Laryngeal Cryptococcosis Associated With Inhaled Corticosteroid Use: Case Reports and Literature Review

- 1Department of Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery, Monash Health, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

- 2Department of Infectious Diseases, St Vincent’s Hospital, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

- 3Department of Surgery, Faculty Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, Monash University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

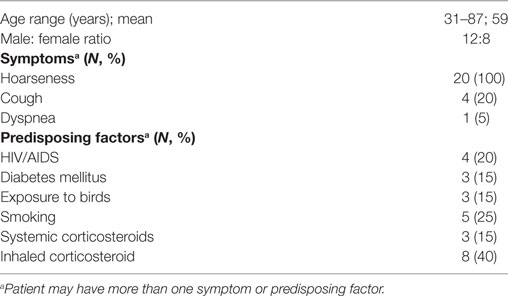

Laryngeal cryptococcosis is a rare clinical entity. There have been a limited number of case reports in the literature with no consensus regarding optimal management. This review contributes two additional case reports of immunocompetent patients with cryptococcal infection of the larynx in whom exposure to high doses of inhaled corticosteroids is proposed as a significant risk factor. Twenty cases were identified from review of the literature. All patients presented with hoarseness and a spectrum of microlaryngoscopic features, often mimicking laryngeal malignancy. The majority of cases were treated with systemic antifungal therapy, three cases had surgical excision alone, and another three had a combination of medical and surgical management. Risk factor modification, in the form of a reduction in inhaled corticosteroid was employed in the two new cases, and in some previously published cases. Risk factor modification, such as reduction of inhaled corticosteroid dose, in addition to oral antifungal agents can be effective in managing cryptococcal laryngitis.

Introduction

Cryptococcal infections in general are rare. They are most commonly seen in the setting of immunosuppression with disseminated disease or occasionally as localized disease, namely meningitis, in the immunocompetent. Laryngeal cryptococcosis is a rare condition with only 20 previous cases reported. Here, we report two further cases of cryptococcal infection localized to the larynx. Both occurred in association with high-dose inhaled corticosteroid use. Laryngeal cryptococcosis, despite its rarity, is important as it may easily be confused with laryngeal malignancy, both macroscopically and histologically. These cases provide further evidence of inhaled corticosteroid local side effects and should strengthen the clinician’s resolve to use inhaled corticosteroids at their lowest effective dose.

The Cases

Case 1

A 66-year-old female presented with a 3-month history of progressive hoarseness. She did not have any other localizing or systemic symptoms. She had a history of asthma controlled on inhaled corticosteroids for 6 years. Her other history was of congenital pulmonary stenosis and lifelong allergic rhinosinusitis. She was a non-smoker and drank alcohol rarely. She had no known exposure to Cryptococcus.

Her inhaler medication, taken twice daily, was a combination powder product containing salmeterol (50 µg) and fluticasone (500 µg) per dose. In addition, she was taking an extra 500 µg twice daily of inhaled fluticasone, followed by inhaled nedocromil, 4 mg twice daily. She did not use a spacer or nebulizer but did rinse and gargle after each inhalation. She also took intra-nasal budesonide spray at a dose of 64 µg at night. She had never been on systemic steroid treatment.

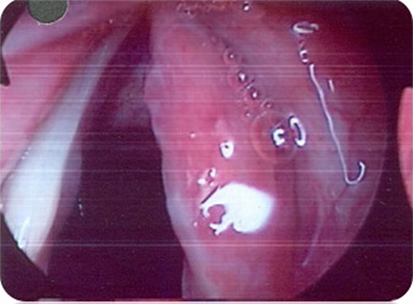

Stroboscopy revealed a markedly erythematous and thickened right true vocal fold with a marked reduction in the mucosal wave. The left true vocal fold was normal (see Figure 1).

