- 1Liaquat University of Medical & Health Sciences, Jamshoro, Pakistan

- 2Nassau University Medical Center, East Meadow, NY, United States

- 3Punjab Medical College, Faisalabad, Pakistan

- 4NYU Langone Medical Center, New York, NY, United States

- 5A & L Physicians, New York, NY, United States

- 6Kings County Hospital Center, Brooklyn, NY, United States

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) patients, when in crisis, are frequent visitors of emergency departments (EDs). When these patients exhibit symptoms such as aggressiveness, impulsivity, intense anxiety, severe depression, self-harm, and suicidal attempts or gestures, diagnosis, and treatment of the BPD becomes challenging for ED doctors. This review will, therefore, outline advice to physicians and health-care providers who face this challenging patient population in the EDs. Crisis intervention should be the first objective of clinicians when dealing with BPD in the emergency. For the patients with agitation, symptom-specific pharmacotherapy is usually recommended, while for non-agitated patients, short but intensive psychotherapy especially dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) has a positive effect. Although various psychotherapies, either alone or integrated, are preferred modes of treatment for this group of patients, the effects of psychotherapies on BPD outcomes are small to medium. Proper risk management along with developing a positive attitude and empathy toward these patients will help them in normalizing in an emergency setting after which treatment course can be decided.

Methodology

Using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses methodology (1), a search for relevant published literature was done using PubMed. The key words and phrases used together with Boolean operators included: “borderline personality disorder in emergency department” (Mesh), “borderline personality disorder pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy” (Mesh), “dialectical behavior therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy in borderline personality disorder” (Mesh), borderline personality disorder and cluster B personality disorders (Mesh), “borderline personality disorder and impulsivity, aggression, suicidality” (Mesh). Other relevant studies were found by a review of the primary studies obtained in the search as well as reference tracing of selected articles.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were:

• Any articles that reported the patient of borderline personality disorder (BPD), crisis intervention in the Emergency departments (EDs) and beyond in terms of acute and long-term treatment plan.

• Eligible studies were included if they were observational or interventional in which pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy were investigated as immediate or follow-up treatment.

• We included both observational and interventional studies whether with control groups or not. No restrictions were placed on the control group; we included placebo, treatment as usual, or any unspecific treatment for BPD.

• Only peer-reviewed research studies, which were published in the English. Specific case studies, case letters, and gray literature as well as studies not published in English were excluded.

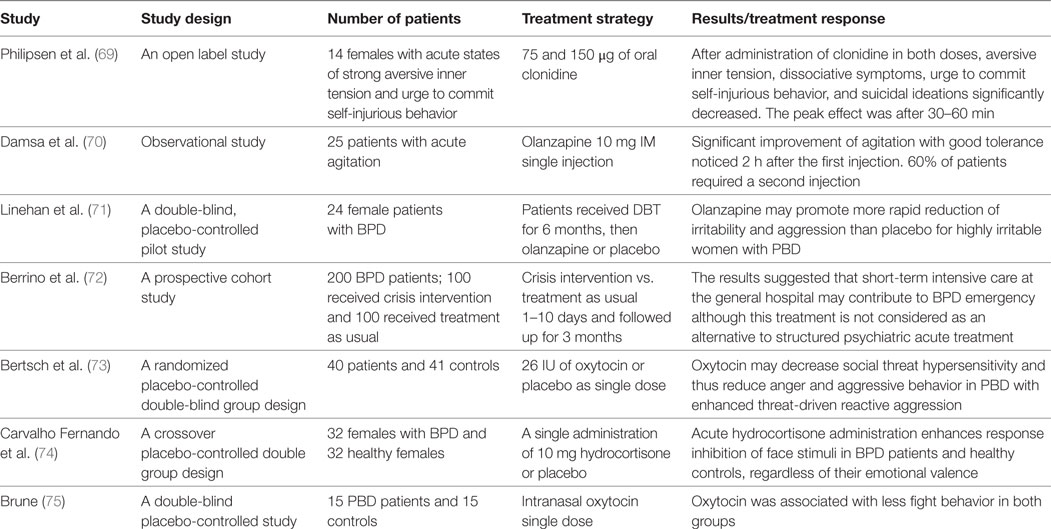

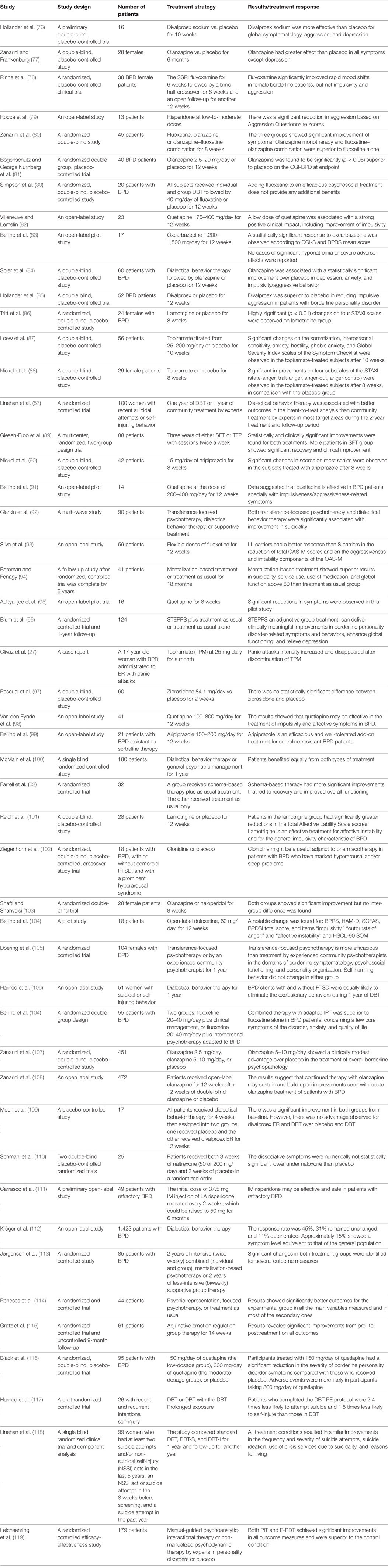

The above-outlined search strategy allowed for the retrieval a total of 396 articles following the removal of duplicates from various sources. The identified results were then reviewed by two independent researchers. From the 396 articles obtained, only 71 studies were relevant to the topic of review. Article relevance was found after looking at the title of the article and reading their abstracts. After a full-text review, 56 of the 71 relevant articles were found and used to extract qualitative data and summarize the findings from this literature review (Tables 1 and 2).

