent infections.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

The bacterial strains used in this study were derivatives of the parent strain UTI89. They were routinely cultured in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (10 g bacto-tryptone, 5 g yeast extract, and 10 g NaCl/L) at 37°C, 200 rpm. Bacterial stock stored at −80°C was transferred into fresh LB medium and grown overnight before being used for persister experiments.

Construction of Deletion Mutants and Overexpression Strains

The deletion mutants of Hfq-dependent sRNAs were constructed using the λ Red recombination system as described by Datsenko and Wanner (2000). Primers used to amplify all knockout-DNA fragments and verify the correct constructs by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) are shown in Supplementary Tables 1, 2. To create double-deletion mutants, the chloramphenicol-resistance gene was removed from plasmid pCP20.

The arabinose-inducible plasmid pBAD202 was used to construct overexpression strains according to previous report (Ma et al., 2010). Primers (F: 5′-CATG CCATGGAAAAGCCAGCACCCGGC-3′ and R: 5′-CCCGGAATTCGCGATCAGGAAGACCCTCG-3′) used for the construction of the plasmid containing the RyhB gene were designed in this study. Genes were amplified with PCR primers, followed by digestion of both the PCR fragments and pBAD202 with the restriction enzymes NcoI and EcoRI (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) and ligation using the T4 DNA ligase (New England Biolabs). The new constructs along with the empty vector, pBAD202, were transformed into parent strain UTI89 for overexpression experiments. The deletion mutants and overexpression strains were verified by DNA sequencing. Arabinose (0.1%) was added to the cultures of overexpression strains to induce the conditional expression after bacterial culture for appropriate time.

Persister Assay

Persister levels were determined by counting the number of colony forming units (CFUs) that grew on LB agar plates as previously described (Ma et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2015). The antibiotics levofloxacin (5 μg/mL), cefotaxime (128 μg/mL), gentamicin (30 μg/mL) were added directly to cultures at the exponential (about 3 h of cultivation, ~108 CFU/mL) or stationary (10 h of cultivation, ~109 CFU/mL) phase unless otherwise stated. Aliquots of the bacterial cultures exposed to antibiotics were incubated at 37°C at different time points and washed in phosphate-buffered saline before plating on LB plates in the absence of antibiotics to determine CFU count.

Susceptibility to Various Stresses

For heat shock, bacteria were placed in a water bath at 55°C for 3 h. For acid stress (pH 3.0) and hyperosmosis (NaCl, 4 M), cultures were washed twice with acid or hyperosmotic LB medium and resuspended in the same column of corresponding LB medium, respectively. Aliquots of the bacterial cultures exposed to various stresses were incubated at 37°C at different time points and washed in phosphate-buffered saline before plating on LB plates in the absence of antibiotics to determine CFU count.

RNA Isolation and Real-Time PCR

Bacteria used for real-time PCR (RT-PCR) analysis were routinely cultured for 10 h in LB medium, followed by centrifugation at 5,000 rpm and 4°C to remove the supernatant. RNA Protect bacteria reagent (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) was added to resuspended cells, and total RNA was isolated from cells using a bacterial RNA kit (Omega Bio-tek, Norcross, GA, USA) according to manufacturer protocol for the real-time PCR experiment. Total RNA was converted to cDNA using the PrimeScript TMRT reagent kit with gDNA Eraser (Takara, Shiga, Japan) according to manufacturer protocol and used as a template to perform real-time PCR on an Applied Biosystems 7500 real-time instrument (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The primers for real-time PCR are listed in Supplementary Table 3. The 16S rRNA gene rrsB was used as the reference gene, and changes in expression were presented as the average of three biological replicates.

RNA-Sequencing

RNA extraction, quality assessment, sequencing, and analysis were performed by Shanghai Biotechnology Corporation (Shanghai, China) using method described previously (Xu et al., 2016). Briefly, total RNA was extracted using an RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen) according to manufacturer protocol, and the RNA integrity number was assessed using an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Qualified total RNA was further purified using an RNA clean XP kit (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA) and a RNase-free DNase set (Qiagen). rRNA removal, fragmentation, synthesis of the second strand, adenylation of 3′ ends, adapter ligation, and amplification were prepared prior to sequencing using an Illumina HiSeq 2500 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Reads were assessed and quantified before mapping to genome of E. coli UTI89.

Determination of Intracellular ATP Concentration

Intracellular ATP concentration was determined according to method described previously (Shan et al., 2017). At the appropriate time points, the BacTiter-Glo microbial cell viability assay kit (Promega) was used following the recommended protocol. Briefly, 100 μL BacTiter-Glo reagent and 100 μL cell-culture medium were mixed in 96-well plates on an orbital shaker and incubated for 5 min, followed by determination of luminescence using the SpectraMax Paradigm multi-mode detection platform (Applied Biosystems). The number of bacteria in the 100 μL cell-culture was also determined at the corresponding time. After that, the luminescence of a single cell was calculated.

Measurement of Intracellular NAD+ and NADH Concentration

Intracellular NAD+ and NADH concentrations were measured according to methods described previously (Vilcheze et al., 2005; Maeda et al., 2017). For NAD+ and NADH extraction, bacteria were cultured to the designed timepoints and harvested by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm at 4°C for 3 min. Using the NAD+/NADH Assay Kit (BioAssay Systems, Hayward, CA, USA), the extraction procedure and measurement were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. The reaction was performed in flat-bottom 96-well plates. The NAD+/NADH concentration ratio was calculated based on the measured values of OD565.

