- 1Arthritis Program, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA

- 2Healthy Aging Program, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA

- 3Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA

- 4Epilepsy Program, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA

A Public Health Priority

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has a longstanding commitment to developing and promoting evidence-based strategies to prevent or delay disease and disability (1, 2). Significant among these strategies is support for self-management of chronic diseases. About one-half of all U.S. adults have at least one chronic condition (3) and over two-thirds of Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years or older have two or more chronic conditions (4). Given that the risk of developing a chronic disease increases with advancing age (5), the dramatic aging of the U.S. population underscores the importance of chronic disease self-management supports. Further, effective self management of chronic conditions is essential to achieving a state of health, which is proposed to reflect “the ability to adapt and to self manage” (6).

An effective approach to improve population health requires a strong focus on self-management. CDC’s National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion includes among its four priorities efforts to help ensure that “communities support and clinics refer patients to programs that improve management of chronic conditions” (7). Self-management (e.g., what individuals and families do on a daily basis to feel better and pursue the life they desire) (8) and self-management support (e.g., actions taken by others to support individual self-management) (9) are critical strategies in meeting this priority objective. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services recognized the importance of self-management support in its framework for addressing multiple chronic conditions (MCC). One of the four goals of the framework is to “maximize the use of proven self-care management and other services by individuals with MCC” (10).

Chronic disease self-management support occurs at the intersection of public health, clinical healthcare delivery, social services, aging services networks, and other community resources. In this commentary, we provide a public health perspective on self-management support, identify examples of CDC investment in self-management support activities, and discuss potential future directions. These examples are provided to illustrate the breadth of CDC’s work in this area and are not designed to serve as comprehensive list of CDC’s investment in self-management support.

An International Foundation for Understanding

Consistent with a public health perspective, we advance an expanded definition of self-management support from the International Framework for Chronic Condition Self-Management Support. This definition describes self-management support as a grouping of policies, programs, services, and structures that extend across healthcare, social sectors, and communities to support and improve the way individuals manage their chronic conditions (11). The definition frames self-management support within a social-ecological perspective underscoring individual, interpersonal, community, environmental, and systems levels resources (12). This definition also embraces a life course perspective that attends to individual autonomy and decision-making as well as role changes and other adaptations to life events (13).

Self-management support takes many forms. It includes interventions such as the Chronic Disease Self-Management Program (CDSMP) (14) and the falls prevention programs featured in this special issue (15). It also includes supportive interactions between healthcare providers and patients, proactive follow-up, and social and physical environments that support healthy behaviors such as having safe places to exercise, access to healthy foods, and social norms that combat stigma, promote social participation, and support self-care behaviors (9).

Self-management support interventions are provided in a variety of formats (e.g., one-to-one, small groups, telephone, online/mobile, self-study); and in a variety of settings (e.g., home, healthcare, worksite, community) (9, 12). Although the form and formats vary, the goal of self-management support is consistent: to help individuals and their personal support system acquire and maintain the knowledge, skills, and confidence to do what they need to do to live as well as possible with their chronic condition(s).

