Soft Robotic Haptic Interface with Variable Stiffness for Rehabilitation of Neurologically Impaired Hand Function

- 1Bio-Inspired Mechatronics Laboratory, The Polytechnic School, Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering, Arizona State University, Mesa, AZ, United States

- 2Neural Control of Movement Laboratory, School of Biological Health Systems Engineering, Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, United States

- 3Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, University of Central Florida, Orlando, FL, United States

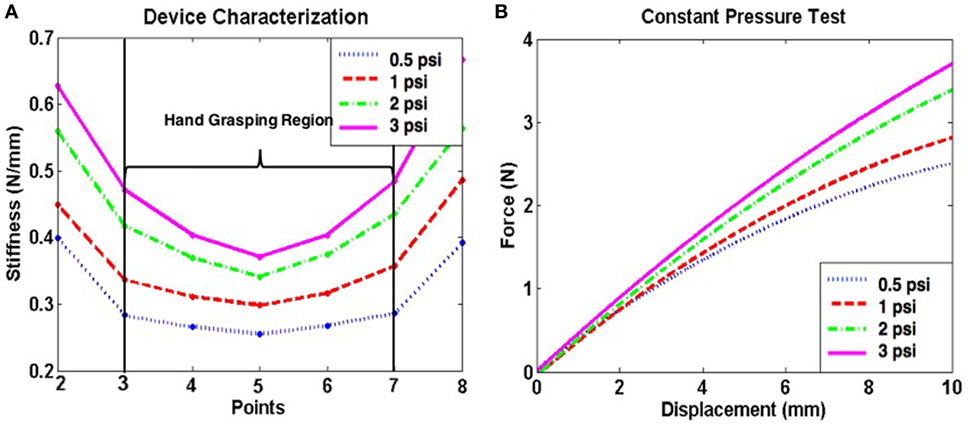

The human hand comprises complex sensorimotor functions that can be impaired by neurological diseases and traumatic injuries. Effective rehabilitation can bring the impaired hand back to a functional state because of the plasticity of the central nervous system to relearn and remodel the lost synapses in the brain. Current rehabilitation therapies focus on strengthening motor skills, such as grasping, employ multiple objects of varying stiffness so that affected persons can experience a wide range of strength training. These devices have limited range of stiffness due to the rigid mechanisms employed in their variable stiffness actuators. This paper presents a novel soft robotic haptic device for neuromuscular rehabilitation of the hand, which is designed to offer adjustable stiffness and can be utilized in both clinical and home settings. The device eliminates the need for multiple objects by employing a pneumatic soft structure made with highly compliant materials that act as the actuator of the haptic interface. It is made with interchangeable sleeves that can be customized to include materials of varying stiffness to increase the upper limit of the stiffness range. The device is fabricated using existing 3D printing technologies, and polymer molding and casting techniques, thus keeping the cost low and throughput high. The haptic interface is linked to either an open-loop system that allows for an increased pressure during usage or closed-loop system that provides pressure regulation in accordance to the stiffness the user specifies. Preliminary evaluation is performed to characterize the effective controllable region of variance in stiffness. It was found that the region of controllable stiffness was between points 3 and 7, where the stiffness appeared to plateau with each increase in pressure. The two control systems are tested to derive relationships between internal pressure, grasping force exertion on the surface, and displacement using multiple probing points on the haptic device. Additional quantitative evaluation is performed with study participants and juxtaposed to a qualitative analysis to ensure adequate perception in compliance variance. The qualitative evaluation showed that greater than 60% of the trials resulted in the correct perception of stiffness in the haptic device.

Introduction

The human hand is a complex sensorimotor apparatus that consists of many joints, muscles, and sensory receptors. Such complexity allows for skillful and dexterous manual actions in activities of daily living (ADL). When the sensorimotor function of hand is impaired by neurological diseases or traumatic injuries, the quality of life of the affected individual could be severely impacted. For example, stroke is a condition that is broadly defined as a loss in brain function due to necrotic cell death stemming from a sudden loss in blood supply within the cranium (Hankey, 2017). This event can lead to a multitude of repercussions on sensorimotor function, one of which being impaired hand control such as weakened grip strength (Foulkes et al., 1988; Duncan et al., 1994; Nakayama et al., 1994; Jørgensen et al., 1995; Wilkinson et al., 1997; Winstein et al., 2004; Legg et al., 2007). Other potential causes of impaired hand function include cerebral palsy, multiple sclerosis, and amputation. Therefore, effective rehabilitation to help patients regain functional hand control is critically important in clinical practice. It has been shown that recovery of sensory motor function relies on the plasticity of the central nervous system to relearn and remodel the brain (Warraich and Kleim, 2010). Specifically, there are several factors that are known to contribute to neuroplasticity (Kleim and Jones, 2008): specificity, number of repetition, training intensity, time, and salience. However, existing physical therapy of hand is limited by the resource and accessibility, leading to inadequate dosage and lack of patients’ motivation. Robot-assisted hand rehabilitation has recently attracted a lot of attention because robotic devices have the advantage to provide (1) enriched environment to strengthen motivation, (2) increase number of repetition through automated control, and (3) progressive intensity levels that adapts to patient’s need (for review, see Balasubramanian et al., 2010).

