Toward a Quantum Theory of Humor

- 1Department of Psychology, University of British Columbia, Kelowna, BC, Canada

- 2Department of Mathematical Sciences, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

This paper proposes that cognitive humor can be modeled using the mathematical framework of quantum theory. We begin with brief overviews of both research on humor, and the generalized quantum framework. We show how the bisociation of incongruous frames or word meanings in jokes can be modeled as a linear superposition of a set of basis states, or possible interpretations, in a complex Hilbert space. The choice of possible interpretations depends on the context provided by the set-up vs. the punchline of a joke. We apply the approach to a verbal pun, and consider how it might be extended to frame blending. An initial study of that made use of the Law of Total Probability, involving 85 participant responses to 35 jokes (as well as variants), suggests that the Quantum Theory of Humor (QTH) proposed here provides a viable new approach to modeling humor.

1. Introduction

Humor has been called the “killer app” of language [1]; it showcases the speed, playfulness, and flexibility of human cognition, and can instantaneously put people in a positive mood. For over a 100 years scholars have attempted to make sense of the seemingly nonsensical cognitive processes that underlie humor. Despite considerable progress with respect to categorizing different forms of humor (e.g., irony, jokes, cartoons, and slapstick) and understanding what people find funny, there has been little investigation of the question: What kind of formal theory do we need to model the cognitive representation of a joke as it is being understood?

This paper attempts to answer this question with a new model of humor that uses a generalization of the quantum formalism. The last two decades have witnessed an explosion of applications of quantum models to psychological phenomena that feature ambiguity and/or contextuality [2–4]. Many psychological phenomena have been studied using quantum models, including the combination of words and concepts [5–10], similarity and memory [11, 12], information retrieval [13, 14], decision making and probability judgment errors [15–19], vision [20, 21], sensation–perception [22], social science [23, 24], cultural evolution [25, 26], and creativity [27, 28]. These quantum inspired approaches make no assumption that phenomena at the quantum level affect the brain, but rather, draw solely on abstract formal structures that, as it happens, found their first application in quantum mechanics. They utilize the structurally different nature of quantum probability. While in classical probability theory events are drawn from a common sample space, quantum models define states and variables with reference to a context, represented using a basis in a Hilbert space. This results in phenomena such as interference, superposition and entanglement, and ambiguity with respect to the outcome is resolved with a quantum measurement and a collapse to a definite state.

This makes the quantum inspired approach an interesting new candidate for a theory of humor. Humor often involves ambiguity due to the presence of incongruous schemas: internally coherent but mutually incompatible ways of interpreting or understanding a statement or situation. As a simple example, consider the following pun:

“Time flies like an arrow. Fruit flies like a banana.”

This joke hangs on the ambiguity of the phrase FRUIT FLIES, where the word FLIES can be either a verb or a noun. As a verb, FLIES means “to travel through the air.” However, as a noun, FRUIT FLIES are “insects that eat fruit.” Quantum formalisms are highly useful for describing cognitive states that entail this form of ambiguity. This paper will propose that the quantum approach enables us to naturally represent the process of “getting a joke.”

We start by providing a brief overview of the relevant research on humor.

2. Brief Background in Humor Research

Even within psychology, humor is approached from multiple directions. Social psychologists investigate the role of humor in establishing, maintaining, and disrupting social cohesion and social status, developmental psychologists investigate how the ability to understand and generate humor changes over a lifetime, and health psychologists investigate possible therapeutic aspects of humor. This paper deals solely with the cognitive aspect of humor. Much cognitive theorizing about humor assumes that it is driven by the simultaneous perception [29, 30] or “bisociation” [31] of incongruent schemas. Schemas can be either static frames, as in a cartoon, or dynamically unfolding scripts, as in a pun. For example, in the “time flies” joke above, interpreting the phrase FRUIT FLIES as referring to the insect is incompatible with interpreting it as food traveling through the air. Incongruity is generally accompanied by the violation of expectations and feelings of surprise. While earlier approaches posited that humor comprehension involves the resolution of incongruous frames or scripts [32, 33], the notion of resolution often plays a minor role in contemporary theories, which tend to view the punchline as activating multiple schemas simultaneously and thereby underscoring ambiguity (e.g., 34, 35).

There are computational models of humor detection and understanding (e.g., 36), in which the interpretation of an ambiguous word or phrase changes as new surrounding contextual information is parsed. For example, in the “time flies” joke, this kind of model would shift from interpreting FLIES as a verb to interpreting it as a noun. There are also computational models of humor that generate jokes through lexical replacement; for example, by replacing a “taboo” word with a similar-sounding innocent word (e.g., [37, 38]). These computational approaches to humor are interesting, and occasionally generate jokes that are laugh-worthy. However, while they tell us something about humor, we claim that they do not provide an accurate model of the cognitive state of a human mind at the instant of perceiving a joke. As mentioned above, humor psychologists believe that humor often involves not just shifting from one interpretation of an ambiguous stimulus to another, but simultaneously holding in mind the interpretation that was perceived to be relevant during the set-up and the interpretation that is perceived to be relevant during the punchline. For this reason, we turned to the generalized quantum formalism as a possible approach for modeling the cognitive state of holding two schemas in mind simultaneously.

3. Brief Background in Generalized Quantum Modeling

Classical probability describes events by considering subsets of a common sample space [39]. That is, considering a set of elementary events, we find that some event e occurred with probability pe. Classical probability arises due to a lack of knowledge on the part of the modeler. The act of measurement merely reveals an existing state of affairs; it does not interfere with the results.