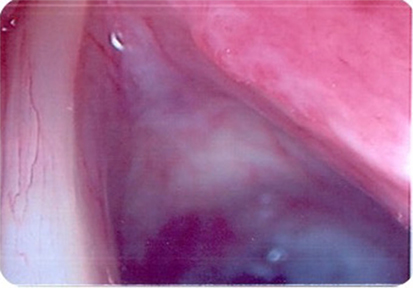

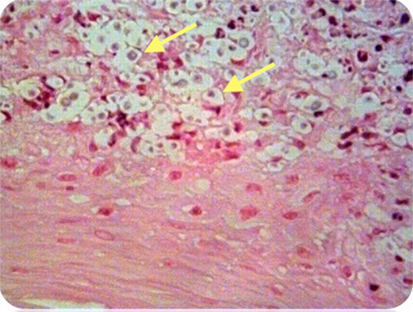

She underwent microlaryngoscopy and biopsy. Histological examination revealed collections of cryptococcal organisms lying within the superficial lamina propria, with an associated inflammatory infiltrate comprising abundant plasma cells, lymphocytes, and some histiocytes (see Figure 2). Her serum cryptococcal antigen was undetectable and her CXR unremarkable. She was HIV negative.

Figure 2. Case 1—Numerous encapsulated cryptococcal organisms (arrows) in vocal cord subepithelial stroma, H&E stain, 40×.

Treatment involved oral fluconazole, 200 mg orally, twice daily, and a reduction in her daily inhaled corticosteroid dose by half to 1,000 µg per day. Her budesonide spray was continued.

She was reviewed 7 weeks into treatment and had noted some improvement of her symptoms. At 6 months, her voice had returned to normal and repeat laryngoscopy was unremarkable. Her fluconazole was ceased after 6 months of treatment.

Case 2

A 69-year-old female presented with a 1-month history of hoarseness and post-nasal drip. Her past history included a 10-year history of moderate persistent asthma which required a short course of oral prednisolone one to two times per year. In addition, she suffered from gastro-esophageal reflux disease and recurrent urinary tract infections.

Her asthma was treated with a combination preparation containing both salmeterol (25 µg) and fluticasone (500 µg) of which she was taking two puffs, twice per day. Thus a total dose of 2,000 µg per day of fluticasone was given for 3 months prior to her presentation. She always rinsed and gargled post inhaler, but did not use a spacer. It had been more than 7 months since her last course of oral prednisolone. She also used salbutamol nebules as required. Her only non-asthma medication was omeprazole at a dose of 20 mg twice daily.

She did not have any other systemic or localizing symptoms and had no other immunosuppressive medications or conditions. She was a non-smoker and had no known cryptococcal exposure.

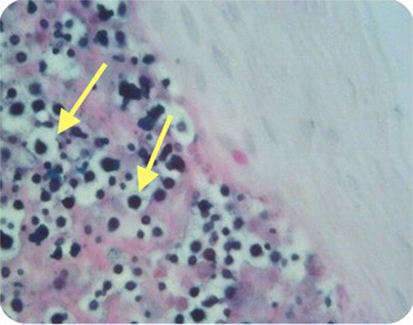

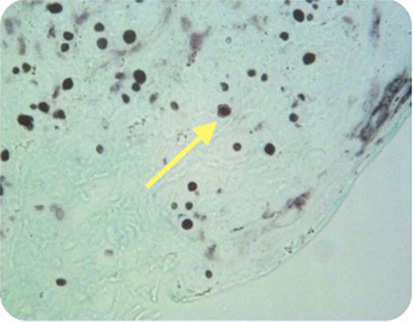

At microlaryngoscopy her right true cord was found to be inflamed, with focal erythroleukoplakia (see Figure 3). Bronchoscopy and oesophagoscopy were normal. Histopathological examination of the biopsies of the involved fold revealed focal ulceration, underlying granulation tissue, and heavy lymphocyte and plasma cell infiltration. Aggregates of Cryptococcus organisms, as confirmed by periodic acid-Schiff and methanamine silver staining, lay in the surface inflammatory crust and within the subepithelial stroma (see Figures 4 and 5). There was no hyperplasia, cellular atypia, or signs of malignancy. Her cryptococcal serum antigen recorded a very low positive of 2 via the latex agglutination test. Her fasting glucose was unremarkable at 5 mmol/l. Her CXR was within normal limits, and her HIV test was negative.