Introduction

The Diagnostic and Statistics Manual for Mental Disorders, fifth edition (2) classifies borderline line personality disorder (BPD) as a cluster B personality disorder and describes it as “a pervasive pattern of instability of interpersonal relationships, self-image, and affects, and marked impulsivity that begins by early adulthood and is present in a variety of contexts” (2). The Genesis of BPD is multifactorial, the biological inheritance, psychological, and social factors are the three major reasons for the development of BPD (3–7). Race, gender, and being socially disadvantageous influence the development of BPD (6–14). Functional impairment is the prime concern associated with the disease (15). BPD was once considered as an untreatable disease; however, the study by Gunderson and colleagues reported a remission rate of about 45% in 2 years and 85% in 10 years, indicating that correct diagnosis, proper, and timely management can allow the patient to live a normal life (15, 16).

Borderline personality disorder is a frequent psychiatric condition encountered in both the hospital and in psychiatric emergencies (17). Approximately 9–27% of agitated emergency patients are diagnosed with the borderline disorder (3, 18, 19). Predominantly, BPD patients visit an ED in the state of crisis, which includes immediate episodes of self-harm, suicidal attempt, aggressiveness, impulsivity, intense anxiety, short-term hallucinations, and delusions (17, 20). Such crises are usually short-lived, but severe in nature, and the intensity varies from person to person. Once the patient has reached the ED, the crisis state is either in the continuation or has subsided keeping the patient in a phase of strong emotional stress, which makes them non-cooperative. With such a heightened stress and difficult situation in the ED, identifying the disease, managing the patient, and defining the course of treatment becomes challenging not only for the attending psychiatrist but also for the accompanying staff. We review the difficulties faced by ED staff including physicians when diagnosing these patients, implementing a treatment regimen.

Diagnostic Difficulty

Accurate diagnosis of the disease is necessary for deciding the future treatment regimen. A patient qualifies as BPD if he or she meets the five criteria out of the nine mentioned in DSM-5 (2). These criteria are: (1) frantic efforts to avoid abandonment; (2) a history of unstable and intense relationships with others; (3) identity disturbance; (4) impulsivity in at least two functional areas such as spending, sex, substance use, eating, or driving; (5) recurrent suicidal threats or behaviors as well as self-mutilation; (6) affective instability with marked reactivity of mood; (7) chronic feelings of emptiness; (8) inappropriate and intense anger or difficulty controlling anger; and (9) transient stress induced paranoid ideation or severe dissociative symptoms. This allows for significant variations in symptoms presentation from one BPD patient to another. Moreover, with overlapping clinical features with bipolar disease, pinpointing BPD becomes even more difficult (12). Although presenting symptoms of both the diseases are similar, their treatment course is completely different (21). The situation is further worsened when the patient in crisis displays a disruptive behavior and is non-cooperative. Thus, physicians are confronted with diagnostic dilemma and frustration. In such a situation, the crisis should be managed to make the patient more cooperative which, in turn, will aid an accurate identification of the disease and deciding the treatment course.

Crisis Intervention in the EDs and Beyond

In a recent Cochrane review, Borschmann et al. defined crisis intervention as “an immediate response by one or more individuals to the acute distress experienced by another individual, which is designed to ensure safety and recovery and lasts not longer than 1 month” (22). Indeed, the priority of the ED physician who encounters a patient with BPD is to address any acute symptoms of distress and to calm the patient. However, the procedure for such crisis intervention is subjective.

In severely agitated patients, calming down them should be the prime focus. Managing agitation can be achieved by different methods such as administering non-specific sedating medication (benzodiazepines and/or antipsychotics), behavioral management, and psychological techniques such as de-escalation or physical restraint (23). Conventionally, benzodiazepines and antipsychotics are administered to control the agitated BPD patients. However, benzodiazepines use may lead to several side effects along with the strong sedation, hypotension, include respiratory depression, while typical antipsychotics cause dysphoria, acute dystonia, and akathisia. Recently, a few studies have reported that atypical antipsychotics such as Olanzapine, Ziprasidone, and Loxapine are more effective for treating acute crisis in BPD patients presenting to the ED (24–29). Intramuscular administration of single dose of olanzapine resulted in fast reduction of agitation in BPD patients and was tolerated well, with only 16% of patients requiring a second dose (25). Roncero and colleagues have shown the effectiveness of lopaxine in managing agitation in the emergency. In their study, inhalation of a single dose of lopaxine (9.1 mg) was enough to calm the acutely agitated patients (29). Prescribing mood stabilizers for managing agitation in BPD patients is highly discouraged by many studies (27, 30). In a report by Clivaz et al., administration of mood stabilizer topiramate augmented the incidences of panic attacks, thus worsening the situation (27). The authors recommended usage of atypical antipsychotics for managing the agitation in BPD patients (27).

In addition to agitation, the patient with BPD may present with a wide array of symptoms that indicate affective dysregulation. Such symptoms may include intense anger, mood liability, intense, depressive moods (31, 32). Administering high doses of antidepressant such as fluoxetine, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor is recommended. However, if it fails, then antidepressants targeting multiple neurotransmitters such as venlafaxine or monoamine oxidase inhibitors should be given. Additionally, BPD patients may also present with the elevated level of anxiety, administration of Clonazepam has shown to be effective in reducing anxiety (31, 32). However, Alprazolam, a drug belonging to the same class as clonazepam, has been reported to aggravate a hostile response.

In patients whose crisis state has subsided by arrival to the ED but who are experiencing severe emotional stress, such as suicidal attempters, psychotherapy is the preferred treatment option (32, 33). In this situation, psychotherapy should be relatively intense for short duration and discontinued before dependence on the therapist develops. Intensive DBT consisting of individual therapy sessions with an emphasis on skills training provided in groups, mindfulness skills, and team consultation for 3 weeks, have been shown to be effective for patients with BPD in crisis, especially with suicidal attempts or gestures (34, 35). Many studies nowadays suggest that after the crisis intervention, these patients should be continued on other form of psychotherapy such as; schematherapy (ST) and mentalization-based treatment (MBT). Because of the effectiveness and validation of MTB by numerous clinical studies, at present, it is widely suggested and included in treatment guidelines of BPD. Moreover, studies have found that intensive outpatient MBT effects are superior to conventional treatment (36, 37). Similarly, ST is a psychotherapy model integrating cognitive, experiential, and behavioral interventions together, which is remarkably effective in decreasing severe symptoms of BPD (38).