In contrast, quantum models use variables and spaces that are defined with respect to a particular context (although this is often done implicitly). Thus, in specifying that an electron has spin “up” or “down,” we are referring to experimental scenarios (e.g., Stern-Gerlach arrangements and polarizers) that denote the context in which a measurement occurred. This is an important subtlety, as many experiments have shown that it is impossible to attribute a pre-existing reality to the state that is measured; measurement necessarily involves an interaction between a state and the context in which it is measured, and this is traditionally modeled in quantum theory using the notion of projection. The state |Ψ〉 representing some aspect of interest in our system is written as a linear superposition of a set of basis states {|ϕi〉} in a Hilbert space, denoted , which allows us to define notions such as distance and inner product. In creating this superposition we weight each basis state with an amplitude term, denoted ai, which is a complex number representing the contribution of a component basis state |ϕi〉 to the state |Ψ〉. Hence . The square of the absolute value of the amplitude equals the probability that the state changes to that particular basis state upon measurement. This non-unitary change of state is called collapse. The choice of basis states is determined by the observable, Ô, to be measured, and its possible outcomes oi. The basis states corresponding to an observable are referred to as eigenstates. Observables are represented by self-adjoint operators on the Hilbert space. Upon measurement, the state of the entity is projected onto one of the eigenstates.

It is also possible to describe combinations of two entities within this framework, and to learn about how they might influence one another, or not. Consider two entities A and B with Hilbert spaces and . We may define a basis |i〉A for and a basis |j〉B for , and denote the amplitudes associated with the first as and the amplitudes associated with the second as . The Hilbert space in which a composite of these entities exists is given by the tensor product . The most general state in has the form

This state is separable if . It is inseparable, and therefore an entangled state, if .

In some applications, the procedure for describing entanglement is more complicated than what is described here. For example, it has been argued that the quantum field theory procedure, which uses Fock space to describe multiple entities, gives a kind of internal structure that is superior to the tensor product for modeling concept combination [5]. Fock space is the direct sum of tensor products of Hilbert spaces, so it is also a Hilbert space. For simplicity, this initial application of the quantum formalsm to modeling humor will omit such refinements, but such a move may become necessary in further developments of the model.

Quantum models can be useful for describing situations involving potentiality, in which change of state is nondeterministic and contextual. The concept of potentiality has broad implications across the sciences; for example, every biological trait not only has direct implications for existing phenotypic properties such as fitness, but both enables and constrains potential future evolutionary changes for a given species. The quantum approach been used to model the biological phenomenon of exaptation—wherein a trait that originally evolved for one purpose is co-opted for another (possibly after some modification) [40]. The term exaptation was coined by Gould and Vrba [41] to denote what Darwin referred to as preadaptation1. Exaptation occurs when selective pressure causes this potentiality to be exploited. Like other kinds of evolutionary change, exaptation is observed across all levels of biological organization, i.e., at the level of genes, tissue, organs, limbs, and behavior. Quantum models have also been used to model the cultural analog of exaptation, wherein an idea that was originally developed to solve one problem is applied to a different problem [40]. For example, consider the invention of the tire swing. It came into existence when someone re-conceived of a tire as an object that could form the part of a swing that one sits on. This re-purposing of an object designed for one use for use in another context is referred to as cultural exaptation. Much as the current structural and material properties of an organ or appendage constrain possible re-uses of it, the current structural and material properties of a cultural artifact (or language, or art form, etc.) constrain possible re-uses of it. We suggest that incongruity humor constitutes another form of exaptation; an ambiguous word, phrase, or situation, that was initially interpreted one way is revealed to have a second, incongruous interpretation. Thus, it is perhaps unsurprising that, as with other forms of exaptation, a quantum model is explored.

4. A Quantum Inspired Model of Humor

A quantum theory of humor (QTH) could potentially inherit several core concepts from previous cognitive theories of humor while providing a unified underlying model. Considering the past work discussed in Section 2, it seems reasonable to focus on the notion that cognitive humor involves an ambiguity brought on by the bisociation of internally consistent but mutually incongruous schemas. Thus, cognitive humor appears to arise from the double think that is brought about by being forced to reconsider some currently held interpretation of a joke in light of new information: a frame shift. Such an insight opens humor upto quantum-like models, as a frame shift of an ambiguous concept is well modeled by the notion of a quantum superposition described using two sets of incompatible basis states within some underlying Hilbert space structure.

In what follows we sketch out a preliminary quantum inspired model of humor and discuss what would be required for a full-fledged formal QTH. Next, we outline a study aimed at discovering whether humor behaves in a quantum-like manner. The last section discusses how the QTH opens up avenues for future investigation in a field that to date has not been well modeled.

4.1. The Mathematical Structure of QTH

We start our journey toward a QTH by building upon an existing model of conceptual combination [8]: the State–COntext–Property (SCOP) model. As per the standard approach used in most quantum-like models of cognition, |Ψ〉 represents the state of an ambiguous element, be it a word, phrase, object, or something else, and its different possible interpretations are represented by basis states. Core to the SCOP model is a treatment of the context in which every measurement of a state occurred, and the resultant property that was measured. These three variables are stored as a triple in a lattice.

4.1.1. The State Space

Following Aerts and Gabora [6], the set of all possible interpretation states for the ambiguous element of a joke is given by a state space Σ. Specific interpretations of a joke are denoted by |p〉, |q〉, |r〉, · · · ∈ Σ which form a basis in a complex Hilbert space . Before the ambiguous element of the joke is resolved, it is in a state of potentiality, represented by a superposition state of all possible interpretations. Each of these represents a possible understanding arising due to activation of a schema associated with a particular interpretation of an ambiguous word or situation. The interpretations that are most likely are most heavily weighted. The amplitude term associated with each basis state represented by a complex number coefficient ai gives a measure of how likely an interpretation is given the current contextual information available to the listener. We assume that all basis states have unit length, are mutually orthogonal, and are complete, thus .