Specifically, haptic interfaces and variable stiffness mechanisms are usually incorporated into robotic rehabilitation devices to provide varying difficulties by adjusting force output or stiffness. For example, the LINarm++ is a rehabilitative device that appropriates variable stiffness actuators with multimodal sensors to provide changing resistance in a physical environment in which users performs arm movement (Malosio et al., 2016; Spagnuolo et al., 2017). This device also encompasses a functional electrical stimulation system which has been shown to promote motor recovery in upper limb rehabilitation (Popović and Popović, 2006). The Haptic Knob is a device that trains stroke patients’ grasping movements, and wrist pronation and supination motions by rotating a dial that is able to produce forces and torques up to 50 N and 1.5 Nm, respectively, depending on the patient’s level of impairment (Lambercy et al., 2009). The GripAble is a handheld rehabilitative device that allows the patient to squeeze, lift, and rotate to play a video game with increasing difficulty and gives feedback through vibration in response to the patient’s performance (Mace et al., 2015, 2017). The MIT-MANUS, a planar rehabilitation robot, also has a hand-module that converts rotary motions to linear motions, and in turn allows for controllable impedance in the device (Masia et al., 2006). In addition, pneumatic particle jamming systems have been designed to provide users with haptic feedback by changing the stiffness and geometry of the surface the user presses on with their fingertips (Stanley et al., 2013; Genecov et al., 2014). These devices and systems, however, are either costly and bulky due to complex mechanical design or have limited range of stiffness due to passive mechanical components.

To overcome these limitations, this paper proposes the design of a novel pneumatically actuated soft robotics-based variable stiffness haptic interface to support rehabilitation of sensorimotor function of hands (Figure 1). Soft robotics is a rapidly growing field that utilizes highly compliant materials that are fluidic actuated to effectively adapt to shapes and constraints that traditionally rigid machines are unable to Majidi (2014) and Polygerinos et al. (2017). Several soft-robotics devices have been developed to provide assistance to stroke patients, but none of these has been designed as resistive training devices. An example of an existing device includes the use of soft actuators that bend, twist, and extend through finger-like motions in a rehabilitative exoglove to be worn by stroke patients (Polygerinos et al., 2015a,b; Yap et al., 2017). A variable stiffness device that employs soft-robotics allows a greater range of stiffness to be implemented since there is minimal or no impedance to the initial stiffness of the device. In addition, soft robotics methods allow devices to be manufactured with lowered cost and have much less complexity, thus suitable to be used not only inpatient but also outpatient hand rehabilitative services (Taylor et al., 1996; Godwin et al., 2011).

In Section “Materials and Methods” of this paper, the materials and methods employed in designing and fabricating the soft robotic haptic interface are described, including the design criteria of the prototype. This section also describes the methodology for a stiffness perception test on healthy participant with the proposed device. In addition, the overall closed-loop control system of the device to provide pressure regulation is presented in this section. Section “Results” describes the preliminary results obtained from characterization of the device’s varying stiffness in response to changing pressure inputs, and the subjective evaluation of perceived stiffness obtained from test participants. Finally, Section “Discussion” includes an overall discussion of open question and future research directions.

Materials and Methods

Soft Robotic Haptic Interface Design

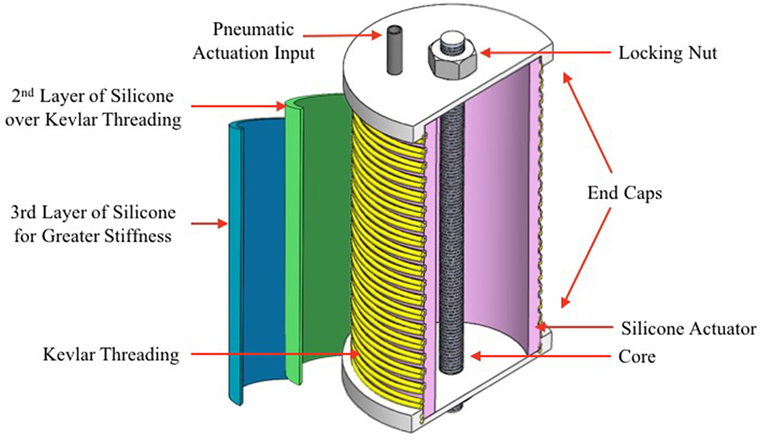

As shown in Figure 2 the device is designed as a cylindrical handle of 40 mm diameter since this diameter has been shown to be most effective in enabling high grip forces in humans (Seo et al., 2008). The average male hand width, defined as the distance from the second to the fifth metacarpophalangeal joints, is approximately 83 mm (Seo et al., 2008; Geetha et al., 2015). We designed the cylindrical device’s height to be 120 mm. The approximately 40 mm additional length was added to ensure that the entire body of the device fits in a patient’s grip, accommodate for hand widths larger than the average, and to account for higher stiffness in areas closer to the end caps of the device. The male hand width is used as the basis of the design since on average the male hand is larger than the female hand. The device is modeled using a computer-aided design software before a mold was made for its body to be cast out of silicone elastomer material and the end caps are 3D printed. The mold of the body included groves in a helical pattern along the body of the device to facilitate the fiber winding process during fabrication, as described in the fabrication section.

Figure 2. Cross-section of the computer-aided design model used in the design for the soft haptic interface with labels of the key components.

