- 1Cognition and Human Behavior Key Laboratory of Hunan and Department of Psychology, Hunan Normal University, Changsha, China

- 2Department of Psychology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, Hong Kong

Gratitude has been investigated in various areas in psychology. The present research showed that gratitude had some positive effects on some aspects of our life, such as subjective well-being, life satisfaction, and social relationships. It can also help us relieve negative emotions. However, the existing literature has not studied the influence of gratitude on envy. The present study used structural equation modeling to test the mediating role of social support between gratitude and two types of envy (malicious and benign). We recruited 426 Chinese undergraduates to complete the Gratitude Questionnaire, Malicious and Benign Envy Scales, and the Multi-Dimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. Results showed that gratitude positively predicted benign envy and negatively predicted malicious envy. In addition, the indirect effect of gratitude on two types of envy via social support was significant. These results revealed the direct relationship between gratitude and malicious/benign envy, and the mediating effect of social support, which will contribute to find effective measures to inhibit malicious envy and promote benign envy from the perspective of cultivating gratitude and increasing individuals' social support.

Introduction

Gratitude, a kind of positive emotion, has drawn much attention from various psychological perspectives, including personality, social emotion, and clinical psychology (1, 2). Gratitude can be defined as a complex subjective feeling including wonder, thankfulness, and even appreciation in one's life (3, 4), which is a kind of positive energy and has a broad effect in our lives. For example, studies have suggested that gratitude could affect individual subjective well-being and life satisfaction (5–7), strengthen social relationships (8), and elicit prosocial behavior (9–11). At the same time, gratitude could also inhibit negative emotions. For example, researchers have demonstrated that higher levels of gratitude could lead to lower levels of stress or depression (12). Another study also suggested that higher levels of gratitude corresponded with lower levels of envy (13). These studies suggest that gratitude may not only related to positive emotions, but also related to negative emotions such as anxiety, depression, and envy. However, it is important to know how to reduce negative feelings as well as how to enhance positive feeling. The present study focuses on exploring how gratitude affects envy. Until now, there has been no further research exploring how gratitude affects envy, let alone how gratitude affects two quite different types of envy, benign and malicious envy. In the present study, we explore the relationship between gratitude and two types of envy (benign and malicious) and how social support mediates such relationships.

Indeed, some studies have explored the relationship between gratitude and dispositional envy. For example, gratitude was found to have significant negative correlation with dispositional envy (2, 13, 14). The reason may be attributed to the different emotional components between two emotions. Dispositional envy, as a kind of complex negative emotion characterized by resentment, inferiority, longing, and frustration, arises when the self realizes it lacks another's superior quality, achievement, or possessions (15–17). In contrast to envy, gratitude is a complex positive emotion including wonder, thankfulness, appreciation, and so on (3, 4), which is probably incompatible with envy (13, 14). McCullough et al. (13) further demonstrated that grateful people did not focus on acquiring and maintaining possessions and wealth; instead, and they focused on savoring positive experiences and outcomes. Contrary to gratitude, envious people tend to focus on acquiring others' possessions. There is no doubt that people with gratitude would focus on positive contributions of others to their well-being in social comparison rather than to get others' possessions. Therefore, gratitude may have negative correlation with envy.

The rationale under the relationship between gratitude and envy is clear from the above literature. However, in recent years, envy have been classified as explicitly malicious and benign (16–18). Therefore, it is necessary to further explore the relationship between gratitude and the two types of envy. The classification of two types of envy is based on the cognition and motivation function of envy. For example, benign envy elicits individual self-elevating motivation, while malicious envy leads to the tendency of slander or revenge against others (19). Crusius and Lange (20) further demonstrated that benign envy had significant positive correlation with motivation of hope for success, and malicious envy had significant positive correlation with motivation of fear of failure. Although McCullough et al. (2, 13) demonstrated the significant negative correlation between gratitude and dispositional envy, the questionnaire they used on dispositional envy was adopted from Smith et al.'s study (21). Some researchers pointed out that the Dispositional Envy Scale (DES) may represent largely malicious envy, rather than benign envy (17). Therefore, we suggest that gratitude can significantly and negatively predict malicious envy, but this is not true for benign envy. According to condition-elicited benign envy, benign envy is often elicited if one person's advantage is evaluated as subjectively deserved and if the envier perceives high control over personal outcomes (19). If one person tends to have higher levels of benign envy, that person also tends to focus on the positive aspect of the advantages the envied person had over him or her in the context of social comparison. This characteristic is consistent with dispositional gratitude, as described by McCullough et al. (13). Therefore, we hypothesize that gratitude will significantly and positively predict benign envy.

