Altered Functional Connectivity of the Basal Nucleus of Meynert in Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Resting-State fMRI Study

- 1Department of Radiology, Xuanwu Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China

- 2Beijing Key Lab of MRI and Brain Informatics, Beijing, China

- 3Department of Psychiatry, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, USA

- 4Department of Neuroscience, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, USA

- 5Beijing Huilongguan Hospital, Beijing, China

Background: Cholinergic dysfunction plays an important role in mild cognitive impairment (MCI). The basal nucleus of Meynert (BNM) provides the main source of cortical cholinergic innervation. Previous studies have characterized structural changes of the cholinergic basal forebrain in individuals at risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease (AD). However, whether and how functional connectivity of the BNM (BNM-FC) is altered in MCI remains unknown.

Objective: The aim of this study was to identify alterations in BNM-FC in individuals with MCI as compared to healthy controls (HCs), and to examine the relationship between these alterations with neuropsychological measures in individuals with MCI.

Method: One-hundred-and-one MCI patients and 103 HCs underwent resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI). Imaging data were processed with SPM8 and CONN software. BNM-FC was examined via correlation in low frequency fMRI signal fluctuations between the BNM and all other brain voxels. Group differences were examined with a covariance analysis with age, gender, education level, mean framewise displacement (FD) and global correlation (GCOR) as nuisance covariates. Pearson’s correlation was conducted to evaluate the relationship between the BNM-FC and clinical assessments.

Result: Compared with HCs, individuals with MCI showed significantly decreased BNM-FC in the left insula extending into claustrum (insula/claustrum). Furthermore, greater decrease in BNM-FC with insula/claustrum was associated with more severe impairment in immediate recall during Auditory Verbal Learning Test (AVLT) in MCI patients.

Conclusion: MCI is associated with changes in BNM-FC to the insula/claustrum in relation to cognitive impairments. These new findings may advance research of the cholinergic bases of cognitive dysfunction during healthy aging and in individuals at risk of developing AD.

Introduction

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI), as a syndrome of cognitive decline without demonstrable alteration in daily activities (Gauthier et al., 2006), frequently precedes the development of Alzheimer’s disease (AD; Petersen, 2011). Epidemiological studies reveal that 3% to 19% of the adults older than 65 years of age suffer from MCI (Gauthier et al., 2006). Most of the patients with MCI experience poor memory as the primary symptom (Kawas, 2003). Memory formation and maintenance is supported by a wide swath of cerebral structures and endogenous acetylcholine plays a critical role in the modulation of information acquisition, encoding, consolidation and retrieval (Blokland et al., 1992; Boccia et al., 2003, 2004, 2009; Power et al., 2003; Winters and Bussey, 2005). As the most important component of the basal forebrain cholinergic system (BFCS; Liu et al., 2015), the basal nucleus of Meynert (BNM) provides main sources of cholinergic innervation to the cerebral cortex (Gratwicke et al., 2013). In MCI, β-amyloid (Aβ) deposition, neurofibrillary tangles and trophic support reduction impair cholinergic functions of the BNM (Mesulam et al., 1986; Ruberg et al., 1990; Vogels et al., 1990). It is plausible that dysfunctional BNM-FC may contribute to cognitive decline in patients with MCI (Whitehouse et al., 1981; Mesulam et al., 1983; Nordberg, 1993; Cullen et al., 1997; Grothe et al., 2010; Ferreira-Vieira et al., 2016).

In humans the BNM is located in the BFCS with an extent of approximately 13–14 mm anterio-posteriorly and 16–18 mm medio-laterally (Gratwicke et al., 2013). The small volume and irregular border has impeded research of the BNM. Extant imaging studies have focused on volume changes in the BNM in association with MCI (Hanyu et al., 2002; Zaborszky et al., 2008; Grothe et al., 2012) with reduced volume extending into the whole BFCS in patient with AD (George et al., 2011; Grothe et al., 2013, 2014), as compared with healthy aging (Kilimann et al., 2014). For instance, volume reduction of the BNM and temporal lobe structures was associated with impairment in delayed recall in MCI patients (Grothe et al., 2010). These findings are consistent with neuronal loss in the BNM during the prodromal stage of AD and greater neuronal loss in the BNM than other cortical and subcortical structures in advanced AD (Arendt et al., 2015).

Investigators have suggested that functional alterations likely precede structural atrophy and examination of cerebral functional connectivity may be critical to understanding the etiologies of many neuropsychiatric disease (Greicius et al., 2004; Fox and Raichle, 2007; Qi et al., 2010; Liang et al., 2011). Low-frequency fluctuations of blood oxygenation level–dependent (BOLD) signal that occur during rest reflect connectivity between functionally related brain regions (Biswal et al., 1995; Fair et al., 2007; Fox and Raichle, 2007). Studies of this “spontaneous” activity describe the intrinsic functional architecture of the sensory, motor, cognitive systems (Fox and Raichle, 2007; Manza et al., 2015; Kann et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2016) and may provide useful information on network functional integrity. For instance, numerous studies have demonstrated altered resting state functional connectivity (rsFC) in patients with MCI and AD (Wang et al., 2006; Sorg et al., 2007; Liang et al., 2012). Compared with healthy controls (HCs), selected areas of the default mode network, including the posterior cingulate, and the executive attention network demonstrated reduced network-related activity in individuals with MCI (Sorg et al., 2007). Patients with mild AD demonstrated disruption in hippocampal connectivity to the medial prefrontal cortex, ventral anterior cingulate cortex, posterior cingulate cortex, right superior and middle temporal gyrus (Wang et al., 2006). The network dysconnectivity appears to aggravate as the illness progresses.

On the other hand, whether or how BNM-FC is altered in MCI or AD remains unknown. On the basis of a previous study that delineated the BNM of post-mortem human brains in a standard stereotaxic space (Zaborszky et al., 2008), we recently characterized whole-brain rsFC of the BNM in a large cohort of healthy adults (Li et al., 2014). Furthermore, we showed that BNM connectivity to the visual and somatomotor cortices decreases while connectivity to subcortical structures including the midbrain, thalamus and pallidum increases with age (Li et al., 2014). These findings of age-related changes of cerebral functional connectivity of the BNM may facilitate research of the neural bases of cognitive decline in health and illness. Here, we pursued this issue by investigating whole-brain rsFC of the BNM in individuals with MCI. We hypothesized that, in comparison with age-matched control participants, BNM connectivity with cortical-subcortical regions would be disrupted in MCI patients in association with cognitive dysfunction.

