- 1Department of Psychology, University of Salzburg, Salzburg, Austria

- 2Centre for Cognitive Neuroscience, University of Salzburg, Salzburg, Austria

A commentary on

Questionnaire and behavioral task measures of impulsivity are differentially associated with body mass index: a comprehensive meta-analysis

by Emery, R. L., and Levine, M. D. (in press). Psychol. Bull. doi: 10.1037/bul0000105

In a recent article, Emery and Levine (in press) report on a meta-analysis examining the relationship between impulsivity measures and body mass index (BMI). They found that impulsivity relates positively, but weakly, to BMI and that behavioral measures of impulsivity produced larger effects than questionnaire measures. Impulsivity domains that assessed disinhibited behaviors, attentional deficits, impulsive decision-making, and cognitive inflexibility produced significant, but small effect sizes. Effect sizes for impulsivity domains related to extraversion/positive emotionality, neuroticism/negative emotionality, and inhibition were not significant. Therefore, these meta-analytic results provide strong support for and are in line with prior observations about the very small correlation between impulsivity and BMI and about the relevance of differentiating between specific impulsivity domains when examining relationships with BMI (Mobbs et al., 2010; Lawyer et al., 2015; Meule and Blechert, 2016; VanderBroek-Stice et al., 2017). This commentary intends to highlight two additional aspects that seem relevant when examining the relationship between impulsivity and BMI. Specifically, it is argued that there are (1) indirect effects of impulsivity on BMI through eating behavior (mediation) and (2) interaction effects between different impulsivity domains or between impulsivity and eating-related constructs on BMI (moderation). Both of these effects cannot be observed by testing single correlations between impulsivity measures and BMI. In addition, both effects can be found even when impulsivity and BMI appear to be uncorrelated at first glance.