Results

Identification of a New Persister sRNA, RyhB

To explore the role of sRNA in persistence, we constructed the knockout-mutant strains of 20 known Hfq-binding sRNAs (RyhB, GcvB, MgrR, RybB, MicF, SgrS, RprA, DicF, SsrS, FnrS, GadY, DsrA, OmrB, ArcZ, RyeB, RydC, OmrA, MicA, MicC, and ChiX; Mandin and Gottesman, 2010; Kim et al., 2015) in E. coli UTI strain UTI89 and exposed the mutants to bactericidal antibiotic levofloxacin (5 μg/mL) in the stationary phase (cultured for 10 h, ~109 CFU/mL). Among these mutants, the RyhB knockout mutant strain ΔryhB displayed a dramatic decrease in persister levels compared with the parent strain UTI89. Thus, RyhB was selected for further investigation below.

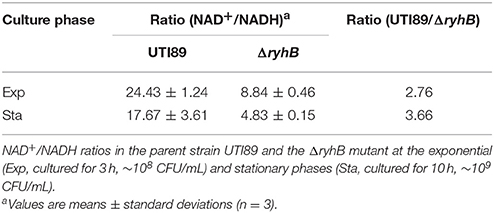

Susceptibilities of the ΔryhB Mutant to a Variety of Antibiotics

To better understand the role of RyhB in persistence, dynamic responses of the ryhB knockout mutant strain ΔryhB and the parent strain UTI89 upon exposure to antibiotics (levofloxacin, cefotaxime, gentamicin) were examined. In the stationary phase (cultured for 10 h, ~109 CFU/mL), the ΔryhB mutant showed ~105-fold lower persister level than the parent strain UTI89 upon treatment with levofloxacin (5 μg/mL) for 5 days (Figure 1A). The case was also applicable to gentamicin and cefotaxime. After gentamicin (30 μg/mL) or cefotaxime (128 μg/mL) treatment for 5 days, the ΔryhB mutant also had lower persister numbers than UTI89, which had a ~104- and ~105-fold decrease, respectively (Figures 1B,C).

Figure 1. Susceptibilities of the ΔryhB mutant to a variety of antibiotics. (A–C). Susceptibilities of the stationary phase bacteria (~109 CFU/mL) were determined every day after exposure to levofloxacin (5 μg/mL, A), gentamicin (30 μg/mL, B) or cefotaxime (128 μg/mL, C). (D) Susceptibilities of the exponential phase bacteria (~108 CFU/mL) were determined after exposure to gentamicin (30 μg/mL) or cefotaxime (128 μg/mL) for 6 h. Error bars show standard variations in CFU between at least three independent experiments.

Because persisters are heterogeneous, and the age of the bacterial culture can affect persister level (Li and Zhang, 2007; Luidalepp et al., 2011; Zhang, 2014), we determined whether RyhB influenced persister level in the exponential phase. Bacteria were cultured for about 3 h to reach the density of ~108 CFU/mL before antibiotics were added. Following gentamicin (30 μg/mL) or cefotaxime (128 μg/mL) exposure, we found the survival of the ΔryhB mutant was decreased (~102- and ~103-fold, respectively) compared with the parent strain (Figure 1D). These results indicate that RyhB was indeed involved in persistence to a wide range of antibiotics in the exponential phase, as well as in the stationery phase.

Furthermore, the ΔryhB mutant displayed a similar defect in persister-formation capacity during the early stationary phase (cultured for 6 h, ~109 CFU/mL) as well as late stationary phase (cultured for 24 h, ~109 CFU/mL) (data not shown).

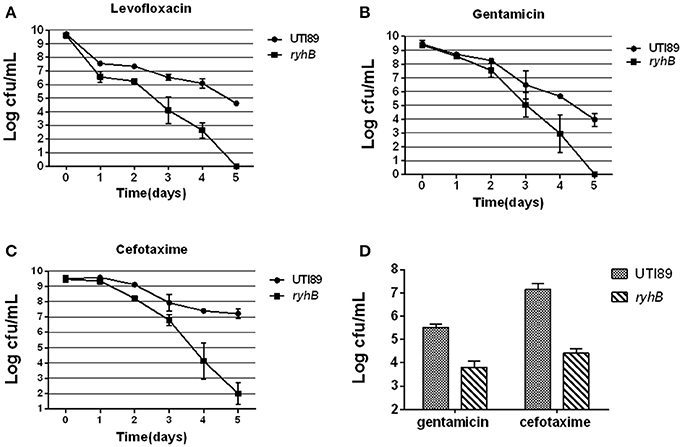

Hypersensitivities of the ΔryhB Mutant to Stresses

To test the effect of stress on the ΔryhB mutant, we subjected the ΔryhB mutant and the parent strain UTI89 to various stresses (hyperosmosis, acid, and heat). In the stationary phase (cultured for 10 h, ~109 CFU/mL), we observed a ~105-fold lower survival of the ΔryhB mutant than the parent strain UTI89 under hyperosmosis (NaCl, 4 M) exposure. In addition, the ΔryhB mutant was also more sensitive to other stresses including heat (55°C) and acid (pH 3.0), with a ~103-fold lower survival to heat, and a ~102-fold lower survival to acid, respectively (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Hypersensitivities of the ΔryhB mutant to stresses. (A) Susceptibilities of the stationary phase bacteria (~109 CFU/mL) were determined after exposure to hyperosmosis (NaCl, 4 M) for 3 d, heat (55°C) for 3 h or acid (pH 3.0) for 12 h. (B) Susceptibilities of the exponential phase bacteria (~108 CFU/mL) were determined after exposure to hyperosmosis (NaCl, 4 M) or acid (pH 3.0) for 3 h. Error bars show standard variations in CFU between at least three independent experiments.