Risk Management

Patients with BPD often present with any number of behaviors that are considered disruptive, such as self-harming injuries, violent behavior, impulsivity, or suicide. Such behavioral tendencies put the patient at significant risk to themselves and others if left unmanaged. Thus, the treatment of a patient with BPD should keep risk management in mind, especially as the patient nears the time of discharge. Efficient risk management in emergency settings is required for patients with BPD who exhibit self-injury, violent behavior, suicide, and impulsivity, all of which are considered displays of disruptive behavior (32). To achieve this understanding of the patient’s problem is of prime importance. However, patients and clinicians often have different opinions about the patient’s problem, in an emergency setting, due to the stress and chaos therein (39). Therefore, proper communication is necessary. Boggild et al. and Theinhaus et al. studied the factors responsible for disruptive behaviors in BPD patients. Both the groups found that patients with disruptive behaviors were significantly less likely to report the presence of primary support network, i.e., family members and had more work-related issues than a patient without disruptive behavior (39, 40). In this condition, developing a good rapport by proper communication and discussing their problems and finding alternative solutions should be the attitude of an attending clinicians, social workers, or nurses. Moreover, partial hospitalization has shown to be effective in managing crisis in BPD (41, 42). Nonetheless, the presence of general medical conditions as infectious diseases, psychosocial, and environmental problems such as housing problems, or chronic suicidal ideations are also associated with disruptive behaviors during hospitalization (39). Therefore, addressing the underlying causes of the patient’s disturbance should be approached as plainly such as treating a patient’s infectious disease: understand and address the reason for the suicide attempt and addressing them or finding a solution for temporary stay after discharging from the hospital, which provide comfort to the patients and helping to reduce their disruptive behavior.

Approach Toward BPD Patients

Numerous studies have opined that clinicians and medical staff project a negative attitude for patients with BPD, more so for patients with self-damage or suicidal attitude (43–45). The main reasons for negative attitude include the stigma toward BPD, patients are considered as manipulative, lack of optimism for recovery, work pressure, poor communication skills, and time restraints (43, 46). Among the clinicians in psychiatric department, nurses exhibited negative approach as well as least compassion and hope for the recovery of these patients followed by psychiatrist and psychologist (44, 45, 47). Social workers showed the highest concern, compassion, and treatment optimism for BPD patients. Moreover, general hospital staff display a more adverse attitude toward BPD patients than the employees of psychiatric department (45).

The negative attitude toward BPD patient in crisis makes them more volatile, non-complaint, which makes the diagnosis and treatment difficult leading to problematic outcomes like unnecessary hospitalizations, improper safety assessments, unneeded use of medications, extreme use of physical restraints, and, ultimately, increased liability (44, 45, 47). Imparting proper education through training and workshops separately to different categories of employers in the ED and the general hospital has shown to be effective in building a positive attitude, compassion, and patience toward BPD patients (46, 48, 49). In the crisis, a BPD patient not only comes in contact with emergency medical staff but also with ambulatory staffs as they require ambulance service to arrive emergency (50). Therefore, training of ambulance staff is also required. Treolar et al. (51) assessed the effectiveness of cognitive behavioral treatment and psychoanalytics in changing the attitude toward BPD with self-harm attitude (46). Both treatments showed remarkable improvements in the attitude of clinicians and medical staffs and the effect of psychonalytics was long lasting.

Considering the above studies, applying psychonalytics to different categories of hospital employers starting from ambulance staff to psychiatric and general emergency staff and clinicians for educating them about BPD should be carried out for better management and recovery in these patients.

Treatment

Subsequent to crisis control, proper diagnosis and a treatment regimen should be addressed. The aim of treatment should be to decrease the severity in symptoms such as self-damage, suicidal attempts/gesture, impulsivity, aggressiveness, substance abuse, etc., which in turn will reduce the number of visits to the ED. The treatment for BPD usually lasts for months or years. Psychotherapy along with pharmacotherapy is the usual mode of treatment for BPD (32, 52, 53). Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) are two most extensively studied forms of psychotherapy in BPD patients.

When considering treatment options, physicians should be aware that CBT is an effective and affordable addition to existing care. Davidson et al. assessed the effectiveness of addition of CBT to treatment-as-usual for 1–2 years and reported that adding CBT has only small effect as the number of hospitalization and emergency visits were comparable between both the groups (54). The same group also assessed the long-term effect of the CBT (2–6 years) over treatment-as-usual (55). They observed a decreased in a number of suicidal attempts only. Nevertheless, measures of depression, anxiety, general psychopathology, social functioning, quality of life, dysfunctional attitudes, emergency visits, and mean length of hospitalization were comparable between both the groups. The same group had also utilized a variation of CBT, manual assisted CBT, for treating BPD and concluded that it was unable to reduce the number of attempts for self-damage BPD and was not cost-effective (56).

Linehan et al. conducted an RCT wherein they subjected the BPD with suicidal attempts to DBT for 2 years and observed that it was efficient in reducing the suicide attempt, length of hospitalization for suicide ideation, lowered the medical risk, and decreased psychiatric ED visits (57). Similarly, in adolescents, application of DBT for 52 weeks showed a robust long-term decrease in incidences of self-damage and a fast recovery in suicidal ideation, depression, and borderline symptoms (58, 59). Application of Combined Individual and Group DBT, a variation of DBT, for 12 and 18 months, was found to be equivalent to DBT in reducing the number of suicide attempts, suicidal behavior, and number of emergency visits (60).

Mentalization-based therapy has become a promising psychodynamic approach and added into guidelines for the treatment BPD patients. Mentalizing is related to the capability of interpreting self and others in the form of emotions, feelings, desires, and values. Studies suggest that mentalization impairments are associated with BPD (41). MBT effectively reduces depressive symptoms, suicidal attempts, and self-harm, which also include increasing social functioning in BPD patients (61). As we described earlier in introduction, ST offers an effective help, shows a significant improvement of core symptoms of personality disorder. Reiss et al. summarized the results of three pilot studies investigating the effect of intensive inpatient ST program delivered in individual or group format. Results showed that inpatient ST can significantly reduce symptoms of severe BPD (38). Similarly, other studies have found a large treatment effect in reduction in severity of BPD, impulsivity, affective instability, and general psychopathology (62, 63).