Figure 4. Case 2—Numerous encapsulated cryptococcal organisms in true cord subepithelial stroma (arrows), periodic acid-Schiff stain positive, 40×.

Figure 5. Case 2—Encapsulated cryptococcal organisms (arrow), methanamine silver stain positive, 40×.

Treatment involved oral antifungals and a reduction in her inhaled corticosteroid. She was instructed to reduce her inhaled fluticasone back to a daily maximum dose of 1,000 µg per day, and was placed on fluconazole at 200 mg twice a day.

She noticed improvement in her voice within weeks and after 5 months of fluconazole treatment her voice had returned to baseline. Stroboscopy 4 months into treatment revealed a near normal right true vocal fold with only slightly prominent vasculature, and near normal mucosal wave.

Her fluconazole was ceased after 8 months of treatment. Her voice remains normal off fluconazole, and at the lower dose of fluticasone.

Discussion

Cryptococcus neoformans is an encapsulated yeast that lives as a saprobe in nature. While other types of Cryptococcus exist, it is only C. neoformans that is considered pathologically significant. It tends to be found in association with certain trees such as eucalypts and rotting wood. It is also consistently isolated from soil contaminated by guano from birds, especially pigeons, chickens, and turkeys. The route of infections remains somewhat unclear, but aerosolised particles that infect and disseminate after alveolar deposition in the lungs is thought to be the most likely portal of entry (1). At diagnosis, however, most cases do not have a defined epidemiological exposure or chest X-ray changes (1).

Given Cryptococcus’ relative ubiquity as an organism and rarity as a disease, it is thought that host factors, play an important role in the development of symptomatic disease. Between 15 and 30% of HIV/AIDS patients in sub-Saharan Africa will contract cryptococcal meningitis during the course of their illness (2). Other predisposing conditions for systemic disease include organ transplantation, lymphoproliferative disorders, hematological malignancy, systemic corticosteroid treatment, cirrhosis, and sarcoidosis (even without steroid treatment). An association with diabetes is not definitely known. A deficiency in cellular immunity seems to be the most important risk factor for cryptococcal disease (1). That said, one-third of patients lack any obvious immune deficit (1).

In immunosuppressed patients the pattern of disease tends to be disseminated with multiple sites being involved at the time of diagnosis, most commonly the lung and meninges, though the disease can involve practically any site. Similarly, mycotic infections of the larynx tend to arise, in immunocompromised hosts and also tend to occur as a result of dissemination of the organism, or at least contiguous spread, as is the case with laryngeal candidiasis, which usually coexists with oral candidiasis (3). That said, there are increasing reports of mycotic laryngitis with a normal immune status (Candida, aspergillosis, coccidiomycosis, histoplasmosis) (4).