In addition, the effect of stress on the ΔryhB mutant could also be observed in the exponential phase (cultured for about 3 h, ~108 CFU/mL). During hyperosmosis (NaCl, 4 M) or acid (pH 3.0) exposure, the ΔryhB mutant had ~103-fold lower persister numbers than the parent strain UTI89 (Figure 2B).

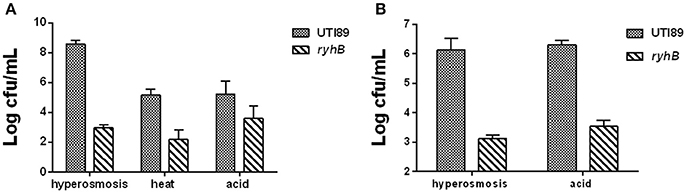

Overexpression of RyhB Confers Higher Persistence Levels

To further determine if RyhB is involved in persister formation, we also overexpressed the RyhB in an inducible vector pBAD202-ryhB transformed into UTI89 and assessed their persister levels. We found a higher persister level in the RyhB overexpression strain than the parent strain carrying the empty vector pBAD202 at each antibiotic (levofloxacin, gentamicin, cefotaxime) and stress (hyperosmosis, heat, acid) we determined (Figure 3). As controls, we also determined the survival of all the strains in our experiments without any treatment, and found no difference at each timepoint (data not shown).

Figure 3. Overexpression of RyhB confers higher persistence levels. (A–C) Susceptibilities to antibiotics levofloxacin (5 μg/mL, A), gentamicin (30 μg/mL, B) or cefotaxime (128 μg/mL, C) at the time points indicated. (D) Susceptibilities to stresses hyperosmosis (NaCl, 4 M), heat (55°C) or acid for 3 d, 3 or 12 h, respectively. Bacteria were cultured to the stationary phase (~109 CFU/mL) prior to the addition of antibiotics or stresses. Error bars show standard variations in CFU between at least three independent experiments.

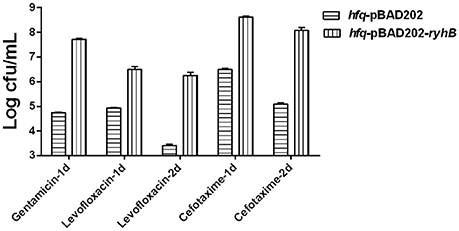

RyhB Confers Persistence Independent of Hfq

To determine whether Hfq was essential for the RyhB-specific persister phenotype, we transformed the RyhB-overexpression vector pBAD202-ryhB or the control empty vector, pBAD202 to an Hfq-knockout strain and subjected them to antibiotic exposure. The initial bacterial numbers were similar before antibiotics were added. The terminal numbers of the group without any treatment were similar too. Our results showed that the ryhB-overexpression strain was more tolerant to antibiotic challenge than the control strain in the absence of Hfq, with a ~103-fold higher count of viable bacteria remaining following gentamicin (30 μg/mL), levofloxacin (5 μg/mL), or cefotaxime (128 μg/mL) exposure (Figure 4). These results suggest that RyhB-related bacterial persistence occurred independent of the Hfq protein. Additionally, we determined the susceptibilities of the Hfq-knockout strain to antibiotic challenge following exposure to gentamicin (30 μg/mL), levofloxacin (5 μg/mL), or cefotaxime (128 μg/mL). Compared with the parent strain, we observed defective persistence in the Hfq-knockout strain following exposure to each antibiotic (data not shown), which is consistent with a previous study (Kim and Wood, 2010).

Figure 4. Effect of RyhB overexpression on persister formation in the hfq-knockout mutant. Antibiotics were added to stationary phase bacteria (~109 CFU/mL) at the appropriate concentrations (gentamicin: 30 μg/mL; levofloxacin: 5 μg/mL; cefotaxime: 128 μg/mL). The number of persisters was counted at the time points indicated in the figure. Error bars show standard variations in CFU between at least three independent experiments. hfq-pBAD202, Hfq-knockout mutant carrying the empty vector pBAD202; hfq-pBAD202-ryhB, Hfq-knockout mutant carrying the ryhB-overexpression vector pBAD202-ryhB.

