- 1College of Medicine, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, United States

- 2Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, United States

Background: Helicobacter pylori infection is associated with the development of chronic gastritis, peptic ulcer disease, and gastric cancer. Current clinical recommendations are that H. pylori test-and-treat should be individualized based on comorbidities and patient preferences among populations at increased risk for certain morbidities. However, knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding H. pylori among potential patient populations are largely unknown.

Materials: We conducted a literature review to assess knowledge, attitudes, and practices of patients or community populations around H. pylori transmission, prevention, and associated morbidity.

Results: Nine studies met the inclusion criteria, all published between 1997 and 2014. Eight studies evaluated perception of H. pylori among at-risk populations, while one study evaluated perception among a general population. The studies suggest inconsistencies between the perceptions of these populations and the established understanding of knowledge, attitude, and preventive practices for H. pylori among even at-risk populations.

Conclusion: To adequately respond to current test-and-treat recommendations for treatment of H. pylori, general population education must be implemented, especially among at-risk populations. Further work is needed within at-risk populations in the United States to determine prevalence of H. pylori and their current knowledge if adequate prevention strategies are to be designed.

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori is a gram-negative bacterium that predominately infects the lining of the stomach. H. pylori is associated with the development of chronic gastritis, peptic ulcer disease, and gastric cancer. Worldwide, gastric cancer is the fifth most common cancer and third leading cause of cancer-related death (1). It has been estimated that 78% of all gastric cancer cases, and 89% of non-cardiac cases, can be attributed to chronic H. pylori infection (2). The development of gastric cancer from H. pylori, which involves a multistep process from chronic gastritis to atrophic gastritis to intestinal metaplasia to dysplasia to gastric cancer, can take decades to develop (3). This slow progression provides an opportunity for early detection and treatment of H. pylori, leading to the prevention of gastric cancer.

Helicobacter pylori screening and prevention among at-risk groups may reduce certain diseases and “test-and-treat” should be individualized based on comorbid illness and patient preferences (4). These at-risk populations include individuals with a number of potential indications, including a confirmed history of peptic ulcer disease and gastric MALT lymphoma (4). In the United States, higher prevalence of H. pylori has been reported among individuals living close the US/Mexico border, as well as among American Indians and Alaska natives (5–7). However, among at-risk populations, the current level of knowledge and behaviors and risk perception are unknown. This information is needed if “test-and-treat” strategies are to be successfully employed for specific populations. The aim of this review is to examine the current literature with respect to public perceptions of the impact of H. pylori.

Materials and Methods

A framework to assess knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAPs) was defined based on the World Health Organization Guide to Developing Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice Surveys (8). In the context of this review, “Knowledge” referred to general knowledge about H. pylori including transmission, course of infection, disease sequelae, risk/protective factors, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. “Attitudes” referred to individual, peer, and community risk perception of getting H. pylori or its disease sequelae. “Practices” corresponded to actions people might take to prevent H. pylori infection, including hand washing, safe food preparation, and source of drinking water. These latter practices were sought because evidence suggests fecal–oral transmission may play a role in H. pylori transmission (9), and these practices were outlined by the National Institutes of Health as ways to reduce chances of H. pylori infection (10).

A literature search was conducted in April 2017 in PubMed using (“Helicobacter” OR “H. pylori”) AND (“survey” OR “questionnaire”) AND (“knowledge” OR “attitudes” OR “practices”) as search terms. Inclusion criteria were that the study collected primary data from at-risk or members of the general population and that the study incorporated a survey to assess participants own knowledge, attitudes, or practices regarding H. pylori. There were no other exclusion terms (e.g., language or date of publication).

Results

The initial search terms yielded 133 results, with two additional studies identified through follow-up of references. After title and abstract screening to exclude articles not focused on potential patient KAP, 15 articles remained. After reviewing full text, an additional six studies were rejected because the survey included only demographic and/or clinical history without any assessment of KAP (n = 5), or H. pylori was not the primary focus of study (n = 1).