Soft Robotic Haptic Interface Fabrication

The body of the device is fabricated based on the multistep molding and casting technique that have been established for creating fiber-reinforced soft actuators (Deimel and Brock, 2013; Bishop-Moser and Kota, 2015; Polygerinos et al., 2015a,b). However, some features and components are modified according to the goal of constraining the device from expanding vertically and horizontally, as well as to prevent bending and twisting motions. Instead of a hemisphere or a rectangle, the body of the mold is made in a circular design to achieve a cylindrical handheld device, and 3D printed (Fortus 250MC printer, Stratasys Ltd., MN, USA). The first layer is casted with the printed mold using a shore hardness 10 A silicone rubber (Dragon Skin 10, Smooth-on Inc., PA, USA) with 2-mm thickness. End caps of 50-mm diameter and 5-mm thickness are 3D printed (Fortus 450MC printer, Stratasys Ltd., MN, USA).

The caps included a 6-mm-diameter hole in the center to introduce a 178-mm-long threaded rod, acting as core, which is fastened on both ends with locking nuts. In addition, a 3-mm-diameter hole is made approximately 4 mm off the edge of the first hole to introduce a tube for pneumatic actuation. The end caps are attached to the body of the actuator using silicone adhesive (Sil-Poxy Adhesive, Smooth-on Inc., PA, USA). This adhesive is also used around the connecting parts to prevent air leaks, i.e., around base of the cap and the body, and at the ends of the core. A single Kevlar fiber of 0.38-mm diameter is wound along the groves made from the mold in a clock-wise and counter clock-wise directions, and a thin layer of silicone is applied on the threading to anchor it in place and prevent it from moving during actuation and grasping. A second layer 2-mm thick is made with the same casting techniques, but with a shore hardness 20 A silicone rubber (Dragon Skin 20, Smooth-on Inc., PA, USA), and used as a sleeve over the first layer.

The first layer of the device is made with very flexible rubber to ensure the lower limit of the device’s stiffness is kept at a minimum while it is directly exposed to pressure. However, the high compliance of the first layer compromises its structural integrity. Therefore, a secondary layer of the same compliance is made as a sleeve over the first. The user may utilize a third sleeve with less compliant materials to increase the upper limit of the device’s stiffness range. The interchangeability of sleeves provides greater customization and adaptability for the user’s specific needs. In addition, the interchangeability feature allows for improved sanitary environments by allowing physicians to swap sleeves between patients quickly.

Principle of Operation

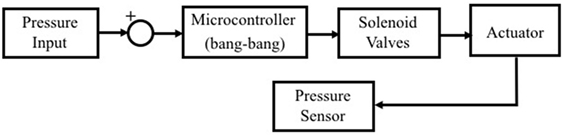

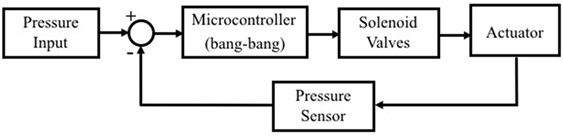

There are two modes of operation for the soft robotic haptic interface: (1) isometric and (2) constant pressure. Both of these systems utilize a bang–bang controller. The former mode is a system with no pressure regulation. Therefore, the device is given a starting pressure (greater than 0 kPa) and the internal pressure is allowed to increase with an increased force exertion on the device. This actuation system is shown on the open-loop control system block diagram in Figure 3. The latter mode of operation involves regulated pressure. Therefore, the device is given a starting pressure (greater than 0 kPa), and the internal pressure is maintained at that pressure as the hand grasping force exerted on the device is increased. This actuation system is shown on the closed-loop control system block diagram in Figure 4.

Figure 3. Open control loop scheme with a sensor to measure air pressure in the soft haptic actuator and close the solenoid valves with no further regulation.

Figure 4. Feedback control loop scheme with a microcontroller to turn solenoid valves on or off for air pressure regulation using the information measured from the pressure sensor.

Constant Pressure Control

The design for the closed-loop system is achieved by employing solenoid valves to both pressurize and depressurize the actuator based on the user’s input. The pressure input is fed through solenoid valves (Series 11 Miniature Solenoid Valves, Parker Hannifin Corp., OH, USA) before they split to equal pressures in the haptic interface and a fluidic pressure sensor (ASDXAVX100PGAA5, Honeywell International Inc., Morris Plains, NJ, USA). The pressure sensor provides feedback to a microcontroller (Arduino Uno R3, Arduino LLC., Italy) to turn the solenoid valves on and off to regulate the pressure to an approximate accuracy of 0.1 psi. When the pressure sensor reads the pressure input to be higher or lower than the desired preset input, it will depressurize or pressurize, respectively.

Isometric Control

In the open-loop mode, the pressure sensor is utilized to monitor the pressure variations inside the device. The microcontroller is set to keep the solenoid valves closed, thereby preventing a pressure drop in the system once the initial pressure has been set.

Device Characterization and Testing

Characterization

Generally, an object’s stiffness is described by the Young’s Modulus, which is the ratio of the pressure (force per unit area) applied on the object and its relative deformation. However, for small strains, as expected in this case, the compliance of the soft haptic interface can still be characterized by the ratio of the force exerted on it and the resulting displacement (Bergmann Tiest and Kappers, 2009; Bergmann Tiest, 2010):