Materials and Methods

Subjects and Assessments

One-hundred and one MCI patients were recruited from the Xuanwu Hospital of Capital Medical University in Beijing. MCI patients met the core clinical criteria stipulated by the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association (Albert et al., 2011) that include: (a) complaint of a change in cognition; (b) impairment in cognitive function, especially episodic memory; (c) ability to maintain independence in daily activities; (d) not demented; and (e) Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) score = 0.5, with a score of at least 0.5 on the memory domain (Petersen et al., 2001).

One-hundred and three age- and gender-matched HCs were recruited from the community for comparison. The criteria for the HCs was as follows: (a) no current or previous diagnosis of any neurological or psychiatric disorders; (b) no neurological deficiencies in physical examinations; (c) absence of abnormal findings on brain MRI; (d) no complaints of cognitive changes; and (e) a CDR score of 0. Additional exclusion criteria for both MCI and HCs participants included contraindications for MRI such as use of cardiac pacemakers and claustrophobia.

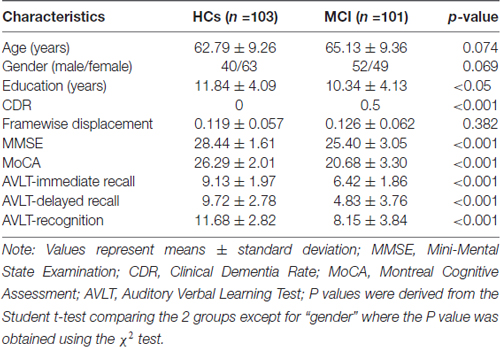

All participants underwent history-taking, complete physical examination and neuropsychological evaluation with Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), CDR, Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) and Auditory Verbal Learning Test (AVLT). MMSE has been a widely used cognitive test (Nilsson, 2007) since its publication in 1975 (Folstein et al., 1975), with excellent sensitivity and moderate specificity in the diagnosis of dementia in specialist settings (Mitchell, 2009). MoCA is a brief, stand-alone cognitive screening tool with high sensitivity and specificity for the detection of MCI and excellent test-retest reliability (Nasreddine et al., 2005). CDR is used to stage the severity of AD in longitudinal studies and clinical trials covering six cognitive categories, including memory, orientation, judgment and problem solving, community affairs, home and hobbies and personal care (Morris, 1993). AVLT provides a standardized procedure to evaluate verbal learning and memory of supra-span lists of words (Volkmar, 2013) and has been proved to be useful in the diagnosis of MCI and could predict disease progression (Zhao Q. et al., 2015). Demographic and assessment data of the participants are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of the mild cognitive impairment (MCI) patients and healthy controls (HCs).

The study was conducted under a research protocol approved by the Ethics Committee of the Xuanwu Hospital, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants were given a detailed explanation of the study and signed an informed consent prior to the study.

MRI Data Acquisition

MRI data were acquired with a 3-Tesla Trio scanner (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). All participants were asked to hold still, with their eyes closed. Foam padding was employed to limit head motion and headphones were used to reduce scanner noise. Resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI) images were acquired using an echo-planar imaging (EPI) sequence with a repetition time (TR)/echo time (TE)/flip angle (FA) = 2000 ms/40 ms/90, field of view (FOV) = 256 mm, 28 axial slices, slice thickness/gap = 4/1 mm, bandwidth = 2232 Hz/pixel and number of repetitions = 239. The 3D T1-weighted anatomical image was acquired with a magnetization-prepared rapid gradient echo (MPRAGE) method with the following parameters: TR/TE/inversion time (TI)/FA = 1900 ms/2.2 ms/900 ms/9, bandwidth = 199 mm, matrix = 256 × 224, 176 sagittal slices with 1 mm thickness.

MRI Data Preprocessing and Functional Connectivity Analysis

Rs-fMRI data were preprocessed using the statistical parametric mapping software SPM8 (Wellcome Department of Imaging Neuroscience, London, UK) and seed-to-voxel correlation analysis was carried out by the functional connectivity (CONN) toolbox v17a (Whitfield-Gabrieli and Nieto-Castanon, 2012). The first 10 functional images were discarded to reduce the fluctuation of MRI signal in the initial stage of scanning. The remaining 229 images of each individual subject were first corrected for slice timing to reduce the within-scan acquisition time differences between slices and then realigned to eliminate the influence of head motion during the experiment. All subjects included in the present study exhibited head motion less than 1.5 mm in any of the x, y, or z directions and less than 1.5° of any angular dimension and volume-level mean framewise displacement (FD) less than 0.30 (with a mean FD across all subjects of 0.12 ± 0.06; Power et al., 2012). Next, the realigned images were spatially normalized to the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space and resampled them to 2 × 2 × 2 mm3. Subsequently, the functional images were smoothed with a 4-mm full width at half maximum (FWHM) isotropic Gaussian kernel. After preprocessing, images were then band-pass filtered to 0.008 ~0.09 Hz to reduce the influence of noise. Further denoising steps included regression of the six motion parameters and their first-order derivatives, regression of white matter and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) signals following the implemented CompCor strategy (Behzadi et al., 2007) and a linear detrending. In second-level covariance analysis, the covariates included age, gender, education level, mean FD (Power et al., 2015), as well as global correlation (GCOR; Saad et al., 2013). Localization of brain region was conducted with xjView1.

The seed BNM was, as defined by Li et al. (2014), based on a stereotaxic probabilistic maps of the basal forebrain, that contains the magnocellular cholinergic corticopetal projection neurons (Zaborszky et al., 2008). In the latter study, after a T1-weighted MRI scan, 10 human postmortem brains were made into histological serial sections and stained by silver. The positions and the extent of each part of the basal forebrain were microscopically delineated, 3D reconstructed and warped to the reference space of the MNI brain. Magnocellular cell groups in the subcommissural-sublenticular region of the basal forebrain were defined as the BNM (Vogels et al., 1990; de Lacalle et al., 1991). To consider the influence of volumetric difference in BNM between patients with MCI and HCs, we compared gray matter volume of BNM between MCI and HCs groups.

The correlation coefficients between the seed voxels and all other brain voxels were computed to generate correlation maps. For group analyses the correlation coefficients were converted to z-value using Fisher’s r-to-z transformation to improve normality (Lowe et al., 1998).