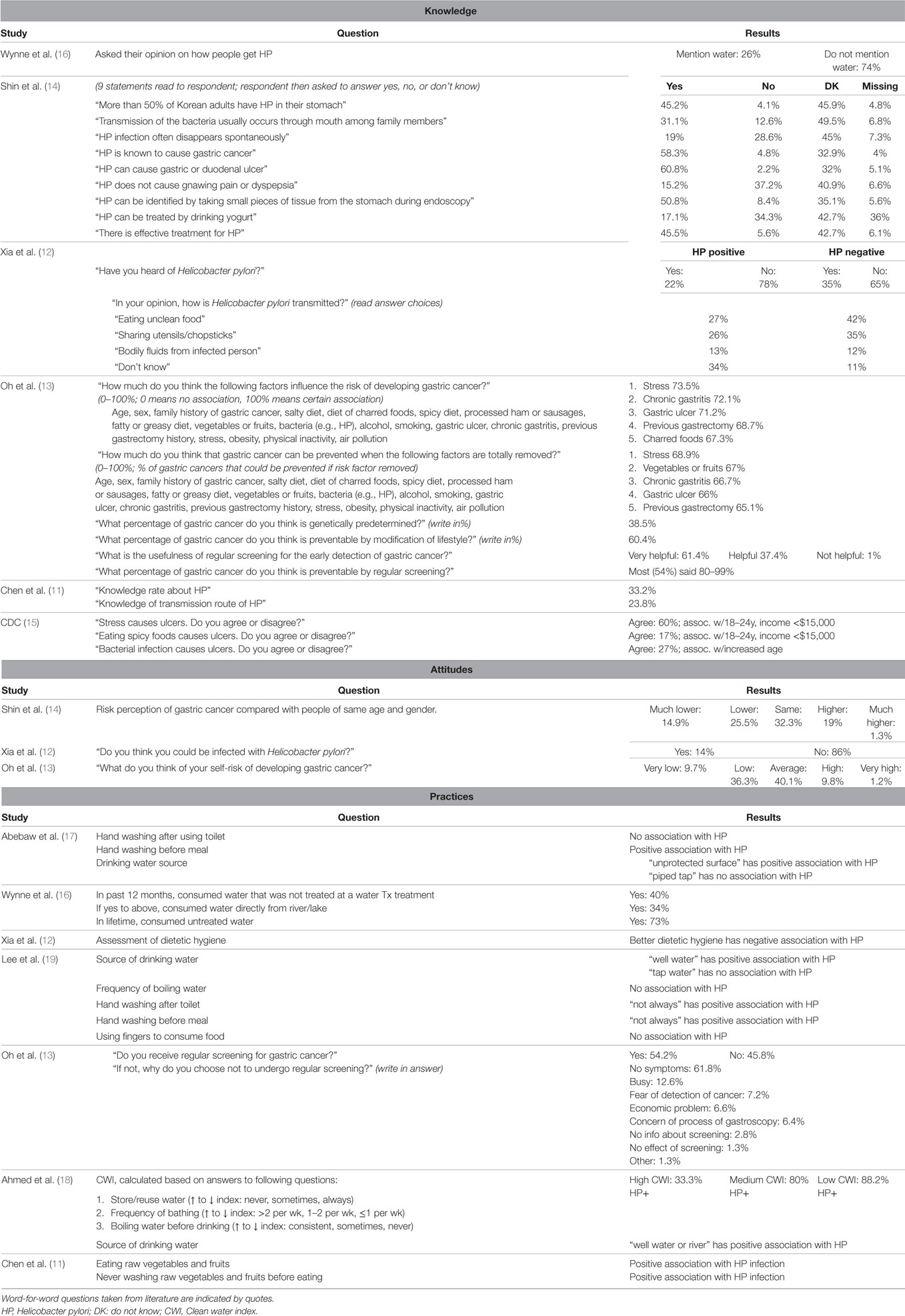

Of the nine studies included in this review, two were conducted in eastern China (11, 12), two in South Korea (13, 14), two in North America (15, 16), and one each in Ethiopia (17), India (18), and Malaysia (19). All studies focused on populations at increased risk for gastric cancer, except the US population-based survey to assess and promote awareness (15). Within this search, no publications were found which specifically addressed gaps in KAP among the general population regarding risks associated with acquiring H. pylori infection. All studies were published between 1997 and 2014. For each study, the type of questions used in the survey tool were classified into demographic, clinical history, knowledge, attitude, or practice related questions. A summary of the questions (along with results) is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of questions and replies nested within studies and ordered by publication date for knowledge, attitudes, and practices. Word-for-word questions taken from literature are indicated by quotes.

Knowledge

Six studies reported on H. pylori knowledge (11–16). General knowledge about H. pylori was poor across all studies. Of the two studies that asked whether participants had heard of H. pylori, only 22–35% of respondents answered “yes” (11, 12). Interestingly, one study found that those who tested negative for H. pylori had heard of H. pylori more often than those who tested positive (12).

Knowledge about H. pylori transmission was also generally poor. When asked how people can acquire the infection, only 26% of participants mentioned water (16). When asked whether oral transmission was usual among family members, 31.1% of participants responded “yes,” 12.6% responded “no,” and 49.5% responded “do not know” (14). When asked about transmission, people who tested positive for H. pylori showed less understanding than those who tested negative (12). One study, asking about transmission found only 23.8% of respondents correctly answered that H. pylori can be transmitted by unsafe food preparation and water sources (11).

