How a cerebral hemorrhage altered my art

- Art Practice and Disability Studies, University of California Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, USA

“How a Cerebral Hemorrhage Altered My Art” examines how a massive stroke affected my art practice. The paralysis that ensued forced me to switch hands and become a left-handed painter. It was postulated by several neuroscientists that the “interpreter” in my brain was severely damaged during my CVA. This has had a profoundly liberating effect on my work. Whereas my pre-stroke period had the tendency to be over-intellectualized and forced, my post-stroke art is less self-conscious, more urgent and expressive. The primary subject matter of both periods is the brain. In my practice as an artist, my stroke is a challenge and an opportunity rather than a loss.

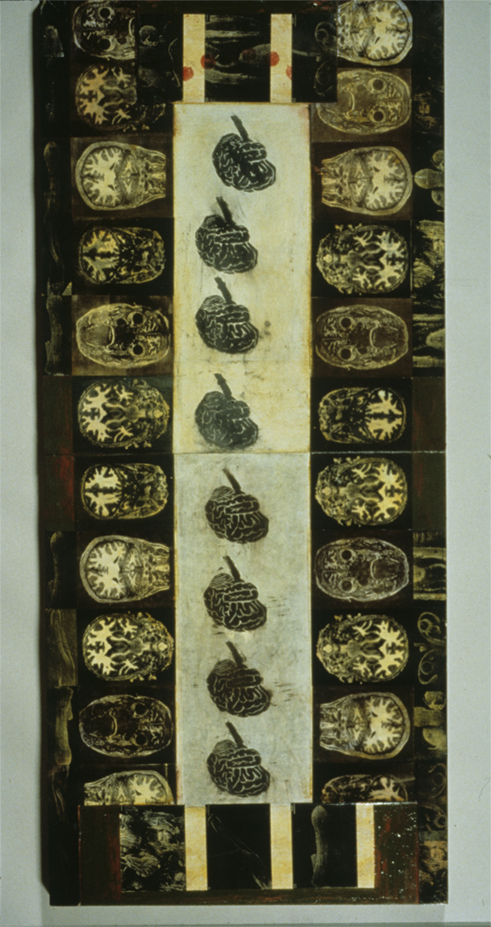

Out of the blue, in 1997, I had a massive stroke at age 44. Brains had been on my mind for years before that. At the beginning of the 1990s I had started to incorporate brain imagery into my paintings. I was fascinated by the theories of the holographic paradigm promoted by Michael Talbot in The Universe as a Hologram. This new way of perceiving reality made perfect sense to me although it was labeled a “fringe science.” I did several paintings using MRI’s I found deep in the biosciences library at UC Berkeley. Small abstract holograms were embedded in the surface of the paintings, such as Fun Puddle (Figure 1). These paintings failed at expressing thoughts about the holographic paradigm but were visually successful and led me on my way.

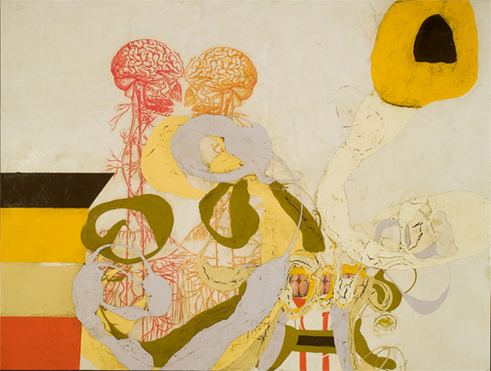

I continued to use brain representations through the mid 1990s but my interest was shared with telescopic imagery. Similar to the microscopic views of the body, they were both realities that one could not perceive with the naked eye. I was obsessed with CIA satellite imagery especially photos taken in Russia of nuclear test sites as in the painting Aldrich Ames (Figure 2). My interest in these images coincided with my sense that I was a spy going through the tenure process in my work as a professor of art practice. In June of 1996, I achieved tenure and set out to have a relaxing post-tenure year.