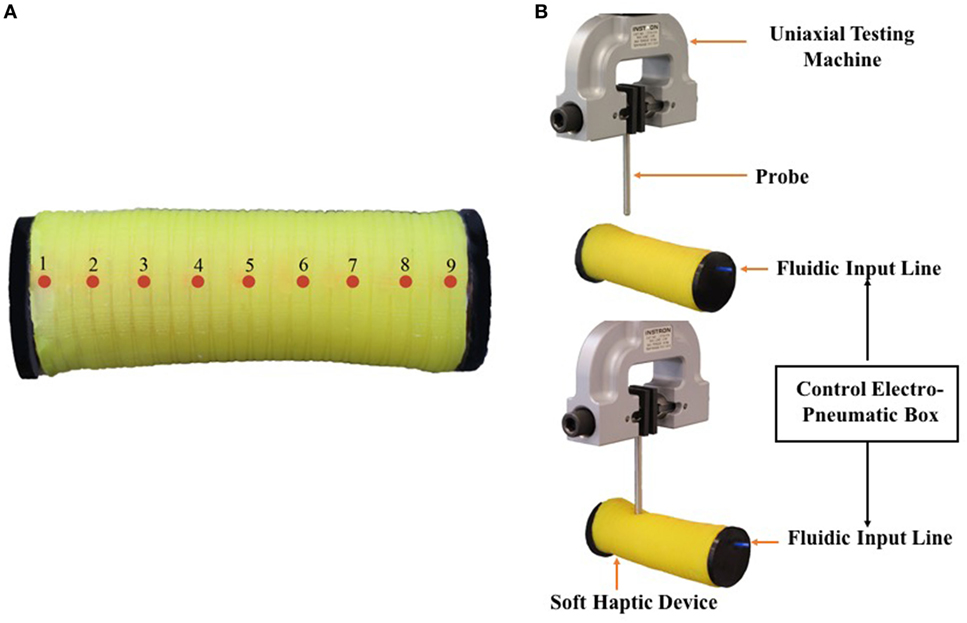

The equation describing this characterization is shown in Eq. 1, where k, Δx, and F represent stiffness, displacement, and force applied, respectively. A stiffness characterization experiment was performed to determine the stiffness profile of the grasping area of the soft robotic haptic interface. This was done by marking the device’s soft body with nine linear points with spacing of 15 mm in between in each point (Figure 5A). Point 1 is the point closest to the end cap on the side with a pneumatic tubing, and point 9 is at the furthest opposite end. These points were selected primarily due to the shape of the device. Due to its cylindrical geometry, it could be assumed that the characterization will be similar all around the device. The device is fixed in place by the core using a bar clamp with the marked points being exposed upwards. The clamp is attached to the lower grip of a uniaxial testing machine (Instron 5944, Instron Corp., High Wycombe, UK) while a probe of 6-mm diameter is attached on the upper grip (Figure 5B).

Figure 5. (A) Top view of the device with probing points identified along the length of the soft haptic interface. (B) Testing of the soft haptic device using a uniaxial testing machine (Instron 5944) before probing (top) and after probing (bottom).

The probe is positioned right above the point to be tested, and force and position of the probe are set to 0 N and 0 mm, respectively. In a quasi-static, cyclical (loading-unloading) experiment the probe is set to lower a maximum of 10 mm into the soft material body of the device while a preset pressure is provided at the beginning of the experiment. The resulting force and displacement of the probe are recorded. A total of three trials are performed per probing point, and the exerted force and displacement are averaged. The characterization experiment is repeated with preset pressurizations of 0.5, 1, 2, and 3 psi (which convert to 3.45, 6.89, 13.79, and 20.68 kPa, respectively).

Constant Pressure and Isometric Testing

These experiments were conducted to determine the efficacy of the device’s modes of operation since the effective region of variable stiffness has been determined. For the constant pressure mode of operation, a similar test to the characterization experiment is performed but the closed-loop system is utilized instead. In addition, the mid-point on the device (point 5) is selected as the only probing location to record the resulting force. This was the only point chosen since it had the most change in stiffness as identified from the characterization experiment, and it was imperative to choose a point where small changes in stiffness can be easily observed. A total of three trials are performed, and the exerted force is averaged. This is repeated with pressurizations of 0.5, 1, 2, and 3 psi.

For the isometric mode of operation, this quasi-static experiment is performed while using the open-loop system. This experiment also utilized the mid-point (point 5) on the device as the only probing location. This point was chosen since it was imperative to observe a point where the change in stiffness can easily be identified given the small testing parameters being utilized. However, the probe is set to probe four times with 2.5-mm intervals between each vertical probing distance (starting at 2.5 mm) for a given starting pressurization. The resulting pressure and the force exerted on the device were then recorded. The stiffness per displacement is then calculated using Eq. 1 and plotted against the pressure recorded for that displacement. Three trials per displacement was performed, and the exerted force and pressure were averaged. This experiment was repeated with pressurizations of 0.5, 1, 2, and 3 psi.

Efficacy of Device

To maximize the efficacy of this variable stiffness device, it is essential that the change in compliance is adequately perceived by the person using the device. This is because the essence of this technology is to have variance in stiffness that begins with very low resistance so as to differentiate itself from existing rigid variable stiffness devices. Therefore, the end user needs to be able to readily differentiate the stiffness of the device from the lowest stiffness setting up to the highest. More importantly, perception of stiffness often involves a variety of somatosensory modalities, such as mechanoreceptors, muscle spindles, and Golgi tendon (Jones and Hunter, 1990; Bergmann Tiest and Kappers, 2009), as well as the ability to coordinate joint positions and contact forces. Therefore, this type of tasks could have potential application in the rehabilitation of sensorimotor function of hands.