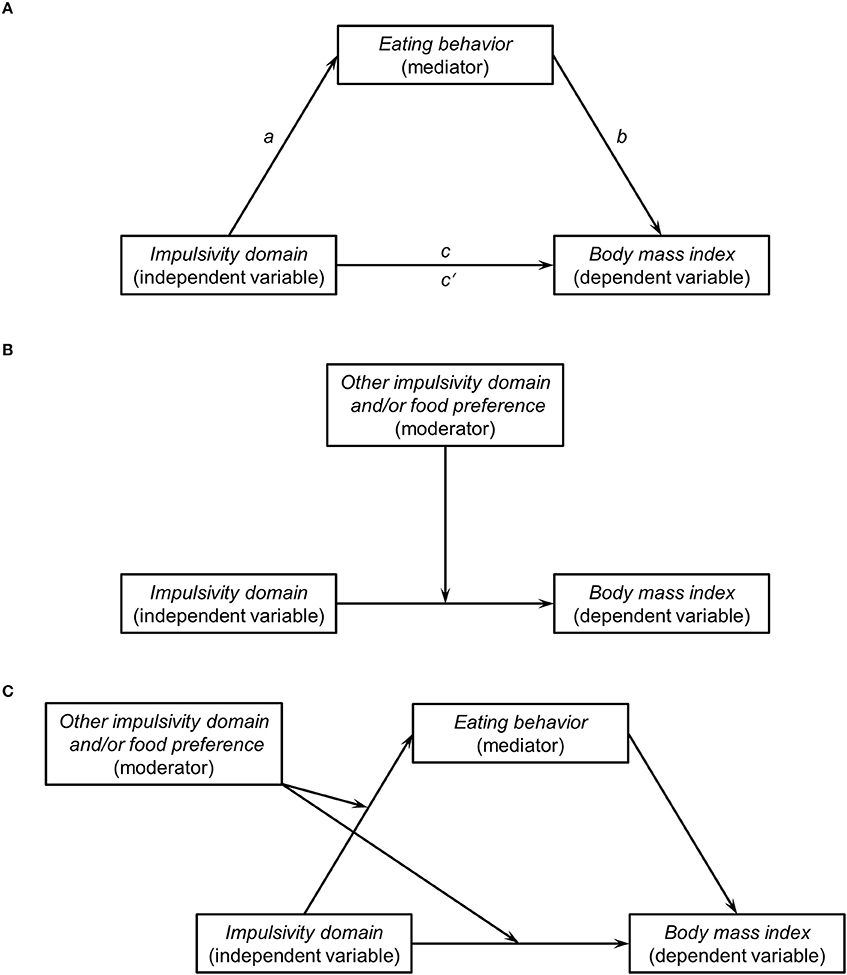

Indirect effects refer to a possible causal chain that describes how (i.e., through which mechanism) an antecedent variable (X) is linked to a consequent variable (Y) through an intermediary variable (i.e., mediator, M). The general association between X and Y without considering M is called the total effect. The presence of a total effect (e.g., a significant correlation coefficient between X and Y), however, is not relevant to establishing mediation. That is, it is indeed possible to establish an indirect effect despite no total effect (Zhao et al., 2010; Hayes, 2013; Hayes and Rockwood, in press). For example, it could be that two or more indirect paths carry the effect from X through Y that operate in opposite directions and, thus, can cancel each other out and produce a non-significant total effect (MacKinnon et al., 2000; Hayes, 2009). When a person has an impulsive personality, body fat does not magically increase simply because of that. Instead, impulsivity most likely translates into higher BMI through higher calorie intake (Figure 1A). This is indeed what has been found in recent (yet cross-sectional) studies: there was no total effect of impulsivity on BMI, but an indirect effect of impulsivity on BMI through variables that are associated with increased food consumption (e.g., more frequent and intense food cravings or higher addiction-like eating behavior; Murphy et al., 2014; Meule and Blechert, 2017; VanderBroek-Stice et al., 2017). Future studies may identify additional indirect effects of impulsivity on BMI that may be of opposite direction. For example, impulsivity-associated constructs such as extraversion and sensation seeking have been found to correlate with higher physical activity (Rhodes and Smith, 2006; Leasure and Neighbors, 2014; Wilson and Dishman, 2015; Artese et al., 2017). Thus, physical activity could be a potential mechanism that may link higher impulsivity with lower BMI and, thus, may explain non-significant total effects of impulsivity on BMI.

Figure 1. (A) Hypothetical simple mediation model that includes an indirect effect of an impulsivity domain on body mass index (BMI) through eating behavior. The variable impulsivity domain may represent constructs such as disinhibited behaviors, attentional deficits, impulsive decision-making, or cognitive inflexibility (Emery and Levine, in press). The variable eating behavior may represent habitual food consumption (e.g., as measured with a food frequency questionnaire) or constructs such as disinhibited eating, trait food craving, food addiction, binge eating or similar eating styles that are associated with consumption of energy-dense and/or large amounts of food (e.g., Meule and Blechert, 2017; also see Vainik et al., 2015 for a discussion of different eating-related traits that seem to represent the same underlying concept). Path a represents the relationship between an impulsivity domain and eating behavior. Path b represents the relationship between eating behavior and BMI when controlling for the independent variable. Path c represents the relationship between an impulsivity domain and BMI without controlling for the mediating variable (total effect). Path c' represents the relationship between an impulsivity domain and BMI when controlling for the mediating variable (direct effect). The product of a × b is the indirect effect of an impulsivity domain on BMI through eating behavior. The total effect is the sum of the indirect and the direct effect (c = (a × b) + c') and, thus, the presence of a total effect is not a prerequisite for establishing an indirect effect. Therefore, an impulsivity domain may be indirectly associated with BMI through eating behavior, even when the correlation coefficient between that impulsivity domain and BMI (i.e., the total effect) is not statistically significant. (B) Hypothetical moderation model, in which the relationship between an impulsivity domain and BMI depends on a moderating variable. This moderating variable may be another impulsivity domain and/or may be an eating-related variable such as preference for high-calorie foods. Therefore, an impulsivity domain may be associated with BMI as a function of a moderating variable, even when the correlation coefficient between that impulsivity domain and BMI is not statistically significant. (C) Hypothetical moderated mediation model, in which the moderating variable in (B) not only moderates the total effect of an impulsivity domain on BMI, but also moderates the indirect effect of an impulsivity domain on BMI. For example, there may be an indirect effect of an impulsivity domain on BMI through eating behavior, but only at high levels on another impulsivity domain and/or only in individuals that demonstrate a high preference for high-calorie foods. These are just a few examples of how and under which circumstances a high impulsivity may translate into higher BMI as (1) all paths (a, b, and c) can potentially be moderated (and by different variables), (2) paths a and b may include additional mediators that link the independent variable with the mediator and the mediator with the dependent variable (serial mediation), and (3) there may be several mediators that act simultaneously (parallel mediation).