The next May I experienced a cerebral hemorrhage affecting the parietal lobe of the dominant hemisphere. I lost my ability to walk, talk, read, and think as my right side became paralyzed within the course of 2 min. It happened during a graduate student’s critique. Within those minutes my life was completely changed. I do not recall saying this but one of my colleagues reported that the last thing I said was “Oh no, not again.” I was referring to the death of my father at age 33 from an aneurysm.

This was when my life caught up to my art.

In rehab I was repeatedly asked if I wanted to paint as art therapy. I haughtily answered no, that I would just wait until I got the use of my right hand back again. Thankfully, I did not hold onto this attitude for long because my right hand never has regained function. I would not have become a more fluid and urgent left-handed painter. It turns out that my left hand was, in my case, the better painting hand, and that painting in my studio was the most effective occupational therapy there could have been for me.

Six months later after my brain had absorbed my spilled blood I had a cerebral angiogram. Relieved that it was over and the possible second stroke had not occurred, I sat up on the gurney and looked at the computer screen in the corner of the room. The images of the arterial system of my brain both stunned and reminded me of the Southern Song Dynasty Chinese landscape paintings that I had deeply admired. I immediately said without thinking, “I need those images.” The room broke out in laughter which I still do not understand. I repeated, “No, I am an artist and I really need those images.” A few minutes later the radiologist entered the room and handed me the full set. He simultaneously told me I would not need brain surgery. I was immensely thankful that I did not have to wait 2 weeks to hear the desired results and grateful to my doctor for taking my request seriously. I knew in an instant that I would use those images in my paintings and clearly saw a blueprint of my artistic future within them. In them was an assurance that I would have a painter’s life again.

I returned to my studio with a newfound vigor. Of course I had to make adjustments. Using my left hand was rather like an athletic challenge and it helped me to discover that I was slightly ambidextrous. I was aware of how lucky I was to be a painter and able to continue my vocation by merely changing hands. For example, it was fortuitous that I was not a sculptor, a musician, a dentist, or a brain surgeon.

I compensated for my lesser amount of fine motor skills in my left hand by working on much larger canvases. This allowed for larger brushes and an escape from meticulous detail. I tried to detoxify my process as much as possible as a preventive measure by abandoning using solely oil paints and their hazardous mediums. I switched to a mixed-media method where I combined acrylic and latex paint using oil at the very end of my process. I began to work on a horizontal surface instead of on the wall because of the weight of the canvases, my inability to move them, and to keep them from dripping. I converted my handmade platform bed that I could not get up on any longer into my painting table. I used a rolling chair to go around and around those large surfaces often working on one painting for a year unlike my pre-stroke pace. This was because of the greater size of the canvases as well as my newfound interest in building up the grounds of the painting before I began to apply paint. It takes longer to do anything now, which even in our speeded up world is not necessarily a bad thing.

I soon became proficient at visualizing what a painting would look like once it was hung vertically. Because I found mixing paint with one hand too difficult I soon began to rely on pre-mixed paint. Hence my palette changed and I ventured into using “ugly colors” with sweet pastel ones. Most importantly there was a new ease in my process. I did not feel I had to intellectualize away my every move and an extreme amount of struggle faded away. A freer, more enjoyable state of painting existed far different than in my previous work. I was also more detached from them often feeling that they went through me which at the end left me wondering did I make these paintings?

