Cognitive reflection vs. calculation in decision making

- 1Department of Psychology, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON, Canada

- 2Department of Psychology, Royal Holloway, University of London, London, UK

- 3ARC Centre of Excellence in Cognition and its Disorders, Macquarie University, Sydney, NSW, Australia

A commentary on

Cognitive reflection vs. calculation in decision making

by Sinayev, A., and Peters, E. (2015). Front. Psychol. 6:532. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00532

Sinayev and Peters (2015; hereafter S&P) present two competing hypotheses to explain performance on the Cognitive Reflection Test (CRT). They dub the first the “Cognitive Reflection Hypothesis” and attribute it to other researchers: “Each of these researchers assumes that differences in CRT performance indicated differences in the ability to detect and correct incorrect intuitions…” and “… implicitly assume that numerical ability is an irrelevant detail when it comes to solving CRT and related problems” (p. 2). They contrast this with their “Numeracy Hypothesis” which states that “the CRT is primarily a measure of numeric ability” (p. 3). S&P report two studies whose results, they argue, favor the Numeracy Hypothesis over the Cognitive Reflection Hypothesis. They conclude that numeric ability is “the key mechanism” that explains the association between CRT performance and decision making (p. 1), although they also state that the ability to detect and correction intuitions (apart from numeracy) plays a role in CRT performance. Both of the hypotheses presented by S&P emphasize the role of cognitive ability in CRT performance. In this commentary we introduce an alternative hypothesis that was not discussed by S&P; namely, that the propensity or disposition to think analytically plays an important role in CRT performance (Pennycook et al., 2015b). We discuss recent empirical evidence that supports the claim that the CRT is more than just a measure of numeracy or, more generally, cognitive ability.

Distinguishing Cognitive Ability and Analytic Cognitive Style

Dual process theorists often distinguish between disposition and ability as factors that determine good reasoning (e.g., Stanovich and West, 2000; Stanovich, 2009; Evans and Stanovich, 2013). The logic is as follows: If someone does not have the disposition or willingness to think analytically, they will not fully exercise their cognitive ability and will not do as well on the problem. Naturally, the converse is also true: If someone does not have sufficient cognitive ability, it will not matter how much time and effort they are willing to spend thinking about the problem.

This distinction has been applied to CRT performance. For example, according to Toplak et al. (2014): “the CRT is a measure of the tendency toward the class of reasoning error that derives from miserly processing. This may be why the predictive power of the CRT is in part separable from cognitive ability. The latter measures computational power that is available to the individual, but not necessarily the depth of processing that is typically used in most situations” (p. 165). That each question in the CRT cues a compelling intuitive response means that responding correctly requires that individuals expend cognitive effort despite having what initially appears to be a suitable response (Pennycook et al., 2015b). Importantly, this focus on thinking disposition does not imply that cognitive abilities (such as numeracy) are irrelevant for CRT performance. Rather, the claim is that the CRT indexes, to some degree, a disposition or propensity to think analytically (i.e., “analytic cognitive style”) in addition to cognitive ability. Prima facie evidence for the importance of thinking disposition in solving the CRT comes from the finding that few people provide the correct responses (e.g., 30.3% for the bat and ball problem among undergraduate students; Pennycook et al., 2015b) despite the apparent simplicity of the math required to check the accuracy of the intuitive response (e.g., for the bat and ball problem: 0.10+1.10 = 1.20 ≠ 1.10).

Is the CRT Just Another Numeracy Test?

If the CRT captures some aspect of analytic cognitive style, it should be predictive of a wide range of judgments and decisions. However, if the CRT is “primarily a measure of numeric ability” (S&P, p. 3), then it should only robustly predict judgments and decisions that require some sort of mathematical operation.

There is emerging evidence that analytic cognitive style—and the CRT in particular—is predictive of diverse psychological outcomes that are not traditionally associated with research in decision making (Pennycook et al., 2015c). For instance, higher scores on the CRT are associated with religious disbelief (Gervais and Norenzayan, 2012; Pennycook et al., 2012; Shenhav et al., 2012), paranormal disbelief (Pennycook et al., 2012; Cheyne and Pennycook, 2013), less traditional moral values (Pennycook et al., 2014; Royzman et al., 2014), improved scientific understanding and reasoning (Shtulman and McCallum, 2014; Drummond and Fischhoff, 2015), belief in evolution (Gervais, 2015), creativity on complex tasks (Barr et al., 2015a), less reliance on Smartphone technology as an external information source (Barr et al., 2015b), and lowered receptivity to pseudo-profound bullshit (Pennycook et al., 2015a). Indexes of cognitive ability were included as controls in many of these studies (Pennycook et al., 2015c), including, in some cases, established numeracy tests (Pennycook et al., 2014, 2015a; Barr et al., 2015a,b; Trippas et al., 2015). With few exceptions, analytic cognitive style measures (including the CRT) were predictive after controlling for cognitive ability (including numeracy; Pennycook et al., 2015c).