In addition, previous studies indicated that gratitude was closely related to prosocial behavior (9–11, 22). For example, Fredrickson (23) pointed out that gratitude could reflect, motivate, and reinforce social actions in both givers and gift recipients. Therefore, people with higher levels of gratitude may also obtain more social resources, especially social support from others. Some empirical studies have further supported this hypothesis. For example, people with higher levels of gratitude are found to be more likely to perceive and receive greater social support from others, including family, friends, or even strangers (12, 24). Therefore, we hypothesize that gratitude may also positively and significantly predict social support. Regarding social support, it has been identified one of the most promising mediator between gratitude and life satisfaction, which is closely related to mental health (7). Previous studies have also directly demonstrated that social support has a close connection to mental health (25). Specifically, individuals with higher levels of social support may have better mental health. On the contrary, those with lower levels of social support may show more negative emotions, such as depression, anxiety, and hostility, and even express more aggressive behavior (26, 27). However, the presence or absence of hostility is the key characteristic to distinguish between the two types of envy. Smith and Kim (27) suggested that malicious envy is a hostile emotion and has hostile nature. As we mentioned before, envious people typically report depressive, unhappy feelings (21), also hostility. These negative emotional states appear to affect mental health (28–30). It is possible that people with higher level envy doesn't receive and feel the benefits of social support because of their hostile attitudes and behaviors. (31–33). Actually, evidence showed that envy with hostility (malicious envy) was significantly negatively related to social support (32, 33). The reason is that lower social support may mean more hostility or more sensitivity during social interaction or comparison, it is easy for these individuals to experience malicious envy. Similarly, we speculate that higher levels of social support may lead to less hostility in social comparison, which may result in higher levels of benign envy. According to the above analyses, we hypothesize that social support may play a mediating role between gratitude and the two types of envy.

Thus, the present study focuses on exploring the relationship between gratitude and benign/malicious envy as well as the mediating role of social support. Based on the review literature above, we propose the following hypotheses: (1) Gratitude can significantly and positively predict benign envy and negatively predict malicious envy. (2) Social support can positively predict benign envy and negatively predict malicious envy. (3) Social support plays a positive mediating role in the relationship between gratitude and benign envy and a negative mediating role in the relationship between gratitude and malicious envy.

Materials and Methods

Participants and Procedure

Four hundred twenty-six Chinese undergraduates from South China Normal University and Jinan University were recruited randomly. The basic demographic characteristics were shown as follows: 142 men, 284 women; mean age = 20.63 ± 1.85; age range = 18–26 years. The present study was approved by the Academic Committee of the School of Psychology at South China Normal University. All participants were provided with written informed consent before the study and were allowed to leave whenever they felt uncomfortable. It took around 40 min for every participant to finish the following tests.

Measures

Gratitude

This variable was measured by the Gratitude Questionnaire (GQ-6, (13)). This scale includes 6 items with each item rated on a 7-point Likert scale. Higher scores indicate higher levels of gratitude. Many studies have indicated that the Chinese version of the GQ-6 is a reliable and valid measurement (7, 34). Cronbach's alpha coefficient was 0.81 in the present study.

Malicious and Benign Envy

The two scales were developed by Lange and Crusius (17). Each scale consists of 5 items, each scored on a 6-point Likert scale. In this study, the malicious and benign envy scales showed adequate internal reliability (the former Cronbach's alpha was 0.85, the latter was 0.73).

Multi-Dimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MPSS)

This scale was developed by Zimet et al. (35). There are 12 items scored on a 7-point Likert scale. This scale consists of three subscales: family's support, friends' support, and others' support. This scale has been used widely among Chinese people (36–38). In the present study, Cronbach's alpha coefficient for the MPSS was 0.90.