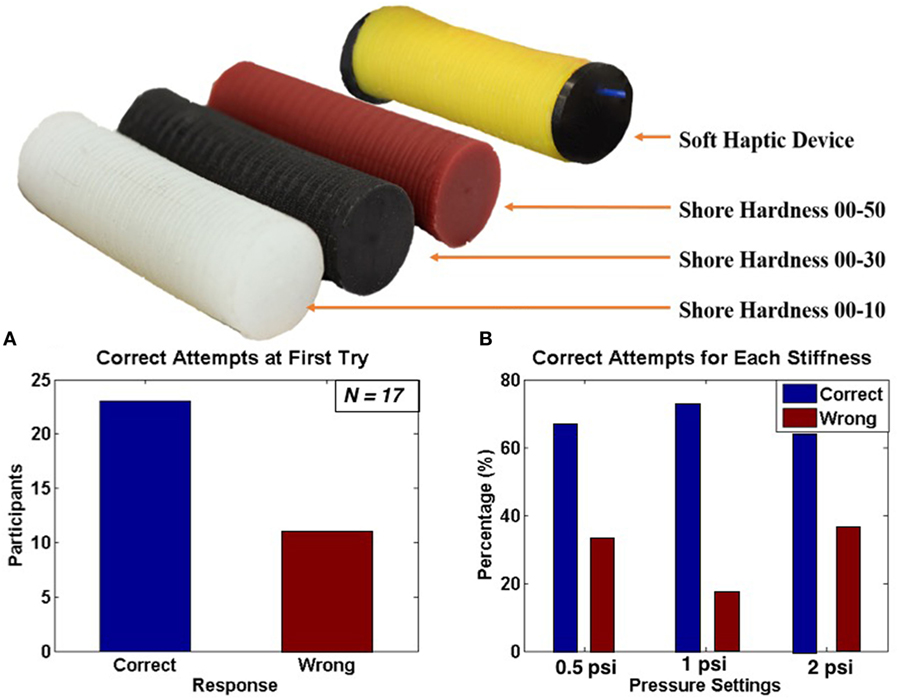

To test the stiffness perception, the soft haptic device was set at a constant pressure utilizing the open-loop control system. The stiffness per pressure setting (0.5, 1, or 3 psi) is approximated to three distinct Shore Hardness (00-10, 00-30, and 00-50, respectively). Three cylindrical objects of Shore Hardness 00-10, 00-30, and 00-50 of the same dimensions as the soft haptic device were then fabricated but with a filled center. Under an Arizona State University institutional review board approval (#1309009629), a written informed consent was obtained from healthy participants where they were asked to grasp the three filled cylindrical objects and then grasp the soft haptic device that is set at a pressure setting unknown to them. Whether the participant matched it to our set Shore Hardness correctly for the given pressurization is then recorded. This was then repeated another time with the same participant but with a different pressure setting. This qualitative experiment is repeated with the same participant but at a different pressure setting. This experiment is conducted with 17 healthy participants (totaling 34 trials) who gave their full written and oral consent before participation.

Results

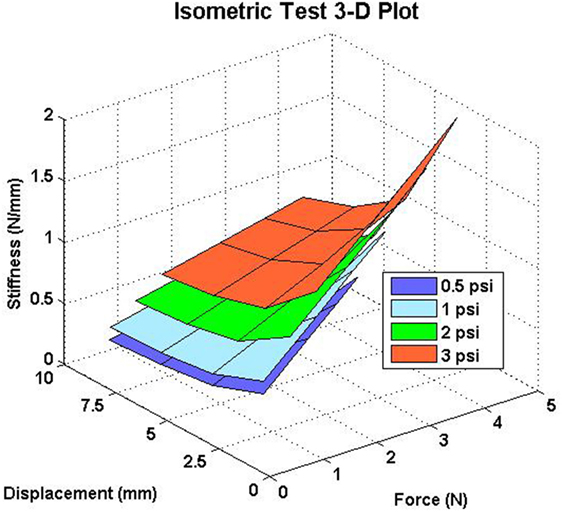

The stiffness profile versus the points on the device with varying pressures is presented in Figure 6. We expected the device to be stiffer as one moves away from the middle (point 5) of the device. This expectation was consistent with experimental results from the characterization test of the soft haptic device (Figure 6A). The device has greater stiffness at points closer to the end caps and, therefore, the regions of effective variable stiffness can be identified between points 3 and 7 where the stiffness for each pressure appear to plateau. The greater stiffness toward either ends of the device is mainly due to the influence of the bond between the end caps and the body of the actuator. For this reason, points 1 and 9 were excluded from the data. The graph of the exerted force and displacement with varying pressures using the constant pressure system is presented in Figure 6B. Using this plot, the end user has the ability to select a fixed stiffness value when using the soft haptic interface in a constant pressure mode to perform grasping exercises where the haptic feel remains the same irrespective of the grasping force exerted on the device. Conversely, the stiffness reduced for every increment in displacement in the isometric testing (Figure 7), however, the drop was consistent for every pressure input. This validates the concept of a controllable increased stiffness with varying pneumatic actuation in the soft haptic interface, which enables the device to increase its stiffness when a gradual force is exerted on it. Overall, the two modes allow for stiffness values to be adjusted on demand to higher or lower ranges through variations of the initial stiffness of the sleeves and the internal pneumatic pressure.

Figure 6. (A) The device characterization for varying pressure inputs, with the effective variance in stiffness being between points 3 and 7. (B) Force exerted on the soft haptic interface over a fixed displacement and regulated pressure for stiffness reference. The pressurizations of 0.5, 1, 2, and 3 psi convert to 3.45, 6.89, 13.79, and 20.68 kPa, respectively.