Interaction effects refer to the question about when (i.e., under which circumstances) or for whom an antecedent variable is linked to a consequent variable, contingent on a moderating variable. For example, BMI (or calorie intake) may be particularly high when a person scores high on more than one impulsivity domain (Figure 1B). Furthermore, having an impulsive personality may only lead to weight gain when combined with a strong preference for high-calorie foods (Figure 1B). This has indeed be found in recent studies: one impulsivity domain (attentional impulsivity as measured with the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale) was particularly associated with higher calorie intake, disinhibited eating behaviors, or body fat when individuals also had higher scores on another impulsivity domain (motor impulsivity as measured with the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale), but not when individuals had lower scores on this domain (Kakoschke et al., 2015; Meule and Platte, 2015; Meule et al., 2017). Higher impulsivity predicted higher unhealthy food consumption in the laboratory, but only when participants also demonstrated high food reward sensitivity or implicit preference for high-calorie foods (Friese and Hofmann, 2009; Hofmann et al., 2009; Appelhans et al., 2011). In two longitudinal studies, higher impulsivity prospectively predicted weight gain, but only in participants who showed a high preference or attentional bias for high-calorie foods (Nederkoorn et al., 2010; Meule and Platte, 2016).

In conclusion, the meta-analytic findings by Emery and Levine (in press) demonstrate that the total effect of impulsivity on BMI is very small and that the size of this total effect differs depending on the specific impulsivity domain that is investigated. Because of its small effect size, the relationship between impulsivity and BMI is likely to be non-significant in underpowered studies and researchers will conclude that impulsivity and BMI were unrelated in their respective investigation. As has been highlighted in this commentary, however, there are likely indirect effects of impulsivity on BMI through eating behavior-related variables (Figure 1A) and interaction effects between different impulsivity domains or between impulsivity and eating behavior-related variables (Figure 1B), even when there is no directly observable, significant correlation between the respective impulsivity measure and BMI. Such mediation and moderation effects can also be integrated into one moderated mediation model (Figure 1C; e.g., Meule et al., 2016). Therefore, researchers are encouraged to conduct such analyses, particularly when a correlation between impulsivity and BMI is absent or small. Ideally, testing for such effects will become a default analysis strategy, which will ultimately contribute to generating a comprehensive model of how and when or for whom an impulsive personality poses a risk for becoming overweight or obese.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Appelhans, B. M., Woolf, K., Pagoto, S. L., Schneider, K. L., Whited, M. C., and Liebman, R. (2011). Inhibiting food reward: delay discounting, food reward sensitivity, and palatable food intake in overweight and obese women. Obesity 19, 2175–2182. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.57

Artese, A., Ehley, D., Sutin, A. R., and Terracciano, A. (2017). Personality and actigraphy-measured physical activity in older adults. Psychol. Aging 32, 131–138. doi: 10.1037/pag0000158

Emery, R. L., and Levine, M. D. (in press). Questionnaire and behavioral task measures of impulsivity are differentially associated with body mass index: a comprehensive meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. doi: 10.1037/bul0000105

Friese, M., and Hofmann, W. (2009). Control me or I will control you: impulses, trait self-control, and the guidance of behavior. J. Res. Pers. 43, 795–805. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2009.07.004

Hayes, A. F. (2009). Beyond Baron and Kenny: statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Commun. Monogr. 76, 408–420. doi: 10.1080/03637750903310360

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Hayes, A. F., and Rockwood, N. J. (in press). Regression-based statistical mediation and moderation analysis in clinical research: observations, recommendations, and implementation. Behav. Res. Therapy. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2016.11.001

Hofmann, W., Friese, M., and Roefs, A. (2009). Three ways to resist temptation: the independent contributions of executive attention, inhibitory control, and affect regulation to the impulse control of eating behavior. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 45, 431–435. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2008.09.013