Data Analysis

To test whether the indicators represent the latent variables, a measurement model was tested at the beginning in AMOS 17.0. In addition, we also divided the items for gratitude and benign and malicious envy in the MPSS into two or three parcels to serve as indicators of the factors using an item-to-construct balance approach (39). To judge the model's goodness of fit, we chose the Chi square statistic, standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR), root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), and comparative fit index (CFI) as the indicators (40). In addition, we used the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) to judge which model demonstrated better fit (41). The expected cross-validation index (ECVI) was used to evaluate potential for replication (42).

Results

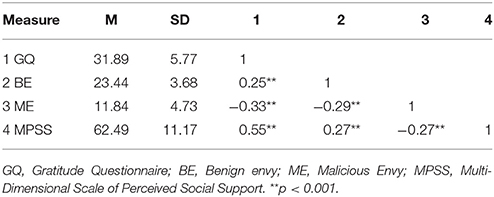

Measurement Model

Latent variables in the measurement model included gratitude, benign envy, malicious envy, and MPSS. Results showed that the data fit well into the measurement model [χ2(21, N = 426) = 15.245, P = 0.002; RMSEA = 0.052; SRMR = 0.0373; CFI = 0.984]. In addition, factor loadings of all the latent variables were significantly correlated (P < 0.001), which suggested that latent variables well represented the observed variables. Moreover, all latent variables were significantly related. Means, standard deviations, and correlations between gratitude, benign envy, malicious envy, and social support are shown in Table 1.

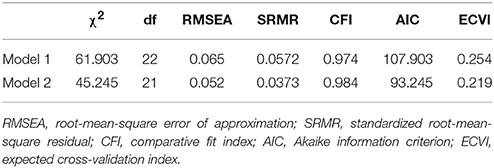

Structural Model

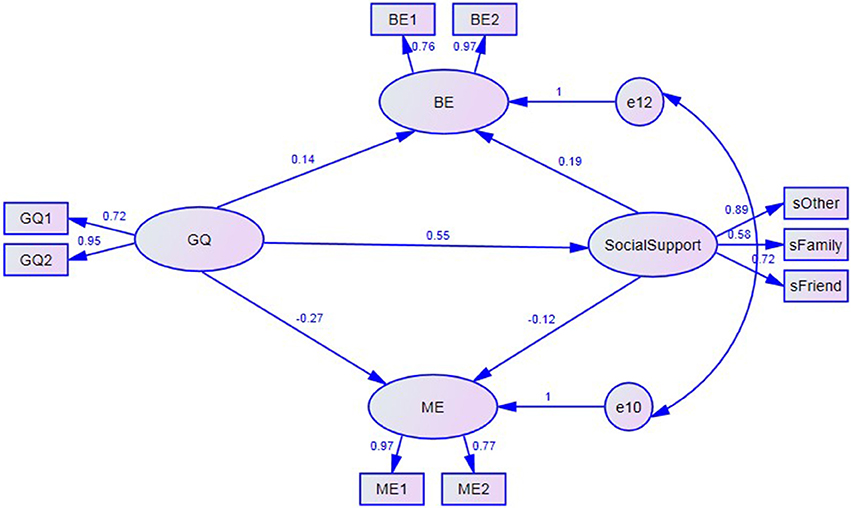

When lacking the mediator (social support), gratitude (predictor) could significantly predict benign (β = 0.20, P < 0.01) and malicious envy (β = −0.28, P < 0.001) (criterion), respectively. We then set Model 1, in which gratitude directly predicted benign and malicious envy while also indirectly predicting those two variables through social support. Results showed that all indices except RMSEA were good indices (Table 2) [ = 61.903, P < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.065; SRMR = 0.0572; and CFI = 0.974]. Further, we found that benign envy and the error terms of malicious envy were admissibly correlated. Thus, we constructed Model 2 based on Model 1. Results showed that this model had significantly good fit for the observed variables [ = 45.245, P < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.052; SRMR = 0.0373; and CFI = 0.984]. Compared with Model 1, we found that Model 2 had a much smaller [Δχ2 (1, N = 426) = 16.657, P < 0.001] and a smaller AIC, suggesting that Model 2 has a better fit than Model 1. Thus, we used Model 2 as the final testing model (See Figure 1).