The two studies from South Korea evaluated knowledge of H. pylori as it relates to gastric cancer. Among healthy Korean adults undergoing screening via upper endoscopy 58.3% of respondents answered “yes,” that H. pylori is known to cause gastric cancer, while 4.8% answered “no,” and 32.9% responded “do not know” (14). Randomly selected respondents in the South Korean population-based survey were asked to what degree individual factors were associated with developing and preventing gastric cancer (13). Respondents believed stress was the highest risk factor for developing gastric cancer, followed by gastric lesions (including chronic gastritis, gastric ulcer, and previous gastrectomy) and eating charred foods. Respondents believed that removing stress would have the greatest impact on preventing gastric cancer, followed by eating vegetables and fruits, and removing gastric lesions.

Two studies evaluated knowledge of H. pylori and its relationship to peptic ulcer disease. Shin et al. (14) asked if H. pylori can cause gastric or duodenal ulcers; 60.8% answered “yes,” 2.2% answered “no,” and 32% answered “do not know” (14). A US population-based survey from 1997 asked respondents whether stress causes ulcers (yes: 60%), eating spicy foods causes ulcers (yes: 17%), and bacterial infection causes ulcers (yes: 27%) (15).

Attitudes

Three studies asked questions regarding attitudes related to H. pylori/gastric cancer (12–14). All three of these studies assessed perception of self-risk for either contracting H. pylori or developing gastric cancer. Shin et al. (14) found that most people viewed their own risk as “same” or “lower” when compared with people of same age and gender. Oh et al. (13) found that most people viewed their own risk for developing gastric cancer as average or low. Xia et al. (12) found that 86% of people did not think they were infected with H. pylori despite that within this population, H. pylori prevalence was 41%.

Practices

Seven studies asked questions related to H. pylori prevention practices (11–13, 16–19). Generally, good hand washing practices after using the toilet and before eating/preparing meal, safe food practices, and drinking water from a clean source were associated with less H. pylori infection. Interestingly, Abebaw et al. (17) found hand washing before meals was associated with higher prevalence of H. pylori, and hand washing after using toilet carried no association with H. pylori prevalence. However, this result conflicts with what is generally understood about this association, and other studies reviewed here found that hand washing “not always” after toilet and “not always” before meal were associated with higher H. pylori prevalence (19).

Discussion

This review identified nine studies that surveyed public KAPs regarding H. pylori. The limited number of publications on this topic is surprising given the potential benefit of H. pylori “test-and-treat” in preventing gastric cancer as well as the need for involvement of patient preferences in testing and treatment decisions for at-risk populations (4). The lack of studies in the US is disconcerting given that, while trends in gastric cancer mortality from 2004 to 2013 are decreasing nationally among all other ethnicities, they remain unchanged among American Indian/Alaska Natives (SEER.cancer.gov) (20).

Based on this review, there appears to be limited knowledge about H. pylori among the general population, especially with respect to transmission and its association with gastric cancer. Interestingly, the association between H. pylori and ulcers may be more widely known than the association between H. pylori and gastric cancer (14). However, it appears that many people regard stress as the highest risk factor not only for ulcers, but for gastric cancer as well (13, 15).

This literature review highlights lack of studies evaluating public awareness of H. pylori, particularly among populations at increased risk for gastric cancer. With this insight, provider- and patient-based strategies such as screening, surveillance, and outreach programs can be developed to reduce gastric cancer attributable to H. pylori infection among these at-risk subpopulations (21, 22).

Author Contributions

LD and EO developed the original scope of the review. LD and HB conducted the literature search and review. All authors were involved in manuscript preparation, approved the final version, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the University of Arizona Helicobacter pylori Research Workgroup for helpful input during the development of the project.

Funding

This work was partly supported by the Art Chapa Foundation for Gastric Cancer Prevention and the University of Arizona Cancer Center Cancer Disparities Grant.

References

1. Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin (2015) 65(2):87–108. doi:10.3322/caac.21262

2. IARC Helicobacter pylori Working Group. Helicobacter Pylori Eradication as a Strategy for Preventing Gastric Cancer. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer (2014). Available from: https://www.iarc.fr/en/publications/pdfs-online/wrk/wrk8/Helicobacter_pylori_Eradication.pdf

3. Correa P. Human gastric carcinogenesis: a multistep and multifactorial process – First American Cancer Society Award Lecture on Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention. Cancer Res (1992) 52(24):6735–40.