Lana et al. adopted an integrated approach to treat severe BPD patients, which uses multiple psychotherapies in one treatment session (64). It included skill training group based on DBT; relationship therapy supported by MBT; stress management group; and psychoeducational group; individual therapy once a week, support by psychodynamic psychotherapy or DBT depending on the clinician’s approach; medication review; nursing consultation; and telephone consultation for 6 months. Patients with integrated treatment had a lower number of visits to ED and decreased the length of hospitalization during the treatment duration as well as beyond it indicating in efficiency in treating BPD.

A recent systematic review analyzed the competency of psychotherapies in scaling down the suicidal attempts and non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) in borderline patients (65). It concluded that psychotherapy seems to be an effective treatment for suicidal attempts only. For NSSI cases, MBT was a better means of management. This raises a question of the applicability of psychotherapy in BPD patients with other severity symptoms. Hence, a better means of treatment with the broad application is needed. In recent years, functional neuroimaging research describes BPD patients with the dysfunctional frontolimbic network (66). Further, severe BPD patients have impairment in decision-making functionality (67). In view of the above findings, Cailhol et al. evaluated the advantages of intermittent application of high-frequency transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) application on the right cerebral cortex in treating BPD (68).

Transcranial magnetic stimulation remarkably reduced the anger and affective instability in BPD patients after 3 months indicating as a promising technique for managing and treating BPD. As this technique is safe with no side effects and is applied intermittently, its application in acute crisis interventions should also be examined.

Conclusion

Borderline personality disorder patients in crisis are frequent visitors of EDs. Due to lack of knowledge on BPD and social stigma, emergency clinicians and staff develop a negative approach for these patients, which in turn have a negative impact on their treatment outcome. Clinicians and medical staffs should be properly educated about this disorder, which will aid in getting into a comfortable zone with these patients, develop compassion for them and ways for managing the crisis. There is lack of RCTs investigating the efficacy of crisis interventions for people with BPD. Although psychotherapies show a positive effect on reducing BPD-related symptoms, the effect is small. Therefore, we recommend conducting prospective high-quality clinical trials with balanced control groups. These trials should measure a wider range of primary and secondary outcomes of the treatment investigated. All this together will help the patient to get back to the pre-crisis phase and make them more receptive to the actual treatment process.

Author Contributions

SA has provided this idea to write about this important topic, supervised this manuscript, edited its grammar, and added references, written conclusion. US has helped to write manuscript, especially the introduction section. IQ has helped tremendously in this paper, she has worked hard to write two important section of papers including literature search and assisting in finding hand-pick papers from the library. FJ has helped to write a section of crisis intervention, her clinical experience was utilized to finalized that section. SS has helped us to add all studies provided in the table. She also corrected grammar and syntax of the language. YO helped to fix reference, discussion section.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med (2009) 6(7):e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

2. DSM-V, American Psychiatric Association. DSM-V Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association (2013).

4. Paris J, Zweig-Frank H, Guzder J. Psychological risk factors for borderline personality disorder in female patients. Compr Psychiatry (1994) 35(4):301–5. doi:10.1016/0010-440X(94)90023-X

5. Paris J. Childhood trauma as an etiological factor in the personality disorders. J Pers Disord (1997) 11(1):34–49. doi:10.1521/pedi.1997.11.1.34

6. White CN, Gunderson JG, Zanarini MC, Hudson JI. Family studies of borderline personality disorder: a review. Harv Rev Psychiatry (2003) 11(1):8–19. doi:10.1097/00023727-200301000-00002

7. Zanarini MC. Childhood experiences associated with the development of borderline personality disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am (2000) 23(1):89–101. doi:10.1016/S0193-953X(05)70145-3

8. Coid J, Kahtan N, Gault S, Jarman B. Ethnic differences in admissions to secure forensic psychiatry services. Br J Psychiatry (2000) 177:241–7. doi:10.1192/bjp.177.3.241

9. Maden A, Friendship C, McClintock T, Rutter S. Outcome of admission to a medium secure psychiatric unit. 2. Role of ethnic origin. Br J Psychiatry (1999) 175:317–21. doi:10.1192/bjp.175.4.317

10. McGilloway A, Hall RE, Lee T, Bhui KS. A systematic review of personality disorder, race and ethnicity: prevalence, aetiology and treatment. BMC Psychiatry (2010) 10:33. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-10-33

11. Wang L, Ross CA, Zhang T, Dai Y, Zhang H, Tao M, et al. Frequency of borderline personality disorder among psychiatric outpatients in Shanghai. J Pers Disord (2012) 26(3):393–401. doi:10.1521/pedi.2012.26.3.393

12. DSM-IV-TR, American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR). Fourth ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association (2000).

13. Samuels J, Eaton WW, Bienvenu OJ III, Brown CH, Costa PT Jr, Nestadt G. Prevalence and correlates of personality disorders in a community sample. Br J Psychiatry (2002) 180:536–42. doi:10.1192/bjp.180.6.536

14. Torgersen S, Kringlen E, Cramer V. The prevalence of personality disorders in a community sample. Arch Gen Psychiatry (2001) 58(6):590–6. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.58.6.590

15. Gunderson GJ. Boderline personality disoder. N Engl J Med (2011) 364:2037–42. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1007358

16. Biskin RS. The lifetime course of borderline personality disorder. Can J Psychiatry (2015) 60(7):303–8. doi:10.1177/070674371506000702

17. Koehne K, Sands N. Borderline personality disorder—an overview for emergency clinicians. Austr Emerg Nurs J (2008) 11(4):173–7. doi:10.1016/j.aenj.2008.07.003

18. Pascual JC, Córcoles D, Castaño J, Ginés JM, Gurrea A, Martín-Santos R, et al. Hospitalization and pharmacotherapy for borderline personality disorder in a psychiatric emergency service. Psychiatr Serv (2007) 58(9):1199–204. doi:10.1176/ps.2007.58.9.1199

19. Miller FT, Abrams T, Dulit R, Fyer M. Psychotic symptoms in patients with borderline personality disorder and concurrent axis I disorder. Hosp Community Psychiatry (1993) 44(1):59–61.