Figure 1. The mediation model. Factor loadings are standardized. BE1 and BE2 are two parcels of benign envy; ME1 and ME2 are two parcels of malicious envy; GQ1 and GQ2 are two parcels gratitude; sOther, sFamily and sFriend are subscales of the Multi-Dimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support.

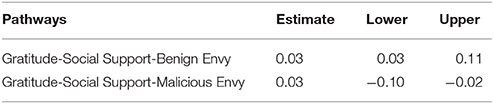

Further, we used a bootstrap estimation procedure to investigate the robustness of this mediation effect. Results indicated that a 95% confidence interval was significantly correlated to the mediation effect. As we can see in Table 3, gratitude significantly and indirectly influenced benign (95% confidence intervals [0.03~0.11]) and malicious envy (95% confidence intervals [−0.10~−0.02]) through the mediating variable social support.

Gender Difference

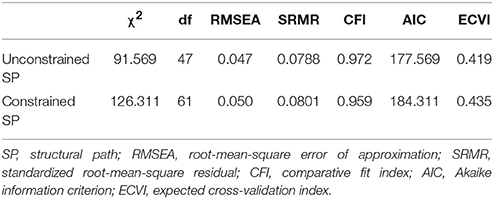

We used four latent variables to test for difference between genders. Results showed that there was no significant gender difference in malicious envy [t(424) = −0.076, P = 0.939] and gratitude [t(424) = −1.391, P = 0.165]. However, we found significant gender differences in social support [t(424) = −2.437, P = 0.015] and benign envy [t(424) = −2.117, P = 0.035], in both of which female participants scored higher than male participants. Based on this, we further explored the robustness of gender differences in the structural equation model that we found.

We used a multi-group analysis to investigate the path coefficients in the model of gender differences. Based on keeping the basic parameters (factor loadings, error variances, and structure covariances) stable, we constructed two models. One allowed for free estimations of paths across genders in the two models while the other limited the paths equaled in two models. Results showed significant differences in [ = 35.303, P < 0.001]; however, the two models reached the standard of fitness when we compared other parameters in the two models (see Table 4). Thus, in general, deformable models of parameter limitations in multiple groups are acceptable. In addition, we used critical ratio of differences (CRD) as an indicator in investigating the difference between the standard errors of two sexes. According to the decision rule, CRD > 1.96 means the two parameters are significantly different at a significant level of P < 0.05. The results showed that the structural path from GQ to social support had significant difference (CRD = 2.467, P < 0.05). Specifically, the path coefficient in male participants was β = 0.635 (P < 0.001) while the path coefficient in female participants was β = 0.445 (P < 0.001). This result indicates the positive effect of gratitude in social support is significantly greater in male than in female participants.

Discussion

The present study aimed to test the relationship between gratitude and benign/malicious envy and the mediating role of social support. The result revealed that gratitude could predict benign envy positively and malicious envy negatively. Furthermore, the indirect effect of gratitude on the two types of envy via social support was significant. These results first directly revealed the relationship between gratitude and two different kinds of envy and the mediating effect of social support, which contributed to effective measures to inhibit malicious envy and promote benign envy from the perspective of cultivating gratitude and increasing individuals' social support.

According to the result of a correlation analysis, gratitude had significant and negative correlation with malicious envy, which was also confirmed by the regression coefficient in the structure model. This result is consistent with the results of previous studies (13, 14), which also found this negative relationship between gratitude and envy with hostile emotion. On the other hand, consistent with our hypothesis, we also found that gratitude was related significantly and positively to benign envy, which was in accordance with the regression coefficient in the structure model. Two opposite results indicated that the relationship between gratitude and envy, which has been demonstrated by previous studies, should be distinguished according to different types of envy. In particular, higher levels of gratitude indicated lower levels of malicious envy and higher levels of benign envy. This can be explained by McCullough et al. (2, 13)—that is, gratitude leads individuals to focus on positive contribution of the envied person in social comparison; therefore, they tend to show lower malicious envy and higher benign envy.