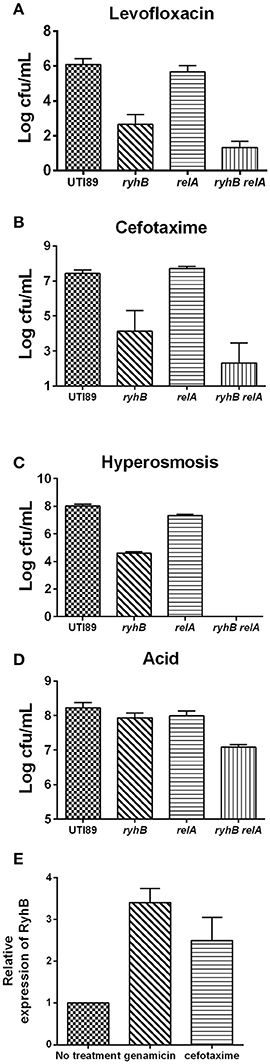

The Effect of RyhB on Persistence is Independent of ppGpp

The first persistence gene, hipA, was shown to depend upon relA-dependent ppGpp synthesis to mediate persistence (Korch et al., 2003; Maisonneuve et al., 2013). To investigate whether RyhB-related persistence is also dependent upon ppGpp, we constructed a relA-deletion mutant, ΔrelA, a RyhB mutant, ΔryhB, and a double-deletion mutant, ΔrelAΔryhB, and measured their persistence to different antibiotics and stresses. We observed that the number of surviving cells of the ΔrelAΔryhB mutant was significantly lower than either of the two single mutants. The number of viable ΔrelAΔryhB mutant cells decreased by ~10-fold following levofloxacin exposure (Figure 5A), ~102-fold following cefotaxime exposure (Figure 5B), ~104-fold during hyperosmotic stress (Figure 5C), and 5-fold upon exposure to acid pH (Figure 5D) as compared with either of the two single-mutant strains. These results indicate that the role of RyhB in persistence is independent of ppGpp, and that deletion of ppGpp further aggravated the persistence phenotype associated with ΔryhB mutant. Interestingly, there was no apparent difference between the ΔrelA mutant and the parent strain following antibiotic exposure, except that the cell number of the ΔrelA mutant decreased 4-fold relative to that of the parent strain under hyperosmostic stress.

Figure 5. RyhB confers persistence in a ppGpp independent manner. ppGpp mutant strain ΔrelA (relA), double-deletion mutant ΔrelAΔryhB (relA ryhB), including the parent UTI89 and RyhB mutant strain ΔryhB (ryhB), were grown to stationary phase (~109 CFU/mL). Exposure pressures and incubation times are shown. (A) Susceptibilities to levofloxacin (5 μg/mL) at day 4. (B) Susceptibilities to cefotaxime (128 μg/mL) at day 4. (C) Susceptibilities to hyperosmosis (NaCl, 4 M) at day 1. (D) Susceptibilities to acid at pH 3.0 at 3 h. (E) Relative expression of RyhB in response to antibiotics. Stationary phase UTI89 bacteria were exposed to gentamicin (30 μg/mL) and cefotaxime (128 μg/mL) for 1 day, followed by extraction of total RNA for real-time PCR. Error bars show standard variations.

To investigate whether this phenomenon is unique to the uropathogenic E. coli UTI89 strain, we constructed a knockout strain, ΔrelA in an E. coli K12 W3110 strain, and evaluated its effect on persistence. Our findings revealed that the W3110 ΔrelA strain exhibited apparent defects in persistence as compared with the parent strain W3110 (data not shown). Therefore, these results indicated that the persistence-related role of relA in uropathogenic E. coli UTI89 differed from that in the E. coli K12 strain.

We then determined ryhB-expression level in the UTI89 strain upon challenging stationary phase bacteria with gentamicin (30 μg/mL) or cefotaxime (128 μg/mL) for 1 day (Figure 5E). Upon antibiotic exposure, we observed higher ryhB-expression levels than that in the untreated strain. The ryhB-expression levels were 3.4- and 2.4-fold relative to that of the parent strain upon exposure to gentamicin and cefotaxime, respectively. These results indicated that RyhB may be induced to protect cells in response to antibiotic stress.

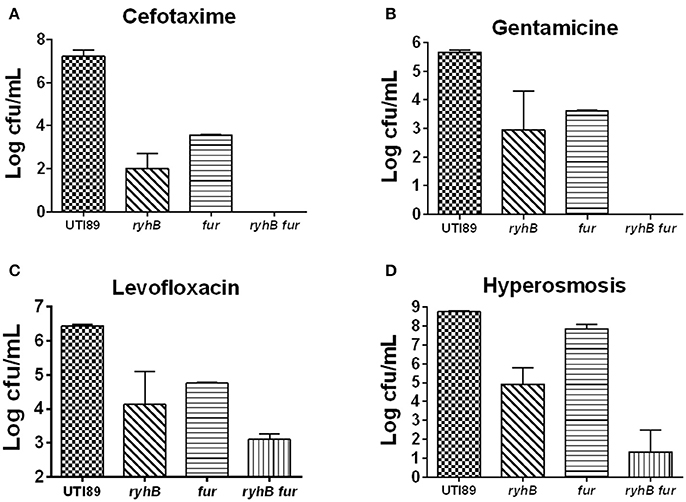

RyhB Is Synergistic with Fur Protein on Persistence

Since RyhB is regulated by the Fur repressor in the presence of iron, we wanted to address the relationship between Fur and RyhB on persistence. To test this, we constructed a single-mutant Δfur strain and a double-mutant ΔryhBΔfur strain. We found that the number of surviving cells of the Δfur mutant was more than 103-fold lower than that in the parent strain upon exposure to cefotaxime (Figure 6A). Furthermore, we observed ~ 102-fold lower viable cells following gentamicin (Figure 6B) or levofloxacin exposure (Figure 6C) and slightly lower levels (about 4-fold) following hyperosmosis (Figure 6D) in the Δfur mutant than the parent strain. These results were contrary to our hypothesis, suggesting that Fur is unable to repress the RyhB-mediated persistence.