Figure 7. The variance in stiffness as the pressure in the soft-haptic interface is increased in the open-loop system. The pressurizations of 0.5, 1, 2, and 3 psi convert to 3.45, 6.89, 13.79, and 20.68 kPa, respectively.

In addition, the efficacy of the device was tested using 17 test participants to grasp the device at varying stiffness settings. Out of the 34 trials, 23 of them (or 68%) matched the stiffness of the device correctly in their first attempt as seen in Figure 8A. This number was then further broken down for the three stiffness settings and it was found that 67, 73, and 64% of the trials matched the stiffness correctly in their first attempt for the Shore 00-10, Shore 00-30, and Shore 00-50 cylinders, respectively, as shown in Figure 8B.

Figure 8. (A) Cylindrical objects of Shore Hardness of 00-10, 00-30, and 00-50 (from left to right) and the soft haptic device for participants to grasp and compare stiffness. (B) Bar plots showing the number of times participants matched the correct stiffness in their first attempt (left), and the percentage of times participants got the stiffness correct versus the percentage of times participants got the stiffness wrong (right). The pressurizations of 0.5, 1, and 3 psi convert to 3.45, 6.89, and 20.68 kPa, respectively.

Discussion

In this paper, we presented the novel design of a variable stiffness haptic interface based on soft-robotics that is pneumatically actuated to assist hand rehabilitation. The fabrication process of this device is simple and cost-effective, approximately $100, since it closely adheres to existing multistep casting and molding techniques utilized for fiber-reinforced soft actuators. The cost is used solely for research and development for this prototype. The utilization of highly compliant materials (silicone elastomers) allowed for the device to present stiffness ranges that existing variable stiffness devices are not able to achieve due to the rigidity of their mechanical designs (Masia et al., 2006; Lambercy et al., 2009; Mace et al., 2015, 2017; Malosio et al., 2016; Spagnuolo et al., 2017). Experiments were conducted to characterize the effective regions of variable stiffness in the soft haptic device due to design constraints that include regions of exponential stiffness. A closed-loop and open-loop control system were presented and tested. Finally, the variance of stiffness in the device was tested with healthy participants to ensure that the induced variance in stiffness translates adequately to a qualitative measure as well. One of the most challenging aspects of creating a device of variable stiffness is to ensure the variance in compliance is appropriately perceived by the users. This is challenging due to the multitude of factors involved in human perception of stiffness (Jones and Hunter, 1990; Bergmann Tiest, 2010). The experiment results show that healthy participants could effectively distinguish the variance in stiffness of the soft haptic device, and that the qualitative measurement could be matched to a quantitative value (Shore Hardness). This allows for a more cohesive mapping of the soft haptic device and, therefore, provides the device’s user(s) the tool necessary to utilize the device effectively. Below we describe the main findings and potential applications of our soft-robotics device for rehabilitation of sensorimotor function of hands.

Characterization

The central region (points 3–7, Figure 6A) is characterized by an increasing stiffness that could be manipulated on demand by the end user or physical therapist in a controlled fashion by increasing the pressure input to the device. It is important to note that only four different pressure settings were tested in this work as a proof-of-concept. If desired, additional pressure settings can be utilized for this particular design. However, the maximum pressure input presented was 20.68 kPa so as to prevent the device from buckling under greater internal pressure. To increase the upper limit of the pressure input, a greater number of sleeves can be added to the device, sleeves of higher stiffness can be incorporated into the design, and/or the number of windings on the first layer could be increased. This once again proves the versatility of this device to be used in stroke rehabilitation given the importance of tailoring task difficulty or characteristics to individual patients’ sensorimotor deficits.

Constant Pressure and Isometric Testing

The constant pressure test support using the device to calculate the stiffness a user can expect when using the device at a given regulated pressure. This could be eventually used to formulate a chart for quick reference if a particular setting is desired for a rehabilitative exercise to be performed. This setting can be utilized for strength training that requires a large number of hand grasping/squeezing repetitions since high repetitions have shown to increase neural plasticity in stroke recovery. The isometric mode provides the user with an option to increase the force needed to squeeze the device at a given pressure, thus being useful for users who need consistent increases in difficulty for each rehabilitative exercise. These two different modes can be utilized by the physician depending on the needs of the stroke patient. However, the results of this testing showed that the stiffness dropped for 2.5 mm increments in the displacement using the isometric system. Given that the stiffness increased during characterization which utilized the same control system, it appears that the pressure in the soft haptics is escaping when small displacements occur in the device.

Implication to Hand Rehabilitation

Our results demonstrated great potential to use the proposed device in a variety of hand-rehabilitation exercises. For instance, patients who need fixed stiffness with increased repetitions of grasping exercise could use the constant pressure control mode; and patients who need increasing difficulty could utilize the isometric control mode. Furthermore, with simple sensor added to the device, patients can use it as a controller at home to perform exercises in combination with video games to mimic augmented reality feedback that currently exist for rehabilitation devices (Khademi et al., 2012). Lastly, our device has the unique feature that the entire grasp area is compliant due to the implementation of soft robotics techniques. Unlike hand rehabilitation devices with rigid mechanisms, our design could promote the practice of natural coordination among all fingers which is important in ADL tasks.