What, then, of the two new studies presented by S&P? That CRT performance was not predictive over-and-above numeracy may simply provide evidence that the aspect of CRT performance that reflects thinking disposition does not play a role in the types of decisions that S&P investigated. This seems particularly likely with respect to the incentivized outcomes in Study 2 (as discussed by S&P, p. 12) because the very goal of incentivizing tasks in behavioral research is to minimize dispositional variance. We suggest that a stronger test of the role of thinking disposition over-and-above numeracy would be in judgments or decisions in “naturalistic” contexts where there is no clear prompt or direct incentive to think analytically (Stanovich et al., 2013). S&P did measure some real-world outcomes (e.g., saving money for retirement). However, examined outcomes all included direct incentives (e.g., monetary reward). The evidence highlighted above indicates that CRT performance is predictive for beliefs or judgments that not only lack incentives, but lack normatively correct or incorrect outcomes.

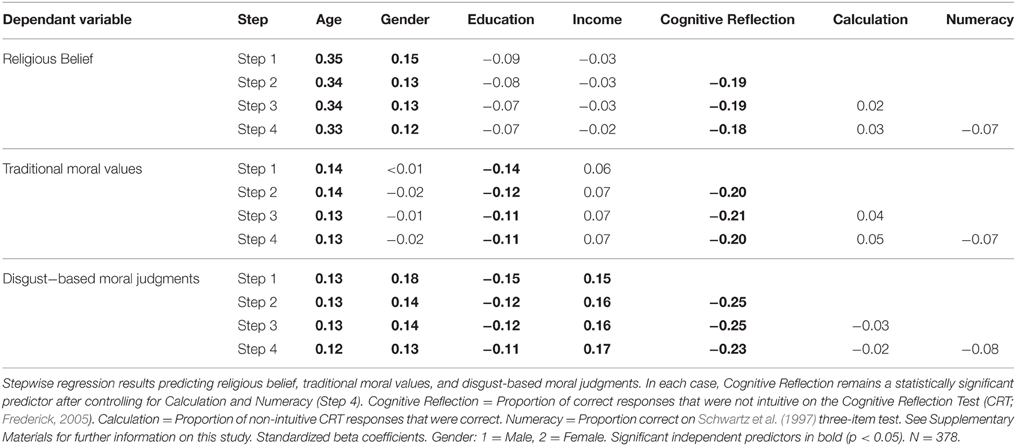

As a case study, consider the results of Pennycook et al. (2014) presented in Table 1. This study focused on predicting religious belief, traditional moral values (e.g., trust in authority, concerns over bodily purity), and disgust-based moral dilemmas. Importantly, none of these constructs has any theoretical association with numeracy, but they do involve compelling intuitions or societal defaults that could be influenced by the disposition to think analytically (for further detail, see Pennycook et al., 2014). As expected given our account, numeracy and “calculation” (using S&P's CRT scoring technique) are not significant predictors of any outcome variable, whereas “cognitive reflection” is a robust predictor for all three (see Supplementary Materials for further details about this analysis). Note, however, that it would be inappropriate to conclude on this basis that numeracy has nothing to do with CRT performance. Rather, the purpose of this analysis is to show that there are some instances where the CRT predicts an outcome even after controlling for numeracy. This indicates that the CRT is more than just a numeracy measure. Similar analyses have been done with a variety of outcome variables and with a variety of cognitive abilities as control variables (see Pennycook et al., 2015c).

Table 1. Re-analysis of Pennycook et al. (2014).

Conclusion

What is the role of analytic cognitive style and cognitive ability in decision making? Although, the answer undoubtedly depends on the sort of decision being made, we have drawn attention to evidence that the CRT is predictive of a wide range of outcomes, even after controlling for cognitive ability (Pennycook et al., 2015c). This provides evidence that CRT performance reflects, at least to some degree, a propensity or willingness to think analytically and the CRT, therefore, is not “primarily a measure of numeric ability” (S&P, p. 3).

Nevertheless, we acknowledge that a propensity to think analytically does not play an important role in all (or perhaps even most) decisions that people make in their day-to-day lives. Moreover, it is clear that the role of numeracy in CRT performance has not been adequately acknowledged by dual-process theorists. Future research could profitably follow S&P's lead by further investigating which types of decisions depend on numeracy, but not cognitive style (and vice versa). This will require indices of both analytic cognitive style and cognitive ability (and, in particular, numeracy), as well as a more nuanced hypotheses about what factors explain performance on reasoning and decision making tasks.