Figure 6. The relationship between RyhB and Fur. Fur-mutant strain Δfur (fur), double-deletion mutant ΔryhBΔfur (ryhB fur), including the parent UTI89 and ryhB-mutant strain ΔryhB (ryhB), were cultured for 10 h to the stationary phase prior to the addition of antibiotics or stresses. The types of antibiotics or stresses, as well as incubation times, are annotated. (A) Susceptibilities to cefotaxime (128 μg/mL) at day 5. (B) Susceptibilities to gentamicin (30 μg/mL) at day 4. (C) Susceptibilities to levofloxacin (5 μg/mL) at day 3. (D) Susceptibilities to hyperosmosis (NaCl, 4 M) at day 2. Error bars show standard variations in CFU between at least three independent experiments.

Additionally, we found that the ΔryhBΔfur mutant had >102 times lower CFU than either that of the single-mutants ΔryhB or Δfur following exposure to cefotaxime or gentamicin, as well as hyperosmosis (Figures 6A,B,D). Furthermore, we observed ~10-fold lower cell survival following exposure to levofloxacin (Figure 6C) in the double mutant than that of either of the single mutants. These results indicated that the persister phenotype associated with the ΔryhBΔfur double mutant was more pronounced than that of either of the single ΔryhB or Δfur mutant, suggesting that RyhB exhibits a synergistic effect with Fur in persister formation.

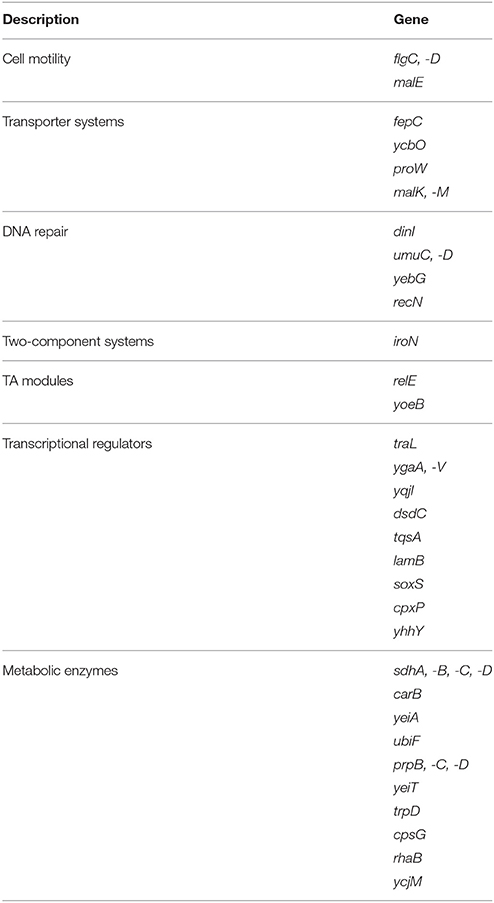

RNA-Seq Analysis Sheds New Light on the Mechanisms of RyhB-Mediated Persistence

Because our data indicated RyhB involvement in persistence, we wanted to investigate how RyhB is involved in persister formation. Therefore, we analyzed genes regulated by RyhB by comparing the ΔryhB mutant and the parent strain UTI89 through RNA-Seq analysis. We found that ~200 genes were upregulated by at least ≥2-fold in the ΔryhB mutant strain, whereas 130 genes were downregulated compared to the parent UTI89 strain. The upregulated genes were mainly comprised of genes belonging to cell motility, transport, toxin-antitoxin modules, DNA repair, transcription, and metabolism (Table 1).

Table 1. Genes upregulated by ≥2-fold in the ryhB-knockout mutant relative to the parent strain UTI89 according to RNA-Seq analysis.

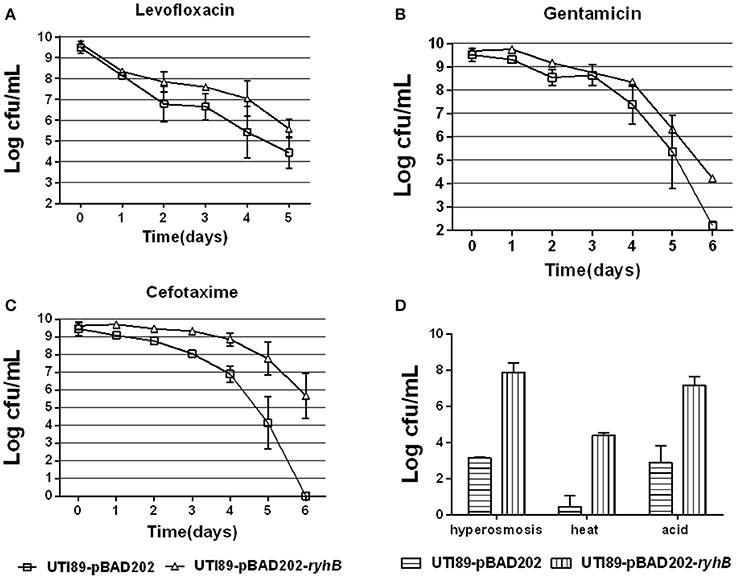

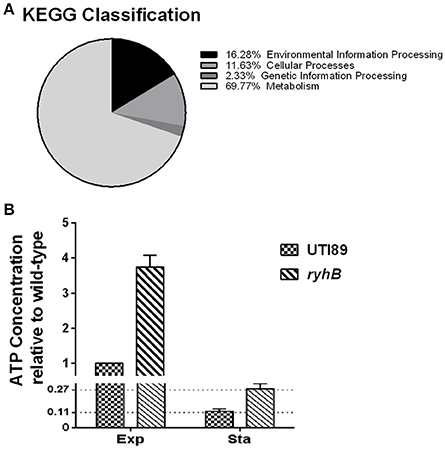

RyhB Deletion Results in a Metabolically Hyperactive State

Among elevated genes in the ΔryhB mutant strain, metabolic genes accounted for ~70% of the total genes according to Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) classification (Figure 7A). For this reason, we hypothesized that the ΔryhB mutant may lead to a metabolically hyperactive state. To test this hypothesis, we determined cellular ATP levels which represent the major energy currency of cells. If the strain is in a metabolically hyperactive state, the ATP level should be high. As expected, the ATP level of the ryhB-knockout strain was over 2-fold higher than that of the parent strain in both exponential and stationary phase cultures (Figure 7B).