Statistical Analysis

Clinical data and neuropsychological measures were analyzed using SPSS 19, with the Student’s t-test conducted for continuous variables and the chi-squared test for dichotomous variables. The BNM-FC maps were analyzed based on a voxel-wise comparison across the whole brain. The individual z value was entered into a random effect one sample t-test to determine brain regions showing significant connectivity to the BNM within each group. Results within-group were thresholded at voxel-level p < 0.05 (FWE corrected) and cluster size >100 voxels. Two-sample t-test was performed to compare BNM-FC between MCI and HCs with age, gender, education level, mean FD, as well as GCOR as nuisance covariables. For between-group comparisons, we used 3dClustSim program in AFNI (version: December 8, 20162) to conduct the multiple comparison corrections within a group GM mask (obtained by a threshold of 0.2 on the mean GM probability map of all subjects) using a voxel-wise threshold of p < 0.0005 (uncorrected) and cluster size >69 voxels, which corresponded to a corrected p < 0.05 (using AFNI’s updated autocorrelation function estimation; Cox et al., 2017).

Correlation Analysis

Region-of-interest (ROI) analysis was performed on the regions showing significant BNM-FC changes in MCI as compared to HCs. For each subject the mean BNM-FC across all voxels of each ROI was extracted and computed. Partial correlation analysis was then conducted to evaluate the relationship between the BNM-FC to these ROIs and raw scores of clinical assessments, controlled for age, gender, education level, mean FD, as well as GCOR. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05, Bonferroni corrected for multiple comparisons.

Results

Demography and Neuropsychological Assessment

As shown in Table 1, no significant difference in age, gender and FD was found between the patients with MCI and HCs. Compared to HCs, MCI patients showed significantly lower education level (p < 0.05) and cognitive decline in the MMSE (p < 0.001), MoCA (p < 0.001) and AVLT (p < 0.001) score. Meanwhile, MCI patients showed significantly higher CDR score, as compared with HCs (p < 0.001).

Whole Brain BNM-FC in HCs and MCI Patients

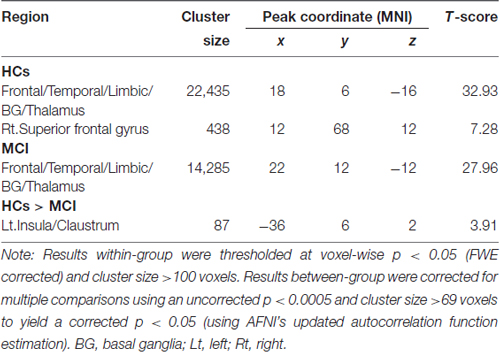

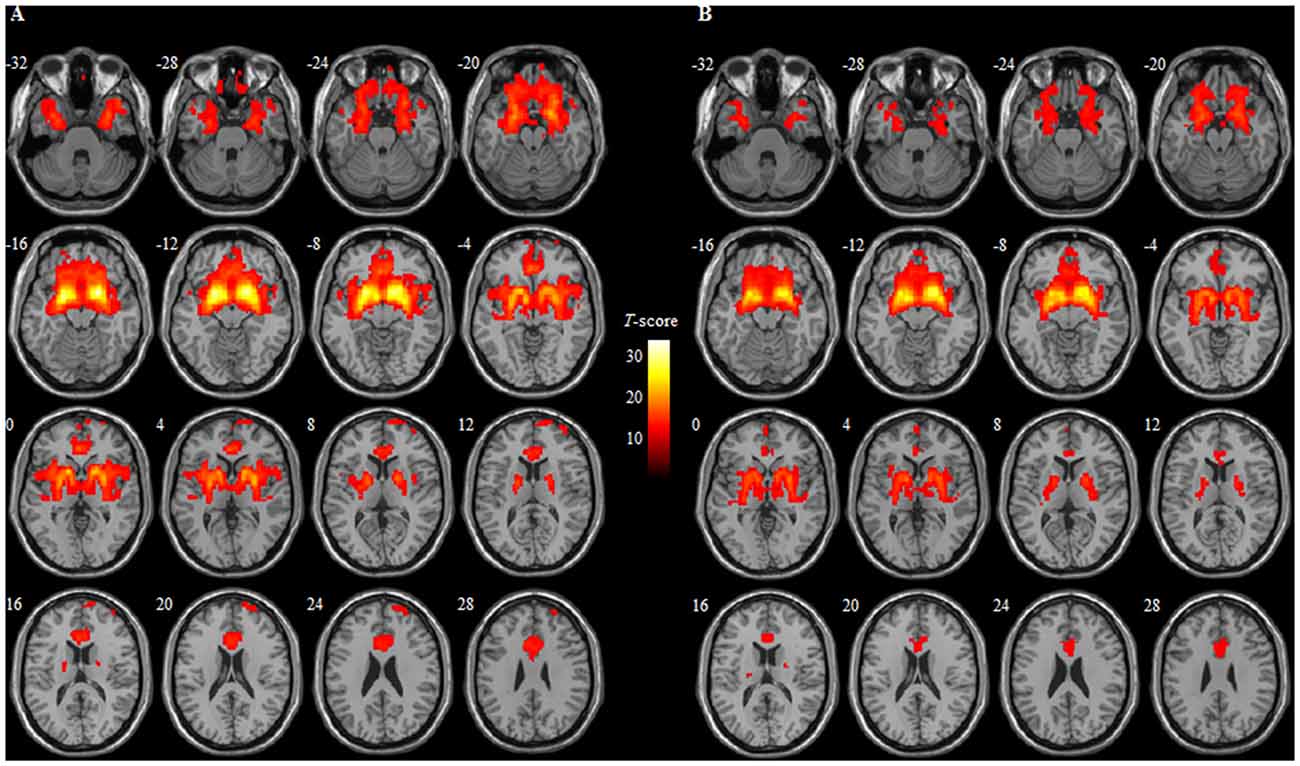

Within group analysis revealed that the positive connectivity between the BNM and many brain regions both in HCs and individuals with MCI. These regions included the bilateral frontal lobe extending into the orbital/rectal cortex, medial/inferior/middle gyrus, temporal lobe extending into (para) hippocampus/amygdala, basal ganglia including the caudate/putamen/claustrum, as well as thalamus (Table 2 and Figure 1).

Table 2. Regions of basal nucleus of Meynert-functional connectivity (BNM-FC) from one-sample t test of each group and regions showing decreased BNM-FC in MCI as compared to HCs.

Figure 1. Whole brain functional connectivity of the basal nucleus of Meynert (BNM) in healthy controls (HCs) (A) and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) (B). Numbers in the figure indicate the Z coordinate in Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI); results within-group were thresholded at voxel-wise p < 0.05 (FWE corrected) and cluster size >100 voxels. BNM, basal nucleus of Meynert; colorbar indicates t-score.