20. Cailhol L, Damsa C, Bui E, Klein R, Adam E, Schmitt L, et al. [Is assessing for borderline personality disorder useful in the referral after a suicide attempt?]. Encephale (2008) 34(1):23–30. doi:10.1016/j.encep.2007.04.004

21. Johnson AB, Gentile JP, Correll TL. Accurately diagnosing and treating borderline personality disorder: a psychotherapeutic case. Psychiatry (Edgmont) (2010) 7(4):21–30.

22. Borschmann R, Henderson C, Hogg J, Phillips R, Moran P. Crisis interventions for people with borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2012) 6:CD009353. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009353.pub2

23. Nordstrom K, Allen MH. Alternative delivery systems for agents to treat acute agitation: progress to date. Drugs (2013) 73(16):1783–92. doi:10.1007/s40265-013-0130-3

24. Pascual JC, Madre M, Soler J, Barrachina J, Campins MJ, Alvarez E, et al. Injectable atypical antipsychotics for agitation in borderline personality disorder. Pharmacopsychiatry (2006) 39(3):117–8. doi:10.1055/s-2006-941489

25. Damsa C, Adam E, De Gregorio F, Cailhol L, Lejeune J, Lazignac C, et al. Intramuscular olanzapine in patients with borderline personality disorder: an observational study in an emergency room. Gen Hosp Psychiatry (2007) 29(1):51–3. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.10.012

26. Kruger TH, Wollmer MA, Negt P, Frieling H, Jung S, Kahl KG. [Inhaled loxapine for emergency treatment of agitated patients with borderline personality disorder: a series of five cases]. Nervenarzt (2016) 87(11):1222–6. doi:10.1007/s00115-015-0028-2

27. Clivaz E, Chauvet I, Zullino D, Niquille M, Maris S, Cicotti A, et al. Topiramate and panic attacks in patients with borderline personality disorder. Pharmacopsychiatry (2008) 41(2):79. doi:10.1055/s-2007-993214

28. Pascual JC, Oller S, Soler J, Barrachina J, Alvarez E, Pérez V. Ziprasidone in the acute treatment of borderline personality disorder in psychiatric emergency services. J Clin Psychiatry (2004) 65(9):1281–2. doi:10.4088/JCP.v65n0918b

29. Roncero C, Ros-Cucurull E, Grau-López L, Fadeuilhe C, Casas M. Effectiveness of inhaled loxapine in dual-diagnosis patients: a case series. Clin Neuropharmacol (2016) 39(4):206–9. doi:10.1097/WNF.0000000000000153

30. Simpson EB, Yen S, Costello E, Rosen K, Begin A, Pistorello J, et al. Combined dialectical behavior therapy and fluoxetine in the treatment of borderline personality disorder. J Clin Psychiatry (2004) 65(3):379–85. doi:10.4088/JCP.v65n0314

31. Fagin L. Management of personality disorders in acute in-patient settings. Part 1: borderline personality disorders. Adv Psychiatr Treat (2004) 10:93–9. doi:10.1192/apt.10.2.100

32. American Psychiatric Association. Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Borderline Personality Disorder. (2001).

33. Sledge W, Plakun EM, Bauer S, Brodsky B, Caligor E, Clemens NA, et al. Psychotherapy for suicidal patients with borderline personality disorder: an expert consensus review of common factors across five therapies. Borderline Personal Disord Emot Dysregul (2014) 1:16. doi:10.1186/2051-6673-1-16

34. McQuillan A, Nicastro R, Guenot F, Girard M, Lissner C, Ferrero F. Intensive dialectical behavior therapy for outpatients with borderline personality disorder who are in crisis. Psychiatr Serv (2005) 56(2):193–7. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.56.2.193

35. Bernhardt K, Friege L, Gerok-Falke K, Aldenhoff JB. [In-patient treatment concept for acute crises of borderline patients on the basis of dialectical-behavioral therapy]. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol (2005) 55(9–10):397–404. doi:10.1055/s-2005-866884

36. Bateman A, Fonagy P. Randomized controlled trial of outpatient mentalization-based treatment versus structured clinical management for borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry (2009) 166(12):1355–64. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09040539

37. Bateman A, Fonagy P. Mentalization-Based Treatment for Personality Disorder: A Practical Guide. Oxford University Press (2006).

38. Reiss N, Lieb K, Arntz A, Shaw IA, Farrell J. Responding to the treatment challenge of patients with severe BPD: results of three pilot studies of inpatient schema therapy. Behav Cogn Psychother (2014) 42(3):355–67. doi:10.1017/S1352465813000027

39. Thienhaus OJ, Ford J, Hillard JR. Factors related to patients’ decisions to visit the psychiatric emergency service. Psychiatr Serv (1995) 46(12):1227–8. doi:10.1176/ps.46.12.1227

40. Boggild AK, Heisel MJ, Links PS. Social, demographic, and clinical factors related to disruptive behaviour in hospital. Can J Psychiatry (2004) 49(2):114–8. doi:10.1177/070674370404900206

41. Bateman A, Fonagy P. Effectiveness of partial hospitalization in the treatment of borderline personality disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry (1999) 156(10):1563–9. doi:10.1176/ajp.156.10.1563

42. Paris J. Is hospitalization useful for suicidal patients with borderline personality disorder? J Pers Disord (2004) 18(3):240–7. doi:10.1521/pedi.18.3.240.35443

43. Weight EJ, Kendal S. Staff attitudes towards inpatients with borderline personality disorder. Mental Health Pract (2013) 17(3):34–8. doi:10.7748/mhp2013.11.17.3.34.e827

44. Bodner E, Cohen-Fridel S, Mashiah M, Segal M, Grinshpoon A, Fischel T, et al. The attitudes of psychiatric hospital staff toward hospitalization and treatment of patients with borderline personality disorder. BMC Psychiatry (2015) 15:2. doi:10.1186/s12888-014-0380-y

45. Kate EA, Saunders KH, Fortune S, Farrell S. Attitudes and knowledge of clinical staff regarding people who self-harm: a systematic review. J Affect Disord (2012) 139:205–16. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2011.08.024

46. Treloar AJC. A qualitative investigation of the clinician experience of working with borderline personality disorder. NZ J Psychol (2009) 38(2):30–4.