Figure 7. The ryhB-knockout mutant causes bacterial transition to a hyperactive metabolic state. (A) KEGG classification of upregulated genes in the ryhB-knockout mutant. Stationary phase bacteria (cultured for 10 h, ~109 CFU/mL) were used for RNA-Seq analysis. (B) Relative ATP concentration in the parent strain UTI89 and the ryhB-knockout mutant at the exponential (Exp, cultured for 3 h, ~108 CFU/mL) and stationary phases (Sta, cultured for 10 h, ~109 CFU/mL). ATP concentration of the parent strain during the exponential phase was considered as 1 unit. Error bars show standard variations (n = 3).

To further confirm that RyhB deletion resulted in a metabolically hyperactive state, intracellular NAD+/NADH ratios were measured (Maeda et al., 2017). We found ΔryhB mutant showed reduced NAD+/NADH ratios in both exponential (2.76-fold decrease) and stationary phase (3.66-fold decrease) cultures (Table 2) when compared with the parent strain. These results indicate that the intracellular environment of the ΔryhB mutant was more reductive compared with the parent strain, suggesting the ΔryhB mutant caused a metabolically hyperactive state.

Discussion

Despite numerous studies investigating the persister phenomenon, the mechanisms of persister formation remain poorly understood. The versatile and complex nature of persister formation prompted us to examine the possible roles of sRNAs in persister formation, given their roles in persistence remain unexplored. In this study, we identified RyhB as a critical sRNA being involved in persister formation for the first time, as mutation in RyhB led to decreased persister numbers to different classes of antibiotics and stresses (Figures 1–3). RNA-Seq analysis indicated that RyhB knockout caused a hyperactive metabolic state, which is confirmed by elevated ATP levels and altered NAD+/NADH ratios in the ryhB-knockout mutant.

RyhB is an important sRNA to regulate iron consumption and storage under Fe2+ depletion conditions through base-pairing mechanism (Masse and Gottesman, 2002). During iron limitation, Fur dissociates from the ryhB operon, leading to the expression of RyhB. RyhB can repress iron-utilizing non-essential mRNA transcription which makes iron available for essential proteins. RyhB can also regulate siderophore production and virulence (Porcheron et al., 2014) and control the redox state of anaerobic metabolism in Enterobacter aerogenes (Wu et al., 2017). In this study, we found that the RyhB-deletion mutant showed defects in persister-formation capacity against antibiotics and stresses (Figures 1–3) and identified a new role for ryhB as a new persister gene. ryhB deletion resulted in upregulation of multiple genes involved in persister-related pathways (Table 1), causing the bacteria to transition to a hyperactive metabolic state. Because cells are more susceptible to antibiotics and stresses in an active metabolic state, RyhB deletion mutant showed defects in persister formation. This finding is reminiscent of our previous observation of the phoU mutant which has a profound defect in persistence and has a hyperactive metabolic state (Li and Zhang, 2007). A previous report showed that metabolic stimulation can be used to eradicate persisters (Allison et al., 2011b), indicating that inhibition of sRNAs (RyhB) might be another alternative method for eliminating persisters. In addition, previous studies showed ATP depletion can suppress the activities of antibiotic targets facilitating persister formation (Conlon et al., 2016; Shan et al., 2017). Our finding of RyhB mutation causing defect in persisters with elevated ATP production is consistent with this observation in E. coli.

Hfq protein is known to regulate sRNAs in many bacteria. This protein can protect sRNAs from degradation and prompt sRNA to match with targets (Updegrove et al., 2016). However, in our study, we found the persister role of RyhB was independent of Hfq. The strain harboring Hfq protein did have a higher persister level than the strain without Hfq protein when RyhB was overexpressed (Figures 3, 4). In the absence of Hfq, the overexpression of RyhB could also cause increased persister level (Figure 4). This indicates that RyhB involvement in persistence is not dependent on Hfq. This is consistent with the previous study that showed RyhB could also regulate target SodB in Hfq deletion background (Geissmann and Touati, 2004).

As a major stringent-response regulator of E. coli K12, RelA represents the primary ppGpp synthetase, whose deficiency generates fewer persister cells (Korch et al., 2003). In our study, we did not observe a significant difference between the ΔrelA mutant and the parent strain UTI89 (Figure 5). This might have been due to the following possibilities: (1) the function of relA in the UTI89 strain might not be similar with that of E. coli K12 strains. Because we found that there are 49 nucleotide differences in the relA sequences between the clinical UTI89 strain and the laboratory E. coli K12 stains. (2) As a clinical UTI strain, UTI89 is more tolerant to external adverse environments than laboratory E. coli K12 strains. For example, deletion of rpoE in the UTI89 strain was not as lethal as in laboratory E. coli K12 strains (Button et al., 2007). Additionally, the UTI89 strain showed greater tolerance to reactive oxygen species and reactive nitrogen species than E. coli K12 strains (Rama et al., 2005; Kulesus et al., 2008). In this study, the ΔrelAΔryhB double mutant showed more obvious persister defect phenotype than either of the single mutant. This observation indicates that RelA exhibited a synergic effect with RyhB in persister formation, which is consistent with the previous observation that RelA protein stimulated the RyhB activity (Argaman et al., 2012).