Altered BNM-FC in MCI Patients Compared to HCs

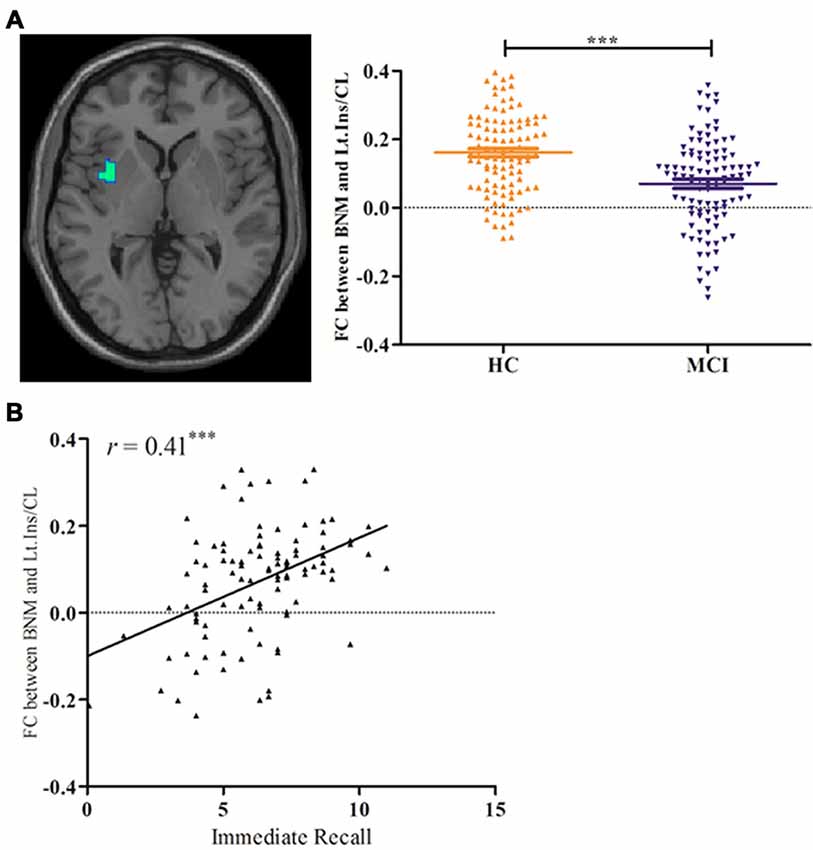

Compared with HCs, significantly decreased BNM-FC was detected in the left insula/claustrum in MCI patients (Figure 2A and Table 2). No brain regions showed increased BNM-FC in MCI patients when compared to HCs. In addition, no significant difference was observed in the gray matter volume of BNM between MCI and HCs (p = 0.067).

Figure 2. (A) Decreased BNM-left insula/claustrum connectivity in MCI patients; and (B) linear correlation of BNM-left insula/claustrum connectivity and AVTL-immediate recall performance in MCI patients. BNM, basal nucleus of Meynert; Ins/CL, insula/claustrum; AVLT, Auditory Verbal Learning Test; FC, functional connectivity; ***indicates p < 0.0001.

Correlation of BNM-FC with Neuropsychological Scores

Pearson’s correlation showed that BNM-FC with the left insula/claustrum was positively associated with the memory performances measured by AVTL-immediate recall (r = 0.41, p < 0.0001) in MCI patients (Figure 2B). On the other hand, no significant correlation was detected between BNM-FC and neuropsychological measures in HCs.

Discussion

The present study examined the BNM-FC in MCI patients in comparison to HCs in a relatively large sample of participants. The findings showed decreased BNM-FC at the left insula/claustrum in MCI patients, as compared to HCs. Furthermore, decreased BNM-insula/claustrum functional connectivity was positively associated with impaired performance as measured by the AVLT- immediate recall in MCI patients.

The insula plays a critical role in cognition, emotion, sensory processing and autonomic control (Naqvi et al., 2007; Allen et al., 2008; Kurth et al., 2010). It is also involved in integrating somatosensory, autonomic and cognitive-affective information to guide behavior (Christopher et al., 2014) and switching brain network activities to support various aspects of cognitive functions (Seeley et al., 2007). Studies in monkeys showed that the density of acetylcholinesterase containing fibers (Mesulam et al., 1984) and choline acetyltransferase activities are particularly rich in the insula (Mesulam et al., 1986). Previous studies revealed that the insula was affected in individuals with MCI (Xie et al., 2012) and at risk of developing AD (Foundas et al., 1997) and insula atrophy effectively discriminated AD patients from the healthy populations (Fan et al., 2008; Insel et al., 2015). The Aβ plaques, neurofibrillary tangles and significant volume atrophy have all been reported in the insula in MCI and AD patients (Karas et al., 2004; Braak et al., 2006; He et al., 2015; Ting et al., 2015; Zhao Z. L. et al., 2015). Furthermore, whole-brain correlational analyses revealed that cognitive performance was associated with the volume (Farrow et al., 2007; Lu et al., 2016; Tillema et al., 2016), functional activity and intrinsic connectivity of the insula in MCI patients (Xie et al., 2012; Nellessen et al., 2015).

The striatum, including claustrum, putamen/pallidum and caudate (Chikama et al., 1997) are of central importance to cognitive motor functions (Christopher et al., 2015). The claustrum is an important albeit less studied part of the striatum. Previous studies reported that the claustrum was activated during episodic memory retrieval in HCs (Schwindt and Black, 2009). Recent work demonstrated that the claustrum receives input from multiple brain regions such as the parietal and the medial temporal structures (Park et al., 2012; Torgerson et al., 2015), while projecting to the insula and frontal pole (Burman et al., 2011). Via this anatomical connectivity, the claustrum may play an important role in binding multiple sources of information to facilitate memory-guided behavior. The claustrum showed neurofibrillary, amyloid pathology (Morys et al., 1996) and reduced choline acetyltransferase (Ohara et al., 1996, 1999; Gill et al., 2007) in both MCI and AD. Wang et al. (2016) reported that disrupted amygdala connectivity with the claustrum in AD patients. Thus, in line with these studies, the present work reveals the existence of altered BNM-FC at the claustrum in MCI patients.