Advancing the Study and Application of Self-Management Support

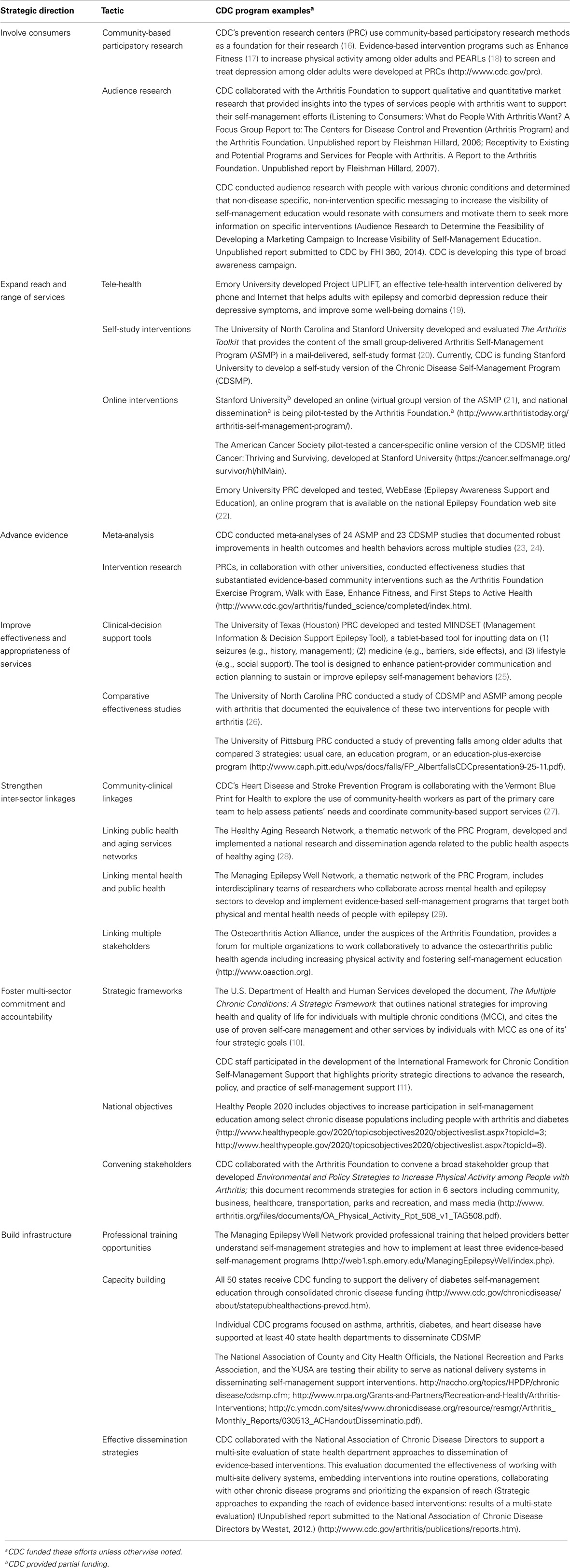

The International Framework for Chronic Condition Self-Management Support identifies seven key strategic directions to move self-management support forward in research, policy, and practice at the local, regional, state, and national levels. These strategic directions are to involve consumers, expand the reach and range of services, advance evidence, improve effectiveness and appropriateness of services, strengthen inter-sector linkages, foster multi-sector commitment and accountability, and build infrastructure. Using this organizing structure (11), in Table 1, we highlight a few select but illustrative examples of CDC’s contributions to the Framework’s seven strategic directions.

Through funded research and other mechanisms, CDC and its partners have employed a variety of strategies to involve consumers by using applied community-based participatory strategies in developing evidence-based programs and audience research. To expand the range and reach of services, CDC supports the development, evaluation, and dissemination of a variety of small group, tele-health, self-study, and online self-management support tools. To advance evidence, CDC investigators conduct systematic reviews of the literature and CDC funds applied prevention research to establish or strengthen the evidence-base of programs and policies. To improve the effectiveness and appropriateness of services, CDC supports comparative effectiveness studies and research designed to develop and test clinical-decision support tools. In terms of efforts to strengthen inter-sector linkages, CDC supports community-clinical collaborations and makes linkages across public health sectors. CDC also helps to foster multi-sector commitment and accountability through the development of new frameworks and guidelines. Finally, CDC invests in building infrastructure to deliver self-management support intervention programs at the national, state, and local levels systems initiatives.

Sustaining Self-Management Support: Gaps and Opportunities

The need to advance efforts in self-management support is well recognized in the public health arena. However, challenges remain and several research questions are yet unanswered. Such questions include how to identify the essential elements of an intervention, how to best target effective interventions to specific audiences, and how to determine the effect of self-management support on critical public health outcomes and biometric measures such as hemoglobin A1c and blood pressure. Additional comparative effectiveness and cost effectiveness research studies of self-management support interventions are necessary. Importantly, selected papers in this special issue will help address these issues.

If self-management support interventions are to achieve their potential for public health impact, they need to be integrated into comprehensive chronic disease management strategies at the national, state, and local levels, and across sectors. Given the large and diverse population of people living with chronic conditions, engagement of multiple organizations across various sectors is required to reach those in need. Ideally, self-management support will become an integral element of clinical care standards of care (30), part of the routine menu of services offered by a variety of community agencies, and an essential component of community chronic disease control efforts. Finally, sustaining self-management support will require the infrastructure as well as multi-sectoral resources to reach people where they live, learn, work, and engage with their family and community. Creative financing mechanisms will need to be developed or expanded to ensure wide availability of evidence-based self-management support.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is supporting a wide variety of self-management support activities across multiple strategic directions. CDC supported activities exemplify a comprehensive view of self-management support that encompasses both health-enhancing individual behaviors and physical and social environmental contexts that influence self-management behaviors. To advance self-management support, several important areas of research need to be conducted, broad-based organizational engagement needs to occur, and delivery capacity infrastructure and financing mechanisms need to be established or expanded. Despite these challenges, it remains essential to create self-management support services and environmental supports that allow people to live well with their chronic condition.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