4. Chey W, Leontiadis GI, Howden CW, Moss SF. ACG clinical guideline: treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol (2017) 112:212–38. doi:10.1038/ajg.2016.563

5. Goodman KJ, Jacobson K, Veldhuyzen van Zanten S. Helicobacter pylori infection in Canadian and related Arctic Aboriginal populations. Can J Gastroenterol (2008) 22:289–95. doi:10.1155/2008/258610

6. Cardenas VM, Mena KD, Ortiz M, Karri S, Variyam E, Behravesh CB, et al. Hyperendemic H. pylori and tapeworm infections in a U.S.-Mexico border population. Pub Health Rep (2010) 125(3):441–7. doi:10.1177/003335491012500313

7. Esquivel RF, Holve S, Landan D, Silber G, Peacock J, Ramirez FC. Seroepidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection in Native Americans. Am J Gastroenterol (2000) 95:2494. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02644.x

8. World Health Organization. A Guide to Developing Knowledge, Attitude and Practice Surveys. Switzerland: WHO (2008). Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/43790/1/9789241596176_eng.pdf

9. Bui D, Brown HE, Harris RB, Oren E. Serologic evidence for fecal–oral transmission of Helicobacter pylori. Am J Trop Med Hyg (2016) 94(1):82–8. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.15-0297

10. National Institutes of Health. Peptic Ulcer Disease and H. Pylori. NIH (2014). Available from: http://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-topics/digestive-diseases/peptic-ulcer/Documents/hpylori_508.pdf

11. Chen SY, Liu TS, Fan XM, Dong L, Fang GT, Tu CT, et al. [Epidemiological study of Helicobacter pylori infection and its risk factors in Shanghai]. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi (2005) 85(12):802–6.

12. Xia P, Ma M-F, Wang W. Status of Helicobacter pylori infection among migrant workers in Shijiazhuang, China. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev (2012) 13(4):1167–70. doi:10.7314/APJCP.2012.13.4.1167

13. Oh D-Y, Choi KS, Shin H-R, Bang Y-J. Public awareness of gastric cancer risk factors and disease screening in a high risk region: a population-based study. Cancer Res Treat (2009) 41(2):59–66. doi:10.4143/crt.2009.41.2.59

14. Shin DW, Cho J, Kim SH, Choi HC, Son KY, Park SM, et al. Preferences for the “screen and treat” strategy of Helicobacter pylori to prevent gastric cancer in healthy Korean populations. Helicobacter (2013) 18(4):262–9. doi:10.1111/hel.12039

15. CDC. Knowledge about causes of peptic ulcer disease – United States, March-April 1997. JAMA (1997) 278(21):1731–1731. doi:10.1001/jama.1997.03550210027017

16. Wynne A, Hastings EV, Colquhoun A, Chang HJ, Goodman KJ, CANHelp Working Group. Untreated water and Helicobacter pylori: perceptions and behaviors in a Northern Canadian community. Int J Circumpolar Health (2013) 72:22447. doi:10.3402/ijch.v72i0.22447

17. Abebaw W, Kibret M, Abera B. Prevalence and risk factors of H. pylori from dyspeptic patients in northwest Ethiopia: a hospital based cross-sectional study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev (2014) 15(11):4459–63. doi:10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.11.4459

18. Ahmed KS, Khan AA, Ahmed I, Tiwari SK, Habeeb A, Ahi JD, et al. Impact of household hygiene and water source on the prevalence and transmission of Helicobacter pylori: a South Indian perspective. Singapore Med J (2007) 48(6):543–9.

19. Lee YY, Ismail AW, Mustaffa N, Musa KI, Majid NA, Choo KE, et al. Sociocultural and dietary practices among Malay subjects in the north-eastern region of Peninsular Malaysia: a region of low prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter (2012) 17(1):54–61. doi:10.1111/j.1523-5378.2011.00917.x

20. National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. Trends in SEER Incidence and U.S. Mortality. (2017). Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/archive/csr/1975_2013/results_merged/sect_24_stomach.pdf

21. Kim GH, Liang PS, Bang SJ, Hwang JH. Screening and surveillance for gastric cancer in the United States: is it needed? Gastrointest Endosc (2016) 84(1):18–28. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2016.02.028

22. Consumer Health Digest. Stomach Cancer Awareness Month: Join to Fight Against this Disease. (2017). Available from: https://www.consumerhealthdigest.com/health-awareness/stomach-cancer-awareness-month.html

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, knowledge, attitudes, practices, general population

Citation: Driscoll LJ, Brown HE, Harris RB and Oren E (2017) Population Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice Regarding Helicobacter pylori Transmission and Outcomes: A Literature Review. Front. Public Health 5:144. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00144

Received: 08 April 2017; Accepted: 08 June 2017;

Published: 23 June 2017

Edited by:

Harshad Thakur, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, IndiaReviewed by:

William Augustine Toscano, University of Minnesota, United StatesSharyl Kidd Kinney, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, United States

Copyright: © 2017 Driscoll, Brown, Harris and Oren. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Eyal Oren, eoren@email.arizona.edu

Lisa J. Driscoll

Lisa J. Driscoll Heidi E. Brown

Heidi E. Brown Robin B. Harris

Robin B. Harris Eyal Oren

Eyal Oren