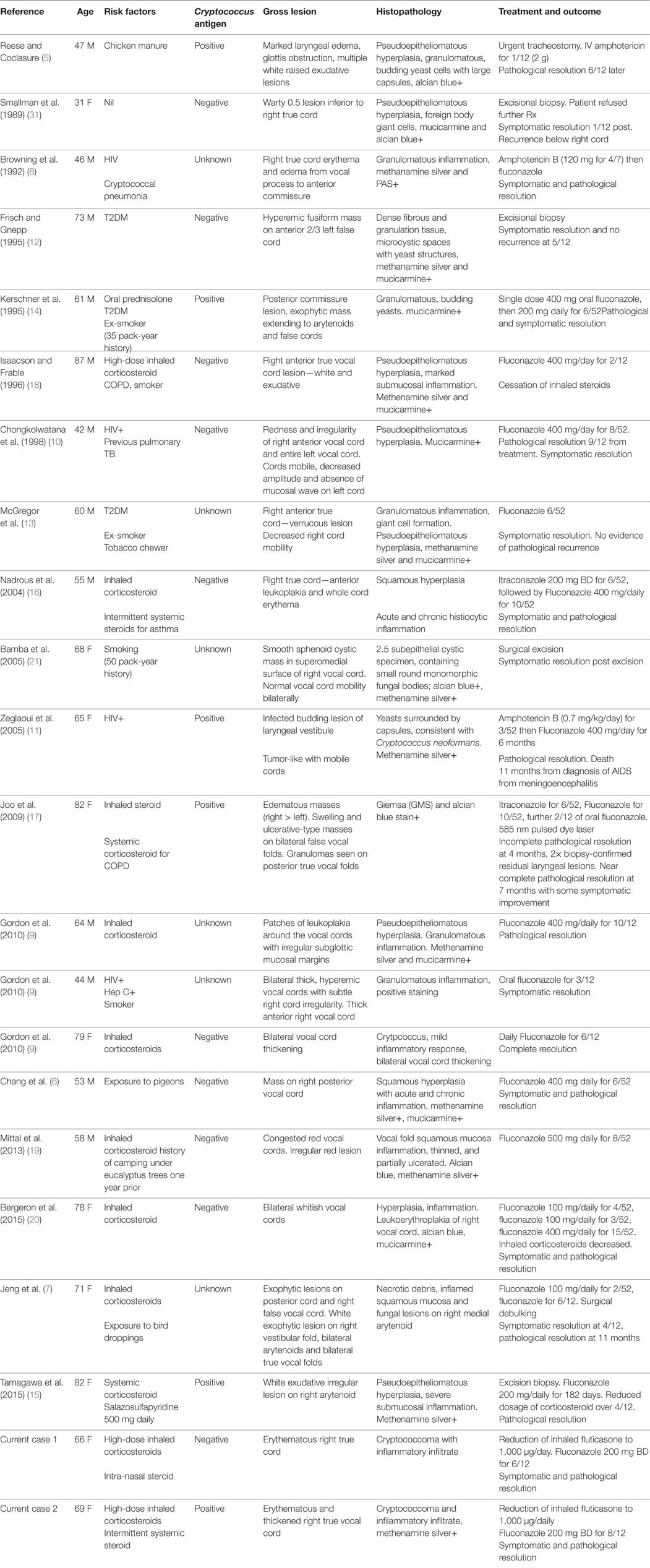

The previously reported and current cases of laryngeal cryptococcosis are summarized in Table 1 with baseline characteristics listed in Table 2.

Of the previously reported cases, only three had possible cryptococcal exposure. One patient had exposure to chicken manure (5), another had exposure to pigeons (6) and bird droppings prior to presentation (7). Several patients had a history of immunosuppresion: four with significant systemic immunosuppression in the form of HIV/AIDS (8–11); three patients with diabetes mellitus (12–14); and one patient was steroid-dependent and on immunosuppressant medication for rheumatoid arthritis (15). Importantly, 8 of the 20 cases (i.e., 40%), were using inhaled corticosteroids (7, 9, 16–20). Two of these patients were also on systemic steroids as a confounder for obstructive airways disease (16, 17). Our cases describe a further two immunocompetent patients with isolated laryngeal cryptococcosis who were exposed to inhaled corticosteroids. These cases further suggest that inhaled corticosteroids, particularly in high doses, are a potential risk factor for developing isolated laryngeal cryptococcosis in immunocompetent patients.

In immunocompetent patients with isolated laryngeal disease, the role of localized immunosuppression and disruption of the laryngeal mucosal barrier is important. Factors described as causing such a disruption include previous radiotherapy, gastro-esophageal reflux, traumatic intubation, smoking, and inhaled corticosteroids (3). Five of the reported patients had a history of smoking (9, 13, 14, 18, 21). Previous case reports have emphasized local immunosuppression from inhaled high-dose corticosteroids as a risk factor for laryngeal cryptococcal disease (9, 18–20). Our cases have similarities to those reported elsewhere in the literature with the exception of a stronger link to the use of high-dose inhaled corticosteroids.

Inhaled corticosteroid likely creates a localized immunosuppression within the larynx which along with its observed local irritation effect (22) causes an impairment of the epithelial barrier and allows the ubiquitous Cryptococcus to colonize and infect via direct inoculation. Studies suggest that up to 90% of inhaled drug is deposited in the upper airway of patients using inhalant devices, and it is this deposition that accounts for the local side effects of inhaled corticosteroids (23). Interestingly, descriptions of similar mycotic infections of the lungs, in immunocompetent patients are rare.