47. Black DW, Pfohl B, Blum N, McCormick B, Allen J, North CS, et al. Attitudes toward borderline personality disorder: a survey of 706 mental health clinicians. CNS Spectr (2011) 16(3):67–74. doi:10.1017/S109285291200020X

48. Commons Treloar AJ, Lewis AJ. Targeted clinical education for staff attitudes towards deliberate self-harm in borderline personality disorder: randomized controlled trial. Aust N Z J Psychiatry (2008) 42(11):981–8. doi:10.1080/00048670802119796

49. Commons Treloar AJ, Lewis AJ. Professional attitudes towards deliberate self-harm in patients with borderline personality disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry (2008) 42(7):578–84. doi:10.1080/00048670802119796

50. Jamieson L. A brief guide to borderline personality disorder for pre-hospital clinicians in an emergency setting. J Paramed Pract (2015) 7(8):386–92. doi:10.12968/jpar.2015.7.8.386

51. Treloar AJ. Effectiveness of education programs in changing clinicians’ attitudes toward treating borderline personality disorder. Psychiatr Serv (2009) 60(8):1128–31. doi:10.1176/ps.2009.60.8.1128

52. Oldham JM. Borderline personality disorder and suicidality. Am J Psychiatry (2006) 163(1):20–6. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.20

53. Lieb K, Völlm B, Rücker G, Timmer A, Stoffers JM. Pharmacotherapy for borderline personality disorder: cochrane systematic review of randomised trials. Br J Psychiatry (2010) 196(1):4–12. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.108.062984

54. Davidson K, Norrie J, Tyrer P, Gumley A, Tata P, Murray H, et al. The effectiveness of cognitive behavior therapy for borderline personality disorder: results from the borderline personality disorder study of cognitive therapy (BOSCOT) trial. J Pers Disord (2006) 20(5):450–65. doi:10.1521/pedi.2006.20.5.450

55. Davidson KM, Tyrer P, Norrie J, Palmer SJ, Tyrer H. Cognitive therapy v. usual treatment for borderline personality disorder: prospective 6-year follow-up. Br J Psychiatry (2010) 197(6):456–62. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.109.074286

56. Davidson K, Scott J, Schmidt U, Tata P, Thornton S, Tyrer P. Therapist competence and clinical outcome in the Prevention of Parasuicide by Manual Assisted Cognitive Behaviour Therapy trial: the POPMACT study. Psychol Med (2004) 34(5):855–63. doi:10.1017/S0033291703001855

57. Linehan MM, Comtois KA, Murray AM, Brown MZ, Gallop RJ, Heard HL, et al. Two-year randomized controlled trial and follow-up of dialectical behavior therapy vs therapy by experts for suicidal behaviors and borderline personality disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry (2006) 63(7):757–66. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.757

58. Mehlum L, Ramberg M, Tørmoen AJ, Haga E, Diep LM, Stanley BH, et al. Dialectical behavior therapy compared with enhanced usual care for adolescents with repeated suicidal and self-harming behavior: outcomes over a one-year follow-up. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry (2016) 55(4):295–300. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2016.01.005

59. Mehlum L, Tørmoen AJ, Ramberg M, Haga E, Diep LM, Laberg S, et al. Dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents with repeated suicidal and self-harming behavior: a randomized trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry (2014) 53(10):1082–91. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2014.07.003

60. Andion O, Ferrer M, Matali J, Gancedo B, Calvo N, Barral C, et al. Effectiveness of combined individual and group dialectical behavior therapy compared to only individual dialectical behavior therapy: a preliminary study. Psychotherapy (Chic) (2012) 49(2):241–50. doi:10.1037/a0027401

61. Choi-Kain LW, Gunderson JG. Mentalization: ontogeny, assessment, and application in the treatment of borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry (2008) 165(9):1127–35. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07081360

62. Farrell JM, Shaw IA, Webber MA. A schema-focused approach to group psychotherapy for outpatients with borderline personality disorder: a randomized controlled trial. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry (2009) 40(2):317–28. doi:10.1016/j.jbtep.2009.01.002

63. Stoffers JM, Völlm BA, Rücker G, Timmer A, Huband N, Lieb K. Psychological therapies for people with borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2012) (8):CD005652. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005652.pub2

64. Lana F, Sanchez-Gil C, Perez V, Martí-Bonany J. A stepped care approach to psychotherapy in borderline personality disorder. Ann Clin Psychiatry (2016) 28(2):140–1.

65. Calati R, Courtet P. Is psychotherapy effective for reducing suicide attempt and non-suicidal self-injury rates? Meta-analysis and meta-regression of literature data. J Psychiatr Res (2016) 79:8–20. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.04.003

66. Leichsenring F, Leibing E, Kruse J, New AS, Leweke F. Borderline personality disorder. Lancet (2011) 377(9759):74–84. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61422-5

67. Svaldi J, Philipsen A, Matthies S. Risky decision-making in borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Res (2012) 197(1–2):112–8. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2012.01.014

68. Cailhol L, Roussignol B, Klein R, Bousquet B, Simonetta-Moreau M, Schmitt L, et al. Borderline personality disorder and rTMS: a pilot trial. Psychiatry Res (2014) 216(1):155–7. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2014.01.030

69. Philipsen A, Schmahl C, Lieb K. Naloxone in the treatment of acute dissociative states in female patients with borderline personality disorder. Pharmacopsychiatry (2004) 37(5):196–9. doi:10.1055/s-2004-827243

70. Damsa C, Andreoli A, Zullino D, Adam E, Mihai A, Maris S, et al. Quality of care in emergency psychiatry: developing an international network. Eur Psychiatry (2007) 22(6):411–2. doi:10.1016/S0924-9338(06)90120-5

71. Linehan MM, McDavid JD, Brown MZ, Sayrs JH, Gallop RJ. Olanzapine plus dialectical behavior therapy for women with high irritability who meet criteria for borderline personality disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. J Clin Psychiatry (2008) 69(6):999–1005. doi:10.4088/JCP.v69n0617

72. Berrino A, Ohlendorf P, Duriaux S, Burnand Y, Lorillard S, Andreoli A. Crisis intervention at the general hospital: an appropriate treatment choice for acutely suicidal borderline patients. Psychiatry Res (2011) 186(2–3):287–92. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2010.06.018

73. Bertsch K, Gamer M, Schmidt B, Schmidinger I, Walther S, Kästel T, et al. Oxytocin and reduction of social threat hypersensitivity in women with borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry (2013) 170(10):1169–77. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13020263

74. Carvalho Fernando S, Beblo T, Schlosser N, Terfehr K, Wolf OT, Otte C, et al. Acute glucocorticoid effects on response inhibition in borderline personality disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology (2013) 38(11):2780–8. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.07.008