In summary, this study represents the first report demonstrating that sRNA plays important roles in persister formation using a clinically relevant uropathogenic strain of E. coli UTI89. The sRNA RyhB plays a major role in persistence in a manner that is independent of the sRNA-binding protein Hfq, but synergistic with the ppGpp and Fur proteins. Further studies are needed to determine whether sRNA RyhB is involved in in vivo persistence in animal models. Because sRNAs represent a quick and efficient way to regulate gene expression without protein synthesis, they could play a versatile role in rapid persister formation in response to environmental stresses or antibiotic exposure. Our findings expand the current understanding of mechanisms of persistence to the sRNA level and may have implications for developing improved treatment of persistent bacterial infections.

Author Contributions

YZ and WZ designed the experiments; SZ and SL completed all the experiments, SZ, NW and YY performed the data analysis; SZ and YZ wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Peng Cui, Tao Xu, Jing Wu, and Jiazhen Chen, Department of Infectious Diseases, Huashan Hospital for advice in analysis of RNA-Seq data. The research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81572046 and 81772231).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2018.00136/full#supplementary-material

References

Allison, K. R., Brynildsen, M. P., and Collins, J. J. (2011a). Heterogeneous bacterial persisters and engineering approaches to eliminate them. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 14, 593–598. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2011.09.002

Allison, K. R., Brynildsen, M. P., and Collins, J. J. (2011b). Metabolite-enabled eradication of bacterial persisters by aminoglycosides. Nature 473, 216–220. doi: 10.1038/nature10069

Argaman, L., Elgrably-Weiss, M., Hershko, T., Vogel, J., and Altuvia, S. (2012). RelA protein stimulates the activity of RyhB small RNA by acting on RNA-binding protein Hfq. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 4621–4626. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113113109

Blango, M. G., and Mulvey, M. A. (2010). Persistence of uropathogenic Escherichia coli in the face of multiple antibiotics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54, 1855–1863. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00014-10

Button, J. E., Silhavy, T. J., and Ruiz, N. (2007). A suppressor of cell death caused by the loss of sigma(E) downregulates extracytoplasmic stress responses and outer membrane vesicle production in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 189, 1523–1530. doi: 10.1128/JB.01534-06

Chabelskaya, S., Gaillot, O., and Felden, B. (2010). A Staphylococcus aureus small RNA is required for bacterial virulence and regulates the expression of an immune-evasion molecule. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1000927. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000927

Chao, Y. J., and Vogel, J. (2010). The role of Hfq in bacterial pathogens. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 13, 24–33. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2010.01.001

Conlon, B. P., Rowe, S. E., Gandt, A. B., Nuxoll, A. S., Donegan, N. P., Zalis, E. A., et al. (2016). Persister formation in Staphylococcus aureus is associated with ATP depletion. Nat. Microbiol. 1:16051. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.51

Datsenko, K. A., and Wanner, B. L. (2000). One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297

Geissmann, T. A., and Touati, D. (2004). Hfq, a new chaperoning role: binding to messenger RNA determines access for small RNA regulator. EMBO J. 23, 396–405. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600058

Gottesman, S., and Storz, G. (2011). Bacterial small RNA regulators: versatile roles and rapidly evolving variations. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 3:a003798. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003798

Harms, A., Maisonneuve, E., and Gerdes, K. (2016). Mechanisms of bacterial persistence during stress and antibiotic exposure. Science 354:aaf4268. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf4268

Hébrard, M., Kröger, C., Srikumar, S., Colgan, A., Händler, K., and Hinton, J. C. (2012). sRNAs and the virulence of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. RNA Biol. 9, 437–445. doi: 10.4161/rna.20480

Kim, T., Bak, G., Lee, J., and Kim, K. S. (2015). Systematic analysis of the role of bacterial Hfq-interacting sRNAs in the response to antibiotics. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 70, 1659–1668. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv042

Kim, Y., and Wood, T. K. (2010). Toxins Hha and CspD and small RNA regulator Hfq are involved in persister cell formation through MqsR in Escherichia coli. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 391, 209–213. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.11.033

Korch, S. B., Henderson, T. A., and Hill, T. M. (2003). Characterization of the hipA7 allele of Escherichia coli and evidence that high persistence is governed by (p)ppGpp synthesis. Mol. Microbiol. 50, 1199–1213. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03779.x

Kulesus, R. R., Diaz-Perez, K., Slechta, E. S., Eto, D. S., and Mulvey, M. A. (2008). Impact of the RNA chaperone Hfq on the fitness and virulence potential of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 76, 3019–3026. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00022-08

Levin, B. R., Concepcion-Acevedo, J., and Udekwu, K. I. (2014). Persistence: a copacetic and parsimonious hypothesis for the existence of non-inherited resistance to antibiotics. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 21, 18–21. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2014.06.016

Lewis, K. (2010). Persister cells. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 64, 357–372. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134306

Li, Y., and Zhang, Y. (2007). PhoU is a persistence switch involved in persister formation and tolerance to multiple antibiotics and stresses in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51, 2092–2099. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00052-07