Moreover, in line with our hypothesis, we found gratitude was positively related to social support, which was also consistent with several empirical. Previous studies indicated that gratitude was significantly and positively correlated with social support (7, 12, 43). In addition, we also found that social support was positively related to benign envy and negatively to malicious envy. The former result was consistent with previous studies (32, 33), and the latter supported our previous hypothesis—that is, higher social support may inhibit the hostility of malicious envy, resulting in lower levels of malicious envy. In addition, previous studies also explored the relationship between social support and social pain or perceived control. Some studies found that social support benefited coping with social stress and relieving social pain (44, 45), and many others also demonstrated that higher social support can improve the feeling of perceiving control (46, 47). According to previous studies, control potential was a key factor to distinguish between two kinds of envy; greater control perception tended to be elicited by benign envy, and reduced control perception tended to be elicited by malicious envy (48). Therefore, higher social support may improve the feeling of self controllability in facing stress because of social comparison and then promote benign envy and inhibit malicious envy.

Based on the analyses above, we can also further explain the mediating effect of social support in the final model. There existed two partial mediating relationships as follows: gratitude → social support → benign envy, gratitude → social support → malicious envy. Combined with the direction of the correlation coefficient, we can conclude that grateful people tend to have high levels of social support from others, and, furthermore, higher levels of social support will lead to higher levels of benign envy and lower levels of malicious envy. Social support plays a positive role in the interaction between gratitude and benign envy but plays an inhibitory role in the relationship between gratitude and malicious envy. Whatever promotes benign envy or inhibits malicious envy, the key factor depends on whether higher social support can effectively relieve social pain or strengthen the feeling of self-control. One encouraging thing about this result is, we found social support plays a rather critical role here, which is consistent with previous studies that social support is closely related to mental health (25, 26). And this is a quite practical way to improve both gratitude and benign envy, as well as reducing malicious envy. This provides preliminary evidence for future studies using social support as an intervention, which will definitely contribute to the area of mental health.

In the test of gender difference, we also found that women show more benign envy compared to men. Previous studies explored the gender difference of envy in special fields. For example, Hill and Buss (49) found that female participants showed more envy than male participants when their companions were more attractive than they were, while male participants became more envious than female participants when their peers had higher-quality sex lives. DelPriore et al. (50) further found that the envy-evoking events of the two genders did not stay stable across time. They changed according to major classes of adaptive challenges facing humans over evolutionary time. In our study, whatever the measures of benign envy and malicious envy, which is the general envy and not involved in specific field of social comparison. Therefore, our results may be an extension to the results of the previous study, showing that female participants tended to display more benign envy than male participants but showed no difference in malicious envy. Furthermore, we also found that women have higher levels of social support than men, which is consistent with previous studies (51, 52). However, in the further analysis, we found that male participants with high levels of gratitude tended to get more social support than female participants, which was also found in previous studies (24, 36, 37). Men may get more return of social support from gratitude than women. This may reflect differences of sex roles in society. Although we found these gender differences in particular variables, the final model actually showed no gender difference, demonstrating that the final model was stable across genders.

Author Contributions

YX: Study design, data collection, data analysis, paper writing. YY: Study design, paper writing, paper revising. XC: Data collection, paper revising.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from Social Science Judge of Hunan (XSP18YBZ117); Natural Science Founds (Project name: the neural basis of transition between benign envy and malicious envy, 2018).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sasa Zhao for her help of the data collecting.

References

1. Emmons RA, McCullough ME. Counting blessings versus burdens: an experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. J Pers Soc Psychol. (2003) 84:377. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.2.377

2. McCullough ME, Tsang JA, Emmons RA. Gratitude in intermediate affective terrain: links of grateful moods to individual differences and daily emotional experience. J Pers Soc Psychol. (2004) 86:295. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.2.295

3. Emmons RA, Shelton CM. Gratitude and the science of positive psychology. In: Snyder CR, Lopez, SJ. editors, Handbook of Positive Psychology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press (2002). p. 459–71.