Conclusion

In the future, we expect to fabricate this device with varying factors such as thickness and stiffness of materials, as well as investigate the effects of the number of windings and the pattern of winding on the device. This would allow for a greater effective variable stiffness region on the device. Varying the materials and fabrication methods would also allow for a more airtight device that could prevent pressure leaks, thus making the mechanical behavior of the device in the isometric mode more reliable. We also plan on incorporating force sensors into the design to accurately map the region users would interact with the device, especially the force exerted under each digit. This would also allow us to develop an equation that more accurately characterizes the stiffness of the device. In addition, the potential of the device for rehabilitation applications should be assessed by testing with patients. We can present more descriptive psychophysical data from these experiments. This would also allow for dynamic testing of the device since the current results were obtained from discrete testing methodologies.

Ethics Statement

Under an Arizona State University institutional review board (IRB) approval (#1309009629), a written informed consent was obtained from healthy participants where they were asked to grasp the three filled cylindrical objects and then grasp the soft haptic device that is set at a pressure setting unknown to them.

Author Contributions

FS, QF, MS, and PP were involved in the early planning and design of the study; designed the experiments. FS and PP further developed the concept; performed the tests. FS characterized the devices for testing. All authors analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Mr. Dattaraj Sansgiri for his exploratory contributions to some of the graphics for the figures.

Funding

This research was partially supported by a Collaborative Research Grant BCS-1455866 from the National Science Foundation (NSF) to MS. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NSF.

References

Balasubramanian, S., Klein, J., and Burdet, E. (2010). Robot-assisted rehabilitation of hand function. Curr Opin Neurol 23, 661–70. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e32833e99a4

Bergmann Tiest, W. M. (2010). Tactual perception of material properties. Vision Res. 2, 189–199. doi:10.1016/j.visres.2010.10.005

Bergmann Tiest, W. M., and Kappers, A. M. L. (2009). Cues for haptic perception of compliance. IEEE Trans. Haptics 2, 189–199. doi:10.1109/TOH.2009.16

Bishop-Moser, J., and Kota, S. (2015). Design and modeling of generalized fiber-reinforced pneumatic soft actuators. IEEE Trans. Robot. 31, 536–545. doi:10.1109/TRO.2015.2409452

Deimel, R., and Brock, O. (2013). “A compliant hand based on a novel pneumatic actuator,” in Proceedings – IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Karlsruhe, 2047–2053.

Duncan, P. W., Goldstein, L. B., Horner, R. D., Landsman, P. B., Samsa, G. P., and Matchar, D. B. (1994). Similar motor recovery of upper and lower extremities after stroke. Stroke 25, 1181–1188. doi:10.1161/01.STR.25.6.1181

Foulkes, M. A., Wolf, P. A., Price, T. R., Mohr, J. P., and Hier, D. B. (1988). The stroke data bank: design, methods, and baseline characteristics. Stroke 19, 547–554. doi:10.1161/01.STR.19.5.547

Geetha, G. N., Swathi, and Athavale, S. A. (2015). Estimation of stature from hand and foot measurements in a rare tribe of Kerala state in India. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 9, HC01–HC04. doi:10.7860/JCDR/2015/13777.6582

Genecov, A. M., Stanley, A. A., and Okamura, A. M. (2014). “Perception of a haptic jamming display: just noticeable differences in stiffness and geometry,” in IEEE Haptics Symposium, HAPTICS, Houston, TX, 333–338.

Godwin, K. M., Wasserman, J., and Ostwald, S. K. (2011). Cost associated with stroke: outpatient rehabilitative services and medication. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 18(Suppl. 1), 676–684. doi:10.1310/tsr18s01-676

Jones, L. A., and Hunter, I. W. (1990). A perceptual analysis of stiffness. Exp. Brain Res. 79, 150–156. doi:10.1007/BF00228884

Jørgensen, H. S., Nakayama, H., Raaschou, H. O., and Olsen, T. S. (1995). Recovery of walking function in stroke patients: the Copenhagen Stroke Study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 76, 27–32. doi:10.1016/S0003-9993(95)80038-7

Khademi, M., Hondori, H. M., Lopes, C. V., Dodakian, L., and Cramer, S. C. (2012). “Haptic augmented reality to monitor human arm’s stiffness in rehabilitation,” in 2012 IEEE-EMBS Conference on Biomedical Engineering and Sciences, IECBES, Langkawi, 892–895.

Kleim, J. A., and Jones, T. A. (2008). Principles of experience-dependent neural plasticity: implications for rehabilitation after brain damage. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 51, S225. doi:10.1044/1092-4388(2008/018)

Lambercy, O., Dovat, L., Yun, H., Wee, S. K., Kuah, C., Chua, K., et al. (2009). “Rehabilitation of grasping and forearm pronation/supination with the Haptic Knob,” in 2009 IEEE International Conference on Rehabilitation Robotics, ICORR, Kyoto, 22–27.

Legg, L., Drummond, A., Leonardi-Bee, J., Gladman, J. R., Corr, S., Donkervoort, M., et al. (2007). Occupational therapy for patients with problems in personal activities of daily living after stroke: systematic review of randomised trials. BMJ 335, 922. doi:10.1136/bmj.39343.466863.55

Mace, M., Rinne, P., Liardon, J.-L., Bentley, P., and Burdet, E. (2015). “Comparison of isokinetic and isometric handgrip control during a feed-forward visual tracking task,” in Proc. of the International Conference on Rehabilitation Robotics (ICORR), Singapore.