75. Brune M. On the role of oxytocin in borderline personality disorder. Br J Clin Psychol (2016) 55(3):287–304. doi:10.1111/bjc.12100

76. Hollander E, Dolgoff-Kaspar R, Cartwright C, Rawitt R, Novotny S. An open trial of divalproex sodium in autism spectrum disorders. J Clin Psychiatry (2001) 62(7):530–4. doi:10.4088/JCP.v62n07a05

77. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR. Olanzapine treatment of female borderline personality disorder patients: a double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. J Clin Psychiatry (2001) 62(11):849–54. doi:10.4088/JCP.v62n1103

78. Rinne T, van den Brink W, Wouters L, van Dyck R. SSRI treatment of borderline personality disorder: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial for female patients with borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry (2002) 159(12):2048–54. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.159.12.2048

79. Rocca P, Marchiaro L, Cocuzza E, Bogetto F. Treatment of borderline personality disorder with risperidone. J Clin Psychiatry (2002) 63(3):241–4. doi:10.4088/JCP.v63n0311

80. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Parachini EA. A preliminary, randomized trial of fluoxetine, olanzapine, and the olanzapine-fluoxetine combination in women with borderline personality disorder. J Clin Psychiatry (2004) 65(7):903–7. doi:10.4088/JCP.v65n0704

81. Bogenschutz MP, George Nurnberg H. Olanzapine versus placebo in the treatment of borderline personality disorder. J Clin Psychiatry (2004) 65(1):104–9. doi:10.4088/JCP.v65n0118

82. Villeneuve E, Lemelin S. Open-label study of atypical neuroleptic quetiapine for treatment of borderline personality disorder: impulsivity as main target. J Clin Psychiatry (2005) 66(10):1298–303. doi:10.4088/JCP.v66n1013

83. Bellino S, Paradiso E, Bogetto F. Oxcarbazepine in the treatment of borderline personality disorder: a pilot study. J Clin Psychiatry (2005) 66(9):1111–5. doi:10.4088/JCP.v66n0904

84. Soler J, Pascual JC, Campins J, Barrachina J, Puigdemont D, Alvarez E, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled study of dialectical behavior therapy plus olanzapine for borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry (2005) 162(6):1221–4. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1221

85. Hollander E, Soorya L, Wasserman S, Esposito K, Chaplin W, Anagnostou E. Divalproex sodium vs. placebo in the treatment of repetitive behaviours in autism spectrum disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol (2006) 9(2):209–13. doi:10.1017/S1461145705005791

86. Tritt K, Nickel C, Lahmann C, Leiberich PK, Rother WK, Loew TH, et al. Lamotrigine treatment of aggression in female borderline-patients: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Psychopharmacol (2005) 19(3):287–91. doi:10.1177/0269881105051540

87. Loew TH, Nickel MK, Muehlbacher M, Kaplan P, Nickel C, Kettler C, et al. Topiramate treatment for women with borderline personality disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychopharmacol (2006) 26(1):61–6. doi:10.1097/01.jcp.0000195113.61291.48

88. Nickel MK, Nickel C, Mitterlehner FO, Tritt K, Lahmann C, Leiberich PK, et al. Topiramate treatment of aggression in female borderline personality disorder patients: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry (2004) 65(11):1515–19.

89. Giesen-Bloo J, van Dyck R, Spinhoven P, van Tilburg W, Dirksen C, van Asselt T, et al. Outpatient psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder: randomized trial of schema-focused therapy vs transference-focused psychotherapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry (2006) 63(6):649–58. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.63.6.649

90. Nickel MK, Muehlbacher M, Nickel C, Kettler C, Pedrosa Gil F, Bachler E, et al. Aripiprazole in the treatment of patients with borderline personality disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry (2006) 163(5):833–8. doi:10.1176/ajp.2006.163.5.833

91. Bellino S, Paradiso E, Bogetto F. Efficacy and tolerability of quetiapine in the treatment of borderline personality disorder: a pilot study. J Clin Psychiatry (2006) 67(7):1042–6. doi:10.4088/JCP.v67n0705

92. Clarkin JF, Levy KN, Lenzenweger MF, Kernberg OF. Evaluating three treatments for borderline personality disorder: a multiwave study. Am J Psychiatry (2007) 164(6):922–8. doi:10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.922

93. Silva H, Iturra P, Solari A, Villarroel J, Jerez S, Vielma W, et al. Serotonin transporter polymorphism and fluoxetine effect on impulsiveness and aggression in borderline personality disorder. Actas Esp Psiquiatr (2007) 35(6):387–92.

94. Bateman A, Fonagy P. 8-year follow-up of patients treated for borderline personality disorder: mentalization-based treatment versus treatment as usual. Am J Psychiatry (2008) 165(5):631–8. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07040636

95. Adityanjee, Romine A, Brown E, Thuras P, Lee S, Schulz SC. Quetiapine in patients with borderline personality disorder: an open-label trial. Ann Clin Psychiatry (2008) 20(4):219–26. doi:10.1080/10401230802467545

96. Blum N, St John D, Pfohl B, Stuart S, McCormick B, Allen J, et al. Systems Training for Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving (STEPPS) for outpatients with borderline personality disorder: a randomized controlled trial and 1-year follow-up. Am J Psychiatry (2008) 165(4):468–78. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07071079

97. Pascual JC, Soler J, Puigdemont D, Pérez-Egea R, Tiana T, Alvarez E, et al. Ziprasidone in the treatment of borderline personality disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized study. J Clin Psychiatry (2008) 69(4):603–8. doi:10.4088/JCP.v69n0412

98. Van den Eynde F, Senturk V, Naudts K, Vogels C, Bernagie K, Thas O, et al. Efficacy of quetiapine for impulsivity and affective symptoms in borderline personality disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol (2008) 28(2):147–55. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e318166c4bf

99. Bellino S, Paradiso E, Bogetto F. Efficacy and tolerability of aripiprazole augmentation in sertraline-resistant patients with borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Res (2008) 161(2):206–12. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2007.07.006

100. McMain SF, Links PS, Gnam WH, Guimond T, Cardish RJ, Korman L, et al. A randomized trial of dialectical behavior therapy versus general psychiatric management for borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry (2009) 166(12):1365–74. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09010039