Greater decrease in BNM-FC with insula/claustrum was associated with lower verbal episodic memory scores in MCI patients. The claustrum and the insula are functionally and structurally connected (Chikama et al., 1997). The striatum receives insular projections primarily to support motivated behavior, including reward processing and approach and avoidance learning (Chikama et al., 1997). The perisylvian division of the cholinergic fiber bundles originating from BNM traveled within the claustrum and supplied innervations to the insula (Selden et al., 1998). Previous studies revealed that the insula/claustrum is a crucial hub of the brain network integrating information from multiple brain regions through its extensive reciprocal connections to neocortical, limbic and paralimbic structures (Crick and Koch, 2005; Fernández-Miranda et al., 2008; Park et al., 2012; Torgerson et al., 2015). More recently, Seo and Choo (2016) demonstrated positive correlations between memory performance and regional cerebral glucose metabolism in bilateral claustrum and the left insula in MCI. A single photon emission computed tomography study also reported significant correlation between verbal memory test performance and brain perfusion in the left insula and claustrum in AD patients (Nobili et al., 2007). Thus, the positive correlation between verbal episodic memory scores and the BNM-FC with the left claustrum/insula suggests decline in episodic memory in MCI patients in association with the inefficient information integration and decreased functional connectivity at the insula and claustrum.

Conclusion

In conclusion, MCI patients present significant changes of BNM-FC at the left insula and the claustrum in association with immediate recall during AVLT. These new findings may advance research of the cholinergic bases of cognitive dysfunction during healthy aging and in individuals at risk of developing AD.

Limitations

Several limitations need to be considered for this study. First, those are a cross-sectional study finding and a longitudinal study is needed to understand how BNM-FC may be related to disease progression. Longitudinal follow-up of the patients would allow us to examine whether these neural phenotypes could predict onset of AD in this MCI cohort. Second, the matching of MCI and HCs groups were marginally significant. Although these factors were included as covariates in data analyses, we could not rule out their potential impact on the current results. Finally, human brains are highly varied among different demographics (e.g., gender, age and race). A recent study has demonstrated that the Chinese brain atlas improved accuracy and reduced anatomical variability during registration (Liang et al., 2015). In the current study, the data of participants were normalized to MNI152. Future studies involving Chinese populations should be considered to normalize to Chinese 2020 (a typical statistical Chinese brain template).

Author Contributions

HL and XJ carried out data collection and analysis and wrote the manuscript. ZQ helped with data interpretation. XF, TM and HN carried out data collection. CRL contributed to conceptualization of the study and revision of the manuscript. KL contributed to conceptualization and design of the study and revised the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported partly by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31400958, 81471649, 81571648, 61672065 and 81370037), Clinical Medicine Development Special Funding from the Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospital (ZYLX201609) and Key Projects in the National Science and Technology Pillar Program during the Twelfth Five-year Plan Period (2012BAI10B04).

Footnotes

- ^ http://www.alivelearn.net/xjview

- ^ http://afni.nimh.nih.gov/pub/dist/doc/program_help/3dClustSim.html

References

Albert, M. S., DeKosky, S. T., Dickson, D., Dubois, B., Feldman, H. H., Fox, N. C., et al. (2011). The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the national institute on aging-Alzheimer’s association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 7, 270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008

Allen, J. S., Emmorey, K., Bruss, J., and Damasio, H. (2008). Morphology of the insula in relation to hearing status and sign language experience. J. Neurosci. 28, 11900–11905. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3141-08.2008

Arendt, T., Brückner, M. K., Morawski, M., Jäger, C., and Gertz, H. (2015). Early neurone loss in Alzheimer’s disease: cortical or subcortical? Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 3:10. doi: 10.1186/s40478-015-0187-1

Behzadi, Y., Restom, K., Liau, J., and Liu, T. T. (2007). A component based noise correction method (CompCor) for BOLD and perfusion based fMRI. Neuroimage 37, 90–101. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.04.042

Biswal, B., Yetkin, F. Z., Haughton, V. M., and Hyde, J. S. (1995). Functional connectivity in the motor cortex of resting human brain using echo-planar MRI. Magn. Reson. Med. 34, 537–541. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910340409

Blokland, A., Honig, W., and Raaijmakers, W. G. (1992). Effects of intra-hippocampal scopolamine injections in a repeated spatial acquisition task in the rat. Psychopharmacology 109, 373–376. doi: 10.1007/bf02245886

Boccia, M. M., Acosta, G. B., Blake, M. G., and Baratti, C. M. (2004). Memory consolidation and reconsolidation of an inhibitory avoidance response in mice: effects of i.c.v. injections of hemicholinium-3. Neuroscience 124, 735–741. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.01.001

Boccia, M. M., Blake, M. G., Acosta, G. B., and Baratti, C. M. (2003). Atropine, an anticholinergic drug, impairs memory retrieval of a high consolidated avoidance response in mice. Neurosci. Lett. 345, 97–100. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00493-2

Boccia, M. M., Blake, M. G., Baratti, C. M., and McGaugh, J. L. (2009). Involvement of the basolateral amygdala in muscarinic cholinergic modulation of extinction memory consolidation. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 91, 93–97. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2008.07.012

Braak, H., Alafuzoff, I., Arzberger, T., Kretzschmar, H., and Del Tredici, K. (2006). Staging of Alzheimer disease-associated neurofibrillary pathology using paraffin sections and immunocytochemistry. Acta Neuropathol. 112, 389–404. doi: 10.1007/s00401-006-0127-z

Burman, K. J., Reser, D. H., Richardson, K. E., Gaulke, H., Worthy, K. H., and Rosa, M. G. (2011). Subcortical projections to the frontal pole in the marmoset monkey. Eur. J. Neurosci. 34, 303–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07744.x

Chikama, M., McFarland, N. R., Amaral, D. G., and Haber, S. N. (1997). Insular cortical projections to functional regions of the striatum correlate with cortical cytoarchitectonic organization in the primate. J. Neurosci. 17, 9686–9705.

Christopher, L., Duff-Canning, S., Koshimori, Y., Segura, B., Boileau, I., Chen, R., et al. (2015). Salience network and parahippocampal dopamine dysfunction in memory-impaired Parkinson disease. Ann. Neurol. 77, 269–280. doi: 10.1002/ana.24323

Christopher, L., Koshimori, Y., Lang, A. E., Criaud, M., and Strafella, A. P. (2014). Uncovering the role of the insula in non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. Brain 137, 2143–2154. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu084

Cox, R. W., Chen, G., Glen, D. R., Reynolds, R. C., and Taylor, P. A. (2017). FMRI clustering in AFNI: false positive rates redux. Brain Connect. 7, 152–171. doi: 10.1089/brain.2016.0475

Crick, F. C., and Koch, C. (2005). What is the function of the claustrum? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 360, 1271–1279. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2005.1661

Cullen, K. M., Halliday, G. M., Double, K. L., Brooks, W. S., Creasey, H., and Broe, G. A. (1997). Cell loss in the nucleus basalis is related to regional cortical atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience 78, 641–652. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00569-6

de Lacalle, S., Iraizoz, I., and Ma Gonzalo, L. (1991). Differential changes in cell size and number in topographic subdivisions of human basal nucleus in normal aging. Neuroscience 43, 445–456. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90307-a