Kakoschke, N., Kemps, E., and Tiggemann, M. (2015). External eating mediates the relationship between impulsivity and unhealthy food intake. Physiol. Behav. 147, 117–121. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2015.04.030

Lawyer, S. R., Boomhower, S. R., and Rasmussen, E. B. (2015). Differential associations between obesity and behavioral measures of impulsivity. Appetite 95, 375–382. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2015.07.031

Leasure, J. L., and Neighbors, C. (2014). Impulsivity moderates the association between physical activity and alcohol consumption. Alcohol 48, 361–366. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2013.12.003

MacKinnon, D. P., Krull, J. L., and Lockwood, C. M. (2000). Equivalence of the mediation, confounding and suppression effect. Prevent. Sci. 1, 173–181. doi: 10.1023/A:1026595011371

Meule, A., and Blechert, J. (2016). Trait impulsivity and body mass index: a cross-sectional investigation in 3073 individuals reveals positive, but very small relationships. Health Psychol. Open 3, 1–6. doi: 10.1177/2055102916659164

Meule, A., and Blechert, J. (2017). Indirect effects of trait impulsivity on body mass. Eat. Behav. 26, 66–69. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2017.01.012

Meule, A., de Zwaan, M., and Müller, A. (2017). Attentional and motor impulsivity interactively predict ‘food addiction’ in obese individuals. Compr. Psychiatry 72, 83–87. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.10.001

Meule, A., Hofmann, J., Weghuber, D., and Blechert, J. (2016). Impulsivity, perceived self-regulatory success in dieting, and body mass in children and adolescents: a moderated mediation model. Appetite 107, 15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2016.07.022

Meule, A., and Platte, P. (2015). Facets of impulsivity interactively predict body fat and binge eating in young women. Appetite 87, 352–357. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2015.01.003

Meule, A., and Platte, P. (2016). Attentional bias toward high-calorie food-cues and trait motor impulsivity interactively predict weight gain. Health Psychol. Open 3, 1–7. doi: 10.1177/2055102916649585

Mobbs, O., Crépin, C., Thiéry, C., Golay, A., and Van der Linden, M. (2010). Obesity and the four facets of impulsivity. Patient Educ. Couns. 79, 372–377. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.03.003

Murphy, C. M., Stojek, M. K., and MacKillop, J. (2014). Interrelationships among impulsive personality traits, food addiction, and body mass index. Appetite 73, 45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.10.008

Nederkoorn, C., Houben, K., Hofmann, W., Roefs, A., and Jansen, A. (2010). Control yourself or just eat what you like? Weight gain over a year is predicted by an interactive effect of response inhibition and implicit preference for snack foods. Health Psychol. 29, 389–393. doi: 10.1037/a0019921

Rhodes, R. E., and Smith, N. E. I. (2006). Personality correlates of physical activity: a review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 40, 958–965. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.028860

Vainik, U., Neseliler, S., Konstabel, K., Fellows, L. K., and Dagher, A. (2015). Eating traits questionnaires as a continuum of a single concept. Uncontrolled eating. Appetite 90, 229–239. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2015.03.004

VanderBroek-Stice, L., Stojek, M. K., Beach, S. R., and MacKillop, J. (2017). Multidimensional assessment of impulsivity in relation to obesity and food addiction. Appetite 112, 59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2017.01.009

Wilson, K. E., and Dishman, R. K. (2015). Personality and physical activity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pers. Individ. Dif. 72, 230–242. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2014.08.023

Keywords: impulsivity, body mass index, mediation, moderation, moderated mediation

Citation: Meule A (2017) Commentary: Questionnaire and behavioral task measures of impulsivity are differentially associated with body mass index: a comprehensive meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 8:1222. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01222

Received: 17 May 2017; Accepted: 04 July 2017;

Published: 21 July 2017.

Edited by:

Caroline Braet, Ghent University, BelgiumReviewed by:

Eva Kemps, Flinders University, AustraliaAnne Roefs, Maastricht University, Netherlands

Katrijn Houben, Maastricht University, Netherlands

Copyright © 2017 Meule. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Adrian Meule, adrian.meule@sbg.ac.at

Adrian Meule

Adrian Meule