4.1.2. The Context

In the context of a traditional verbal joke, the context consists primarily of the setup, and the setup is the only contextual element considered in the study in Section 5. However, it should be kept in mind that several other contextual factors not considered in our analysis can affect perceived funniness. Prominent amongst these is the delivery; the way in which a joke is delivered can be everything when it comes to whether or not it is deemed funny. Other factors include the surroundings, the person delivering the joke, the power relationships among different members of the audience, and so forth.

As a first step, we might represent the set of possible contexts for a given joke as . Each possible interpretation of a joke comes with a set of properties (i.e., features or attributes), which may be weighted according to their relevance with respect to this contextual information. The weight (or renormalized applicability) of a certain property given a specific interpretation |p〉 in a specific context is given by ν. For example, ν(p, f1) is the weight of feature fi for state |p〉, which is determined by a function from the set to the interval [0, 1]. We write:

4.1.3. Transition Probabilities

A second function μ describes the transition probability from one state to another under the influence of a particular context. For example, μ(q, e, p) is the probability that state |p〉 under the influence of context ci changes to state |q〉. Mathematically, μ is a function from the set to the interval [0, 1], where μ(q, e, p) is the probability that state |p〉 under the influence of context |e〉 changes to state |q〉. We write:

Thus, a first step toward a full quantum model of humor consists of the 3-tuple , and the functions ν and μ. Next we address a key question that should be asked of any cognitive theory of humor: what is the underlying cognitive model of the funniness of a joke?

4.2. The Humor of a Joke

As the listener hears a joke, more context is provided, and in our model the listener's understanding evolves according to the transition probabilities associated with the cognitive state and the emerging context. When the listener hear the joke a bisociation of meaning is percieved; that is, the listener realizes that a second way of interpreting it is possible. A projective measurement onto a funniness frame is the mechanism that we use to model the likelihood that a given joke is considered funny.

Thus, in our model, funniness plays the role of a measurement operator, and it is affected by the shift that occurs in the understanding of a joke with respect to two possible framings: one created by the setup, and one by the punchline. The probability of a joke being regarded as funny or not is proportional to the projection of the individual's understanding of the joke (|Ψ〉) onto a basis representing funniness. This means that the probability of a joke being considered as funny, pF is given by a projection onto the |1〉 axis in , a two-dimensional Hilbert sub-space where |0〉 represents “not funny” and |1〉 represents “funny.”

Similarly, the probability of a joke being regarded as not funny is represented by

Note that |Ψ〉 evolves as the initial conceptualization of the joke is reinterpreted with respect to the frame of the punchline. This is a difficult process to model, and we consider the work in this paper to be an early first step toward an eventually more comprehensive theory of humor that includes predictive models.

We now present two examples in which specific instances of humor are considered within the perspective of this basic quantum inspired model. First the approach is applied to a pun. Second, the approach is applied to a cartoon that is a frame blend. Both scenarios will help to deepen our understanding of the significant complexity of humor, and the difficulties associated with creating a mathematical model of this important human phenomenon.

4.3. Applying QTH to a Pun

Consider the pun: “Why was 6 afraid of 7? Because 789.” The humor of this pun hinges on the fact that the pronunciation of the number EIGHT, a noun, is identical to that of the verb ATE. We refer to this ambiguous word, with its two possible meanings, as EYT. An individual's interpretation of the word EYT is represented by |Ψ〉, a vector of length equal to 1. This is a linear superposition of basis states in the semantic sub-space which represents possible states (meanings) of the word EYT: EIGHT or ATE2. The interpretation of EYT as a noun, and specifically the number EIGHT, is denoted by the unit vector |n〉. The verb interpretation, ATE, is denoted by the unit vector |v〉. The set {|n〉, |v〉} forms a basis in . Thus, we have now expanded our original two-dimensional funniness space with an additional two-dimensional semantic space, where the full space . We note that these two spaces should not be considered as mutually orthogonal, but that they will overlap. If they were orthogonal then the funniness of a joke would be independent of the interpretation that a person attributes to it.

With this added mathematical structure, we can represent the interpretation of the joke as a superposition state in

where an and av are amplitudes which, when squared, represent the probability of a listener interpreting the joke in a noun or a verb form (|n〉 and |v〉) respectively. This state is depicted in Figure 1A, which shows a superposition state in the semantic space. When given no context in the form of the actual presentation of the joke, these amplitudes represent the prior likelihood of a listener interpreting the uncontextualized word (i.e., EYT) in either of the noun or verb senses (e.g., a free association probability; see [12] for a review). However, we would expect to see these probabilities evolving throughout the course of the pun as more and more context is provided (in the form of additional sentence structure). Throughout the course of the joke, the state vector |Ψ〉 therefore evolves to a new position in .