4. Ma LK, Tunney RJ, Ferguson E. Does gratitude enhance prosociality?: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. (2017) 143:601. doi: 10.1037/bul0000103

6. Wood AM, Froh JJ, Geraghty AW. Gratitude and well-being: a review and theoretical integration. Clin Psychol Rev. (2010) 30:890–905. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.005

7. Kong F, Ding K, Zhao J. The relationships among gratitude, self-esteem, social support and life satisfaction among undergraduate students. J Happiness Stud. (2015) 16:477–89. doi: 10.1007/s10902-014-9519-2

8. Lyubomirsky S, Sheldon KM, Schkade D. Pursuing happiness: the architecture of sustainable change. Rev Gen Psychol. (2005) 9:111. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.9.2.111

9. McCullough ME, Kilpatrick SD, Emmons RA, Larson DB. Is gratitude a moral affect? Psychol Bull. (2001) 127:249. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.2.249

10. Bartlett MY, DeSteno D. Gratitude and prosocial behavior: helping when it costs you. Psychol Sci. (2006) 17:319–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01705.x

11. Tsang JA. Brief report—gratitude and prosocial behaviour: an experimental test of gratitude. Cogn Emot. (2006) 20:138–48. doi: 10.1080/02699930500172341

12. Wood AM, Maltby J, Gillett R, Linley PA, Joseph S. The role of gratitude in the development of social support, stress, and depression: two longitudinal studies. J Res Pers. (2008) 42:854–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2007.11.003

13. McCullough ME, Emmons RA, Tsang JA. The grateful disposition: a conceptual and empirical topography. J Pers Soc Psychol. (2002) 82:112. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.82.1.112

14. Solom R, Watkins PC, McCurrach D, Scheibe D. Thieves of thankfulness: traits that inhibit gratitude. J Posit Psychol. (2017) 12:120–9. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2016.1163408

15. Parrott WG, Smith RH. Distinguishing the experiences of envy and jealousy. J Pers Soc Psychol. (1993) 64:906. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.64.6.906

16. Lange J, Crusius J. The tango of two deadly sins: the social-functional relation of envy and pride. J Pers Soc Psychol. (2015) 109:453. doi: 10.1037/pspi0000026

17. Lange J, Crusius J. Dispositional envy revisited: Unraveling the motivational dynamics of benign and malicious envy. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. (2015) 41:284–94. doi: 10.1177/0146167214564959

18. Van de Ven N, Zeelenberg M, Pieters R. Leveling up and down: the experiences of benign and malicious envy. Emotion (2009) 9:419. doi: 10.1037/a0015669

19. Van de Ven N, Zeelenberg M, Pieters R. Why envy outperforms admiration. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. (2011) 37:784–95. doi: 10.1177/0146167211400421

20. Crusius J, Lange J. What catches the envious eye? Attentional biases within malicious and benign envy. J Exp Soc Psychol. (2014) 55:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2014.05.007

21. Smith RH, Parrott WG, Diener EF, Hoyle RH, Kim SH. Dispositional envy. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. (1999) 25:1007–20. doi: 10.1177/01461672992511008

22. Shiraki Y, Igarashi T. “Paying it forward” via satisfying a basic human need: The need for relatedness satisfaction mediates gratitude and prosocial behavior. Asian J Soc Psychol. (2018). doi: 10.1111/ajsp.12211. [Epub ahead of print].

23. Fredrickson BL. The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Philos Trans R. Soc Lond B Biol Sci. (2004) 359:1367. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1512

24. Froh JJ, Kashdan TB, Ozimkowski KM, Miller N. Who benefits the most from a gratitude intervention in children and adolescents? Examining positive affect as a moderator. J Posit Psychol. (2009) 4:408–22. doi: 10.1080/17439760902992464

25. Horwitz AV, Scheid TL. A Handbook for the Study of Mental Health: Social Contexts, Theories, and Systems. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press (1999).