Fair, D. A., Schlaggar, B. L., Cohen, A. L., Miezin, F. M., Dosenbach, N. U., Wenger, K. K., et al. (2007). A method for using blocked and event-related fMRI data to study “resting state” functional connectivity. Neuroimage 35, 396–405. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.11.051

Fan, Y., Resnick, S. M., Wu, X., and Davatzikos, C. (2008). Structural and functional biomarkers of prodromal Alzheimer’s disease: a high-dimensional pattern classification study. Neuroimage 41, 277–285. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.02.043

Farrow, T. F. D., Thiyagesh, S. N., Wilkinson, I. D., Parks, R. W., Ingram, L., and Woodruff, P. W. R. (2007). Fronto-temporal-lobe atrophy in early-stage Alzheimer’s disease identified using an improved detection methodology. Psychiatry Res. 155, 11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2006.12.013

Fernández-Miranda, J. C., Rhoton, A. J. Jr., Kakizawa, Y., Choi, C., and Alvarez-Linera, J. (2008). The claustrum and its projection system in the human brain: a microsurgical and tractographic anatomical study. J. Neurosurg. 108, 764–774. doi: 10.3171/JNS/2008/108/4/0764

Ferreira-Vieira, T. H., Guimaraes, I. M., Silva, F. R., and Ribeiro, F. M. (2016). Alzheimer’s disease: targeting the cholinergic system. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 14, 101–115. doi: 10.2174/1570159x13666150716165726

Folstein, M. F., Folstein, S. E., and McHugh, P. R. (1975). “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 12, 189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6

Foundas, A. L., Leonard, C. M., Mahoney, S. M., Agee, O. F., and Heilman, K. M. (1997). Atrophy of the hippocampus, parietal cortex, and insula in Alzheimer’s disease: a volumetric magnetic resonance imaging study. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol. Behav. Neurol. 10, 81–89.

Fox, M. D., and Raichle, M. E. (2007). Spontaneous fluctuations in brain activity observed with functional magnetic resonance imaging. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 8, 700–711. doi: 10.1038/nrn2201

Gauthier, S., Reisberg, B., Zaudig, M., Petersen, R. C., Ritchie, K., Broich, K., et al. (2006). Mild cognitive impairment. Lancet 367, 1262–1270. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68542-5

George, S., Mufson, E. J., Leurgans, S., Shah, R. C., Ferrari, C., and deToledo-Morrell, L. (2011). MRI-based volumetric measurement of the substantia innominata in amnestic MCI and mild AD. Neurobiol. Aging 32, 1756–1764. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.11.006

Gill, S. K., Ishak, M., Dobransky, T., Haroutunian, V., Davis, K. L., and Rylett, R. J. (2007). 82-kDa choline acetyltransferase is in nuclei of cholinergic neurons in human CNS and altered in aging and Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol. Aging 28, 1028–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.05.011

Gratwicke, J., Kahan, J., Zrinzo, L., Hariz, M., Limousin, P., Foltynie, T., et al. (2013). The nucleus basalis of Meynert: a new target for deep brain stimulation in dementia? Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 37, 2676–2688. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.09.003

Greicius, M. D., Srivastava, G., Reiss, A. L., and Menon, V. (2004). Default-mode network activity distinguishes Alzheimer’s disease from healthy aging: evidence from functional MRI. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 101, 4637–4642. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308627101

Grothe, M., Heinsen, H., and Teipel, S. J. (2012). Atrophy of the cholinergic basal forebrain over the adult age range and in early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Biol. Psychiatry 71, 805–813. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.06.019

Grothe, M., Heinsen, H., and Teipel, S. (2013). Longitudinal measures of cholinergic forebrain atrophy in the transition from healthy aging to Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 34, 1210–1220. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.10.018

Grothe, M. J., Schuster, C., Bauer, F., Heinsen, H., Prudlo, J., and Teipel, S. J. (2014). Atrophy of the cholinergic basal forebrain in dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer’s disease dementia. J. Neurol. 261, 1939–1948. doi: 10.1007/s00415-014-7439-z

Grothe, M., Zaborszky, L., Atienza, M., Gil-Neciga, E., Rodriguez-Romero, R., Teipel, S. J., et al. (2010). Reduction of basal forebrain cholinergic system parallels cognitive impairment in patients at high risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. Cereb. Cortex 20, 1685–1695. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp232

Hanyu, H., Asano, T., Sakurai, H., Tanaka, Y., Takasaki, M., and Abe, K. (2002). MR analysis of the substantia innominata in normal aging, Alzheimer disease, and other types of dementia. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 23, 27–32.

He, W., Liu, D., Radua, J., Li, G., Han, B., and Sun, Z. (2015). Meta-analytic comparison between PIB-PET and FDG-PET results in Alzheimer’s disease and MCI. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 71, 17–26. doi: 10.1007/s12013-014-0138-7

Insel, P. S., Mattsson, N., Donohue, M. C., Mackin, R. S., Aisen, P. S., Jack, C. J., et al. (2015). The transitional association between β-amyloid pathology and regional brain atrophy. Alzheimers Dement. 11, 1171–1179. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.11.002

Kann, S., Zhang, S., Manza, P., Leung, H. C., and Li, C. R. (2016). Hemispheric lateralization of resting-state functional connectivity of the anterior insula: association with age, gender, and a novelty-seeking trait. Brain Connect. 6, 724–734. doi: 10.1089/brain.2016.0443

Karas, G. B., Scheltens, P., Rombouts, S. A. R. B., Visser, P. J., van Schijndel, R. A., Fox, N. C., et al. (2004). Global and local gray matter loss in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage 23, 708–716. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.006

Kawas, C. H. (2003). Clinical practice. Early Alzheimer’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 349, 1056–1063. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp022295

Kilimann, I., Grothe, M., Heinsen, H., Alho, E. J., Grinberg, L., Amaro, E. J., et al. (2014). Subregional basal forebrain atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease: a multicenter study. J. Alzheimers Dis. 40, 687–700. doi: 10.3233/JAD-132345

Kurth, F., Zilles, K., Fox, P. T., Laird, A. R., and Eickhoff, S. B. (2010). A link between the systems: functional differentiation and integration within the human insula revealed by meta-analysis. Brain Struct. Funct. 214, 519–534. doi: 10.1007/s00429-010-0255-z

Li, C. R., Ide, J. S., Zhang, S., Hu, S., Chao, H. H., and Zaborszky, L. (2014). Resting state functional connectivity of the basal nucleus of Meynert in humans: in comparison to the ventral striatum and the effects of age. Neuroimage 97, 321–332. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.04.019