Author Contributions

GP wrote the initial draft of this manuscript. RR provided critical revisions.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00009/full

References

Barr, N., Pennycook, G., Stolz, J. A., and Fugelsang, J. A. (2015a). Reasoned connections: a dual-process perspective on creative thought. Think. Reason. 21, 61–75. doi: 10.1080/13546783.2014.895915

Barr, N., Pennycook, G., Stolz, J. A., and Fugelsang, J. A. (2015b). The brain in your pocket: evidence that Smartphones are used to supplant thinking. Comput. Hum. Behav. 48, 473–480. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.02.029

Cheyne, J. A., and Pennycook, G. (2013). Sleep paralysis post-episode distress: modeling potential effects of episode characteristics, general psychological distress, beliefs, and cognitive style. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 1, 135–148. doi: 10.1177/2167702612466656

Drummond, C., and Fischhoff, B. (2015). Development and validation of the scientific reasoning scale. J. Behav. Decision Making. doi: 10.1002/bdm.1906. [Epub ahead of print].

Evans, J. St. B. T., and Stanovich, K. E. (2013). Dual-process theories of higher cognition: advancing the debate. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 8, 223–241. doi: 10.1177/1745691612460685

Frederick, S. (2005). Cognitive reflection and decision making. J. Econ. Perspect. 19, 25–42. doi: 10.1257/089533005775196732

Gervais, W. M. (2015). Override the controversy: analytic thinking predicts endorsement of evolution. Cognition 142, 312–321. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2015.05.011

Gervais, W. M., and Norenzayan, A. (2012). Analytic thinking promotes religious disbelief. Science 336, 493–496. doi: 10.1126/science.1215647

Pennycook, G., Cheyne, J. A., Barr, N., Koehler, D. J., and Fugelsang, J. A. (2014). The role of analytic thinking in moral judgements and values. Think. Reason. 20, 188–214. doi: 10.1080/13546783.2013.865000

Pennycook, G., Cheyne, J. A., Barr, N., Koehler, D. J., and Fugelsang, J. A. (2015a). On the reception and detection and pseudo-profound bullshit. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 10, 549–563.

Pennycook, G., Cheyne, J. A., Koehler, D. J., and Fugelsang, J. A. (2015b). Is the Cognitive Reflection Test a measure of reflection and intuition? Behav. Res. Methods. doi: 10.3758/s13428-015-0576-1. [Epub ahead of print].

Pennycook, G., Cheyne, J. A., Seli, P., Koehler, D. J., and Fugelsang, J. A. (2012). Analytic cognitive style predicts religious and paranormal belief. Cognition 123, 335–346. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2012.03.003

Pennycook, G., Fugelsang, J. A., and Koehler, D. J. (2015c). Everyday consequences of analytic thinking. Curr. Direct. Psychol. Sci. 24, 425–432. doi: 10.1177/0963721415604610

Royzman, E. B., Landy, J. F., and Goodwin, G. P. (2014). Are good reasoners more incest-friendly? Trait cognitive reflection predicts selective moralization in a sample of American adults. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 9, 176–190.

Schwartz, L. M., Woloshin, S., Black, W. C., and Welch, H. G. (1997). The role of numeracy in understanding the benefit of screening mammography. Ann. Intern. Med. 127, 966–972. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-11-199712010-00003

Shenhav, A., Rand, D. G., and Greene, J. D. (2012). Divine intuition: cognitive style influences belief in god. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 141, 423–428. doi: 10.1037/a0025391

Shtulman, A., and McCallum, K. (2014). “Cognitive reflection predicts science understanding,” in Proceedings of the 36th Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society (Quebec City, QC), 2937–2942.

Sinayev, A., and Peters, E. (2015). Cognitive reflection vs. calculation in decision making. Front. Psychol. 6:532. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00532

Stanovich, K. E. (2009). “Is it time for a tri-process theory? Distinguishing the reflective and algorithmic mind,” in In Two Minds: Dual Processes and Beyond, eds J. St. B. T. Evans and K. Frankish (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 55–88.

Stanovich, K. E., and West, R. F. (2000). Individual differences in reasoning: implications for the rationality debate? Behav. Brain Sci. 23, 645–726. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X00003435

Stanovich, K. E., West, R. F., and Toplak, M. E. (2013). Myside bias, rational thinking, and intelligence. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 22, 259–264. doi: 10.1177/0963721413480174

Toplak, M. V., West, R. F., and Stanovich, K. E. (2014). Assessing miserly information processing: an expansion of the Cognitive Reflection Test. Think. Reason. 20, 147–168. doi: 10.1080/13546783.2013.844729

Keywords: numeracy, Cognitive Reflection Test, biases, individual differences, dual-process theory

Citation: Pennycook G and Ross RM (2016) Commentary: Cognitive reflection vs. calculation in decision making. Front. Psychol. 7:9. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00009

Received: 06 October 2015; Accepted: 05 January 2016;

Published: 22 January 2016.

Edited by:

Petko Kusev, Kingston University, UKReviewed by:

Claudia Uller, Kingston University, UKAleksandr Sinayev, The Ohio State University, USA (Ellen Peters contributed to the review of Aleksandr Sinayev)

Copyright © 2016 Pennycook and Ross. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gordon Pennycook, gpennyco@uwaterloo.ca

Gordon Pennycook

Gordon Pennycook Robert M. Ross

Robert M. Ross