This paper is included in the Research Topic, “Evidence-Based Programming for Older Adults.” This Research Topic received partial funding from multiple government and private organizations/agencies; however, the views, findings, and conclusions in these articles are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of these organizations/agencies. All papers published in the Research Topic received peer review from members of the Frontiers in Public Health (Public Health Education and Promotion section) panel of Review Editors. Because this Research Topic represents work closely associated with a nationwide evidence-based movement in the US, many of the authors and/or Review Editors may have worked together previously in some fashion. Review Editors were purposively selected based on their expertise with evaluation and/or evidence-based programming for older adults. Review Editors were independent of named authors on any given article published in this volume.

Acknowledgments

The findings and conclusions in this commentary are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

1. Briss PA, Zaza S, Pappaioanou M, Fielding J, Wright-De Agüero L, Truman BI, et al. Developing an evidence-based guide to community preventive services-methods. Am J Prev Med (2000) 18(1S):35–43. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(99)00119-1

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

2. Kohatsu ND, Robinson JG, Torner JC. Evidence-based public health: an evolving concept. Am J Prev Med (2004) 27(5):417–21. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2004.07.019

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

3. Anderson G. Chronic Care: Making the Case for Ongoing Care. Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (2010). Available from: www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/reports/2010/rwjf54583

4. Lochner KA, Cox CS. Prevalence of multiple chronic conditions among Medicare beneficiaries, United States, 2010. Prev Chronic Dis (2013) 10:120137. doi:10.5888/pcd10.120137

5. Ward BW, Schiller JS. Prevalence of multiple chronic conditions among US adults: estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, 2010. Prev Chronic Dis (2013) 10:120203. doi:10.5888/pcd10.120203

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

6. Huber M, Knottnerous JA, Green L, van der Horst H, Leonard B, Lorig K, et al. How should we define health? BMJ (2011) 343:d4163. doi:10.1136/bmj.d4163

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 24/7: Saving Lives. Protecting People.TM National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) (2013). Available from: www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/about/public-health-approach.htm

8. Brady TJ, Sniezek JE, Conn D. Enhancing patient self-management in clinical practice. Bull Rheum Dis (2000) 49(9):1–4.

9. Brady TJ. Strategies to support self-management in osteoarthritis. Am J Nurs (2012) 112:S54–60. doi:10.1097/01.NAJ.0000412653.56291.ab

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

10. Parekh AK, Goodman RA, Gordon C, Koh HK, The HHS Interagency Workgroup on Multiple Chronic Conditions. Managing multiple chronic conditions: a strategic framework for improving health outcomes and quality of life. Public Health Rep (2011) 126(4):460–71.

11. Brady TJ, Mills S, Sargious P, Ziabakhsh S. An international framework for chronic condition self management support: results from an international electronic consultation process [abstract]. Arthritis Rheum (2012) S10:S1011–2. doi:10.1002/art.38216

12. Fisher EB, Brownson CA, O’Toole ML, Shetty G, Anwuri VV, Glasgow RE. Ecological approaches to self-management: the case of diabetes. Am J Public Health (2005) 95:1523–35. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2005.066084

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

13. Elder GH, Johnson MK, Crosnoe R. The emergence and development of life course theory. In: Mortimer JT, Shanahan MJ, editors. Handbook of the Life Course. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum (2003). p. 3–22.

14. Lorig KR, Sobel DS, Stewart AL, Brown BW, Bandura A, Ritter P, et al. Evidence suggesting that a chronic disease self-management program can improve health status while reducing hospitalization: a randomized trial. Med Care (1999) 37:5–14. doi:10.1097/00005650-199901000-00003

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

15. Stevens JA. A CDC Compendium of Effective Fall Interventions: What Works for Community-Dwelling Older Adults. 2nd ed. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US), National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (2010).

16. Faridi Z, Grunbaum JA, Gray BS, Franks A, Simoes E. Community-based participatory research: necessary next steps. Prev Chronic Dis (2007) 4:A70. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2007/jul/06_0182.htm

17. Belza B, Snyder S, Thompson M, LoGerfo J. From research to practice: EnhanceFitness, an innovative community-based senior exercise program. Topics Geriat Rehab (2010) 26(4):299–309.