101. Reich DB, Zanarini MC, Bieri KA. A preliminary study of lamotrigine in the treatment of affective instability in borderline personality disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol (2009) 24(5):270–5. doi:10.1097/YIC.0b013e32832d6c2f

102. Ziegenhorn AA, Roepke S, Schommer NC, Merkl A, Danker-Hopfe H, Perschel FH, et al. Clonidine improves hyperarousal in borderline personality disorder with or without comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol (2009) 29(2):170–3. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e31819a4bae

103. Shafti SS, Shahveisi B. Olanzapine versus haloperidol in the management of borderline personality disorder: a randomized double-blind trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol (2010) 30(1):44–7. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181c826ff

104. Bellino S, Paradiso E, Bozzatello P, Bogetto F. Efficacy and tolerability of duloxetine in the treatment of patients with borderline personality disorder: a pilot study. J Psychopharmacol (2010) 24(3):333–9. doi:10.1177/0269881108095715

105. Doering S, Hörz S, Rentrop M, Fischer-Kern M, Schuster P, Benecke C, et al. Transference-focused psychotherapy v. treatment by community psychotherapists for borderline personality disorder: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry (2010) 196(5):389–95. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.109.070177

106. Harned MS, Jackson SC, Comtois KA, Linehan MM. Dialectical behavior therapy as a precursor to PTSD treatment for suicidal and/or self-injuring women with borderline personality disorder. J Trauma Stress (2010) 23(4):421–9. doi:10.1002/jts.20553

107. Zanarini MC, Schulz SC, Detke HC, Tanaka Y, Zhao F, Lin D, et al. A dose comparison of olanzapine for the treatment of borderline personality disorder: a 12-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry (2011) 72(10):1353–62. doi:10.4088/JCP.08m04138yel

108. Zanarini MC, Schulz SC, Detke H, Zhao F, Lin D, Pritchard M, et al. Open-label treatment with olanzapine for patients with borderline personality disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol (2012) 32(3):398–402. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e3182524293

109. Moen R, Freitag M, Miller M, Lee S, Romine A, Song S, et al. Efficacy of extended-release divalproex combined with “condensed” dialectical behavior therapy for individuals with borderline personality disorder. Ann Clin Psychiatry (2012) 24(4):255–60.

110. Schmahl C, Kleindienst N, Limberger M, Ludäscher P, Mauchnik J, Deibler P, et al. Evaluation of naltrexone for dissociative symptoms in borderline personality disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol (2012) 27(1):61–8. doi:10.1097/YIC.0b013e32834d0e50

111. Carrasco JL, Palomares N, Marsa MD. Effectiveness and tolerability of long-acting intramuscular risperidone as adjuvant treatment in refractory borderline personality disorder. Psychopharmacology (Berl) (2012) 224(2):347–8. doi:10.1007/s00213-012-2880-0

112. Kröger C, Harbeck S, Armbrust M, Kliem S. Effectiveness, response, and dropout of dialectical behavior therapy for borderline personality disorder in an inpatient setting. Behav Res Ther (2013) 51(8):411–6. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2013.04.008

113. Jørgensen CR, Freund C, Bøye R, Jordet H, Andersen D, Kjølbye M. Outcome of mentalization-based and supportive psychotherapy in patients with borderline personality disorder: a randomized trial. Acta Psychiatr Scand (2013) 127(4):305–17. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2012.01923.x

114. Reneses B, Galián M, Serrano R, Figuera D, Fernandez Del Moral A, López-Ibor JJ, et al. A new time limited psychotherapy for BPD: preliminary results of a randomized and controlled trial. Actas Esp Psiquiatr (2013) 41(3):139–48.

115. Gratz KL, Tull MT, Levy R. Randomized controlled trial and uncontrolled 9-month follow-up of an adjunctive emotion regulation group therapy for deliberate self-harm among women with borderline personality disorder. Psychol Med (2014) 44(10):2099–112. doi:10.1017/S0033291713002134

116. Black DW, Zanarini MC, Romine A, Shaw M, Allen J, Schulz SC. Comparison of low and moderate dosages of extended-release quetiapine in borderline personality disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry (2014) 171(11):1174–82. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13101348

117. Harned MS, Korslund KE, Linehan MM. A pilot randomized controlled trial of dialectical behavior therapy with and without the dialectical behavior therapy prolonged exposure protocol for suicidal and self-injuring women with borderline personality disorder and PTSD. Behav Res Ther (2014) 55:7–17. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2014.01.008

118. Linehan MM, Korslund KE, Harned MS, Gallop RJ, Lungu A, Neacsiu AD, et al. Dialectical behavior therapy for high suicide risk in individuals with borderline personality disorder: a randomized clinical trial and component analysis. JAMA Psychiatry (2015) 72(5):475–82. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.3039

119. Leichsenring F, Masuhr O, Jaeger U, Rabung S, Dally A, Dümpelmann M, et al. Psychoanalytic-interactional therapy versus psychodynamic therapy by experts for personality disorders: a randomized controlled efficacy-effectiveness study in cluster B personality disorders. Psychother Psychosom (2016) 85(2):71–80. doi:10.1159/000441731

Keywords: borderline personality disorder, emergency psychiatry, psychotherapy, cluster B personality disorders, psychosocial issues, impulsivity, aggression, suicidality

Citation: Shaikh U, Qamar I, Jafry F, Hassan M, Shagufta S, Odhejo YI and Ahmed S (2017) Patients with Borderline Personality Disorder in Emergency Departments. Front. Psychiatry 8:136. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00136

Received: 27 March 2017; Accepted: 13 July 2017;

Published: 04 August 2017

Edited by:

Bahar Güntekin, Istanbul Medipol University, TurkeyReviewed by:

Adonis Sfera, Loma Linda University, United StatesMichiel F. van Vreeswijk, G-kracht Mental Health Care Institute, Netherlands

Copyright: © 2017 Shaikh, Qamar, Jafry, Hassan, Shagufta, Odhejo and Ahmed. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Saeed Ahmed, ahmedsaeedmd@gmail.com

Untara Shaikh

Untara Shaikh Iqra Qamar

Iqra Qamar Farhana Jafry

Farhana Jafry Mudasar Hassan

Mudasar Hassan Shanila Shagufta

Shanila Shagufta Yassar Islamail Odhejo1

Yassar Islamail Odhejo1 Saeed Ahmed

Saeed Ahmed