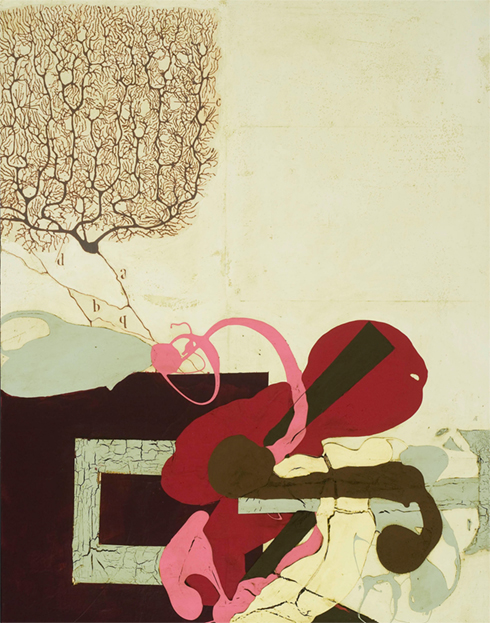

The paintings and prints done in the post-stroke period have combined brain images with the visual interpretations of the medieval manuscript, The Lemegeton. I had begun using the sigils in my art in 1992 but I did so because I admired their esthetic attributes, their unsymmetrical stance, and their immaculate calligraphic quality rather than a belief in their efficacy. This text contains seals attributed to King Solomon, the wise leader found in the Bible, Talmud, and Koran. His wealth and fame were said to be the result of magic. These seals allegedly represent the spirits he harnessed to achieve his wisdom, fame, wealth, and spiritual power. These spirits were used to answer questions and provide assistance. They were conduits for desire. The signets used in my post-stroke art purport to aid the supplicant in matters of healing. I began to reassess their effectiveness.

Facility of Speech (Figure 3) is a prime example of my use of the seals. It was made when I was anxious about returning to teaching. For almost 2 years, thanks to UC Berkeley, I had worked diligently on rehabilitation but usually in a one-to-one situation. The rest of my time was spent alone in my studio. The thought of leading an entire class was terrifying. I was still very labile. I was afraid that students would not understand it when I broke down crying and through my tears pleaded that I was in fact exceedingly happy. So I used the seal Bune which gives you facility of speech and a way with words. In the painting it is in the light green paint scrawled over my brains in loopy yet graceful lines. Facility of Speech was exhibited in the 2000 Whitney Museum Biennial.

One of the classes I taught at Berkeley was about the history of materials and techniques of painting. I took it very seriously before my stroke believing I was there so that students would learn the chemistry of painting such as how to avoid cracks. I would think to myself when I detected cracks, “he obviously does not know how to paint.” After the stroke, I slowly accrued paint on my canvas, going over the contours of the seal again and again. The light colors of my paintings, when built up, began to crack. This time I felt differently toward cracks and made them more pronounced by filling them with a darker oil paint. There was a bonus in being comfortable with their conceptual meaning. The cracks soon became pre-planned as a compositional device and as a metaphorical placeholder.

The final post-stroke element of my work is something one can not see or perceive. It is a spiritual device that I employ as my own form of ancestor worship and as the focus of intention for the painting. Before I assign each painting a seal, I choose a close person that has passed both to be in charge of the efficacy of the seal and to whom it is dedicated. This is my method for effective grieving, something I have had to do a lot of in my life.

Most of the press I have gotten since my CVA is based in the popular media versus art journals. I make an excellent “overcoming narrative” as it is known in the field of Disability Studies. It refers to the media’s dealing with disability only when a disabled person beats all the obstacles so as to appear as “normal.” Other articles, especially Peter Waldman’s of the Wall Street Journal, proposed that my new success came from changes in my brain, particularly in the disruption of “the interpreter.” My artist friends vehemently disagreed with this assessment, preferring to believe it had something to do with the 20-years of painting I had done before my cerebral hemorrhage and my ample time to paint while I was recovering. I leave it up to mystery, a category that drives my doctors crazy.

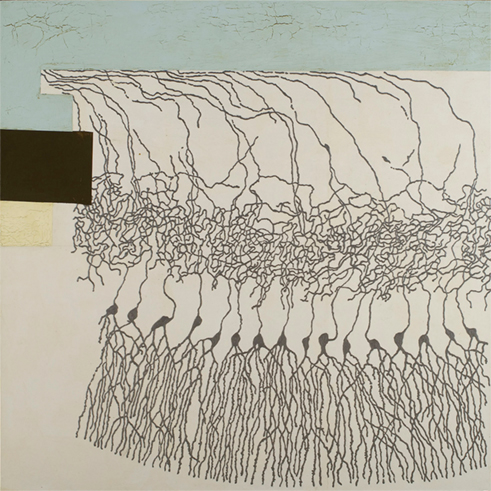

The paintings garnered a Guggenheim fellowship in 2005–2006. I proposed incorporating brain imagery of western neuroanatomy from the sixteenth century to the twenty-first century. I became fascinated by the traditional role of the artist to pictorially represent what the anatomist discovers. In today’s medical imaging technology, the role of the artist is eliminated. The digital process ostensibly avoids intervention, the human hand, and the craftsmanship of printmakers. What happens when the artist comes at the end of this process instead of in the middle, when the emphasis is on interpretation rather than observation or imitation?