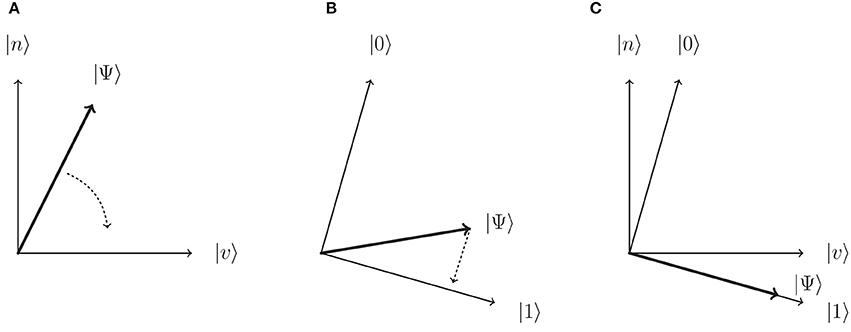

Figure 1. The humor of a joke can be explained as arising from a measurement process that occurs with respect to two incompatible frames. Using the example of the pun, (A) the meaning of the set-up is reinterpreted with EYT updating toward the interpretations ATE. (B) Funniness is then treated as a measurement, with the probability of funniness being judged with respect to a projection on the {|0〉, |1〉} basis. In this case there is a large probability of the joke being considered funny due to the dominant component of the projection of |Ψ〉 lying on the |1〉 axis. (C) The cognitive state of the subject then collapses to the observed state (i.e., funny or not).

Since the set-up of the joke,“Why was 6 afraid of 7?,” contains two numbers, it is likely that the numbers interpretation of EYT is activated (a situation represented in Figure 1A). The listener is biased toward an interpretation of EYT in this sense, and so we would expect that an >> av. However, a careful listener will feel confused upon considering this set-up because we do not think of numbers as beings that experience fear. This keeps the interpretation of EYT shifted away from an equivalence with the eigenvector |n〉. As the joke unfolds, the predator interpretation that was hinted at in the set-up by the word “afraid,” and reinforced by “789,” activates a more definite alternative meaning, ATE, represented by |v〉. This generates an alternative interpretation of the punchline: that the number 7 ate the number 9. The cognitive state |Ψ〉 has evolved to a new position in , a scenario that is represented in Figure 1B. At this point a measurement occurs: the individual either considers the joke as funny or not within the context represented by the funniness sub space , and a collapse to the relevant funniness basis state occurs (see Figure 1C). Note that this final state still contains a superposition within the meaning subspace —the funniness judgment merely shifts the interpretation of the joke, it does not eliminate the bisociation. Rather, it depends upon it.

If we consider the set of properties associated with EYT then we would expect to see two very different prototypical characteristics associated with each interpretation. For example, the EIGHT interpretation is difficult to map into properties such as “food” denoted f1, and “not living” denoted f2 (since when something is eaten it is usually no longer alive). Because “food” and “not living” are not properties of EIGHT, ν(p, f0) << ν(n, f0), and similarly ν(p, f1) << ν(n, f1). However, “food” and “not living” are properties of EYT, ν(p, f0) << ν(v, f0), and similarly ν(p, f1) << ν(v, f1).

We can now start to construct a model of humor that could be correlated with data. If jokes satisfy the law of total probability (LTP) then their funniness should satisfy the distributive axiom, which states that the total probability of some observable should be equal to the sum of the probabilities of it under sets of more specific conditions. Thus, considering a funniness observable ÔF (with eigenstates {|1〉, |0〉} and the semantic observable ÔM (with a simplified two eigenstate structure representing two possible meanings that could be attributed to the joke). We can take the spectral decomposition of , where are eigenvalues of the two eigenstates . Doing this, we should find that if this system satisfies the LTP then the probability of the joke being judged as funny is equal to the sum of the probability of it being judged funny given either semantic interpretation

We can manipulate the interpretation that a participant is likely to attribute to a joke by changing the semantics of the joke itself. Thus, changing the joke should change the semantics, and so affect the humor that is attributed to the joke. We shall return to this idea in Section 5.

This section has demonstrated that a formal approach to concept interactions that has been previously shown to be consistent with human data [5] can be adapted to the simultaneous perception of incongruous meanings of an ambiguous word or phrase in the understanding of a pun.

4.4. Applying QTH to a Frame Blend

Although our first example used a pun for simplicity, we believe that quantum inspired models may also be useful for more elaborate forms of humor, such as jokes and cartoons referred to as frame blends. A frame blend involves the merging of incongruous frames of reference [42]. A common example of a frame blend is a cartoon in which animals are engaged in some kind of human behavior (such as a cartoon of a cow with all her teats pierced saying “Just gotta be me”). In a frame blend rather than being led “down the garden path” by the setup and subsequent re-interpretation in light of the punchline, the humor results from the simultaneous presentation of seemingly incompatible frames. Using QTH, the two interpretations of the incongruous situation would be designated by the unit vectors {|d〉, |o〉}. The cognitive state of perceiving the blended frames is represented as a superposition of the two frames. As with phenomena such as conceptual combination, there are likely to be constraints on how frames can be successfully blended, and it will be necessary to consider this when constructing models of frame blends. We reserve further exploration of this interesting class of humor for future work.

5. Probing the State Space of Humor

Returning to the question raised by Equation (7), a QTH should be justified by considering whether humor does indeed violate the Law of Total Probability (LTP) [3]. However, the complexity of language makes it difficult to test how humor might violate the LTP using a method similar to those followed for decision making [11]. Past work on humor is unlikely to yield the data required to perform tests such as this. For example, we currently have no experimental understanding of how the semantics of a joke interplays with its perceived funniness. It seems reasonable to suppose that the two are related, but how? We are not aware of any data that provide a way to evaluate this relationship. This is problematic, as there are a number of interdependencies in the framing of a joke that make it difficult to construct a model (even before considering factors such as the context in which the joke is made, and the socio-cultural background of the teller and the listener). In this section we present results from an exploratory study designed to start unpacking whether humor should indeed be considered within the framework of quantum cognition. As an illustrative example, consider the following joke:

VO: “Time flies like an arrow. Fruit flies like a banana.”