26. Lakey B, Orehek E. Relational regulation theory: a new approach to explain the link between perceived social support and mental health. Psychol Rev. (2011) 118:482. doi: 10.1037/a0023477

27. Smith RH, Kim SH. Comprehending envy. Psychol. Bull. (2007) 133:46. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.46

28. Gallo LC, Matthews KA. Understanding the association between socioeconomic status and physical health: do negative emotions play a role? Psychol. Bull. (2003) 129:10–51. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.1.10

29. Smith TW, Glazer K, Ruiz JM, Gallo LC. Hostility, anger, aggressiveness, and coronary heart disease: an interpersonal perspective on personality, emotion, and health. J Pers. (2004) 72:1217–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00296.x

30. Suls JM, Bunde J. Anger, anxiety, and depression as risk factors for cardiovascular disease: the problems and implications of overlapping affective dispositions. Psychol Bull. (2005) 131:260–300. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.2.260

31. Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull. (1985) 98:310–57. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310

32. O'Neil JN, Emery CF. Psychosocial vulnerability, hostility, and family history of coronary heart disease among male and female college students. Int J Behav Med. (2002) 9:17–36. doi: 10.1207/S15327558IJBM0901_02

33. Smith TW, Pope MK, Sanders JD, Allred KD, O'Keeffe JL. Cynical hostility at home and work: psychosocial vulnerability across domains. J Res Pers. (1988) 22:525–48. doi: 10.1016/0092-6566(88)90008-6

34. Chen LH, Kee YH. Gratitude and adolescent athletes' well-being. Soc Indic Res. (2008) 89:361–73. doi: 10.1007/s11205-008-9237-4

35. Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. (1988) 52:30–41. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa52012

36. Kong F, Zhao J, You X. Social support mediates the impact of emotional intelligence on mental distress and life satisfaction in Chinese young adults. Pers Individ Dif. (2012) 53:513–17. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2012.04.021

37. Kong F, Zhao J, You X. Emotional intelligence and life satisfaction in Chinese university students: the mediating role of self-esteem and social support. Pers Individ Dif. (2012) 53:1039–43. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2012.07.032

38. Zhao J, Kong F, Wang Y. The role of social support and self-esteem in the relationship between shyness and loneliness. Pers Individ Dif. (2013) 54:577–81. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2012.11.003

39. Little TD, Cunningham WA, Shahar G, Widaman KF. To parcel or not to parcel: exploring the question, weighing the merits. Struct Equ Model. (2002) 9:151–73. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM09021

40. Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model. (1999) 6:1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118

43. Chen LH, Chen MY, Tsai YM. Does gratitude always work? Ambivalence over emotional expression inhibits the beneficial effect of gratitude on well-being. Int J Psychol. (2012) 47:381–92. doi: 10.1080/00207594.2011.632009

44. Cobb S. Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosom Med.(1976) 38:300–14. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197609000-00003

45. Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. (1991) 32:705–14. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-B

46. Thoits PA. Social support as coping assistance. J Consult Clin Psychol. (1986) 54:416. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.54.4.416

47. Thoits PA. Stress, coping, and social support processes: where are we? What next? J Health Soc Behav. (1995), 53–79. doi: 10.2307/2626957

48. Van de Ven N, Zeelenberg M, Pieters R. Appraisal patterns of envy and related emotions. Motiv Emot. (2012) 36:195–204. doi: 10.1007/s11031-011-9235-8

49. Hill SE, Buss DM. Envy and positional bias in the evolutionary psychology of management. MDE Manage Decis Econ. (2006) 27:131–43. doi: 10.1002/mde.1288

50. DelPriore DJ, Hill SE, Buss DM. Envy: functional specificity and sex-differentiated design features. Pers Individ Dif. (2012) 53:317–22. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2012.03.029

51. Antonucci TC, Akiyama H. Social networks in adult life and a preliminary examination of the convoy model. J Gerontol. (1987) 42:519–27. doi: 10.1093/geronj/42.5.519

Keywords: gratitude, malicious envy, benign envy, social support, structural modeling

Citation: Xiang Y, Chao X and Ye Y (2018) Effect of Gratitude on Benign and Malicious Envy: The Mediating Role of Social Support. Front. Psychiatry 9:139. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00139

Received: 06 October 2017; Accepted: 29 March 2018;

Published: 07 May 2018.

Edited by:

Shervin Assari, University of Michigan, United StatesReviewed by:

Masoumeh Dejman, Johns Hopkins University, United StatesJin-Liang Wang, Southwest University, China

Copyright © 2018 Xiang, Chao and Ye. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yanhui Xiang, xyh914@163.com

Yanyan Ye, yipyy603@126.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work.

Yanhui Xiang

Yanhui Xiang Xiaomei Chao

Xiaomei Chao Yanyan Ye

Yanyan Ye