Liang, P., Shi, L., Chen, N., Luo, Y., Wang, X., Liu, K., et al. (2015). Construction of brain atlases based on a multi-center MRI dataset of 2020 Chinese adults. Sci. Rep. 5:18216. doi: 10.1038/srep18216

Liang, P., Wang, Z., Yang, Y., Jia, X., and Li, K. (2011). Functional disconnection and compensation in mild cognitive impairment: evidence from DLPFC connectivity using resting-state fMRI. PLoS One 6:e22153. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022153

Liang, P., Wang, Z., Yang, Y., and Li, K. (2012). Three subsystems of the lateral parietal cortex are differently affected in amnesia mild cognitive impairment. J. Alzheimers Dis. 30, 475–487. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-111721

Liu, A. K., Chang, R. C., Pearce, R. K., and Gentleman, S. M. (2015). Nucleus basalis of Meynert revisited: anatomy, history and differential involvement in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 129, 527–540. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1392-5

Lowe, M. J., Mock, B. J., and Sorenson, J. A. (1998). Functional connectivity in single and multisliceechoplanar imaging using resting-state fluctuations. Neuroimage 7, 119–132. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1997.0315

Lu, Y. T., Chang, W. N., Chang, C. C., Lu, C. H., Chen, N. C., Huang, C. W., et al. (2016). Insula volume and salience network are associated with memory decline in parkinson disease: complementary analyses of voxel-based morphometry versus volume of interest. Parkinsons Dis. 2016:2939528. doi: 10.1155/2016/2939528

Manza, P., Zhang, S., Hu, S., Chao, H. H., Leung, H. C., and Li, C. R. (2015). The effects of age on resting state functional connectivity of the basal ganglia from young to middle adulthood. Neuroimage 107, 311–322. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.12.016

Mesulam, M. M., Mufson, E. J., Levey, A. I., and Wainer, B. H. (1983). Cholinergic innervation of cortex by the basal forebrain: cytochemistry and cortical connections of the septal area, diagonal band nuclei, nucleus basalis (substantia innominata) and hypothalamus in the rhesus monkey. J. Comp. Neurol. 214, 170–197. doi: 10.1002/cne.902140206

Mesulam, M. M., Rosen, A. D., and Mufson, E. J. (1984). Regional variations in cortical cholinergic innervation: chemoarchitectonics of acetylcholinesterase-containing fibers in the macaque brain. Brain Res. 311, 245–258. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90087-8

Mesulam, M. M., Volicer, L., Marquis, J. K., Mufson, E. J., and Green, R. C. (1986). Systematic regional differences in the cholinergic innervation of the primate cerebral cortex: distribution of enzyme activities and some behavioral implications. Ann. Neurol. 19, 144–151. doi: 10.1002/ana.410190206

Mitchell, A. J. (2009). A meta-analysis of the accuracy of the mini-mental state examination in the detection of dementia and mild cognitive impairment. J. Psychiatr. Res. 43, 411–431. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.04.014

Morris, J. C. (1993). The clinical dementia rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology 43:2412. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a

Morys, J., Bobinski, M., Wegiel, J., Wisniewski, H. M., and Narkiewicz, O. (1996). Alzheimer’s disease severely affects areas of the claustrum connected with the entorhinal cortex. J. Hirnforsch. 37, 173–180.

Naqvi, N. H., Rudrauf, D., Damasio, H., and Bechara, A. (2007). Damage to the insula disrupts addiction to cigarette smoking. Science 315, 531–534. doi: 10.1126/science.1135926

Nasreddine, Z. S., Phillips, N. A., Bédirian, V., Charbonneau, S., Whitehead, V., Collin, I., et al. (2005). The montreal cognitive assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 53, 695–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x

Nellessen, N., Rottschy, C., Eickhoff, S. B., Ketteler, S. T., Kuhn, H., Shah, N. J., et al. (2015). Specific and disease stage-dependent episodic memory-related brain activation patterns in Alzheimer’s disease: a coordinate-based meta-analysis. Brain Struct. Funct. 220, 1555–1571. doi: 10.1007/s00429-014-0744-6

Nilsson, F. M. (2007). Mini mental state examination (MMSE)—probably one of the most cited papers in health science. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 116, 156–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01037.x

Nobili, F., Koulibaly, P. M., Rodriguez, G., Benoit, M., Girtler, N., Robert, P. H., et al. (2007). 99mTc-HMPAO and 99mTc-ECD brain uptake correlates of verbal memory in Alzheimer’s disease. Q. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 51, 357–363.

Nordberg, A. (1993). In vivo detection of neurotransmitter changes in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci. 695, 27–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb23022.x

Ohara, K., Miyoshi, K., Takauchi, S., Kokai, M., Nakajima, T., and Morita, Y. (1999). A morphometric study of subcortical changes in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropathology 19, 161–171. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1789.1999.00214.x

Ohara, K., Takauchi, S., Miyoshi, K., Kokai, M., and Morita, Y. (1996). A morphometric study of subcortical neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropathology 16, 231–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1789.1996.tb00187.x

Park, S., Tyszka, J. M., and Allman, J. M. (2012). The claustrum and insula in microcebusmurinus: a high resolution diffusion imaging study. Front. Neuroanat. 6:21. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2012.00021

Petersen, R. C. (2011). Clinical practice. Mild cognitive impairment. N. Engl. J. Med. 364, 2227–2234. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0910237

Petersen, R. C., Stevens, J. C., Ganguli, M., Tangalos, E. G., Cummings, J. L., and DeKosky, S. T. (2001). Practice parameter: early detection of dementia: mild cognitive impairment (an evidence-based review). Report of the quality standards subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 56, 1133–1142. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.9.1133

Power, J. D., Barnes, K. A., Snyder, A. Z., Schlaggar, B. L., and Petersen, S. E. (2012). Spurious but systematic correlations in functional connectivity MRI networks arise from subject motion. Neuroimage 59, 2142–2154. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.10.018

Power, J. D., Schlaggar, B. L., and Petersen, S. E. (2015). Recent progress and outstanding issues in motion correction in resting state fMRI. Neuroimage 105, 536–551. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.10.044

Power, A. E., Vazdarjanova, A., and McGaugh, J. L. (2003). Muscarinic cholinergic influences in memory consolidation. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 80, 178–193. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7427(03)00086-8

Qi, Z., Wu, X., Wang, Z., Zhang, N., Dong, H., Yao, L., et al. (2010). Impairment and compensation coexist in amnestic MCI default mode network. Neuroimage 50, 48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.12.025