As with the joke discussed in Section 4.3, the humor arises from the ambiguity of the words FRUIT and FLIES. The first frame (F1, the set-up), leads one to interpret FLIES as a verb and LIKE as a preposition, but the second frame (F2, the punchline), leads one to interpret FRUIT FLIES as a noun and LIKE as a verb. A QTH must be able to explain how the funniness of the joke depends upon a shift in the semantic understanding of the two frames, F1 and F2.

We now outline a preliminary study that has helped us to explore the state space of humor.

5.1. Stimuli

We collected a set of 35 jokes and for each joke we developed a set of joke variants. A VS variant consisted of the set-up only for the original, VO. Thus, the VS variant of the VO joke is

VS: “Time flies like an arrow.”

A VP variant consists of the original punchline only. Thus, the VP variant of the VO joke is

VP: “Fruit flies like a banana.”

We then considered the notion of a congruent punchline as one that does not introduce a new interpretation or context for an ambiguous element of the set-up (or punchline). Congruence was achieved by modifying the set-up to make it congruent with the punchline, or by modifying the punchline to make it congruent with the set-up. Thus, if the original set-up makes use of a noun, then so does a congruent modification (and similarly for the punchline).

A CP variant consists of the original set-up followed a congruent version of the punchline. Thus, a CP variant of the O joke is:

CP: “Time flies like an arrow; time flies like a bird.”

A CS variant consists of the original punchline preceded by a congruent version of the set-up. Thus, a CS variant of the O' joke is

CS: “Horses like carrots; fruit flies like a banana.”

For some jokes we had a fifth kind of variant. A IS variant consists of the original set-up followed an incongruent version of the punchline that we believed was comparable in funniness to the original. Thus, considering the joke discussed in Section 4.3:

O: “Why was 6 afraid of 7? Because 789.”

A IS variant of this joke is:

IS: “Why was 6 afraid of 7? Because 7 was a six offender.”

Thus the stimuli consisted of a questionnaire containing original jokes, and the above variants presented in randomized order. The complete collection of jokes and their variants is presented in the Appendix (Supplementary Material).

5.2. Participants

The participants in this study were 85 first year undergraduate students enrolled in an introductory psychology course at the University of British Columbia (Okanagan campus). They received partial course credit for their participation.

5.3. Procedure

Participants signed up for the study using the SONA recruitment system, and subsequently responded at their convenience to an online questionnaire hosted by FluidSurveys. They were informed that the study was completely voluntary, and that they were free to withdraw at any point in time. They were also informed that the researcher would not have any knowledge of who participated in the study, and that their participation would not affect their standing in the psychology class or relationship with the university. Participants were told that the purpose of the study was to investigate humor, and to help contribute to a better understanding the cognitive process of “getting” a joke. Participants were asked to fill out consent forms. If they agreed to participate, they were provided a questionnaire consisting of a series of jokes and joke variants (as described above) and asked to rate the funniness of each using a Likert scale, from 1 (not funny) to 5 (hilarious). The questionnaire took approximately 25 min to complete. They received partial course credit for their participation.

5.4. Results

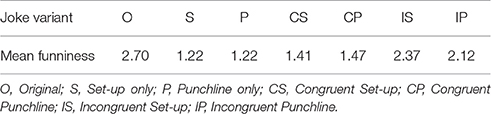

The mean funniness ratings across all participants for the entire collection of jokes and their variants (as well as the jokes and variants themselves) is provided in the Appendix (Supplementary Material). Table 1 provides a summary of this information (the mean funniness rating of each kind of joke variant across all participants) aggregated across all joke sets. As expected, the original joke (O) was funniest (mean funniness = 2.70), followed by those jokes that had been intentionally modified to be funny: Incongruent Setup (IS) (mean funniness = 2.37) and Incongruent Punchline (IP) (mean funniness = 2.12). Next in funniness were the jokes that had been modified to eradicate the incongruency and thus the source of the humor: Congruent Setup (CS) (mean funniness = 1.41) and Congruent Punchline (CP) (mean funniness = 1.47). The joke fragments without a counterpart–i.e., either Setup (S) or Punchline (P) alone–were considered least funny of all (the mean funniness of both was 1.22). The dataset is entirely consistent with the view that the humor derives from incongruence due to bisociation.

Table 1. The mean funniness ratings across all participants and all joke sets for each kind of joke variant.

5.5. Toward a Test of the QTH

Recall that the Law of Total Probability (LTP) as represented by Equation (7) suggests that the mean funniness of a joke should be equal to the sum of its funniness as judged under all possible semantic interpretations. This is not an equality that we can directly test given our current understanding of language and how it might interplay with humor. However, the dataset reported here gives us some initial ways to address this. With a methodology for converting the Likert scale ratings into projective measurements of a joke being funny or not, we can start to consider the relative frequency that an original joke is judged as funny and compare this result with the individual components.