All of the reported patients using high-dose inhaled corticosteroids, including our two cases, presented with sub-acute onset dysphonia and a dry cough. Dysphonia is reported in up to 50% of patients using inhaled corticosteroids. The pathogenesis of steroid inhaler-related dysphonia is variable, but commonly caused by local irritation in the larynx from deposited inhalant. This irritation is seen across drug and propellant types (22), though dose and frequency seem to have an impact (22, 24). Laryngeal candidiasis can cause dysphonia or present as altered taste and is seen in around 5–10% of inhaled corticosteroid users (22, 25, 26). Adductor palsies of the vocal cords are another cause of dysphonia and thought to develop due to localized myopathy due to laryngeal corticosteroid deposition (22, 25, 26). Fluticasone is implicated as the most common cause of local steroid side effects such as dysphonia and oral candidiasis. Although this may merely reflect its widespread use (22, 24, 27–29), it is the most potent of the inhaled corticosteroids with the greatest receptor affinity and longest half-life (24, 27, 30). One study reported more than double the rate of oral candidiasis in those taking fluticasone compared with beclomethasone (29).

The differential diagnosis for the macroscopic appearance of the laryngeal cryptococcosis includes other fungal infections and malignancy. This is especially true in patients presenting with painless progressive dysphonia. This differential is echoed histologically where the typical pathological appearance of pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of the squamous mucosa, and granulomatous inflammation in the submucosal region is seen in a number of conditions, including other mycotic infections (due to Candida, Histoplasma, Blastomyces, Coccidioides, or Paracoccidiodes species) (3), granular cell tumor, and early squamous cell carcinoma. This is further complicated by the fact that there is often a low yield of yeast cells in the biopsy, and these may be missed if not specifically looked for. This problem is compounded by the rarity of laryngeal cryptococcosis as practitioners may fail to consider the condition.

Treatment was varied among the published cases. Most cases in the literature were medically managed with oral antifungal agents; however, three cases had surgical excisions (12) and three had a combination of both (7, 15, 17). Fifteen cases received a minimum of 6–8 weeks of oral fluconazole treatment. One patient refused treatment following initial surgical excisional biopsy (31). One patient received a month of intravenous amphotericin (2 g total) (5). One HIV/AIDS patient received 4 days of intravenous amphotericin followed by maintenance fluconazole (8). Another with HIV had amphotericin for 3 weeks then oral fluconazole for another 6 months (11). Interestingly, two immunocompetent patients achieved cure with excisional biopsy alone (12, 21). Of the non-HIV patients who were treated, all remained disease free on prolonged follow-up. Most had taken weeks to months for their voices to normalize.

Importantly, we believe risk factor modification (by means of dose reduction in inhaled corticosteroid) is a useful adjunct to medical management, especially in patients taking high doses. On diagnosis, patients should be commenced on antifungal treatment without delay.

Review of the literature has shown that while 8 of the 20 published cases described inhaled corticosteroid as a potential risk factor, only two cases included some description of the dose (16, 18). Of these eight cases, only two described reduction or cessation of inhaled steroid as part of their management. Certainly, the remainder of the cases that did not describe any dose reduction still had symptomatic or pathological resolution after appropriate treatment. However, the lack of dose description makes it difficult to infer that the inhaled steroids were causing local laryngeal immunosuppression in all cases.

At present, there is uncertainty surrounding the evidence for dose-reduction alone in the setting of high-dose inhaled steroids in immunocompetent hosts with cryptococcal laryngitis. The decision for dose reduction should be made on a case-by-case basis, based on the severity of the patient’s pulmonary status. A change to ciclesonide, a relatively new inhaled corticosteroid could also be of potential benefit in treating laryngeal cryptococcosis. It is an inactive pro-drug, with a smaller particle size, which is converted to an active metabolite in the airways, with potentially fewer upper airway adverse effects. A recent systematic review comparing ciclesonide to other inhaled corticosteroids in the treatment of asthma in children, however, found no difference in adverse effects (25). Both our cases were inhaling doses exceeding the maximum recommended dose. Dose reduction in addition to oral fluconazole led to successful resolution.