In this body of work I shifted my attention to the nervous system. An example is the painting Pump, Drug, Computer (Figure 4). Enlarged digital copies on rice paper of Vesalius’ nervous system are tiled onto the canvas looking at each other. The seal Foras is employed which supposedly makes one happy, wealthy, and wise. It also represents my two fathers. The title of the painting refers to the fact that I had just had a baclofen pump that has a computer within it implanted within my stomach. I laughed with my digital media colleagues that they may be the most adept at using a computer but I am the only one among us that has a computer inside of me. In Vesalius’s Pump (Figure 5) I combine images of his brains with my carotid artery while evoking the seal Sallos which brings love to all that ask.

The power and the helpfulness of limitations are often overlooked in life. Limitations spur you on as they challenge you and provide for creative inventions. As an artist they help you define yourself and focus on what does work. Many famous artists have had disabilities that have not restricted them artistically such as Michelangelo’s Asperger’s syndrome; Goya’s deafness; Degas, Monet, and Matisse’s visual impairments; Toulouse Lautrec’s dwarfism; and Frida Kahlo’s spina bifida, polio, and trolley accident. We also do not need anyone’s pity for our conditions or to be solely defined by our medical condition. I firmly know my life has been considerably enhanced and made richer after acquiring my disability.

Santiago Ramon y Cajal’s limitation was that he really wanted to become an artist but his anatomist father prevented that profession preferring his son to follow his medical footsteps. In the painting Cajal’s Revenge (Figure 6), a blown-up version of Cajal’s famous rendition of the Purkinje cell is placed above a painted seal. Being one of several nineteenth to twentieth century anatomists who drew his own illustrations, Cajal won the Nobel Prize in 1906 with Camillo Golgi. Cajal drew his own stained neurons using Golgi’s techniques that were improved upon by Cajal. I have used his illustrations in many paintings of this series concluding with a 72″ × 72″ work entitled One in a Hundred Billion (Figure 7) where a single neuron is painted in silver paint and fills the large, square canvas.

This body of work was shown at the National Academy of Science in Washington D.C. in 2007 and in Gallery Paule Anglim in San Francisco in late 2008. After my exhibit in 2008 I experienced an artist’s block knowing internally it was time to change directions. This was painful because before I had always had my art to turn to in order to face life’s difficulties. When this became absent, I felt bereft. After nine long months, I had a vision upon waking up one morning of a diptych with a long skirt attached. Who knows where that came from but I figured this could be a way out. I started to construct figures made up of the brains I had been using in my previous work and began making long skirts for each of them. I substituted the brains for eyeballs, faces, and breasts. For example, in Neuron Nurse (Figure 8) I painted Ramon Y Cajal’s neurons to form the face, arms, and chest. In Mansur’s Healer (Figure 9) I used four fMRI’s from the Helen Wills Institute of Neuroscience at UC Berkeley where I am the artist-in-residence to create the head and an illustration from The Tashrih Mansuri (Anatomy of Mansur) to form the body. This series will include 10 paintings that will be shown in spring 2012 and is known as the Healers of the Yelling Clinic.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Keywords: paintings, brain, CVA, neuro-anatomical illustrations, artist, cerebral angiogram

Citation: Sherwood K (2012) How a cerebral hemorrhage altered my art. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 6:55. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00055

Received: 13 April 2011; Accepted: 29 February 2012;

Published online: 03 April 2012.

Edited by:

Idan Segev, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, IsraelReviewed by:

Idan Segev, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, IsraelVered Aviv, The Jerusalem Academy of Music and Dance, Israel

Copyright: © 2012 Sherwood. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial License, which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in other forums, provided the original authors and source are credited.

*Correspondence: Katherine Sherwood, Art Practice and Disability Studies, University of California Berkeley, 345 Kroeber Hall, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA. e-mail: sherwood@berkeley.edu