Ruberg, M., Mayo, W., Brice, A., Duyckaerts, C., Hauw, J. J., Simon, H., et al. (1990). Choline acetyltransferase activity and [3H]vesamicol binding in the temporal cortex of patients with Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease and rats with basal forebrain lesions. Neuroscience 35, 327–333. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90086-j

Saad, Z. S., Reynolds, R. C., Jo, H. J., Gotts, S. J., Chen, G., Martin, A., et al. (2013). Correcting brain-wide correlation differences in resting-state fMRI. Brain Connect. 3, 339–352. doi: 10.1089/brain.2013.0156

Schwindt, G. C., and Black, S. E. (2009). Functional imaging studies of episodic memory in Alzheimer’s disease: a quantitative meta-analysis. Neuroimage 45, 181–190. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.11.024

Seeley, W. W., Menon, V., Schatzberg, A. F., Keller, J., Glover, G. H., Kenna, H., et al. (2007). Dissociable intrinsic connectivity networks for salience processing and executive control. J. Neurosci. 27, 2349–2356. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5587-06.2007

Selden, N. R., Gitelman, D. R., Salamon-Murayama, N., Parrish, T. B., and Mesulam, M. M. (1998). Trajectories of cholinergic pathways within the cerebral hemispheres of the human brain. Brain 121, 2249–2257. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.12.2249

Seo, E. H., Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, and Choo, I. L. H. (2016). Amyloid-independent functional neural correlates of episodic memory in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 43, 1088–1095. doi: 10.1007/s00259-015-3261-9

Sorg, C., Riedl, V., Mühlau, M., Calhoun, V. D., Eichele, T., Läer, L., et al. (2007). Selective changes of resting-state networks in individuals at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 104, 18760–18765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708803104

Tillema, J. M., Hulst, H. E., Rocca, M. A., Vrenken, H., Steenwijk, M. D., Damjanovic, D., et al. (2016). Regional cortical thinning in multiple sclerosis and its relation with cognitive impairment: a multicenter study. Mult. Scler. 22, 901–909. doi: 10.1177/1352458515607650

Ting, W. K., Fischer, C. E., Millikin, C. P., Ismail, Z., Chow, T. W., and Schweizer, T. A. (2015). Grey matter atrophy in mild cognitive impairment/early Alzheimer disease associated with delusions: a voxel-based morphometry study. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 12, 165–172. doi: 10.2174/1567205012666150204130456

Torgerson, C. M., Irimia, A., Goh, S. Y., and Van Horn, J. D. (2015). The DTI connectivity of the human claustrum. Hum. Brain Mapp. 36, 827–838. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22667

Vogels, O. J. M., Broere, C. A., Ter Laak, H. J., Ten Donkelaar, H. J., Nieuwenhuys, R., and Schulte, B. P. M. (1990). Cell loss and shrinkage in the nucleus basalis Meynert complex in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 11, 3–13. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(90)90056-6

Volkmar, F. R. (2013). “Auditory verbal learning test,” Encyclopedia of Autism Spectrum Disorders, (New York, NY: Springer), 328. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-1698-3

Wang, L., Zang, Y., He, Y., Liang, M., Zhang, X., Tian, L., et al. (2006). Changes in hippocampal connectivity in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease: evidence from resting state fMRI. Neuroimage 31, 496–504. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.12.033

Wang, Z., Zhang, M., Han, Y., Song, H., Guo, R., and Li, K. (2016). Differentially disrupted functional connectivity of the subregions of the amygdala in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Xray Sci. Technol. 24, 329–342. doi: 10.3233/XST-160556

Whitehouse, P. J., Price, D. L., Clark, A. W., Coyle, J. T., and DeLong, M. R. (1981). Alzheimer disease: evidence for selective loss of cholinergic neurons in the nucleus basalis. Ann. Neurol. 10, 122–126. doi: 10.1002/ana.410100203

Whitfield-Gabrieli, S., and Nieto-Castanon, A. (2012). Conn: a functional connectivity toolbox for correlated and anticorrelated brain networks. Brain Connect. 2, 125–141. doi: 10.1089/brain.2012.0073

Winters, B. D., and Bussey, T. J. (2005). Removal of cholinergic input to perirhinal cortex disrupts object recognition but not spatial working memory in the rat. Eur. J. Neurosci. 21, 2263–2270. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04055.x

Xie, C., Bai, F., Yu, H., Shi, Y., Yuan, Y., Chen, G., et al. (2012). Abnormal insula functional network is associated with episodic memory decline in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Neuroimage 63, 320–327. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.06.062

Zaborszky, L., Hoemke, L., Mohlberg, H., Schleicher, A., Amunts, K., and Zilles, K. (2008). Stereotaxic probabilistic maps of the magnocellular cell groups in human basal forebrain. Neuroimage 42, 1127–1141. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.05.055

Zhang, S., Hu, S., Chao, H. H., and Li, C. R. (2016). Resting-state functional connectivity of the locus coeruleus in humans: in comparison with the ventral tegmental area/substantia nigra pars compacta and the effects of age. Cereb. Cortex 26, 3413–3427. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhv172

Zhao, Z. L., Fan, F. M., Lu, J., Li, H. J., Jia, L. F., Han, Y., et al. (2015). Changes of gray matter volume and amplitude of low-frequency oscillations in amnestic MCI: an integrative multi-modal MRI study. Acta Radiol. 56, 614–621. doi: 10.1177/0284185114533329

Keywords: basal nucleus of Meynert, basal forebrain, cholinergic bases, mild cognitive impairment, functional connectivity

Citation: Li H, Jia X, Qi Z, Fan X, Ma T, Ni H, Li CR and Li K (2017) Altered Functional Connectivity of the Basal Nucleus of Meynert in Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Resting-State fMRI Study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 9:127. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2017.00127

Received: 20 November 2016; Accepted: 18 April 2017;

Published: 04 May 2017.

Edited by:

Christos Frantzidis, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, GreeceReviewed by:

Stephen J. Gotts, National Institute of Mental Health (NIH), USAVeena A. Nair, University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA

Copyright © 2017 Li, Jia, Qi, Fan, Ma, Ni, Li and Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kuncheng Li, cjr.likuncheng@vip.163.com

† These authors have contributed equally to this work.

Hui Li

Hui Li Xiuqin Jia

Xiuqin Jia Zhigang Qi

Zhigang Qi Xiang Fan

Xiang Fan Tian Ma

Tian Ma Hong Ni

Hong Ni Chiang-shan R. Li

Chiang-shan R. Li Kuncheng Li

Kuncheng Li