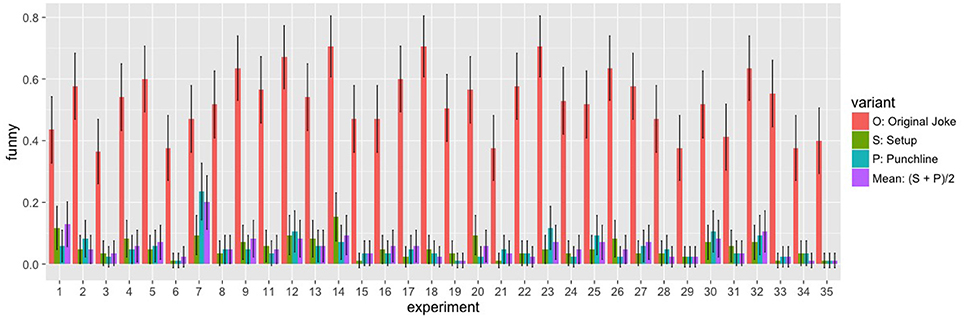

We start by translating the Likert scale responses into a simplified measurement of funniness, by mapping the funniness ratings into a designation of funny or not. In order to run a quick comparison between the relative frequencies that participants decided the full joke (VO) was funny when compared to the components of the joke (VS and VP), we took the mean value of the components for each subject. Given that puns are not generally considered particularly funny (a result backed up by our participant ratings) we used a fairly low threshold value of 2.5 (i.e., if the mean was less than 2.5 then the components were judged as unfunny, and vice versa). Exploring the results of this mapping gives us the data reported in Figure 2 for the VO, VS and VP variants of the jokes, listing the frequency at which participants judged the joke and subcomponents funny. A mean value for the joke fragments is also presented. All data uses confidence intervals at the 95% level.

Figure 2. A comparison of the frequency with which a specific joke and its fragments are considered funny for participants in the pilot trial (using a threshold value of 2.5, n = 85). A mean of the set-up and the punchline variants (VS and VP) is also given. Confidence intervals are set at 95%.

We see a significant discrepancy between the funniness of the original and the combined funniness of its components. This is not a terribly surprising result; jokes are not funny when the set-up is not followed by the punchline, and participants usually rated VS and VP variants as unfunny (i.e., scoring them at 1). Table 2 in the Appendix (Supplementary Material) shows that in the participant pool of 85, the set-up and punchline variants of the joke rarely had a mean funniness rating above 1.5. However, to extract a violation of the LTP for this scenario, we would need to construct expressions such as the following

How precisely could such a relationship be tested? Two forms of data are required to test whether the simple puns used in our experiment actually violate the LTP:

1. Funniness ratings: These are the probabilities regarding the probability that different components of the joke are considered funny (the whole joke (p(F)); just the setup (p(F|EIGHT)); and just the punchline (p(F|ATE)); and

2. Semantic probabilities: These list the probability of EYT being interpreted as EIGHT: p(EIGHT), or ATE: p(ATE), within the context of the specific joke fragment.

We have demonstrated a method for extracting the funniness ratings above. How might we obtain data for the semantic probabilities? We must consider the precise interpretation of what these probabilities might actually be. Firstly, we note that it seems likely participants will interpret just a set-up or a punchline in the sense that the fragment represents. The bisociation that humor relies upon is not present for a fragment, and so a person hearing a fragment will be primed by its surrounding context toward interpreting an ambiguous word in precisely the sense intended for that fragment. Indeed, the incongruity that results from having to readjust the interpretation of the joke, and the resulting bisociation, lies at the very base of the humor that arises. Free association probabilities will not give these values. To test the LTP, it would be necessary to extract information about how a participant is interpreting core terms in the joke as it progresses; some form of nondestructive measurement is required, and a new experimental protocol will have to be defined. We reserve this for future work.

However, the significant difference between the rated funniness of the fragments and that of the original joke allows us to formulate an alternative mechanism for testing equations of the form (7) and (8). We can do this by asking whether there is any way in which the semantic probabilities could have values that would satisfice the LTP? An examination of Figure 2 for the setup and punchline variants of the jokes suggests that there is no way in which to chose semantic probabilities that will satisfy the LTP. Thus, we have preliminary evidence that humor should perhaps be treated using a quantum inspired model.

6. Discussion

It would appear that there is some support for the hypothesis that the humor arising from bisociation can be modeled by a quantum inspired approach. Furthermore, the experimental results presented in section 5 suggest that this model might more appropriate than one grounded in classical probability. However, much work remains to be completed before we can consider these findings anything but preliminary.

Firstly, the model presented in Section 4 is simple, and will need to be extended. While an extension to more senses for an ambiguous element of a joke is straightforward with a move to higher dimensions, the model is currently not well suited to the set of variants discussed in Section 5.3. A model that can show how they interrelate, and how their underlying semantics affects the perceived humor in a joke is desirable. Furthermore, the funniness of the joke was simplistically represented by a projection onto the “funny”/“not funny” axis. A more theoretically grounded treatment of the Likert data is desirable. For example, the current threshold value of 2.5 was chosen somewhat arbitrarily [although could be justified by a consideration of the mean values for funniness scores reported in the Appendix (Supplementary Material)—see Table 2]. A more systematic way of considering the Likert scale measures to allow for a normalization of funniness ratings at the level of an individual is also desirable. As a highly subjective phenomenon, funniness is liable to be judged by different individuals inconsistently and so it will be important that we control for this effect in comparing Likert responses among individuals.

Considering experimental results, the sample size of the data set is somewhat small (85 participants), although our funniness ratings appear to be reasonably stable for this cohort. A more concerning problem revolves around the construction of a LTP relationship for our simple model. There are many alternative ways in which a LTP could be constructed for puns, and more sophisticated models need to be investigated before we can be confident that our results conclusively demonstrate that humor must be modeled using a quantum inspired approach. In particular, we require a more sophisticated method that facilitates the extraction of data about the semantics attributed by a participant to a joke. A two stage protocol may be the answer for obtaining the necessary semantic information for a more rigorously founded test of the violation of LTP. It would be useful to construct a systematic study of the manner in which adjusting the congruence of the set-ups and punchlines influences perception of the joke. The quantum inspired semantic space approaches of Van Rijsbergen [13] and Widdows [43] may prove fruitful in this regard, as they would facilitate the creation of similarity models such as those explored by Aerts et al. [44] and Pothos and Trueblood [45].