18. Ciechanowski P, Wagner E, Schmaling K, Schwartz S, Williams B, Diehr P, et al. Community-integrated home-based depression treatment in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA (2004) 291(13):1569–77. doi:10.1001/jama.291.13.1569

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

19. Thompson NJ, Walker ER, Obolensky N, Winning A, Barmon C, DiIorio C, et al. Distance delivery of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: project UPLIFT. Epilepsy Behav (2010) 19(3):247–54. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2010.07.031

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

20. Goeppinger J, Lorig KR, Ritter PL, Mutatkar S, Villa F, Gizlice Z. Mail-delivered arthritis self-management tool kit: a randomized trial and longitudinal follow-up. Arthritis Rheum (2009) 61(7):867–75. doi:10.1002/art.24587

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

21. Lorig KR, Ritter PL, Laurent D, Plant K. The internet-based arthritis self-management program: a one-year randomized trial for patients with arthritis or fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum (2008) 59(7):1009–17. doi:10.1002/art.23817

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

22. DiIorio C, Bamps Y, Escoffery C, Reisinger-Walker E. Results of a randomized controlled trial: evaluating WebEase, an online epilepsy self-management program. Epilepsy Behav (2011) 22(3):469–74. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2011.07.030

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

23. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sorting through the Evidence of the Arthritis Self-Management Program and the Chronic Disease Self-Management Program: Executive Summary of the ASMP/CDSMP Meta-Analyses. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) (2011). Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/arthritis/docs/ASMP-executive-summary.pdf

24. Brady TJ, Murphy LM, O’Colmain B, Beauchesne D, Daniels B, Greenberg M, et al. A meta-analysis of health status, health behaviors and health care utilization outcomes of the chronic disease self-management program. Prev Chronic Dis (2013) 10:120112. doi:10.5888/pcd10.120112

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

25. Shegog R, Begley CE, Harding A, Dubinsky S, Goldmsith C, Omotola H, et al. Description and feasibility of MINDSET: a clinic decision aid for epilepsy self-management. Epilepsy Behav (2013) 29:527–36. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2013.09.023

26. Goeppinger J, Armstrong B, Schwartz T, Ensley D, Brady T. Self-management education for persons with arthritis: managing co-morbidities and eliminating health disparities. Arthritis Rheum (2007) 57(6):1081–8. doi:10.1002/art.22896

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

27. Vermont Blueprint for Health: 2011 Annual Report [Internet]. Williston, VT: Department of Vermont Health Access (2012). Available from: http://hcr.vermont.gov/sites/hcr/files/Blueprint%20Annual%20Report%20Final%2001%2026%2012%20_Final_.pdf

28. Wilcox S, Altpeter M, Anderson LA, Belza B, Bryant L, Jones DL, et al. The healthy aging research network: resources for building capacity for public health and aging practice. Am J Health Promot (2013) 28(1):2–6. doi:10.4278/ajhp.121116-CIT-564

29. CDC Prevention Research Centers. Managing Epilepsy Well Network: Putting Collective Wisdom to Work for People with Epilepsy. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US), National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (2013). Available from: www.cdc.gov/epilepsy/pdfs/mew-booklet-tagged-508.pdf

30. National Committee for Quality Assurance. NCQA Patient-Centered Medical Home: A New Model of Care Delivery, Patient-Centered Medical Homes Enhance Primary Care Practices. Washington, DC: National Committee for Quality Assurance (2014). Available from: www.ncqa.org/Portals/0/PCMH%20brochure-web.pdf

Keywords: self-management support, evidence-based interventions public health, life course, prevention research

Citation: Brady TJ, Anderson LA and Kobau R (2015) Chronic disease self-management support: public health perspectives. Front. Public Health 2:234. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2014.00234

Received: 16 June 2014; Accepted: 28 October 2014;

Published online: 27 April 2015.

Edited by:

Matthew Lee Smith, The University of Georgia, USAReviewed by:

Heather Honoré Goltz, University of Houston-Downtown, USACopyright: © 2015 Brady, Anderson and Kobau. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: tob9@cdc.gov

Teresa J. Brady

Teresa J. Brady Lynda A. Anderson

Lynda A. Anderson Rosemarie Kobau

Rosemarie Kobau