Liu, S. C., Han, X. M., Shi, M., and Pang, Z. L. (2016). Persistence of uropathogenic Escherichia coli in the bladders of female patients with sterile urine after antibiotic therapies. J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Technol. Med. Sci. 36, 710–715. doi: 10.1007/s11596-016-1649-9

Luidalepp, H., Jõers, A., Kaldalu, N., and Tenson, T. (2011). Age of inoculum strongly influences persister frequency and can mask effects of mutations implicated in altered persistence. J. Bacteriol. 193, 3598–3605. doi: 10.1128/JB.00085-11

Ma, C., Sim, S. Z., Shi, W. L., Du, L. J., Xing, D. M., and Zhang, Y. (2010). Energy production genes sucB and ubiF are involved in persister survival and tolerance to multiple antibiotics and stresses in Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 303, 33–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01857.x

Maeda, S., Shimizu, K., Kihira, C., Iwabu, Y., Kato, R., Sugimoto, M., et al. (2017). Pyruvate dehydrogenase complex regulator (PdhR) gene deletion boosts glucose metabolism in Escherichia coli under oxygen-limited culture conditions. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 123, 437–443. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2016.11.004

Maisonneuve, E., Castro-Camargo, M., and Gerdes, K. (2013). (p)ppGpp controls bacterial persistence by stochastic induction of toxin-antitoxin activity. Cell 154, 1140–1150. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.048

Mandin, P., and Gottesman, S. (2010). Integrating anaerobic/aerobic sensing and the general stress response through the ArcZ small RNA. EMBO J. 29, 3094–3107. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.179

Masse, E., and Gottesman, S. (2002). A small RNA regulates the expression of genes involved in iron metabolism in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 4620–4625. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032066599

Papenfort, K., and Vogel, J. (2010). Regulatory RNA in bacterial pathogens. Cell Host Microbe 8, 116–127. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.06.008

Porcheron, G., Habib, R., Houle, S., Caza, M., Lépine, F., Daigle, F., et al. (2014). The small RNA RyhB contributes to siderophore production and virulence of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 82, 5056–5068. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02287-14

Rama, G., Chhina, D. K., Chhina, R. S., and Sharma, S. (2005). Urinary tract infections - microbial virulence determinants and reactive oxygen species. Compar. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 28, 339–349. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2005.09.002

Sayed, N., Jousselin, A., and Felden, B. (2011). A cis-antisense RNA acts in trans in Staphylococcus aureus to control translation of a human cytolytic peptide. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 19, 105–112. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2193

Shan, Y., Gandt, A. B., Rowe, S. E., Deisinger, J. P., Conlon, B. P., and Lewis, K. (2017). ATP-dependent persister formation in Escherichia coli. Mbio 8:e02267–16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02267-16

Updegrove, T. B., Zhang, A. X., and Storz, G. (2016). Hfq: the flexible RNA matchmaker. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 30, 133–138. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2016.02.003

Vilchèze, C., Weisbrod, T. R., Chen, B., Kremer, L., Hazbón, M. H., Wang, F., et al. (2005). Altered NADH/NAD(+) ratio mediates coresistance to isoniazid and ethionamide in mycobacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49, 708–720. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.2.708-720.2005

Wang, W. J., Chen, J. Z., Chen, G., Du, X., Cui, P., Wu, J., et al. (2015). Transposon mutagenesis identifies novel genes associated with Staphylococcus aureus persister formation. Front. Microbiol. 6:1437. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01437

Wassarman, K. M. (2002). Small RNAs in bacteria: diverse regulators of gene expression in response to environmental changes. Cell 109, 141–144. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00717-1

Wu, Y., Hao, Y., Wei, X., Shen, Q., Ding, X., Wang, L., et al. (2017). Impairment of NADH dehydrogenase and regulation of anaerobic metabolism by the small RNA RyhB and NadE for improved biohydrogen production in Enterobacter aerogenes. Biotechnol. Biofuels 10:248. doi: 10.1186/s13068-017-0938-2

Xu, T., Han, J., Zhang, J., Chen, J., Wu, N., Zhang, W., et al. (2016). Absence of protoheme IX farnesyltransferase CtaB causes virulence attenuation but enhances pigment production and persister survival in MRSA. Front. Microbiol. 7:1625. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01625

Zhang, Y. (2014). Persisters, persistent infections and the Yin-Yang model. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 3:e3. doi: 10.1038/emi.2014.3

Keywords: Escherichia coli, persisters, small RNA, RyhB, metabolism, ATP, NAD+/NADH, antibiotics

Citation: Zhang S, Liu S, Wu N, Yuan Y, Zhang W and Zhang Y (2018) Small Non-coding RNA RyhB Mediates Persistence to Multiple Antibiotics and Stresses in Uropathogenic Escherichia coli by Reducing Cellular Metabolism. Front. Microbiol. 9:136. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00136

Received: 10 October 2017; Accepted: 22 January 2018;

Published: 06 February 2018.

Edited by:

Hao Shen, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, United StatesReviewed by:

Mario M. D'Elios, University of Florence, ItalyMaryam Dadar, Razi Vaccine and Serum Research Institute, Iran

Jianping Xie, Southwest University, China

Copyright © 2018 Zhang, Liu, Wu, Yuan, Zhang and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wenhong Zhang, zhangwenhong@fudan.edu.cn

Ying Zhang, yzhang@jhsph.edu

Shanshan Zhang1

Shanshan Zhang1 Wenhong Zhang

Wenhong Zhang Ying Zhang

Ying Zhang