Mace, M., Rinne, P., Liardon, J.-L., Uhomoibhi, C., Bentley, P., and Burdet, E. (2017). Elasticity improves handgrip performance and user experience during visuomotor control. R. Soc. Open Sci. 4, 160961. doi:10.1098/rsos.160961

Majidi, C. (2014). Soft robotics: a perspective—current trends and prospects for the future. Soft Robot. 1, 5–11. doi:10.1089/soro.2013.0001

Malosio, M., Caimmi, M., Cottini, M. C., Crema, A., Dinon, T., Mihelj, M., et al. (2016). An affordable, adaptable, and hybrid assistive device for upper-limb neurorehabilitation. J. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. Eng. 3, 1–12. doi:10.1177/2055668316680980

Masia, L., Krebs, H. I., Cappa, P., and Hogan, N. (2006). “Whole-arm rehabilitation following stroke: hand module,” in Proceedings of the First IEEE/RAS-EMBS International Conference on Biomedical Robotics and Biomechatronics, 2006, BioRob, Pisa, 1085–1089.

Nakayama, H., Jørgensen, H. S., Raaschou, H. O., and Olsen, T. S. (1994). Recovery of upper extremity function in stroke patients: the Copenhagen Stroke Study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 75, 394–398. doi:10.1016/0003-9993(94)90161-9

Polygerinos, P., Correll, N., Morin, S. A., Mosadegh, B., Onal, C. D., Petersen, K., et al. (2017). Soft robotics: review of fluid-driven intrinsically soft devices; manufacturing, sensing, control, and applications in human-robot interaction. Adv. Eng. Mater. 1700016. doi:10.1002/adem.201700016

Polygerinos, P., Wang, Z., Galloway, K. C., Wood, R. J., and Walsh, C. J. (2015a). “Soft robotic glove for combined assistance and at-home rehabilitation,” in Robotics and Autonomous Systems, ed. B. J. Nelson (Piscataway: Elsevier B.V), Vol. 73, 135–143.

Polygerinos, P., Wang, Z., Overvelde, J. T. B., Galloway, K. C., Wood, R. J., Bertoldi, K., et al. (2015b). Modeling of soft fiber-reinforced bending actuators. IEEE Trans. Robot. 31, 778–789. doi:10.1109/TRO.2015.2428504

Popović, D. B., and Popović, M. B. (2006). “Hybrid assistive systems for rehabilitation: lessons learned from functional electrical therapy in hemiplegics,” in Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology – Proceedings, New York, NY, 2146–2149.

Seo, N. J., Armstrong, T. J., and Arbor, A. (2008). Investigation of grip force, normal force, contact area, hand size, and handle size for cylindrical handles. Hum. Factors 50, 734–744. doi:10.1518/001872008X354192

Spagnuolo, G., Malosio, M., Dinon, T., Molinari Tosatti, L., and Legnani, G. (2017). Analysis and synthesis of LinWWC-VSA, a variable stiffness actuator for linear motion. Mech. Mach. Theory 110, 85–99. doi:10.1016/j.mechmachtheory.2016.11.002

Stanley, A. A., Gwilliam, J. C., and Okamura, A. M. (2013). “Haptic jamming: a deformable geometry, variable stiffness tactile display using pneumatics and particle jamming,” in 2013 World Haptics Conference, WHC, Daejeon, 25–30.

Taylor, T. N., Davis, P. H., Torner, J. C., Holmes, J., Meyer, J. W., and Jacobson, M. F. (1996). Lifetime cost of stroke in the United States. Stroke 27, 1459–1466. doi:10.1161/01.STR.27.9.1459

Warraich, Z., and Kleim, J. A. (2010). “Neural Plasticity: The Biological Substrate for Neurorehabilitation.” PM and R 2 (12 SUPPL). Maryland Heights, MO: Elsevier Inc., S208–S219.

Wilkinson, P. R., Wolfe, C. D., Warburton, F. G., Rudd, A. G., Howard, R. S., Ross-Russell, R. W., et al. (1997). A long-term follow-up of stroke patients. Stroke 28, 507–512. doi:10.1161/01.STR.28.3.507

Winstein, C. J., Rose, D. K., Tan, S. M., Lewthwaite, R., Chui, H. C., and Azen, S. P. (2004). A randomized controlled comparison of upper-extremity rehabilitation strategies in acute stroke: a pilot study of immediate and long-term outcomes. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 85, 620–628. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2003.06.027

Keywords: soft robotics, stroke, rehabilitation, variable stiffness, haptic interface

Citation: Sebastian F, Fu Q, Santello M and Polygerinos P (2017) Soft Robotic Haptic Interface with Variable Stiffness for Rehabilitation of Neurologically Impaired Hand Function. Front. Robot. AI 4:69. doi: 10.3389/frobt.2017.00069

Received: 01 October 2017; Accepted: 04 December 2017;

Published: 20 December 2017

Edited by:

Helge Arne Wurdemann, University College London, United KingdomReviewed by:

Huichan Zhao, Harvard University, United StatesKyujin Cho, Seoul National University, South Korea

Ramon Sargeant, The University of the West Indies, Cave Hill, Barbado

Copyright: © 2017 Sebastian, Fu, Santello and Polygerinos. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Panagiotis Polygerinos, polygerinos@asu.edu

Frederick Sebastian

Frederick Sebastian Qiushi Fu

Qiushi Fu Marco Santello

Marco Santello Panagiotis Polygerinos

Panagiotis Polygerinos