In summary, humor is complex, and it will take an ongoing program of research to understand the interplay between the semantics of a joke and its perceived funniness. However, at this point we might pause to consider the broader question of why humor might be better modeled by a quantum inspired approach than by one grounded in classical probability? To this end we return to the discussion of Section 3. As we saw, the humor of a pun involves the bisociation of incongruent frames, i.e., re-viewing a setup frame in light of new contextual information provided by a punchline frame. Moreover, the broader contextuality of humor means that even the funniest of jokes can become markedly unfunny if delivered in the wrong way (e.g., a monotone voice), or in the wrong situation (e.g., after receiving very bad news). Funniness is not a pre-existing “element of reality” that can be measured; it emerges from an interaction between the underlying nature of the joke, the cognitive state of the listener, and other social and environmental factors. This makes the quantum formalism an excellent candidate for modeling humor, as this interaction is well described by the concept of a vector state embedded in a space which is represented using basis states that can be reoriented according to the framing of the joke. However, this paper only provides a preliminary indication that a QTH may indeed provide a good theoretical underpinning for this complex process. Much more work remains to be done.

7. Conclusions

This paper has provided a first step toward a quantum theory humor (QTH). We constructed a model where frame blends are represented in a Hilbert space spanned by two sets of basis states, one representing the ambiguous framing of a joke, and the other representing funniness. The process of “getting a joke” then consists of a dual stage scenario, where the cognitive state of a person evolves toward a re-interpretation of the meaning attributed to the joke, followed by a measurement of funniness. We conducted a study in which participants rated the funniness of jokes as well as the funniness of variants of those jokes consisting of setting or punchline by alone. The results demonstrate that the funniness of the jokes is significantly greater than that of their components, which is not particularly surprising, but does show that there is something cognitive taking place above and beyond the information content delivered in the joke. A preliminary test to see whether the humor in a joke violates the law of total probability appears to suggest that there is reason to suppose that a quantum inspired model is indeed appropriate.

Our QTH is not proposed as an all-encompassing theory of humor; for example, it cannot explain why laughter is contagious, or why children tease each other, or why people might find it funny when someone is hit in the face with a pie (and laugh even if they know it will happen in advance). It aims to model the cognitive aspect of humor only. Moreover, despite the intuitive appeal of the approach, it is still rudimentary, and more research is needed to determine to what extent it is consistent with empirical data. Nevertheless, we believe that the approach promises an exciting step toward a formal theory of humor. It is hoped that future research will build upon this modest beginning.

Ethics Statement

This research was approved by the Behavioral Research Ethics Board at the University of British Columbia (Okanagan Campus).

Author Contributions

LG had the idea for the paper and designed and conducted the study. Both authors contributed equally to all other aspects of the research and the writing of the paper.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant (62R06523) from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada. We are grateful to Samantha Thomson who assisted with the development of the questionnaire and the collection of the data for the study reported here.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fphy.2016.00053/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^The terms exaptation, preadaptation and co-option are often used interchangeably.

2. ^We acknowledge that other interpretations are possible, and so this is a simplified model. It is straightforward to extend the model into higher dimensions by adding further interpretations as basis states.

References

1. Veale T, Brone G, Feyaerts K. Humour as the killer-app of language: a view from Cognitive Linguistics. In: Brone G, Feyaerts K, Veale T, editors. Cognitive Linguistics and Humor Research. Berlin; Boston, MA: De Gruyter (2015). p. 1–11. doi: 10.1515/9783110346343-001

2. Khrennikov AY. Ubiquitous Quantum Structure: From Psychology to Finance. Berlin; Heidelberg: Springer (2010). doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-05101-2

3. Busemeyer J, Bruza P. Quantum Models of Cognition and Decision. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (2012). doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511997716

4. Asano M, Khrennikov A, Ohya M, Tanaka Y, Yamato I. Quantum Adaptivity in Biology: From Genetics to Cognition. Dordrecht: Springer (2015).

5. Aerts D. Quantum structure in cognition. J Math Psychol. (2009) 53:314–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jmp.2009.04.005

6. Aerts D, Gabora L. A theory of concepts and their combinations I: the structure of the sets of contexts and properties. Kybernetes (2005) 34:167–91. doi: 10.1108/03684920510575799

7. Aerts D, Gabora L. A theory of concepts and their combinations II: a Hilbert space representation. Kybernetes (2005) 34:192–221. doi: 10.1108/03684920510575807

8. Gabora L, Aerts D. Contextualizing concepts using a mathematical generalization of the quantum formalism. J Exp Theor Artif Intell. (2002) 14:327–58. doi: 10.1080/09528130210162253

9. Bruza P, Kitto K, Nelson D, McEvoy C. Is there something quantum-like about the human mental lexicon? J Math Psychol. (2009) 53:362–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jmp.2009.04.004

10. Bruza P, Kitto K, Ramm B, Sitbon L. A probabilistic framework for analyzing the compositionality of conceptual combinations. J Math Psychol. (2015) 67:26–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jmp.2015.06.002

11. Pothos EM, Busemeyer JR, Trueblood JS. A quantum geometric model of similarity. Psychol Rev. (2013) 120:679–96. doi: 10.1037/a0033142

12. Nelson DL, Kitto K, Galea D, McEvoy CL, Bruza PD. How activation, entanglement, and search in semantic memory contribute to event memory. Mem Cogn. (2013) 41:717–819. doi: 10.3758/s13421-013-0312-y

13. Van Rijsbergen. The Geometry of Information Retrieval. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (2004).

14. Melucci M. A basis for information retrieval in context. ACM Trans Inf Syst. (2008) 26:14:1–14:41. doi: 10.1145/1361684.1361687

15. Aerts D, Aerts S. Applications of quantum statistics in psychological studies of decision processes. Found Sci. (1994) 1:85–97.