Conclusion

Laryngeal cryptococcosis, despite its rarity, is an important condition to diagnose, and as these two additional cases demonstrate, can occur in immunocompetent patients with possible local immunosuppression due to high dose inhaled corticosteroids. With correct diagnosis, risk factor modification (including inhaled steroid reduction), and oral antifungal treatment, it is a curable condition. It is especially important to be aware of the condition as a differential to early malignancy and other causes of inhaled steroid-related dysphonia.

Author Contributions

All Authors were involved in the write-up of the manuscript, review, and editing. Dr Stanley contributed the clinical details of the two cases for discussion.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that they have no financial or other conflicts of interest in relation to this research and its publication.

References

1. Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R. Chapter 261: cryptococcus neoformans. In: Perfect JR, editor. Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 6th ed. Elsevier Health Sciences (2005).

2. Cox GM, Perfect JR. In: Rose BD, editor. Microbiology and Epidemiology of Cryptococcal Infection. Waltham, MA: UpToDate (2007).

3. Mehanna HM, Kuo T, Chaplin J, Taylor G, Morton RP. Fungal laryngitis in immunocompetent patients. J Laryngol Otol (2004) 118(5):379–81. doi:10.1258/002221504323086615

4. Ravikumar A, Prasanna Kumar S, Somu L, Sudhir B. Fungal laryngitis in immunocompetent patients. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg (2014) 66(Suppl 1):375–8. doi:10.1007/s12070-011-0322-7

5. Reese MC, Colclasure JB. Cryptococcosis of the larynx. Arch Otolaryngol (1975) 101(11):698–701. doi:10.1001/archotol.1975.00780400056016

6. Chang YL, Hung SH, Liu CH, Hsu HT, Chao PZ, Lee FP, et al. Cryptococcal infection of the vocal folds. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health (2013) 44(6):1043–6. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofv160

7. Jeng JY, Tomblinson CM, Ocal IT, Vikram HR, Lott DG. Laryngeal cryptococcosis: literature review and guidelines for laser ablation of fungal lesions. Laryngoscope (2015) 126(7):1625–9. doi:10.1002/lary.25749

8. Browning D, Schwartz D, Jurado R. Cryptococcosis of the larynx in a patient with AIDS: an unusual cause of fungal laryngitis. South Med J (1992) 85:762–4. doi:10.1097/00007611-199207000-00023

9. Gordon DH, Stow NW, Yapa HM, Bova R, Marriott D. Laryngeal cryptococcosis: clinical presentation and treatment of a rare cause of hoarseness. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg (2010) 142(3 Suppl 1):S7–9. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2009.08.030

10. Chongkolwatana C, Suwanagool P, Suwanagool S, Thongyai K, Chongvisal S, Metheetrirut C. Primary cryptococcal infection of the larynx in a patient with AIDS: a case report. J Med Assoc Thai (1998) 81(6):462–7.

11. Zeglaoui I, Belcadhi M, Mani R, Sriha B, Bouzouita K. [Laryngeal cryptococcosis revealing AIDS: a case report]. Rev Laryngol Otol Rhinol (Bord) (2009) 130(4–5):307–11.

12. Frisch M, Gnepp DR. Primary cryptococcal infection of the larynx: report of a case. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg (1995) 113(4):477–80. doi:10.1016/S0194-5998(95)70089-7

13. McGregor DK, Citron D, Shahab I. Cryptococcal infection of the larynx simulating laryngeal carcinoma. South Med J (2003) 1:74. doi:10.1097/01.SMJ.0000047976.06958.D6

14. Kerschner JE, Ridley MB, Greene JN. Laryngeal Cryptococcus. Treatment with oral fluconazole. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg (1995) 121(10):1193–5. doi:10.1001/archotol.1995.01890100097017