16. Busemeyer JR, Wang Z, Townsend JT. Quantum dynamics of human decision making. J Math Psychol. (2006) 50:220–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jmp.2006.01.003

17. Busemeyer J, Pothos E, Franco R, Trueblood J. A quantum theoretical explanation for probability judgement errors. Psychol Rev. (2011) 118:193–218. doi: 10.1037/a0022542

18. Mogiliansky AL, Zamir S, Zwirn H. Type indeterminacy: a model of the KT (Kahneman–Tversky)-man. J Math Psychol. (2009) 53:349–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jmp.2009.01.001

19. Yukalov VI, Sornette D. Processing information in quantum decision theory. Entropy (2009) 11:1073–120. doi: 10.3390/e11041073

20. Atmanspacher H, Filk T, Römer H. Quantum Zeno features of bistable perception. Biol Cybern. (2004) 90:33–40. doi: 10.1007/s00422-003-0436-4

21. Atmanspacher H, Filk T. The Necker–Zeno model for bistable perception. Top Cogn Sci. (2013) 5:800–17. doi: 10.1111/tops.12044

22. Khrennikov A. Quantum-like model of unconscious–conscious dynamics. Front Psychol. (2015) 6:997. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00997

23. Haven E, Khrennikov A. Quantum Social Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (2013). doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139003261

24. Kitto K, Boschetti F. Attitudes, ideologies and self-organization: information load minimization in multi-agent decision making. Adv Comp Syst. (2013) 16:1350029. doi: 10.1142/S021952591350029X

25. Gabora L. Cognitive Mechanisms Underlying the Origin and Evolution of Culture. Doctoral Thesis. Free University of Brussels (2001).

26. Gabora L, Aerts D. A model of the emergence and evolution of integrated worldviews. J Math Psychol. (2009) 53:434–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jmp.2009.06.004

27. Gabora L, Kitto K. Concept combination and the origins of complex cognition. In: Swan E, editor. Origins of Mind: Biosemiotics Series, Vol. 8. Berlin: Springer (2013). p. 361–82. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-5419-5_19

28. Gabora L, Carbert N. A Study and Preliminary Model of Cross-domain Influences on Creativity. Austin TX: Cognitive Science Society (2015).

32. Shultz TR. Order of cognitive processing in humour appreciation. Can J Psychol. (1974) 28:409–20. doi: 10.1037/h0082006

33. Suls JM. A two stage model for appreciation ofjokes and cartoons: an information-processing analysis. In: Goldstein JH, McGhee PE, editors. The Psychology of Humor: Theoretical Perspectives und Empirical Issues. New York, NY: Academic Press (1972). p. 81–100. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-288950-9.50010-9

34. Martin RA. The Psychology of Humor: An Integrative Approach. Burlington, MA: Elsevier Academic Press (2007).

35. McGraw AP, Warren C. Benign violations: making immoral behavior funny. Psychol Sci. (2010) 21:1141–9. doi: 10.1177/0956797610376073

36. Reyes A, Rosso P, Veale T. A multidimensional approach for detecting irony in Twitter. Lang Resour Eval. (2013) 47:239–68. doi: 10.1007/s10579-012-9196-x

37. Binsted K, Pain H, Ritchie G. Childrens evaluation of computer-generated punning riddles. Pragmat Cogn. (1997) 5:305–354. doi: 10.1075/pc.5.2.06bin

38. Valitutti A, Toivonen H, Doucet A, Toivanen JM. “Let everything turn well in your wife”: generation of adult humor using lexical constraints. In: Proceedings of the 51st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics. Association for Computational Linguistics Sofia: Association for Computational Linguistics (2013). p. 243–8.

40. Gabora L, Eric S, Kauffman S. A quantum model of exaptation: incorporating potentiality into biological theory. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. (2013) 113:108–116. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2013.03.012

41. Gould SJ, Vrba ES. Synopsis of a workshop on humor and cognition. Paleobiology (1982) 8:4–15. doi: 10.1017/S0094837300004310

44. Aerts S, Kitto K, Sitbon L. Similarity metrics within a point of view. In: Song D, Melucci M, Frommholz, I, Zhang, P, Wang, L, Arafat, S, editors. Quantum Interaction 5th International Symposium, QI 2011, June 26-29, 2011, Revised Selected Papers. Vol. 7052 of LNCS. Aberdeen: Springer (2011). p. 13–24. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-24971-6_3

Keywords: bisociation, context, humor, incongruity, law of total probability, pun, quantum cognition, quantum interaction

Citation: Gabora L and Kitto K (2017) Toward a Quantum Theory of Humor. Front. Phys. 4:53. doi: 10.3389/fphy.2016.00053

Received: 01 September 2016; Accepted: 21 December 2016;

Published: 26 January 2017.

Edited by:

Andrei Khrennikov, Linnaeus University, SwedenReviewed by:

Haroldo Valentin Ribeiro, Universidade Estadual de Maringá, BrazilRaimundo Nogueira Costa Filho, Federal University of Ceará, Brazil

Irina Basieva, Graduate School for the Creation of New Photonics Industries, Russia

Copyright © 2017 Gabora and Kitto. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Liane Gabora, liane.gabora@ubc.ca

Liane Gabora

Liane Gabora Kirsty Kitto

Kirsty Kitto