15. Tamagawa S, Hotomi M, Yuasa J, Tuchihashi S, Yamauchi K, Togawa A, et al. Primary laryngeal cryptococcosis resembling laryngeal carcinoma. Auris Nasus Larynx (2015) 42(4):337–40. doi:10.1016/j.anl.2015.01.003

16. Nadrous HF, Ryu JH, Lewis JE, Sabri AN. Cryptococcal laryngitis: case report and review of the literature. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol (2004) 113(2):121–3. doi:10.1177/000348940411300207

17. Joo D, Bhuta SM, Chhetri DK. Primary cryptococcal infection of the larynx in a patient with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a case report. Laryngoscope (2009) 119(S1):S169–169. doi:10.1002/lary.20447

18. Isaacson JE, Smith-Frable MA. Cryptococcosis of the larynx. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg (1996) 114(1):106–9. doi:10.1016/S0194-5998(96)70293-0

19. Mittal N, Collignon P, Pham T, Robbie M. Cryptococcal infection of the larynx: case report. J Laryngol Otol (2013) 127(Suppl 2):S54–6. doi:10.1017/S0022215113000522

20. Bergeron M, Gagné AA, Côté M, Chênevert J, Dubé R, Pelletier R. Primary larynx Cryptococcus neoformans infection: a distinctive clinical entity. Open Forum Infect Dis (2015) 2(4):ofv160. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofv160

21. Bamba H, Tatemoto K, Inoue M, Uno T, Hisa Y. A case of vocal cord cyst with cryptococcal infection. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg (2005) 133:150–2. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2005.01.003

22. DelGaudio JM. Steroid inhaler laryngitis: dysphonia caused by inhaled fluticasone therapy. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg (2002) 128(6):677–81. doi:10.1001/archotol.128.6.677

24. O’Byrne PM, Pedersen S. Measuring efficacy and safety of different inhaled corticosteroid preparations. J Allergy ClinImmunol (1998) 102(6):879–86. doi:10.1016/S0091-6749(98)70322-7

25. Babu S, Samuel P. The effect of inhaled steroids on the upper respiratory tract. J Laryngol Otol (1988) 102(07):592–4. doi:10.1017/S0022215100105808

26. Kuritzky L. Inhaled corticoteroids: 1. Local toxicity. Hosp Pract (2000) 35:37–8, 41. doi:10.1080/21548331.2000.11444006

27. Lipworth B. Systemic adverse effects of inhaled corticosteroid therapy. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med (1999) 159:941–55. doi:10.1001/archinte.159.9.941

28. Fairfax AJ, David V, Douce G. Laryngeal aspergillosis following high dose inhaled fluticasone therapy for asthma. Thorax (1999) 54(9):860–1. doi:10.1136/thx.54.9.860

29. Fukushima C, Matsuse H, Tomari S, Obase Y, Miyazaki Y, Shimoda T, et al. Oral candidiasis associated with inhaled corticosteroid use: comparison of fluticasone and beclomethasone. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol (2003) 90:646–51. doi:10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61870-4

30. Spahn J. In: Rose BD, editor. Mechanism of Action and Pharmacology of Glucocorticoid Therapy in Asthma. Waltham, MA: UpToDate (2007).

Keywords: Cryptococcus, larynx, laryngitis, infection, fluconazole, antifungal

Citation: Wong DJY, Stanley P and Paddle P (2017) Laryngeal Cryptococcosis Associated With Inhaled Corticosteroid Use: Case Reports and Literature Review. Front. Surg. 4:63. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2017.00063

Received: 17 September 2017; Accepted: 23 October 2017;

Published: 13 November 2017

Edited by:

Ferdinand Köckerling, Vivantes Klinikum, GermanyReviewed by:

Rajagopalan Raman, University of Malaya, MalaysiaNikolaus Ernst Wolter, Hospital for Sick Children, Canada

Copyright: © 2017 Wong, Stanley and Paddle. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Daniel Jun Yi Wong, Danield.wong@svhm.org.au

Daniel Jun Yi Wong

Daniel Jun Yi Wong Peter Stanley2

Peter Stanley2  Paul Paddle

Paul Paddle